Woolrych Austin. Britain in Revolution, 1625-1660

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

but of the sixteen traceable during 1646 the Independents numbered at least

eight and possibly ten.

16

Even at full strength the New Model accounted for less than half the men

under arms in England. Although it absorbed what was left of Essex’s, Man-

chester’s, and Waller’s armies, Massey’s Western Association army and Brere-

ton’s Cheshire brigade were kept up, and the Northern Association forces

were placed in 1645 under Major-General Sydenham Poyntz, a professional

soldier recently returned from service overseas. There were also numerous

local garrisons, as well as the London trained bands. None of these forces was

to play a significant part in what remained of the first Civil War, though they

were to assume considerable political importance after its end.

The delay in getting the New Model ready for action allowed the initiative to

pass to the royalists in the early months of 1645. They took Weymouth in

February, though it was quite soon recovered. Colonel Mytton scored a rare

success for parliament by capturing Shrewsbury on 22 February, but some of

its defenders had come from Ireland, and in accordance of a barbarous ordin-

ance passed in the previous October Mytton hanged thirteen of them.

Rupert promptly retaliated by hanging thirteen parliamentarian prisoners;

the war was getting rougher. Plymouth and Abingdon managed to survive

determined royalist assaults, but Goring’s cavalry captured Farnham, only

thirty-eight miles from London. He was, however, soon forced to draw them

back. More threateningly, the king sent the Prince of Wales with a group of

privy councillors to Bristol, to reanimate the war in the West Country and

create a new field army there. He ordered Goring and his forces to join it, with

the specific aim of besieging the much-contested town of Taunton. Its govern-

or was Robert Blake, earlier the heroic defender of Lyme, who had taken it in

1644 and had already withstood a three-month siege with only a tiny gar-

rison. Now he faced a more formidable threat, but he was partly saved by the

quarrels among his opponents. Goring wangled a commission for himself as

commander-in-chief of all the western forces, and thereby gave great offence

not only to Rupert but to Sir Richard Grenville, who commanded the troops

besieging Plymouth, and to Sir John Berkeley, the governor of Exeter. Nei-

ther Grenville nor Berkeley was willing to take orders from Goring, and they

were on bad terms with each other. Charles’s indulgence to Goring shows

that his growing skill in military strategy was not matched by any improve-

ment in his judgement of men. Goring at his best was a brave and resourceful

commander of cavalry, but drink and debauch were taking their toll of his

talents, and he was all too prone to put his own advancement and reputation

308 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

16

Anne Laurence, Parliamentary Army Chaplains 1642–1651 (Woodbridge, 1990), ch. 4,

esp. p. 54. This work supersedes all previous studies of the subject.

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 308

first. His unwillingness to obey orders which did not promote them was to

hasten the king’s defeat.

Rivals though they were, Goring and Grenville had one thing in common:

their discipline was lax and they let their troops oppress the civilian popula-

tion to a degree that was already causing a backlash. They were not unique in

this, but they were especially notorious. A movement of popular protest was

arising that could at times significantly affect the conduct of the war. Rupert

was one of the first to encounter it. In March 1645 he was sent to relieve

Chester, which was being seriously threatened by Brereton. Leven then dis-

patched 5,000 Scots under David Leslie to reinforce Brereton, and it looked

as though a major battle was impending. Rupert, however, was forced to fall

back by a popular uprising in Herefordshire which threatened his rear. It was

neither for parliament nor for the king, but a spontaneous act of resistance by

exasperated countrymen, who had formed an association to defend them-

selves against lawless, plundering soldiers, whichever side they fought for.

They were called Clubmen because most of them were armed only with

cudgels and farm implements, though some had firearms. Clubmen had first

appeared in Shropshire in the previous December, and in March they rose in

Worcestershire as well as Herefordshire. At this stage they were mostly

yeomen and husbandmen and other small landholders, though quite early

some of the lesser gentry joined their associations. The Herefordshire men

were particularly aggressive; an estimated 15,000 of them virtually laid siege

to Hereford, fired on its royalist defenders and demanded the withdrawal of

all but local troops from the county. Massey marched out of Gloucester to

offer them support and enlist them on the parliamentary side, but to his dis-

gust they would have nothing to do with him. To have closed with him would

have compromised their objectives, which were peace for their community

and freedom from the military presence of either side’s forces. They were

crushed by Rupert’s and Maurice’s combined forces, and their county was

punished when Rupert quartered his troops there and let them loose on it. But

though force of arms stamped out the movement in the Marches for the time

being, further Clubmen risings were to follow: in Wiltshire, Dorset, and

Somerset in the late spring and summer, in south Wales and the border from

August onward, and in Berkshire, Hampshire, and Sussex in the autumn.

The Clubmen associations varied as to whether they were more aggrieved

with the armies in their midst or with the county committees, whose powers

were much increased by the New Model Ordinance, but they all expressed

resentment at the ways in which the demands of war were infringing local

autonomy and rights of property, especially the property of those who had

none to spare. Yet although most were neutralist in origin, they were not

wholly indifferent to the issues between king and parliament, and they

became less so as the rural middling sort who formed their original core were

Towards a Resolution 309

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 309

joined by increasing numbers of gentry, lawyers, and clergy. Their sympathies

differed from region to region, but rather more inclined towards the royalist

cause; indeed they stand as a warning against any facile assumption that in

the countryside the middling sort were as a class basically parliamentarian.

They were moved by an attachment to old ways and to the rule of law, and

many of their declarations called for the retention of the Prayer Book services,

which became formally illegal in March 1645 when parliament prescribed

the exclusive use of the Assembly’s Directory for Worship. They breathed

some of the same grass-roots conservatism, at a more popular level, as the

abortive neutrality pacts of 1642–3, though no one still believed that with a

bit of collective goodwill his county could be spared the ravages of war. Self-

help was needed now, and what nerved untrained countrymen to confront

battle-hardened soldiers was not just exasperation but sheer mass. In most

counties where they appeared they easily outnumbered the locally stationed

troops, claiming as they did (perhaps with some exaggeration) 20,000 adher-

ents in Wiltshire, for example, and 16,000 in Berkshire.

17

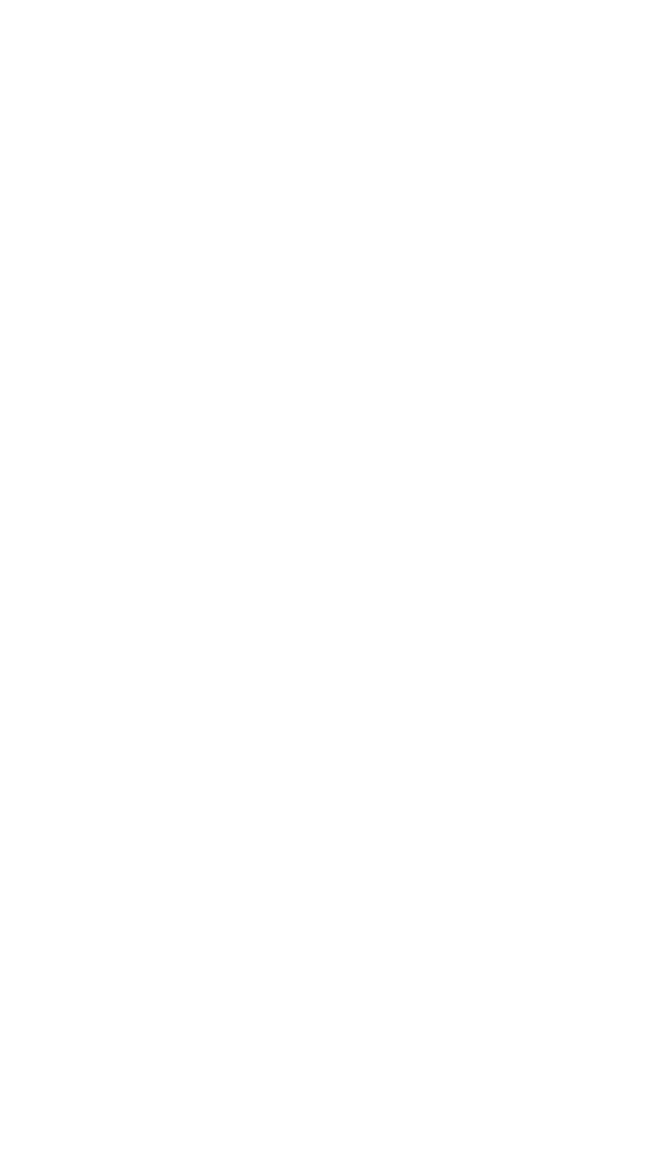

Fairfax was to have much experience of the Clubmen, but they were not

among his problems when he took the field at the end of April, with his army

still at barely half strength. His main impediment was the Committee of Both

Kingdoms, which insisted on directing his operations from Westminster, and

showed the characteristic tendency of chairborne strategists to think defen-

sively and react to the enemy’s last move but one. It ordered him, against his

own judgement, to march to the relief of Taunton, but when he had got all the

way to Blandford it recalled him, directing him to detach six regiments for

Taunton. It was alarmed by the movements of the king’s forces and lured by

a false report that the faithful governor of Oxford, Colonel Will Legge, was

ready to betray the city. Fairfax must have thought that there were better

ways of raising the morale of raw and reluctant infantry recruits than taking

them on long marches with no evident purpose. The chimera of besieging

Oxford before engaging the king’s main army in the field continued to seduce

the committee for weeks, but there was indecision and misjudgement on the

royalist side too. Rupert wanted to march north, first to relieve Chester from

Brereton’s besieging forces and then to attack Leven’s now much reduced

Scottish army, which was besieging Pontefract Castle. But Cromwell was still

in the field with a brigade of horse, making the most of the forty days that the

Self-Denying Ordinance allowed him, and on 25 April he captured Bletching-

ton House, an important garrison only seven miles from Oxford. He went on

310 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

17

Morrill gives the best brief survey of the Clubmen movement in Revolt in the Provinces,

pp. 132–51, 200–4. The earlier version of this book, The Revolt of the Provinces (1976), prints

a number of Clubmen manifestoes (pp. 196–200). See also R. Hutton, The Royalist War Effort

(1982), and D. Underdown, ‘The chalk and the cheese: contrasts among the English Clubmen’,

Past & Present no. 85 (1979), 25–48.

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 310

to harry the outer defences of the city itself, and frustrated the northward

movement of the king’s artillery by driving off most of the draught horses.

This caused Charles to change his plans; he recalled Goring from the west and

summoned all his army, including Maurice’s forces in the border counties

from Worcestershire southward, to a general rendezvous at Stow-on-the-

Wold on 8 May. There he mustered at least 5,000 foot and 6,000 horse, as

much as Fairfax had when he first set out, and the arrival of Sir Marmaduke

Langdale with his northern horse gave him an appreciable advantage in

cavalry. With 5,000 men detached for the relief of Taunton, Fairfax was

temporarily very vulnerable, yet the Committee of Both Kingdoms ordered

him to advance against Oxford.

At Stow, however, the king’s council of war was as usual divided, and it

proceeded to throw away its advantage. Rupert and Langdale wanted to stick

to their plan for a northern campaign, but most of the rest, including the

civilians, pressed for the whole army to move westward and engage Fairfax

while the New Model was still raw and under strength. That surely was what

the parliament and its general had most to fear, but Rupert opposed it strenu-

ously, and he broke what was becoming an impasse by proposing a division

of forces: Goring and his men should be sent westward to check Fairfax,

while the rest of the royal army proceeded northward. It was not a good solu-

tion, but it pleased Goring, whose authority it enhanced, and it was adopted.

It did at least force Brereton to lift the siege of Chester. The Committee of

Both Kingdoms had tried to keep it going by requesting Leven to hasten to

Brereton’s assistance and by ordering all available local forces, including

Lord Fairfax’s Yorkshiremen, to do likewise. But Leven, though he did not

refuse, was deflected by the news of the most brilliant of all Montrose’s vic-

tories at Auldearn. Montrose had owed most of his successes to the unwill-

ingness of reluctant Lowland levies to stand up to the fierce mettle of his

plunder-hungry Highlanders and of Macdonald’s Irishmen, but at Auldearn

he was up against four regular regiments of foot who fought hard, and he left

at least 2,000 of them dead. Leven seriously feared that Montrose might

advance through the Lowlands and eventually join forces with the north-

ward-moving royal army. He had already had to send home nine regiments,

while five were garrisoning Newcastle and five more were besieging Carlisle.

So his way of answering the call of Lancashire and Cheshire was to make a

long northward detour through Westmorland, in case he had to answer an

urgent summons from Scotland. Needless to say Brereton did not receive the

help he needed in time, and Chester’s defenders under Lord Byron were freed

to join the king’s main army, which had reached Market Drayton.

Leven would have been prepared to commit his army against the king’s if

England had sent the New Model north to join him, and that is what the Scot-

tish commissioners urged the Committee of Both Kingdoms to do. They

Towards a Resolution 311

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 311

hoped for a kind of rerun of Marston Moor. But the committee was still lured

by the mirage of an easy siege of Oxford, and the independent politicians

were looking now for an ultimate victory which would owe as little as pos-

sible to the Scots, who had become more and more of a political liability as

their military value had shrunk. After six days of wrangling, the proposal to

send the New Model north was referred to a special committee of both

houses and rejected by one vote. As a compromise, Fairfax was ordered to

send 2,500 of his cavalry and dragoons to assist Leven and to move what he

had left against Oxford. His political masters thus succeeded in splitting his

army into three parts before it was even up to strength, with nearly half his

cavalry posting northward, 4,000 or more men in Taunton (which was duly

relieved, though Goring soon had the relieving force bottled up in the town),

and maybe 10,000 preparing to lay siege to Oxford. By the end of May he had

received at least 4,000 infantry recruits since he first took the field, but he

probably lost 3,000 men through desertion or otherwise in the course of his

gruelling march into Dorset and back.

18

Rupert too had to contend with politically motivated civilian tacticians in

the king’s council of war, but at Market Drayton he guided it towards wiser

decisions than those he had urged at Stow. Byron wanted the royal army to

continue northward, but Rupert, who had been so keen on a northern cam-

paign, was aware that the major part of the divided New Model had returned

as far as Newbury and he was eager to engage it while he could still catch it at

a disadvantage. He had already sent urgent orders to Goring, who was

obsessed with retaking Taunton, to return with his whole force and ren-

dezvous with the main army at Market Harborough. He now successfully

urged that by striking eastward towards the parliamentarian heartland he

would be sure to draw Fairfax off from Oxford, and he hoped on the way to

collect 3,000 Welshmen that Charles Gerrard had been raising and the bulk

of the cavalry from the Newark garrison. Since the royal army already num-

bered at least 11,000 he had a good prospect of giving Fairfax battle on equal

or better terms. If Goring had obeyed, there is no knowing what the outcome

might have been. But Goring was in Bath, indulging in drinking bouts that

incapacitated him for days on end, and he responded to Rupert’s pressing

orders by merely promising that he would come as soon as he had taken

Taunton, which he undertook to do within a few days. That was unlikely,

with his men deserting fast and his siege lines so slack that the defenders were

bringing in provisions almost unhindered. When Charles and Rupert learnt

that Fairfax had actually begun besieging Oxford they commanded Goring

even more urgently to return and relieve it, but in vain.

To draw Fairfax off, they marched against Leicester. It was a wealthy

312 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

18

Gentles, New Model Army, pp. 35–7.

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 312

town, but inadequately garrisoned, and its hastily built fortifications were

compromised by suburban buildings which gave cover to an attacking force.

Its plunder would fill the hungry soldiers’ pockets and still leave plenty over

for the king’s own coffers. Rupert invested it methodically and summoned it

to surrender on 30 May. Not getting an immediate response, he opened fire

with his siege guns in mid-afternoon, and by six they had breached its best

defended quarter, the Newark. At midnight he launched a general assault,

which was resisted with extraordinary tenacity by the defenders, a mere 480

foot and 400 horse, assisted by 900 townsmen in arms. They had to be driven

back street by street until they were finally cornered in the market-place and

forced to surrender. They did not all receive quarter, and women perished in

the night’s slaughter as well as men, for Rupert had lost thirty officers in

storming the town and he was exasperated by its resistance. The ensuing

plunder went on for days, and at the end of it 140 cartloads of booty were

carried off to Newark. It was reported that no royalist prisoner taken

between Leicester and Naseby had less than forty shillings on him—two

months’ pay for a foot soldier. Others who may have taken more made off

home with their spoils and were not seen again.

Leicester’s agony had the expected effect of making the Committee of

Safety abandon the folly of besieging Oxford. Parliament promptly accepted

its recommendation that Fairfax should take the field against the king forth-

with, and it soon freed him from the shackles of constant direction from

Westminster. It simply instructed him to follow the royal army’s movements

and left the rest to his judgement. Not knowing this, the king’s council of war

decided that the relief of Oxford must have first priority; Rupert was over-

borne by Digby and the courtiers, whose ladies in the unprotected city were

badly frightened. But there were better reasons for not being in too great a

hurry to take on the New Model. What with the casualties at Leicester, the

garrison that had to be left there, the desertions of loot-laden soldiers, the

return to Newark of many of the cavalry borrowed from its garrison, and a

mutiny by Langdale’s horse, who rode off when they learnt that the army was

not going to march northward, Charles reckoned that he had barely 4,000

foot and 3,500 horse left. Langdale’s northerners were brought back with

difficulty before his army reached Market Harborough on 5 June, but there

was still no sign of Goring and his men or of Gerrard’s Welsh levies.

That same day Fairfax set off from Oxford. Three long marches took his

army to a rendezvous near Newport Pagnell with the 2,500 men whom he

had sent to support Leven, and on the 8th he held a crucial council of war. He

put two questions to it: how best to bring the king’s army to battle, and how

to fill the vacant post of lieutenant-general of the horse. For that place he

proposed Cromwell, and the assent was unanimous. He sent the 24-year-old

Colonel Robert Hammond posting to Westminster to request the

Towards a Resolution 313

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 313

appointment, to which the Commons immediately agreed. The Lords, whose

concurrence was legally required to exempt Cromwell from the Self-Denying

Ordinance, declined to give it, but the Commons’ assent was enough for Fair-

fax. Cromwell was in Ely, recruiting both horse and foot, and Fairfax at once

sent for him. He was the obvious choice, and a very popular one in the army,

and when he rode into the lines with about 700 horse, early on the day before

the crucial battle of the war, he was greeted ‘with a mighty shout’.

19

Fairfax had equally strong support for seeking battle at the first opportun-

ity, and on the 11th he advanced his headquarters to Stony Stratford, only

twenty-five miles from where the royal army was entrenched in an almost

impregnable position on Borough Hill near Daventry. There it remained

immobile for nearly six days from 7 June onward, mainly because 1,200 cav-

alry had been detached to escort vast quantities of cattle and sheep to Oxford,

and did not rejoin the army until the night of the 11th. Rupert cannot have

approved this, for he knew by the 7th at the latest that the siege of Oxford had

been raised, but he was never sure of his position in the king’s counsels. He

wrote on the 8th to his old friend Will Legge that there had been a plot among

the civilian councillors, Digby and Ashburnham in particular, to persuade

Charles to return to Oxford, so that they could reassert their influence over

him and counter that of ‘the soldiers’, meaning chiefly himself. Charles

sharply rejected the proposal, but Rupert felt insecure.

20

His own judgement

was fallible, however, for he shared the royalists’ facile contempt for ‘the

New Noddle’ (the word could mean booby), and he was poorly informed of

its current strength. He was also quite unaware of its present proximity,

whereas Fairfax had excellent intelligence of royalist movements from

Sir Samuel Luke.

Fairfax and Skippon had much to do during the week before the impend-

ing battle, for many infantry recruits were recent arrivals and were not even

armed when the army left the Oxford lines. A large consignment of muskets

overtook them on the march, but there were still basic skills to be mastered.

Fairfax began his final advance against the royal forces, still in position on

Borough Hill, in foul weather on the 11th. His men slogged all day along

muddy country lanes, avoiding the more frequented roads, and when they

quartered at Wootton that night their approach was still unsuspected. The

rain may have made Rupert’s scouts slack in patrolling, for he was still oblivi-

ous of the New Model’s proximity until late in the next afternoon, when its

‘forlorn hope’ of forward cavalry surprised two of his outposts only two

miles out of Daventry. His army was dispersed and resting, its horses at grass,

while the king was enjoying a hunt in Fawsley Park, several miles away from

its nearest positions.

314 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

19

Abbott, Writings and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell, I, 355–6.

20

Warburton, Memoirs of Prince Rupert, III, 100.

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 314

Great as his advantage was, Fairfax could not attack immediately, because

the day was too far gone and his infantry were too far behind. He quartered

his army around Kislingbury that night, and most of it must have slept in the

wet fields. He himself stayed in the saddle till 4 a.m., riding round his regi-

ments to check their preparedness against a night attack, and then advancing

beyond Flore until he could make out the dim bulk of Borough Hill. There the

king’s army stood to its arms in its prepared positions all night; Fairfax could

see many little fires twinkling, and he rightly deduced that the soldiers were

burning their huts prior to moving off. At about five his invaluable scoutmaster-

general, Leonard Watson, brought him confirmation that it was indeed

retreating, and also a splendid windfall: an intercepted letter from Goring to

Rupert, begging him not to give battle until he could join him, but explaining

that he could not leave the west just yet. It must have rejoiced Fairfax to know

that he could tackle the king’s army and Goring’s forces consecutively rather

than in combination, and that Rupert was deprived of this vital intelligence.

He held a council of war at 6 a.m., and it was actually sitting when the cheer

went up that greeted Cromwell’s arrival. It agreed most readily to pursue the

retreating royalists and make them fight.

By nightfall on the 12th Rupert was at last aware that he had seriously

underestimated the enemy’s numerical strength. He and the king decided to

retreat northward by way of Melton Mowbray to Belvoir Castle, where they

could reinforce themselves from Newark and other Midlands garrisons. To

throw off a possible pursuit they marched westward for some miles, as if for

Warwick, before wheeling north-east for their chosen quarters for the night

around Market Harborough. But all through the 13th a strong detachment of

what was now Cromwell’s cavalry, under his old comrades Henry Ireton and

Thomas Harrison, shadowed the royal army’s movements, and the New

Model advanced on a parallel line with it at a much closer distance than

Rupert knew. He had posted an outer guard of about twenty horse at

Naseby, seven miles from Harborough. They were not very alert, for Ireton

fell on them while they were at supper or playing quoits and captured most of

them. But a few escaped and carried the alarm to headquarters. The king was

roused from his bed, and he and Rupert held a council of war at two in the

morning. The great question, of course, was whether to offer battle, and the

answer was not easy. The alternative proposal was to make speedily for

Leicester, where the addition of its small garrison and the shelter of its

defences, such as they were, would give about 10,000 men a better chance to

hold off at least 15,000. There were great risks either way. A retreat with

Cromwell’s cavalry in close pursuit could have led to a savage mauling, not

least for the 200-odd wagons in the royalist train. But it is very significant that

Rupert, who was usually so eager for action, advised against giving battle. It

was Digby and Ashburnham who pressed for it, arguing that retreat would

Towards a Resolution 315

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 315

demoralize the king’s men, whereas they supposed Fairfax’s to be already dis-

couraged by their failure to take Oxford and by a bloody repulse that they

had lately suffered in an attempt to storm Boarstall House. Even less realist-

ically, they urged that Fairfax should be engaged before he could join forces

with the Scots. The decision rested of course with the king, and he opted for

battle.

It has been said that ‘the Royalist cause committed suicide at Naseby’,

21

but

in fairness one has to consider what might have happened if battle had been

declined. Even if the king had got his army through to Leicester unscathed he

could not shelter there indefinitely, because Fairfax was intent on fighting and

could in the long run muster more reinforcements than he. Now that parlia-

ment had learnt how to deploy its superior resources and found commanders

with the will to win, the terms of war had turned in its favour. And yet if Gor-

ing had obeyed orders and added his troops to the king’s, Naseby would have

been fought on more equal terms, with better if fewer infantry and with a

numerical advantage in cavalry. If the untried New Model’s first battle had

ended in defeat, who can be sure that it would have developed the collective

spirit that took it within a year to total victory? Because of that intercepted

letter, Rupert did not know that Goring was still stuck in Somerset, and may

have advised against an immediate engagement in the assumption that his

forces were well on their way. In deciding to fight, Charles was going against

the odds, but the outcome was not a foregone conclusion.

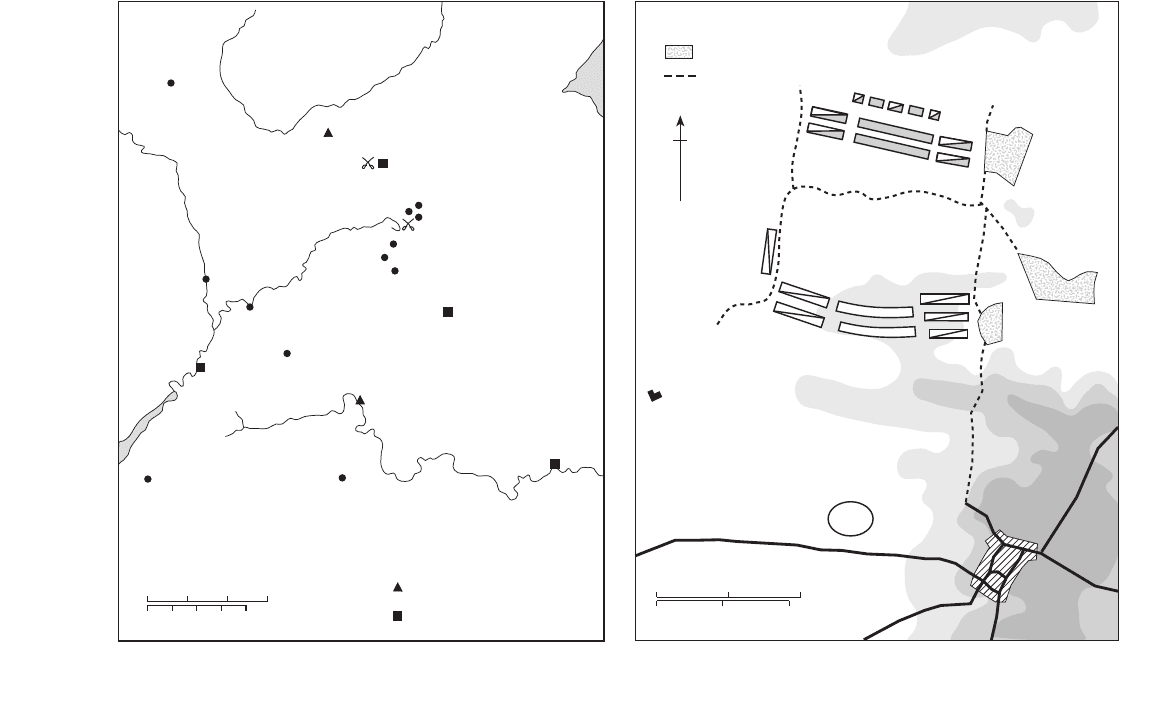

Both armies were on the move in the early hours of 14 June. Fairfax, as he

ranged his on the ridge north of Naseby, did not know yet whether the royal-

ists would accept his challenge, but the appearance of their cavalry in force on

another ridge four miles away reassured him. After much manoeuvring the

two armies drew up about 1,000 yards apart (less at the eastern flank, more

at the western), both near the crests of gentle rises, with the open expanse of

Broad Moor between them. The king had probably slightly more than 9,000

men, the parliamentarians something over 15,000, including Cromwell’s 700

cavalry and Colonel Rossiter’s Lincolnshire regiment, which arrived just after

battle was joined. The royalists were outnumbered mainly in infantry, though

those they had were seasoned soldiers, a high proportion being hard-fighting

Welshman; in cavalry they had about 5,000 against 6,600.

22

As usual, the

foot were ranged mainly in the centre and most of the horse on either flank.

Cromwell commanded on the right, facing Langdale and his northerners and

as much of the Newark horse as had not returned to that garrison. Ireton,

316 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

21

Hutton, Royalist War Effort, p. 178.

22

I have slightly revised the figures I gave in Battles of the English Civil War in the light of

Glenn Foard’s Naseby: The Decisive Campaign (Guildford, 1995), which is now much the fullest

and best account of the battle, and makes fruitful use of archaeological evidence. The figures

exclude officers. For a briefer narrative see Gentles, New Model Army, pp. 55–60.

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 316

Towards a Resolution 317

Market

Drayton

Ashby de la Zouch

Leicester

Market Harborough

East Farndon

Oxendon

Naseby

Guilsborough

Daventry

Kislingbury

Worcester

Evesham

Newport Pagnell

Stow on the wold

Bristol

Gloucester

Oxford

London

Newbury

..

..

Trent

Avon

Thames

Royal garrisons

Parliamentarian garrisons

Severn

Woods

Field boundaries

Naseby

Naseby Hall

THE KING’S RESERVE

BYRON

ASTLEY

LANGDALE

DRAGOONS

IRETON

SKIPPON

CROMWELL

Baggage train

Mill Hill

N

Field of Battle

Map 2. Naseby Campaign of 1645.

-

-

-

ch10.y8 27/9/02 11:11 AM Page 317