Tietenberg Tom, Lewis Lynne. Environmental & Natural Resource Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

461Possible Reforms

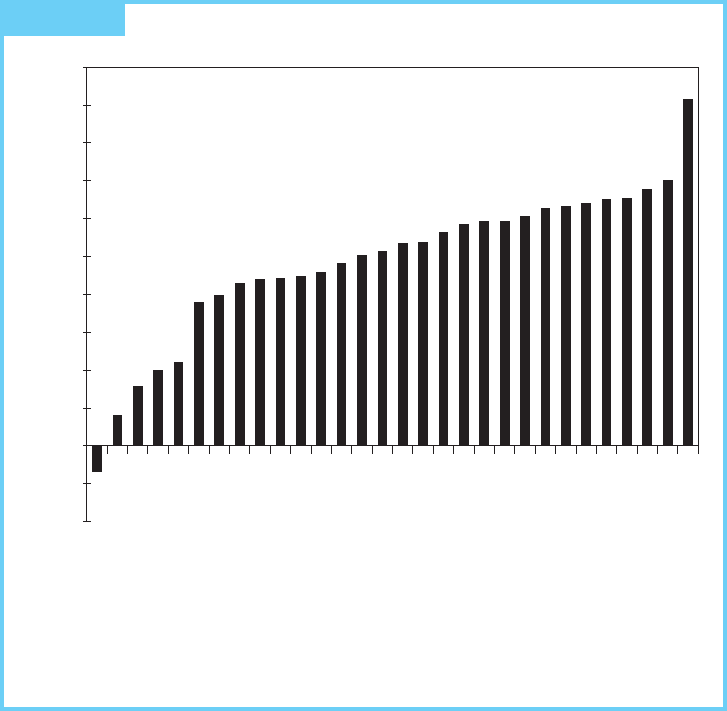

include local pollution, congestion, and accidents. Fuel external costs, such as oil

dependency and climate change, are another $0.18 per gallon. Figure 17.2

illustrates current fuel taxes by country. These data suggest current fuel taxes would

have to be much higher in many countries in order to internalize the full social cost

of road transport.

But fuel taxes are not the only way to begin to internalize costs, and, by

themselves, they would be a blunt instrument anyway because typically they would

not take into account when and where the emissions occurred. One way to focus on

these temporal and spatial concerns is through congestion pricing.

Congestion Pricing

Congestion is influenced not only by how many vehicle miles are traveled, but

also where and when the driving occurs. Congestion pricing addresses the spatial

and temporal externalities by charging for driving on congested roads or at

$5.00

$4.50

$4.00

$3.50

$3.00

$2.50

$2.00

$1.50

$1.00

$0.50

$0.00

–$0.50

Italy

United States

Canada

New Zealand

Australia

Iceland

Poland

Japan

Korea

Spain

Hungary

Austria

Luxembourg

Czech Republic

Switerzerland

Slovak Republic

Sweden

Ireland

Belgium

Denmark

Portugal

France

Greece

Norway

Finland

United Kingdom

Germany

Netherlands

Turkey

–$1.00

Mexico

FIGURE 17.2 2006 Fuel Taxes in Selected Countries

Source

: Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OEDC) & European Environment Agency (EEA)

Economic Instruments Database, “Comparisons of developments in tax rates over time,” http://www2.oecd.org/

ecoinst/queries/UnleadedPetrolEuro.pdf

Note:

Tax rates are federal, with the exception of the United States and Canada, which include average

state/provincial taxes.

462 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

congested times. Four different types of congestion pricing mechanisms are in

current use: (1) cordon (area or zonal) pricing; (2) facilities pricing; (3) pricing

lanes; and (4) high occupancy toll (HOT) lanes.

7

Congestion pricing of roads or

zones has recently been gaining considerable attention as a targeted remedy for

these time- and space-specific pollutant concentrations.

Toll rings have existed for some time in Oslo, Norway, and Milan, Italy.

In the United States, electronic toll collection systems are currently in place in

many states. Express lanes for cars with electronic meters reduce congestion at

toll booths. Reserved express bus lanes during peak hour periods are also

common in the United States for congested urban highways. (Reserved lanes for

express buses lower the relative travel time for bus commuters, thereby

providing an incentive for passengers to switch from cars to buses.) High

occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes have also been established for some highways.

During certain hours, vehicles traveling in the HOV lanes must have more

than one passenger. Honolulu, Hawaii, has a high occupancy “zipper lane.”

The zipper lane is in the middle of the highway; in the morning commute hours

the traffic travels toward Honolulu and by mid-afternoon the lane is literally

zipped up on one side and unzipped on the other, creating an additional lane for

the outgoing evening commute.

Several Asian cities have also undertaken some innovative approaches. Perhaps

the most far-reaching can be found in Singapore, where the price system is used to

reduce congestion (Example 17.4). Bangkok bars vehicles from transporting goods

from certain parts of the metropolitan area during various peak hours, leaving the

roads available to buses, cars, and motorized tricycles.

Safirova et al. (2007) compare six different road-pricing instruments all aimed at

internalizing the congestion externality. These include three types of cordon

pricing schemes (area-based congestion taxes): a distance-based toll on highways, a

distance-based toll on metro roads only, and a gas tax. Examining the effectiveness

of these instruments for the Washington, DC, metropolitan area in 2000, they

explicitly model how residential choice (and hence travel time) could be affected by

the type of policy instrument employed. The question they ask is, “But how do

policies designed to address congestion alone fare, once the many other

consequences associated with driving—traffic accidents, air pollution, oil

dependency, urban sprawl, and noise, to name a few—are taken into account?”

8

They find that using “social-cost pricing” (incorporating the social costs of driving)

instead of simple congestion pricing affects the outcome of instrument choice.

Specifically, when the policy goal is solely to reduce congestion, variable time-

of-day pricing on the entire road network is the most effective and efficient policy.

However, when additional social costs are factored in, the vehicle miles traveled

(VMT) tax is almost as efficient.

7

Congressional Budget Office (2009) “Using Pricing to Reduce Traffic Congestion,” Washington, DC,

A CBO Study.

8

http://www.rff.org/rff/News/Releases/2008Releases/MarginalSocialCostTrafficCongestion.cfm

463Possible Reforms

Private Toll Roads

New policies are also being considered to ensure that road users pay all the costs of

maintaining the highways, rather than transferring that burden to taxpayers. One strat-

egy, which has been implemented in Mexico and in Orange County, California, is to

allow construction of new private toll roads. The tolls are set high enough to recover all

construction and maintenance costs and in some cases may include congestion pricing.

Zonal Mobile-Source Pollution-Control Strategies:

Singapore

Singapore has one of the most comprehensive strategies to control vehicle

pollution in the world. In addition to imposing very high vehicle-registration fees,

this approach also includes the following:

●

Central Business District parking fees that are higher during normal

business hours than during the evenings and on weekends.

●

An area-licensing scheme that requires the display of an area-specific

purchased vehicle license in order to gain entry to restricted downtown

zones during restricted hours. These licenses are expensive and penalties

for not having them displayed when required are very steep.

●

Electronic peak-hour pricing on roadways. These charges, which are

deducted automatically using a “smart card” technology, vary by roadway

and by time of day. Conditions are reviewed and charges are adjusted

every three months.

●

An option for people to purchase an “off-peak” car. Identified by a

distinctive red license plate that is welded to the vehicle, these vehicles

can only be used during off-peak periods. Owners of these vehicles pay

much lower registration fees and road taxes.

●

Limiting the number of new vehicles that can be registered each year. In order

to ensure that they can register a new car, potential buyers must first secure

one of the fixed number of licenses by submitting a winning financial bid.

●

An excellent mass-transit system that provides a viable alternative to

automobile travel.

Has the program been effective? Apparently, it has been quite effective in two

rather different ways. First, it has provided a significant amount of revenue for the

government, which the government can use to reduce more burdensome taxes.

(The revenues go into the General Treasury; they are not earmarked for the trans-

port sector.) Second, it has caused a large reduction in traffic-related pollution in

the affected areas. The overall levels of carbon monoxide, lead, sulfur dioxide, and

nitrogen dioxide are now all within the human-health guidelines established by

both the World Health Organization and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Source

: N. C. Chia and Stock-Young Phang. “Motor Vehicle Taxes as an Environmental Management

Instrument: The Case of Singapore,”

Environmental Economics and Policy Studies

Vol. 4, No. 2 (2001),

pp. 67–93.

EXAMPLE

17.4

464 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

Parking Cash-Outs

Providing parking spaces for employees costs employers money, yet most of them

provide this benefit free of charge. This employer-financed subsidy reduces one

significant cost of driving to work. Since this subsidy only benefits those who drive

to work, it lowers the relative cost of driving vis-à-vis all other transport choices,

such as walking, biking, and public transport. Most of those choices create much less

air pollution; therefore, the resulting bias toward driving creates an inefficiently

high level of pollution.

One way to rectify this bias is for employers to compensate employees who do

not use a parking space with an equivalent increase in income. This would transfer

the employer’s savings in not having to provide a parking spot to the employee and

remove the bias toward driving to work.

Feebates

Some research has found that consumers may undervalue fuel economy. One study

found that consumers only consider the first three years of fuel savings when

choosing a more fuel-efficient vehicle. This understates the value of fuel savings by

up to 60 percent (NRC, 2002). To remedy this undervaluation bias among

consumers purchasing new vehicles, feebates combine taxes on purchases of new

high-emitting (or high-fuel-consumption) vehicles with subsidies for purchases of

new low-emitting/low-fuel-consumption vehicles. By raising the relative cost of

high-emitting vehicles, it encourages consumers to take the environmental effects

of those vehicles into account. Feebate system structures are based on a boundary

that separates vehicles charged a tax from those entitled to rebates. The simplest

feebate structure uses a constant dollar rate per gallon of fuel consumed (Greene

et al., 2005). The revenue from the taxes can serve as the financing for the subsi-

dies, but previous experience indicates that policies such as this are rarely revenue-

neutral; the subsidy payouts typically exceed the revenue from the fee. Feebates are

not yet widely used, but Ontario, Canada, and Austria have implemented feebates.

Greene et al. (2005) find that feebates achieve fuel economy increases that are two

times higher than those achieved by either rebates or gas guzzler taxes alone.

Pay-As-You-Drive (PAYD) Insurance

Another possibility for internalizing an environmental externality associated with

automobile travel, thereby reducing both accidents and pollution, involves chang-

ing the way car insurance is financed. As Example 17.5 illustrates, small changes

could potentially make a big difference.

Accelerated Retirement Strategies

A final reform possibility involves strategies to accelerate the retirement of older,

polluting vehicles. This could be accomplished either by raising the cost of holding

onto older vehicles (as with higher registration fees for vehicles that pollute more) or

by providing a bounty of some sort to those retiring heavily polluting vehicles early.

465Possible Reforms

Under one version of a bounty program, stationary sources were allowed to

claim emissions reduction credits for heavily polluting vehicles that were removed

from service. Heavily polluting vehicles were identified either by inspection and

maintenance programs or remote sensing. Vehicle owners could bring their

vehicle up to code, usually an expensive proposition, or they could sell it to the

company running the retirement program. Purchased vehicles are usually

disassembled for parts and the remainder is recycled. The number of emissions

reduction credits earned by the company running the program depends on such

factors as the remaining useful life of the car and the estimated number of miles it

would be driven and is controlled so that the transaction results in a net increase in

air quality.

Another accelerated retirement approach was undertaken in 2009 as a means to

stimulate the economic recovery, while reducing emissions. Example 17.6 explores

how well this Cash-for-Clunkers Program worked.

Modifying Car Insurance as an Environmental

Strategy

Although improvements in automobile technology (such as air bags and antilock

brakes) have made driving much safer than in the past, the number of road deaths

and injuries is still inefficiently high. Since people do not consider the full societal

cost of accident risk when deciding how much and how often to drive, the number

of vehicle miles traveled is excessive. Although drivers are very likely to take into

account the risk of injury to themselves and family members, other risks are likely

to be externalized. They include the risk of injury their driving poses for other

drivers and pedestrians, the costs of vehicular damage that is covered through

insurance claims, and the costs to other motorists held up in traffic congestion

caused by accidents. Externalizing these costs artificially lowers the marginal cost

of driving, thereby inefficiently increasing the pollution from the resulting high

number of vehicle miles.

Implementing PAYD insurance could reduce those inefficiencies. With PAYD

insurance, existing rating factors (such as age, gender, and previous driving

experience) would be used by insurance companies to determine a driver’s

per-mile rate, and this rate would be multiplied by annual miles driven to calculate

the annual insurance premium. This approach has the effect of drastically

increasing the marginal cost of driving an extra mile without raising the amount

people spend annually on insurance. Estimates by Harrington and Parry (2004)

suggest that calculating these insurance costs on a per-mile basis would have the

same effect as raising the federal gasoline tax from $0.184 to $1.50 per gallon for

a vehicle that gets 20 miles per gallon. This is a substantial increase and could

have a dramatic effect on people’s transport choices (and, therefore, the pollution

they emit) despite the fact that it imposes no additional financial burden on them.

Source

: Winston Harrington and Ian Parry, “Pay-As-You-Drive for Car Insurance.” NEW APPROACHES ON

ENERGY AND THE ENVIRONMENT: POLICY ADVICE FOR THE PRESIDENT, by R. Morgenstern and

P. Portney, eds., (Washington, DC: Resources of the Future, 2004), pp. 53–56.

EXAMPLE

17.5

466 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

We also have learned some things about what doesn’t work very well. One

increasingly common strategy involves limiting the days any particular vehicle can

be used, as a means of limiting miles traveled. As Example 17.7 indicates, this

strategy can backfire!

The Car Allowance Rebate System: Did it Work?

On July 27, 2009, the Obama administration launched the Car Allowance Rebate

System (CARS), known popularly as “Cash for Clunkers.” This federal program had

two goals: to provide stimulus to the economy by increasing auto sales, and to

improve the environment by replacing old, fuel-inefficient vehicles with new,

fuel-efficient ones.

Under the CARS program, consumers received a $3,500 or $4,500 discount

from a car dealer when they traded in their old vehicle and purchased or leased a

new, qualifying vehicle. In order to be eligible for the program, the trade-in

passenger vehicle had: (1) to be manufactured less than 25 years before the date

it was traded in; (2) to have a combined city/highway fuel economy of 18 miles

per gallon or less; (3) to be in drivable condition; and (4) to be continuously

insured and registered to the same owner for the full year before the trade-in. The

end date was set at November 1, 2009, or whenever the money ran out. Since

the latter condition prevailed, the program terminated on August 25, 2009.

During the program’s nearly one-month run, it generated 678,359 eligible

transactions at a cost of $2.85 billion. Using Canada as the control group, one

research group (Li et al., 2010) found that the program significantly shifted sales to

July and August from other months.

In terms of environmental effects, this study found that the program

resulted in a cost per ton ranging from $91 to $301, even including the benefits

from reducing criteria pollutants. This is substantially higher than the per ton

costs associated with other programs to reduce emissions, a finding that is

consistent with other studies (Knittel, 2009). In addition, the program was

estimated to have created 3,676 job-years in the auto assembly and parts

industries from June to December of 2009. That effect decreased to 2,050

by May 2010.

In summary, this study found mixed results. An increase in sales did occur, but

much of it was simply shifting sales that would have occurred either earlier or later

into July and August. And while it did produce positive environmental benefits,

the approach was not a cost-effective way to achieve those benefits. This case

study illustrates a more general principle, namely that trying to achieve two policy

objectives with a single policy instrument rarely results in a cost-effective

outcome.

Sources

: United States Government Accountability Office, Report to Congressional Committees:

Lessons Learned from Cash for Clunkers Program Report # GAO-10-486 (2010); Shanjun Li, Joshua Linn,

and Elisheba Spiller. “

Evaluating ‘Cash-for-Clunkers’: Program Effect on Auto Sales, Jobs and the

Environment”

(Washington, DC: Resources for the Future Discussion Paper 10–39); and Christopher

R. Knittel, “The Implied Cost of Carbon Dioxide Under the Cash for Clunkers Program” (August 31, 2009).

Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1630647

EXAMPLE

17.6

467Summary

Summary

The current policy toward motor vehicle emissions blends point-of-production

control with point-of-use control. It began with uniform emissions standards.

Grams-per-mile emissions standards, the core of the current approach in the

United States and Europe, have had, in practice, many deficiencies. While they

have achieved lower emissions per mile, they have been less effective in lowering

aggregate emissions and in ensuring cost-effective reductions.

Aggregate mobile-source emissions have been reduced by less than expected

because of the large offsetting increase in the number of miles traveled. Unlike

sulfur emissions from power plants, aggregate mobile-source emissions are not

capped, so as miles increase, emissions increase.

The efficiency of the emissions standards has been diminished by their

geographic uniformity. Too little control has been exercised in highly polluted

areas, and too much control has been exercised in areas with air quality that exceeds

the ambient standards.

Local approaches, such as targeted inspection and maintenance strategies and

accelerated retirement strategies, have had mixed success in redressing this

imbalance. Since a relatively small number of vehicles are typically responsible for

a disproportionately large share of the emissions, a growing reliance on remote

sensing to identify the most polluting vehicles is allowing the policy to target

resources where they will produce the largest net benefit.

Counterproductive Policy Design

As one response to unacceptably high levels of traffic congestion and air pollution,

the Mexico City administration imposed a regulation that banned each car from

driving on a specific day of the week. The specific day when the car could not be

driven was determined by the last digit of the license plate.

This approach appeared to offer the opportunity for considerable reductions in

congestion and air pollution at a relatively low cost. In this case, however, the

appearance was deceptive because of the way in which the population reacted to

the ban.

An evaluation of the program by the World Bank found that in the short run the

regulation was effective. Pollution and congestion were reduced. However, in the

long run the regulation not only was ineffective, it was also counterproductive

(paradoxically it increased the level of congestion and pollution). This paradox

occurred because a large number of residents reacted by buying an additional car

(which would have a different banned day), and once the additional cars became

available, total driving actually increased. Policies that fail to anticipate and

incorporate behavior reactions run the risk that actual and expected outcomes

may diverge considerably.

Source

: Gunnar S. Eskeland and Tarhan Feyzioglu. “Rationing Can Backfire: The ‘Day Without a Car

Program’ in Mexico City,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 1554 (December 1995).

EXAMPLE

17.7

468 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

The historic low cost of auto travel has led to a dispersed pattern of development.

Dispersed patterns of development make mass transit a less-viable alternative, which

causes a downward spiral of population dispersal and low mass-transit ridership. In the

long run, part of the strategy for meeting ambient standards will necessarily involve

changing land-use patterns to create the kind of high-density travel corridors that are

compatible with effective mass-transit use. Though these conditions already exist in

much of Europe, it is likely to evolve in the United States over a long period of time.

Ensuring that the true social costs of transportation are borne by those making resi-

dential and mode-of-travel choices will start the process moving in the right direction.

A couple of important insights about the conventional environmental policy

wisdom can be derived from the history of mobile-source control. Contrary to the

traditional belief that tougher laws produce more environmental results, the

sanctions associated with meeting the grams-per-mile emissions standards were so

severe that, when push came to shove, authorities were unwilling to impose them.

Threatened sanctions will only promote the desired outcome if the threat is

credible. The largest “club” is not necessarily the best “club.”

The second insight confronts the traditional belief that simply applying the

right technical fix can solve environmental problems. The gasoline additive MTBE

was advanced as a way to improve the nation’s air. With the advantage of hindsight,

we now know that its pollution effects on groundwater have dwarfed its positive

effects on air quality. Though technical fixes can, and do, have a role to play in

environmental policy, they also can have large, adverse, unintended consequences.

Looking toward the future of mobile-source air pollution control, two new

emphases are emerging. The first involves encouraging the development and

commercialization of new, cleaner automotive technologies ranging from gas-electric

hybrids to fuel-cell vehicles powered by hydrogen. Policies such as fuel-economy

standards, gasoline taxes, feebates, and sales quotas imposed on auto manufacturers

for low-emitting vehicles are designed to accelerate their entry into the vehicle fleet.

The second new emphasis focuses on influencing driver choices. The range of

available policies is impressive. One set of strategies focuses on bringing the private

marginal cost of driving closer to the social marginal cost through such measures as

congestion pricing and Pay-As-You-Drive auto insurance. Others, such as parking

cash-outs, attempt to create a more level playing field for choices involving the

mode of travel for the journey to work.

Complicating all of these strategies is the increased demand for cars in developing

countries. In 2007, Tata Motors, the Indian automaker, introduced “the world’s

cheapest car,” the Tata Nano. The Nano sells for about 100,000 rupees (US $2,500).

Tata Motors expects to sell millions of these affordable, stripped-down vehicles. Fuel

efficiency of these cars is quite good (over 50 mpg), but the sheer number of vehicles

implies sizable increases in the demand for fuel, congestion, and pollution emissions.

Appropriate regulation of emissions from mobile sources requires a great deal

more than simply controlling the emissions from vehicles as they leave the factory.

Vehicle purchases, driving behavior, fuel choice, and even residential and employ-

ment choices must eventually be affected by the need to reduce mobile-source

emissions. Affecting the choices facing automobile owners can only transpire if the

economic incentives associated with those choices are structured correctly.

469Further Reading

Discussion Questions

1. When a threshold concentration is used as the basis for pollution control, as

it is for air pollution, one possibility for meeting the threshold at minimum

cost is to spread the emissions out over time. To achieve this, one might

establish a peak-hour pricing system that charges more for emissions during

peak periods.

a. Would this represent a movement toward efficiency? Why or why not?

b. What effects should this policy have on mass-transit usage, gasoline sales,

downtown shopping, and travel patterns?

2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of using an increase in the gasoline

tax to move road transport decisions toward both efficiency and sustainability?

Self-Test Exercises

1. “While gasoline taxes and fuel economy standards can both be effective in

increasing the number of miles per gallon in new vehicles, gasoline taxes are

superior means of reducing emissions from the vehicle fleet.” Discuss.

2. Suppose the nation wishes to reduce gasoline consumption not only to

promote national security, but also to reduce the threats from climate change.

a. How effective is a strategy relying on the labeling of the fuel efficiency of

new cars likely to be? What are some of the advantages or disadvantages of

this kind of approach?

b. How effective would a strategy targeting the retirement of old, fuel-

inefficient vehicles be? What are some of the advantages or disadvantages

of this kind of approach?

c. Would it make any economic sense to combine either of these polices with

pay-as-you-drive insurance? Why or why not?

3. a. If a pay-as-you-drive insurance program is being implemented to cope

with automobile related externalities associated with driving, what factors

should be considered in setting the premium?

b. Would you expect a private insurance company to take all these factors

into account? Why or why not?

Further Reading

Button, Kenneth J. Market and Government Failures in Environmental Management: The Case

of Transport (Paris: OECD, 1992). Analyzes and documents the types of government

interventions such as pricing, taxation, and regulations that often result in environmental

degradation.

Crandall, Robert W., Howard K. Gruenspecht, Theodore E. Keeler, and Lester B. Lave.

Regulating the Automobile (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1986). An examination

470 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

of the effectiveness and efficiency of the federal regulation of automobile safety, emissions,

and fuel economy in the United States.

Harrington, Winston, and Virginia McConnell. “Motor Vehicles and the Environment,” in

H. Folmer and T. Tietenberg, eds. International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource

Economics 2003/2004 (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2003): 190–268. A comprehen-

sive survey of what we have learned from economic analysis about cost-effective ways to

control pollution from motor vehicles.

MacKenzie, James J. The Keys to the Car: Electric and Hydrogen Vehicles for the 21st Century

(Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 1994). Surveys the environmental and

economic costs and benefits of alternative fuels and alternative vehicles.

Mackenzie, James J., Roger C. Dower, and Donald D. T. Chen. The Going Rate: What It

Really Costs to Drive (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 1992). Explores the

full cost of a transportation system dominated by the automobile.

OECD. Cars and Climate Change (Paris: OECD, 1993). Examines the possibilities, princi-

pally from enhanced energy efficiency and alternative fuels, for reducing greenhouse

emissions from the transport sector.

Additional References and Historically Significant References are available on this book’s

Companion Website: http://www.pearsonhighered.com/tietenberg/.