Woolrych Austin. Britain in Revolution, 1625-1660

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

just ordered that the Convention should cease meeting. With the English

Convention due to meet later in the month, it clearly wanted to keep the terms

of the Restoration firmly in English hands. Annesley, who as Lord Mountjoy’s

Dublin-born son knew Ireland so well, was keeping a watchful eye on the

country, and probably persuaded the council to appoint Sir William Waller

as commander-in-chief of its army. Waller, the ‘William the Conqueror’ of

early Civil War days, was a cousin of Sir Hardress Waller, but of very

different political and religious views, for he had secretly pledged himself to

the king’s service in 1659.

By this time the complexities of Irish politics defy brief summary, but one

way and another Broghill, and to a lesser extent Coote and Annesley, deserve

credit for preserving Ireland from bloodshed and easing a tolerable path to

the king’s restoration—tolerable that is to the protestant minority. It was not

an easy path, for the Irish Convention defied the English council’s direction to

bow itself out. It was still unwilling to do so even when the English Conven-

tion opened on 25 April, though on 1 May it published a declaration that the

execution of Charles I had been ‘the foulest murder’ and adjourned for six

weeks. Long before that period elapsed, Charles II had not only been pro-

claimed king in all his three kingdoms but was back on his English throne.

Indeed after the Convention’s crucial vote on May Day it only remained to

bring him home. He chose to meet its emissaries at the Hague, and he was

feted there for a triumphal week while Montagu’s fleet readied itself to carry

him across the Channel. Fairfax was prominent among the twelve members

whom the Convention sent over with its formal invitation to return to his

own, and Charles spent some time with him alone. Monck waited to greet

him at Dover, along with a huge crowd. Charles raised him from his knees

and kissed him, calling him father. The king made his leisurely way to Lon-

don, holding his first privy council at Canterbury and worshipping in its much

delapidated cathedral. He was ‘extremely nauseated’ by the crowd of old cava-

liers who beset him there, clamouring for places or other rewards. At Black-

heath he reviewed five regiments of cavalry, many of whose faces belied the

declaration of their joy at his presence that their commander presented to

him. But his triumphal entry into his capital aroused enormous popular

enthusiasm, and the Londoners’ celebrations lasted three days and nights. In

some provincial towns they went on even longer, and the drunkenness was

sometimes accompanied by vengeful attacks on former enemies’ property

and by the harassment of sectarian congregations. Quakers were attacked in

fifteen counties, and prosecutions for witchcraft, which had fallen off so

markedly since the Civil Wars, climbed for a while sharply again.

15

778 The Collapse of the Good Old Cause 1658–1660

15

On popular reactions to the king’s return see Davies, Restoration of Charles II, pp. 350–4,

Hutton, Restoration, pp. 125–6, and the sources cited in both works.

ch27.y8 27/9/02 12:19 PM Page 778

Nevertheless there is no mistaking the breadth and depth of the rejoicing

that accompanied the Restoration. It represented a return to order and sta-

bility after a year and more in which the quality of government had deter-

iorated to the point of threatening the livelihood of ordinary folk, as well as

undermining the prosperity of the more well-to-do. The reaction was partly

against things that had been unpopular for a dozen years or more: the

unprecedented weight of taxation; the unwanted presence of soldiers in large

numbers; the repeated intervention of the military in civil affairs; the pro-

scription (at least on paper) of the much loved Prayer Book services, the ban

on Christmas, maypoles, stage plays, and other pleasures; the antics of the

extremer sectaries, Quakers especially; and the efforts of the civil magistrate

to promote a reformation of manners. But it has been argued here that during

Cromwell’s rule as Protector, especially after 1655, things had been getting

broadly better, and that the efforts of the royalists to bring back their king,

which (with honourable exceptions) were never very impressive, became fee-

bler and feebler until 1659, partly because there was less discontent to

exploit. If Charles II had been restored by force of arms in (say) 1657 or 1658,

there would undoubtedly have been considerable rejoicing, but it would have

been much less general than in 1660, and tempered by much wider regret for

the Good Old Cause. The Commonwealth perished through its own inepti-

tude and internal strife before any tide of royalist enthusiasm swept its

remnants away.

The Monarchy Restored 779

ch27.y8 27/9/02 12:19 PM Page 779

Epilogue

With the return of the king to his capital the narrative part of this book

comes to an end. Readers who are gluttons for punishment might have expect-

ed it to be rounded off, textbook-fashion, with a summary of the so-called

Restoration settlement. But that is a complex and partly illusory subject, for

the regulation of the return to monarchical government in the state and to an

exclusive Church of England occupied a considerable period of time, and

some matters that really needed to be determined were not settled at all in

Charles II’s lifetime. Even by the end of 1662, the constitutional and eccle-

siastical scenes were taking markedly different turns from what had appeared

to be their direction in the first months of the reign. So I shall take my leave by

addressing, as briefly as I can, three tasks: to tell as a story-teller should what

became of his chief characters; to assess how far the peoples of the three

Stuart kingdoms attained and held on to the objectives for which they had

taken up arms, and finally to answer the question I posed at the beginning,

namely how far, or in what senses, the upheavals that they underwent consti-

tuted a revolution.

To start with the most obvious losers at the Restoration, the Declaration of

Breda left it to parliament to determine who should be excepted from the

promised royal pardon and how they should be punished. The most vulner-

able were the regicides, and of the sixty-nine who had passed sentence of

death on Charles I forty-four were still alive. The most fortunate of these was

‘Dick Ingoldsby, who can neither pray nor preach’,

1

for he not only escaped

punishment but was made a Knight of the Bath at Charles II’s coronation,

thanks to his recent success in routing and capturing Lambert. That was not

the act of a turncoat, for he had been conspicuously loyal to the Protectorate

up to the moment when Lambert’s faction overthrew it. He sat as MP for

Aylesbury from 1660 until his death in 1685. For the rest, the Convention

showed considerable lenity in singling out only seven of the regicides in cus-

tody to be tried for their lives, along with John Cook, the king’s prosecutor,

Colonels Axtell and Hacker, who had commanded the guard at his trial, and

Hugh Peter, whose vehement support of the regicide from the pulpit put him

in royalist eyes on a level with the king’s judges. Among those executed with

them were Thomas Scot and the Fifth Monarchists Thomas Harrison and

1

See above, p. 714.

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 780

Epilogue 781

John Carew, who all bore the public butchery of hanging, drawing, and quar-

tering with conspicuous courage. It has been well said by Ronald Hutton that

‘The regicide itself had been a solemn and tragic ritual: these men died amidst

the atmosphere of a bear-baiting’.

2

Some, perhaps most of them, stayed in

England expressly so that they could bear witness to their cause from the scaf-

fold, but others understandably fled abroad, whether like Whalley and Goffe

to the American colonies or like Hewson and many more to the continent.

Ludlow bravely waited until the Convention had unseated him before he left

for a long exile in Switzerland, in company with other old commonwealths-

men. Okey, Barkstead, and Miles Corbet took refuge together in the Nether-

lands, but George Downing, who had swum with the tide at the Restoration

and won his continuance in his old post as resident in The Hague, secured

their arrest by means akin to entrapment in 1662 and sent them home to suf-

fer the death of traitors. They were not the last to perish that year, for the Cav-

alier Parliament, which had succeeded the Convention, was baying for the

blood of Lambert and Vane, though neither was a regicide and both had been

reprieved in 1660. Both were put on trial. Lambert expressed contrition and

obtained the king’s mercy, if that is the right name for twenty-one more years

of lonely imprisonment in island fortresses, in the course of which he lost his

reason. But Charles had no mercy for Vane, whose death he sought with an

animus that can only be called vindictive, simply because Vane had been such

a persistent and principled opponent of monarchy.

But it would be wrong to dwell on the hardest cases. Most of the regicides

who surrendered and appealed to the king’s mercy were spared, and some

including Fleetwood suffered nothing worse than being disqualified from

public office for life. The same penalty was imposed on such non-regicide

pillars of the Commonwealth as Lenthall, St John, Whitelocke, and Berry.

Marten was in danger of being executed along with the other arch-regicides,

but he defended himself at his trial with great spirit, and it was remembered

that he had interceded for the lives of a number of royalists, so he was sen-

tenced to life imprisonment. He lived for another twenty years, and the tower

in Chepstow Castle where he spent the last twelve of them still bears his name.

He was so poor that according to Anthony à Wood he was ‘glad to take a pot

of ale from any that would give it to him’.

3

There was no spirit left in Hasel-

rig, even though he had not sat in judgement on Charles I. He had been named

to the High Court, but prevented from attending it by his military duties in

Newcastle at the time. Nevertheless his impassioned opposition to monarchy

put his life in danger, and he needed Monck’s promised intercession to secure

his exemption from the ultimate penalty. A broken man, he died in the Tower

2

Hutton, Restoration, p. 134, and see Christopher Hill, The Experience of Defeat (1984),

pp. 69–75.

3

Quoted in Ivor Waters, Henry Marten and the Long Parliament (Chepstow, 1973), p. 71.

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 781

782 Epilogue

in 1661. There were no proceedings against Richard or Henry Cromwell,

whose retirement into obscurity has already been mentioned, but a posthu-

mous vengeance was taken against Oliver. His rotting body and those of Ire-

ton and Bradshaw were taken from their tombs in Westminster Abbey and

publicly hanged in their shrouds, before their skulls were impaled in West-

minster Hall.

Milton paid a less heavy price than he probably feared for his last-ditch lit-

erary stand against the Restoration. One MP did propose that he should be

one of the twenty non-regicides excepted from pardon under the Act of

Indemnity, and though this was not seconded the Commons did order on

16 June that Milton and John Goodwin should be immediately arrested. Curi-

ously, the Commons’ sergeant-at-arms did not execute the order until Novem-

ber, though before then two of Milton’s earlier books in defence of the

Commonwealth were burnt by the common hangman. He was persuaded to

sue out his pardon, which he duly received after the Commons considered his

case on 15 December. He was not troubled again, and Goodwin too obtained

a pardon. As for the latter’s namesake Thomas Goodwin, he and John Owen,

who shared the leadership of the moderate Independents, both formed their

own congregations in post-Restoration London and ministered to them

through thick and thin, far into what was then old age. In 1674 Charles II

gave Owen a private audience and a thousand guineas for the relief of those

suffering under the current penal laws against dissenters. As usual, the king

was more tolerant than his parliament-men and his prelates.

There were rewards for some of the old presbyterians who had never coun-

tenanced the abolition of monarchy. Cromwell’s old general Manchester

became a privy councillor and Lord Chamberlain; Denzil Holles also joined

the council and was made a peer, and Booth became Baron Delamere. There

were knighthoods for Edward Massey and Richard Browne, but rather

strangely nothing for Sir William Waller, though he had been in the Tower as

a royalist conspirator in 1659 and was useful to Monck early in 1660. The

greatest rewards went naturally to those former Cromwellians who had done

most—more indeed than any old royalists except perhaps Hyde and

Ormond—to bring the Restoration about. Monck himself was made Duke of

Albemarle and Captain-General, Montagu became Earl of Sandwich and

Admiral of the Narrow Seas, and both received princely endowments of land.

Both continued their careers as fighting men in the naval wars against the

Dutch, and Montagu perished when his ship was blown up in 1672. Broghill,

who was still under forty when the king came home, was created Earl of

Orrery and a Lord Justice of Ireland, and made some additional reputation as

an author of rhymed tragedies. Sir Charles Coote became Earl of Mountrath,

but died in 1661. His fellow Anglo-Irishman Annesley was made Earl of

Anglesey and rose through a succession of offices to Lord Privy Seal.

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 782

Epilogue 783

The fate of the Scotsmen who have figured prominently in these pages can

be told most conveniently in the context of the plight of their country as a

whole at the Restoration. Of Charles I’s three kingdoms, Scotland had been

the first to take up arms and England the last, so in considering how far each

one achieved and held on to what it had fought for it seems appropriate to

take them in the order Scotland, Ireland, England. In the first two the settle-

ment had more to do with muscle than with justice, for Charles II was under

far less pressure to make concessions to his father’s former opponents than he

had been when he was still winning his way back to England. He was slow to

take any positive steps at all regarding the government of Scotland, but on a

petition from some prominent Scots who had come to London to attend him

he restored it in August 1660 to the Committee of Estates, pending the

election of a Scottish parliament, which met on 1 January 1661. The

Cromwellian union with England was of course assumed to be invalid. Mean-

while he chose men of contrasting political backgrounds as his chief ministers

and officials. The Earl of Lauderdale, who as John Maitland had sat on the

Committee of Both Kingdoms in 1644 but had sided with the king in the sec-

ond Civil War, became the all-powerful Secretary of State for Scottish Affairs

and eventually achieved a dukedom. Glencairn was made Lord Chancellor,

and John Middleton, the former Engager and Lieutenant-General, became the

king’s commissioner for parliament, with an earldom. But the men whom

Charles chose as Treasurer and Justice-General, Crawford-Lindsay and

Cassilis respectively, did not last long because they fell out with him over his

religious policy and lost their offices. Early hopes that Presbyterianism would

be retained were gradually confounded. When eleven Protesters framed a

petition to the king in August, congratulating him on his restoration but

deploring the use of the Prayer Book in his household and reminding him that

he was under obligation to observe the Covenant throughout his dominions,

the Committee of Estates had them arrested (bar one who escaped) and

imprisoned in Edinburgh Castle. One, James Guthrie, who obstinately re-

jected the king’s ecclesiastical authority, was tried for treason by parliament

in 1661, as was the Marquis of Argyll. Both were executed. Johnston of Waris-

ton was marked down for the same fate, but he had fled abroad. He was

captured, brought home, and put to death in 1663.

The elections to the parliament were so managed that it represented royalist

Scotland rather than the nation as a whole, but at least it did not revert to the

early Stuart procedure which had made it a mere rubber stamp for the Lords of

the Articles. Its first session lasted over six months, and it really did debate the

highest matters of state. The voice of opposition, never silent, was increasingly

heard in its successors. Its main measure in 1661 was a comprehensive Act

Rescissory which cancelled the proceedings and enactments of every parlia-

ment since 1633 except that of 1650–1, which had been called by the young

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 783

784 Epilogue

king when he was in Scotland. It thus swept away all the statutory authority

that had supported the National Covenant, the Solemn League and Covenant,

and the whole system of Presbyterian church government as it had evolved dur-

ing and since the troubles of Charles I’s reign. Another act virtually exempted

the nobility and the more substantial lairds from the jurisdiction of the JPs,

whom it reduced to mere agents of the Scottish privy council’s authority.

This privy council was established immediately after the parliament’s first

session ended on 12 July 1661, and its members were named on the king’s

authority alone. It met at Holyroodhouse, but its role was mainly confined to

routine administration. Major decisions of policy were taken in London,

where Lauderdale, the hub round which Scottish affairs revolved, lived per-

manently on the king’s orders, and conferred with Hyde (now Earl of Claren-

don), Monck, Ormond and Manchester, who were tacked on to the Scottish

council as special advisers. It was hence that the council in Edinburgh heard

in September 1651 of the king’s decision to restore episcopacy in Scotland,

and obediently gave effect to it by an act of council. A proclamation followed,

forbidding presbyteries, synods, or kirk sessions to meet without the author-

ization of the bishop, and an act passed on 27 May 1662, soon after parlia-

ment began its second session, completed the restoration of episcopal church

government. Ministers who were not presented by a lawful patron and col-

lated by a bishop, or who declined the oath of allegiance and supremacy, were

to be deprived of their livings, and as a result of these and other decrees

between a quarter and a third of all the parish clergy in Scotland lost their

benefices, mainly in the Presbyterian west and south-west. Laymen too were

subjected to religious tests, for all in public employment were forced to swear

an oath abjuring the Covenants, as well as affirming the unlawfulness of tak-

ing up arms against the king.

So it was that for all those Scots who had fought in the Bishops’ Wars, or as

England’s allies in the first Civil War—indeed for the larger number who sin-

cerely adhered to the Covenants—the Restoration spelt almost total defeat.

Even the Engagers of 1648, and those who fought for Charles II in 1650–1,

would have got more generous terms if they had won, and even the royalists

who had fought with Montrose or Glencairn would have expected a larger

say in the government of their own country than their king and his crony

Lauderdale allowed them. The only mitigations were that the nobility,

despite being jurisdictionally over-privileged, did not retain such an oppres-

sive power over their inferiors and tenantry as they had formerly enjoyed, and

that the restored bishops did not recover much of the political role that had

made them doubly unpopular in the 1620s and 1630s.

Of all who took to arms in the three kingdoms between 1637 and 1642, the

Irish rebels of 1641 were the most comprehensive losers. They had fought for

the free exercise of their catholic faith, for the eligibility of catholics to public

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 784

Epilogue 785

office, for the right of a truly representative Irish parliament to legislate for

their country unfettered by Westminster, and for secure titles to their estates.

Although they had always professed their loyalty, they obtained none of these

things. An Irish parliament did meet in 1661 and sat intermittently until

1666, but apart from a handful of catholic peers in the Lords it was a wholly

protestant body, and its initiative remained shackled by Poynings’ Law. After

its dissolution Ireland did not get another parliament for twenty-three years,

by which time the Glorious Revolution had changed the political scenery in

all three kingdoms. While the Restoration parliament sat it was in no mood

to honour Ormond’s agreement in the peace of 1649 that it should free

catholics from all penalties that hindered the practice of their faith; indeed it

called for a bill to suppress the catholic hierarchy entirely. This was blocked

by the government, and Ormond warmly encouraged a remonstrance,

framed by his ally the Franciscan Peter Walsh, that would have secured reli-

gious freedom for catholics provided that they disclaimed the pope’s power

to absolve subjects from their king’s authority, and affirmed kings to be God’s

lieutenants on earth, whatever their religion. This promising scheme failed

mainly because the majority of the Irish clergy, taking their cue from the Vati-

can, opposed its concessions and partly because Walsh himself would brook

no compromise.

The degree of de facto toleration of unobtrusive catholic worship varied

from province to province, and also from period to period, as the ascendency

of the various parties in England changed. There was seldom any shortage of

priests; in the early 1670s there were said to be 1,000 seculars and 600 regu-

lars in Ireland, but many had little education and they had to minister in mass-

houses rather than in the parish churches that they reasonably thought should

be theirs. They made little progress during Ormond’s first term as Lord Lieu-

tenant from 1662 to 1669 (he had a second from 1677 to 1685), partly

because the Vatican appointed no Irish bishops until it was over. The lieu-

tenancy from 1670 to 1672 of Lord Berkeley, the former Colonel Berkeley

with whom Cromwell and Ireton had negotiated in 1647, brought consider-

able relaxation, including a general synod of Irish catholic bishops in

Dublin, but this brought a protest in 1671 from the Westminster parliament

and a request that the king should expel all priests from Ireland. He did not

do so, but upon a second address in 1673 he issued a proclamation expelling

all bishops and regulars. This caused considerable hardship, but it was only

partially enforced, and matters had returned to normal when the Popish Plot

of 1678 brought further trouble to Irish catholics, culminating in the outra-

geous trial and execution of Archbishop Plunkett of Armagh for high treason.

The situation eased during Charles II’s last years, but most of his reign was a

tense and unsettled time for the Irish catholics and their clergy, a time made

no easier by the latter’s quarrels among themselves.

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 785

It was little better for a high proportion of Irish protestants, perhaps as

many as half. Most protestant ministers in 1660 were Presbyterians or Inde-

pendents, but the Restoration brought with it the immediate re-establishment

of the episcopal Church of Ireland, and the bishops, who were soon made up

to their full number, ejected all incumbents who would not conform to the

Book of Common Prayer. They were reinforced in 1666 by an Act of Uniform-

ity which prescribed a revised version of it, and required all clergy to be epis-

copally ordained and all school-masters to be licensed by a bishop. In 1672 Sir

William Petty reckoned that there were 300,000 protestants in the whole of

Ireland, of whom 100,000 were Scots Presbyterians. He thought that rather

more than half the rest conformed willingly to the established church, which

suggests that the number who did not, the Scots included, totalled more than

half. The discrepancy between the wealth of the prelates, a number of whom

had four-figure incomes (the Archbishop of Armagh’s was over £3,500 a year

in 1668), and the poverty of very many parish clergy, who were forced into

pluralism to survive, was matter for scandal. No wonder that under such a

sick ecclesiastical establishment the Quakers spread and throve in Restora-

tion Ireland.

In civil affairs, the land question posed the most heated conflict and the

most intractable problems, and the attempts to solve them generated a ran-

cour that rumbled all through Charles II’s reign and beyond. It is a story too

complex to be told here in more than the barest outline. The problems were

indeed insoluble in any way compatible with justice, for the claims of the

adventurers and soldiers who had settled in Ireland since the 1640s were

irreconcilable with those of the catholics who had fought loyally for the king

and claimed the benefit of Ormond’s peace of 1649. There was nothing like

enough disposable land in Ireland to satisfy both. Taken as a body, the great-

est permanent losers were the catholic landowners, and they lost on a huge

scale. According to the best evidence we have (and it is imperfect), catholics

owned 59 per cent of the land of Ireland on the eve of the rebellion in 1641,

and they predominated in all but two counties outside Ulster. By 1688 the

proportion had shrunk to 22 per cent, and Galway was the only shire in

which more than half the land was owned by catholics. Dr Simms’s valuable

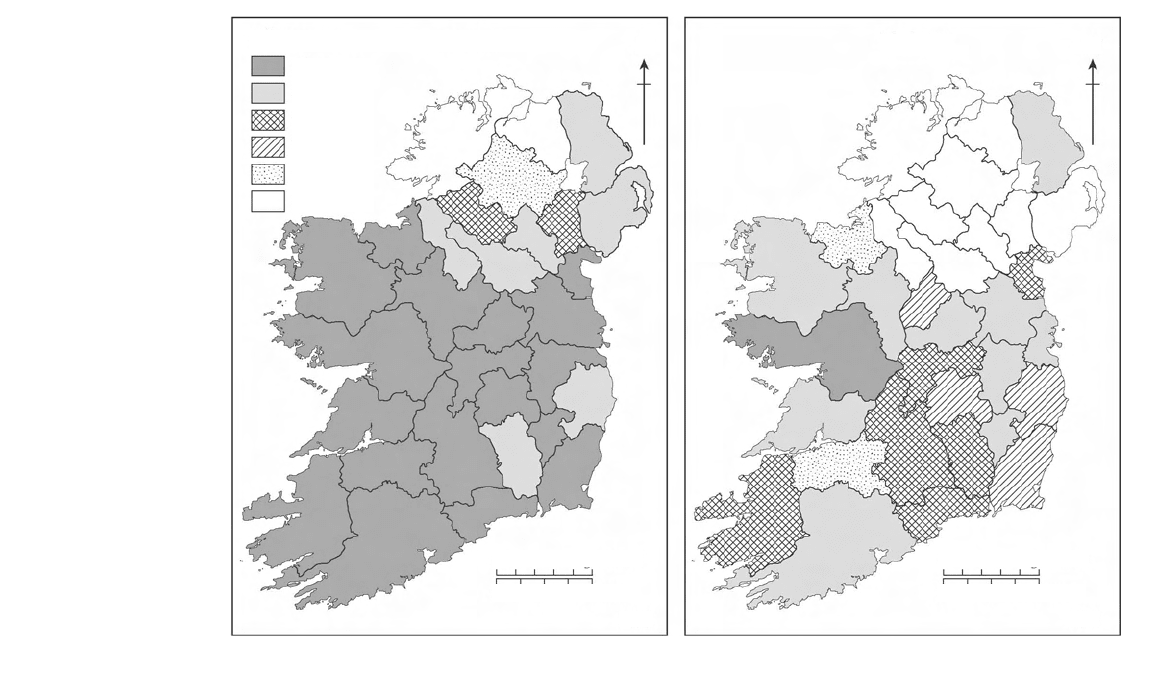

map (opposite) shows the distribution at both dates.

The two chief measures which attempted to tackle the land problem, both

passed by the Cavalier Parliament in Westminster, were the Act of Settlement

of 1662 and the Act of Explanation of 1665. Their broad intention was to

make restitution to Irishmen who had lost their estates through loyalty to the

crown, and where these were currently occupied by Cromwellian settlers to

compensate the latter with land elsewhere. But since there was far too little

land to go round, the Act of Explanation cut the knot by requiring the great

majority of post-1641 adventurers and soldier-settlers to surrender one-third

786 Epilogue

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 786

Epilogue 787

Map 3. Land owned by Catholics in 1641 and 1688.

% by counties Total 59%

Total 59%

N

50 and over

25–49

15–24

10–14

5–9

0–4

0 50 miles

0 40 80 km

1641

0 50 miles

0 40 80 km

1688

N

epilogue.y8 27/9/02 3:22 PM Page 787