Whetten David A., Cameron Kim S. Developing management skills

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SKILL PRACTICE

Analysis of “Biological Warfare”

QUESTION:ANALYSIS:

Is it a group or individual problem? Group because the task affects many

employees.

Is there a quality requirement? Yes, because one bid may clearly be

better than another.

Does the manager have needed information? No; the manager must obtain

information from others.

Is the problem structured or unstructured? Structured, because standard routines

are involved.

Do subordinates have to accept the Yes, because they will have discretion

decision? in implementation.

Are subordinates likely to accept the Yes, probably, because of the benefit

decision? to the firm.

Does everyone share a common goal? No; whereas all want the firm to be

profitable, some are ideologically

opposed to this kind of business.

Is conflict among subordinates likely? Yes, since ideological factors may

become relevant.

Do subordinates have needed information? No; subordinates are inexperienced.

Choice: Make a decision by yourself, without sharing the problem with subordinates, after

having obtained the necessary information. You may or may not share the problem with

subordinates to discuss alternatives, but regardless, the decision should be yours alone.

EMPOWERING AND DELEGATING CHAPTER 8 487

This page intentionally left blank

489

Building

Effective

Teams and

Teamwork

SKILL

DEVELOPMENT

OBJECTIVES

■ DIAGNOSE AND FACILITATE

TEAM DEVELOPMENT

■ BUILD HIGH-PERFORMANCE

TEAMS

■ FACILITATE TEAM LEADERSHIP

■ FOSTER EFFECTIVE TEAM

MEMBERSHIP

SKILL

ASSESSMENT

■ Team Development Behaviors

■ Diagnosing the Need for Team Building

SKILL

LEARNING

■ Developing Teams and Teamwork

■ The Advantages of Teams

■ Team Development

■ Leading Teams

■ Team Membership

■ Summary

■ Behavioral Guidelines

SKILL

ANALYSIS

■ The

Tallahassee Democrat’s

ELITE Team

■ The Cash Register Incident

SKILL

PRACTICE

■ Team Diagnosis and Team Development Exercise

■ Winning the War on Talent

■ Team Performance Exercise

SKILL

APPLICATION

■ Suggested Assignments

■ Application Plan and Evaluation

SCORING KEYS

AND

COMPARISON DATA

490 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

SKILL

ASSESSMENT

DIAGNOSTIC SURVEYS FOR BUILDING

EFFECTIVE TEAMS

TEAM DEVELOPMENT BEHAVIORS

Step 1: Before you read the material in this chapter, please respond to the following

statements by writing a number from the rating scale below in the left-hand column (Pre-

Assessment). Your answers should reflect your attitudes and behavior as they are now,

not as you would like them to be. Be honest. This instrument is designed to help you dis-

cover your level of competency in building effective teams so you can tailor your learning

to your specific needs. When you have completed the survey, use the scoring key at the

end of the chapter to identify the skill areas discussed in this chapter that are most impor-

tant for you to master.

Step 2: After you have completed the reading and the exercises in this chapter and, ide-

ally, as many as you can of the Skill Application assignments at the end of this chapter,

cover up your first set of answers. Then respond to the same statements again, this time

in the right-hand column (Post-Assessment). When you have completed the survey, use

the scoring key at the end of the chapter to measure your progress. If your score remains

low in specific skill areas, use the behavioral guidelines at the end of the Skill Learning

section to guide further practice.

Rating Scale

1 Strongly disagree

2 Disagree

3 Slightly disagree

4 Slightly agree

5 Agree

6 Strongly agree

Assessment

Pre- Post-

When I am in the role of leader in a team:

______ ______ 1. I know how to establish credibility and influence among team members.

______ ______ 2. I behave congruently with my stated values and I demonstrate a high degree of

integrity.

______ ______ 3. I am clear and consistent about what I want to achieve.

______ ______ 4. I create positive energy by being optimistic and complimentary of others.

______ ______ 5. I build a common base of agreement in the team before moving forward with task

accomplishment.

______ ______ 6. I encourage and coach team members to help them improve.

______ ______ 7. I share information with team members and encourage participation.

______ ______ 8. I articulate a clear, motivating vision of what the team can achieve, along with specific

short-term goals.

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 491

When I am in the role of team member:

______ ______ 9. I know a variety of ways to facilitate task accomplishment in the team.

______ ______ 10. I know a variety of ways to help build strong relationships and cohesion among team

members.

______ ______ 11. I confront and help to overcome negative, dysfunctional, or blocking behaviors by

others.

______ ______ 12. I shift roles from facilitating task accomplishment to helping build trusting relation-

ships among members, depending on what the team needs to move forward.

When I desire to make my team perform well, regardless of whether I am a leader or member:

______ ______ 13. I am knowledgeable about the different stages of team development experienced by

most teams.

______ ______ 14. I help establish clear expectations and purpose as well as help team members feel

comfortable with one another at the outset of a team.

______ ______ 15. I encourage team members to become as committed to the success of the team as to

their own personal success.

______ ______ 16. I help team members become committed to the team’s vision and goals.

______ ______ 17. I help the team avoid groupthink by making sure that sufficient diversity of opinions

are expressed in the team.

______ ______ 18. I can diagnose and capitalize on my team’s core competencies, or unique strengths.

______ ______ 19. I encourage the team to continuously improve as well as to seek for dramatic

innovations.

______ ______ 20. I encourage exceptionally high standards of performance and outcomes that far

exceed expectations.

DIAGNOSING THE NEED FOR TEAM BUILDING

Teamwork has been found to dramatically affect organizational performance. Some man-

agers have credited teams with helping them to achieve incredible results. On the other

hand, teams don’t work all the time in all organizations. Therefore, managers must decide

when teams should be organized. To determine the extent to which teams should be built

in your organization, complete the instrument below.

Think of an organization in which you participate (or will participate) that produces

a product or service. Answer these questions with that organization in mind. Write a

number from a scale of 1 to 5 in the blank at the left; 1 indicates that there is little evi-

dence; 5 indicates there is a lot of evidence. Comparison data is provided at the end of the

chapter.

1. Output has declined or is lower than desired.

2. Complaints, grievances, or low morale are present or are increasing.

3. Conflicts or hostility between members is present or is increasing.

4. Some people are confused about assignments, or their relationships with other people

are unclear.

5. Lack of clear goals and lack of commitment to goals exist.

6. Apathy or lack of interest and involvement by members is in evidence.

7. Insufficient innovation, risk taking, imagination, or initiative exists.

492 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

8. Ineffective and inefficient meetings are common.

9. Working relationships across levels and units are unsatisfactory.

10. Lack of coordination among functions is apparent.

11. Poor communication exists; people are afraid to speak up; listening isn’t occurring;

and information isn’t being shared.

12. Lack of trust exists among members and between members and senior leaders.

13. Decisions are made that some members don’t understand, or with which they don’t

agree.

14. People feel that good work is not rewarded or that rewards are unfairly administered.

15. People are not encouraged to work together for the good of the organization.

16. Customers and suppliers are not part of organizational decision making.

17. People work too slowly and there is too much redundancy in the work being done.

18. Issues and challenges that require the input of more than one person are being faced.

19. People must coordinate their activities in order for the work to be accomplished.

20. Difficult challenges that no single person can resolve or diagnose are being faced.

SOURCE: Adapted from Diagnosing the Need for Team Building, William G. Dyer. (1987) Team Building: Issues

and Alternatives. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley. Reprinted with permission of Addison Wesley.

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 493

SKILL

LEARNING

Developing Teams and Teamwork

Near the home of one of the authors of this book,

scores of Canada geese spend the winter. They fly over

the house to the nature pond nearby almost every

morning. What is distinctive about these flights is that

the geese always fly in a V pattern. The reason for this

pattern is that the flapping wings of the geese in front

create an updraft for the geese that follow. This V pat-

tern increases the range of the geese collectively by

71 percent compared to flying alone. On long flights,

after the lead goose has flown at the front of the V for

a while, it drops back to take a place in the V where

the flying is easier. Another goose then takes over the

lead position, where the flying is most strenuous. If a

goose begins to fly out of formation, it is not long

before it returns to the V because of the resistance it

experiences when not supported by the wing flapping

of the other geese.

Another noticeable feature of these geese is the

loud honking that occurs when they fly. Canada geese

never fly quietly. One can always tell when they are in

the air because of the noise. The reason for the honking

is not random, however. It occurs among geese in the

rear of the formation in order to encourage the lead

goose. The leader doesn’t honk—just those who are

supporting and urging on the leader. If a goose is shot,

becomes ill, or falls out of formation, two geese break

ranks and follow the wounded or ill goose to the ground.

There they remain, nurturing their companion, until it is

either well enough to return to the flock or it dies.

This remarkable phenomenon serves as an apt

metaphor for our chapter on teamwork. The lessons

garnered from the flying V formation help highlight

important attributes of effective teams and skillful

teamwork. For example:

❏ Effective teams have interdependent members.

Like geese, the productivity and efficiency of an

entire unit is determined by the coordinated,

interactive efforts of all its members.

❏ Effective teams help members be more effi-

cient working together than alone. Like geese,

effective teams outperform even the best indi-

vidual’s performance.

❏ Effective teams function so well that they

create their own magnetism. Like geese,

team members desire to affiliate with a team

because of the advantages they receive from

membership.

❏ Effective teams do not always have the same

leader. As with geese, leadership responsibility

often rotates and is shared broadly as teams

develop over time.

❏ In effective teams, members care for and nur-

ture one another. No member is devalued or

unappreciated. All are treated as an integral

part of the team.

❏ Effective teams have members who cheer for

and bolster the leader, and vice versa. Mutual

encouragement is given and received by each

member.

❏ Effective teams have a high level of trust among

members. Members demonstrate integrity and

are interested in others’ success as well as their

own.

Because any metaphor can be carried to extremes,

we don’t wish to overemphasize the similarities

between Canada geese and work teams. On the other

hand, these seven attributes of effective teams do serve

as the nucleus of this chapter. They will help us iden-

tify ways for you to improve your abilities to lead a

team, to be an effective team member, and to foster

effective team processes. Our intent is to identify

proven techniques and skills that will help you func-

tion more effectively in team settings.

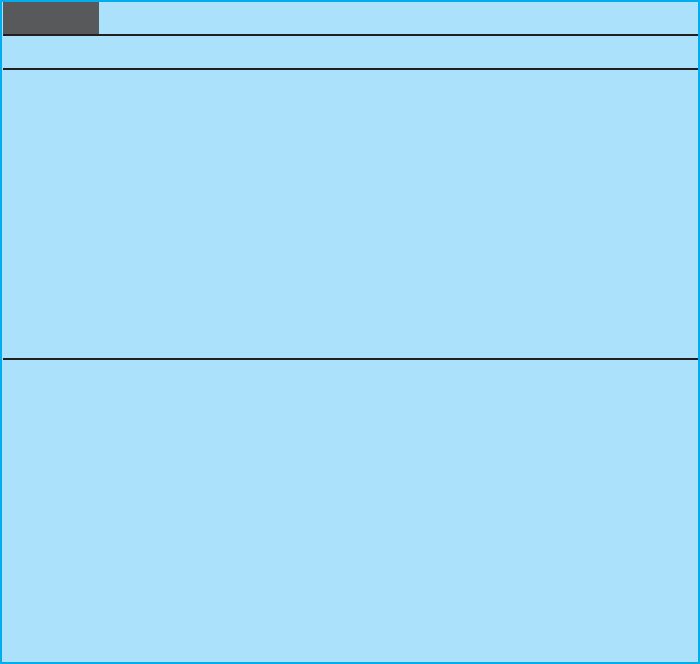

One important reason for this emphasis on teams

is that participation in teams is fun for most people.

There is something inherently attractive about being

engaged in teamwork. Consider, for example, the two

advertisements that appeared next to one another in a

metropolitan newspaper, both seeking to fill the same

type of position. They are reproduced in Figure 9.1.

While neither advertisement is negative or inappropri-

ate, they are noticeably different. Which job would

you rather take? Which firm would you rather work

for? For most of us, the team-focused job seems much

more desirable. This chapter focuses on helping you to

flourish in these kinds of team settings.

494 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

Our Team Needs One Good

Multiskilled Maintenance Associate

American Automotive Manufacturing

P.O. Box 616

Ft. Wayne, Indiana 48606

Include phone number. We respond to all

applicants.

Maintenance Technician/Welder

National Motors Corporation

5169 Blane Hill Center

Springfield, Illinois 62707

Our Team is down one good player. Join our

group of multiskilled Maintenance Associates

who work together to support our assembly

teams at American Automotive Manufacturing.

We are looking for a versatile person with skills

in one or more of the following: ability to set

up and operate various welding machinery,

knowledge in electric arc and M.I.G. welding,

willingness to work on detailed projects for

extended time periods, and general overall

knowledge of the automobile manufacturing

process. Willingness to learn all maintenance

skills a must. You must be a real team player,

have excellent interpersonal skills, and be

motivated to work in a highly participative

environment.

Send qualifications to:

Leading automotive manufacturer looking for

Maintenance Technician/Welder. Position

requires the ability to set up and operate

various welding machinery and a general

knowledge of the automobile production

process. Vocational school graduates or 3–5

years of on-the-job experience required.

Competitive salary, full benefits, and tuition

reimbursement offered.

Interviews Monday, May 6, at the Holiday Inn

South, 3000 Semple Road, 9:00

A.M. to 7:00 P.M.

Please bring pay stub as proof of last

employment.

AMM

NMC

Figure 9.1 A Team-Oriented and a Traditional Advertisement for a Position

The Advantages of Teams

Whether one is a manager, a subordinate, a student, or

a homemaker, it is almost impossible to avoid being a

member of a team. Some form of teamwork permeates

most people’s daily lives. Most of us are members of

discussion groups, friendship groups, neighborhood

groups, sports teams, or even families in which tasks

are accomplished and interpersonal interaction occurs.

Teams, in other words, are simply groups of people

who are interdependent in the tasks they perform,

affect one another’s behavior through interaction, and

see themselves as a unique entity. What we discuss in

this chapter is applicable to team activity in most kinds

of settings, although we focus mainly on teams and

teamwork in employing organizations rather than in

homes, classrooms, or in the world of sports. The prin-

ciples of effective team performance, team leadership,

and team participation we address here, however, are

virtually the same across all these kinds of teams.

For example, empowered teams, autonomous work

groups, semiautonomous teams, self-managing teams,

self-determining teams, crews, platoons, cross-functional

teams, top management teams, quality circles, proj-

ect teams, task forces, virtual teams, emergency response

teams, and committees are all examples of the various

manifestations of teams and teamwork that appear in the

scholarly literature, and research has been conducted

on each of these forms of teams. Our focus is on helping

you develop skills that are relevant in most or all

these kinds of situations, whether as a team leader or a

team member.

Developing team skills is important because of the

tremendous explosion in the use of teams in work orga-

nizations over the last decade. For example, 79 percent

of Fortune 1000 companies reported that they used

self-managing work teams, and 91 percent reported

that employee work groups were being utilized

(Lawler, 1998; Lawler, Mohrman, & Ledford, 1995).

More than two thirds of college students participate in

an organized team, and almost no one can graduate

from a business school anymore without participating

in a team project or a group activity. Teams are ubiqui-

tous in both work life and at school. Possessing the

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 495

❏ Dana Corporation’s Minneapolis valve plant

trimmed customer lead time from six months

to six weeks.

❏ General Mills plants became 40 percent more

productive than plants operating without

teams.

❏ A garment-making plant increased its pro-

ductivity 14 percent by adopting a team-based

production system.

Table 9.1 reports the positive relationships

between employee involvement in teams and several

dimensions of organizational and worker effectiveness.

Lawler, Mohrman, and Ledford (1995) found that

among firms that were actively using teams, both

organizational and individual effectiveness were above

average and improving in virtually all categories of per-

formance. In firms without teams or in which teams

were infrequently used, effectiveness was average or

low in all categories.

Of course, a variety of factors can affect the per-

formance and usefulness of teams. Teams are not

inherently effective just because they exist. A Sports

Illustrated cover story, for example, labeled the Los

Angeles Clippers NBA basketball team the worst team

in the history of professional sports from inception

to the year 2000 (Lidz, 2000)—evidence that just

because a group of talented people get together does

not mean that an effective team can be created.

Hackman (1993) identified a set of common inhibitors

to effective team performance, including reward-

ing and recognizing individuals instead of the team,

not maintaining stability of membership over time, not

providing team members with autonomy, not fostering

interdependence among team members, and failing to

orient all team members. In contradiction to Peters’

comments about the universal utility of teams,

Verespei (1990) observed:

All too often corporate chieftains read the suc-

cess stories and ordain their companies to

adopt work teams—NOW. Work teams don’t

always work and may even be the wrong solu-

tion to the situation in question.

The instrument, called “Diagnosing the Need for

Team Building” in the Skill Assessment section of this

chapter, helps identify the extent to which the work

teams in which you are involved are performing effec-

tively, and the extent to which they need team building.

Often, teams can take too long to make decisions, they

can drive out effective action by becoming too insular,

and they can create confusion, conflict, and frustration

ability to lead and manage teams and teamwork, in

other words, has become a commonplace requirement

in most organizations. In one survey, the most desired

skill of new employees was found to be the ability to

work in a team (Wellins, Byham, & Wilson, 1991).

One noted management consultant, Tom Peters

(1987), even asserted:

Are there any limits to the use of teams? Can we

find places or circumstances where a team

structure doesn’t make sense? Answer: No, as

far as I can determine. That’s unequivocal, and

meant to be. Some situations may seem to lend

themselves more to team-based management

than others. Nonetheless, I observe that the

power of the team is so great that it is often wise

to violate apparent common sense and force a

team structure on almost anything. (p. 306)

One reason for the escalation in the desirability of

teamwork is that increasing amounts of data show

improvements in productivity, quality, and morale when

teams are utilized. Many companies have attributed

their improvements in performance directly to the insti-

tution of teams in the workplace (Cohen & Bailey, 1997;

Guzzo & Dickson, 1996; Hamilton, Nickerson, &

Owan, 2003; Katzenbach & Smith, 1993; Senge, 1991).

For example, by using teams in their organizations:

❏ Shenandoah Life Insurance Company in

Roanoke, Virginia, saved $200,000 annually

because of reduced staffing needs, while

increasing its volume 33 percent.

❏ Westinghouse Furniture Systems increased

productivity 74 percent in three years.

❏ AAL increased productivity by 20 percent, cut

personnel by 10 percent, and handled 10 percent

more transactions.

❏ Federal Express cut service errors by 13 percent.

❏ Carrier reduced unit turnaround time from

two weeks to two days.

❏ Volvo’s Kalamar facility reduced defects by

90 percent.

❏ General Electric’s Salisbury, North Carolina,

plant increased productivity by 250 percent

compared to other GE plants producing the

same product.

❏ Corning cellular ceramics plant decreased defect

rates from 1,800 parts per million to 9 parts per

million.

❏ AT&T’s Richmond operator service increased

service quality by 12 percent.

496 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

Table 9.1 Impact of Involvement in Teams on Organizations and Workers

PERFORMANCE CRITERIA PERCENT INDICATING IMPROVEMENT

Changed management style to more participatory 78

Improved organizational processes and procedures 75

Improved management decision making 69

Increased employee trust in management 66

Improved implementation of technology 60

Elimination of layers of management supervision 50

Improved safety and health 48

Improved union-management relations 47

PERFORMANCE CRITERIA PERCENT INDICATING POSITIVE IMPACT

Quality of products and services 70

Customer service 67

Worker satisfaction 66

Employee quality of work life 63

Productivity 61

Competitiveness 50

Profitability 45

Absenteeism 23

Turnover 22

(N = 439 of the Fortune 1000 firms)

S

OURCE: Impact of involvement in teams on organizations and workers, Lawler, E. E., Mohman, S. A., & Ledford, G. E. (1992). Creating high

performance organizations: Practices and results of employee involvement and total quality in Fortune 1000 companies. Reprinted with permission of

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

for their members. All of us have been irritated by being

members of an inefficient team, a team dominated by a

single person, a team with slothful members, or a team

in which standards are compromised in order to get

agreement from everyone. The common adage that “a

camel is a horse designed by a team” illustrates one of

the many potential liabilities of a team.

On the other hand, a great deal of research has

been conducted to identify the factors associated with

high performance in teams. Factors such as team com-

position (e.g., heterogeneity of members, size of the

team, familiarity among team members), team motiva-

tion (e.g., team potency, team goals, team feedback),

team type (e.g., virtual teams, cockpit crews, quality cir-

cles) and team structure (e.g., team member autonomy,

team norms, team decision-making processes) have

been studied to determine how best to form and lead

teams (see comprehensive reviews by Cohen & Bailey,

1997; Guzzo & Dickson, 1996; Hackman, 2003).

Several thousand studies of groups and teams have

appeared in just the last decade. Self-managing work

teams, problem-solving teams, therapy groups, task

forces, interpersonal growth groups, student project

teams, and many other kinds of teams have been stud-

ied extensively. Studies have ranged from teams meet-

ing for just one session to teams whose longevity

extends over several years. Membership in teams has

varied widely, ranging from children to aged people, top

executives to line workers, students to instructors, vol-

unteers to prison inmates, professional athletes to play-

ground toddlers. The analyses have included a variety

of predictors of performance such as team-member

roles, unconscious cognitive processes, group dynamics,

problem-solving strategies, communication patterns,

leadership actions, interpersonal needs, decision-making

quality, innovativeness, and productivity (e.g., Ancona &

Caldwell, 1992; Gladstein, 1984; Senge, 1991; Wellins

et al., 1991).