Woolrych Austin. Britain in Revolution, 1625-1660

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

their pots and pans and beds and bedding they felt it sorely, for such

things cost far more in relation to their income than in these days of mass-

production. Soldiers also often brought sickness with them, especially typhus

and dysentery; disease was certainly more rife in the war years than before

and after. And when battles were fought, it was local householders who were

left with the care of most of the wounded, and their chances of being paid for

it were problematic: fair, if they were tending parliamentarian casualties after

a parliamentarian victory, otherwise more doubtful.

The 1644 campaigning season began early, with actions involving the forces

acquired by both king and parliament through their recent treaties. Released

by the Cessation, five infantry regiments from Ormond’s army in Ireland had

landed at Chester in November and had been taken under the command of

Lord Byron, the king’s governor of the city. He was aiming to build up a

second royal army in the north-west to match Newcastle’s in the north-east.

He soon took the field against Brereton’s now greatly outnumbered Cheshire

parliamentarians and drove them into Nantwich, to which he laid siege on 13

December. Sir Thomas Fairfax, who was wintering in Lincolnshire, set out to

relieve Brereton with 2,300 horse and dragoons and such infantry as he could

pick up on the way, including many who had fought with him at Adwalton

Moor. As he approached, Byron tried to storm Nantwich on 18 January, but

was repulsed with heavy losses. A week later Fairfax brought him to battle

outside the city and totally defeated him, capturing all his guns and baggage.

Two of the regiments from Ireland broke and ran; 1,500 men were taken pris-

oner, and when offered service under the parliament more than a third—one

account says more than half—promptly accepted. They cannot fairly be

accused of disloyalty, because as Englishmen who had enlisted under a

protestant Dublin government and a protestant general to fight Irish catholic

rebels they would not necessarily see the king as having the better cause in the

Civil War in England. So many others of the men from Ireland simply

made off home that most of the military gains from the Cessation were lost

before January was out, though a few more troops were still expected

at Chester and two regiments were on their way to join Hopton’s army in

the south.

Fairfax had no difficulty in mopping up most of the remaining royalist gar-

risons in Cheshire and Lancashire, while young John Lambert, his most bril-

liant colonel of horse, was fast recovering the clothing towns of the West

Riding. By the spring the only significant royalist outpost in the north-west to

the north of Chester was Lathom House, a great moated castle near Ormskirk

belonging to the Earl of Derby, who was away fighting for the king—at least

for the present, though after the battle of Marston Moor he withdrew to the

Isle of Man. His remarkable French countess, however, a granddaughter of

278 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 278

William the Silent, cousin of the late Elector Palatine and mother of nine chil-

dren, was defying Fairfax’s besieging forces with a garrison of little more

than 300 men. This was the first of two long sieges in which she commanded

the defence in person.

Meanwhile across the Pennines parliament’s alliance with the Scots was

bearing better fruit. A Scottish army, close to its nominal strength of 21,000

men, crossed the Tweed on 19 January under Leven’s command and

advanced slowly towards Newcastle. The veteran general’s sixty-odd years

made him disinclined for unnecessary exertions, but he was immensely experi-

enced in the practical craft of keeping large bodies of men in fighting trim.

There was more dash in his much younger general of the horse David Leslie—

no relation, but schooled like him in the Swedish service. Every regiment in

this army was constituted as a kirk session, with its minister and lay elders,

but for all the praying and preaching to which they were treated Leven’s blue-

bonnets soon gained a bad reputation for plundering and otherwise ill-treating

the civil population. This was no doubt partly due to the anti-Scottish

prejudice of English reporters, but the main explanation is that the Scottish

army’s pay, which England was bound by treaty to furnish, was always in

arrears. Heavy snow and floods slowed Leven’s advance through Northum-

berland, but he met with no other resistance until he launched an assault on

Newcastle on 3 February. There the Scots found that the Marquis who took

his title from that city had arrived in the nick of time to defend it, and they met

with a sharp repulse. They settled around it for the next two months, Leven

thinking it enough to prevent Newcastle and his forces from joining the king.

Two days before that clash of arms Montrose, who was visiting Charles in

Oxford, at last obtained the commission that he had long sought to raise the

Scottish royalists in arms. Formally he was made Lieutenant-General of all

the king’s forces in the northern kingdom, Prince Maurice being appointed

Captain-General, but the command was really his, for Maurice never went to

Scotland. As part of the plan Antrim, who was also in Oxford, was sent to

Ulster with orders to muster 2,000 Irish troops and land them in Argyllshire

by 1 April. Montrose’s return to Scotland in April and May was something of

a fiasco, for he was excommunicated by the Kirk and forced by the hostility

of the Lowlanders to retreat into England again. But his day was to come.

By an intriguing coincidence another commission as Lieutenant-General

was sealed on the same day as Montrose’s. Its recipient was Oliver Cromwell,

and it formalized his position as second-in-command and general of the horse

in Manchester’s Eastern Association army. Essex was incensed by the build-

up of this army, backed as it was by his political opponents; he protested to

the Lords two months later at the reduction of his own to 7,000 foot and

3,000 horse while parliament was financing Manchester’s up to a total of

14,000. With Waller in command of another independent army, now almost

The Conflict Widens 279

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 279

as large as his own, the Lord General’s position was far from comfortable, but

the war party’s dissatisfaction with him was not groundless, and its confi-

dence in the Eastern Association army was to be well justified. But reluctant

though he regrettably was to carry the war to the enemy, Essex could never be

accused of overt disloyalty. Late in January he received a letter from the

Oxford parliament, signed by 44 peers and 118 MPs, urging him to mediate

with the two Houses at Westminster and help to bring about a negotiated

peace. They sent with it a letter addressed by the Oxford to the Westminster

parliament. He declined to present it, but he did return a declaration by the

Lords and Commons at Westminster, promising a pardon to all who returned

to their duty and took the Covenant, of which he enclosed a copy. Nothing on

the face of it could have been more correct, but the almost vice-regal pomp

that Essex was assuming aroused some concern.

The month of March brought mixed fortunes to both sides. For the parlia-

mentarians, Sir John Meldrum laid siege to Newark with a mainly local force

of about 5,000 foot and 2,000 horse, and with Newcastle bottled up by the

Scots in his namesake city the king was in some danger of losing the whole of

the north. But Rupert, who was in Chester to oversee the arrival of the

remaining forces from Ireland, collected a scratch force, led it to Newark

before Meldrum had any idea of his approach, caught him at a hopeless dis-

advantage and forced him to surrender. This was Rupert at his vigorous best;

his booty included over 3,000 muskets, but he had to return most of his men

to the garrisons from which he had taken them and go back to his task of

building up the king’s main army. He spent the rest of the spring in Shrews-

bury, raising and training recruits for it.

In the south the duel between Hopton and Waller was continuing. Hopton

had been shaken by his reverses at Alton and Arundel Castle, and he repeat-

edly asked for reinforcements from Oxford. They came early in March, 1,200

foot and 800 horse under the command of no less than the king’s Captain-

General, Patrick Ruthven, Earl of Forth, who had succeeded Lindsey in the

post. Now in his seventies and somewhat slow, bibulous, and gouty, the old

Scottish professional courteously insisted on treating Hopton as a partner

rather than a subordinate, but the very fact that he had been put in charge of

so modest a force showed that the king’s council of war no longer had quite

its old confidence in Hopton. Together they commanded about 3,200 foot

and 3,800 horse, but Waller had 5,000 foot, including a brigade of London

trained bands, and his 3,000 horse were reinforced on the Committee

of Both Kingdoms’ orders by a whole brigade of cavalry from Essex’s army.

On 4 March the Committee ordered him to march against Hopton, and the

result was the battle of Cheriton, fought on the 29th seven miles east of

Winchester. It went in Waller’s favour, thanks mainly to his superior num-

bers and to the courage and resource shown in a long and fierce cavalry fight

280 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 280

by Sir Arthur Haselrig and his regiment, known as the Lobsters because

unlike nearly all other Civil War cavalry they wore full armour. But the

battle did not reflect much credit on the generalship of either side, and its

immediate results were less positive than they might have been. The royalists

took much the heavier casualties, especially among their officers, but Hopton

got his guns and most of his infantry away in the night to the safe shelter of

Basing House, and Forth escaped westward with his surviving cavalry.

Cheriton did put an end to any further drive eastward by the royalists

through southern England, and it checked a serious attempt by the peace

party at Westminster to make overtures to the king once more. How might

parliament have reacted, one wonders, if Waller had been beaten. As things

were, Charles was thrown on the defensive; he ordered both Forth and

Hopton to rejoin him with their forces in Oxford, where his army currently

numbered only about 10,000. Waller did not pursue them, but moved west-

ward to mop up the remaining garrisons in Hampshire and Wiltshire. He was

deterred, however, from striking further into the West Country by intelli-

gence that the king was massing forces around Marlborough to prevent such

a move, and his infantry were depleted when the London trained-band regi-

ments decided, as they always did sooner or later, that it was time to march

back home.

In mid-April the Committee of Both Kingdoms decided to concentrate all

its forces south of Trent, including Manchester’s Eastern Association army,

in the Aylesbury area, intending a direct attack on Oxford. But already a

more immediate opportunity was beginning to open up in the north. Sir

Thomas Fairfax, having already recovered most of the West Riding, rejoined

his father before Selby, and on 11 April they stormed the town, taking over

3,000 prisoners. Leven was on the march again, having left a sufficient force

to keep Newcastle surrounded. The Marquis of Newcastle, when he heard of

Selby’s fall, gave up disputing the Scots’ advance and drew back his army of

6,000 foot and 5,000 horse to defend York. Leven joined up with the Fair-

faxes near Wetherby on the 20th, and together they agreed to lay siege to

York. Manchester and his army retook Lincoln by storm on 6 May, where-

upon the Committee of Both Kingdoms wisely cancelled their instructions to

him to join Essex and sent him to reinforce the besiegers of York. Essex and

Waller had enough men between them to tackle the king’s Oxford army,

unless Rupert was able to strengthen it considerably, and the threat to York

was more likely to draw him northward. There was not much love lost

between Essex and Waller, but they agreed to co-operate in the operation

against Oxford on the terms that each would direct his own army, with Essex

of course in overall command.

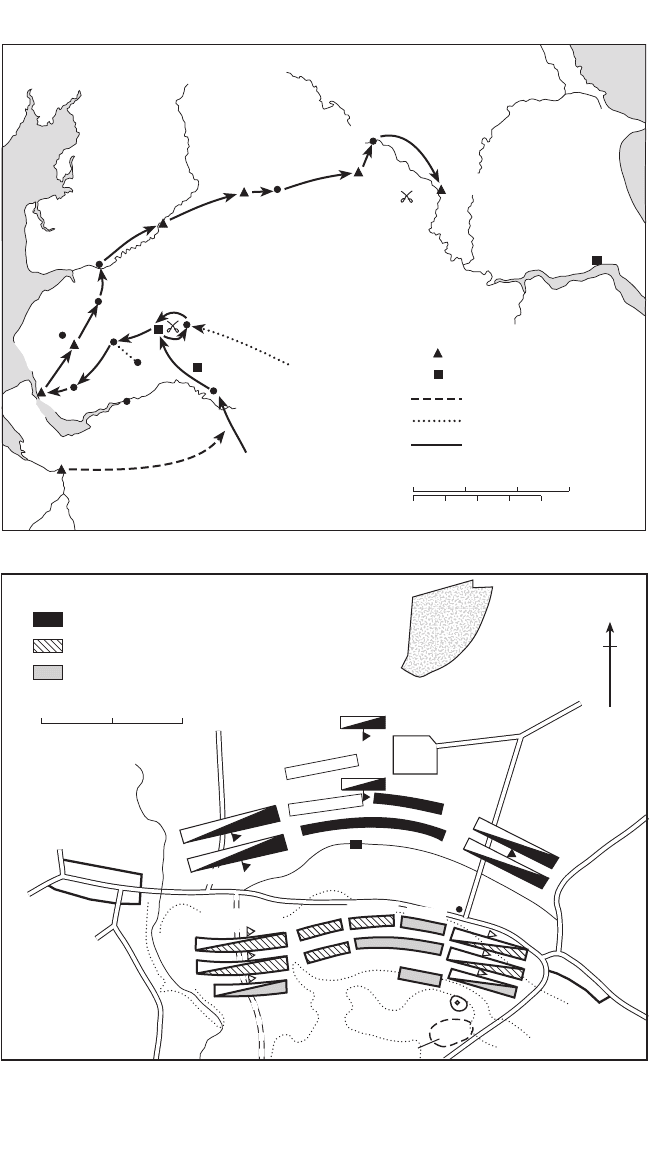

Rupert did indeed respond to the threatening moves of the Scots and the

Fairfaxes. He set off from Shrewsbury on 16 April, but having only 8,000

The Conflict Widens 281

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 281

men, three quarters of them infantry, he needed to collect many more in

Cheshire and Lancashire before he could confront them. He was much

strengthened, especially in cavalry, when he added Byron’s forces to his own

on reaching Chester. He captured Stockport on 25 May and gave the town

over to plunder. His near approach was enough to relieve Lathom House, at

least for the time being. Its besiegers withdrew to Bolton, which he stormed

on the 28th. For daring to resist him, he let his men slaughter 1,600 of its

defenders and sack the town. Next day he introduced himself to the Countess

of Derby at Lathom and presented her with twenty-two standards captured

from her besiegers. The day after, he was joined by Sir Charles Lucas and

George Goring with further reinforcements, including most of Newcastle’s

cavalry, which the marquis sent out of York when he came under siege. Many

Lancashire royalists came in to him, but he met with stubborn resistance at

Liverpool, which he took on 11 June, though only after five days’ bombard-

ment and more than one assault. The defenders paid the now usual price in

butchery and pillage.

By now, however, it was a question whether Rupert’s first priority was to

relieve York or rescue the king. Charles had been forced to strengthen his

main army by pulling in some of Oxford’s outlying garrisons, including the

2,500 in Reading, whose fortifications were dismantled. Essex took the town

over on 19 May, and occupied Abingdon a week later. On that same day

Massey, who from his base in Gloucester had been capturing a whole series

of royalist garrisons in Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, and Wiltshire,

received the surrender of Malmesbury. Charles still had a western army of

about 5,000 in Dorset under Prince Maurice, but it was occupied in besieging

the little town of Lyme (its ‘Regis’ was very much in abeyance), whose heroic

resistance was through no fault of its defenders to distort the whole parlia-

mentarian strategy. By the end of May most of Essex’s army was in and

around Islip, with detachments to the south covering the east banks of the

Thames and Cherwell, while to the west Waller had his headquarters at New-

bridge and forward units in Eynsham and Woodstock. Oxford and the king’s

army were almost surrounded; the gap between Woodstock and Islip was

little more than five miles wide.

The Committee of Both Kingdoms, however, had received false intelli-

gence that Charles intended to come to London and negotiate a peace. In

transmitting this to Essex on 30 May, it also informed him that Lyme was in

desperate straits and instructed him to send immediately a force sufficient to

relieve it, adding that such an operation would be ‘a means . . . to recover the

whole west’.

6

The Committee therefore must take its share of responsibility

for the debacle that followed, for it acted on a report about Charles’s

282 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

6

Quoted in Snow, Essex the Rebel, p. 430.

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 282

intentions which was inherently most improbable, it put the relief of Lyme

before the opportunity to engage his main army at an advantage, and it

encouraged Essex in dreams of conquest in the west. Charles had no intention

of either seeking peace or exposing himself to capture. With admirable auda-

city he mounted a feint attack toward Abingdon, causing Waller to move

south and loosen the noose, then slipped through the gap and headed west

with 3,000 horse and 2,500 foot. By evening on 4 June he and they had got

beyond Burford. Essex and Waller were soon in pursuit, respectively two

days’ and one day’s march behind him, and their chances of bringing him to

battle were still very good. But they held a council of war on the 6th at Stow-

on-the-Wold, with all their commissioned officers present, and there the dis-

astrous decision was taken to separate the two armies. Essex would take the

whole of his to relieve Lyme and reconquer the West Country, while Waller

would go on pursuing the king, combine forces with Massey, and then seek

battle. Waller opposed the plan strenuously but had to submit to Essex’s

express orders, though he protested hard to parliament about them. Essex

had the pretext that he had the heavy guns and the more experience of sieges,

but one cannot but believe that he was drawn by the prospect of a victorious

campaign on his own in what had been Waller’s territory, in co-operation

with his cousin Warwick the Lord Admiral, who was operating off the Dorset

and Devon coasts. He might even capture the queen, who was in Exeter and

expecting very shortly the birth of her fourth child. What a game in high polit-

ics that might open up!

The Committee of Both Kingdoms was appalled by Essex’s decision, and

again directed him to send only a detachment to the help of Lyme, but in a

reply which made his jealousy of Waller all too plain he insisted on sticking

to his course. He duly relieved Lyme, then occupied Weymouth; parliament

bowed to the fait accompli on 25 June and gave its sanction to his further

advance westward. The ruinous consequences will be seen shortly, but if

Essex and Waller had fought and beaten the Oxford army, and supposing

that Rupert’s northern campaign went the way it did, the Civil War could

have been over in 1644.

Charles and his army made their way by 6 June to the relative safety of

Worcester, a garrison city in friendly territory. He did not have too much to

fear now that only Waller was challenging him, and he did not want Rupert

to abandon York to its fate in order to come to his own assistance. But the

orders that he sent to the prince on 14 June were far from unambiguous, and

obviously reflect divisions and misgivings in his council of war. The letter

must have worried the prince sick, and though he never produced it in order

to refute his critics he carried it on him to his dying day. It reads as though it

was deliberately intended to make it possible to blame Rupert if either the

king’s army or the relief of York met with disaster, and if Sir Philip Warwick

The Conflict Widens 283

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 283

is right that Digby drafted it the suspicion is probably justified. But for all its

distracting references to alternative strategies its operative words are clear

enough, and Charles of course signed them: ‘Wherefore I command and con-

jure you . . . that all new enterprises laid aside, you immediately march,

according to your first intention, with all your force to the relief of York’.

Only if he found York already lost, or already freed from its besiegers, or if he

had not enough powder to engage them, was Rupert to march with all his

troops to Worcester, to assist the king and his army.

7

It is clear from the letter

that Charles recognized that Rupert could not relieve York without offering

battle, and he must have known that that would mean fighting against heavy

numerical odds.

Charles and his forces were in fact already on the move and countering

Waller’s threat with a series of daring and successful manoeuvres. They

marched first up the Thames valley to Bewdley, as if heading for Shrewsbury,

but they then doubled back through Worcester, made a rendezvous with the

Oxford garrison at Witney, and next advanced north-eastward as far as

Buckingham. This caused a scare at Westminster that they were about to

descend on Eastern Association territory while its army was far away at York,

and Waller was urgently ordered to prevent it. After sundry manoeuvres,

with the opposing forces marching in sight of each other for hours, Waller

struck on 29 June from a strong position near Cropredy, three miles north of

Banbury. He had as many cavalry as the king (about 5,000) and rather more

infantry, though these again included a brigade of London trained bands. He

caught the royal army on the march and might have given it a severe mauling,

but the untidy and inconclusive battle that ensued went very much in the roy-

alists’ favour, thanks particularly to the dash and initiative shown by their

cavalry under the Earl of Cleveland and Lord Wilmot. Waller took much the

heavier casualties and lost most of his guns. In the aftermath his demoralized

infantry virtually disintegrated; one City regiment deserted en masse, other

companies mutinied or simply made off home. He had strong reason for

telling parliament, as he afterwards did, that the war would never be won by

makeshift armies or part-time soldiers.

Rupert did not know that the king and his army were no longer under

threat when he set off from Preston on his ‘York march’ on 23 June. His

harshness in Stockport and Bolton and Liverpool had not been without pur-

pose, because it had caused the Committee of Both Kingdoms to urge the gen-

erals before York repeatedly to send a strong detachment to the defence of

Lancashire. But they refused to split their forces, and they were right. Inside

York, rations were down to one meal a day for soldiers and civilians alike.

Three mines had been set under strategic points in the walls, in preparation

284 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

7

Eliot Warburton, Memoirs of Prince Rupert and the Cavaliers (3 vols., 1849), II, 436.

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 284

for simultaneous assaults by all three armies, and if Manchester’s major-

general of foot, the Scotsman Lawrence Crawford, had not sprung his

prematurely the city night have fallen before Rupert reached it.

Rupert rested his troops for three nights at Skipton, a royalist garrison.

He had collected so many of them en route that he needed to make sure they

were adequately armed and battle-ready. Setting off again on the 29th,

they had two long days’ marches by way of Otley to Knaresborough, only

seventeen miles from the walls of York. Speed mattered, for Meldrum and

the Earl of Denbigh were on their way with enough local forces from the

Midlands to man the siege works and enable Leven, Fairfax, and Manchester

to march out and give battle. But they were still four days’ march away

when Rupert’s rapid approach caused the three generals to reluctantly aban-

don their lines, their siege guns, and 4,000 pairs of shoes and boots, and to

form lines of battle seven miles west of the city on the broad expanse of

open heath called Marston Moor. They thus covered Rupert’s obvious line

of approach, whether he marched north of the River Nidd or south via

Wetherby.

But Rupert took neither route. He led his army north-west through

Boroughbridge to the first crossing of the River Swale at Thornton Bridge,

and thence joined the road from Thirsk to York. By the time he quartered it

in the forest of Galtres, three miles north of the city, his infantry had marched

twenty-two miles, making all but fifty in the past three days. His appearance

there caused great consternation among the allied commanders, who met in a

council of war that evening. If he chose to fight he could now add the York

garrison to his forces, which they had counted on preventing. They still want-

ed to bring him to battle (at least most of the English officers present did—the

Scots were less keen), but they feared he might slip away southward, perhaps

to add the Newark forces to his own and attack the exposed eastern counties,

perhaps to join up with the king’s army somewhere in the Midlands. That

could spell disaster, with Essex’s army far away in the west and Waller’s in a

state of decomposition. As they saw it, he had good reasons for avoiding bat-

tle, since their combined forces outnumbered his, even when reinforced by

Newcastle’s men in York, by nearly three to two. Nor would he be leaving

York to certain surrender, since by marching south he would draw off at least

Manchester’s army, and Newcastle was expecting reinforcements from

Cumberland and Westmorland. They were of course unaware of the king’s

instructions to him, which he took as a command to fight, and they failed to

appreciate his own eagerness for battle. Even less could they know that

Rupert came to Newcastle that evening and insisted, against the marquis’s

misgivings and the stronger objections of his infantry commander, James

King, Baron Eythin, that the York garrison should come out and fight along-

side his own forces next day.

The Conflict Widens 285

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 285

Consequently the allied generals decided to march their combined armies to

Tadcaster, intending to block Rupert’s southward passage at the crossings of

the Wharfe and Ouse, and their infantry set off from Marston Moor early in

the morning of 2 July. Their foot regiments were strung out for eight miles

along the lanes towards Tadcaster when they became aware that Rupert’s

cavalry was massing in strength on the Moor, clearly intent on battle. The

royalist horse almost equalled theirs in numbers, and included such formidable

commanders as Goring, Byron, Sir Charles Lucas, and Sir Marmaduke Lang-

dale; the allies’ numerical advantage was nearly all in infantry, and in a battle

of this scale, in mainly very open terrain, the infantry rarely decided the out-

come. So although they may have commanded a total of 28,000 men against

perhaps 18,000 (we do not know just how many of the York garrison came

out to fight), their troops were of varying experience and quality, and Rupert

was not wildly rash to engage them. If he could have fired Newcastle with his

own enthusiasm and confidence, and if Eythin had not borne him a grudge

going back to an incident in the German wars long ago and been uncoopera-

tive to the point of obstructiveness, the day might have gone differently. As it

was, when Eythin’s foot were mustered for action many had not returned

from plundering the besiegers’ abandoned lines, and those who did appear

refused to march until they were given their overdue pay. So although

Rupert’s horse were in position by 9 a.m., the infantry were not fully

deployed on the Moor until far into the afternoon.

There for hours the two armies faced each other, the cavalry on the two

flanks no more than 400 yards apart and the foot not much further. From

about two o’clock there was a desultory exchange of artillery fire, but after

five little broke the silence except the chanting of metrical psalms in the

Scottish and parliamentarian ranks. A shallow valley with a ditch running

through it separated the two hosts, and neither seemed willing to abandon its

high ground and charge uphill. Soon after seven Rupert decided that it was

too late for a battle, saying to Newcastle: ‘We will charge them tomorrow

morning’. The marquis retired to his coach for a pipe of tobacco, doubtless

glad of the chance to take shelter because a huge storm was threatening. As

it broke, amid loud thunder and a downpour of hail, the allied armies

advanced together to the charge and crossed the ditch right along its length.

On their right, Cromwell’s Eastern Association cavalry routed that of Byron

opposite, and though Rupert led a counter-charge in person and checked it,

David Leslie’s Scottish horse were in support and came in gallantly to restore

the advantage. Soon the royalist cavalry on the western flank were in flight.

At the other end of the battle, however, Sir Thomas Fairfax’s northern horse

had to advance over very difficult ground, hotly defended, and were eventu-

ally put to flight by Goring, who went on to wreak havoc upon the Scottish

infantry. Many Scots fled the field; indeed at one stage all three generals were

286 War in Three Kingdoms 1640–1646

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 286

The Conflict Widens 287

M

O

O

R

L

A

N

E

N

R

.

O

u

s

e

WilstropWilstropWilstrop

WoodWoodWood

Marston

Hill

Ditch

Marston Field

Tockwith

Long

Marston

MANCHESTER

FAIRFAX

SCOTS

Obelisk

SIR THOMASSIR THOMASSIR THOMAS

FAIRFAXFAIRFAXFAIRFAX

WHITECOATS

WHITE

SIKE

CLOSE

RUPERT’S HORSE

GORING

Cromwell PlumpCromwell PlumpCromwell Plump

Marston

Grange

Baggage

Royalists

Parliamentarians

Scots

S

i

k

e

B

e

c

k

WHITECOATS

Marston Moor

C

R

O

M

W

E

L

L

E

Y

T

H

I

N

Field of Battle

100'

75'

125'

Hull

York

Knaresboro’

Skipton

Clitheroe

Bolton

Manchester

Liverpool

Chester

Boroughbridge

Marston

Moor

Denton

Preston

Crostan

Bury

Ormskirk

Wigan

Leigh

Prescot

Stockport

Warrington

..

..

..

Forest of Galtres

Royalist garrisons

Parliamentarian garrisons

Byron joins Rupert

Northern Horse

Rupert

R.Ribble

Lathom

House

R

.

D

e

r

w

e

n

t

Map 1. Marston Moor Campaign of 1644.

ch9.y8 27/9/02 10:59 AM Page 287