Tietenberg Tom, Lewis Lynne. Environmental & Natural Resource Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further Reading

Barbier, E. B. “The Economic Determinants of Land Degradation in Developing

Countries,” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences Vol. 352 (1997):

891–899. Investigates the economic determinants of land degradation in developing

countries, focusing on rural households’ decisions to degrade (as opposed to conserve)

land resources, and the expansion of frontier agricultural activity that contributes to

forest and marginal land conversion.

Bell, K. P., K. J. Boyle, and J. Rubin. Economics of Rural Land-Use Change (Aldershot, UK:

Ashgate 2006). Presents an overview of the economics of rural land-use change; includes

theoretical and empirical work on both the determinants and consequences of this

change.

Irwin, Elena G., Kathleen P. Bell, Nancy E. Bockstael, David A. Newburn, Mark D.

Partridge, and Jun Jie Wu. “The Economics of Urban-Rural Space,” Annual Review of

Resource Economics Vol. 1 (2009): 435–459. Changing economic conditions, including

waning transportation and communication costs, technological change, rising real

incomes, and changing tastes for natural amenities, have led to new forms of urban–rural

interdependence. This paper reviews the literature on urban land-use patterns, highlight-

ing research on environmental impacts and the efficacy of growth controls and land

conservation programs that seek to manage this growth.

Johnston, R. J., and S. K. Swallow, eds. Economics and Contemporary Land Use Policy

(Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, Inc. 2006). Explores the causes and

consequences of rapidly accelerating land conversions in urban-fringe areas, as well as

implications for effective policy responses.

McConnell, Virginia, and Margaret Walls. “U.S. Experience with Transferable Development

Rights,” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy Vol. 3, No. 2 (2009): 288–303.

This article summarizes the key elements in the design of TDR programs and reviews a

number of existing markets to identify which have performed well and which have not.

Additional References and Historically Significant References are available on this book’s

Companion Website:http://www.pearsonhighered.com/tietenberg/.

261Further Reading

262

11

11

Reproducible Private Property

Resources: Agriculture and

Food Security

We, the Heads of State and Government, Ministers and Representatives of

181 countries and the European Community, . . . reaffirm the conclusions

of the World Food Summit in 1996 . . . and the objective . . . of achieving

food security for all through an ongoing effort to eradicate hunger in all

countries, with an immediate view to reducing by half the number of

undernourished people by no later than 2015, as well as our commitment

to achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). . . .

. . . We firmly resolve to use all means to alleviate the suffering caused by

the current crisis, to stimulate food production and to increase investment

in agriculture, to address obstacles to food access and to use the planet’s

resources sustainably, for present and future generations. We commit to

eliminating hunger and to securing food for all today and tomorrow.

—World Food Summit (Rome, June 2008)

Introduction

In 1974, the World Food Conference set a goal of eradication of hunger, food

insecurity, and malnutrition within a decade. This goal was never met. The

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimated that

without faster progress, 680 million people would still face hunger by the year

2010 and that more than 250 million of these people would be in Sub-Saharan

Africa. Amidst growing concern about widespread undernutrition and about the

capacity of agriculture to meet future food needs, a World Food Summit was

called. Held at FAO headquarters in Rome in November 1996, the Food

Summit attracted ten thousand participants representing 185 countries and the

European community.

The Rome Declaration on World Food Security, which came out of the Food

Summit, set a target of reducing by half the number of undernourished people by

2015. In June 2002, at a subsequent World Food Summit, delegates reiterated their

pledge to meet this goal. In 2008, as the opening quote to this chapter notes,

delegates reaffirmed this pledge. How close are we to meeting this goal?

263Global Scarcity

The evidence is not encouraging. In 2010, some 925 million people were classified

as hungry or undernourished, the majority of whom live in Asia or Sub-Saharan

Africa. Many of these people also suffer from chronic hunger and malnutrition. Even

in the United States, approximately one in ten households (or 33.6 million people)

experience hunger or the risk of hunger (Nord et al., 2002). According to the Food

and Agriculture Organization, the total amount of available food is not the problem;

the world produces plenty of food to feed everyone. World agriculture produces 17

percent more calories per person today than 30 years ago. This increase is despite the

fact that population has increased by 70 percent over the same time period (FAO,

1998, 2002). If this is the case, why are so many people hungry?

While the world produces enough food, many nations, especially in Sub-Saharan

Africa currently do not produce enough food to feed their populations and high

rates of poverty make it difficult for them to afford to import enough food products

to make up the gap. The people have neither enough land to grow food, nor enough

income to buy it.

Cereal grain, the world’s chief supply of food, is a renewable private proprety

resource that, if managed effectively, could be sustained as long as we receive energy

from the sun. Are current agricultural practices sustainable? Are they efficient?

Because land is typically not a free-access resource, farmers have an incentive to

invest in irrigation and other means of increasing yield because they can appropriate

the additional revenues generated. On the surface, a flaw in the market process is

not apparent. We must dig deeper to uncover the sources of the problem.

In this chapter, we shall explore the validity of three common hypotheses used to

explain widespread malnourishment: (1) a persistent global scarcity of food; (2) a

maldistribution of that food both among nations and within nations that arises

from poverty, affordability, and other sources; and (3) temporary shortages caused

by weather or other natural causes. These hypotheses are not mutually exclusive;

they could all be valid sources of a portion of the problem. As we shall see, it is

important to distinguish among these sources and assess their relative importance

because each implies a different policy approach.

Global Scarcity

To some, this onset of a food crisis suggests a need for dramatic changes in the

relationship between the agricultural surplus nations and other nations. Garrett

Hardin (1974), a human ecologist, has suggested the situation is so desperate that

our conventional ethics, which involve sharing the available resources, are not only

insufficient, but are also counterproductive. He argued that we must replace these

dated notions of sharing with more stern “lifeboat ethics.”

The allegory he invokes envisions a lifeboat adrift in the sea that can safely hold

50 or, at most, 60 persons. Hundreds of other persons are swimming about,

clamoring to get into the lifeboat, their only chance for survival. Hardin suggests

that if passengers in the boat were to follow conventional ethics and allow swimmers

into the boat, it would eventually sink, taking everyone to the bottom of the sea.

264 Chapter 11 Reproducible Private Proprety Resources: Agriculture and Food Security

In contrast, he argues, lifeboat ethics would suggest a better resolution of the

dilemma; the 50 or 60 should row away, leaving the others to certain death, but

saving those fortunate enough to gain entry into the lifeboat. The implication is that

food sharing is counterproductive. It would encourage more population growth and

ultimately would cause inevitable, even more serious shortages in the future.

The existence of a global scarcity of food is the premise that underlies this view;

when famine is inevitable, sharing is merely a palliative and may, in the long run,

even become counterproductive. In the absence of global scarcity (the lifeboat has

a large enough capacity for all) then, a worldwide famine can be avoided by a

sharing of resources. How accurate is the global scarcity premise?

Formulating the Global Scarcity Hypothesis

Most authorities seem to agree that an adequate amount of food is currently being

produced. Because the evidence is limited to a single point in time, however, it

provides little sense of whether scarcity is decreasing or increasing. If we are to

identify and evaluate trends, we must develop more precise, measurable notions of

how the market allocates food.

As a renewable resource, cereal grains could be produced indefinitely, if managed

correctly. Yet two facets of the world hunger problem have to be taken into account.

First, while population growth has slowed down, it has not stopped. Therefore, it is

reasonable to expect the rising demand for food to continue. Second, the primary

input for growing food is land, and land is ultimately fixed in supply. Thus, our

analysis must explain how a market reacts in the presence of rising demand for a

renewable resource that is produced using a fixed factor of production.

A substantial and dominant proportion of the Western world’s arable land is

privately owned. Access to this land is restricted; therefore the owners have the

right to exclude others and can reap what they sow. The typical owner of farmland

has sufficient control over the resource to prevent undue depreciation, but not

enough control over the market as a whole to raise the specter of monopoly profits.

What kind of outcome could we expect from this market in the face of rising

demand and a fixed supply of land? What do we mean by scarcity and how could we

perceive its existence? The answer depends crucially on the height and slope of the

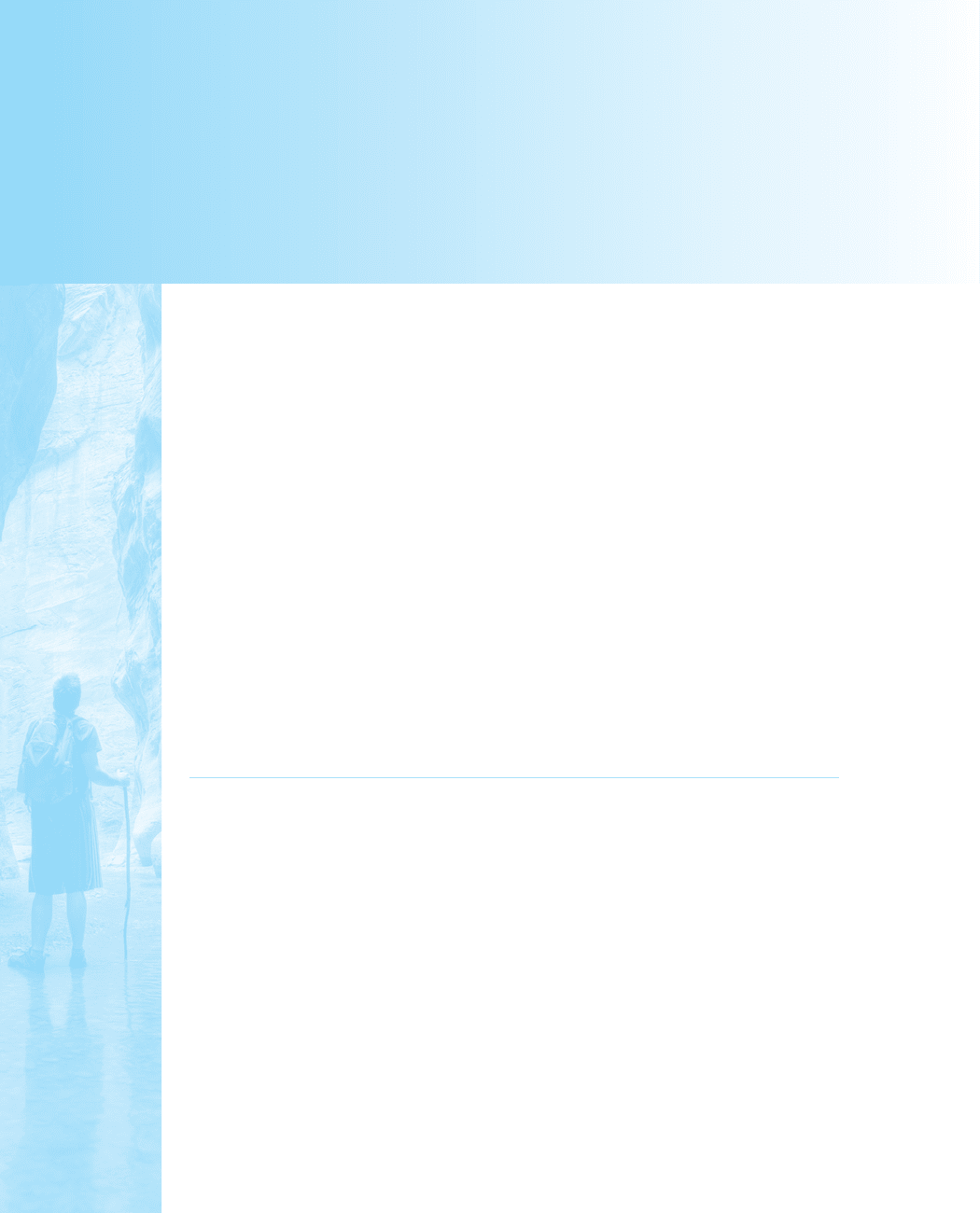

supply curve for food (see Figure 11.1).

Suppose the market is initially in equilibrium with quantity Q

0

supplied at price

P

0

. Let the passage of time be recorded as outward shifts in the demand curve.

Consider what would happen in the fifth time period. If the supply curve were S

a

,

the quantity would rise to Q

5a

with a price of P

5a

. However, if the supply curve were

S

b

, the quantity supplied would rise to Q

5b

, but price would rise to P

5b

.

This analysis sheds light on two dimensions of scarcity in the world food

market. It normally does not mean a shortage. Even under relatively adverse

supply circumstances pictured by the supply curve S

b

, the amount of food supplied

would equal the amount demanded. As prices rose, potential demand would be

choked off and additional supplies would be called forth.

265Formulating the Global Scarcity Hypothesis

FIGURE 11.1 The Market for Food

Some critics argue that the demand for food is not price sensitive. Since food is

a necessary commodity for survival, they say, its demand is inflexible and doesn’t

respond to prices. While some food is necessary, not all food fits that category. We

don’t have to gaze very long at an average vending machine in a developed country

to conclude that some food is far from a necessity.

Examples of food purchases being price responsive abound. One occurred

during the 1960s when the price of meat skyrocketed for what turned out to be a

relatively short period. It wasn’t long before hamburger substitutes made entirely

out of soybean meal, appeared in supermarkets. The result was a striking reduction

in meat consumption. This is a particularly important example because the raising

of livestock for meat in Western countries consumes an enormous amount of grain.

This evidence suggests that the balance between the direct consumption of cereal

grains and their indirect consumption through meat is affected by prices.

But enough about the demand side. What do we know of the supply side? What

factors would determine whether S

a

or S

b

is a more adequate representation of the

past and the future?

While rising prices certainly stimulate a supply response, the question is how

much? As the demand for food rises, the supply can be increased either by expanding

Price of

Food

(dollars

per unit)

Quantity

of Food

(units)

S

b

S

a

Q

5b

Q

0

Q

5a

P

5a

P

0

D

4

D

5

D

6

0

D

1

D

2

D

3

P

5b

266 Chapter 11 Reproducible Private Property Resources: Agriculture and Food Security

the amount of land under cultivation, or by increasing the yields on the land already

under cultivation for food, or some combination of the two. Historically, both

sources have been important.

Typically, the most fertile land is cultivated first. That land is then farmed more

and more intensively until it is cheaper, at the margin, to bring additional, less

fertile land into production. Because it is less fertile, the additional land is brought

into production only if the prices rise enough to make farming it profitable. Thus,

the supply curve for arable land (and hence for food, as long as land remains an

important factor of production) can be expected to slope upward.

Two forms of the global scarcity hypothesis can be tested against the available

evidence. The strong form suggests that per capita food production is declining. In

terms of Figure 11.1, the strong form of the hypothesis would imply that the slope

of the supply curve is sufficiently steep that production does not keep pace with

increases in demand brought about by population growth. If the strong form is

valid, we should witness declining per capita food production. If valid, this form

could provide some support for lifeboat ethics.

The weak form of the global scarcity hypothesis can hold even if per capita

production is increasing over time. It suggests that the supply curve is sufficiently

steeply sloped that food prices are increasing more rapidly than other prices in

general; the relative price of food is rising over time. If the weak form is valid, per

capita welfare could decline, even if production is rising. In this form the prob-

lem is related more to the cost and affordability of food than the availability of

food; as supplies of food increase, the cost of food rises relative to the cost of

other goods.

Testing the Hypotheses

Now that we have two testable hypotheses, we can assess the degree to which the

historical record supports the existence of either form of global scarcity. The

evidence for per capita production is clear. Food production has increased faster

than population in both the developed and developing countries. In other words

per capita production has increased, although the increase has been small. Thus,

at least for the recent past, we can rule out the strong form of the global scarcity

hypothesis.

How about the weak form? According to the evidence, the supply curve for

agricultural products is more steeply sloped than the supply curve for products in

general in many countries. Recent experience provides support for the weak form

of the global scarcity hypothesis. Food insecurity due to price increases is

apparently a real problem.

According to the “2009 Millennium Development Goals Report” issued by the

United Nations:

The declining trend in the rate of undernourishment in developing countries since

1990–1992 was reversed in 2008, largely due to escalating food prices. The propor-

tion of people who are undernourished dropped from about 20 per cent in the early

267Testing the Hypotheses

1990s to about 16 per cent in the middle of the following decade. But provisional

estimates indicate that it rose by a percentage point in 2008. Rapidly rising food

prices caused the proportion of people going hungry in sub-Saharan Africa and

Oceania to increase in 2008. When China is excluded, the prevalence of hunger

also rose in Eastern Asia. In most of the other regions, the effect was to arrest the

downward trend. [p. 11]

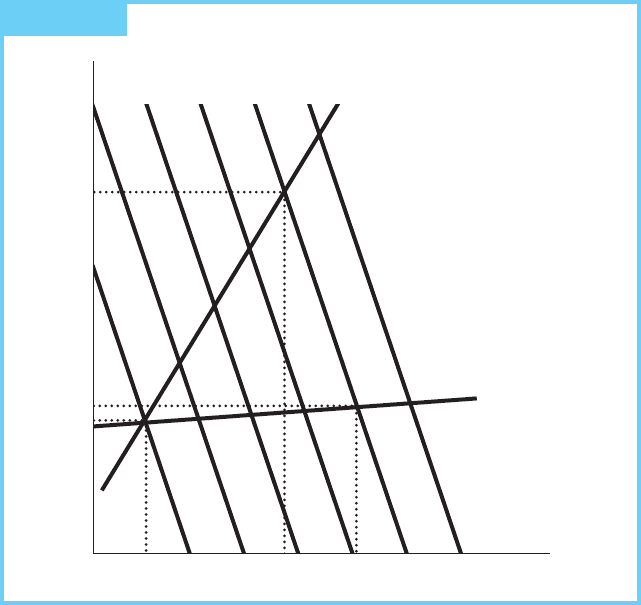

Figure 11.2 shows recent trends in food prices. The last five years have seen

considerable increases in the food price index.

These higher prices are one facet of the threat to food security. Food security is

not the only issue related to food, however. For countries such as the United States,

the looming problem is one of excess, not scarcity, as obesity becomes a serious

health problem. In the United States, per capita food consumption rose 16 percent

between 1970 and 2003. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the

total amount of food available to eat for each person in the United States in 1970

was 1,675 pounds. By 2003, this number had risen to 1,950 pounds. The resulting

increase in per capita calorie consumption rose from 2,234 calories per person

per day in 1970 to 2,757 calories per person per day in 2003!

1

Outlook for the Future

What factors will influence the future relative costs of food? Based upon the

historical experience: (1) the developing nations will need to supply an increasing

share of world food production to meet their increasing shares of population and (2)

1

http://www.ers.usda.gov/AmberWaves/November05/Findings/USFoodConsumption.htm

FIGURE 11.2 Trends in Food Prices

Source:

http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/

250

2002–2004 = 100

210

170

130

90

50

90

* The real price index is the nominal price index deflated by the World Bank Manufactures Unit Value Index (MUV)

91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00

Nominal

Real*

01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 11

268 Chapter 11 Reproducible Private Property Resources: Agriculture and Food Security

the developed nations must continue their role as a major food exporter. The ability

of developing nations to expand their role is considered in the next section as a part

of the food-distribution problem. In this section, therefore, we deal with forces

affecting productivity in the industrialized nations.

Agriculture in the Industrialized World. Rather dramatic historic increases in

crop productivity were stimulated by improvements in machinery; increasing

utilization of commercial fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides; developments in

plant and animal breeding; expanding use of irrigation water; and adjustments in

location of crop production. For example, in the United States, corn is produced on

more acreage than any other crop. Yields per acre more than quadrupled between

1930 and 2000 from approximately 30 bushels per acre to about 130 bushels per

acre. Milk and dairy production have also shown marked productivity improvements.

In 1944, average production per cow was 4,572 pounds of milk. By 1971, the average

had risen to 10,000 pounds. By the end of the twentieth century, the average had

risen to 17,000 pounds per cow! Other areas of the livestock industry show similar

trends.

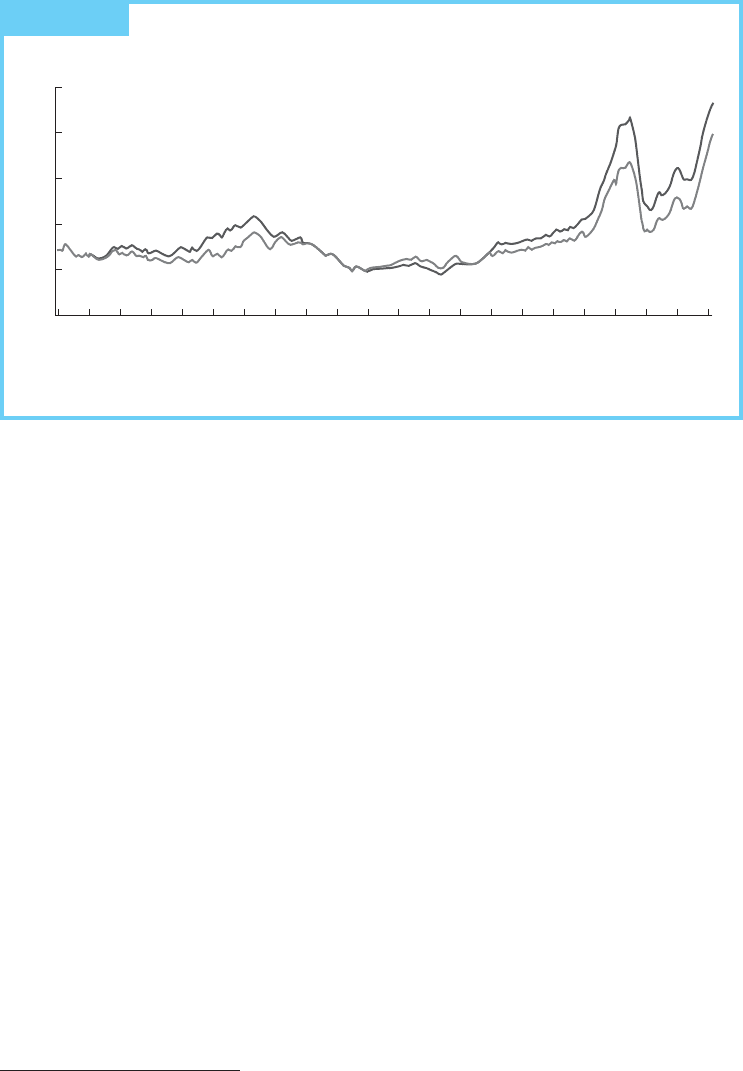

Table 11.1 shows some of the trends in U.S. agriculture during the twentieth

century. Among other aspects, it points out that a huge shift to mechanization has

occurred as farm equipment (dependent upon depletable fossil fuels) is substituted

for animal power. This trend has not only provided the foundation for an increase

in scale of the average farm and a reduction in the number of farms, but it also

raises questions about the sustainability of that path.

Technological Progress. Technological progress provides the main source of

optimism about continued productivity increases. Three techniques have

received significant attention recently: (1) recombinant DNA, which permits

recombining genes from one species with those of another; (2) tissue culture,

which allows whole plants to be grown from single cells; and (3) cell fusion,

which involves uniting the cells of species that would not normally mate to create

new types of plants different from “parent” cells. Applications for these genetic

engineering techniques include:

1. Making food crops more resistant to diseases and insect pests;

2. Creating hardy, new crop plants capable of surviving in marginal soils;

3. Giving staple food crops such as corn, wheat, and rice the ability to make their

own nitrogen-rich fertilizers by using solar energy to make ammonia from

nitrogen in the air;

4. Increasing crop yields by improving the way plants use the sun’s energy

during photosynthesis.

Five concerns have arisen regarding the ability of the industrial nations to achieve

further productivity gains: the declining share of land allocated to agricultural use;

the rising cost of energy; the rising environmental cost of traditional forms of

agriculture; the role of price distortions in agricultural policy; and potential side

effects from the new genetically modified crops. A close examination of these

269Testing the Hypotheses

TABLE 11.1 Trends in U.S. Agriculture: A Twentieth-Century Time Capsule

.

Beginning of the Century

(1900)

zEnd of the Century

(1997)

Number of Farms

5,739,657 1,911,859

Average Farm Acreage 147 acres 487 acres

Crops

Percent of Farms Growing:

Corn 82% 23%

Hay 62% 46%

Vegetables 61% 3%

Irish Potatoes 49% 1%

Orchards

1

48% 6%

Oats 37% 5%

Soybeans - 0 - 19%

Livestock

Percent of Farms Raising:

Cattle 85% 55%

Milk Cows 79% 6%

Hogs and Pigs 76% 6%

Chickens

2

97% 5%

Farm Mechanization

Percent of Farms with:

Wheel Tractors

3

4% 89%

Horses 79% 20%

Mules 26% 2%

Government Payments - 0 - $5 billion

Percent Population Living

on Farms

4

39.2% 1.8% (1990)

Percent Labor Force on

Farms

5

38.8% 1.7% (1990)

Source:

USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service on Web at

http://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/Trends_in_U.S._Agriculture/time_capsule.asp/.

1

1929 Census of Agriculture.

2

1910 Census of Agriculture.

3

1920 Census of Agriculture.

4

Bureau of the Census.

5

Bureau of Labor Statistics.

270 Chapter 11 Reproducible Private Property Resources: Agriculture and Food Security

concerns reveals that current agricultural practices in the industrial nations may

be neither efficient nor sustainable and a transition to agriculture that is both

efficient and sustainable could involve lower productivity levels.

Allocation of Agricultural Land. According to the 2002 Census of U.S. Agriculture,

land in farms was estimated at 938 million acres, down from approximately 955 million

acres in 1997. The corresponding acreage in 1974 was 1.1 billion acres. Total cropland

in 2002 was approximately 434 million acres, 55 million of which was irrigated.

The corresponding irrigated acreage in 1974 was approximately 41 million acres.

While total land in farms has dropped considerably, irrigated acreage has been rising.

More than 50 percent of the agricultural cropland has been converted to

nonagricultural purposes since 1920. A simple extrapolation of this trend would

certainly raise questions about our ability to increase productivity at historical

rates. Is a simple extrapolation reasonable? What determines the allocation of land

between agricultural and nonagricultural uses?

Agricultural land will be converted to nonagricultural land when its profitability

in nonagricultural uses is higher (Chapter 10). If we are to explain the historical

experience, we must be able to explain why the relative value of land in agriculture

has declined.

Two factors stand out. First, an increasing urbanization and industrialization of

society rapidly raised the value of nonagricultural land. Second, rising productivity

of the remaining land allowed the smaller amount of land to produce a lot more

food. Less agricultural land was needed to meet the demand for food.

It seems unlikely that simple extrapolation of the decline in agricultural land of the

magnitude since 1920 would be accurate. Since the middle of the 1970s, the

urbanization process has diminished to the point that some urban areas (in the

United States) are experiencing declining population. This shift is not merely

explained by suburbia spilling beyond the boundaries of what was formerly

considered urban. For the first time in our history, a significant amount of population

has moved from urban to rural areas.

Furthermore, as increases in food demand are accompanied by increased prices of

food, the value of agricultural land should increase. Higher food prices would tend to

slow conversion and possibly even reverse the trend. To make this impact even greater,

several states have now allowed agricultural land to either escape the property tax

(until it is sold for some nonagricultural purpose) or to pay lower rates.

Worldwide, irrigated acreage is on the rise, though the rate of increase has been

falling. In 1980, 209,292 hectares were irrigated globally—150,335 of these in

developing countries. By 2003, the number of total irrigated hectares had grown to

277,098, with some 207,965 of these in developing countries (Gleick, 2006).

2

What about agricultural land that is still used for agriculture, but not used for

growing food? A recent trend in conversion of land to grow corn solely to be used

in the production of ethanol has contributed to rising food prices and reduced food

aid to developing countries.

2

One hectare is equivalent to 2.47 acres.