Tietenberg Tom, Lewis Lynne. Environmental & Natural Resource Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

371Cost-Effective Policies for Uniformly Mixed Fund Pollutants

to a cost-effective allocation, total costs would increase if both sources were forced

to clean up the same amount.

When emissions standards are the policy of choice, there is no reason to believe that

the authority will assign the responsibility for emissions reduction in a cost-minimizing

way. This is probably not surprising. Who would have believed otherwise?

Surprisingly enough, however, some policy instruments do allow the authority

to allocate the emissions reduction in a cost-effective manner even when it has no

information on the magnitude of control costs. These policy approaches rely on

economic incentives to produce the desired outcome. The two most common

approaches are known as emissions charges and emissions trading.

Emissions Charges. An emissions charge is a fee, collected by the government, levied

on each unit of pollutant emitted into the air or water. The total payment any source

would make to the government could be found by multiplying the fee times the

amount of pollution emitted. Emissions charges reduce pollution because paying the

fees costs the firm money. To save money, the source seeks ways to reduce its pollution.

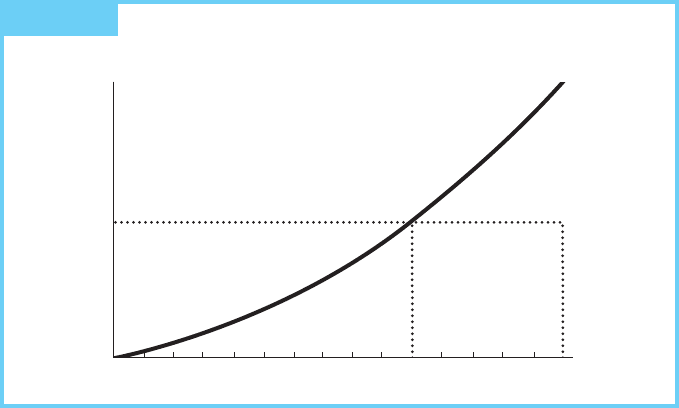

How much pollution control would the firm choose? A profit-maximizing firm

would control, rather than emit, pollution whenever it proved cheaper to do so. We

can illustrate the firm’s decision with Figure 14.4. The level of uncontrolled emission

is 15 units and the emissions charge is T. Thus, if the firm were to decide against

controlling any emissions, it would have to pay T times 15, represented by area 0TBC.

Is this the best the firm can do? Obviously not, since it can control some

pollution at a lower cost than paying the emissions charge. It would pay the firm to

reduce emissions until the marginal cost of reduction is equal to the emissions

charge. The firm would minimize its cost by choosing to clean up ten units of

pollution and to emit five units. At this allocation the firm would pay control

costs equal to area 0AD and total emissions charge payments equal to area ABCD

FIGURE 14.4 Cost-Minimizing Control of Pollution with an Emissions Charge

Cost

(in dollars)

Units of

Emissions

Controlled

MC

1

T

A

B

CD

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13

01410 15

372 Economics of Pollution Control: An Overview

for a total cost of 0ABC. This is clearly less than 0TBC, the amount the firm would

pay if it chose not to clean up any pollution.

Let’s carry this one step further. Suppose that we levied the same emissions

charge on both sources discussed in Figure 14.3. Each source would then control

its emissions until its marginal control cost equaled the emissions charge. (Faced

with an emissions charge T, the second source would clean up five units.) Since they

both face the same emissions charge, they will independently choose levels of control

consistent with equal marginal control costs. This is precisely the condition that

yields a cost-minimizing allocation.

This is a remarkable finding. We have shown that as long as the control authority

imposes the same emissions charge on all sources, the resulting incentives are

automatically compatible with minimizing the costs of achieving that level of control.

This is true in spite of the fact that the control authority may not have sufficient

knowledge of control costs.

However, we have not yet dealt with the issue of how the appropriate level of the

emissions charge is determined. Each level of a charge will result in some level of

emissions reduction. Furthermore, as long as each firm minimizes its own costs, the

responsibility for meeting that reduction will be allocated in a manner that minimizes

control costs for all firms. How high should the charge be set to ensure that the

resulting emissions reduction is the desired level of emissions reduction?

Without having the requisite information on control costs, the control authority

cannot establish the correct tax rate on the first try. It is possible, however, to develop an

iterative, trial-and-error process to find the appropriate charge rate. This process is

initiated by choosing an arbitrary charge rate and observing the amount of reduction

that occurs when that charge is imposed. If the observed reduction is larger than

desired, it means the charge should be lowered; if the reduction is smaller, the charge

should be raised. The new reduction that results from the adjusted charge can then be

observed and compared with the desired reduction. Further adjustments in the charge

can be made as needed. This process can be repeated until the actual and desired

reductions are equal. At that point the correct emissions charge would have been found.

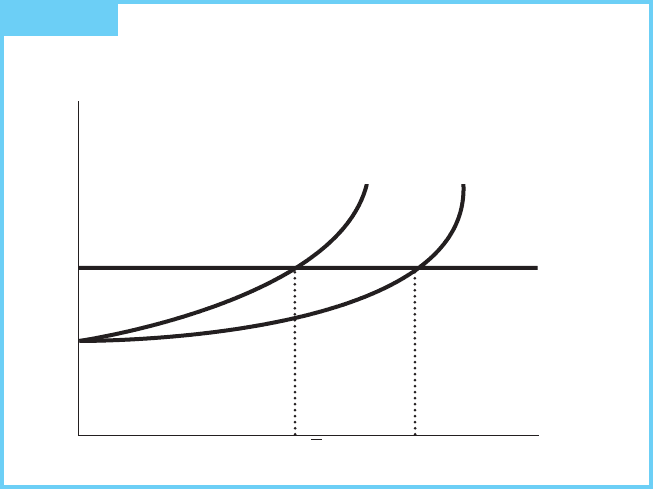

The charge system not only causes cost-minimizing sources to choose a cost-

effective allocation of the control responsibility, it also stimulates the development

of newer, cheaper means of controlling emissions, as well as promoting technolog-

ical progress. This is illustrated in Figure 14.5.

The reason for this is rather straightforward. Control authorities base the

emissions standards on specific technologies. As new technologies are discovered

by the control authority, the standards are tightened. These stricter standards force

firms to bear higher costs. Therefore, with emissions standards, firms have an

incentive to hide technological changes from the control authority.

With an emissions charge system, the firm saves money by adopting cheaper

new technologies. As long as the firm can reduce its pollution at a marginal cost

lower than T, it pays to adopt the new technology. In Figure 14.5 the firm saves A

and B by adopting the new technology and voluntarily increases its emissions

reduction from Q

0

to Q

1

.

With an emissions charge, the minimum cost allocation of meeting a predetermined

emissions reduction can be found by a control authority even when it has insufficient

373Cost-Effective Policies for Uniformly Mixed Fund Pollutants

FIGURE 14.5 Cost Savings from Technological Change: Charges versus

Standards

information on control costs. An emissions charge also stimulates technological

advances in emissions reduction. Unfortunately, the process for finding the appropriate

rate takes some experimenting. During the trial-and-error period of finding the appro-

priate rate, sources would be faced with a volatile emissions charge. Changing emissions

charges would make planning for the future difficult. Investments that would make

sense under a high emissions charge might not make sense when it falls. From either a

policy-maker’s or business manager’s perspective, this process leaves much to be desired.

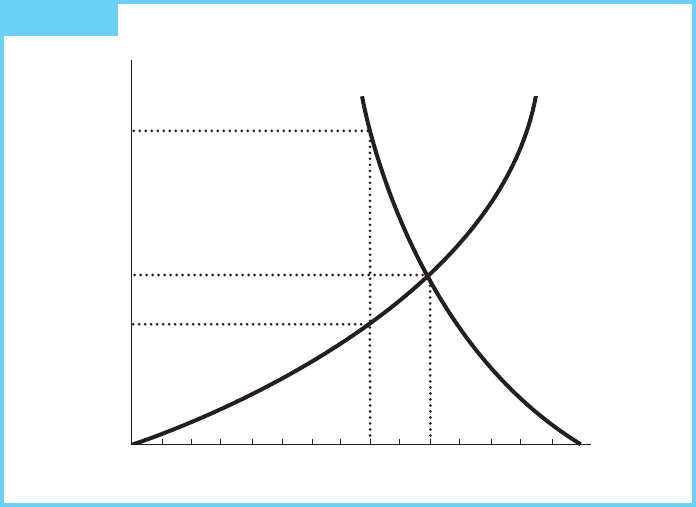

Cap-and-Trade. Is it possible for the control authority to find the cost-minimizing

allocation without going through a trial-and-error process? It is possible if cap-

and-trade is the chosen policy. Under this system, all sources face a limit on their

emissions and they are allocated (or sold) allowances to emit. Each allowance

authorizes a specific amount of emissions (commonly 1 ton). The control authority

issues exactly the number of allowances needed to produce the desired emissions

level. These can be distributed among the firms either by auctioning them off to the

highest bidder or by granting them directly to firms free of charge (an allocation

referred to as “gifting”). However they are acquired, the allowances are freely

transferable; they can be bought and sold. Firms emitting more than their holdings

would buy additional allowances from firms who are emitting less than authorized.

Any emissions by a source in excess of those allowed by its allowance holdings at the

end of the year would cause the source to face severe monetary sanctions.

Why this system automatically leads to a cost-effective allocation can be seen in

Figure 14.6, which treats the same set of circumstances as in Figure 14.3. Consider

first the gifting alternative. Suppose that the first source was allocated seven

$/Unit

Quantity of

Emissions

Reduced

MC

0

MC

1

B

A

T

0

Q

1

Q

0

= Q

374 Economics of Pollution Control: An Overview

FIGURE 14.6 Cost-Effectiveness and Emissions Trading

allowances (each allowance corresponds to one emission unit). Because it has

15 units of uncontrolled emissions, this would mean it must control eight units.

Similarly, suppose that the second source was granted the remaining eight

allowances, meaning that it would have to clean up seven units. Notice that both

firms have an incentive to trade. The marginal cost of control for the second source

(C) is substantially higher than that for the first (A). The second source could lower

its cost if it could buy an allowance from the first source at a price lower than C.

Meanwhile, the first source would be better off if it could sell an allowance for a

price higher than A. Because C is greater than A, grounds for trade certainly exist.

A transfer of allowances would take place until the first source had only five

allowances left (and controlled ten units), while the second source had ten allowances

(and controlled five units). At this point, the allowance price would equal B, because

that is the marginal value of that allowance to both sources, and neither source would

have any incentive to trade further. The allowance market would be in equilibrium.

Notice that the market equilibrium for an emission-allowance system is the

cost-effective allocation! Simply by issuing the appropriate number of allowances

(15) and letting the market do the rest, the control authority can achieve a cost-

effective allocation without having even the slightest knowledge about control

costs. This system allows the government to meet its policy objective, while

allowing greater flexibility in how that objective is met.

How would this equilibrium change if the allowances were auctioned off?

Interestingly, it wouldn’t; both allocation methods lead to the same result. With an

auction, the allowance price that clears demand and supply is B, and we have

already demonstrated that B supports a cost-effective equilibrium.

Marginal Cost

(dollars

per unit)

Quantity of

Emissions

Reduced

MC

1

MC

2

B

A

C

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 11 12 13

15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Source 2

0Source 1 151410

375Cost-Effective Policies for Uniformly Mixed Fund Pollutants

DEBATE

14.1

Should Developing Countries Rely on

Market-Based Instruments to Control Pollution?

Since the case for using market-based instruments seems so strong in princi-

ple, some observers, most prominently the World Bank (2000), have suggested

that developing countries should capitalize on the experience of the industrial-

ized countries to move directly to market-based instruments to control pollu-

tion. The desirability of this strategy is seen as flowing from the level of poverty

in developing countries; abating pollution in the least expensive manner would

seem especially important to poorer nations. Furthermore, since developing

countries are frequently also starved for revenue, revenue-generating

instruments (such as emissions charges or auctioned allowances) would seem

especially useful. Proponents also point out that a number of developing

countries already use market-based instruments.

Another school of thought (e.g., Russell and Vaughan, 2003) suggests that

the differences in infrastructure between the developing and industrialized

countries make the transfer of lessons from one context to another fraught

with peril. To illustrate their more general point, they note that the effective-

ness of market-based instruments presumes an effective monitoring and

enforcement system, something that is frequently not present in developing

countries. In its absence, the superiority of market-based instruments is much

less obvious.

Some middle ground is clearly emerging. Russell and Vaughan do not argue that

market-based instruments should never be used in developing countries, but rather

that they may not be as universally appropriate as the most enthusiastic proponents

seem to suggest. They see themselves as telling a cautionary tale. And proponents are

certainly beginning to see the crucial importance of infrastructure. Recognizing that

some developing countries may be much better suited (by virtue of their infrastructure)

to implement market-based systems than others, proponents are beginning to see

capacity building as a logical prior step for those countries that need it.

For market-based instruments, as well as for other aspects of life, if it looks

too good to be true, it probably is.

Source

: World Bank.

Greening Industry

:

New Roles for Communities, Markets and Governments

(Washington, DC: World Bank and Oxford University Press, 2000); and Clifford S. Russell and William J.

Vaughan. “The Choice of Pollution Control Policy Instruments in Developing Countries: Arguments,

Evidence and Suggestions,” in Henk Folmer and Tom Tietenberg, eds.

The International Yearbook of

Environmental and Resource Economics 2003/2004

(Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, 2003): 331–371.

The incentives created by this system ensure that sources use this flexibility to

achieve the objective at the lowest possible cost. As we shall see in the next two

chapters, this remarkable property has been responsible for the prominence of this type

of approach in current attempts to reform the regulatory process.

How far can the reforms go? Can developing countries use the experience of the

industrialized countries to move directly into using these market-based instruments to

control pollution?

As Debate 14.1 points out, that may be easier said than done.

376 Economics of Pollution Control: An Overview

Cost-Effective Policies for Nonuniformly

Mixed Surface Pollutants

The problem becomes more complicated when dealing with nonuniformly mixed

surface pollutants rather than uniformly mixed pollutants. For these pollutants, the

policy must be concerned not only with the weight of emissions entering the

atmosphere, but also with the location and timing of emissions. For nonuniformly

mixed pollutants, it is the concentration in the air, soil, or water that counts. The

concentration is measured as the amount of pollutant found in a given volume of

air, soil, or water at a given location and at a given point in time.

It is easy to see why pollutant concentrations are sensitive to the location of

emissions. Suppose that three emissions sources are clustered and emit the same

amount as three distant but otherwise-identical sources. The emissions from the

clustered sources generally cause higher pollution concentrations because they are all

entering the same volume of air or water. Because the two sets of emissions do not

share a common receiving volume, those from the dispersed sources result in lower

concentrations. This is the main reason why cities generally face more severe pollu-

tion problems than do rural areas; urban sources tend to be more densely clustered.

The timing of emissions can also matter in two rather different senses. First,

when pollutants are emitted in bursts rather than distributed over time they can

result in higher concentrations. Second, as illustrated in Example 14.2, the time of

year in which some pollutants are emitted can mattter.

Since the damage caused by nonuniformly mixed surface pollutants is related to

their concentration levels in the air, soil, or water, it is natural that our search for

cost-effective policies for controlling these pollutants focuses on the attainment of

ambient standards. Ambient standards are legal ceilings placed on the concentration

level of specified pollutants in the air, soil, or water. They represent the target

concentration levels that are not to be exceeded. A cost-effective policy results in the

lowest cost allocation of control responsibility consistent with ensuring that the

predetermined ambient standards are met at specified locations called receptor sites.

The Single-Receptor Case

We can begin the analysis by considering a simple case in which we desire to con-

trol pollution at one, and only one, receptor location. We know that all units of

emissions from sources do not have the same impact on pollution measured at that

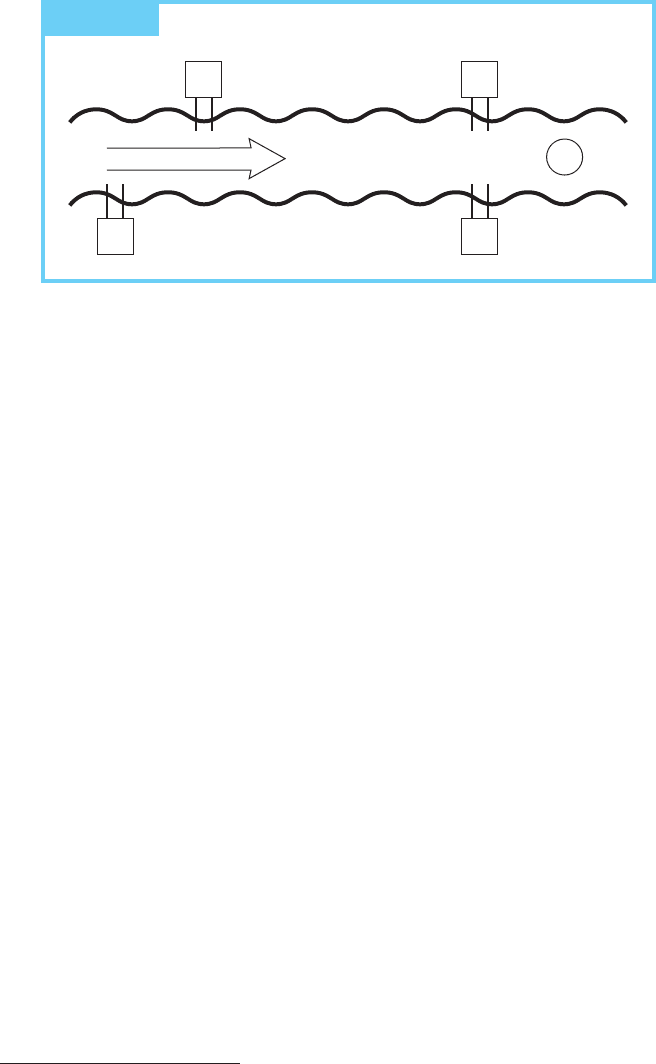

receptor. Consider, for example, Figure 14.7.

Suppose that we allow each of the four sources individually, at different points in

time, to inject ten units of emission into the stream. Suppose further that we

measured the pollutant concentration resulting from each of these injections at

receptor R. In general, we would find that the emissions from A or B would cause a

larger rise in the recorded concentration than would those from C and D, even

though the same amount was emitted from each source. The reason for this is that

the emissions from C and D would be substantially diluted by the time they arrived

at R, while those from A and B would arrive in a more concentrated form.

377Cost-Effective Policies for Nonuniformly Mixed Surface Pollutants

Emissions Trading in Action: The NO

x

Budget

Program

NO

x

emissions react with volatile organic compounds in the presence of

sunlight to form smog (ozone), a pollutant that crosses state boundaries.

Recognizing the potential for transboundary externalities to arise in this

circumstance, an Ozone Transport Commission (OTC) was set up by the 1990

Clean Air Act Amendments to facilitate interstate cooperation for controlling

NO

x

emissions in the Northeast. These OTC states set up an emissions-trading

policy in 1999, which has evolved to become the more inclusive NO

x

Budget

Trading Program.

The NO

x

Budget Trading Program (NBTP) seeks to reduce emissions of nitro-

gen oxides (NO

x

) from power plants and other large combustion sources in the

eastern United States using emissions trading. Twenty-one states and the District

of Columbia are participating or will participate in the future and nearly 2,600

affected units are operating in the NBTP states.

Because ground-level ozone is highest when sunlight is most intense, the

warm summer months (May 1 to September 30) are typically referred to as the

“ozone season.” The NBTP establishes an ozone season NO

x

emissions

budget, which caps emissions in each participating state from May 1 to

September 30. Whereas most emissions-trading programs focus on reducing

annual emissions, this program, recognizing the seasonal timing of ozone

formation in the Northeast, focuses only on those emissions that directly

contribute to ozone formation.

Under this program, participating states allocate allowances (each authorizing

1 ton of NO

x

emissions) to individual power plants and other combustion sources

within their jurisdiction such that the number of allowances is compatible with

the state cap. At the end of the year, the individual regulated units have to turn in

enough allowances to cover their emissions during the ozone season. If the level

of emissions authorized by the allowances is lower than actual emissions, regu-

lated units have to buy more allowances from some other covered unit that is

willing to sell. Firms that do not have sufficient allowances (allocated plus

acquired) to cover their emissions are penalized (specifically EPA deducts 3 tons

worth of allowances from the following year’s allocation for each ton the regu-

lated unit is over).

The program has apparently been effective in reducing emissions. According to

EPA reports, NBTP ozone season NO

x

emissions in 2005 were 57 percent lower

than in 2000 (before the implementation of the NBTP) and 72 percent lower than

in 1990 (before the implementation of the Clean Air Act Amendments).

Source

: http://www.epa.gov/airmarkets/progsregs/nox/sip.html.

EXAMPLE

14.2

Since emissions are what can be controlled, but the concentrations at R are the

policy target, our first task must be to relate the two. This can be accomplished by

using a transfer coefficient. A transfer coefficient (a

i

) captures the constant

amount the concentration at the receptor will rise if source i emits one more unit of

378 Economics of Pollution Control: An Overview

Stream Flow

R

C

D

B

A

FIGURE 14.7 Effect of Location on Local Pollutant Concentration

pollution. Using this definition and the knowledge that the a

i

s are constant, we can

relate the concentration level at R to emissions from all sources:

(1)

where

K

R

⫽ concentration at the receptor

E

i

⫽ emissions level of the ith source

I ⫽ total number of sources in the region

B ⫽ background concentration level (resulting from natural sources or sources

outside the control region)

We are now in a position to define the cost-effective allocation of responsibility. A

numerical example involving two sources is presented in Table 14.1. In this example, the

two sources are assumed to have the same marginal cost curves for cleaning up emis-

sions. This assumption is reflected in the fact that the first two corresponding columns

of the table for each of the two sources are identical.

7

The main difference between the

two sources is their location vis-à-vis the receptor. The first source is closer to the recep-

tor, so it has a larger transfer coefficient than the second (1.0 as opposed to 0.5).

The objective is to meet a given concentration target at minimum cost. Column

3 of the table translates emissions reductions into concentration reductions for

each source, while column 4 records the marginal cost of each unit of concentra-

tion reduced. The former is merely the emissions reduction times the transfer

coefficient, while the latter is the marginal cost of the emissions reduction divided

by the transfer coefficient (which translates the marginal cost of emissions reduction

into a marginal cost of concentration reduction).

Suppose the concentration at the receptor has to be reduced by 7.5 units in order

to comply with the ambient standard. The cost-effective allocation would be

achieved when the marginal costs of concentration reduction (not emissions reduction)

are equalized for all sources. In Table 14.1, this occurs when the first source reduces

K

R

=

a

I

i= 1

a

i

E

i

+ B

7

This assumption has no bearing on the results we shall achieve. It serves mainly to illustrate the role

location plays on eliminating control-cost difference as a factor.

379Cost-Effective Policies for Nonuniformly Mixed Surface Pollutants

TABLE 14.1 Cost-Effectiveness for Nonuniformly Mixed Pollutants: A Hypothetical Example

Source 1 (

a

1

⫽ 1.0)

Emissions Units

Reduced

Marginal Cost of Emissions

Reduction (dollars per unit)

Concentration

Units Reduced

1

Marginal Cost of

Concentration Reduction

(dollars per unit)

2

1

11.01

2 2 2.0 2

3 3 3.0 3

4 4 4.0 4

5 5 5.0 5

6 6 6.0 6

777.07

Source 2 (

a

2

⫽ 0.5)

1 1 0.5 2

221.04

331.56

4 4 2.0 8

5 5 2.5 10

6 6 3.0 12

7 7 3.5 14

1

Computed by multiplying the emissions reduction (column 1) by the transfer coefficient (

a

i

).

2

Computed by dividing the marginal cost of emissions reduction (column 2) by the transfer coefficient (

a

i

).

six units of emissions (and six units of concentration) and the second source reduces

three units of emissions (and 1.5 units of concentration). At this allocation the

marginal cost of concentration reduction is equal to $6 for both sources. By adding

all marginal costs for each unit reduced, we calculate the total variable cost of this

allocation to be $27. From the definition of cost-effectiveness, no other allocation

resulting in 7.5 units of concentration reduction would be cheaper.

Policy Approaches for Nonuniformly Mixed Pollutants. This framework can

now be used to evaluate various policy approaches that the control authority might

use. We begin with the ambient charge, the charge used to produce a cost-effective

allocation of a nonuniformly mixed pollutant. This charge takes the form:

(2)

where t

i

is the per-unit charge paid by the ith source on each unit emitted, a

i

is the

ith source’s transfer coefficient, and F is the marginal cost of a unit of concentration

reduction, which is the same for all sources. In our example, F is $6, so the first

t

i

= a

i

F

380 Economics of Pollution Control: An Overview

source would pay a per-unit emissions charge of $6, while the second source would

pay $3. Note that sources will, in general, pay different charges when the objective is to meet

an ambient standard at minimum cost because their transfer coefficients differ. This

contrasts with the uniformly mixed pollutant case in which a cost-effective

allocation required that all sources pay the same charge.

How can the cost-effective t

i

be found by a control authority with insufficient

information on control costs? The transfer coefficients can be calculated using

knowledge of hydrology and meteorology, but what about F? Here a striking

similarity to the uniformly mixed case becomes evident. Any level of F would

yield a cost-effective allocation of control responsibility for achieving some level of

concentration reduction at the receptor. That level might not, however, be com-

patible with the ambient standard.

We could ensure compatibility by changing F in an iterative process until the

desired concentration is achieved. If the actual pollutant concentration is below

the standard, the tax could be lowered; if it is above, the tax could be raised.

The correct level of F would be reached when the resulting pollution concentra-

tion is equal to the desired level. That equilibrium allocation would be the one that

meets the ambient standard at minimum cost.

Table 14.1 allows us to consider another issue of significance. The cost-effective

allocation of control responsibility for achieving surface-concentration targets

places a larger information burden on control authorities; they have to calculate the

transfer coefficients. What is lost if the simpler emissions charge system (where

each source faces the same charge) is used to pursue a surface-concentration target?

Can location be safely ignored?

Let’s use our numerical example to find out. In Table 14.1, a uniform emissions

charge equal to $5 would achieve the desired 7.5 units of reduction (5 from the first

source and 2.5 from the second). Yet the total variable cost of this allocation (calcu-

lated as the sum of the marginal costs) would be $30 ($15 paid by each source).

This is $3 higher than the allocation resulting from the use of ambient charge

discussed earlier. In subsequent chapters we present empirical estimates of the size

of this cost increase in actual air and water pollution situations. In general, they

show the cost increases to be large; location matters.

Table 14.1 also helps us understand why location matters. Notice that with a uni-

form emissions charge, ten units of emission are cleaned up, whereas with the ambi-

ent charge, only nine units are cleaned up. Both achieve the concentration target, but

the uniform-emissions charge results in fewer emissions. The ambient charge results

in a lower cost allocation than the emissions charge because it results in less emissions

control. Those sources having only a small effect on the recorded concentration at

the receptor location are able to control less than they would with a uniform charge.

With the ambient charge, we have the same problem that we encountered with

emissions charges in the uniformly mixed pollutant case—the cost-effective level

can be determined only by an iterative process. Can emissions trading get around

this problem when dealing with nonuniformly mixed pollutants?

It can, by designing the allowance trading system in the correct way. An ambient

allowance market (as opposed to an emissions allowance market) entitles the owner

to cause the concentration to rise at the receptor by a specified amount, rather than