Water Power and Dam Construction. Issue July 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 41

SEDIMENTATION

A

N environmentally-friendly dewatering system is being

launched after a successful pilot project which helped to

keep Britain’s canal network open to trafc. The Sedi-

lter system has been created as a complete solution to

dewatering engineering projects. Designed by environmental waste

management rm Aardvark EM, the system is manufactured by

DRM Industrial Fabrics, which specialises in performance ltra-

tion through design. Its creators believe the system will be of great

benet to dam and hydropower plant operations involved in silt

extraction projects and the creation, stabilisation and restoration

of watercourses.

Sedi-lters have been designed to dewater large volumes of water-

based slurries generated from maintenance operations on lakes and

waterways and from industrial processes. They can also be used to

create articial weirs, berms and reefs in watercourses, and for ero-

sion control in the marine environment.

Mark Clayton, managing director of Aardvark, has been heavily

involved in the development of Sedi-lter. “Sedi-lter is of great help

in terms of extracting silt as well as playing a key role in stabilising

watercourses by using lled dewatering bags in the water to help sta-

bilise banks,” he says. “There is really no limit when it comes to the

depth of water Sedi-lter can work in. We are looking at a project in

the Thames Estuary, near Canary Wharf, where they would operate

at a depth of 8m with no problems.”

Sedi-filters have already provided Midlands-based Blue Boar

Contracts – which has a national contract with British Waterways to

dredge canals to a navigable depth – with an environmentally-friendly

solution to the problem of containing and dewatering sediment in

conned areas and holding and treating contaminated sediment.

In a pilot project, the company used Sedi-lter’s bespoke dewater-

ing bags to contain and dewater sediment taken from a 3km stretch

of the Birmingham and Worcester Canal in the heart of Birmingham

city. After successful results during the three-month pilot project, the

company is now using Sedi-lter’s dewatering system to deal with

most of its contaminated sediment.

The dewatering system has a strong environmental benet and can

be effective in a wide variety of dewatering and engineering applica-

tions, says the developers. The main gain is the removal of water from

sediment, transforming it into a drier state, which helps handling and

enables the sediment to be disposed of to landll or used elsewhere.

Blue Boar director Simon Potter is impressed with the way the system

has helped his company’s work: “The use of the Sedi-lter system

means that we don’t have to add anything to the contaminated sedi-

ment to treat it before it is disposed of. That means we don’t have to

have a special licence to deal with the waste and we are not increasing

the weight of the sludge. We can dry it out using the Sedi-lter system,

so it can be accepted to landll and, because the water is extracted,

we are actually reducing the amount we are taking away. This means

lower transport costs and less weight at the landll weighbridge.”

DEWATERING SOLUTION

Sedi-lter dewatering systems have been created to tackle the environ-

mental problems associated with excavating and storing wet slurry,

sludges and sediments. Made from high-quality geotextiles, Sedi-lter

is designed to effectively capture solid materials without the use of

excessive or specialist machinery. It removes excess water from wet

wastes, such as sludges, dredged silts and washwaters, through a pas-

sive ltration process. Solids are held within the tube, as the water

passes through the fabric and ows back to its original source, sur-

rounding ground or another collection point. The result is a signi-

cant reduction in the volume of solid waste that has to be handled

and dealt with – as up to 90% of the water is removed.

If the solid waste is contaminated, like the canal sediment, then the

wet material can be placed in the Sedi-lter and the water extracted. The

Sedi-lter can be used to contain contaminated sediment whilst treat-

ment is applied, as dewatering itself does not decontaminate sediment.

The bag is made of a close weave textile, which aids the dewater-

ing process. The lters are engineered to withstand pressure at the

base, which allows for stacking. They can be made to almost any size

depending on application. The standard size is 7m wide x 33m long

– with a volume of approximately 250m

3

.

Filling is via pumping, the dorsal openings at the top centre of the

bag combine an entry port and sleeve, this allows a pipe to be inserted

and clamped inside the sleeve. Filling is controlled through a mani-

fold/valve system, each tube is lled and allowed to dewater. Once

dewatered, the Sedi-lter is lled again and the process is repeated,

until the dewatered sediment volume is approximately 80%.

A wide variety of treatments can be applied to the slurry during and

after pumping. Air lines can be run through and clamped in place and

microbes added, as well as mixing and agitation.

www.sedi-lter.co.uk

IWP& DC

A new dewatering system offers the dams

and hydropower industry a solution to

sedimentation problems

All systems go for Sedi-filter

42 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

COMMENT

O

VER the past 58 years, the author has been fortunate

to work on both large and small hydro developments,

and managed to keep detailed statistics on project engi-

neering services. The author found that there was a

vast difference in the project documentation required by a private

utility, as compared with that demanded by a public utility. Also,

there was a signicant difference in how the design and construc-

tion work was undertaken for small as compared with large hydro

developments. After many years, a distinct pattern in man-hours

was discerned, as will be discussed in this paper.

PROJECT ENGINEERING MAN-HOURS

After completion of a feasibility report, one of the rst questions asked

by the hydro project owner; is how much will the detailed engineering

work cost? This is very difcult for the consultant to estimate with any

degree of accuracy. It was found to depend on several factors:

r How much documentation will be required by the owner?

r How will equipment bids be analyzed and what justication will be

required on contractor selection?

r How will orders for the equipment be placed?

r Will the owner question all invoices for the engineering services?

The answers to these questions will directly affect the man-hours

required to undertake the design and project management, resulting

in two types of engineering services offered to owners – (1) a docu-

mented design service, and (2) a non-documented design service.

A documented design would entail the production of:

r A ‘Design Criteria report’: A document showing the criteria to be

used in design of each structure, forwarded to the client for perusal

by the client’s Review Board, prior to starting detailed designs.

r A ‘Design Transmittal’: A document showing how each structure was

designed, for permanent retention in the client’s project les, to be

used whenever there are repairs or modications to the structure.

r A ‘Contract Award document’: A report on how the contractor was

selected, to include all specications and correspondence with the

selected contractor prior to award.

r A ‘Project Completion Report’: This document would include

copies (on CD) of all project drawings and photographs, and copies

of all progress reports issued during construction.

r A ‘Project Operating Manual’.

Such detailed engineering services would normally be required for

all major hydro developments, by large utilities and for international

bank-nanced projects.

A non-documented design is one where a client or contractor is

willing to entrust the engineering services to a consultant, without

requiring any documentation on the design or construction, and

the only documentation provided would be: a copy of all project

drawings; and an operating manual. This standard of work would

be equivalent to the design work undertaken by a consultant for the

general contractor on a design-build project, or that required for a

small hydro development of less than about 50MW capacity.

From 1952 until 1990, the author worked for Montreal

Engineering (Monenco), a consultant who provided design, construc-

tion and operating services to many associated hydro utilities. These

utilities did not require any detailed project documentation; hence the

author was able to accumulate data for non-documented engineer-

ing services, where most of the contracts for construction, turbine

and generator were negotiated with reliable known contractors and

manufacturers. Bids for other equipment were solicited from, at most,

three manufacturers. Specications were concise. For example, all the

technical specications for civil works and mechanical equipment at

the 356MW Brazeau project were contained in a 2.5cm three-ring

binder. About 1960, Monenco began providing services to ‘outside

clients’ who required more formalized engineering with full documen-

tation of the work, and required all contracts to be open for bidding

by pre-qualied contractors. As a result, specications became more

detailed and contractual conditions more complex. This provided an

opportunity to obtain data on documented designs. The results are

shown in Table 1, where the data was accumulated over 32 years

between 1954 and 1986 for 8 non-documented projects and for nine

documented projects.

One of the rst questions owners ask is ‘what will be the cost of engineering services’.

This paper discusses the effect of documented/non-documented designs on project

engineering costs, based on detailed man-hour data obtained from 17 hydro projects

ranging in size from the 6.4MW Maggoty development in Jamaica, to the 2304MW

La Grande 3 development in Quebec. By J L Gordon, P.Eng

Hydro project engineering costs

Project man-hour statistics

Project Head

(m)

Capacity

(MW)

MW/h

0.3

Man-hours

Non-documented projects

1. Maggoty (Jamaica) 88 6.1 1.6 10,850

2. Snare Falls (Canada) 19 6.7 2.8 28,900

3. Umtru (India) 58 11.7 3.5 16,300

4. Rattling Brook (Canada) 94 12.5 3.2 20,220

5. Taltson (Canada) 30 18.3 6.6 22,176

6. Bearspaw (Canada) 15 15.2 6.7 17,460

7. Bighorn (Canada) 75 110 30.1 86,400

8. Brazeau plant (Canada) 118 336 91.2 97,410

Brazeau pump (Canada) 7.6 20

Documented projects

9. Charlot River (Canada) 29 11 4.0 45,100

10. Dadin Kowa (Nigeria) 28 34 12.5 66,000

11. Maskekeya Oya (Sri Lanka) 578 100 14.8 97,674

12. Andekaleka (Madagascar) 214 112 22.4 135,000

13. Cat Arm (Canada) 381 136 22.9 167,00

14. Wreck Cove (Canada) 350 200 34.5 131,200

15. Bayano (Panama) 50 300 92.8 261,000

16. Jebba (Nigeria) 28 560 206.1 352,00

17. La Grande (Canada) 79 2304 621.1 630,000

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 43

COMMENT

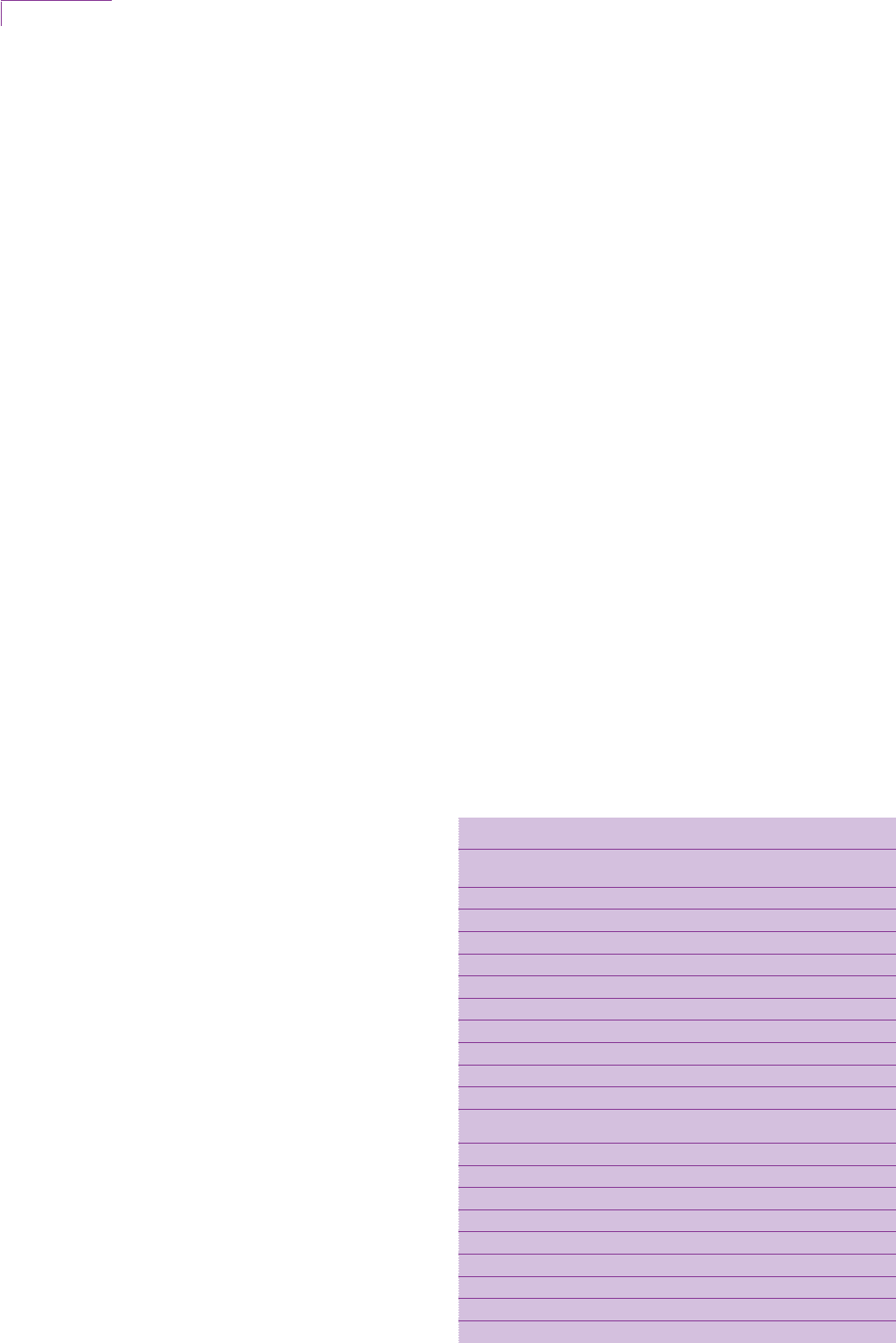

Analyzing the data, the author found that there is a factor of about 2.5

between a ‘documented’ as compared with a ‘non-documented’ design

and managed project, as shown in Figure 1. There are two distinct lines

on the gure. The lower line (B) represents the man-hours for a ‘non-

documented’ design, and the upper line (A) represents a documented

design. Both lines can be expressed by the following equation

Man-hours = k (MW/h

0.3

)

0.54

(1)

Where: h = rated net turbine head in meters; MW = installed capacity

in megawatts; k = a factor with a value = 8,300 for a non-documented

design, and = 21,000 for a documented design.

In other words, a documented project requires over 2.5 times the

effort expended on a non-documented project. This is very important,

and a factor which must be taken into account by any owner contem-

plating awarding a contract for engineering services.

There are some projects on the chart which do not t the data.

These can be explained by:

r 2 – Snare Falls. The dam site on this project was changed at the last

minute, when the owner decided that the project capacity should

be increased by about 50%. This was accomplished by moving the

dam site downstream to the next set of rapids, after all contracts

had been issued for tender. This required a complete re-design of

the project layout.

r 4 – Rattling Brook. This project proceeded with only a pre-fea-

sibility study, requiring extensive additional studies on dam and

spillway locations.

r 10 – Dadin Kowa. This project was terminated when the client ran

out of money, and still requires completion of the powerhouse and

installation of spillway gates.

r 13 – Cat Arm. During the design engineering work, the owner

decided to add about six utility engineers to the consultant’s electri-

cal design team to learn how to design the automatic controls, with

the intent to retrot the design onto older powerplants. Also, there

were signicant changes to the project concept when detailed design

work commenced, which included use of a U-shaped weir spillway

instead of a gated spillway, impulse units instead of Francis units,

and elimination of the surge tank.

r 7 – Bighorn. This project was undertaken after a change in the man-

agement at the utility. The new management required all contracts

to be tendered instead of being negotiated, adding substantially to

the weight of both the technical and contractual conditions in speci-

cations, and requiring more formal documentation of the work.

It is remarkable how consistent the data appears to be. All of

the projects were undertaken by Monenco, with the exception

of Wreck Cove, engineered by SNC, with Monenco acting as the

owner’s consultant, and LG3, engineered by SNC in association

with Cartier Engineering, a subsidiary of Monenco. Also, two

of the projects, at Maskeliya Oya and Bayano, were designed

from project ofces in Colombo and Panama, staffed with a few

Canadian engineers, with all the other engineers and draftsmen

being provided by the utility client.

The chart is based on data from projects undertaken before the intro-

duction of computerized drafting, (CAD) which one would expect to

reduce drafting time. The author has tried to determine whether CAD

has had a signicant effect on man-hours, to no avail, since consult-

ants are naturally reluctant to divulge such data. However, the author

is of the opinion that CAD and other similar programs have instead

increased drafting time, since now it is very easy to produce more draw-

ings, and to produce three-dimensional images of powerplant interiors

and even individual concrete pours, both of the latter requiring signi-

cant additional input data. The added engineering simplies construc-

tion work, but increases engineering man-hours.

Also, the work was undertaken before personal computers became

available. Again, one would expect that computers would reduce

the engineering effort. However, based on observing the extent and

detail of recent specications for large developments, the author is

of the opinion that computers have indeed facilitated, but have also

increased engineering man-hours.

HYDRO SPECIFICATIONS FOR DOCUMENTED AND

NON-DOCUMENTED PROJECTS

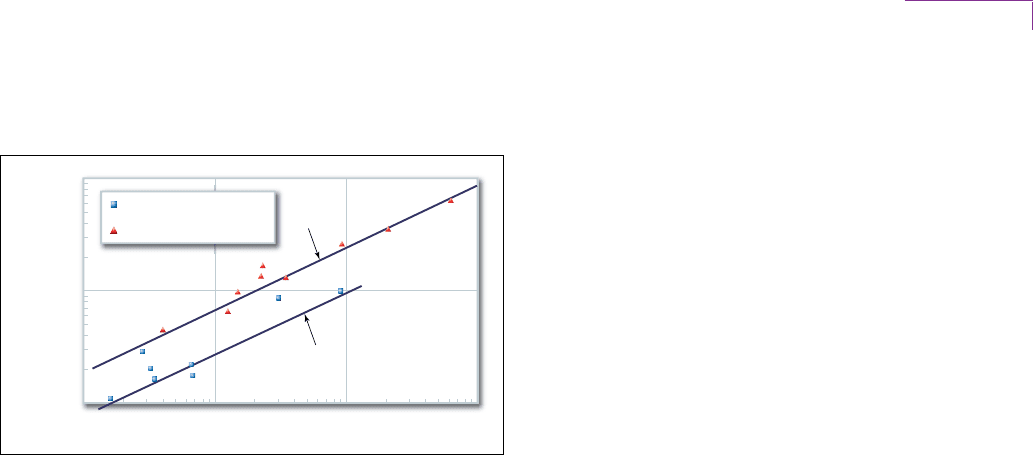

This raises the issue of the effort required to produce specications and

contract documents. A perfect illustration of the difference is shown in

Figure 2, where the large 3-ring binder contains the technical specica-

tions only for the civil works on a medium-sized documented 200MW

hydro project, and the small document on the left contains the civil

specications, the geological report, contractual conditions and the

environmental guidelines for the civil works contract at a small low-

head non-documented 600kW hydro development. The right-hand

document was produced by a large consultant in Vancouver, and the

other document by a small consultant in Halifax.

The author is of the opinion that it is very difcult for a large hydro

consultant to produce a short specication. Large consultants have

the ability to retain specialists in many disciplines, and consequently

have few ‘generalists’ able to work on a variety of structures and

equipment. For example, the mechanical department in a large con-

sultant’s ofce could have an engineer specializing in powerhouse

cranes, another in gantry and gate hoists, another in powerhouse

pumps, compressors and piping, and another in turbines. All would

be required to contribute towards an equipment specication, and

the result would be a document requiring considerable co-ordination

between the specialists. On the other hand, a small consultant would

have perhaps only one mechanical engineer, and this person would

be required to produce the specications for all the mechanical equip-

ment. The resulting document would be more concise than that pro-

duced by the large consultant.

DOCUMENTED PROJECT DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT

To illustrate the difference in project management between a docu-

mented and non-documented work, the data for the large document-

ed Jebba hydro project is presented. Jebba is located on the Niger

River in Nigeria, and includes a large shiplock. It was commissioned

in 1984. It has an installed capacity of 560MW at 27.6m head from

6 vertical axis Kaplan turbines. The completed project can be clearly

viewed on Google Earth at 9-08-20N, 4-47-27E.

Major project quantities at Jebba included:

r Earth excavation: 1,230,000m

3

.

r Rock excavation: 3,270,000m

3

.

r Earth ll: 2,120,000m

3

.

r Rock ll and rip-rap: 2,930,000m

3

.

r Spillway, lock, weir concrete: 241,000m

3

.

r Powerhouse concrete: 245,000m

3

.

Total cost of the project was over $1B in 1980 US$. Time

spent on engineering and project management was 386,000

1,000.000

100,000

10,000

Manhours

110100 1,000

MW/h 0.3

>

Non-documented projects

Documented projects

2

4

10

7

13

A

B

Figure 1: Design engineering man-hours

44 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

COMMENT

man-hours, of which 27% (104,000mh) was on project

management and construction supervision. The project was fully

documented, which required the production of both “design

criteria” documents and “design transmittal reports” for each of the

nine major structures. Based on detailed statistics maintained through-

out project execution, the project management group supervised the

production and distribution of:

r 23 contract documents, with a total of 2478 pages of technical

specications, plus contractual conditions.

r 364 tender drawings.

r 1406 construction drawings.

r 7335 manufacturer’s drawings received for review by the design

engineers.

r 131 construction reports, with a total of 12,569 pages.

The production of drawings had to be kept ahead of the contractors’

requirements, and peaked at 512 approved for construction draw-

ings issued in the month of February 1980. Of course, it was not

possible to engineer such a large number of drawings in one month;

they were produced over the previous year when design staff peaked

at 72 individuals. The general civil work contract was signed at the

end of January 1978, and in March seven copies of 198 drawings

were packed in a large box and sent by air freight to the contrac-

tors head ofce, knowing that it was essential to keep ahead of the

contractors requirements for detailed construction drawings.

Cost control was maintained by an accounting team at site, and

was complicated by having to use four currencies – US dollars, Italian

Lira, Japanese Yen and German Marks. During construction, it was

difcult to determine the current total cost due to the constant change

in the relative value of the currencies. The project was completed

in 1984, after six years of construction. Management staff averaged

nine persons over this period, and peaked at 13.

NON-DOCUMENTED PROJECT DESIGN AND MANAGEMENT

A non-documented design will not require such a large project man-

agement team as at Jebba. Another factor to be taken into account

is the recent use of water-to-wire equipment contracts, wherein the

contractor undertakes a major proportion of the powerhouse elec-

trical and mechanical design work. This means that the consultant

can often dispense with the services of electrical and mechanical

engineers, further reducing the cost of project execution. Another

factor is the introduction of high speed internet services over the last

decade. This has allowed many engineers and technicians to work

from home, working within informal groups to provide design serv-

ices for small hydro projects. There are several such groups, where a

hydrologist, civil engineer, geotechnical engineer and a CAD drafts-

man produce all drawings, and all working from home.

An early demonstration of this concept was provided at Ragged

Chute, where the addition of a small 6.3MW, 13m head development

at an existing dam in Canada was undertaken in 1992. The work was

supervised by the owner (a retired contractor) from a rented nearby

cottage, a civil engineer and draftsman with no hydro experience

were engaged to undertake powerhouse and intake design, another

to design the penstock, a senior hydro consultant provided advice,

and costs were audited by a hydro engineer appointed by the bank

providing the nancing. A geotechnical engineer was engaged to pro-

vide advice on slope stability during excavation work. Ragged Chute

is located at 47-16-35N, 79-40-19W, and is clearly visible on Google

Earth. Total staff involved were; three engineers (owner + civil +

draftsman) for about 18 months, plus another four engineers very

much part-time. There was a water-to-wire contract for the equip-

ment, and a general contractor undertook the construction and also

designed the plant plumbing, heating, lighting and ventilation sys-

tems. There was no documentation other than an operating manual

provided by the water-to-wire contractor, and a set of drawings.

CONCLUSIONS

The rst decision facing a hydro owner is how much documentation

of the project execution work will be necessary? For large projects,

documentation is required. There is a grey zone between about

25MW and 100MW where documentation is optional. However, for

small hydro work, of less than about 50MW, documentation should

be kept to a bare minimum.

Recently, the author has seen specications issued by hydro utilities

for engineering services. They include extensive requirements for very

detailed project documentation, even for small hydro projects, and

the author is of the opinion that such specications have been issued

without understanding the effect on engineering costs. It is hoped that

this paper will help to clarify such issues.

Jim Gordon is an independent hydropower consultant,

and can be reached at – jim-gordon@sympatico.ca

IWP& DC

Small – large hydro specifications compared

Recruitment

opportunities

Recruitment

opportunities

To advertise in this section

please contact:

Diane Stanbury:

Tel: +44 (0)20 8269 7854

or

email:

dianestanbury@globaltrademedia.com

recruit.indd 1 23/7/10 12:11:41

Hydro SE is engaged in the construction and implementation

of Hydro Electric Power Plants in the Balkans and

eastern Europe.

We are seeking a

top level engineer

to be part of a leading

team and to become instrumental in decision making process,

managing sub-contractors and handling all critical aspects of

project implementation.

The prospect candidate must have:

1

MSC in Hydro Engineering.

2

10 years or more of experience in construction

of hydro power plants.

3

Experience in managing multiple and complex projects.

4

Excellent commercial understanding.

5

Willingness for substantial traveling.

6

Fluent English spoken and written is a must.

Additional languages - advantage.

The position holder will be required to relocate to Zagreb.

Excellent compensation package for the right candidate.

Please send your CV and references in English to:

Hydroengineer1@gmail.com

INTERNATIONAL EMPLOYMENT

OPPORTUNITIES

SMEC International (Pty) Ltd (www.smec.com) is

a leading engineering consulting firm with over 4000

employees providing multidisciplinary engineering

services including in Dams, Hydropower, and Power

engineering. SMEC has an established network of

34 major offices throughout Australia, Africa, Asia,

The Middle East and the Pacific.

SMEC is currently expanding its Nairobi (Kenya)

Office which supports SMEC’s Dam, Hydropower

and Power projects throughout Africa. SMEC is

currently filling the following positions in its Africa

Division:

8/-(#!1,%#/#0'%,

8/6"/-*-%'01

8/+#0'%,,%',##/

8/*#!1/-#!&,'!*,%',##/

8/6"/-#!&,'!*,%',##/

8/#,'-/#-*-%'01#-1#!&,'!*,%',##/

(Dams)

8/*#!1/'!**,1,%',##/

8/-++2,'!1'-,-,1/-*,%',##/

8/-4#/-20##0'%,,%',##/

8//,0+'00'-,,%',##/

8/2 11'-,,%',##/

For more information about positions, please visit

SMEC’s website.

SMEC offers excellent employment conditions.

Professionals with at least ten years of relevant

#5.#/'#,!#./#$#/ *64'1.#/'#,!#',2 &/,

Africa are invited to send their detailed curriculum

vitae and a cover letter to proc.ken@smec.com or

submit their application via the “Career” section of our

website www.smec.com prior to

21 August 2010.

SMEC also accepts CVs of other experienced

engineers interested in working in Africa.

SMEC:Layout 1 21/7/10 15:07 Page 1

RECRUITMENT

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 45

PROFESSIONAL DIRECTORY

46 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

CLASSIFIED

www.waterpowermagazine.com

MORE THAN 100 YEARS OF HYDROPOWER ENGINEERING

AND CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT EXPERIENCE

260 Dams and 60 Hydropower Plants (15,000 MW)

built in 70 countries

Water resources and hydroelectric development

•Public and private developers

•BOT and EPC projects

•New projects, upgrading and rehabilitation

•Sustainable development

with water transfer, hydropower, pumping stations

and dams.

COYNE ET BELLIER

9, allée des Barbanniers

92632 GENNEVILLIERS CEDEX - FRANCE

Tel : +33 1 41 85 03 69

Fax: +33 1 41 85 03 74

e.mail: commercial@coyne-et-bellier.fr

website: www.coyne-et-bellier.fr

COYNE ET BELLIER

Bureau d’Ingénieurs Conseils

www.coyne-et-bellier.fr

Over 40 years experience in Dams.

CFRD Specialist Design and Construction

●

Dam Safety Inspection

●

Construction Supervision

●

Instrumentation

●

RCC Dam Inspection

●

Panel Expert Works

Av. Giovanni Gronchi, 5445 sala 172,

Sao Paulo – Brazil

ZIP Code – 05724-003

Phone: +55-11-3744.8951

Fax: +55-11-3743.4256

Email: bayardo.materon@terra.com.br

ba_mater@yahoo.com.br

Lahmeyer International GmbH

Friedberger Strasse 173 · D-61118 Bad Vilbel, Germany

Tel.: +49 (6101) 55-1164 · Fax: +49 (6101) 55-1715

E-Mail: bernd.metzger@lahmeyer.de · http://www.lahmeyer.de

Your Partner for

Water Resources and

Hydroelectric Development

All Services for Complete Solutions

• from concept to completion and operation

• from projects to complex systems

• from local to multinational schemes

• for public and private developers

• hydropower

transmission and high

voltage systems

power economics

power management

consulting

www.nor consult.com

Multidisciplinary consultancy

services through all project cycles

dams and waterways

turbines/pumps and

generators

water resources

environmental and

social safeguards

AF-Colenco Ltd

Täfernstrasse 26 • CH-5405 Baden/Switzerland

Phone +41 (0)56 483 12 12 • Fax +41 (0)56 483 17 99

colenco-info@afconsult.com • http://www.af-colenco.com

Consulting / Engineering and EPC Services for:

• Hydropower Plants

• Dams and Reservoirs

• Hydraulic Structures

• Hydraulic Steel Structures

• Geotechnics and Foundations

• Electrical / Mechanical Equipment

Construction and

refurbishment of small

and medium hydro

power plants.

.

t

u

r

n

k

e

y

/

E

P

C p

l

a

n

t

s

.

d

e

s

i

g

n

&

e

n

g

i

n

e

e

r

i

n

g

.

t

u

r

b

i

n

e

s

.

f

eas

i

bi

l

i

ty

s

t

udi

e

s

.

o

p

e

r

a

t

i

o

n

s

e

r

v

i

c

e

s

.

financ

i

ng

www.hydropol.cz

# (47) 67 53 15 06 in Norway

# (55) 11 3722 0889 in Brazil

E-mail: nickrbarton@hotmail.com

Website: http//www.qtbm.com

3

3

5

5

y

y

e

e

a

a

r

r

s

s

e

e

x

x

p

p

e

e

r

r

i

i

e

e

n

n

c

c

e

e

f

f

r

r

o

o

m

m

m

m

o

o

r

r

e

e

t

t

h

h

a

a

n

n

3

3

0

0

c

c

o

o

u

u

n

n

t

t

r

r

i

i

e

e

s

s

PROFESSIONAL DIRECTORY

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 47

CLASSIFIED

www.waterpowermagazine.com

Yolsu Engineering Services Ltd. Co.

Hürriyet Caddesi No:135 Dikmen, 06450 Ankara,TURKEY

Tel: +90 312 480 06 01 (pbx) Fax: +90 312 483 31 35

www.yolsu.com.tr info@yolsu.com.tr

Prefeasibilty, Feasibility,

Final & Detail Design,

Consulting Services:

• Basin development

• Dams and hydropower plants

• Irrigation and drainage

• Water supply and sewerage

• River engineering

• Highways and railways

Successful projects in

Hydropower and Water

Management

F

or further information please contact

h

p.energy@poyry.com and visit www.poyry.com

Stellba Hydro AG Stellba Hydro GmbH & Co KG

Langgas 2 Badenbergstrasse 30

CH-5244 Birrhard D-89520 Heidenheim

Switzerland Germany

Telefon +41 (0)56 201 45 20 Telefon +49 (0)7321 96 92 0

Telefax +41 (0)56 201 45 21 Telefax +49 (0)7321 6 20 73

Internet www.stellba-hydro.ch Internet www.stellba.de

E-Mail info@stellba-hydro.ch E-Mail info@stellba.de

721

www.rizzoassoc.com

WATER RESOURCES POWER GENERATION

MINING TUNNELS

TECBARRAGEM

SLIPFORM

Phone/Fax: + 5511 51812527

tecbarragem@tecbarragem.com.br

Website: www.tecbarragem.com.br

• Faster Constructive System for Civil Works

• Specialists in Hydroelectric and Dam Projects

• Qualified Projectists, Engineers and Technicians

• Special Formworks and Slipforms

To advertise in the Professional Directory or

World Marketplace section, or for more

information contact Diane Stanbury.

tel: +44 (0)20 8269 7854

or email:

dianestanbury@globaltrademedia.com

Copy deadline for August 2010 issue

is 3 August 2010

I N T E R N A T I O N A L

& DAM CONSTRUCTION

Water Power

www.waterpowermagazine.com

The classified section in Water Power & Dam

Construction is a well established and popular

section with the magazine’s combined print and

digital circulation of 16,000. Commonly known

as where “the buyer meets the seller”.

Industry Showcases

The industry showcase section is made up

of eighth page adverts (95x65mm) with a

maximum of eight key suppliers to a page. It

is a n ideal section to promote products

and services, raise brand awareness and

shout about company successes. Showcase

adverts ar e also an ideal way to promot e

product literature and generate interest.

Recommended duration:

minimum 3 months

Recruitment

The ideal way to promote a company vacancy

and reach experienced professionals looking

for the next opportunity t o advance their

career in the hydro power & dam construction

industries.

For more information, please contact

Diane Stanbury

Telephone: +44 (0)20 8269 7854

or email:

dianestanbury@globaltrademedia.com

WORLD MARKETPLACE

48 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

CLASSIFIED

www.waterpowermagazine.com

CYLINDERS

CRANES GATES

• Custom Design Hydraulic Cylinders

•

Servomotors

•

Piston Accumulators'

• Hydraulic Power Units

• Control Panels

www.doucehydro.com

Douce Hydro FRANCE, USA and GERMANY

Tel France: + 33 / 3 22 74 31 08 ; E-mail: afleroy@doucehydro.com

Tel USA: + 1 / 586 566 4725 ; E-mail: fvandenbulke@doucehydro.com

Tel Germany: + 49 / 177 398 37 78 ; E-mail : ublase-henke@doucehydro.com

BEARINGS

PAN

®

bronzes

and

PAN

®

-GF

self-lubricating bearings

Since 1931

- Superior quality with

• Highest wear resistance

• Low maintenance

• Or maintenance free

-

Extended operating life

PAN-Metallgesellschaft

P.O. Box 102436 • D-68024 Mannheim / Germany

Phone: + 49 621 42 303-0 • Fax: + 49 621 42 303-33

k

ontakt@pan-metall.com • www.pan-metall.com

BEARING OIL COOLERS

HEXECO, Inc. ... a Heat Exchanger Engineering Co.

Tel: +1 (920) 361-3440 • Fax: +1 (920) 361-4554

E-Mail: info.wpd@hexeco.com • Web: www.hexeco.com

OIL COOLERS

For

THRUST and

GUIDE

BEARINGS

CONCRETE COOLING

FILTRATION EQUIPMENT

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM

CIVIL ENGINEERING:

U Þ`iÀÃ] «ÜiÀ ÕÌÃ >` VÌÀÃ

vÀ `> }>ÌiÃ] ëÜ>Þ }>ÌiÃ]

Ì>i }>ÌiÃ] ÃÕVi }>ÌiÃ

U }iiÀ}] ÃÌ>>Ì >` V

ÃÃ} v V«iÌi Þ`À>ÕV

>` iiVÌÀV ÃÞÃÌià vÀ `> }>Ìi

«iÀ>Ì Õ« Ì >ÕÌ>ÌV ÀiÃiÀÛÀ

ÌÀ} >` VÌÀ ,®

www.montanhydraulik.com

Providing water control solutions through thoughtful engineering,

innov ative design, attention to detail and outstanding customer

service. Contact us for inflatable water control gates and rubber

d

ams.

PO Box 668, Fort Collins, CO 80522 USA

Tel: 970-568-9844

www.obermeyerhydro.com

HYDRO CASTINGS

• Water turbine components

• Castings from 100 kg to 30 tons

• Latest CAD-CAM capabilities

• Certified Quality Assurance ISO 9001

• Environmental Management System ISO14001

Your contact: Mr. Timo Norvasto, Sales Manager

Lokomo Steel Foundry

Tel: +358 204 84 4222

Fax: +358 204 84 4233

Email: timo.norvasto@metso.com

Web: www.metsofoundries.com

CONCRETE COOLING

• COLD & ICE WATERPLANTS

• FLAKE ICE PLANTS

• ICE DELIVERY & WEIGHING SYSTEMS

• ICE STORAGES

KTI-Plersch Kältetechnik GmbH

Carl-Otto-Weg 14/2

88481 Balzheim

Germany

Tel:/Phone: +49 - 7347 - 95 72 - 0

Fax: +49 - 7347 - 95 72 - 22

Email: ice@kti-plersch.com

Website: www.kti-plersch.com

WORLD MARKETPLACE

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 49

CLASSIFIED

www.waterpowermagazine.com

HYDROMECHANICAL

EQUIPMENT

HYDRO POWER

PLANT EQUIPMENT

HYDRO POWER

PLANT EQUIPMENT

ANDRITZ HYDRO GmbH

Penzinger Strasse 76, A-1141 Vienna, Austria

Phone: +43 (1) 89100-0, Fax: +43 (1) 8946046

contact-hydro@andritz.com • www.andritz.com

Your Partner

for renewable and clean energy

We focus on the best solution – from water to wire.

Voith Hydro Holding GmbH & Co. KG

Alexanderstrasse 11

89522 Heidenheim/Germany

www.voithhydro.com

A Voith and Siemens Company

! Water power plant equipment

(electrical and mechanical)

! Pumps

! Governors

! Automation

! Modernization of existing power plants

! Hydro power services

! Ocean energies

INSTRUMENTATION

(DAM MONITORING)

Vikas Kothari: Executive Director Tel: 91 11 29565552 TO 55

Om Metals Infraprojects Ltd. Fax: 91 11 29565551

4th Floor, NBCC Plaza, Mobile: 91 98110 68101

Tower III, Sector 5, Email: vikas@ommetals.com

Pushp Vihar, info@ommetals.com

Saket, New Delhi, 110 017, INDIA Web: www.ommetals.com

Turnkey EPC contracts for:

•Radial Gates •Trash Racks & TRCM

•

Vertical Gates •Gantry Cranes & EOT

•Penstocks •Mechanical/ Hydraulic Hoists

•Stoplogs •Draft Tubes

Turnkey EPC contracts for:

•Radial Gates •Trash Racks & TRCM

•

Vertical Gates •Gantry Cranes & EOT

•

Penstocks •Mechanical/ Hydraulic Hoists

•Stoplogs •Draft Tubes

Om Metals

Reliable and innovative solutions utilizing

over 156 years continuos hydro-electric

experience.

F

ully customised supply of turbines,

generators, controls, switchgear &

a

ssociated plant up to around 20MW,

including a micro hydro range of turbines.

Japan: Gilbert Gilkes & Gordon Ltd

h-yamamo@rf6.so-net.ne.jp

North America:

Vancouver Island Technology Park

2103 - 4464 Markham Street

Victoria BC V8Z 7X8

b.sellars@gilkes.com

t: 250-483-3883

UK: Gilbert Gilkes & Gordon Ltd,

Canal head North, Kendal,

C

umbria LA9 7BZ

[ M

hydro@gilkes.com

! World wide referenced water to wire General Contractor

! Turbines and Generators

! Electromechanical Equipment

! Switchgears

! Control Protection Monitoring and SCADA Systems

! Balance of the Plant

! Turn key projects

! Rehabilitation

S.T.E. S.p.a. - Via Sorio, 120 - 35141, PADOVA(Italy)

tel. +39 049 2963900 - fax. +39 049 2963901

Email: ste@ste-energy.com Web: www.ste-energy.com

ISO 9001 CERTIFIED

Geokon, Incorporated manufactures a full range

of geotechnical instrumentation suitable for

monitoring dams. Geokon instrumentation employs

vibrating wire technology that provides measurable

advantages and proven long-term stability.

The World Leader in

V

ibrating Wire Technology

T

M

Geokon, Incorporated

48 Spencer Street

Lebanon, New Hampshire

03766

•

USA

Dam Monitoring Instrumentation

1

•

603

•

448

•

1562

1

•

603

•

448

•

3216

info@geokon.com

www.geokon.com

Dam Safety Instrumentation • Fiber Optic and

Vibrating Wire Technologies • In-Situ Testing

and Turn-Key Solutions

• Piezometers

• Pressure Cells

• Extensometers

• Crackmeters

• Inclinometers

• Tiltmeters

1-877-ROCTEST

info@roctest.com

• www.roctest.com

33.1.64.06.40.80

info@telemac.fr

• www.telemac.fr

WORLD MARKETPLACE

50 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

CLASSIFIED

www.waterpowermagazine.com

SMALL HYDROELECTRIC

POWER SETS

SMALL HYDROELECTRIC

POWER SETS

Turbines up to 20 MW

Alternators up to 22 MVA

Governors

Switchboards

79261 Gutach /Germany

Tel . + 49 7 6 85 9 1 06 - 0 · Fa x : - 1 0

www.wkv-ag.com

Water-to-Wire Solutions Made in Germany

Turbine & Alternator Manufacture

W

TRASHRACK RAKES

MICRO/SMALL

HYDROELECTRIC POWER SETS

Turbines up to 20 MW

Alternators up to 22 MVA

Governors

Switchboards

79261 Gutach /Germany

Tel . + 49 7 6 85 9 1 06 - 0 · Fa x : - 1 0

www.wkv-ag.com

Water-to-Wire Solutions Made in Germany

Turbine & Alternator Manufacture

W

INSTRUMENTATION

(GEOTECHNICAL)

Partial Discharge?

www.pdix.com

PARTIAL DISCHARGE DETECTION

+

43 - 7234 - 83 902