Water Power and Dam Construction. Issue July 2010

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Make your project a success...

... by optimising your hydropower investments

With our worldwide expertise and proven track record we will help you to fi nd the best solution.

... by getting solutions quickly

You will deal with one project manager to support you. No more time-consuming meetings with

different partners. We have everything inhouse. Just a single source of competence.

... by using our global network

More than 300 hydropower specialists will give you a competitive advantage.

Pöyry is a global consulting and engineering company with 7,000 experts in 50 countries.

For further information please contact hp.energy@poyry.com and visit our website www.poyry.com

www.poyry.com

12 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

SMALL HYDRO

A

SIMPLIFIED history of hydropower in the New England

area begins hundreds of years ago as small mill owners

harnessed the energy available in falling water and convert-

ed it to usable mechanical power. Later, this energy was

converted to electricity and by 1940 approximately 40% of the US’

electrical demand was met through hydroelectric generation. With

the increased use of inexpensive fossil fuels, the majority of these

smaller hydropower facilities were eventually left to ruin. Today in

a seemingly endless quest for renewable energy, we have returned to

our roots and the hydropower boom has once again begun.

There are many challenges associated with small hydropower devel-

opment. For those involved in the industry it will be no surprise to see

regulation discussed rst. However, there are other important challeng-

es such as acquiring the initial capital investment, overcoming market

instabilities, and for now let’s say nding some ‘Yankee Ingenuity’.

REGULATIONS

With few exceptions, new hydropower is heavily regulated under

the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The process of

obtaining permission to construct, maintain and operate a hydroelec-

tric plant through the means of a licence or exemption document is

typically a lengthy and expensive process. Pursuant to 18 CFR 4.38

and 5.1 (d), and 16.8, an applicant seeking an exemption or licence

must consult with relevant federal, state, and interstate resource agen-

cies, Indian tribes, and non-governmental agencies.

Comments and suggestions by these stakeholders can be in refer-

ence to sh and wildlife mitigations but also extend to historic con-

cerns, recreational issues, and the aesthetic impact of the project on

the surrounding area. Furthermore, there are provisions that licences

for hydroelectric projects must include conditions to protect, mitigate

damages to, and enhance sh and wildlife resources.

Specic project conditions required for a hydro plant are deter-

mined through a stakeholder consultation process, which typically

includes a series of costly studies. The results may not only indicate

measures to reduce impacts during construction but also permanent

operations measures that may reduce the overall annual energy gen-

eration of the project.

In general the small hydropower community in New England is

a tight group of hard working folks who are environmentally con-

scious. They support fair-minded measures which assist them in con-

structing and operating their sites in a manner that is environmentally

Siblings Celeste and William Fay have a long history and unique

perspective in the small hydro industry. Here they share their

experiences and explain how the endless quest for renewable

energy is prompting a renaissance for small hydro in the US

Small hydro renaissance

Prospecting potential micro-hydro sites in New Hampshire,

Site pictured is a 100 hp turbine directly connected to an air compressor

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 13

SMALL HYDRO

friendly. The heart of the issue is very simple. Why does a proposed

50kW hydroelectric project at an existing dam site, with minimal

additional environmental consequences, go through the same lengthy

and expensive process as a new 5MW site? Why isn’t there a stream-

lined process for non controversial projects or low impact projects?

To be fair, FERC itself held a workshop in December 2009 on

small non federal HEPs where these same questions were asked. The

cumulative results were summarised in a FERC press release from

April 2010 which stated that the commission is working to ease the

regulatory burden of small hydro regulations through developing new

online resources, creating simplied licence/exemption application

templates and improving coordination with resource agencies.

FINANCE ISSUES

Acquiring the initial capital investment and overcoming market

instabilities to be able to develop small hydropower are intertwined

issues. Sometimes it is possible to obtain a xed power sales con-

tract. However, more likely than not, the energy generated is sold to

a larger electric company based upon ISO New England open market

rates. In other words, the value of the energy is based upon supply

and demand, which is subject to wild uctuation and can be difcult

to predict.

French River Land Co (FRLC) in Ware, Massachusetts owns

the Tannery Pond HEP that sells energy to National Grid for open

market rates. FRLC receives a spreadsheet on a monthly basis that

details, on an hourly basis, the amount of energy generated and the

corresponding rate. It is not unusual to see the value of energy reach

a high of US$300/MWh but a low of US$0MWh. As an example, for

the ISO New England central/western Massachusetts zonal area, the

average value of energy for this year to date (June 2010) is around

US$48/MWh. However, having a potential value of US$0/MWh does

not typically make a nancial institution feel comfortable lending a

developer the funding required to get the project off the ground.

Renewable energy certicates (RECs) have assisted in this area.

Typically, a xed value contract for the RECs is signed for a year or

more. However the average value in the New England area is only

around US$20-30/MWh for nancing purposes.

YANKEE INGENUITY

Now we come to the Yankee Ingenuity. Large hydropower produc-

ers have the luxury of additional monetary resources, which means

that there is more room for outsourcing of engineering and construc-

tion services. The small hydro producer must be more careful in this

respect, be able to evaluate available resources and make them work

to their advantage. If we look at sites that are making an average

annual energy generation between 100MWh/yr and 2000MWh/yr

and assume an average energy value of US$50/MWh with an addi-

tional US$30/MWh in RECs, the average annual value of the site’s

energy is approximately US$16,000 and US$160,000.

Some costs such as environmental studies, engineering, and con-

struction materials are more or less xed; therefore, others must be

minimised to the extent possible for a small project to be nancially

viable. Depending on how one looks at it, the opportunity or chal-

lenge here is in planning and designing a site to use existing structures

and equipment.

In New England, a new dam is very difcult to construct and really

is not a necessary requirement. With tools such as Google Earth and

GIS data, the ability to nd existing, unused dams has been greatly

enhanced. Many old mill sites still have extensive civil works such as

penstocks, powerhouses or tailrace structures. Of course, it is rare

to nd these structures in a state such that they do not require some

rehabilitation. Yet often, a simple economic analysis will show that

using these structures will drastically increase the economic viability

of small hydro.

Additionally, many hydroelectric facilities today are generating

using equipment that is almost 100 years old and with a surprisingly

high efciency. Whether it is the equipment found on-site or procured

from somewhere else, used equipment is not something that the small

hydro developer should overlook even if it requires rehabilitation. A

small hydro site does not necessarily require all the bells and whistles

and will likely not be economically successful if anything other than

the bare minimum is installed.

For example, a colleague of ours uses a simple mechanism consist-

ing of a rope, pulley, telephone repeater, and weighted paint bucket as

a regulating mechanism for the governor on his turbine and it works

great. This approach is not for everyone but if the average annual

generation of a site is below a certain threshold, this kind of plan of

attack is critical to success. It should be noted that the primary goals

of some developers is not to generate an income stream. Companies

may be looking to meet green goals or to preserve their long-term

sustainability by offsetting their electrical demand with renewable

energy. These folks will still nd benet in using Yankee Ingenuity

but it may not be quite as critical.

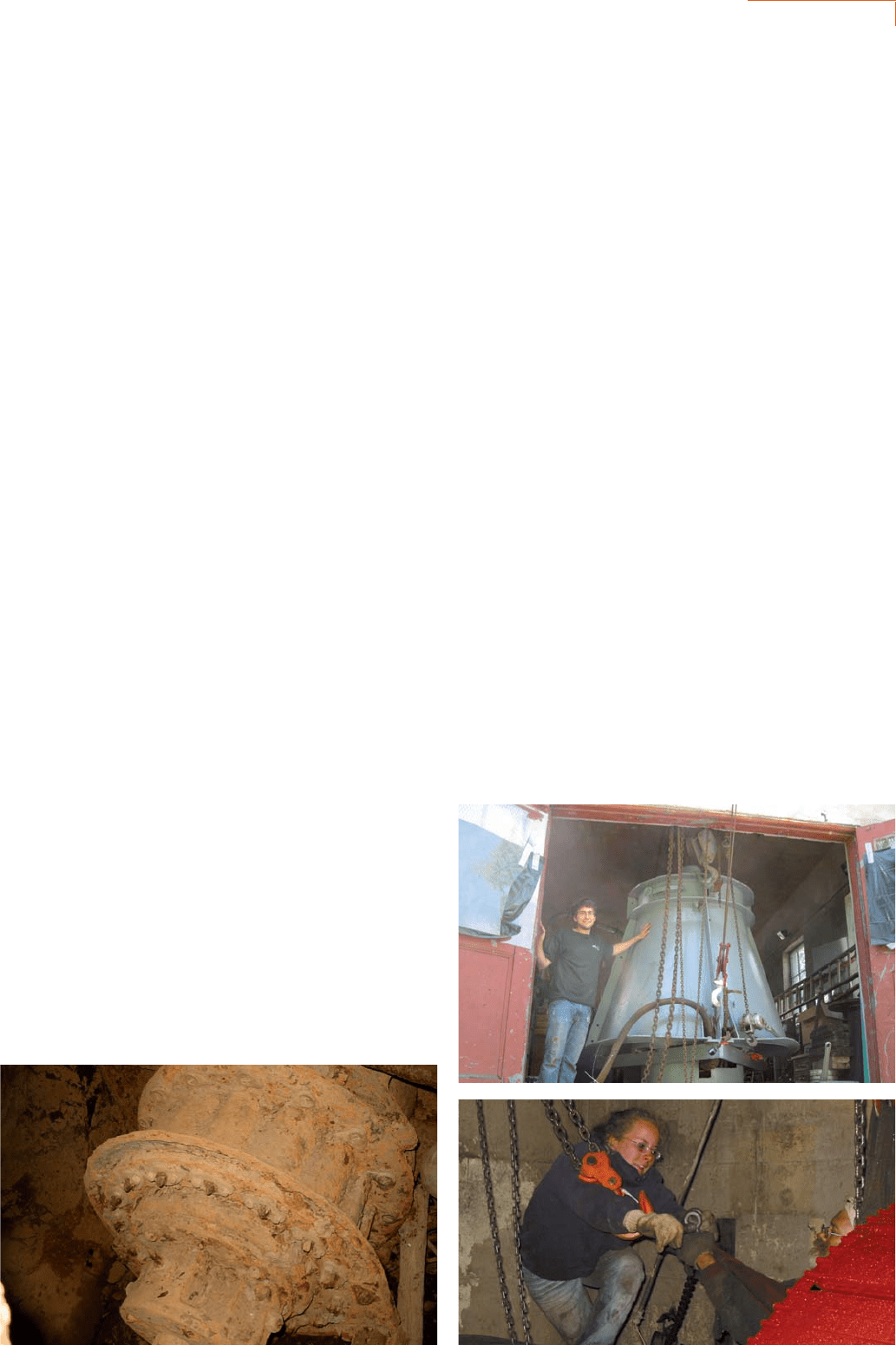

RIght: Will moving the Tannery Pond turbine; Below: 18 Inch Rodney Hunt Type

60 being rehabilitated for the Tannery Pond HEP Grant; Below right: Celeste rigging

a 640kW generator into a rehabilitated HEP

14 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

SMALL HYDRO

REPOWERING SITES

This is the business model that we have built as a result of our limited

economic resources and our abundance of hydropower knowledge.

We became involved in hydropower at a young age because we grew

up in and around hydroelectric power plants. When we were chil-

dren, our father would bring us to various HEPs and we would do

small tasks to assist with both engineering and hands-on site reha-

bilitation tasks. As we gained more of a grasp on exactly what it was

that we were doing, we gained more interest and enthusiasm for the

hydroelectric eld.

Towards the end of our high school careers, our father and his

partner had acquired larger power plants in the 1200kW to 4000kW

range. The Tannery Pond hydropower station in Winchendon,

Massachusetts was originally licensed for 189kW and it was quickly

becoming obsolete in comparison to a 4000kW project. We wanted

to become more involved in hydropower and eventually took over

French River Land Company and the Tannery Pond HEP. The

Tannery Pond facility had not produced electricity prior to us taking

over the project. The station posed many challenges but we perse-

vered and were able to repower the site.

When we took over the Tannery Pond project, the station had a

FERC exception, an interconnection, two non-operational turbine-

generating units and all the necessary civil works such as the dam,

intake, trash racks, and powerhouse. The rst unit was a Rodney

Hunt 96cm diameter runner, type 80 Francis turbine, coupled

through a 200hp Paramax 90 degree gearbox, to a 150hp-1800rpm

induction generator, which had the potential to produce 80kW on the

3.4m of available head. The second unit was originally a homemade

turbine that had poor design characteristics. The turbine could not

operate efciently and was removed.

In 2009, FRLC obtained a US$461,000 grant through the

Massachusetts Technology Collaborative to install two remanufactured

Francis turbine-generating sets and computer controls in the Tannery

Pond plant. This work will be completed by the end of 2010.

Around the same time, we removed a Leroy-Somners, Hydrolec,

semi-kaplan turbine from a mill in New Hampshire. The turbine, hel-

ical gearbox, and generator are located within an oil-pressurised bulb,

in a anged pipe section, mounted on a penstock. The unit was thor-

oughly dilapidated and required a full rehabilitation. Unfortunately,

parts and mechanical specications for the unit were not available.

It took almost a year of part-time work to rebuild the unit with new

roller bearings, gears, and various other parts. The rehabilitation was

completed in 2005 and the site successfully produced electricity.

SEARCHING FOR SMALL HYDRO

During the same period we were looking for other small hydroelec-

tric projects. Our limited nancial resources restricted us. However,

we located a potential project on the Squam river in Ashland, New

Hampshire, which we were able to purchase through the graces of

owner nancing in 2005. The Ashland hydroelectric project is an

84kW FERC licensed project constructed in 1984. The station had

originally been under a generous power sales contract from the

1980s that set the value of energy at about US$20/MWh; but this

had expired previous to our purchase.

We were fortunate though to negotiate a power and sales con-

tract with the Ashland Light Department, which included provisions

for the department to conduct limited operations. The station has a

Leroy Somners, Hydrolec tube turbine, rated at 84kW on 5.5m of net

head. The unit had been struck by lightning, disassembled, and left in

a eld for almost ve years.

Our 18-month part-time rehabilitation of the turbine included the

replacement of just about every mechanical and electrical component

in the unit. A fair amount of guesswork was involved since no parts,

plans, or specications were available from the original equipment

manufacturer. But with the use of our father’s machine shop, we were

able to repair the unit and it began generation in November of 2007.

ENJOYING THE CHALLENGE

As our skills and knowledge expanded, our involvement in the

engineering portion of hydroelectric power plants also expanded.

We both enjoy the challenge and joy of sharing our hydroelec-

tric knowledge with others by nding economical solutions for

the development of small hydropower throughout New England.

There is once again a small hydro renaissance occurring not only

in New England but also throughout the county and it is an excit-

ing time to be involved in the industry.

Celeste N. Fay, GZA Geo-Environmental, Email:

cfay0570@yahoo.com and William D. B. Fay, French

River Land Company. Email: wfay@frenchriverland.com

www.frenchriverland.com

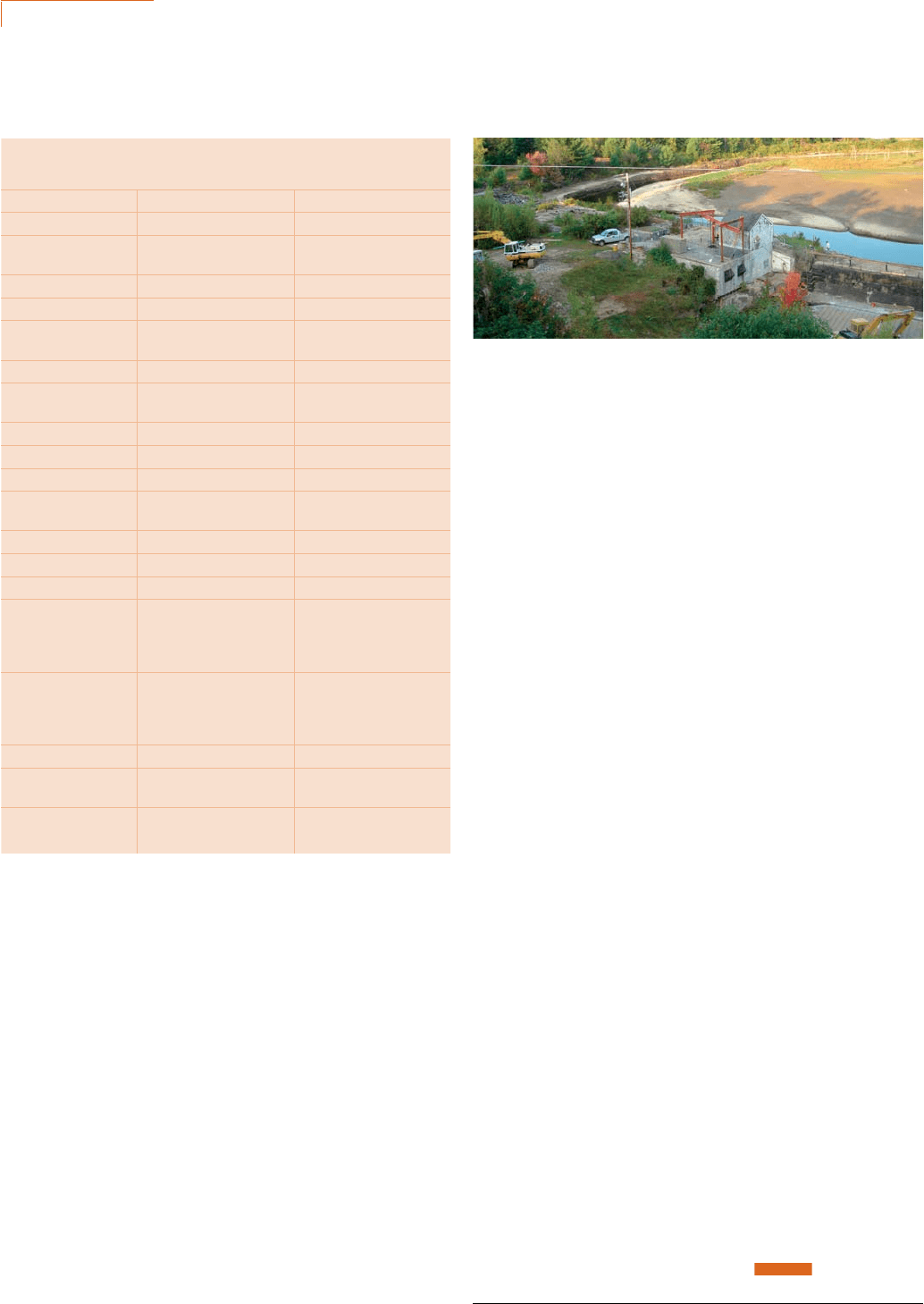

View of Ashland hydroelectric project

IWP& DC

Technical data on the FRLC projects

Tannery Pond Ashland

Dam type Gravity Dam Gravity Dam

Dam material Laid eldstones Concrete capped granite

blocks

Dam length 125ft 80ft

Dam height 6ft 12ft

Spillway type Overow weir w/

ashboards

Overow weir w/

ashboards

Year constructed 1913 1925

Impoundment surface

area

8 acres 12 acres

River Millers Squam

Drainage area 49 square miles 67 square miles

Average flow 92 cfs 88 cfs

Average annual

minimum flow

4 cfs 15cfs

Bypass reach length 760 ft 320 ft

Minimum bypass flow 21 cfs 32 cfs

Installed capacity 189kW 84kW

Turbine type Unit 1 – 38” Rodney Hunt

Type 80, Unit 2 – 48”

Leroy Somners Semi-

Kaplan

Unit 1 – 36” Leroy

Somners Semi-Kaplan

Generator type Unit 1 – 1800 rpm

induction generator, Unit

2 – 900rpm induction

generator

Unit 1 – 1800 rpm

induction generator

Hydraulic capacity 230 cfs 79 cfs

Average annual

generation

510,000kWh/yr 420,000kWh/yr

Regulatory status FERC exemption from

licensing

FERC exemption from

licensing

Turbine & A l t e r na t o r Manufacture

Turbines up to 20 MW

Alternators up to 22 MVA

Governors

Switchboards

Am Stollen 13

79261 Gutach/Germany

Tel. + 49 7685 9106 - 0

Fax: + 49 7685 9106 - 10

www.wkv-ag.com

Water-to-Wire Solutions Made in Germany

WKV_86x134_E_4c_RZ 07.07.2010 12:37 Uhr Seite 1

#*3+$(.

+,4'2")-%#

#!#

#!#

"

*(&$-),($&#'

*(&$-),($&#'

*.##'!' -*#+"&',+(

#%(*+#!'

(*('!# )*,#('

*,#%(*(*#2(',%

1)( ('+,*-,#('

(*%/#'*,(*

0)(*,*

-&$&!)$%!'&! %-'%&$ )!$ %" #'&+

-*"$ $!!($"$!&%-"$&!$ !)!)

-!$)&(&%-"$ !$ ,&!

- %&$&'".%$(%

..

!

Liquid Energy – Solid Engineering

gugler 31/3/09 14:10 Page 1

16 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

SMALL HYDRO

F

OR many families around the world, access to modern

energy is a pipedream. People are forced to cook on open

res that ll their homes with toxic smoke and as the light

fades each evening so too does the possibility of adults

working into the evening, children studying, and families cooking

safely in well-lit, clean homes.

This lack of access to energy traps people in a constant cycle of

poverty that they unable to break free from.

Over 1.6B people – almost one third of the world’s population – have

no electricity. In Africa four out of ve families live without electricity,

according to international development charity, Practical Action.

CHANGING LIVES

Practical Action believes that the right idea, however small, can change

lives. The charity works with some of the world’s poorest women,

men and children helping to alleviate poverty in the developing world

through the innovative use of technology and facilitating access to

energy for poor communities through a variety of means, enabling

them to lift themselves out of poverty and change their lives.

The charity was founded in 1966 by radical economist E.F.

Schumacher who strongly believed in using small scale, low cost

and appropriate ideas to change people’s lives and that ethos still

rings true today. Specically, Practical Action is working to imple-

ment small scale renewable energy schemes in rural communities

that aren’t linked to the national grid. It is enabling them to be

involved in the construction and management of renewable projects

and provide a sustainable source of energy for the rst time that will

safeguard future generations.

MICRO HYDRO SYSTEMS

Practical Action has developed small scale micro hydro schemes with

communities in Peru, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Kenya and Zimbabwe as

well as in Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Bolivia, Mozambique

and Malawi as part of the charity’s extension work from its country

ofces. These systems, which are designed to operate for a minimum

of 25 years, are usually run-of-river systems.

A system with a capacity of 6kW is big enough to drive a mill and

provide electrical lighting for up to 20 families.

As well as driving a generator to provide electricity, micro hydro is

also used in these areas to supply power to remote villages via recharge-

able batteries that can be used for lighting and to play small radios and

power TV sets. Lighting is one of the basic needs of poor people and

they can have much better and safer lighting at a lower cost through the

use of this technology by replacing candles and kerosene lamps.

Practical Action is different to other development charities in that it

uses a participatory approach in all of the work that it carries out in

the communities. Engineers from the charity will enter a community,

assess its needs and resources and also determine the most appropriate

technology for the particular conditions. When micro hydro is decided

upon as the best option, decisions will be made following calculations

to determine the most appropriate materials to use and how much the

scheme is going to cost based on the number of families it needs to

Bringing water power to the poor

Development charity Practical Action believes that the right idea, no matter how small,

can change lives. Here Teodoro Sanchez shows how micro hydro schemes are helping to

transform lives around the world

Civil engineering for a micro hydro system in Bocatoma, Peru

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 17

SMALL HYDRO

serve, the potential growth of the community and their possible eco-

nomic development. It’s also necessary to assess the capacity of the

country as to whether national industry can produce equipment and

components that will t the needs of the project or is already produc-

ing them. If it is the case that presently there is not such a capacity,

Practical Action provides technology and technical assistance to enable

local manufacturers to produce the equipment required.

Once a technology is decided upon and manufactured, the tech-

nology is implemented and then the training begins. Members of

the local community will be selected in a participatory manner and

trained to manage the operation and maintenance of a micro hydro

system and the community must decide how they will pay for its

upkeep – repairs, replacement components etc. A tariff scheme will be

devised by the community with Practical Action’s help, ensuring that

the scheme will be sustainable and last for many years to come.

CASE STUDIES

Chipendeke, Zimbabwe

One such project has recently been implemented in Chipendeke,

Zimbabwe, situated along the Wengezi river. This micro hydro scheme

provides 25kW of electrical power which serves almost 130 families.

This quantity of energy provides enough electricity for domestic needs

such as lighting, as well as providing power to a health centre, school

and numerous small businesses being run by community members.

The cost of this scheme ran to Euros 87,000 (US$108,000) and

85% of the cost was part funded by the EU. The other 15% was

funded by the community contributing with labour and local materi-

als. With the initial investment taken care of, the community is only

left responsible for paying for management and maintenance of the

system which consists of a small payment each month.

Chorro Blanco, Peru

Chorro Blanco is an isolated community in the Cajamarca region

of the Peruvian highlands. The cost of rural electrication through

the national grid would probably have meant that Chorro Blanco

remained without modern energy for many generations. The supply

of micro hydropower provided electricity for 60 rural families and 90

families from neighbouring villages for the rst time in their lives. The

scheme provided electricity for domestic and public lighting, small

businesses and battery charging.

The scheme comprises the intake weir, conveyance ditch, settling

basin and forebay tank, penstock and anchors, powerhouse and dis-

charge channel. The local community is also making a sizeable con-

tribution to the manpower requirements of the project, transporting

materials to the site and assisting with labour.

This scheme generates 20kW of electrical power; it uses a locally made

Pelton turbine, a penstock made of PVC and an electronic load control-

ler. The electricity is transported from the powerhouse to the village using

1.6km mid-tension lines and set-up and step-down transformers.

CHALLENGES

Working with poor communities, and sourcing materials, within a

developing country presents a number of social and cultural obstacles

to Practical Action staff when implementing micro hydro schemes.

The poverty of the families involved leads to issues with funding par-

ticularly when there is no outside investment from local governments

or bodies, and many families can struggle with budgeting for mainte-

nance payments for their systems.

In rural communities that use energy sources such as kerosene or

biomass for their needs, fuel is typically purchased in small quanti-

ties. Families have never needed to budget and commit to a regular

monthly payment which can be a difcult concept to adapt to but is

essential to ensure the sustainability of the schemes. To resolve this,

extensive training is undertaken within the communities to explain

the costs and implications of sustaining a micro hydro system.

THE FUTURE

Practical Action works continually with staff based in its country ofces

identifying opportunities and communities that can benet from small

scale renewable energy schemes. The charity works to engage with local

governments and decision makers to source funding and continue its

work. Practical Action adopts a ‘bottom-up’ approach where local gov-

ernments are encouraged to learn from the technologies implemented,

adopt them and replicate them across the country once they can see the

difference they are making to people’s lives.

GET INVOLVED

Practical Action is currently campaigning for ‘energy for all’ by 2030.

Modern energy transforms lives; improves health and education and

lifts people out of poverty. The charity will be developing a group of

energy ambassadors towards the end of the year, to nd out more

email campaigns@practicalaction.org.uk .

Teodoro Sanchez is an Energy Technology and Policy

Adviser at Practical Action.

Email: Teodoro.sanchez@practicalaction.org.uk.

For more information about Practical Action’s work in

renewable energy around the world please visit

www.practicalaction.org.uk.

Children use electric light provided by the micro hydro system to study after dark A woman sits by the forebay tank for a new micro-hydro system, Peru

IWP& DC

18 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

SMALL HYDRO

T

APPING into the wasted energy of public water systems

doesn’t typically generate large amounts of power: a few

hundred kilowatts at best. On the other hand, the exist-

ing infrastructure already provides almost everything

needed for a hydro system except the turbine/generator set. Public

utilities routinely bleed off excess pressure that could be put to

work simply by opening a coupling and bolting in a turbine. Even

though power output may be nominal, this low cost solution can

quickly pay for itself.

Unlike most hydro systems, however, energy recovery systems are

often subject to unusual constraints. For example, community water

usage directly affects ow, which can vary dramatically over the course

of a day. In addition, it is often necessary to maintain water pressure

at the turbine output to ensure adequate pressure for the community.

These factors can complicate the selection of turbine equipment.

It is also important to remember system priorities. The highest pri-

ority is uninterrupted water supply to the community, with power

generation coming in a distant second. These priorities can collide at

times. For example, if an electrical problem abruptly trips the genera-

tor ofine, water must continue to ow to the community even though

the turbine/generator may be suddenly freewheeling under no load.

Beyond technical issues, regulatory hurdles can significantly

delay an energy recovery project, if not kill it entirely. Conventional

wisdom would suggest approval would come quickly, since the entire

system is usually a simple revision of plumbing. But these low impact

projects are subject to the same regulatory processes as larger scale

hydro systems, in the US requiring FERC permitting and – surpris-

ingly – the need to deal with environmental opposition.

SOAR Technologies specialises in solving these types of problems

for communities. The company provides specialised turbine systems,

as well as assistance with feasibility assessment, technical design, and

the long journey toward regulatory approval. Over the past few years,

SOAR has installed energy recovery systems in Hawaii, Vermont,

Oregon, and other locations across the US.

TECHNICAL CHALLENGES

Two major issues are commonplace with water supply systems: varia-

ble ow and pressurised distribution to the community. These factors

create a challenging dilemma for hydro systems designers, especially

when encountered on the same project.

Variable ow, for example, would suggest the use of impulse tur-

bines such as Pelton or turgo. With a broad efciency curve, impulse

turbines can often deliver good performance down to 10% of design

ow. But a pressurised output complicates matters. Impulse turbines,

by denition, run in open air and typically employ a tailrace that is

not easily pressurised.

In contrast, reactive turbine types such as Francis and Kaplan oper-

ate well in a pressurized environment, since they are never exposed

to the atmosphere. As long as there is a pressure difference between

turbine input and output, reactive designs can produce power.

Unfortunately, they are less forgiving of wide swings in ow. Below

50% of design ow, efciency drops dramatically.

Then there is the issue of priority. By denition, community demand

determines ow rate; the power generation system cannot alter ow

in any way. Water must continue to ow unimpeded even when the

generator is suddenly thrown ofine. Impulse turbines have the advan-

tage here; a deector shield simply directs the stream of water away

from the runner without affecting ow. Reactive turbines are more of

a challenge since the ow of water always wants to spin the runner. In

addition, the resistance of the runner itself has an effect on ow.

All of the energy recovery systems installed by SOAR are designed

to run in parallel with the existing water system. This allows the tur-

bine/generator to be taken ofine for maintenance without impacting

the community water supply. Most systems use hydraulic actuators,

allowing switchover to be manual or automatic.

DEVELOPING THE GPRV

In 2004, SOAR participated in a research project to develop a gen-

erating pressure reducing valve (GPRV). SOAR worked with the

Energy recovery from

public water systems

Public water systems are often an ideal application for small hydro systems. The existing

water supply provides a nished intake and penstock, and in many cases a pressure

reducing valve can be bypassed with a hydro turbine that generates a positive return on

investment for the community. Michael Maloney reports.

A 35kW Pelton-type SOAR GPRV installed for the County of Hawaii

Department of Water Supply

WWW.WATERPOWERMAGAZINE.COM JULY 2010 19

SMALL HYDRO

California Energy Commission and San Diego State University to

develop a simple method for replacing existing PRVs with small

hydro systems. Over the course of several months a number of work-

ing test models were constructed to produce a preliminary design for

a pressurised impulse turbine system. SOAR later patented this design

for commercial production.

The original GPRV was essentially a Pelton turbine enclosed in a

sealed housing to maintain positive pressure at the tailrace. As with

all Pelton designs, the turbine runs in air, but the air is compressed

within a sealed chamber. SOAR teamed with Canyon Hydro to man-

ufacture this new design, and installed the rst GPRV unit in a water

system on the island of Hawaii.

This early version of the GPRV employed a vertical (horizontal

shaft) Pelton runner, coupled with a standard air compressor to

pressurise the system. The expected power output was achieved but

there were signicant issues with air entrainment. Air in the water is

not harmful; in fact, it tends to improve the water treatment process

downstream. But since air must be compressed to run the system,

and compressors require energy, any air loss down the pipeline is

essentially a loss of efciency. With the vertical runner design, the

compressor was running almost constantly to replenish lost air.

To better manage air entrainment, SOAR engineers ran extensive

computational uid dynamics simulations, resulting in development

of a new design that uses a horizontally-oriented (vertical shaft)

Pelton runner for signicantly improved operation. Using a horizon-

tal runner, the water tends to spin its way out of the turbine, helping

to separate the air before the water exits down the pipeline.

SOAR has also developed reactive versions of the GPRV using

Francis and reverse-pump designs. These fully immersed turbines

simplify pressurised operation but are constrained to a much nar-

rower operating range for changes in ow. In addition, special provi-

sions are necessary to accommodate continuous ow even when the

turbine trips ofine.

Flow through a Francis turbine changes drastically when generator

load is removed. A reactive turbine in an over-speed condition tends

to choke ow, an unacceptable scenario in a water supply system. To

alleviate this problem, SOAR developed a multi-stage Francis design

to maintain nearly constant ow in any situation.

The SOAR Francis GPRV uses a modied impeller design and uses

two to ve Francis runners in series. Head pressure determines the

number of runners in the system. Because space is often at a pre-

mium in existing water systems, runners are oriented vertically to save

room. Unlike conventional Francis turbines, the water inlet and outlet

are aligned to facilitate easy installation into an existing pipeline.

DETERMINING PROJECT FEASIBILITY

The growing global focus on green energy and sustainability has

sparked a sharp spike in interest for energy recovery systems. Water

supply systems are the most common application; however, there is

also potential for wastewater system applications.

Wastewater systems are generally more difcult to cost justify. They

tend to be low head, high ow environments, which require physi-

cally larger turbine systems to handle the additional ow. Because

physical size bears a direct relationship to turbine cost, SOAR has yet

to evaluate a wastewater application that forecasts a positive return

on investment.

When invited to assess the feasibility of a potential project, SOAR

focuses on four key parameters: head, ow, ow duration (variabil-

ity), and regulatory process. Most of our systems have been installed

for use with a net metering plan, where generator output offsets some

of the power normally purchased to run the plant. In effect, net meter-

ing pays the power producer retail rates for electricity, substantially

accelerating system payback.

Unfortunately, regulatory requirements are often a major obstacle.

Whenever public water and public power come together, approvals

from both FERC and the local power company are required. Currently

the lead time for gaining FERC approval of conduit projects is about

six months, and the FERC application itself usually takes at least

two months to prepare. Before submitting the application, multiple

agencies, environmental groups, tribal leaders and other stakeholders

must reach agreement.

Unfortunately, the cost to obtain regulatory approval sometimes

makes it impossible to justify an otherwise viable project. But good

news may be forthcoming. FERC has indicated that it will streamline

and simplify applications for energy recovery projects.

Most of the inquiries SOAR receives originate from local water

system operators. These are the hands-on water experts who know

their systems and can identify opportunities for energy recovery. Even

so, nearly every project requires buy-in at the executive level, and the

cost must always be justied. A good part of SOAR’s effort goes into

pulling many disparate groups together to ensure project success.

LOOKING AHEAD

Worldwide interest in energy recovery appears to be growing, and

SOAR anticipates more projects will emerge as word spreads between

water districts. Green energy, despite the economic slowdown, still

promises strong growth – especially on the heels of the disaster in

the Gulf of Mexico. As technologies such as the GPRV continue to

improve, and assuming the regulatory process is further streamlined,

future energy recovery projects should be easier to justify and faster to

implement.

Michael Maloney is president of SOAR Technologies,

a hydropower design and project consulting rm

based in Washington State, US.

Email: mmaloney@soartechinc.com.

www.soartechinc.com

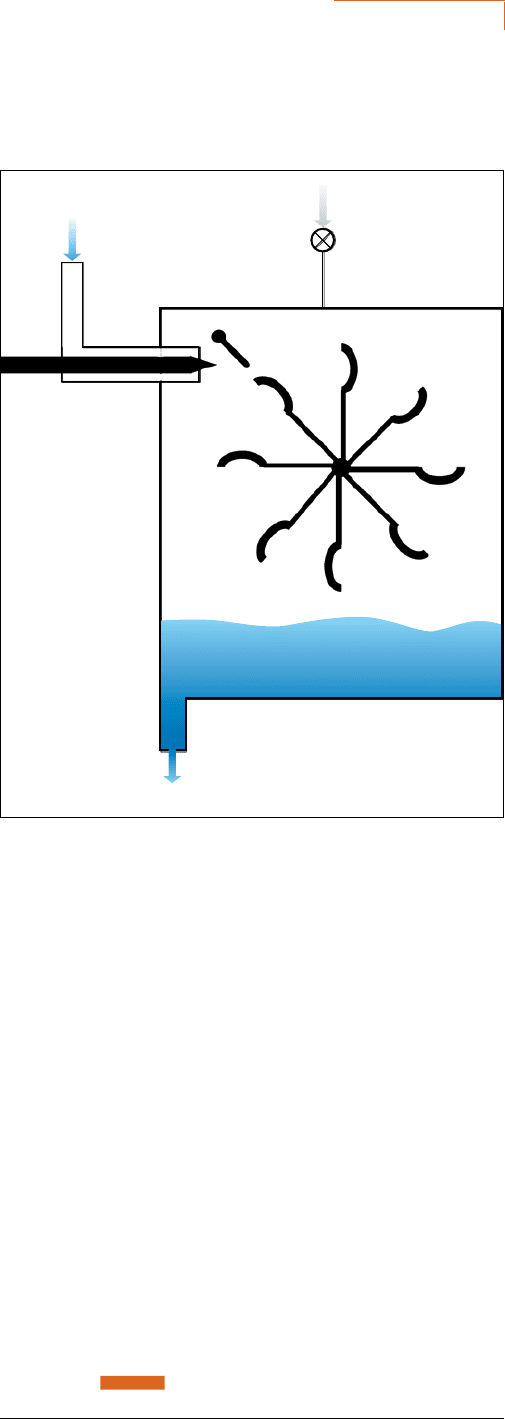

Water

Water out

Water in

Air in

Adjustable

needle valve

Deflector

Pressurized

chamber

IWP& DC

A line drawing of a Pelton-type GRPV. The SOAR Pelton-type GPRV pressuris-

es a sealed runner chamber with compressed air to maintain water pressure

at the outlet

20 JULY 2010 INTERNATIONAL WATER POWER & DAM CONSTRUCTION

TUNNELLING

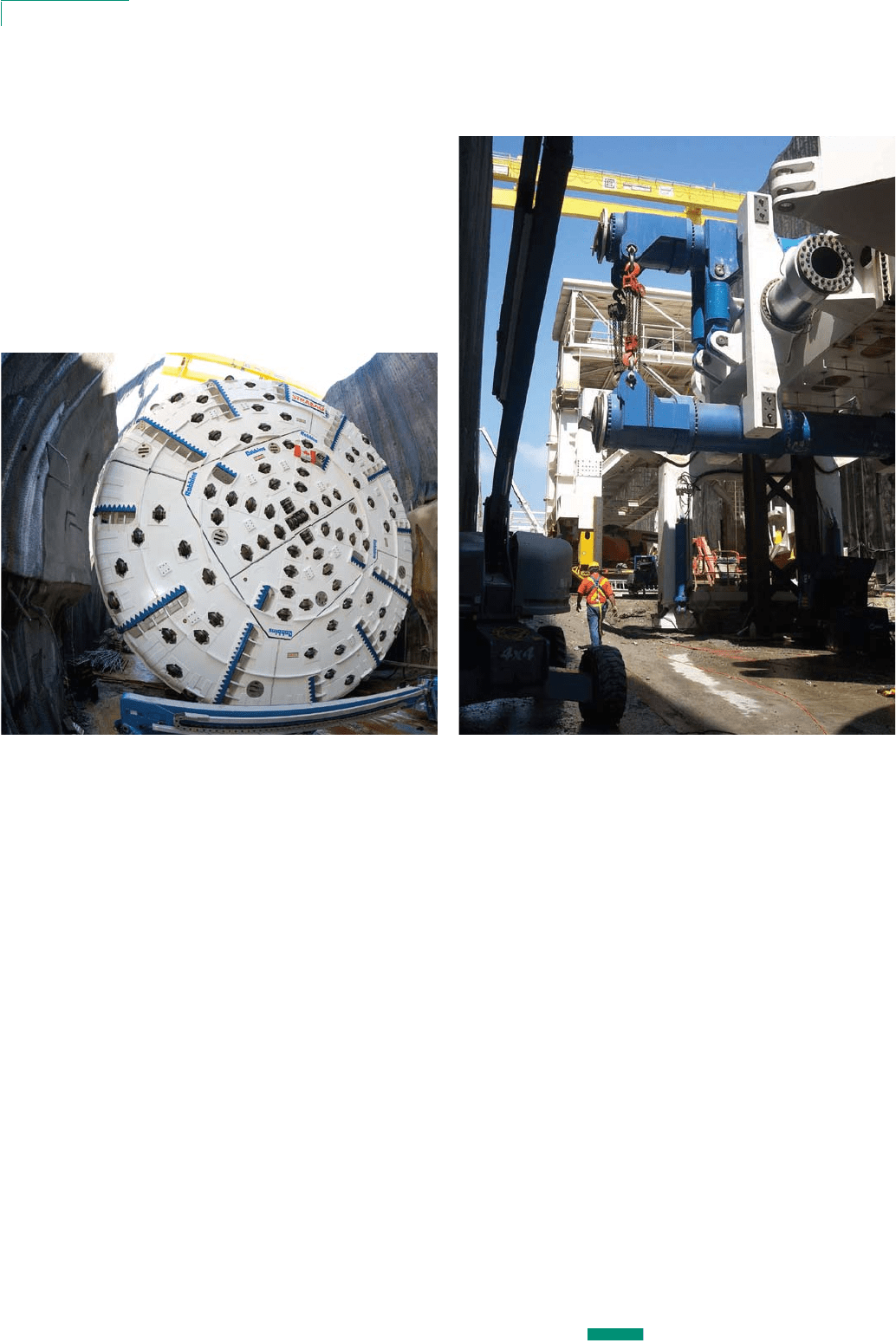

B

Y last moth more than two-thirds of the Niagara power

tunnel had been excavated by design-build contractor

Strabag for Ontario Power Generation (OPG) using a hard

rock TBM, which is driving along a realigned route fol-

lowing earlier geological difculties. All activities had resumed by

June following a stop for maintenance and to launch the concret-

ing work for the permanent arch lining over the tunnel invert.

The 14.4m diameter main beam TBM, manufactured by Robbins, had

bored more than 7km of its 10.2 km long power tunnel route by early

this month, says OPG’s project director, Rick Everdell. In its rst quarter

results, to 31 March, the utility reported that the TBM had advanced

almost 6.5km – progress of 2.7km over the previous 12 months.

With the alignment having been raised by 45m, the TBM is out

of the Queenston shale that had proven troublesome earlier in the

project and the machine is mostly now meeting whirpool sandstone

with tunnelling conditions further improving. “We are happy with

the current rock conditions and ground support system, as we haven’t

been short of challenges in the past,” said Strabag’s project manager,

Ernst Gschnitzer.

Niagara Tunnel Project will be the third headrace below Niagara Falls

and will help make use of the presently untapped allocation in Canada’s

share of the water under the 1950 Treaty with the US. The 12.8m i.d.

tunnel will convey a further 500m

3

/secs of water to the Sir Adam Back

complex and add an extra 1.6TWh/year of electricity generation.

The TBM – ‘Big Becky’ – is the largest hard rock machine manu-

factured and was also the rst that Robbins assembled at a project

site using its Onsite First Time Assembly (OFTA) system. The shield

was launched in September 2006 to drive from the outlet and passed

though 10 layers of near horizontal strata, comprising limestone,

dolomite, sandstone and then reaching shale.

Originally, the Niagara Tunnel project was to have been completed

by last month. However, extensive difculties with overbreak in the

Queenston shale led to delays and safety concerns. OPG has noted

that crown overbreak in the shale was up to 4m in depth into the

rock and averaged about 1.5m. Signicant modications were needed

behind the cutterhead to the initial support area for the excavated

rock and worker safety.

The revised ground support system comprised spiles, rock bolts,

mesh, steel straps and shotcrete. The grouted spiles are 9m long to

help contain overbreak, and the rockbolts are 4m long, but in leaving

the Queenston shale the need for the spiles lessened.

Last year the contract between OPG and Strabag was renegotiated

and the tunnel realigned. The revised schedule is for the contract to

be completed by the end of 2013 and the budget has been increased

by about 60% to approximately Can$1.6B (US$1.5B).

Also last year, in the third quarter, a further rock fall happened but

it was far back along the tunnel, more than 3km behind the TBM,

in a stretch of tunnel that had previously suffered from problems of

crown overbreak. No injuries were caused by the incident.

Work to re-complete the circular prole of the tunnel has now

advanced to approximately 1.8km, notes Everdell. By the end of Q1,

reported OPG, the arch lining had advanced 1km and by early May

the activity had progresses a further 300m. Everdell adds that now

there is almost no overbreak in the TBM drive with the crown in

Grimsby sandstone about 7km along the route.

The secondary, nal, lining for the tunnel will be formed of 600mm

thick continuously-poured concrete on a waterproof membrane.

Behind the TBM, almost 5km of the permanent lining for the invert

had been completed by May, and the activity has resumed following

the maintenance and outage activities. In its Q1 results, OPG said just

over 4.5km of permanent invert had been placed by 31 March.

Concreting works, to place the upper two-thirds ‘arch’ of the per-

manent lining over the invert began in late May, as planned, says

Everdell, and the activity is making progress.

OPG said the current progress should have the project completed

by the revised deadline and budget, possibly at less cost. The rene-

gotiated contract has incentives on delivery against the revised target

schedule and cost.

Progress is pushing ahead on OPG’s

Niagara power tunnel after earlier geological

difculties. By Patrick Reynolds

IWP& DC

Niagara progress

The Robbins Main Beam was the

first ever TBM initially assem-

bled at the jobsite using OFTA