Wawro G. The Franco-Prussian War: The German Conquest of France in 1870-1871

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

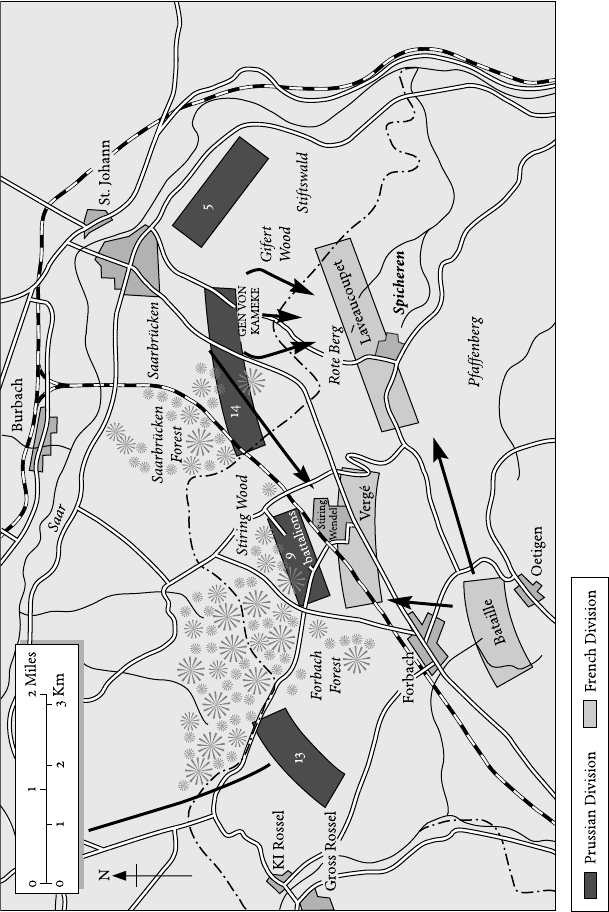

Map 5. The Battle of Spicheren

113

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

114 The Franco-Prussian War

position and awaited reinforcements, Frossard wondered just exactly how

many men he was facing. Every French counter-attack that formed above

Francois’s huddled companies was blown back by Kameke’s vigilant artillery.

Resourceful French gun teams that ventured down the height to shorten

their ranges and obviate the Krupp’s advantage were instantly brought un-

der counter-battery fire and chased away. By early afternoon five abandoned

French guns languished in no-man’s-land. They would be First Army’s first

trophies of the war if only Kameke could scale the Rote Berg.

Help was on the way. By mid-afternoon, Kameke’s 28th Brigade, com-

manded by General Wilhelm von Woyna, had relieved the exhausted remains

of Francois’s 74th Regiment at Stiring and fanned out along the wooded ridge

above the ironworks, taking the single brigade that Frossard had posted there

in a cross fire. As the battle of Spicheren sputtered back to the life with the

arrival of these fresh troops, Francois rose on the Rote Berg, drew his sword,

and led his men on to the bare red slope. Within seconds the general was dead,

ripped by five bullets. Many of his men met the same fate, the rest fell back

into the Gifert Wood. By 3:00 p.m., Kameke’s 14th Division was reeling; to

deal the knockout blow, General Laveaucoupet ordered his 40th Regiment

to counter-attack into Gifert Wood. They drove in with bayonets, pushing

Francois’s demoralized survivors before them. On Spicheren height, Frossard

permitted General Charles Verg

´

e to launch his second brigade at Woyna’s

troops in Stiring, knocking the freshly arrived Prussians almost all the way

back to Saarbr

¨

ucken. Had Frossard only strengthened these counter-attacks

and continued them, he might have dealt a stinging defeat to the Prussians.

But Frossard fully shared the French penchant for defensive tactics intro-

duced after K

¨

oniggr

¨

atz. Just as Laveaucoupet refused to leave the shelter of

Gifert Wood and pursue Francois’s survivors across the open ground toward

Saarbr

¨

ucken, so Frossard refused to leave Spicheren and the safety of his

position magnifique. Having expelled the Prussians, he sat down to wait.

“Battle is slaughter,” Clausewitz had written forty years earlier. If you

shy from it, “someone will come along with a sharp sword and hack off your

arms.”

70

This was a warning that Frossard should have heeded. As he reined

in his counter-attacks, the Prussians were sharpening their sword. Having

reached the outskirts of Saarbr

¨

ucken on the 6 August, Prince Friedrich Karl

and his leading units, Konstantin von Alvensleben’s III Corps and August

von Goeben’s VIII Corps, heard the sounds of battle from Spicheren and

immediately began shifting troops to the front. Battalions were sent by rail

along the Forbach line at half hour intervals; other units were sent on foot

along the arrow-straight Route Imp

´

eriale; Goeben’s 9th Hussars galloped

forward with two batteries of guns to help stem the rout below Stiring and

70 Carl von Clausewitz, On War, orig. 1832, Princeton, 1976,p.260.

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

115Wissembourg and Spicheren

the Gifert Wood. The contrast between the French and Prussian styles was

remarkable; whereas French generals exercised little initiative and seldom

strayed from fixed positions and lines of communication, Prussian generals

joined a battle at a moment’s notice, even if this meant moving with only

a fraction of their total strength and none of their supplies. Odd battalions

could be brigaded together, supplies and ammunition shared out. The main

thing was to increase numbers at the point of attack and put pressure on the

enemy.

General Alvensleben himself rode the rails to Saarbr

¨

ucken with a battalion

of the Prussian 12th Regiment. No sooner were his horses taken off than he

galloped forward to the battlefield and relieved Kameke of his blundering

command. Surveying the human wreckage of the day – lines of dead and

wounded in Prussian blue on the Rote Berg, the Gifert Wood and along the

Forbach railway – Alvensleben understood that the battle would have to be

begun all over again. He would have to work efficiently, for Bazaine had finally

agreed to lend Frossard Jean-Baptiste Montaudon’s division. If Montaudon

marched all out, he could still make Spicheren in time to intervene in the

battle.

71

While a brigade of the Prussian 5th Division retook the Gifert Wood,

nine more battalions, tumbling off their trains and march routes in no kind of

order from Alvensleben’s III Corps and Goeben’s VIII Corps, stretched the

attack along the entire edge of the height. Charles Verg

´

e’s division in Stiring

was finally dislodged and forced back on Forbach with heavy losses: 1,300

killed and wounded.

French facility with the rifle was demonstrated by Verg

´

e’s prodigious con-

sumption of ammunition that day, 146,000 cartridges. That this expenditure

by a single division represented one-third of the entire French war indus-

try’s daily production was at least as unsettling as the fact that fewer than

one round in seventy-five actually struck a Prussian. Clearly the problem of

fire control had still to be worked out.

72

Lieutenant Prosp

`

ere Coudriet of the

French 24th Regiment admired the discipline and cohesion of the Prussian

attacks under this withering if not always accurate French fire. Though the

Prussians ascending toward Spicheren were attacking into a semi-circle of

converging fire from two entire French regiments and a Chasseur battalion,

the Prussians plowed grimly ahead, their company columns preceded by long

lines of skirmishers, which used the ground well to evade French defensive

fire and pour in salvos of their own. Coudriet particularly admired the skill

with which the Prussian skirmish line – the only shield against the Chassepot –

was maintained. As Prussian fusiliers fell, they were swiftly replaced by or-

dinary infantry; 250-man companies would widen their intervals and sprint

71 J. B. Montaudon, Souvenirs Militaires, 2 vols., Paris, 1898–1900, vol. 2, pp. 4–7.

72 SHAT, Lb6, Metz, 10 Aug. 1870, Gen. Verg

´

e to Gen. Frossard. Lb4, Paris, 1 Aug. 1870, Gen.

Dejean to Marshal Leboeuf.

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

116 The Franco-Prussian War

forward to replace the casualties. By this rolling, firing advance, the Prussians

ground inexorably uphill, first through woods, then potato fields, then the

rusty gravel of the Rote Berg.

On the iron mountain, the ground was so steep that soil and grass would

not hold on the gravel slopes, and most of the Prussian wounds were to the

head, hands, or feet, the only body parts exposed to an entrenched enemy firing

straight down the vertical.

73

Against defensive fire like that, the Krupp guns

were an essential strut. At Spicheren, Prussian gun teams pushed to within

1,200 yards of the French trenches – a considerable feat on the steep slope –

and demolished them with explosive shells and shrapnel. Prussian shells burst

in twenty or thirty jagged shards; Prussian shrapnel scattered forty zinc balls

at bullet speed. This was hard to take in large doses. French senior officers

rushed in where the fighting was hottest, one remarking “wavering among the

troops”–“hesitation chez les soldats”–wherever the Prussian guns concen-

trated.

74

Coudriet of the 24th recalled seeing his regimental colonel torn apart

by shell fragments as he directed fire from behind a breastwork on the Rote

Berg. At last the French line began to give, pulled by the roughly one-third

of French effectives who were reservists, none of whom had been with their

regiments for more than a week when the Prussians struck.

75

By 6 o’clock –

when many of the Prussian units had been on their feet for thirteen hours –

Alvensleben had accumulated a substantial reserve of seven battalions, all from

his own corps. Although he had no idea where Montaudon’s division was, he

had to assume that French supports were in the vicinity.

To shatter what remained of Frossard’s corps before the arrival of re-

inforcements, General Alvensleben thrust this improvised reserve into the

flank of the French position, sending the troops up the Forbach Berg, a hump

of the Rote Berg that ran west toward Stiring. This brigade-strength for-

mation, steadily augmented by new arrivals, crested the ridge and staggered

into Laveaucoupet’s left flank. This combination of overlapping infantry at-

tacks and massed artillery barrages finally broke the French, who backed

off the Rote Berg toward Spicheren and then, as darkness fell at 9 o’clock,

yielded the entire plateau, flooding in opposite directions down the roads

to Sarreguemines and Forbach. The colonel of the French 63rd Regiment

voiced what would become a common complaint in the war: “Our men fired

their rifles all day to no apparent effect against an enemy who constantly in-

creased his numbers and turned our flanks.”

76

This, of course, was the Prussian

73 Shand, p. 22.

74 SHAT, Lb6, no date, no name, “Notes sur la part qu’a prise la 63 d’Infanterie

`

al’affaire de 6

Ao

ˆ

ut 1870.”

75 SHAT, Lb6, Bernay, 28 Nov. 1877, Lt. Coudriet., “24e Regt. De Ligne: Participation du

Regiment

`

a la journ

´

ee de Spickeren.”

76 SHAT, Lb6, no date, no name, “Notes sur la part qu’a prise la 63 d’Infanterie

`

al’affaire de 6

Ao

ˆ

ut 1870.”

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

117Wissembourg and Spicheren

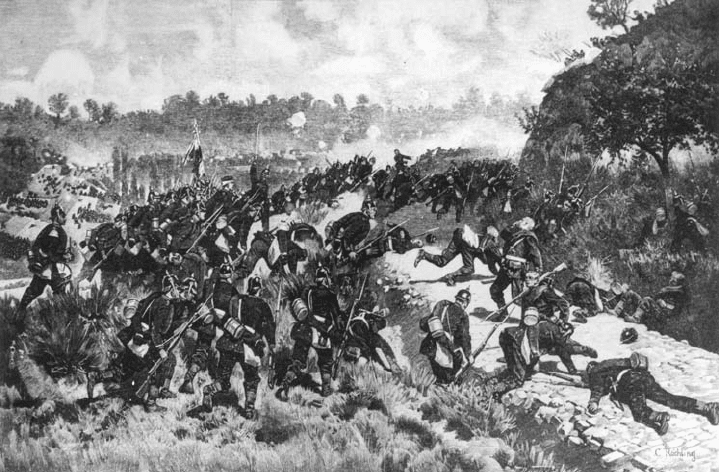

Fig. 5. Prussian infantry struggle on the Rote Berg

operational art in a nutshell: initiative, superior numbers at the chosen point,

flanking attacks, and encirclement. Driven from Stiring and the Rote Berg,

General Frossard briefly attempted to reform his position in Spicheren and

Forbach, but soon learned that the entire Prussian 13th Division, which had

crossed the Saar downstream at V

¨

olklingen, was marching into his unguarded

left flank and rear. The pocket or Kessel was closing, yet Frossard had no

reserves left to keep it open.

Giving up on the Saar, Frossard ordered a general retreat back to the line

of the Moselle. On both roads away from the plateau Frossard’s men collided

with General Montaudon’s march columns, which, having received no orders

from Bazaine until 3:30 p.m. and no information from Frossard until 4:00 p.m.,

were only now wearily arriving at the front after forced marches of eight to fif-

teen miles. General Armand de Castagny’s division, which, like Montaudon’s,

had belatedly “marched to the guns,” halted several kilometers south of For-

bach in darkness. The road was a bedlam of panicked troops and overturned

wagons. Frossard’s men –“starved, thirsty, dropping with fatigue”–were in

no mood to continue the fight.

77

Castagny, still striving to reach Spicheren,

recalled stopping one of Frossard’s generals and asking him “how long did it

77 SHAT, Lb6, Paris, 25 June 1872, Col. Gabrielle to War Minister.

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

118 The Franco-Prussian War

take your brigade to pass this road?” The general stared wildly at him: “Mais je

suis seul; j’ai perdu ma brigade”–“But I am alone; I have lost my brigade.”

78

Bazaine later called Spicheren a “sad, useless battle,” but he bore a large

measure of responsibility for the defeat. All four of his divisions could have

intervened to snatch victory from defeat; none of them did. Bazaine’s adver-

saries – Alvensleben and Goeben – exhibited the opposite tendency, feeding

battalions, squadrons, and batteries into the fight as quickly as they could be

made available. Bazaine, of course, needed to be more cautious.

79

His divisions

were spread forty miles from St. Avold to Bitche and he could not have known

that Spicheren was a major battle until very late in the day. To have reacted

earlier and sent large numbers of troops to Spicheren would have narrowed

his position and perhaps enabled the Prussians to sweep around Frossard

and him. He rebuffed Frossard’s first call for assistance at nine o’clock in the

morning, writing, “Our line is unfortunately very thin, and if this Prussian

movement is serious, it would be wiser to [withdraw].”

80

That rebuff was hard

to justify, for Frossard – himself in doubt as to the severity of the Prussian

attack – requested just two brigades, one of Montaudon’s for Spicheren and

one of Decaen’s for Forbach. Two brigades from two different corps would

hardly have compromised Bazaine’s position. Probably Bazaine’s failure had

more to do with a lack of acuity or just plain spite; the marshal did not like

Frossard, who was the imperial family’s favorite general.

Spicheren and Frossard’s efforts to excuse the defeat after the war led to

the creation of a “Dossier Frossard” in the French army archive, where senior

officers involved that day were invited to answer Frossard’s charges that he

had been abandoned by his colleagues. The gist of all the reports submitted is

that Frossard himself wavered too long between believing the Prussian attack

to be a minor affair and a serious battle. As late as 5:15 p.m. – as Alvensleben

was preparing his final push up to Spicheren and Zastrow’s 13th Division

was descending on Forbach – Frossard, deceived by yet another pause in

the action, wired Bazaine: “The fighting, which has been lively, has calmed

down . . . . I expect that I will remain master of this ground and will return

the Montaudon Division to you.” Bazaine, greatly relieved, was shocked to

receive the following telegram just two hours later: “Nous sommes tourn

´

ees”–

“we have been outflanked.”

81

The irresolution that Frossard displayed at

Spicheren simply could not be remedied under the conditions of nineteenth-

century warfare. A French division in the field needed two hours to prepare

itself for a march and many more hours to execute the march. Time was the

78 SHAT, Lb6, “Dossier Frossard,” Paris, 29 Nov. 1870, Gen. Castagny, “Reponse

`

a la brochure

du General Frossard en ce qui concerne la Division de Castagny pendant la journ

´

ee de

Forbach.” Montaudon, pp. 4–7.

79 Andlau, pp. 41, 50. Howard, p. 92.

80 Montaudon, pp. 4–7.

81 SHAT, Lb6, “Dossier Frossard,” Forbach, 6 Aug. 1870, Gen. Frossard to Marshal Bazaine.

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

119Wissembourg and Spicheren

critical element, yet Frossard the engineer let it slip away, perhaps, as one

colleague snidely noted, because Spicheren “was his apprenticeship in the

management of troops.”

82

Impressed by the effectiveness of French tactics on parts of the battle-

field, the Prussians marveled at the overall incompetence of their opera-

tions. On 7 August, Prince Friedrich Karl wrote Alvensleben and compared

Bazaine’s floundering at Spicheren with Benedek’sin1866: “As in 1866, the

French . . . let us prise apart several corps to strike at a soft, brittle mass,” in

this instance, General Charles Frossard’s II Corps. Writing to his mother two

days later, the Second Army commandant emphasized again the parallels with

the K

¨

oniggr

¨

atz campaign: “Everywhere this war is beginning like that of 1866,

crushing defeats of isolated corps and great demoralization. The woods about

here are full of enemy deserters. The position we took at Spicheren was in-

credibly strong.”

83

Indeed it was, and Prussia’s massive casualties at Spicheren

ought to have tempered all delighted comparisons with 1866. French marks-

manship and the Chassepot were killing Prussians at an unprecedented rate.

Whereas the Prussians had routinely killed or wounded four Austrians for

every Prussian casualty in 1866, they lost two men for every French casualty

at Spicheren. Nearly 5,000 Prussians were cut down in the battle, more than

half the number of Prussian killed and wounded at K

¨

oniggr

¨

atz, and this in a

relatively minor “encounter battle.”

Because of Steinmetz’s turn south and Kameke’s rashness, the Prussians

had absorbed brutal, wholly avoidable casualties. A witness who watched

King Wilhelm I tour the battlefield in an open carriage noted that he “ap-

peared stunned” by the unexpected carnage.

84

His only meager consolation

was the extent of French losses, surprising given the natural advantages of the

Spicheren position. Frossard lost 4,000 men, a sum that included 250 officers

and 2,500 prisoners seized in the rapid Prussian envelopment; the latter were

put to work burying the French and Prussian dead in mass graves all over the

field before being shipped across the Rhine to prison camps. When Frossard

reassembled his divisions in the following days, he found that they had lost

everything in the retreat: forty bridges, hundreds of tents, and food, clothing,

coffee, wine, and rum valued at 1 million francs.

Emperor Napoleon III’s cares were far heavier. The Prussians seemed to

be snipping off his army corps one after the other. It did seem eerily like 1866,

when the Prussians had isolated a succession of Austrian units and chewed

them up in frontier battles, draining Benedek of much needed strength in

82 SHAT, Lb6, “Dossier Frossard,” Paris, 29 Nov. 1870, Gen. Castagny, “Reponse

`

a la brochure

du General Frossard en ce qui concerne la Division de Castagny pendant la journ

´

ee de

Forbach.”

83 Foerster, vol. 2, pp. 145–7.

84 Friedrich Freudenthal, Von Stade bis Gravelotte, Bremen, 1898,p.106.

P1: GGE

CB563-04 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:16

120 The Franco-Prussian War

the days before K

¨

oniggr

¨

atz. Alarmed by the defeats at Wissembourg and

Spicheren, the emperor informed Bazaine that he would “pull in Marshal

MacMahon’s corps and concentrate the army in a more compact manner.”

85

With the Prussian armies spreading, as MacMahon worriedly put it, “like an

oil stain” between the French corps, Napoleon III and Leboeuf belatedly tried

to close the gaps. They were too late; MacMahon was about to be inundated.

85 SHAT, Lb 6, Metz, 6 August 1870, Marshal Leboeuf to Marshal Bazaine.

P1: IML/FFX P2: IML/FFX QC: IML/FFX T1:IML

CB563-05 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:19

5

Froeschwiller

After Wissembourg, General Abel Douay’s battered division – now com-

manded by General Jean Pell

´

e – had reeled away to the southwest in the di-

rection of Strasbourg. After pulling itself together on 5 August, Crown Prince

Friedrich Wilhelm’s Third Army moved off in Pell

´

e’s baggage-strewn wake.

Having lost contact with MacMahon, the Prussian crown prince wanted to

scour the ground east of the Vosges before turning into the mountains to join

the Prussian First and Second Armies on the other side.

1

To do this, he made

a difficult change of front southward: the Bavarian II Corps scrambled down

the road to Lembach on the right, the Prussian V Corps and XI Corps de-

scended on Woerth and Soultz in the center, and the W

¨

urttemberg and Baden

divisions – commanded by the Prussian General August von Werder – moved

up on the left at Aschbach.

The roads were difficult with ascending ranges of wooded hills that only

occasionally opened on to fields of corn or tobacco before the woods or vine-

yards closed in again. At first, the crown prince and his staff chief, General

Albrecht von Blumenthal, assumed that MacMahon was running for cover in

the fortress of Strasbourg. Late on the 5th, however, a Totenkopf hussar rode

through Woerth, noted barricades on the road to Froeschwiller, dismounted,

swam across the Sauer, had a long look at MacMahon’s sprawling position,

and galloped back to headquarters.

2

By late evening, the crown prince and

Blumenthal were fully apprised: MacMahon was not at Strasbourg; on the

contrary, he had scarcely moved from the positions he had held during the

battle of Wissembourg. He was still at Froeschwiller, like Spicheren, one of

the French army’s positions magnifiques. Blumenthal and Crown Prince

1 Frederick III, The War Diary of the Emperor Frederick III 1870–71, New York, 1927,

pp. 29–30.

2 Johannes Priese, Als Totenkopfhusar 1870–71, Berlin, 1936, pp. 30–8.

121

P1: IML/FFX P2: IML/FFX QC: IML/FFX T1:IML

CB563-05 CB563-Wawro-v3 May 24, 2003 7:19

122 The Franco-Prussian War

Friedrich Wilhelm were pleasantly surprised. Froeschwiller could be encircled

by a large army. That evening they began to plot a Kesselschlacht involving

the entire Third Army for 7 August.

3

Driven from Wissembourg on the 4th, MacMahon resolved to stand at

Froeschwiller, which he considered a strong position and a hub of France’s

eastern communications. If it fell, the Prussians would be able to seize con-

trol of the Bitche-Strasbourg railway as well as the principal roads pass-

ing through the Vosges. This, in turn, would isolate the French garrison at

Strasbourg and make it easier for the Germans to supply their large armies in

France.

4

The chief defect of Froeschwiller was its vulnerability to a flanking

attack. Though redoubtable against a frontal assault, Froeschwiller was easily

turned from the south by a large army, and large numbers of troops were

something that the Germans had in abundance in 1870. Against MacMahon’s

corps of 50,000, Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm had an army of 100,000 de-

scending on Froeschwiller in three great columns. MacMahon ought to have

abandoned the position and withdrawn through the Vosges, but he needed

time to collect Pell

´

e’s division and still hoped to combine with other French

troops in the area to counter-attack the Prussians and recover the ground

lost at Wissembourg. Early on 6 August he ordered General Pierre de Failly,

commander of the French V Corps, to make his 30,000 troops ready for one

of two eventualities: either an attack on the Prussian Third Army as it passed

through the Vosges defiles or a bold envelopment of the Prussian crown prince

if he dawdled at Wissembourg.

5

Given the numerical odds against MacMahon,

this was admirable pluck, but misguided. The Prussians rarely dawdled, and

were far too thorough to turn into the Vosges without first making sure of

MacMahon.

Froeschwiller was an imposing obstacle with clear fields of fire in all di-

rections. The village perched above the Sauer river and overlooked the impor-

tant road junction of Woerth, where the plain of Alsace began to rise into the

wooded Vosges. Like Spicheren, it wrung every advantage from the Chassepot

rifle, because Froeschwiller and its neighboring village of Elsasshausen sat at

the heart of a semicircular position on the right bank of the Sauer, flanked by

Eberbach on the right and Langensoultzbach on the left. The four villages were

linked by a lateral road and easily reinforced. Prussian attacks into this bowl

of fire would be impeded by the Sauer, as well as the vines and hop plantations

crowded onto the slopes below the French position. On a pre-war staff ride,

Marshal MacMahon had paused to study the position and declared: “One day

3 Munich, Bayerisches Kriegsarchiv (BKA), HS 849, Capt. Girl, “Einige Erinnerungen,”

p. 43.

4 Vincennes, Service Historique de l’Arm

´

ee de Terre (SHAT), Lb 6, Saverne, 7 Aug. 1870,

Marshal MacMahon to Napoleon III.

5 SHAT, Lb 6, Camp de Froeschwiller, 6 Aug. 1870, Marshal MacMahon to General de Failly.