Tietenberg Tom, Lewis Lynne. Environmental & Natural Resource Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

441Further Reading

Stern, Nicholas. “The Economics of Climate Change,” American Economic Review

Vol. 98, No. 2 (2008): 1–37. A recent assessment by the former chief economist of the

World Bank.

Stavins, Robert N. “Addressing Climate Change with a Comprehensive US Cap-and-Trade

System,” Oxford Review of Economic Policy Vol. 24, No. 2 (2008): 298–321. Describes

considerations for designing a cap-and-trade policy to control greenhouse gas emissions

in the United States.

Tacconi, Luca, Sango Mahanty, and Helen Suich, eds. Payments for Environmental Services,

Forest Conservation and Climate Change: Livelihoods in the REDD? (Cheltenham, UK:

Edward Elgar, 2011). This collection of essays examines carbon-focused payments for

environmental services schemes from three tropical continents.

Additional References and Historically Significant References are available on this book’s

Companion Website: http://www.pearsonhighered.com/tietenberg/

442

17

17

Mobile-Source Air Pollution

There are two things you shouldn’t watch being made, sausage and law.

—Anonymous

Introduction

Although they emit many of the same pollutants as stationary sources, mobile sources

require a different policy approach. These differences arise from the mobility of the

source, the number of vehicles involved, and the role of the automobile in the

modern lifestyle.

Mobility has two major impacts on policy. On the one hand, pollution is partly

caused by the temporary location of the source—a case of being in the wrong place

at the wrong time. This occurs, for example, during rush hour in metropolitan

areas. Since the cars have to be where the people are, relocating them—as might be

done with electric power plants—is not a viable strategy. On the other hand, it is

more difficult to tailor vehicle emissions rates to local pollution patterns, since any

particular vehicle may end up in many different urban and rural areas during the

course of its useful life.

Mobile sources are also more numerous than stationary sources. In the United

States, for example, while there are approximately 27,000 major stationary sources,

well over 250 million motor vehicles have been registered, a number that has been

growing steadily since the 1960s when there were 74 million (U.S. Bureau

of Transportation Statistics). Enforcement is obviously more difficult as the

number of sources being controlled increases. Additionally, in the United States

alone, 33 percent of carbon emissions from anthropogenic sources come from

the transportation sector, 60 percent of which comes from the combustion of

gasoline by motor vehicles. As discussed in Chapter 16, creating incentives to

reduce human-induced sources of carbon emissions is a large focus for environ-

mental policy makers. When the sources are mobile, the problem of creating

appropriate incentives is even more complex.

Where stationary sources generally are large and run by professional managers,

automobiles are small and run by amateurs. Their small size makes it more difficult

to control emissions without affecting performance, while amateur ownership

makes it more likely that emissions control will deteriorate over time due to a lack

of dependable maintenance and care.

These complications might lead us to conclude that perhaps we should ignore

mobile sources and concentrate our control efforts solely on stationary sources.

Unfortunately, that is not possible. Although each individual vehicle represents a

miniscule part of the problem, mobile sources collectively represent a significant

proportion of three criteria pollutants—ozone, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen

dioxide—as well as a significant source of greenhouse gases.

For two of these—ozone and nitrogen dioxide—the process of reaching

attainment has been particularly slow. With the increased use of diesel engines,

mobile sources are becoming responsible for a rising proportion of particulate

emissions, and vehicles that burn leaded gasoline were, until legislation changed

the situation, a major source of airborne lead.

Since it is necessary to control mobile sources, what policy options exist? What

points of control are possible and what are the advantages or disadvantages of each?

In exercising control over these sources, the government must first specify the

agent charged with the responsibility for the reduction. The obvious candidates are

the manufacturer and the owner-driver. The balancing of this responsibility

should depend on a comparative analysis of costs and benefits, with particular

reference to such factors as (1) the number of agents to be regulated; (2) the rate of

deterioration while in use; (3) the life expectancy of automobiles; and (4) the

availability, effectiveness, and cost of programs to reduce emissions at the point of

production and at the point of use.

While automobiles are numerous and ubiquitous, they are manufactured by a

small number of firms. It is easier and less expensive to administer a system

that controls relatively few sources, so regulation at the production point has

considerable appeal.

Some problems are associated with limiting controls solely to the point of

production, however. If the factory-controlled emissions rate deteriorates during

normal usage, control at the point of production may buy only temporary

emissions reduction. Although the deterioration of emissions control can be

combated with warranty and recall provisions, the costs of these supporting

programs have to be balanced against the costs of local control.

Automobiles are durable, so new vehicles make up only a relatively small

percentage of the total fleet of vehicles. Therefore, control at the point of production,

which affects only new equipment, takes longer to produce a given reduction in

aggregate emissions because newer, controlled cars replace old vehicles very slowly.

Control at the point of production produces emissions reductions more slowly than a

program securing emissions reductions from used as well as new vehicles.

Some possible means of reducing mobile-source pollution cannot be accomplished

by regulating emissions at the point of production because they involve choices made

by the owner-driver. The point-of-production strategy is oriented toward reducing

the amount of emissions per mile driven in a particular type of car, but only the owner

can decide what kind of car to drive, as well as when and where to drive it.

These are not trivial concerns. Diesel and hybrid automobiles, buses, trucks, and

motorcycles emit different amounts of pollutants than do standard gasoline-

powered automobiles. Changing the mix of vehicles on the road affects the amount

and type of emissions even if passenger miles remain unchanged.

443Introduction

444 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

Where and when the car is driven is also important. Clustered emissions cause

higher concentration levels than dispersed emissions; therefore, driving in urban

areas causes more environmental damage than driving in rural areas. Local control

strategies could internalize these location costs; a uniform national strategy

focusing solely on the point of production could not.

Timing of emissions is particularly important because conventional commuting

patterns lead to a clustering of emissions during the morning and evening rush

hours. Indeed, plots of pollutant concentrations in urban areas during an average

day typically produce a graph with two peaks corresponding to the two rush hours.

1

Since high concentrations are more dangerous than low concentrations, some

spreading over the 24-hour period could also prove beneficial.

The Economics of Mobile-Source Pollution

Vehicles emit an inefficiently high level of pollution because their owner-drivers

are not bearing the full cost of that pollution. This inefficiently low cost, in turn,

has two sources: (1) implicit subsidies for road transport and (2) a failure by drivers

to internalize external costs.

Implicit Subsidies

Several categories of the social costs associated with transporting goods and people

over roads are related to mileage driven, but the private costs do not reflect that

relationship. For example:

●

Road construction and maintenance costs, which are largely determined by

vehicle miles, are mostly funded out of tax dollars. On average, states raise

only 38 percent of their road funds from fuel taxes. The marginal private cost

of an extra mile driven on road construction and maintenance funded from

general taxes is zero, but the social cost is not.

●

Despite the fact that building and maintaining parking space is expensive,

parking is frequently supplied by employers at no marginal cost to the

employee. The ability to park a car for free creates a bias toward private auto

travel since other modes receive no comparable subsidy.

Other transport subsidies create a bias toward gas-guzzling vehicles that produce

inefficiently high levels of emissions. In the United States, one example not long

ago was that business owners who purchased large, gas-guzzling sport utility

vehicles (SUVs) received a substantial tax break worth tens of thousands of dollars,

while purchasers of small energy-efficient cars received none (Ball and

Lundegaard, 2002). (Only vehicles weighing over 6,000 pounds qualified.)

1

The exception is ozone, formed by a chemical reaction involving hydrocarbons and nitrogen oxides in the

presence of sunlight. Since, for the evening rush-hour emissions, too few hours of sunlight remain for the

chemical reactions to be completed, graphs of daily ozone concentrations frequently exhibit a single peak.

445The Economics of Mobile-Source Pollution

This tax break was established 20 years earlier for “light trucks,” primarily to

benefit small farmers who depended upon the trucks for chores around the farms.

More recently, most purchasers of SUVs, considered “light trucks” for tax purposes,

have nothing to do with farming.

Externalities

Road users also fail to bear the full cost of their choices because many of the costs

associated with those choices are actually borne by others. For example:

●

The social costs associated with accidents are a function of vehicle miles.

The number of accidents rises as the number of miles driven rises. Generally

the costs associated with these accidents are paid for by insurance, but the

premiums for these insurance policies rarely reflect the mileage–accident

relationship. As a result, the additional private cost of insurance for additional

miles driven is typically zero, although the social cost is certainly not zero.

●

Road congestion creates externalities by increasing the amount of time

required to travel a given distance. Increased travel times also increase the

amount of fuel used.

●

The social costs associated with greenhouse gas emissions are also a function

of vehicle miles. These costs are rarely borne by driver of the vehicle.

●

Recent studies have indicated high levels of pollution inside vehicles, caused

mainly by the exhaust of cars in front.

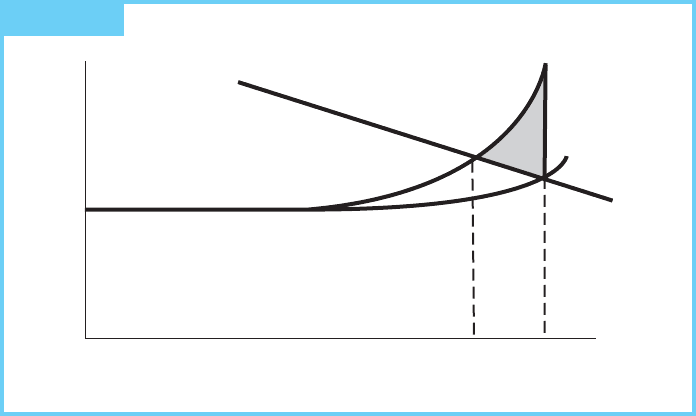

To elaborate on the congestion point, consider Figure 17.1. As traffic volumes

get closer to the design capacity of the roadway, traffic flow decreases; it takes more

time to travel between two points. At this point, the marginal private and social

$/Unit

A

B

C

D

Marginal

Social Cost

Demand

Marginal

Private Cost

Traffic Volume to Road Capacity

0.50 1.00V

e

V

p

FIGURE 17.1 Congestion Inefficiency

446 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

costs begin to diverge. The driver entering a congested roadway will certainly

consider the extra time it will take her to travel that route, but she will not consider

the extra time that her presence imposes on everyone else; it is an externality.

The efficient ratio of traffic volume to road capacity (V

e

) occurs where the

marginal benefits (as revealed by the demand curve) equal the marginal social cost.

Because individual drivers do not internalize the external costs of their presence on

this roadway, too many drivers will use the roadway and traffic volume will be too

high (V

p

). The resulting efficiency losses would be measured by the triangle ACD

(the shaded area). One recent study estimates that highway congestion in 2005

caused 4.2 billion hours of delay, 2.9 billion gallons of additional fuel to be used,

resulting in a cost of $78 billion to highway users.

2

Consequences

Understated road transport costs create a number of perverse incentives. Too many

roads are crowded. Too many miles are driven. Too many trips are taken. Transport

energy use is too high. Pollution from transportation is excessive. Competitive

modes, including mass transit, bicycles, and walking, suffer from an inefficiently

low demand.

Perhaps the most pernicious effect of understated transport cost, however, is its

effect on land use. Low transport cost encourages dispersed settlement patterns.

Residences can be located far from work and shopping because the costs of travel are

so low. Unfortunately, this pattern of dispersal creates a path dependence that is

hard to reverse. Once settlement patterns are dispersed, it is difficult to justify high-

volume transportation alternatives (such as trains or buses). Both need high-density

travel corridors in order to generate the ridership necessary to pay the high fixed

cost associated with building and running these systems. With dispersed settlement

patterns, sufficiently high travel densities are difficult, if not impossible, to generate.

Policy toward Mobile Sources

History

Concern about mobile-source pollution originated in Southern California in the

early 1950s following a path-breaking study by Dr. A. J. Haagen-Smit of the

California Institute of Technology. The study by Dr. Haagen-Smit identified

motor vehicle emissions as a key culprit in forming the photochemical smog for

which Southern California was becoming infamous.

In the United States, the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1965 set national

standards for hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide emissions from automobiles to

take effect during 1968. Interestingly, the impetus for this act came not only from the

scientific data on the effects of automobile pollution, but also from the automobile

2

2007 Annual Urban Mobility Report, Texas Transportation Institute. http://mobility.tamu.edu/ums/ as

cited in “Using Pricing to Reduce Congestion” (2009), Congressional Budget Office.

447Policy toward Mobile Sources

industry itself. The industry saw uniform federal standards as a way to avoid a

situation in which every state passed its own unique set of emissions standards,

something the auto industry wanted to avoid. This pressure was successful in that the

law prohibits all states, except California, from setting their own standards.

By 1970 the slow progress being made on air pollution control in general and

automobile pollution in particular created the political will to act. In a “get tough”

mood as it developed the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1970, Congress required

new emissions standards that would reduce emissions by 90 percent below their

uncontrolled levels. This reduction was to have been achieved by 1975 for

hydrocarbon and carbon monoxide emissions and by 1976 for nitrogen dioxide.

It was generally agreed at the time the Act was passed that the technology to meet

the standards did not exist. By passing this tough act, Congress hoped to force the

development of an appropriate technology.

It did not work out that way. The following years ushered in a series of deadline

extensions. In 1972 the automobile manufacturers requested a one-year delay in

the implementation of the standards. The administrator of the EPA denied the

request and was taken to court. At the conclusion of the litigation in April 1973, the

administrator granted a one-year delay in the 1975 deadline for the hydrocarbon

and carbon monoxide standards. Subsequently, in July 1973, a one-year delay was

granted for nitrogen oxides as well.

3

That was not the last deferred deadline.

Structure of the U.S. Approach

The overall design of the U.S. approach to mobile-source air pollution has served

as a model for mobile-source control in many other countries (particularly in

Europe). We therefore examine this approach in some detail.

The U.S. approach represents a blend of controlling emissions at the point of

manufacture with controlling emissions from vehicles in use. New car emissions

standards are administered through a certification program and an associated

enforcement program.

Certification Program. The certification program tests prototypes of car models

for conformity to federal standards. During the test, a prototype vehicle from each

engine family is driven 50,000 miles on a test track or a dynamometer, following a

mandated, strict pattern of fast and slow driving, idling, and hot- and cold-starts.

The manufacturers run the tests and record emissions levels at 5,000-mile

intervals. If the vehicle satisfies the standards over the entire 50,000 miles, it passes

the deterioration portion of the certification test.

The second step in the certification process is to apply less demanding (and less

expensive) tests to three additional prototypes in the same engine family. Emissions

readings are taken at the 0 and 4,000-mile points and then, using the deterioration

3

The only legal basis for granting an extension was technological infeasibility. Only shortly before the

extension was granted, the Japanese Honda CVCC engine was certified as meeting the original

standards. It is interesting to speculate on what the outcome would have been if the company meeting

the standards was American, rather than Japanese.

448 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

rate established in the first portion of the test, are projected to the 50,000-mile

point. If those projected emissions levels meet the standards, then that engine

family is given a certificate of conformity. Only engine families with a certificate of

conformity are allowed to be sold.

Associated Enforcement Program. The certification program is complemented

by an associated enforcement program that contains assembly-line testing, as well

as recall and antitampering procedures and warranty provisions. To ensure that the

prototype vehicles are representative, the EPA tests a statistically representative

sample of assembly-line vehicles. If these tests reveal that more than 40 percent

of the cars do not conform with federal standards, the certificate may be suspended

or revoked.

The EPA has also been given the power to require manufacturers to recall and

remedy manufacturing defects that cause emissions to exceed federal standards.

If the EPA uncovers a defect, it usually requests the manufacturer to recall vehicles

for corrective action. If the manufacturer refuses, the EPA can order a recall.

The Clean Air Act also requires two separate types of warranty provisions.

These warranty provisions are designed to ensure that a manufacturer will have an

incentive to produce a vehicle that, if properly maintained, will meet emissions

standards over its useful life. The first of these provisions requires the vehicle to

be free of defects that could cause the vehicle to fail to meet the standards. Any

defects discovered by consumers would be fixed at the manufacturer’s expense

under this provision.

The second warranty provision requires the manufacturer to bring any car that

fails an inspection and maintenance test (described below) during its first

24 months or 24,000 miles (whichever occurs first) into conformance with the

standards. After the 24 months or 24,000 miles, the warranty is limited solely to the

replacement of devices specifically designed for emissions control, such as catalytic

converters. This further protection lasts 60 months.

The earliest control devices used to control pollution had two characteristics

that rendered them susceptible to tampering: they adversely affected vehicle

performance, and they were relatively easy to circumvent. As a result, the Clean Air

Act Amendments of 1970 prohibited anyone from tampering with an emissions

control system prior to the sale of an automobile, but, curiously, prohibited only

dealers and manufacturers from tampering after the sale. The 1977 amendments

extended the coverage of the postsale tampering prohibition to motor vehicle

repair facilities and fleet operators.

Local Responsibilities. The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1977 recognized the

existence of nonattainment areas. Special requirements were placed on control

authorities to bring nonattainment areas into attainment. Many of the nonattainment

areas received that designation for pollutants generated by mobile sources, so local

authorities in those areas were required to take further actions to reduce emissions

from mobile sources.

449Policy toward Mobile Sources

Measures that local authorities are authorized to use include requiring new cars

registered in that area to satisfy the more stringent California standard (with EPA

approval) and the development of comprehensive transportation plans. These plans

could include measures such as on-street parking controls, road charges, and

measures to reduce the number of vehicle miles traveled.

In nonattainment regions that could not meet the primary standard for

photochemical oxidants, carbon monoxide, or both by December 31, 1982, control

authorities could delay attainments until December 31, 1987, provided they agreed

to a number of additional restrictions. For the purposes of this chapter, the most

important of these is the requirement that each region gaining this extension must

establish a vehicle inspection and maintenance (I&M) program for emissions.

The objective of the I&M program is to identify vehicles that are violating

the standards and to bring them into compliance, to deter tampering, and to

encourage regular routine maintenance. Because the federal test procedure used in

the certification process is much too expensive to use on a large number of vehicles,

shorter, less expensive tests were developed specifically for the I&M programs.

Because of the expense and questionable effectiveness of these programs, they are

one of the most controversial components of the policy package used to control

mobile-source emissions.

Lead. Section 211 of the U.S. Clean Air Act provides the EPA with the authority

to regulate lead and any other fuel additives used in gasoline. Under this provision

gasoline suppliers were required to make unleaded gasoline available. By ensuring

the availability of unleaded gasoline, this regulation sought to reduce the amount of

airborne lead, as well as to protect the effectiveness of the catalytic converter, which

was poisoned by lead.

4

On March 7, 1985, the EPA issued regulations imposing strict new standards on

the allowable lead content in refined gasoline. The primary phaseout of lead was

completed by 1986. These actions followed a highly publicized series of medical

research findings on the severe health and developmental consequences, particularly

to small children, of even low levels of atmospheric lead. The actions worked. A 1994

study showed that U.S. blood-lead levels declined 78 percent from 1978 to 1991.

CAFE Standards

The Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) program, established in 1975, was

designed to reduce American dependence on foreign oil by producing more

fuel-efficient vehicles. Although it is not an emissions control program, fuel

efficiency does affect emissions.

The program requires each automaker to meet government-set miles-per-gallon

targets (CAFE standards) for all its car and light truck fleets sold in the United

States each year. The unique feature is that the standard is a fleet average, not a

4

Three tanks of leaded gas used in a car equipped with a catalytic converter would produce a 50 percent

reduction in the effectiveness of the catalytic converter.

450 Chapter 17 Mobile-Source Air Pollution

standard for each vehicle. As a result, automakers can sell some low-mileage vehicles

as long as they sell enough high-mileage vehicles to raise the average to the

standard. The CAFE standards took effect in 1978, mandating a fleet average of

18 miles per gallon (mpg) for automobiles. The standard increased each year until

1985 when it reached 27.5 mpg. The standards have been controversial. Most

observers believe that the CAFE standards did, in fact, reduce oil imports. During

the 1977–1986 period, oil imports fell from 47 to 27 percent of total oil

consumption. A more fundamental debate about CAFE standards involves its

effectiveness relative to fuel taxes (see Debate 17.1).

CAFE standards, however, have had their share of problems. When Congress

instituted the CAFE standards, light trucks were allowed to meet a lower fuel-

economy standard because they constituted only 20 percent of the vehicle market

and were used primarily as work vehicles. Light truck standards were set at 17.2 mpg

for the 1979 model year and went up to 20.7 mpg in 1996 (combined two-wheel and

four-wheel drive). With the burgeoning popularity of SUVs, which are counted as

light trucks, trucks now comprise nearly half of the market. In addition, intense

lobbying by the auto industry resulted in an inability of Congress to raise the

standards from 1985 until 2004. As a result of the lower standards for trucks and

SUVs, the absence of any offsetting increase in the fuel tax, and the increasing

importance of trucks and SUVs in the fleet of on-road vehicles, the average miles

per gallon for all vehicles declined, rather than improved. In 2005 the standard for

light trucks saw its first increase since 1996 to 21 mpg.

The standards for all types of vehicles have recently continued this upward

trend. Standards for model year 2011 rose to 27.3 miles per gallon. According

to Department of Transportation’s National Highway Transportation Safety

Administration (NHTSA), this increase was expected to save 887 million gallons

of fuel and reduce CO

2

emissions by 8.3 million metric tons.

In 2010, new rules were announced for both fuel efficiency and greenhouse gas

emissions. These rules will cover the 2012–2016 model years and the CAFE

standard has been set to reach 34.1 miles per gallon by 2016. Medium- and

heavy-duty trucks were also subject to new rules. The U.S. EPA and the National

Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) calculated benefits and costs

of the proposed program for medium- and heavy-duty trucks. Using a social cost

of carbon of $22/ton and a 3 percent discount rate, they find costs to the industry

of $7.7 billion and societal benefits of $49 billion, for a total net benefit of

approximately $41 billion.

5

Currently, the penalty for failing to meet CAFE standards is “$5.50 per tenth of a

MPG under the target value times the total volume of those vehicles manufactured

for a given model year” (Department of Transportation, www.nhsta.dot.gov).

Manufacturers have paid more than $590 million in CAFE fines since 1983.

European manufacturers have consistently paid CAFE penalties ($1 million to $20

million annually), while Asian and U.S. manufacturers have rarely paid a penalty.

5

http://www.nhtsa.gov/staticfiles/rulemaking/pdf/cafe/CAFE_2014-18_Trucks_FactSheet-v1.pdf,

October 2010.