Whetten David A., Cameron Kim S. Developing management skills

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 517

to agree with anyone’s comments” is more effec-

tive than “You have always been a problem in

this team.”

❏ Focus feedback on sharing ideas and informa-

tion rather than giving advice. Explore alterna-

tives together. Unless requested, avoid giving

direct instructions and demands. Instead, help

recipients identify changes and improvements

themselves. For example, “How do you sug-

gest we can break this logjam and move for-

ward?” is more effective than “This is what we

must do now.”

❏ Focus feedback on the amount of information

that the recipient can use, rather than on the

amount you might like to give. Information

overload causes people to stop listening. Not

enough information leads to frustration and

misunderstanding. For example, “You seem to

have reached a conclusion before all the facts

have been presented” is more effective than

“Here are some data you should consider, and

here are some more, and here are some more,

and here are some more.”

❏ Focus feedback on the value it may have to the

receiver, not on the emotional release it pro-

vides for you. Feedback should be for the good

of the recipient, not merely for you to let off

steam. For example, “I must say that your

excessive talking is very troublesome to me and

not helpful to the group” is more effective than

“You are being a jerk and are a big cause of our

team’s difficulty in making any progress.”

❏ Focus feedback on time and place so that per-

sonal data can be shared at appropriate times.

The more specific feedback is, or the more it

can be anchored in a specific context, the more

helpful it can be. For example, “During a break

I would like to chat with you about some-

thing” is more effective than “You think your

title gives you the right to force the rest of us to

agree with you, but it’s just making us angry.”

INTERNATIONAL CAVEATS

These team member skills may require some modifica-

tion in different international settings or with teams

comprised of international members (Trompenaars &

Hampen-Turner, 1998). Whereas the team member

skills discussed above have been found to be effective

in a global context, it is naïve to expect that everyone

will react the same way to team member roles.

For example, in cultures that emphasize affectivity

(e.g., Iran, Spain, France, Italy, Mexico), personal con-

frontations and emotional displays are more acceptable

than in cultures that are more neutral (e.g., Korea,

China, Singapore, Japan), where personal references

are more offensive. Humor and displaying enthusiastic

behavior is also more acceptable in affective cultures

than neutral cultures. Similarly, status differences are

likely to play a more dominant role in ascription-

oriented cultures (e.g., Czech Republic, Egypt, Spain,

Korea), than in achievement-oriented cultures (e.g.,

United States, Norway, Canada, Australia, United

Kingdom), in which knowledge and skills tend to be

more important. Appealing to data and facts in the

latter cultures will carry more weight than in the

former cultures. Some misunderstanding may also

arise, for example, in cultures emphasizing different

time frames. Whereas some cultures emphasize just-

in-time, short-term time frames (e.g., United States),

others emphasize long-term future time frames (e.g.,

Japan). The story is told of the Japanese proposal to

purchase Yosemite National Park in California. The

first thing the Japanese submitted was a 250-year busi-

ness plan. The reaction of the California authorities

was, “Wow, that’s 1,000 quarterly reports.” The urgency

to move a team forward toward task accomplishment,

in other words, may be seen differently by different

cultural groups. Some cultures (e.g., Japan) are more

comfortable spending substantial amounts of time on

relationship-building activities before moving toward

task accomplishment.

Summary

All of us are members of multiple teams—at work, at

home, and in the community. Teams are becoming

increasingly prevalent in the workplace and in the

classroom because they have been shown to be power-

ful tools to improve the performance of individuals and

organizations. Consequently, it is important to become

proficient in leading and participating in teams. It is

obvious that merely putting people together and giving

them an assigned task does not make them into a

team. Students often complain about an excessive

amount of teamwork in business schools, but most of

it is less real teamwork than a repetitive experience of

aggregating people together and assigning them a task.

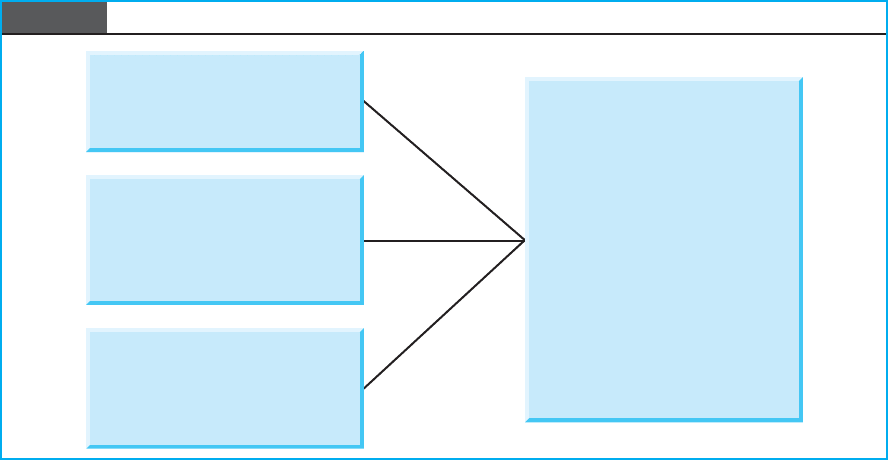

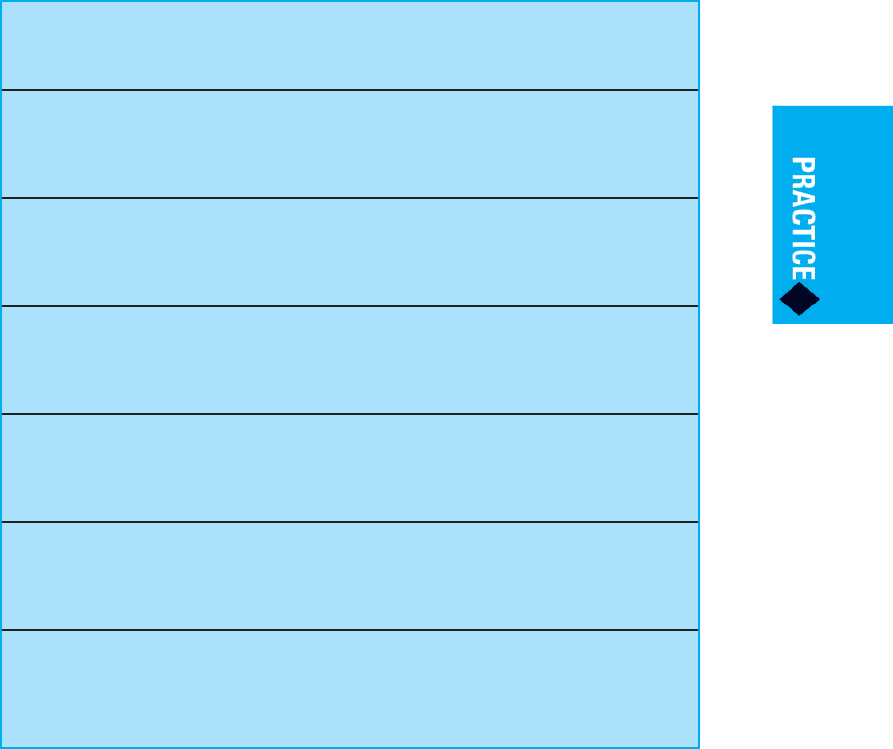

In this chapter we have reviewed three types of team

skills: diagnosing and facilitating team development,

leading a team, and being an effective team member.

Figure 9.4 illustrates the relationship of these three key

skills to high performing team performance. These

three skills are ones that you have no doubt engaged in

518 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

before, but to be a skillful manager, you will need to

hone your ability to perform each of these skill activi-

ties competently.

Behavioral Guidelines

1. Learn to diagnose the stage in which your

team is operating in order to help facilitate

team development and perform your role

appropriately. Know the key characteristics of

the forming, norming, storming, and perform-

ing stages of development.

2. Provide structure and clarity in the forming

stage, support and encouragement in the

norming stage, independence and exploration

in the storming stage, and foster innovation

and positive deviance in the performing stage.

3. When leading a team, first develop credibility as a

prerequisite to having team members follow you.

Figure 9.4 Management Skills for High-Performing Teams

4. Based on your established credibility, establish

two types of goals for and with your team:

SMART goals and Everest goals.

5. As a team member, facilitate task performance

in your team by encouraging the performance of

different roles listed in Table 9.5.

6. As a team member, facilitate the development

of good relationships in your team by encour-

aging the performance of different roles listed

in Table 9.6.

7. When encountering team members who block

the team’s performance with disruptive behav-

iors, confront the behavior directly and/or iso-

late the disruptive member.

8. Provide effective feedback to unhelpful team

members that has characteristics listed in

Table 9.7.

• Desired outcomes

• Shared purpose

• Accountability

• Blurred distinctions

• Coordinated roles

• Efficiency and participation

• High quality

• Creative continuous

improvement

• Credibility and trust

• Core competence

• Develop credibility

• Articulate a vision

• Play task-facilitation roles

• Play relationship-building roles

• Provide feedback

• Diagnose stage development

• Foster team development

and high performance

Leading Teams

Team Membership

Team Development

High-Performing Teams

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 519

SKILL

ANALYSIS

CASES INVOLVING BUILDING

EFFECTIVE TEAMS

The Tallahassee Democrat’s ELITE Team

Katzenbach and Smith (1993, pp. 67–72), as part of their extensive research on teams,

observed the formation of a team at the Tallahassee Democrat, the only major newspaper

left in Tallahassee, Florida. Here is their description of how the team, which called itself

“ELITE Team,” performed over time. All incidents and names are factual. As you read the

description, look for evidence of team development stages.

Fred Mott, general manager of the Democrat, recognized [the declining profitability

and distribution of most major metropolitan newspapers] earlier than many of his

counterparts. In part, Mott took his lead from Jim Batten, who made “customer

obsession” the central theme of his corporate renewal effort shortly after he became

Knight-Ridder’s CEO. But the local marketplace also shaped Mott’s thinking. The

Democrat was Tallahassee’s only newspaper and made money in spite of its customer

service record. Mott believed, however, that further growth could never happen

unless the paper learned to serve customers in ways “far superior to anything else in

the marketplace.” The ELITE Team story actually began with the formation of another

team made up of Mott and his direct reports. The management group knew they

could not hope to build a “customer obsession” across the mile-high barriers isolating

production from circulation from advertising without first changing themselves. It had

become all too common, they admitted, for them to engage in “power struggles and

finger pointing.”

Using regularly scheduled Monday morning meetings, Mott’s group began to

“get to know each other’s strengths and weaknesses, bare their souls, and build a

level of trust.” Most important, they did so by focusing on real work they could do

together. For example, early on they agreed to create a budget for the paper as a

team instead of singly as function heads.

Over time, the change in behavior at the top began to be noticed. One of the

women who later joined the ELITE Team, for example, observed that the sight of

senior management holding their “Monday morning come-to-Jesus” meetings really

made a difference to her and others. “I saw all this going on and I thought, ‘What are

they so happy about?’”

Eventually, as the team at the top got stronger and more confident, they forged

a higher aspiration: to build customer focus and break down the barriers across the

broad base of the paper....

A year after setting up the new [team], however, Mott was both frustrated and

impatient. Neither the Advertising Customer Service department, a series of cus-

tomer surveys, additional resources thrown against the problem in the interim, nor

any number of top management exhortations had made any difference. Ad errors

persisted, and sales reps still complained of insufficient time with customers. In fact,

the new unit had turned into another organizational barrier.

Customer surveys showed that too many advertisers still found the Democrat

unresponsive to their needs and too concerned with internal procedures and dead-

lines. People at the paper also had evidence beyond surveys. In one instance, for

520 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

example, a sloppily prepared ad arrived through a fax machine looking like a “rat had

run across the page.” Yet the ad passed through the hands of seven employees and

probably would have found its way into print if it had not been literally unreadable!

As someone commented, “It was not anyone’s job to make sure it was right. If they

felt it was simply their job to type or paste it up, they just passed it along.” This par-

ticular fax, affectionately know as the “rat tracks fax,” came to symbolize the essen-

tial challenge at the Democrat. . . .

At the time, Mott was reading about Motorola’s quality programs and the goal of

zero defects. He decided to heed Dunlap’s advice by creating a special team of work-

ers charged with eliminating all errors in advertisements. Mott now admits he was

skeptical that frontline people could become as cohesive a team as he and his direct

reports. So he made Dunlap, his trusted confidante, the leader of the team that took

on the name ELITE for “ELIminate The Errors.”

A year later, Mott was a born-again believer in teams. Under ELITE’s leadership,

advertising accuracy, never before tracked at the paper, had risen sharply and stayed

above 99 percent. Lost revenues from errors, previously as high as $10,000 a month,

had dropped to near zero. Ad sales reps had complete confidence in the Advertising

Customer Service department’s capacity and desire to treat each ad as though the

Democrat‘s existence were at stake. And surveys showed a huge positive swing in

advertiser satisfaction. Mott considered all of this nothing less than a minor miracle.

The impact of ELITE, however, went beyond numbers. It completely redesigned

the process by which the Democrat sells, creates, produces, and bills for advertise-

ments. More important yet, it stimulated and nurtured the customer obsession and

cross-functional cooperation required to make the new process work. In effect, this

team of mostly frontline workers transformed an entire organization with respect to

customer service.

ELITE had a lot going for it from the beginning. Mott gave the group a clear per-

formance goal (eliminate errors) and a strong mix of skills (12 of the best people

from all parts of the paper). He committed himself to follow through by promising, at

the first meeting, that “whatever solution you come up with will be implemented.” In

addition, Jim Batten’s customer obsession movement helped energize the task force.

But it took more than a good sendoff and an overarching corporate theme to

make ELITE into a high-performance team. In this case, the personal commitments

began to grow, unexpectedly, over the early months as the team grappled with its

challenge. At first, the group spent more time pointing fingers at one another than

coming to grips with advertising errors. Only when one of them produced the famous

“rat tracks fax” and told the story behind it did the group start to admit that

everyone—not everyone else—was at fault. Then, recalls one member, “We had some

pretty hard discussions. And there were tears in those meetings.”

The emotional response galvanized the group to the task at hand and to one

another. And the closer it got, the more focused it became on the challenge. ELITE

decided to look carefully at the entire process by which an ad was sold, created, printed,

and billed. When it did, the team discovered patterns in the errors, most of which could

be attributed to time pressures, bad communication, and poor attitude....

Commitment to one another drove ELITE to expand its aspirations continually.

Having started with the charge to eliminate errors, ELITE moved on to break down

functional barriers, then to redesigning the entire advertising process, then to refin-

ing new standards and measures for customer service, and, finally, to spreading its

own brand of “customer obsession” across the entire Democrat....Inspired by

ELITE, for example, one production crew started coming to work at 4

A.M. to ease

time pressures later in the day....

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 521

To this day, the spirit of ELITE lives on at the Democrat. “There is no beginning and

no end,” says Dunlap. “Every day we experience something we learn from.” ELITE’s spirit

made everyone a winner—the customers, the employees, management, and even

Knight-Ridder’s corporate leaders. CEO Jim Batten was so impressed that he agreed to

pay for managers from other Knight-Ridder papers to visit the Democrat to learn from

ELITE’s experience. And, of course, the 12 people who committed themselves to one

another and their paper had an impact and an experience none of them will ever forget.

SOURCE: The Tallahassee Democrat’s Elite Team Katzenbach, Jon R. and Douglas K. Smith

(1993) The Wisdom of Teams. Harvard Business School Press, pages 67–72.

Discussion Questions

1. What were the stages of development of the ELITE Team? Identify specific

examples of each of the four stages of team development in the case.

2. How do you explain the team’s reaching a high-performance condition? What were

the major predictive factors?

3. Why didn’t Mott’s top management team reach a high level of performance? What

was his team lacking? Why was an ELITE team needed?

4. Make recommendations about what Mott should do now to capitalize on the ELITE

Team experience. If you were to become a consultant to the Tallahassee Democrat,

what advice would you give Mott about how he can capitalize on team building?

The Cash Register Incident

Read the following scenario by yourself. Then complete a three-step exercise, the first

two steps by yourself, and the third step with a team. A time limit is associated with

each step.

A store owner had just turned off the lights in the store when a man appeared and

demanded money. The owner opened a cash register. The contents of the cash register were

scooped up, and the man sped away. A member of the police force was notified promptly.

Step 1: After reading these instructions, close your book. Without looking at the

scenario, rewrite it as accurately as you can. Describe the incident as best you can

using your own words.

Step 2: Assume that you observed the incident described in the paragraph above.

Later, a reporter asks you questions about what you read in order to write an article

for the local newspaper. Answer the questions from the reporter by yourself. Do not

talk with anyone else about your answers. Put a Y, N, or DK in the response column.

Since reporters are always pressed for time, take no more than two minutes to com-

plete step 2.

Answer

Y Yes, or true

N No, or false

DK Don’t know, or there is no way to tell

Step 3: The reporter wants to interview your entire team together. As a team, discuss

the answers to each question and reach a consensus decision—that is, one with which

everyone on the team agrees. Do not vote or engage in horse-trading. The reporter

wants to know what you all agree upon. Complete your team discussion in 10 minutes.

522 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

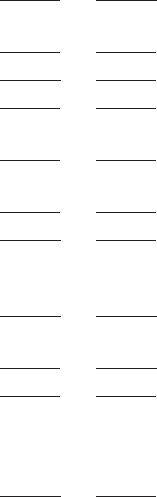

Statements About the Incident

“As a reporter, I am interested in what happened in this incident. Can you tell me

what occurred? I’d like you to address the following eleven questions.”

Statement

Alone Team

1. Did a man appear after the owner turned off his store

lights?

2. Was the robber a man?

3. Is it true that the man did not demand money?

4. The man who opened the cash register was the owner,

right?

5. Did the store owner scoop up the contents of the cash

register?

6. OK, so someone opened the cash register, right?

7. Let me get this straight, after the man who demanded

the money scooped up the contents of the cash register,

he ran away?

8. The contents of the cash register contained money, but

you don’t know how much?

9. Did the robber demand money of the owner?

10. OK, by way of summary, the incident concerns a series

of events in which only three persons are involved: the

owner of the store, a man who demanded money, and a

member of the police force?

11. Let me be sure I understand. Is it true that the following

events occurred: Someone demanded money, the cash

register was opened, its contents were scooped up, and a

man dashed out of the store?

When you have finished your team decision making and mock interview with the

reporter, the instructor will provide correct answers. Calculate how many answers

you got right as an individual, and then calculate how many right answers your team

achieved. Also go back and compare your own description of the incident with the

actual wording of the scenario. How did you do? How accurate were you in your

description?

Discussion Questions

1. How many individuals did better than the team as a whole? (In general, more than

80 percent of people do worse than the team.)

2. What changes would be needed in order for your team score to be even better?

3. How do you explain the superior performance of most teams over even the best

individuals?

4. Under what conditions would individuals do better than teams in making decisions?

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 523

SKILL

PRACTICE

EXERCISES IN BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS

Team Diagnosis and Team Development Exercise

In order to help you develop the ability to diagnose team stage development, consider a

team in which you are now a member. If you belong to a team as part of this class, select

that one. You may also select a team at your employment, in your church or community,

or a team in another class in school. Complete the following three-step exercise:

Step 1: Use the following questions to help you determine the stage of development in

which your team is operating. Create a score for your team for each stage of development.

Identify the stage in which the team seems to operate the most.

Step 2: Identify what actions or interventions would lead your team to the next higher

stage of development. Specify what dynamics need to change, what team members need

to do, and/or how the team leader could foster more advanced team development.

Step 3: Share your scores and your suggestions with others in class in a small-group set-

ting, and add at least one good idea from someone else’s diagnosis to your own design.

Use the following scale in your rating of your team right now.

Rating Scale

1 Not typical at all of my team

2 Not very typical of my team

3 Somewhat typical of my team

4 Very typical of my team

Stage 1

1. Not everyone is clear about the objectives and goals of the team.

2. Not everyone is personally acquainted with everyone else in the team.

3. Only a few team members actively participate.

4. Interactions among team members are very safe or somewhat

superficial.

5. Trust among all team members has not yet been established.

6. Many team members seem to need direction from the leader in

order to participate.

Stage 2

7. All team members know and agree with the objectives and goals of

the team.

8. Team members all know one another.

9. Team members are very cooperative and actively participate in the

activities of the team.

10. Interactions among team members are friendly, personal, and

nonsuperficial.

524 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

11. A comfortable level of trust has been established among team members.

12. A strong unity exists in the team, and team members feel very much

a part of a special group.

Stage 3

13. Disagreements and differing points of view are openly expressed by

team members.

14. Competition exists among some team members.

15. Some team members do not follow the rules or the team norms.

16. Subgroups or coalitions exist within the team.

17. Some issues create major disagreements when discussed by the

team, with some members on one side and others on the other side.

18. The authority or competence of the team leader is being questioned

or challenged.

Stage 4

19. Team members are committed to the team and actively cooperate to

improve the team’s performance.

20. Team members feel free to try out new ideas, experiment, share

something crazy, or do novel things.

21. A high level of energy is displayed by team members and expecta-

tions for performance are very high.

22. Team members do not always agree, but a high level of trust exists

and each person is given respect, so disagreements are resolved

productively.

23. Team members are committed to helping one another succeed and

improve, so self-aggrandizement is at a minimum.

24. The team can make fast decisions without sacrificing quality.

Scoring

Add up the scores for the items in each stage of team development. Generally, one stage

clearly stands out as having the highest scores. Team stages develop sequentially, so the

highest stage in which scores occur is usually the dominant stage of development. Based

on these scores, identify ways to move the team to the next level.

Total of Stage 1 items

Total of Stage 2 items

Total of Stage 3 items

Total of Stage 4 items

Winning the War on Talent

In this exercise, you will form teams of six members. Your team will have an overall objec-

tive to achieve, and each team member will have individual objectives. The exercise is

accomplished in seven steps and it should take a total of 50 minutes to complete steps 1

through 6.

Step 1: In your team, read the scenario on the next page about the problem of attracting

and retaining talented employees in twenty-first century organizations. Your team

objective is to generate two innovative but workable ideas for how to retain good teachers

in the public school system. You will have 15 minutes to develop the ideas.

Step 2: When each team has completed the assignment, each is given two minutes to

present the two ideas. These ideas will be evaluated, and a winning team will be selected

based on the following criteria:

❏ The ideas are workable and affordable.

❏ The ideas are interesting, innovative, and unusual.

❏ The ideas have a good chance of making a difference if they are implemented.

Step 3: In addition to the team assignment, each team member is assigned to play three

team member roles during the discussion. A role assignment schedule is listed below.

Team members may select the roles they wish to play, or an instructor can assign the roles.

One purpose of this individual assignment is to give team members practice in playing

either task-facilitation roles or relationship-building roles in a team setting, so you should

take these assignments seriously. Remember, however, that you have only 15 minutes.

When your team has completed its task, each team member will rate the effectiveness of

every other team member in how well they played their roles and how much they helped

the team accomplish its task. You will have five minutes to complete the ratings.

T

EAM PERFORMANCE RATING

MEMBER (1) LOW–(10) HIGH

NAME ROLES PERFORMANCE FEEDBACK

1 Direction giving

Urging

Enforcing

2 Information seeking

Information giving

Elaborating

3 Monitoring

Reality testing

Summarizing

4 Process analyzing

Supporting

Confronting

5 Harmonizing

Tension relieving

Energizing

6 Developing

Consensus building

Empathizing

BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK CHAPTER 9 525

526 CHAPTER 9 BUILDING EFFECTIVE TEAMS AND TEAMWORK

Step 4: Each team member uses the form above to rate the performance of, and

provide feedback to, every other member of the team. In completing the form, make

sure you focus on how well each person performed his or her assigned roles. Identify at

least one thing you noticed about the performance of each team member so that you

can provide personal feedback to each one. Remember that the overall purpose of this

exercise is to give you practice in playing effective roles in teams and providing feedback

to team members. You are given five minutes for this rating task.

Step 5: When each team has completed its task, one representative from each team is

selected to form a judging team. This judging team evaluates the quality of the ideas

produced by each team. A winning team is announced as a result of their deliberations.

(Other class members will want to observe and rate the performance of this judging

team and its members as they make their selection.) The judging team will be given

10 minutes to select the winning team.

Step 6: Teams meet again so that personal feedback can be given. Each team member

takes a total of three minutes to give feedback to the other members of his or her team

based on the evaluation form above. A total of 20 minutes will be required to provide

this feedback.

Step 7: Hold a class discussion about what you observed regarding team members’ roles.

Especially, reflect on your own experience trying to play those roles and what seemed to be

most effective in facilitating task accomplishment and in building team cohesion.

The Problem Scenario

Almost to a person, the chief concern expressed by senior executives in most “old econ-

omy” firms is how to attract and retain managerial talent. With the economy expected

to grow at almost three times the growth of the job market, finding competent employ-

ees will be a continuing challenge for the next several years. The allure of dot.com

firms, high-growth companies, and high-risk–high-return ventures has created an

incredibly difficult environment for organizations whose chief competitive advantage is

intellectual capital and human talent. Headhunters, venture capitalists, and even firms’

customers are aggressively trying to lure away management talent any way they can. A

recent survey of Wall Street investment bankers revealed that more than half had been

approached by an Internet company. Armed with venture capital dollars and business

plans promising swift public offerings, it is easy to see why many are succeeding in

attracting managerial talent away from traditional companies. Compensation packages

in the seven figures are not unusual.

In this highly competitive environment where intellectual capital is at a premium,

consider the difficulty faced by not-for-profit organizations, local or state governments,

arts organizations, or educational institutions whose budgets are constrained far below

the high-priced world of the “new economy.” How will they compete for talent when

they cannot come close to the salaries of firms whose market capitalization exceeds the

GDP of many African countries?

In particular, the U.S. public education system has suffered tremendously in this

environment. Currently the United States spends more per child than any other coun-

try, and the costs of education are increasing far faster than the consumer price index.

However, it is well known that more than a quarter of public school students drop out

before high school graduation, and of those who remain, the percent passing proficiency

exams is woefully low—in some school districts, less than 10 percent. The average

tenure of public school teachers is less than seven years, and that number is dropping

rapidly as these knowledge workers can find positions elsewhere at triple and quadruple

their school salaries. Add to that the difficulties escalating in the classroom resulting