Tietenberg Tom, Lewis Lynne. Environmental & Natural Resource Economics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

231Potential Remedies

membranes. As of 2005 more than 10,000 desalting plants had been installed or

contracted worldwide. Since 2000, desalination capacity has been growing at

approximately 7 percent per year. Over 130 countries utilize some form of

desalting technology (Gleick, 2006).

According to the World Bank, the cost of desalinized water has dropped from

$1 per cubic meter to an average of $0.50 per cubic meter in a period of five years

(World Bank, 2004). Costs are expected to continue to fall, though not as rapidly.

In the United States, Florida, California, Arizona, and Texas have the largest

installed capacity. However, actual production has been mixed. In Tampa Bay, for

example, a large desalination project was contracted in 1999 to provide drinking

water. This project, while meant to be a low cost ($0.45/m

3

) state-of-the-art

project, was hampered by difficulties. Although the plant became fully operational

at the end of 2007, projected costs were $0.67/m

3

(Gleick, 2006). In 1991, Santa

Barbara, California, commissioned a desalination plant in response to the previ-

ously described drought that would supply water at a cost expected to be $1.22/m

3

.

Shortly after construction was completed, however, the drought ended and the

plant was never operated. In 2000 the city sold the plant to a company in Saudi

Arabia. It has been decommissioned, but remains available should current supplies

run out. Despite the fact that 2007 was the driest year in over 100 years, the city

projects that the plant will not be needed in the near future. While desalination

holds some appeal as an option in California, it is only currently economically

feasible for coastal cities, and concerns about the environmental impacts, such as

energy usage and brine disposal, remain to be addressed.

11

In early 2011, a large desalination project in Dubai and another in Israel were

scrapped mid-construction due to lower-than-expected demand growth and cost,

respectively. These two projects represented 10 percent of the desalination market.

12

Summary

In general, any solution should involve more widespread adoption of the principles

of marginal-cost pricing. More-expensive-to-serve users should pay higher prices

for their water than their cheaper-to-serve counterparts. Similarly, when new,

much-higher-cost sources of water are introduced into a water system to serve the

needs of a particular category of user, those users should pay the marginal cost of

that water, rather than the lower average cost of all water supplied. Finally, when a

rise in the peak demand triggers a need for expanding either the water supplies or

the distribution system, the peak demanders should pay the higher costs associated

with the expansion.

These principles suggest a much more complicated rate structure for water than

merely charging everyone the same price. However, the political consequences of

introducing these changes may be rather drastic.

11

California Coastal Commission, http://www.coastal.ca.gov/.

12

Global Water Intelligence, Vol. 12, No. 1, http://www.globalwaterintel.com/archive/12/1/need-to-

know/desal-misery.html

232 Chapter 9 Replenishable but Depletable Resources: Water

One strategy that has received more attention in the last couple of decades is the

privatization of water supplies. The controversies that have arisen around this

strategy are intense (see Debate 9.2).

However, it is important to distinguish between the different types of privatiza-

tion since they can have quite different consequences. Privatization of water supplies

creates the possibility of monopoly power and excessive rates, but privatization of

access rights (such as discussed in Example 9.1 and Debate 9.2) does not.

Whereas privatization of water supplies turns the entire system over to the pri-

vate sector, privatization of access rights only establishes specific quantified rights

to use the publicly supplied water. As discussed earlier in this chapter, privatization

of access rights is one way to solve the excesses that follow from the free-access

problem, since the amount of water allocated by these rights would be designed to

correspond to the amount available for sustainable use. And if these access rights

are allocated fairly (a big if!) and if they are enforced consistently (another big if!),

the security that enforceability provides can protect users, including poor or

indigenous users, from encroachment. The question then becomes, “Are these

rights allocated fairly and enforced consistently?” When they are, privatization of

access rights can become beneficial for all users, not merely the rich.

DEBATE

9.2

Should Water Systems Be Privatized?

Faced with crumbling water supply systems and the financial burden from water

subsidies, many urban areas in both industrialized and developing countries have

privatized their water systems. Generally this is accomplished by selling the publicly

owned water supply and distribution assets to a private company. The impetus

behind this movement is the belief that private companies can operate more effi-

ciently (thereby lowering costs and, hence, prices) and do a better job of improving

both water quality and access by infusing these systems with new investment.

The problem with this approach is that water suppliers in many areas can act

as a monopoly, using their power to raise rates beyond competitive levels, even if

those rates are, in principle, subject to regulation. What happened in

Cochabamba, Bolivia, illustrates just how serious a problem this can be.

After privatization in Cochabamba, water rates increased immediately, in some

cases by 100–200 percent. The poor were especially hard-hit. In January 2000, a

four-day general strike in response to the water privatization brought the city to a

total standstill. In February the Bolivian government declared the protests illegal

and imposed a military takeover on the city. Despite over 100 injuries and one

death, the protests continued until April when the government agreed to terminate

the contract.

Is Cochabamba typical? It certainly isn’t the only example of privatization

failure. Failure (in terms of a prematurely terminated privatization contract) also

occurred in Atlanta, Georgia, for example. The evidence is still out on its overall

impact in other settings and whether we can begin to extract preconditions for its

successful introduction, but it is very clear that privatization of water systems is

no panacea and can be a disaster.

233GIS and Water Resources

GIS and Water Resources

Allocation of water resources is complicated by the fact that water moves! Water

resources do not pay attention to jurisdictional boundaries. Geographic informa-

tion systems (GIS) help researchers use watersheds and water courses as organizing

tools. For example, Hascic and Wu (2006) use GIS to help examine the impacts of

land use changes in the United States on watershed health, while Lewis, Bohlen,

and Wilson (2008) use GIS to analyze the impacts of dams and rivers on property

values in Maine. This enormously powerful tool is making economic analysis easier

and the visualizing of economic and watershed data in map form helps in the

communication of economic analysis to noneconomists. Check out the EPA’s Surf

Your Watershed site at http://cfpub.epa.gov/surf/locate/index.cfm for GIS maps of

your watershed, including stream flow, water use, and pollution discharges, or

USGS.gov for surface- and groundwater resources maps.

Summary

On a global scale, the amount of available water exceeds the demand, but at

particular times and in particular locations, water scarcity is already a serious

problem. In a number of locations, the current use of water exceeds replenishable

supplies, implying that aquifers are being irreversibly drained.

Efficiency dictates that replenishable water be allocated so as to equalize the

marginal net benefits of water use even when supplies are higher or lower than

normal. The efficient allocation of groundwater requires that the user cost of that

depletable resource be considered. When marginal-cost pricing (including

marginal user cost) is used, water consumption patterns strike an efficient balance

between present and future uses. Typically, the marginal pumping cost would rise

over time until either it exceeded the marginal benefit received from that water or

the reservoir runs dry.

In earlier times in the United States, markets played the major role in allocating

water. But more recently governments have begun to play a much larger role in

allocating this crucial resource.

Several sources of inefficiency are evident in the current system of water alloca-

tion in the southwestern United States. Transfers of water among various users are

restricted so that the water remains in low-valued uses while high-valued uses are

denied. Instream uses of water are actively discouraged in many western states.

Prices charged for water by public suppliers typically do not cover costs, and the

rate structures are not designed to promote efficient use of the resource. For

groundwater, user cost is rarely included, and for all sources of water, the rate

structure does not usually reflect the cost of service. These deficiencies combine to

produce a situation in which we are not getting the most out of the water we are

using and we are not conserving sufficient amounts for the future.

Reforms are possible. Allowing conservers to capture the value of water saved by

selling it would stimulate conservation. Creating separate fishing rights that can be

234 Chapter 9 Replenishable but Depletable Resources: Water

sold or allowing environmental groups to acquire and retain instream water rights

would provide some incentive to protect streams as fish habitats. More utilities

could adopt increasing block pricing as a means of forcing users to realize and to

consider all of the costs of supplying the water.

Water scarcity is not merely a problem to be faced at some time in the distant

future. In many parts of the world, it is already a serious problem and unless

preventive measures are taken, it will get worse. The problem is not insoluble,

though to date the steps necessary to solve it have proved insufficient.

Discussion Questions

1. What pricing system is used to price the water you use at your college or uni-

versity? Does this pricing system affect your behavior about water use (length

of showers, etc.)? How? Could you recommend a better pricing system in this

circumstance? What would it be?

2. In your hometown what system is used to price the publicly supplied water?

Why was that pricing system chosen? Would you recommend an alternative?

3. Suppose you come from a part of the world that is blessed with abundant

water. Demand never comes close to the available amount. Should you be

careful about the amount you use or should you simply use whatever you

want whenever you want it? Why?

Problems

1. Suppose that in a particular area the consumption of water varies tremen-

dously throughout the year, with average household summer use exceeding

winter use by a great deal. What effect would this have on an efficient rate

structure for water?

2. Is a flat-rate or flat-fee system more efficient for pricing scarce water? Why?

3. One major concern about the future is that water scarcity will grow, particu-

larly in arid regions where precipitation levels may be reduced by climate

change. Will our institutions provide for an efficient response to this problem?

To think about this issue, let’s consider groundwater extraction over time

using the two-period model as our lens.

a. Suppose the groundwater comes from a well you have drilled upon your land

that taps an aquifer that is not shared with anyone else. Would you have an

incentive to extract the water efficiently over time? Why or why not?

b. Suppose the groundwater is obtained from your private well that is drilled

into an aquifer that is shared with many other users who have also drilled

private wells. Would you expect that the water from this common aquifer

be extracted at an efficient rate? Why or why not?

235Further Reading

4. Water is an essential resource. For that reason moral considerations exert

considerable pressure to assure that everyone has access to at least enough

water to survive. Yet it appears that equity and efficiency considerations may

conflict. Providing water at zero cost is unlikely to support efficient use

(marginal cost is too low), while charging everyone the market price

(especially as scarcity sets in) may result in some poor households not being

able to afford the water they need. Discuss how block rate pricing attempts to

provide some resolution to this dilemma. How would it work?

Further Reading

Anderson, Terry L. Water Crisis: Ending the Policy Drought (Washington, DC: Cato Institute,

1983): 81–85. A provocative survey of the political economy of water, concluding that we

have to rely more on the market to solve the crisis.

Colby, Bonnie G., and Tamra Pearson D’Estree. “Economic Evaluation of Mechanisms to

Resolve Water Conflicts,” Water Resources Development Vol. 16 (2000): 239–251.

Examines the costs and benefits of various water dispute resolution mechanisms.

Dinar, Ariel, and David Zilberman, eds. The Economics and Management of Water and

Drainage in Agriculture (Norwell, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1991). Examines the

special issues associated with water use in agriculture.

Easter, K. William, M. W. Rosegrant, and Ariel Dinar, eds. Markets for Water: Potential and

Performance (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1998). Not only develops the

necessary conditions for water markets and illustrates how they can improve both water

management and economic efficiency, but also provides an up-to-date picture of what we

have learned about water markets in a wide range of countries, from the United States to

Chile to India.

Harrington, Paul. Pricing of Water Services (Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation

and Development, 1987). An excellent survey of the water pricing practices in the OECD

countries.

MacDonnell, Lawrence J., and David J. Guy. “Approaches to Groundwater Protection in

the Western United States,” Water Resources Research Vol. 27 (1991): 259–265. Discusses

groundwater protection in practice.

Martin, William E., Helen M. Ingram, Nancy K. Laney, and Adrian H. Griffin. Saving

Water in a Desert City (Washington, DC: Resources for the Future, 1984). A detailed look

at the political and economic ramifications of an attempt by Tucson, Arizona, to improve

the pricing of its diminishing supply of water.

Saliba, Bonnie Colby, and David B. Bush. Water Markets in Theory and Practice: Market

Transfers and Public Policy (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1987): 74–77. A highly recom-

mended, accessible study of the way western water markets work in practice in the

United States.

Shaw, W. D. Water Resource Economics and Policy: An Introduction (Cheltenham, UK: Edward

Elgar, 2005) and Griffen, R. C. Water Resource Economics: The Analysis of Scarcity, Policies,

and Projects (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006). Two excellent texts that focus exclu-

sively on water resource economics.

236 Chapter 9 Replenishable but Depletable Resources: Water

Spulber, Nicholas, and Asghar Sabbaghi. Economics of Water Resources: From Regulation to

Privatization (Hingham, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1993). Detailed analysis of

the incentive structures created by alternative water management regimes.

Von Weizsäcker, Ernst Ulrich, Oran R. Young, et al., eds. Limits to Privatization: How to

Avoid too Much of a Good Thing (London, UK: Earthscan, 2005). Case studies on attempts

at privatization (including, but not limited to, privatization of water supplies) that assess

the factors associated with success or failure.

Young, R. A. Determining the Economic Value of Water: Concepts and Methods (Washington,

DC: Resources for the Future, Inc., 2005). A detailed survey and synthesis of theory and

existing studies on the economic value of water in various uses.

Additional References and Historically Significant References are available on this book’s

Companion Website: http://www.pearsonhighered.com/tietenberg/.

10

10

237

A Locationally Fixed, Multipurpose

Resource: Land

Buy land, they’re not making it anymore.

—Mark Twain, American Humorist

A land ethic . . . reflects the existence of an ecological conscience, and this

in turn reflects a conviction of individual responsibility for the health of

the land. Health is the capacity of the land for self-renewal.

Conservation is our effort to understand and preserve this capacity.

—Aldo Leopold, Sand County Almanac

Introduction

Land occupies a special niche not only in the marketplace, but also deep in the

human soul. In its role as a resource, land has special characteristics that affect its

allocation. Topography matters, of course, but so does its location, especially since

in contrast to many other resources, land’s location is fixed. It matters not only

absolutely in the sense that the land’s location directly affects its value, but also

relatively in the sense that the value of any particular piece of land is also affected by

the uses of the land around it. In addition, land supplies many services, including

providing habitat for all terrestrial creatures, not merely humans.

Some contiguous uses of land are compatible with each other, but others are not.

In the case of incompatibility, conflicts must be resolved. Whenever the prevailing

legal system treats land as private property, as in the United States, the market is

one arena within which those conflicts are resolved.

How well does the market do? Are the land-use outcomes and transactions

efficient and sustainable? Do they reflect the deeper values people hold for land?

Why or why not?

In this chapter, we shall begin to investigate these questions. How does the

market allocate land? How well do market allocations fulfill our social criteria?

Where divergences between market and socially desirable outcomes occur, what

policy instruments are available to address the problems? How effective are they?

Can they restore conformance between goals and outcomes?

Net Benefits

per Acre

A

Residential Development

Wilderness

Agriculture

Distance to Center

BC

0

238 Chapter 10 A Locationally Fixed, Multipurpose Resource: Land

FIGURE 10.1 The Allocation of Land

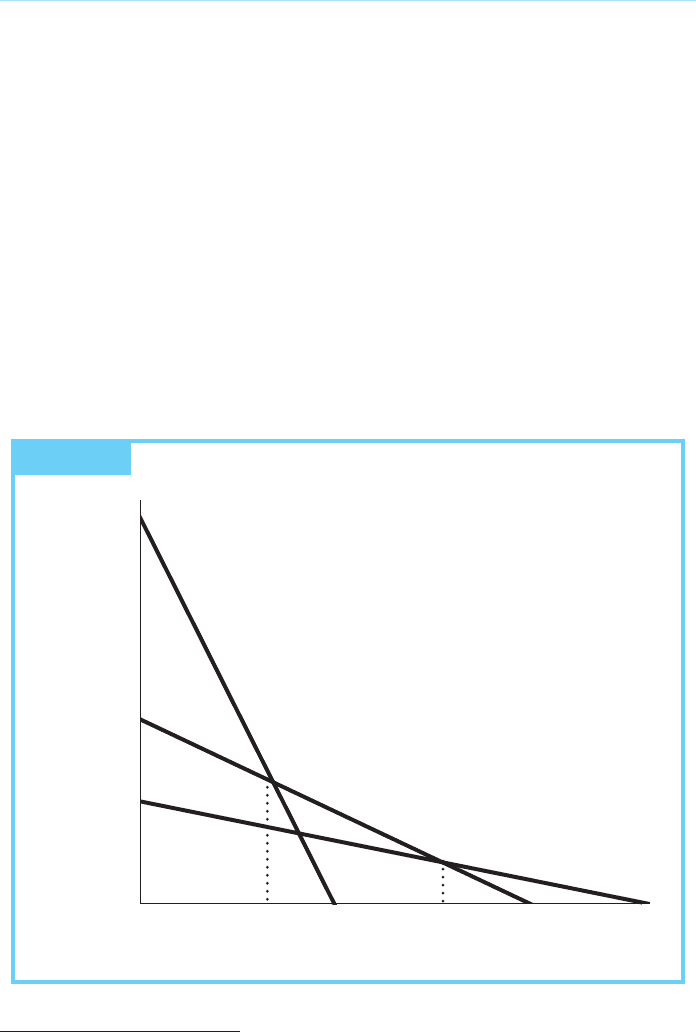

The Economics of Land Allocation

Land Use

In general, as with other resources, markets tend to allocate land to its highest-

valued use. Consider Figure 10.1, which graphs three hypothetical land uses—

residential development, agriculture, and wilderness.

1

The left-hand side of the

horizontal axis represents the location of the marketplace where agricultural

produce is sold. Moving to the right on that axis reflects an increasing distance

away from the market.

The vertical axis represents net benefits per acre. Each of the three functions,

known in the literature as bid rent functions, records the relationship between

distance to the center of the town or urban area and the net benefits per acre

received from each type of land use. A bid rent function expresses the maximum net

benefit per acre that could be achieved by that land use as a function of the distance

from the center. All three functions are downward sloping because the cost of

transporting both goods and people lowers net benefits per acre more for distant

locations.

1

For our purposes, wilderness is a large, uncultivated tract of land that has been left in its natural state.

239The Economics of Land Allocation

According to Figure 10.1, a market process that allocates land to its highest-

valued use would allocate the land closest to the center to residential

development (a distance of A), agriculture would claim the land with the next

best access (A to B), and the land farthest away from the market would remain

wilderness (from B to C). This allocation maximizes the net benefits society

receives from the land.

Although very simple, this model also helps to clarify both the processes by

which land uses change over time and the extent to which market processes are

efficient, subjects we explore in the next two sections.

Land-Use Conversion

Conversion from one land use to another can occur whenever the underlying bid

rent functions shift. According to the Economic Research Service of the U.S.

Department of Agriculture, “Urban land area quadrupled from 1945 to 2002,

increasing at about twice the rate of population growth over this period.”

Conversion of nonurban land to residential development could occur when the

bid rent function for urban development shifts up, the bid rent function for

nonurban land uses shifts down, or any combination of the two. Two sources of

the conversion of land to urban uses in the United States stand out: (1) increasing

urbanization and industrialization rapidly shifted upward the bid rent functions

for urban land, including residential, commercial, industrial, and even associated

transportation (airports, highways, etc.) and recreational (parks, etc.) uses;

(2) rising productivity of the agricultural land allowed the smaller amount of land

to produce a lot more food. Less agricultural land was needed to meet the rising

food demand than would otherwise have been the case.

Many developing countries are witnessing the conversion of wilderness areas

into agriculture.

2

Our simple model also suggests some reasons why that may be

occurring.

Relative increases (shifts up) in the bid rent function for agriculture could result

from the following:

●

Domestic population growth that increases the domestic demand for food

●

Opening of export markets for agriculture that increase the foreign demand

for local crops

●

Shifting from subsistence crops to cash crops (such as coffee or cocoa) for

exports, thereby increasing the profit per acre

●

New planting or harvesting technologies that lower the cost and increase the

profitability of farming

●

Lower agricultural transport costs due, for example, to the building of new

roads into forested land

2

Wilderness is also being lost in many of the more remote parts of industrialized countries in part due to

the proliferation of second homes in particularly scenic areas.

240 Chapter 10 A Locationally Fixed, Multipurpose Resource: Land

Some offsetting increases in the bid rent function for wilderness could result from

an increasing demand for wilderness-based recreation or increases in preferences

for wilderness due to increases in public knowledge about the ecosystem goods and

services wilderness provides.

Although only three land uses are drawn in Figure 10.1 for simplicity, in actual

land markets, of course, all other uses, including commercial and industrial, must

be added to the mix. Changes in the bid rent functions for any of these uses could

trigger conversions.

Sources of Inefficient Use and Conversion

In the absence of any government regulation, are market allocations of land

efficient? In some circumstances they are, but certainly not in all, or even most,

circumstances.

We shall consider several sets of problems associated with land-use inefficiencies

that commonly arise in the industrialized countries: sprawl and leapfrogging, the

effects of taxes on land-use conversion, incompatible land uses, undervaluation of

environmental amenities, and market power. While some of these may also plague

developing countries, we follow with a section that looks specifically at some

special problems developing countries face.

Sprawl and Leapfrogging

Two problems associated with land use that are receiving a lot of current attention

are sprawl and leapfrogging. From an economic point of view, sprawl occurs when

land uses in a particular area are inefficiently dispersed, rather than efficiently

concentrated. The related problem of leapfrogging refers to a situation in which

new development continues not on the very edge of the current development, but

farther out. Thus, developers “leapfrog” over contiguous, perhaps even vacant,

land in favor of land that is farther from the center of economic activity.

Several environmental problems are intensified with dispersed development.

Trips to town to work, shop, or play become longer. Longer trips not only mean

more energy consumed, but also frequently they imply a change from the least

polluting modes of travel (such as biking or walking) to automobiles, a much more

heavily polluting source. Assuming the cars used for commuting are fueled by

gasoline internal combustion engines, dispersal drives up the demand for oil

(including imported oil), results in higher air-pollutant emissions levels (including

greenhouse gases), and increases the need for more steel, glass, and other raw

materials to supply the increase in the number of vehicles demanded.

The Public Infrastructure Problem. To understand why inefficient levels of

sprawl and leapfrogging might be occurring, we must examine the incentives faced

by developers and how those incentives affect location choices.

One set of inefficient incentives can be found in the pricing of public services.

New development beyond the reach of current public sewer and water systems may