Yamaguchi H. Engineering Fluid Mechanics (Fluid Mechanics and Its Applications)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

5.3 Fanno and Rayleigh Lines

0

1

2

11

0

°

¿

°

¾

½

°

¯

°

®

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

hh

k

h

c

dh

ds

v

(5.3.8)

This gives the entropy

s

maximum for

12

0

khh . Furthermore, this

12

0

khh is substituted into Eq. (5.3.2) to give

kRT

kTc

khu

p

1

1

2

(

5.3.9)

Equation (5.3.9) shows that at the maximum entropy, the flow is at the

sonic, i.e.

1

2222

aukRTuM . Similarly, we can write the gradient

of the

line from Eq. (5.3.8) in terms of the Mach number

»

¼

º

«

¬

ª

2

2

2

11

M

M

a

k

dh

ds

(5.3.10)

and as a result Eq. (5.3.10) yields the following relations for 1!k

0!

dh

ds

, 1!

M

(supersonic)

0

dh

ds

, 1

M

(sonic)

0

dh

ds

, 1

M

(subsonic)

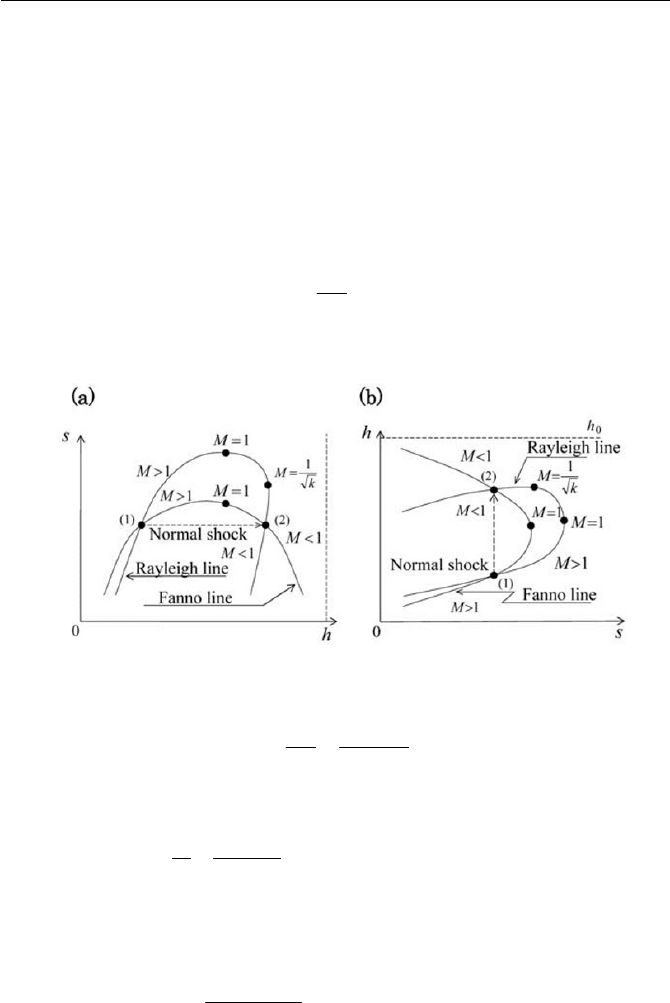

as indicated in Fig. 5.8(a) and (b). The relations characterize the Fanno line.

The equations of the Rayleigh line are also derived, on the other hand,

from the mass continuity and the momentum equation for frictionless flow,

lifting the adiabatic condition. The flow under consideration is similarly

one dimensional with steady internal flow. Instead of the energy equation,

we use the momentum equation per unit area (the momentum flux) from

Eq. (4.1.47), i.e.

Appuum

2112

2112

ppuuu

U

243

5 Compressible Flow

and by the mass continuity of Eq. (5.3.1);

12

uu

U

U

, we have the expres-

sion

.const fpuu

U

(5.3.11)

where f is called the impulse or thrust function as it is kept constant for

frictionless flow through the channel. Using the continuity of Eq. (5.3.1)

again, we may be able to modify Eq. (5.3.11) to write

p

explicitly with

the formula that follows

U

2

G

fp

(5.3.12)

For an ideal gas, the enthalpy is written by the following formula

Fig. 5.8 Fanno and Rayleigh lines

1

k

kp

R

p

cTch

pp

UU

(5.3.13)

so that

k

hk

p

1

U

(5.3.14)

Combining Eq. (5.3.12) with Eq. (5.3.14) and eliminating

U

, we can ob-

tain an expression for enthalpy as

2

2

1 Gk

pfpk

h

(5.3.15)

Nevertheless to convey the essence of the subject, it is required to write

p

in Eq. (5.3.15) in terms of the entropy in a thermodynamic system. For

244

5.3 Fanno and Rayleigh Lines

an ideal gas, the pressure

p

is a function of any two thermodynamics pa-

rameters, i.e.

shpp , . Considering Eqs. (2.5.6) with (2.5.17) by inte-

grating between the state points, we have

°

¿

°

¾

½

°

¯

°

®

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

k

v

p

p

css

U

U

2

2

2

ln

(5.3.16)

and it follows that

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

p

c

ss

k

k

e

p

p

h

h

2

1

22

(5.3.17)

where we have used,

22

TThh . Equation (5.3.17) can be further sim-

plified into

1

2

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

°

¿

°

¾

½

°

¯

°

®

k

k

c

s

p

ehCp

(5.3.18)

where

2C is a constant defined at one state point. The equation of the

Rayleigh line is now to be derived by substituting Eq. (5.3.18) into Eq.

(5.3.15) to give

0

1

2

2

2

1

2

1

2

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

°

¿

°

¾

½

°

¯

°

®

°

¿

°

¾

½

°

¯

°

®

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

h

k

k

C

a

eh

C

f

eh

k

k

c

s

k

k

c

s

pp

(5.3.19)

In Fig. 5.8(a) and (b), Rayleigh lines are displayed, having common states

with the Fanno lines. As in the case of Fanno lines, we are similarly able to

obtain the condition at

s

to be a maximum by differentiating

s

in Eq.

(5.3.19) with respect to h as

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

TkM

M

dh

ds 11

2

2

(5.3.20)

where we used the relation in Eq. (5.3.9) similar to the case of the Fanno

line. It is denoted that Eq. (5.3.20) is readily obtained by Eqs. (5.3.14)

and (10) in Exercises 5.3 together with the thermodynamics relation

245

5 Compressible Flow

Tdsdhdp

U

derived from Eq. (2.5.15). As shown in Fig. 5.8(a) and (b),

at 1

M

the entropy

s

reaches the maximum, yielding the flow character-

istics for

1

2

!kM as follows

0!

dh

ds

, 1!

M

(supersonic)

0

dh

ds

, 1

M

(sonic)

0

dh

ds

, 11 Mk (subsonic)

It is readily confirmed that at

kM 1

, the enthalpy becomes maximum

and for

11 Mk ,

dsdh

is negative, while everything other than this

region

dsdh

is positive. In Rayleigh flows, as indicated by the Rayleigh

line, the increase of entropy is due to heat given from outside the system,

since no friction is assumed. Therefore, in comparison with the Fanno flow,

which is represented by the Fanno line, self-heating of a compressible flow

has an effect to encourage the flow to reach 1

M

, and this implicitly

suggests the friction effect of the Fanno flow.

As we will see later in this chapter, a normal shock is characterized

with the mass continuity equation, the momentum equation and the energy

equation. Thus, the thermodynamic states represented at points (1) and (2)

in Fig. 5.8(a) and (b), where the Fanno and Rayleigh lines across for a

given mass flux

G

, satisfy the three equations for a normal shock. This

fact represents that through the occurrence of the normal shock the entropy

increases from points (1) to (2) of the thermodynamic states behind and

ahead of the normal shock respectively.

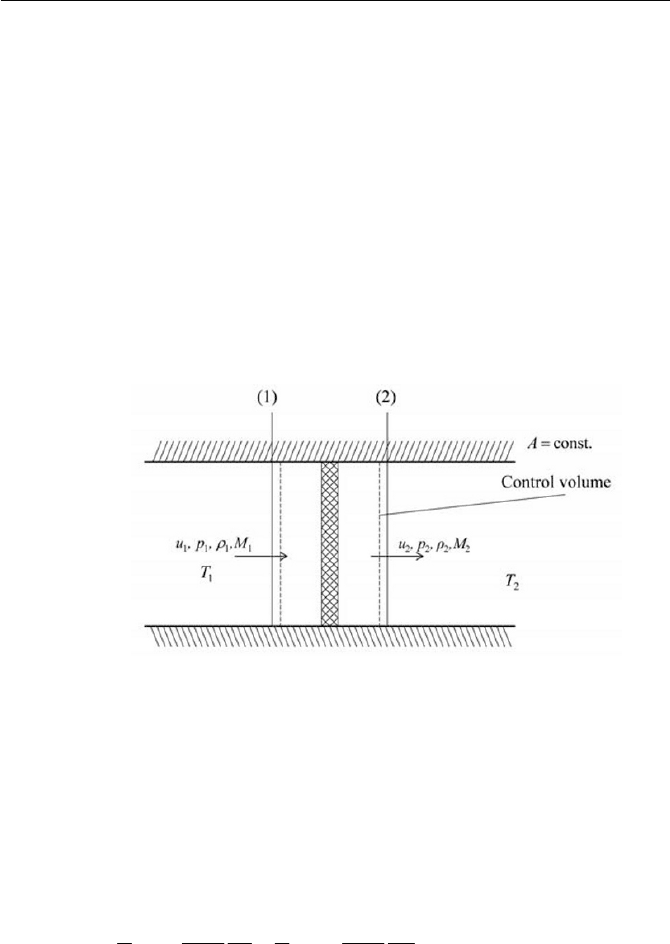

5.4 Normal Shock Waves

In a Laval tube, as studied in the previous section, when the exit pressure

is well below the reservoir pressure, there is a discontinuity in pressure as

observed in Fig. 5.5(a) and (b). The discontinuity of pressure, density and

temperature that occurs in the direction of compressible flow is a promi-

nent feature of normal shock. Also for the points where Fanno and

Rayleigh lines cross, there is an entropy increase as verified in Fig. 5.8(a)

and (b). The points (1) and (2) in Fig. 5.8(a) and (b) meet the following

conditions

246

5.4 Normal Shock Waves

(2) constant cross sectional area through the shock

(3) ideal gas

(4) steady state flow

(5) adiabatic and frictionless

It may be further stated that for the points of cross-lines, the mass con-

tinuity, the momentum and the energy equations are simultaneously satis-

fied. The normal shock, the simplest case of a shock wave, is regarded and

is observed in experiments as a surface perpendicular to the direction of

flow. Through the shock there is sudden occurrence of discontinuous

change of flow properties and the flow is irreversible, so that, although the

adiabatic condition is held, the isentropic equations cannot be used. A state

of flow for a normal shock is depicted in Fig. 5.9.

Fig. 5.9 Normal shock

The equations of mass continuity, momentum and energy are repeat-

edly written for a normal shock as

2211

uu

U

U

(5.4.1)

2

2

221

2

11

pupu

UU

(5.4.2)

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

12

1

12

1

UU

p

k

k

u

p

k

k

u

(5.4.3)

From Eqs. (5.4.1–5.4.3), we have a relationship among the flow properties

between states (1) and (2), respectively in front of and behind the normal

shock as follows

(1) one dimensional

247

5 Compressible Flow

1

2

1

2

2

1

1

2

11

11

ppkk

ppkk

u

u

U

U

(5.4.4)

With a definition of the speed of sound as Eq. (5.1.25), we can write Eq.

(5.4.4) in terms of a Mach number and its relevant forms such that

2

1

2

1

2

1

1

2

1

12

Mk

Mk

u

u

U

U

(5.4.5)

1

12

1

1

2

1

2

2

2

1

1

2

k

kkM

kM

kM

p

p

(5.4.6)

2

1

2

2

1

2

1

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

1212

1

2

1

1

1

2

1

1

Mk

MkkkM

Mk

Mk

T

T

(5.4.7)

The formula of Eq. (5.4.4) that relates to pressure and density across a

normal shock is known as the Rankine-Hugoniot relationship. This rela-

tionship stands for a normal shock wave of any strength without taking in

account of any internal structure of the wave.

The equation of a state combined with the thermodynamic expression

for entropy change is given as Eq. (5.3.16) and causes the entropy increase

as

»

¼

º

«

¬

ª

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

1

2

1

2

12

lnln

U

U

k

p

p

css

v

(5.4.8)

Substituting Eq. (5.4.4) into Eq. (5.4.8), and denoting

1

2

ppp

G

and

12

sss

G

, we can expand Eq. (5.4.8) to give

4

3

1

2

2

0

12

1

p

p

p

k

k

cs

v

G

G

G

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

(5.4.9)

Since in the normal shock wave, the entropy increases 0!s

G

, it gives a

condition that from Eq. (5.4.9), 0!p

G

. This for 0!p

G

implies that, from

Eqs. (5.4.4) to (5.4.7), the following relations must be met

248

5.4 Normal Shock Waves

2

1

u

u

,

1

2

p

p

,

1

2

T

T

,

1

2

U

U

1!

(5.4.10)

It is noted that

1

pp

G

in Eq. (5.4.9) is sometimes called the shock

strength and for 0!p

G

, the thermodynamic process is called the compres-

sion. That is to say, the normal shock wave is the compression wave and

the following conditions are to be thought:

(i) If the shock strength is small, i.e.

1

1

pp

G

, from Eq. (5.4.8) the flow

through the shock is isentropic, i.e. 0|s

G

.

(ii) Equation (5.4.4) may be written in the following form, by setting

1

2

ppp

G

and

1

2

U

U

G

U

2

1

21

UUGU

G

ppkp

(5.4.11)

and from the momentum equation of Eq. (5.4.2), we have

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

1

1

2

1

1

2

1

2

21

21

1

1

1

U

U

U

U

U

UU

p

k

p

p

ppk

u

(5.4.12)

Consequently according to Eq. (5.4.11), we can identify two conditions

for a normal shock wave: for a weak shock, i.e.

21

U

U

| and

21

pp | , Eq.

(5.4.12), which becomes

const.

2

2

1

1

1

|

UU

kpkp

u

(5.4.13)

which is the speed of sound, meaning that the shock propagates with the

speed of sound; for a very strong shock, i.e.

21

pp

and

21

U

U

, Eq.

(5.4.12) is certainly greater than the speed of sound, indicating that a very

strong shock may propagate faster than a weak shock.

When we consider the critical velocity

*

u , i.e. the velocity for the flow

reaching the speed of sound a , it will prove useful to write the energy

equation Eq. (5.4.3) as

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

12

1

12

1

12

1

*

a

k

k

p

k

k

u

p

k

k

u

UU

(5.4.14)

249

5 Compressible Flow

where

*

a is invariant between behind and ahead of a normal shock. It is

now desired to derive a useful expression for a normal shock. Eliminating

p

and

U

from Eqs. (5.4.1), (5.4.2) and (5.4.14), we can obtain a simple

expression as

2

21

*

auu

(5.4.15)

This is called as Prandtl relation. As an alternative, Eq. (5.4.15) can also be

written by

1

21

**

MM

(5.4.16)

Thus, from relationships in Eqs. (5.4.10) and (5.4.16), we have

1

1

!M

and

2

M , since

1

!

M

and

1

!

*

M

is respectively true. This indicates that a

normal wave can occur only if the upstream flow is supersonic.

It also appears, according to Eq. (5.4.16), that fo

1

M leads to

2112

uu

U

U

to reach an asymptote of

11 kk . If the value of

4.1 k

represents air, the maximum (the asymptote) is 6, meaning that air

cannot be compressed more than 6 times its original density by normal

shock, while

12

pp and

12

TT increase infinitely.

Mach number relations across a normal shock wave may be found in

the following relation

2

1

2

1

2

2

1

2

2

T

T

u

u

M

M

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

(5.4.17)

so that with the aid of Eqs. (5.4.5) and (5.4.7) we have

12

21

2

1

2

1

2

2

kkM

Mk

M

(5.4.18)

Equation (5.4.18) also indicates that for 1

1

!M and

1!k

the flow is sub-

sonic behind a normal shock wave. As for air, for example, with 4.1

k ,

Eq. (5.4.18) can be reduced to

17

5

2

1

2

1

2

2

M

M

M

(5.4.19)

1

250

5.5 Oblique Shock Wave

5.5 Oblique Shock Wave

plane of the shock wave is inclined by an angle of

E

with respect to the

incoming flow direction. This plane shock wave, termed an oblique shock

wave, is attached to the nose of the wedge, and acts to turn the flow

through a semi-vertex angle (wedge angle) of

T

so that the flow becomes

parallel to the wedge downstream from the shock. An oblique shock wave

is often observed at the nose of a supersonic aircraft.

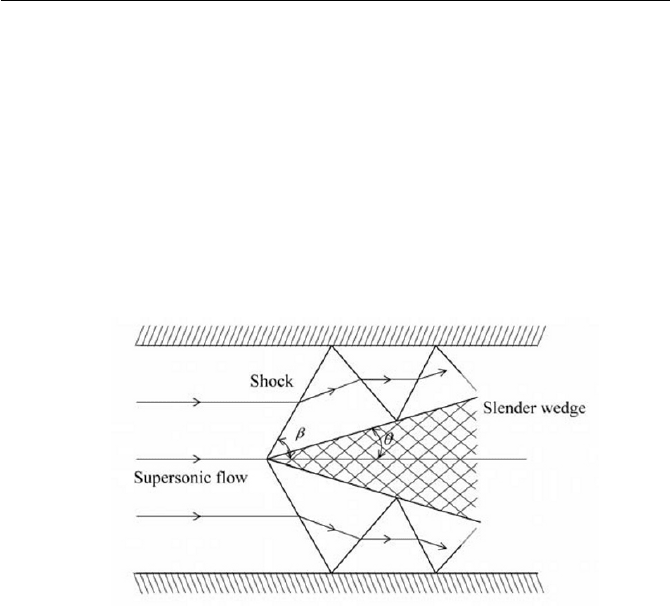

Fig. 5.10 Supersonic flow past a wedge

Figure 5.11 shows a schematic diagram of an oblique shock wave that

has been assigned kinematic properties. In dealing with an oblique shock

wave, mass continuity, momentum, and energy equations are to be solved

in the same manner as a normal shock wave. However, it should be kept in

mind that by conservation of momentum, since there is no pressure change

along the shock wave and there is no force acting on the fluid along the

shock wave plane, the tangential component of velocity

t

u is continuous

across the shock wave

222111 tntn

uuuu

U

U

(5.5.1)

Thus, with the aid of the relation

2211 nn

uu

U

U

(Eq. 5.4.1), we have

ttt

uuu

21

(5.5.2)

When a supersonic incompressible flow passes over a slender wedge, as

shown in Fig. 5.10, for example a plane shock wave is formed, when the

251

5 Compressible Flow

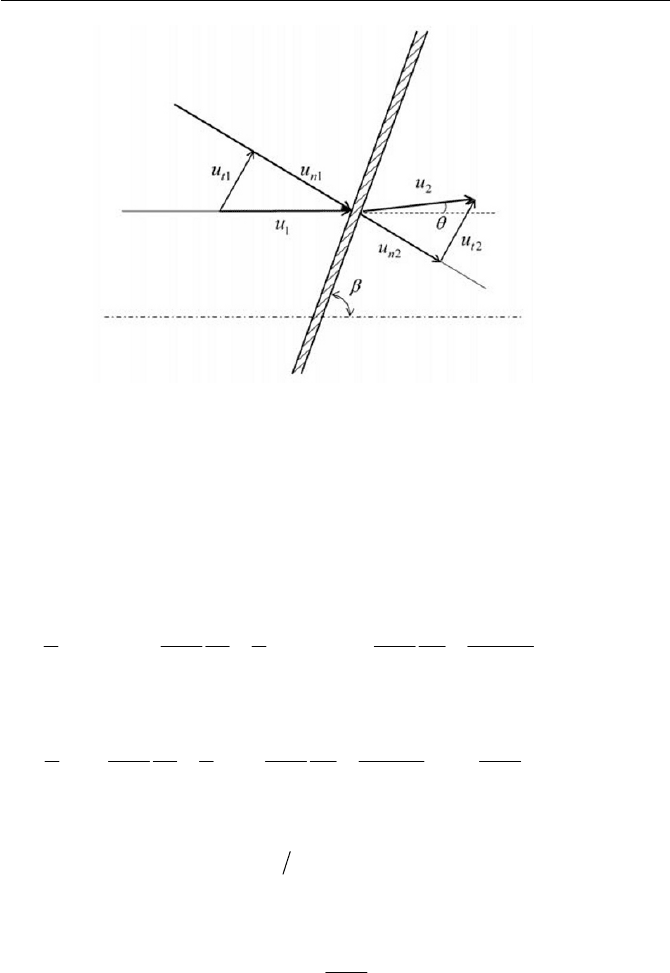

Fig. 5.11 The oblique shock

The normal components of velocity

1n

u and

2n

u are related to the normal

shock relations of the previous section. Therefore, the mass continuity,

momentum and energy equations in the normal direction to the shock are

written identically for an oblique shock when the flow properties, such as

pressure, density, temperature and etc, are related in the same way as with

the normal shock. Thus, it would be useful to write the energy equation as

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

1

12

1

12

1

*

a

kk

kp

k

k

uu

p

k

k

uu

tntn

UU

(5.5.3)

Furthermore, with the condition of Eq. (5.5.2) we have

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

22

2

2

2

2

1

1

2

1

1

1

12

1

12

1

12

1

tnn

u

k

k

a

k

kp

k

k

u

p

k

k

u

*

UU

(5.5.4)

Equation (5.5.4) is exactly the same as Eq. (5.4.14) by replacing

2

*

a from

Eq. (5.4.14) with

11

22

kuka

t

*

, so that the Rankine-Hugoniot rela-

tionship of a normal shock wave can still be valid for the oblique shock.

The Prandtl relation for the oblique shock is also written as follows

22

21

1

1

tnn

u

k

k

auu

*

(5.5.5)

With the aid of the velocity diagram in Fig. 5.11, the velocity ratios for

n

u and

t

u are expressed in terms of the shock inclination angle

E

and the

velocity deflection angle

T

as

252