The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

POLICY CHANGES 437

natural disasters as flood or drought and how to increase the amount

of land under cultivation. But the Taiho and Yoro codes contain only

one article that touches on these problems.*

6

In regard to the rec-

lamation of wasteland, a distinction was made between private land

(shiden)

and state land

(koden).

The former was personal-share land

possessed and used by farmers, whereas the latter, classified as sur-

plus land

(joden),

was unallocated land that was a source of income for

the state. When a piece of private land was abandoned, another

farmer was allowed to recultivate it and to enjoy its yield for three

years,

after which it was returned to the state. A farmer who brought

state wasteland back into cultivation could keep what was produced

for six years, and then he was required to turn over the land to

provincial authorities.

The problem of developing virgin land was more complicated. The

code merely stipulated that a provincial governor might open and

benefit from fields opened up during his incumbency. At the end of his

term of office, such land was to be returned to the state. Surprisingly,

the statute does not stipulate the conditions under which court nobles

or farmers might develop virgin land. Silence on this point should not

be mistaken, however, for prohibition. It

was

only natural that farmers

should have been interested in expanding their fields, and the govern-

ment in increasing its income. We assume, therefore, that peasants

were customarily permitted to convert nearby land into paddy fields,

probably gaining possession of such land for life, as in the case of

personal-share land. In general, land development was undertaken by

the state and was represented in local areas by provincial and district

officials. The involvement of court aristocrats in land development was

prohibited, but local peasants faced no such law, receiving usufructu-

ary rights to the paddy fields that they developed."

Because it was difficult to gain private possession of cultivated land,

powerful aristocrats and local gentry were, not surprisingly, drawn to

illegal methods of obtaining and developing virgin land. An edict

issued in the twelfth month of 711 strictly prohibited activity that

would decrease the income that farmers obtained from uncultivated

common land.*

8

But the edict nevertheless allowed a court aristocrat,

or member of the local gentry, to request through a provincial gover-

nor permission to cultivate a piece of virgin land at his own personal

expense. The very existence of the stipulation indicates that the state,

36 Ryo

no

shuge,

KT 23.370-2. 37 Ibid., p. 372.

38 ShokuNihongi, Wado 4 (711), 12/6 KT 2.47.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

438 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

finding it impossible to prohibit all invasions of common land, was

yielding to the aristocrats' land hunger and, at the same time, trying to

increase the amount of arable land. Twelve years later, in 723, a new

law ruled that some newly developed land could be privately possessed

by the developer and passed on to his descendants for three genera-

tions,

but only during the lifetime of the developer if an irrigation

system was already in existence.

39

One year before this law was issued, a plan had been devised for

opening up

a

million

cho

of land for rice production. Because ninth- and

tenth-century documents suggest that the total amount of land under

cultivation was then about a million cho, the implementation of this

ambitious plan would have doubled Japan's arable land. But it was

merely

a

paper

plan.

The

723 law

may have been issued because the plan

of the previous year could not be implemented, although we have no

definite proof of

a

link between the

two.

A

shortage of rice land undoubt-

edly lay behind the 723 law, which served to benefit farmers who had

opened up virgin land near their allotments. But the law may also have

been prompted by the demands of aristocrats who had the capital and

labor needed for building irrigation systems. Finally, there

was a

persis-

tent demand for land, which the government may have been unable to

satisfy. Prince Nagaya,

as

head of the anti-Fujiwara faction, had risen to

the highest seat of authority after the death of Fujiwara no Fuhito in

720.

In order to maintain his position in the face of opposition from

Fuhito's descendants, he must have been impelled to buy ruling-class

support by favoring legislation that would permit the private possession

of land. We should note, however, that the law of 723 was only a

compromise with the principles of state control: Eventually all fields

had to be returned to the state. The old one-generation restriction still

applied to personal-share land, and the new three-generation rule was

modeled on earlier rights extended to holders of "upper-merit land"

(jokoden).

Thus the

ritsuryo

land system was by no means dead.

Nara records tell us little about land development after 723. It is

unlikely, however, that many new fields were brought under cultiva-

tion as a result of the new provision. Restrictions incorporated into the

law probably reduced its effectiveness. But twenty years later another

edict drastically reduced these restrictions and enabled private indi-

viduals to hold rice land in perpetuity.*> The 743 edict, like the one

39 Shoku Nihongi, Yoro 7 (723), 4/17 KT 2.96.

40 Several texts of this law are extant, but the best one is in the

Shoku

Nihongi, Tempyo 15 (743),

5/27 KT 2.174. The text also can be found in the Ruiju sandai kyaku, KT 25.441, and in the

Ryo no

shuge,

KT 23.372.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

POLICY CHANGES 439

issued in 723, arose out of a new situation in court politics. Now

Tachibana no Moroe (684-757) was the dominant political figure, and

he,

like Prince Nagaya before him, was forced to make it easier for

aristocrats and religious institutions to become private owners of rice

land. Until 743, only one person had ever had private possession of

land in perpetuity: Fujiwara no Kamatari (614-69), founder of the

Fujiwara clan and a prominent post-645 reformer who had received a

grant of "great-merit land"

(daikoden).

But the edict of 743 made it

possible for aristocrats generally to acquire private ownership of land

and to pass it on to their descendants, thereby altering the course of

economic history in fundamental ways.

State recognition of the private and permanent tenure of rice land

meant that two opposing principles prevailed: the old principle that

the state allocated and reallocated rice land already under cultivation

and the new principle of private ownership by persons who had devel-

oped land. That is, in a given village some land was designated as

personal-share land, or surplus land, in accordance with the

ritsuryo

principle of state control, and all other land was newly cultivated land

that was privately owned. It became increasingly difficult to disentan-

gle the two, making it hard for governmental authorities to preserve

the land allotment system.

The 743 edict also altered the meaning of the terms "private land"

(shideri)

and "state land"

(koden).

According to earlier

law,

private land

was that with a specific usufructuary, most of which was personal-

share allotments but included plots of land distributed to persons

holding public offices and ranks. State land, on the other hand, was

rice land without a specific usufructuary and consisting mainly of

surplus fields

(jdderi).

But the 743 law gave "private land" a new

meaning: fields privately owned in perpetuity and recognized by the

state.

State land, on the other hand, was now personal-share fields

temporarily allotted to individuals in accordance with the old

ritsuryo

system. Whereas previous laws distinguished between private and

state land in terms of the presence or absence of usufructuary rights,

the 743 law did so in terms of private possession and state control.

Another change ushered in by the 743 law arose from persons being

permitted to cultivate an amount of land determined by political sta-

tus:

An official of the first rank could develop five hundred cho of

land, but a person without rank could develop only ten. It is possible

to think of this change as adding another restriction to those incorpo-

rated in the 723 law. Some scholars believe this explains why the 743

law was issued. Earlier codes had not dealt with the question of land

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

440 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

development, but if they had, limits on the amount of land that a

single individual could bring under cultivation would probably have

been deemed necessary. Therefore Yoshida Takashi concluded that

although the 743 law destroyed basic features of the

ritsuryo

land law, it

emerged from problems with the law's administration.

41

By making it

clear that the 743 regulation was an attempt to resolve such problems,

Yoshida made an important contribution. But the

743

restrictions were

loose and were probably not enforced. Restrictions on the amount of

land that temples could develop were not even spelled out, and after

743,

large amounts of

new

rice land appeared.

42

Some two decades later, in 765 when the court was dominated by

the Buddhist priest Dokyo (d. 772) and pro-Buddhist policies were

being adopted, land development by non-Buddhist institutions or aris-

tocratic individuals was prohibited.

4

^ Development by Buddhist tem-

ples was, on the other hand, implicitly approved. But when Dokyo fell

from power in 770, the provisions of the 743 law were apparently

restored.

44

Records show that during the remaining century and a

quarter of

ritsuryo

history, the amount of land brought under cultiva-

tion increased continuously and markedly.

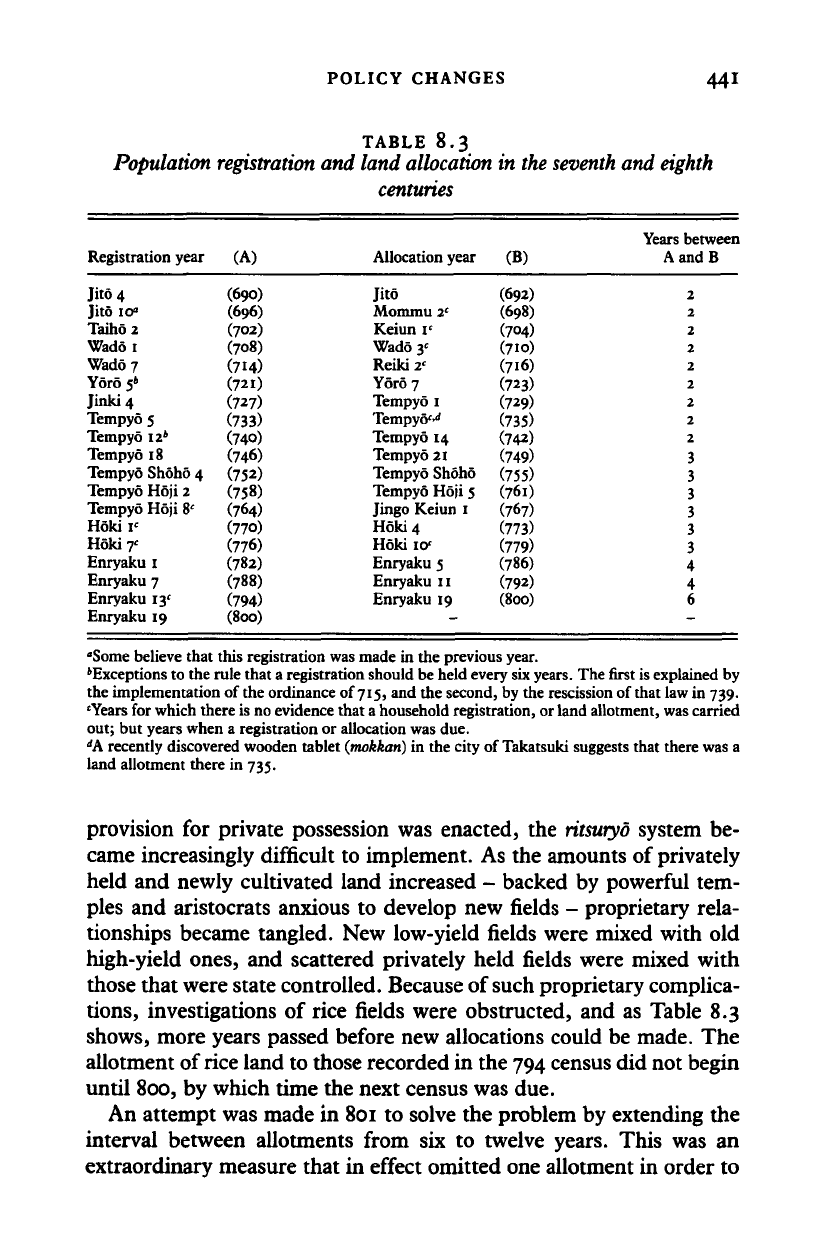

In looking back over changes in land policy, we see two distinct

periods of land system disintegration. First is the period after 743

when individuals or religious institutions were permitted to possess

newly developed rice land personally and in perpetuity. This period

ended in 801 when the interval between allotments was lengthened

from six to twelve years.

4

? The second period lasted from about 800 to

the early tenth century when the

ritsuryo

land system virtually disap-

peared. A study of household registers and land allotment records

down to 800 provides results shown in Table 8.3. Two points should

be made about these figures. First, with only two exceptions, a census

was taken every six years. Second, the length of time between a census

and the following allotment was at first two years but by 800 was

lengthened to six.

Before 743, when reallotments were carried out regularly, they were

made two years after each census. But after the 743 edict, when the

41 Yoshida Takashi, Ritsuryo kokka

to

kodai

no

shakai, pp. 289-347.

42 Farris considers the great smallpox epidemic of 735-7 to have been the major factor in the

government's decision to eliminate restrictions on tenure; see Population, Disease and Land,

pp.

64-81.

43 Shoku Nihongi, Tempyo Jingo I (765) 3/5, 2.319.

44 Ruiju sandai kyaku, Council of State order, Hoki 3 (772) 10/14, KT, 25.441.

45 Ruiju sandai kyaku, Council of State, Enryaku 20 (801) 6/5, which is cited in an order issued

by the Council of State order, Jowa

1

(834) 2/3, KT 25.427.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

POLICY CHANGES 441

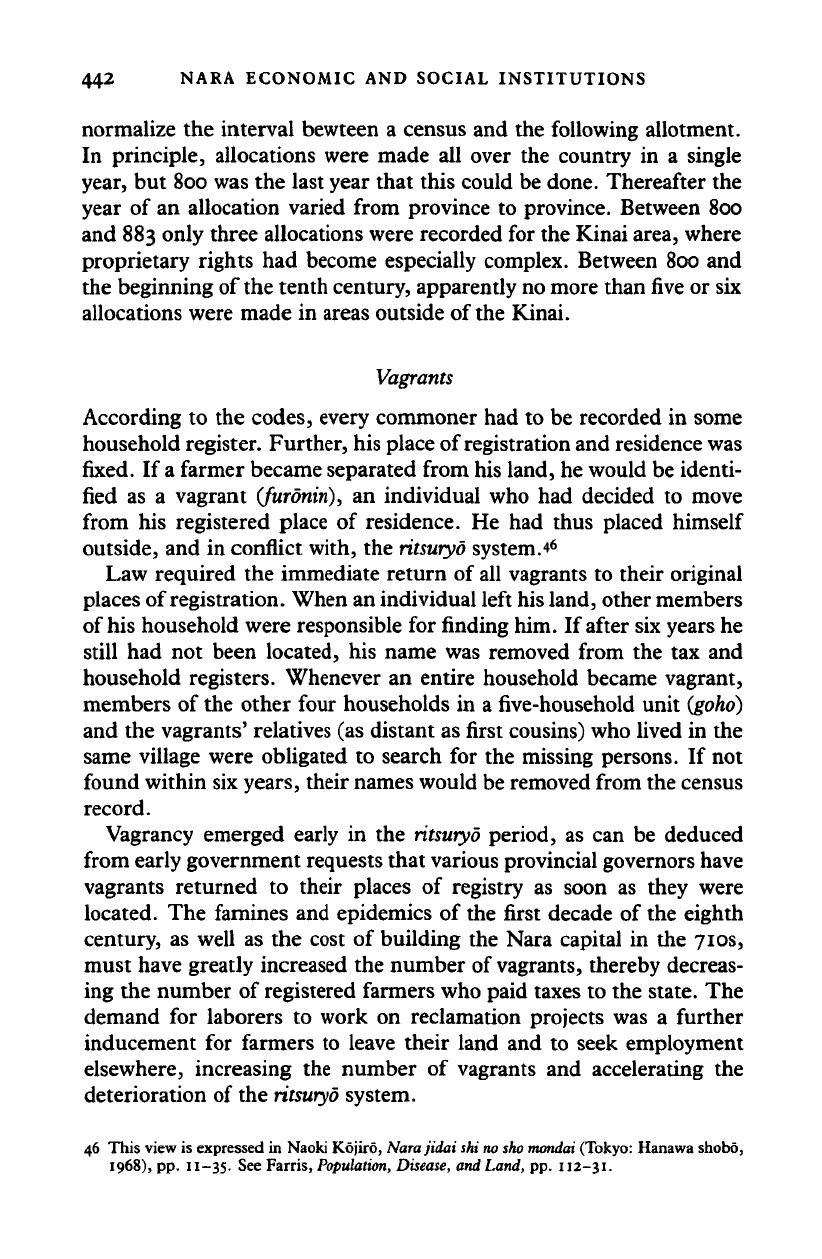

TABLE 8.3

Population

registration

and land

allocation

in the

seventh

and eighth

centuries

Registration year

Jito 4

Jito io°

Taih6 2

Wado 1

Wado 7

Yoro 5'

Jinki 4

Tempyo 5

Tempyo 12*

Tempyo 18

Tempyo Shoho 4

Tempyo Hoji 2

Tempyo Hoji 8'

Hokir

Hokir

Enryaku 1

Enryaku 7

Enryaku 13'

Enryaku 19

(A)

(690)

(696)

(702)

(708)

(714)

(72O

(727)

(733)

(74°)

(746)

(752)

(758)

(764)

(770)

(776)

(782)

(788)

(794)

(800)

Allocation year

Jito

Mommu 2'

Keiun l

e

Wado y

Reiki2'

Yoro 7

Tempyo 1

Tempy^

Tempyo 14

Tempyo 21

Tempyo Shoho

Tempyo Hoji 5

Jingo Keiun 1

H6ki

4

Hold io*

Enryaku 5

Enryaku 11

Enryaku 19

—

(B)

(692)

(698)

(704)

(710)

(716)

(723)

(729)

(735)

(742)

(749)

(755)

(761)

(767)

(773)

(779)

(786)

(792)

(800)

Years between

AandB

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

2

3

3

3

3

3

3

4

4

6

-

"Some believe that this registration was made in the previous year.

'Exceptions to the rule that

a

registration should be held every six

years.

The

first

is explained by

the implementation of the ordinance of

715,

and the second, by the rescission of that law in 739.

'Years for which there

is

no evidence that a household registration, or land allotment, was carried

out; but years when a registration or allocation was due.

d

A recently discovered wooden tablet

(mokkan)

in the city of Takatsuki suggests that there was a

land allotment there in 735.

provision for private possession was enacted, the

ritsuryd

system be-

came increasingly difficult to implement. As the amounts of privately

held and newly cultivated land increased - backed by powerful tem-

ples and aristocrats anxious to develop new fields - proprietary rela-

tionships became tangled. New low-yield fields were mixed with old

high-yield ones, and scattered privately held fields were mixed with

those that were state controlled. Because of such proprietary complica-

tions,

investigations of rice fields were obstructed, and as Table 8.3

shows, more years passed before new allocations could be made. The

allotment of rice land to those recorded in the 794 census did not begin

until 800, by which time the next census was due.

An attempt was made in

801

to solve the problem by extending the

interval between allotments from six to twelve years. This was an

extraordinary measure that in effect omitted one allotment in order to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

442 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

normalize the interval bewteen a census and the following allotment.

In principle, allocations were made all over the country in a single

year, but 800 was the last year that this could be done. Thereafter the

year of an allocation varied from province to province. Between 800

and 883 only three allocations were recorded for the Kinai area, where

proprietary rights had become especially complex. Between 800 and

the beginning of the tenth century, apparently no more than five or six

allocations were made in areas outside of the Kinai.

Vagrants

According to the codes, every commoner had to be recorded in some

household register. Further, his place of registration and residence was

fixed. If

a

farmer became separated from his land, he would be identi-

fied as a vagrant

(furonin),

an individual who had decided to move

from his registered place of residence. He had thus placed himself

outside, and in conflict with, the

ritsuryd

system.-"

Law required the immediate return of all vagrants to their original

places of registration. When an individual left his land, other members

of

his

household were responsible for finding him. If after six years he

still had not been located, his name was removed from the tax and

household registers. Whenever an entire household became vagrant,

members of the other four households in a

five-household

unit

(goho)

and the vagrants' relatives (as distant as first cousins) who lived in the

same village were obligated to search for the missing persons. If not

found within six years, their names would be removed from the census

record.

Vagrancy emerged early in the

ritsuryd

period, as can be deduced

from early government requests that various provincial governors have

vagrants returned to their places of registry as soon as they were

located. The famines and epidemics of the first decade of the eighth

century, as well as the cost of building the Nara capital in the 710s,

must have greatly increased the number of

vagrants,

thereby decreas-

ing the number of registered farmers who paid taxes to the state. The

demand for laborers to work on reclamation projects was a further

inducement for farmers to leave their land and to seek employment

elsewhere, increasing the number of vagrants and accelerating the

deterioration of the

ritsuryd

system.

46 This view is expressed in Naoki Kojiro, Narajidai shi

no

sho

mondai

(Tokyo: Hanawa shobo,

1968),

pp. 11-35. See Farris,

Population,

Disease, and Land, pp. 112-31.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

POLICY CHANGES 443

As early as 715 the state moved to resolve the problem by issuing

what is known as the

"dodan

law."

47

Because the meaning of the word

dodan

is not clear, scholars have reached no consensus on its nature

and results. According to the most recent interpretation, any person

who abandoned his land for a period of more than three months was

responsible for taxes at both his former and present places of resi-

dence.

48

By collecting taxes at both places, officials were attempting to

encourage vagrants to return home, an interpretation that seems to

have more merit than previous ones have.

A new policy toward vagrancy lay behind the 721 law that stated

that when a runaway was found, provincial and district officials were

to escort him home in relays if the original residence was known and if

the vagrant was willing to return.

49

If the original place of residence

was not known, the vagrant's name was entered in the household

register of the area to which he had fled. The intent of earlier laws was

thus undermined, as a vagrant was not permitted to register at his new

location. Yet the revision did not completely eliminate state control

over persons. Like the 723 statute for the development of rice land, it

was intended only to defuse a problem that was becoming increasingly

serious.

Examination of an edict issued in 736 reveals a more fundamental

change in the government's vagrancy policy. 5° The first section re-

quired that a runaway who wished to return to his original place of

registration be given a certificate that contained a statement of his

intention to return. An enforced return in the company of local offi-

cials was not specified. Section 2 stated that a vagrant who desired to

stay at his new address must be allowed to do so if

he

placed his name

on a special roster

(meibo)

that subjected him to corvee and tax levies.

The latter section reveals the desire of the authorities to deal with

vagrants who did not wish to return to their original places of registra-

tion and residence and for whom registration was not clear.

Section 1 did not guarantee government control over vagrancy. Be-

cause enforced returns according to the 721 law were no longer re-

47

Shoku

Nihongi, Reiki I (715) 5/1, KT 1.58-59. A variant text is found in Ruiju sandai kyaku,

Council of State order, Konin 2(811)8/11, KT 25.519-20.

48 Hayakawa Shohachi, Ritsuryo kokka, vol. 4 of Nihon

no rekishi

(Tokyo:

shogakkan, 1974), pp.

286-7; Yoshida Takashi, "Ritsuryo-sei to sonraku," in Iwanami koza: Nihon rekishi, 3.185.

49 Ruiju sandai kyaku edict, Tempyo 8 (736) 2/25, cites the regulation issued on Yoro 5 (721) 4/

27,

KT 25.385.

50 Ruiju sandai kyaku edict, Tempyo 8 (736) 2/25, KT 25.385. A variant interpretation of this

document can be found in Kamada Motokazu, "Ritsuryo kokka no futo taisaku," in Kyoto

daigaku bungakubu, ed., Akamatsu

Toshihide

kyoju taikan kinen kokuski

ronshu

(Kyoto: Fa-

culty of Letters of Kyoto University, 1972), pp. 173-88.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

444 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

quired, it became possible for a certificate-bearing vagrant to use the

excuse that he had changed his mind and would not be returning

home. He might then flee to still another place and once again become

a vagrant. Surely this section of the new edict contributed little to the

resolution of the vagrancy problem.

Section 2, on the other hand, was a more basic change. It made it

possible for a vagrant to stay on where he was and to gain state recogni-

tion of his vagrant status if he paid taxes. The official title of the

"roster" in the 736 law is unclear, but it was probably similar to

"vagrant roster"

(furocho),

a word appearing in ninth-century docu-

ments. Of

course,

a vagrant who was not listed on a household register

received no personal-share land. However, being listed on a "special

roster" made him responsible for paying taxes. In one sense, then, the

new law maintained government control, but in another sense, it di-

minished that control. The 736 law was thus a compromise not unlike

the 743 compromise on land control. The state's hold over people and

land was not completely eliminated, but a significant turn in that

direction was made.'

1

Efforts to place vagrants back under governmental control were not

abandoned after 736, and historical sources reveal cases of vagrants

returning home in accordance with the requirements of

the 721

law. It

is clear, however, that these efforts did not diminish the seriousness of

the 736 compromise, for vagrants and household farmers were hence-

forth treated differently. Toward the end of the eighth century, the

policy of offering status to vagrants and forcing them to pay taxes was

further strengthened. After 797, when the establishment of the "va-

grant roster" was ordered, the policy change became firmly rooted, an

important development in the disintegration of state control over agri-

cultural producers.

Loans

During the Nara period

a

class of rich farmers emerged in agricultural

villages throughout Japan. Their great wealth came in part from loans

made at high rates of interest. An order of

751

states that because rich

farmers were lending rice and money to poor farmers at high interest

and were taking their fields and houses as security, many personal-

51 A wooden tablet (mokkan) dated 753 and excavated from the ruins of a fort at Akita shows

that produce taxes were being collected from vagrants. Farris believes that the 735-7 small-

pox epidemic had an important bearing on the government's decision to abandon the forced

escort of returning vagrants; see Population, Disease, and

Land,

pp. 121-35.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

POLICY CHANGES 445

share farmers were being forced to abandon their fields and flee to

neighboring provinces.'

2

Although the wording of the order prohibit-

ing such practices probably exaggerated the situation somewhat, it

does suggest that the problem was becoming quite serious.

Poor farmers included not only those who had failed to pay back

their loans and had lost their land but also vagrants who poured across

provincial borders to become privately employed laborers. At first,

these vagrants were not reported to governmental authorities by their

employers. The 736 policy of registering vagrants made it legal for

wealthy fanners to employ them. The resultant increase in the number

of vagrants widened the gap between rich and poor farmers,

a

problem

intertwined with the rapid increase in the number and size of loans.

Although some wealthy fanners were undoubtedly new to the game,

a majority were probably descendants of local gentry. A typical mag-

nate may have been Oya no Miyade, the district supervisor

{tairyo)

of

Miki District in Sanuki Province, who owned livestock, slaves, rice,

cash, rice paddies, and dry fields.^ Most of his slaves were probably of

the traditional type, but some were certainly vagrants. Oya's rice hold-

ings and money were clearly not obtained from agricultural activity

alone but were accumulated, in part at least, from loans of rice and

money at exorbitant rates of interest. Even his landholdings had un-

doubtedly been increased by loan foreclosures.

Loans made by wealthy farmers in local villages were only

a

part of a

larger financial picture. State loans made by provincial officials were

also a major source of

revenue.

As the

financial

situation of the

ritsuryo

state deteriorated, such income became increasingly important. Un-

like the land tax that might be reduced or even waived at times of poor

crops caused by drought or flood, a state loan was canceled only when

a peasant borrower died, making interest on loans a relatively stable

source of revenue. Thus as the government's financial needs in-

creased, the state loans became larger and more numerous.

The greater importance of state loans was paralleled by the govern-

ment's pressure on farmers to borrow. Although the original purpose

of state loans (to help poor farmers in times of need) had not been

forgotten, state loans took on the character of taxes to the extent that

peasants borrowed more than they needed. The number of rice loans

gradually increased after about 724, and the income from them was

probably enough to cover the operating costs of some provincial gov-

52 Shoku Nihongi, Enryaku 2 (783) 12/6, cites a council order of Tempyo Shoho 3 (751) 9/4, KT,

1.257-9. A ful] text of the order is in Ruiju sandai kyaku, KT 25.403-4.

53 Nihon ryoiki, NKBT 70.393-5, trans, in Nakamura,

Miraculous

Tales, pp. 257-9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

446 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

ernments. As a result of increasing their income from loans, various

provinces were able to store up a considerable amount of rice paid as

land tax

(denso).

Provincial governors were required to make yearly

reports on these receipts and on their use. Twenty-five such reports

(shozeicho)

for the decade between 729 and 739 have been preserved in

the Shoso-in in Nara.s* Of course this is only a small percentage of the

total submitted by various provinces during the eighth century, and

only fragments of the twenty-five extant ones remain. Nevertheless,

these fragments help explain the nature and volume of rice receipts

and expenditures at a time when state loans were becoming an impor-

tant source of revenue. According to rice storage reports from Owari

Province dating between 730 and 734, this province's assets in un-

hulled rice rose from 162,808 koku in 722, to 213,324

koku

in 730, and

to 258,440 koku in 733.ss During the eight years between 722 and 730

the rice revenue of Owari rose by 31 percent (an average increase of

3.43 percent per year) and between 730 and 733 by

21

percent, or 6.5

percent per year.

A report in 739 from the Bitchu Province reveals that both the

principal and interest on 127 loans were canceled that year because

forty-four borrowers had died.5

6

The cancellations totaled 6,479.7

sheaves

(soku).

Although the average was

51

sheaves per loan, the size

of the forty-four loans varied greatly. Most of the twenty-five smallest

ones were less than 20 sheaves each. At the higher range, however, the

loans were 142, 150, 172,174, 184, and 191 sheaves. Such large loans

could not possibly have been paid off in a single year, suggesting that

cancellations were made for persons who had defaulted on their loans

for several years. This leaves the impression that people were being

forced to borrow and that interest on loans had acquired the character

of tax revenue.

In 737 the government prohibited private lending.5? We do not

know to what extent this prohibition was enforced, but it is assumed

that it forced some farmers to turn from private to state loans in years

when these loans were becoming a vital source of state revenue. In the

tenth month of

745

the government also set limits on two kinds of state

loans:

the

rontei-to

and the

kuge-to.

The former were limited to an

amount fixed by the central government and were made by provincial

54 For a list of shozeicho fragments, see Hayakawa Shohachi, "Kuge-to seido no seiritsu,"

Shigaku zasshi 69 (March i960): 43-45; and Hayashi Rokuro and Suzuki Yasutami, eds.,

Fukugen

Tempyo shokoku shozeicho

(Tokyo: Gendai shichosha, 1985).

55 DaiNihonkomonjo, 1.413-17,607-20. TheMjraiiun contains

a sAdzeicAd

dated 734,1.215-21.

56 DaiNihonkomonjo, 2.247-52; Nara ibun, 1.316-19.

57 Shoku Nihongi Tempyo 9 (737) 9/22, KT 1.146.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008