The Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. 1: Ancient Japan

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

LAND TENURE 417

one-third as much as a male commoner; and a female slave, one-

third that of

a

female commoner.

2.

In regions without enough rice land to meet these requirements,

land was allocated in accordance with locally established formulas.

3.

Every six years, allocations were adjusted to the current size and

composition of each household. The year for readjustment (the

hannen)

usually came two years after a census had been taken.

4

4.

When an allotment holder died, his or her allotted land was re-

turned to the state at the time of the next

hannen.

In case all or part

of

a

household had fled to another province, or a person had been

killed in battle away from home, return of allotments was delayed.

5.

Allocated land could not be bought or sold, used as collateral for

loans,

inherited, or transferred to others. But renting

(chinso)

was

permitted if an annual notice thereof

was

submitted to the provin-

cial governor.

These elements of Japan's rice

field

allocation system had taken differ-

ent forms before the adoption of the Yoro code in 718.

When was the allocation system devised? According to the Nihon

shoki,

it was spelled out in an edict issued in the first month of 646.5

Scholars now feel, however, that the contents of the edict show that it

was written somewhat later. And yet the reform government may well

have tried to set up some kind of land system and to make an inventory

of

the

nation's paddy

fields

soon after

the 645

coup d'etat. Ishimoda Sho

takes

the position that a

field

distribution system

(fudensei)

- not includ-

ing reallocation - was established after 645. Supporting evidence for

this view is rather weak, but the logic of it is generally recognized.

6

Was the Omi code compiled during the reign of Tenji (661-71), and

were its provisions implemented? Various answers have been pro-

posed, but none has yet been generally accepted. If such a code did

exist, we do not know what kind of land system it outlined. My own

view is that something similar to the one detailed in the Taiho and

4 Little is known of the process by which provincial officials made land allotments, but the laws

required that household registration be started in the eleventh month of year A, that registra-

tion be completed by the fifth month of the following year B, and that an official land survey

be made in the tenth month of year B. Actual allocation was started in the eleventh month of

year B and completed by the second month of year C. In practice, surveys continued on into

the spring of year C. Thus the actual allocation of rice land was made between the winter of

year C and the spring of year D.

5 Nihon

shoki,

Kotoku 2 (646) 1/1, in Sakamoto Taro, Ienaga Saburo, Inoue Mitsusada, and Ono

Susumu, eds., Nihon koien bungaku taikei (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1967) (hereafter cited as

NKBT), vol 68, pp. 280-3; translated in W. G. Aston, Nihongi,

Chronicles

of Japan from the

Earliest

Times

to

A.D.

697 (London: Allen & Unwin, 1956), pt. 2-, pp. 206-10.

6 Ishimoda Sho, Nihon no kodai kokka (Tokyo: Iwanami shoten, 1971), pp. 318-21.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

418 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

Yoro codes first appeared in the Asuka no Kiyomihara administrative

code compiled late in Temmu's reign (672-86) and promulgated in

68<).

7

Nothing of this code remains. From indirect evidence we deduce

that its land allocation provisions differed from later formulations in

one important respect: All persons listed on a household register were

entitled to an allotment, and nothing apparently was said about alloca-

tions varying with the grantee's age. We have no definite proof that

everyone received shares of land, but an examination of allotments

made to households in northern Kyushu (an area for which we have

household registers for the year 702) suggests that all individuals re-

ceived shares, irrespective of age.

8

By the Taiho code of

701,

allotments were made only to persons

over the age of six, a change that may have resulted from a shortage of

arable land. But a more likely explanation is that the high rate of infant

mortality was forcing the government to reallocate land too often,

thereby creating heavy administrative burdens and management diffi-

culties. The Taiho code also reflected some change in the disposition

of land held by persons who died before the first reallocation, stipulat-

ing that such land did not have to be returned to the state at the time

of

the next reallocation, but six years later.' This exception was removed

in the later Yoro code, possibly because not enough land was available

for allocation.

Uniqueness

of Japan's allotment system

If

we

compare Japan's allotment system of about 718 with the Chinese

model, we find important differences. Adapted somewhat to divergent

economic and social conditions, Japan's systems contained the follow-

ing unique features:

1.

In China an allotment was valid for a fixed number of years and

made the allotment holder responsible for paying taxes. But in

Japan allotments were not linked directly with the obligation to pay

7 Torao, Handen shuju ho no kenkyu, pp. 53-80. For alternative views, see Kishi Toshio, Nihon

kodai

sekicho

no kenkyu (Tokyo: Hanawa shobo, 1973), pp.

73-81;

and Miyahara Takeo, Nikon

kodai no kokka to

nomin

(Tokyo: Hdsei University Press, 1973), pp. 164-211. For my rebuttal,

see Torao Toshiya, Nihon kodai

tochi ho shiron

(Tokyo, Yoshikawa kobunkan, 1981), pp. 50-101.

8 These household registers are published in Tokyo daigaku shiryo hensanjo, ed., Dai Nihon

komonjo:

hennen

no bu (Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1901-40), vol. I, pp. 97-218; and in

Takeuchi

RKO,

ed., Nara ibun (Tokyo: Tokyodo shuppan, 1962), vol. 1, pp. 86-134.

9 Because only fragments of the Taiho code have been preserved, no single view has been

generally accepted. The Taiho fragments are in the Ryo no

shuge,

KT, 23.363. For a more

recent interpretation, see Torao,

Nihon

kodai

tochi

ho

shiron,

pp. 120-52.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

LAND TENURE 419

taxes.

10

The Taiho code provided for allotments to every individual

over the age of six, but tax obligations were not governed by age.

2.

In pre-T'ang China the only female commoners to receive allot-

ments were married women, and they were explicitly required to

pay taxes. During T'ang times, no female was entitled to an allot-

ment. But in Japan all women commoners over the age of

six

were

allotted two-thirds as much land as a male commoner was, and no

mention was made of tax obligations.

3.

The law of pre-T'ang dynasties called for allotments of land to

slaves who were required to pay taxes, like commoners. But in

Japan a slave received one-third as much land as a commoner did,

and the law said nothing about his having to paying taxes.

These differences can be explained by the tendency of Chinese laws to

hold the head of the household responsible for the payment of a poll

tax, whereas Japanese law did not. In Japan, officials seemed to rely

mainly on households for the collection of taxes, and attempts were

made to supply these households, through allotments to individual

members, with enough land to sustain the life of each person. Conse-

quently, there was a rough correlation among the size of

a

household,

the amount of land allotted to its members, and the tax burden.

Two types of taxes existed for a few decades after the Great Reform

of

645:

(1) a tax levied on each household, irrespective of the number,

sex, age, and social position of its members and (2) a tax on land

according to its size. After promulgation of the Asuka no Kiyomihara

code in 689, Japan's tax system tended to shift from what was essen-

tially a household tax to something like the Chinese poll tax, but the

core of Japan's allotment system remained, leaving no direct linkage

between allotments and taxes.

Nonallotted landholdings

Land left after allotments had been made was designated as surplus

land

(joderi)

and placed under the jurisdiction of provincial governors

who rented

(chinso)

it to farmers holding land allotments. This practice

was not unlike the tenancy

(kosaku)

system that prevailed in Japanese

farming villages before World War II. In both cases paddy land was

rented to farmers in return for rent paid in kind. In Nara times this

10 Strictly speaking, land allotment and tax in pre-T'ang China were not perfectly joined, as a

corvee exemption tax was not levied on female grantees of land during pre-T'ang dynasties.

Only during the T'ang period, when women received no land and paid no taxes, were the two

perfectly joined.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

420

NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

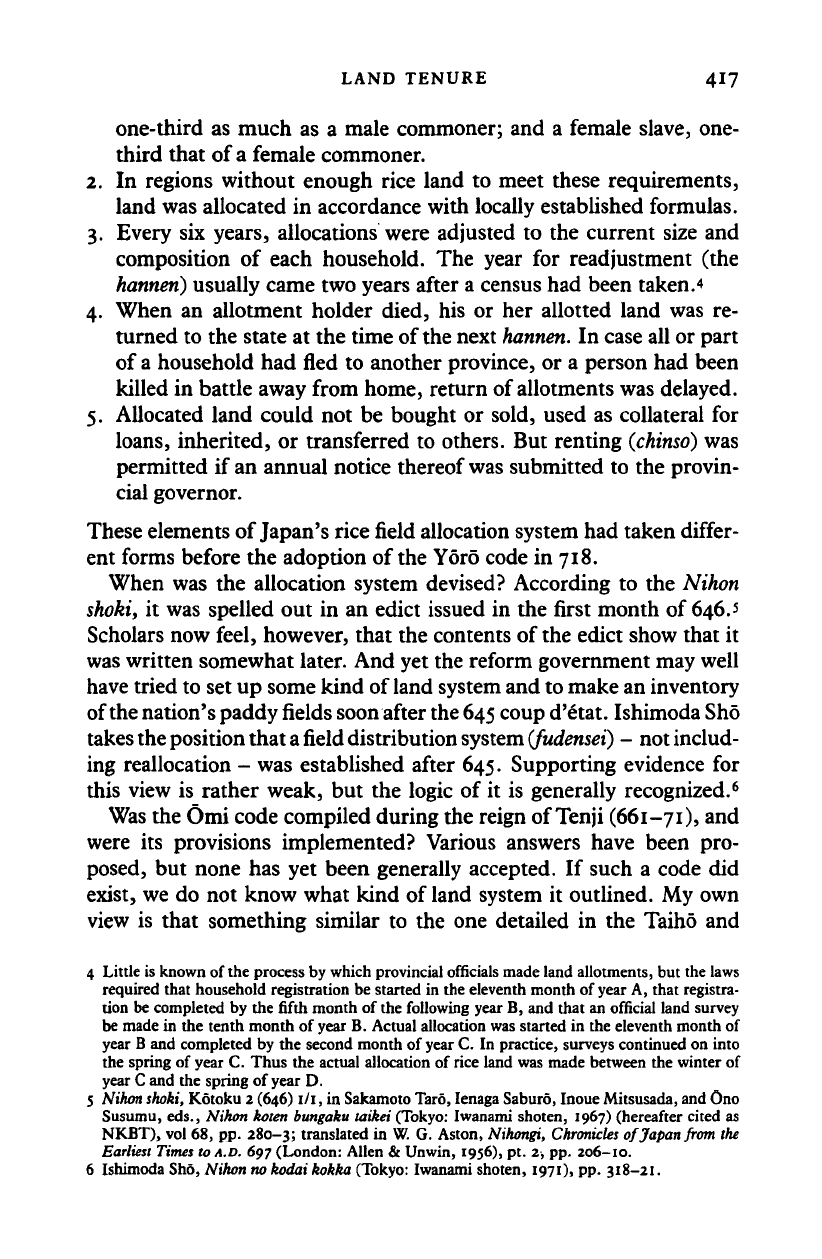

Type

Imperial domains"

(kanden) (londen)

Rank land (iden)

Temple land (jiden)

Shrine land

(shinderi)

Station land (ekiden)

Merit land' (koden)

Imperially bestowed

land (shiden)

Office land

(shikibunden):

Central (shikidenY

Provincial

(kugedetif

District (shikiden)

TABLE 8.

I

Nonalbtment holdings

Grantee

Emperor or em-

press

Holders of the fifth

rank and above

Buddhist temples

Shinto shrines

Stations on the offi-

cial transport

system

Meritorious

individuals

Recipients named

in an edict

Major counselors

and above

Dazaifu and provin-

cial officials

District officials

How worked

Corvee labor

Rental (chinso)

Slavery, hired labor,

rental

Slavery, hired labor,

rental

Rental

Rental

Rental

Rental

Worked by servants

at state expense

Rental, or family

labor

Taxes

None

Land tax

None

None

None

Land tax

Land tax

None

None

Land tax

"A term used in the Taiho code.

'This type could be passed on to the next generation and even longer, for greater degrees of

merit.

took two forms: an amount of rent

(chin)

paid to the provincial gover-

nor before planting or an amout of rice

(so)

handed over after harvest.

The latter was generally preferred. It is estimated that a fanner work-

ing surplus land had to pay, as

chin

or

so,

about 20 percent of his crop.

The provincial governors who received the rent were required to for-

ward it to the Council of State in the capital, where it was used to

defray administrative expenses.

Other types of nonallotted land included grants to the emperor,

court nobles, government officials, temples and shrines, and meritori-

ous individuals. The character of such grants, as set forth in the Yoro

code,

is outlined in Table 8.1. Note that all nonallotment holdings,

except those held directly by the emperor, were rented to persons who

paid a fixed amount of rice as rent.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

LAND TENURE

421

jo I

jo 2

jo 3

jo 4

rt 1

s

CJ

W2

•"—

6

cho

—•

one

ri

n i

.one

tsubo

T

ri4

^No.

1

tsubo

of

4th

;o,

4th ri

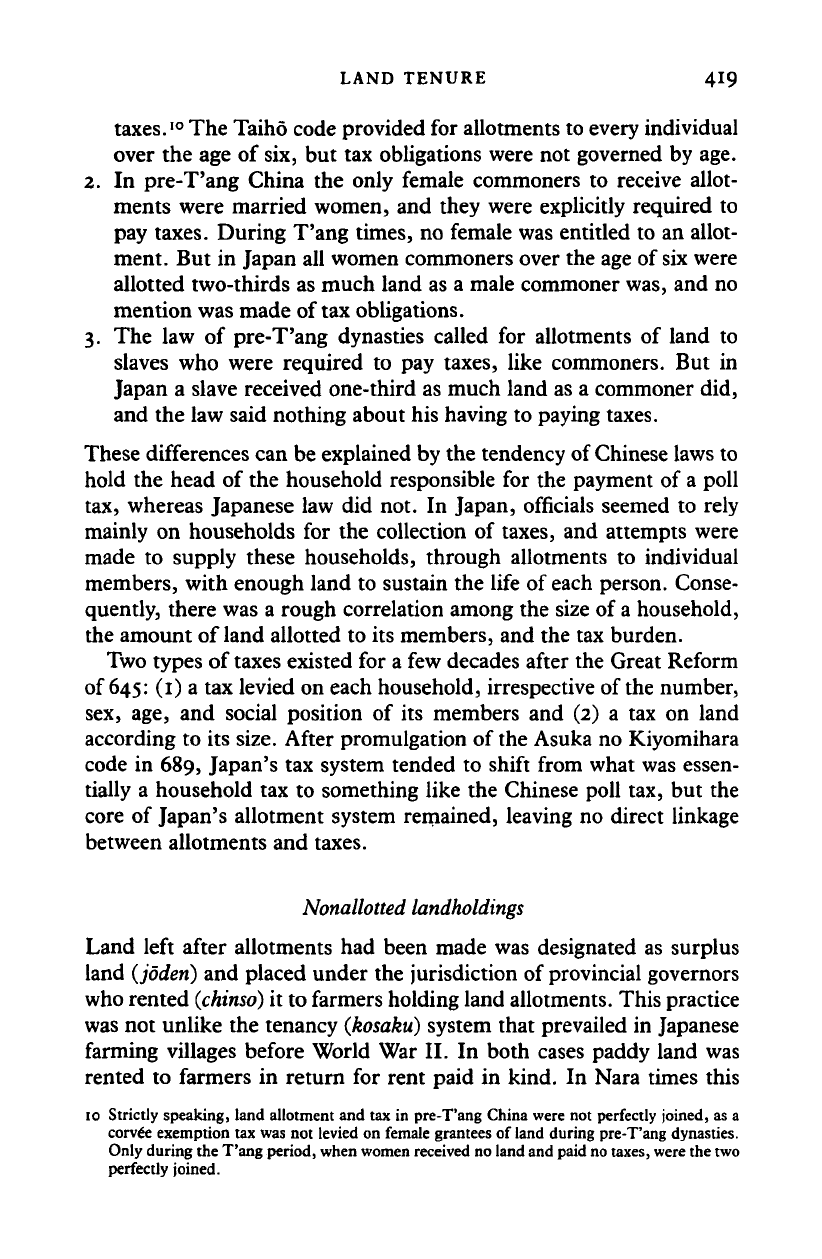

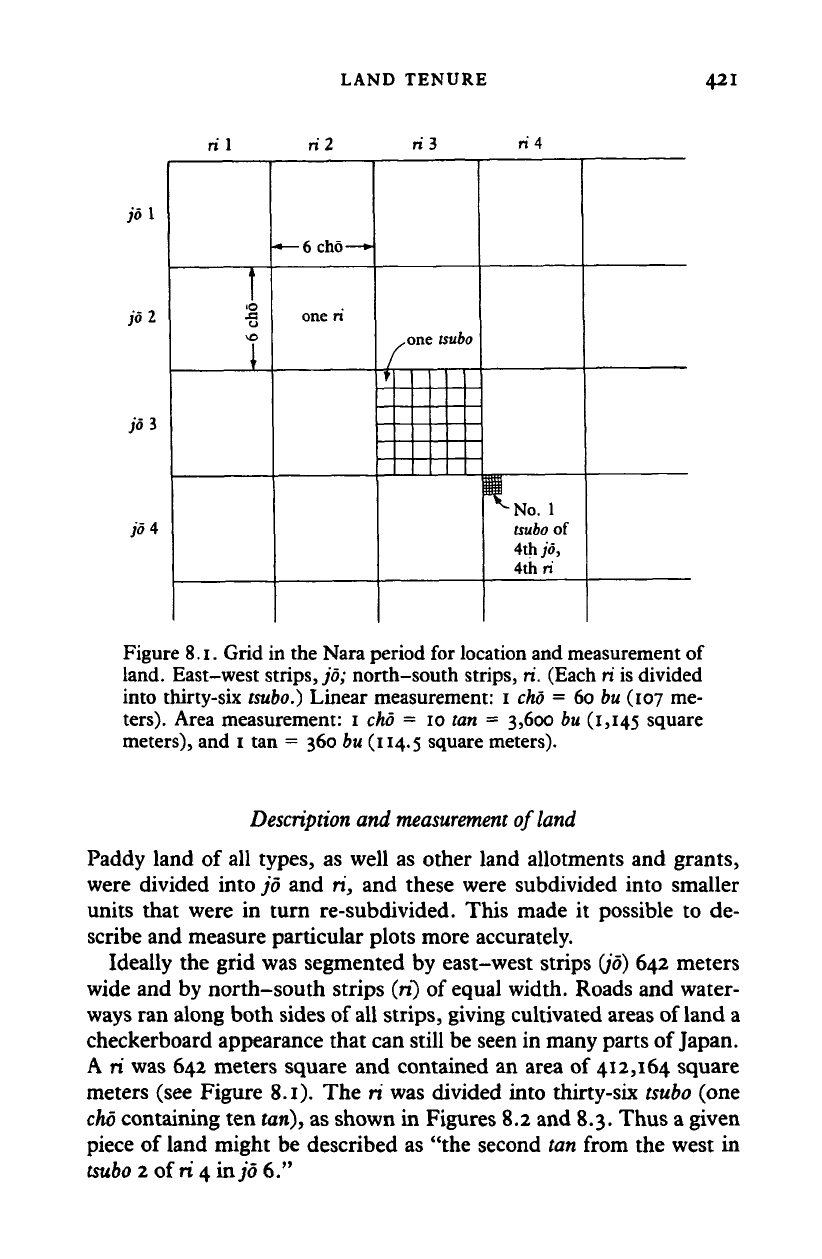

Figure 8.1. Grid in the Nara period for location and measurement of

land. East-west strips, jo; north-south strips,

ri.

(Each ri is divided

into thirty-six

tsubo.)

Linear measurement: 1

cho

= 60 bu (107 me-

ters).

Area measurement: 1 cho - 10 tan = 3,600 bu (1,145 square

meters), and

1

tan = 360 bu (114.5 square meters).

Description and

measurement

of land

Paddy land of all types, as well as other land allotments and grants,

were divided into jo and ri, and these were subdivided into smaller

units that were in turn re-subdivided. This made it possible to de-

scribe and measure particular plots more accurately.

Ideally the grid was segmented by east-west strips

(jo)

642 meters

wide and by north-south strips

(rt)

of equal width. Roads and water-

ways ran along both sides of all strips, giving cultivated areas of land a

checkerboard appearance that can still be seen in many parts of Japan.

A ri was 642 meters square and contained an area of 412,164 square

meters (see Figure 8.1). The ri was divided into thirty-six

tsubo

(one

cho

containing ten tan), as shown in Figures 8.2 and 8.3. Thus a given

piece of land might be described as "the second tan from the west in

tsubo

2 of ri 4 injd 6."

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

422

NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

The

chidori

system

The

heiko

system

1

2

3

4

5

6

12

11

10

9

8

7

13

14

15

16

17

18

24

23

22

21

20

19

25

26

27

28

29

30

36

35

34

33

32

31

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

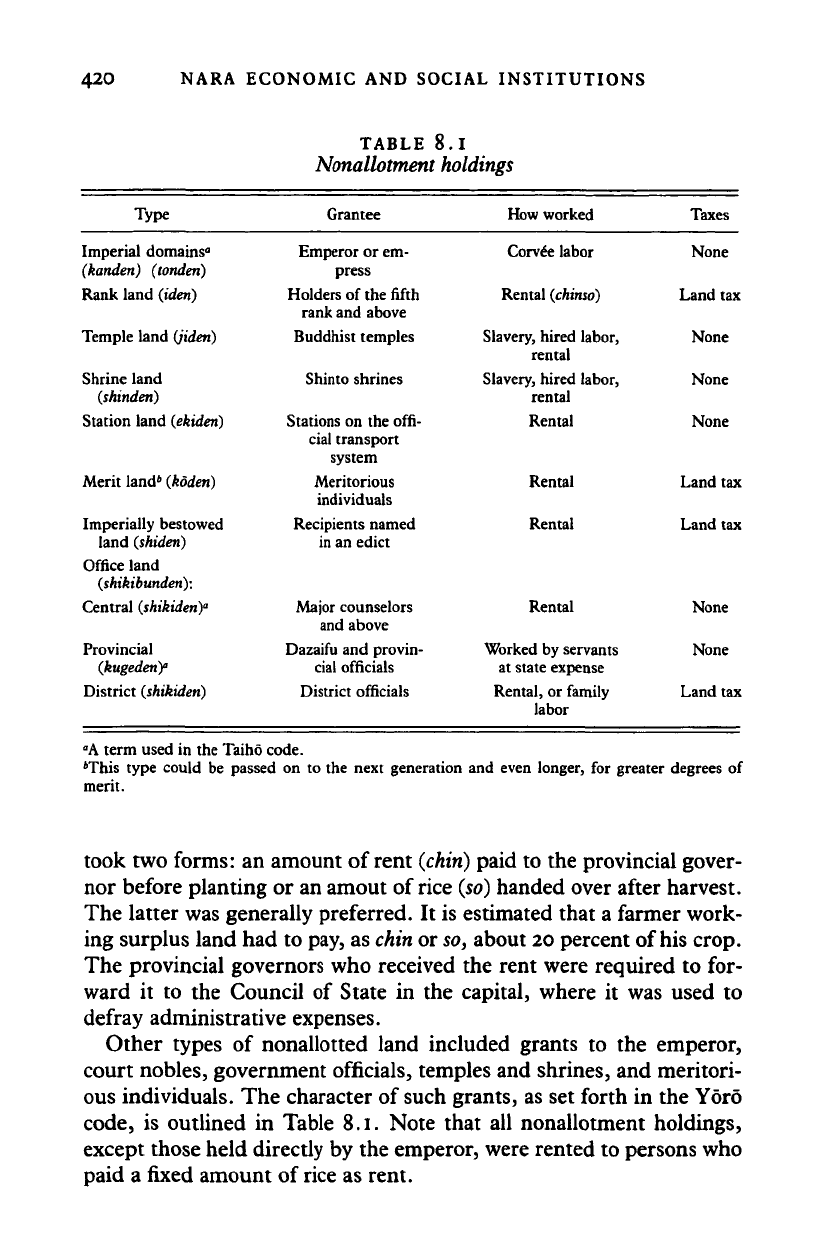

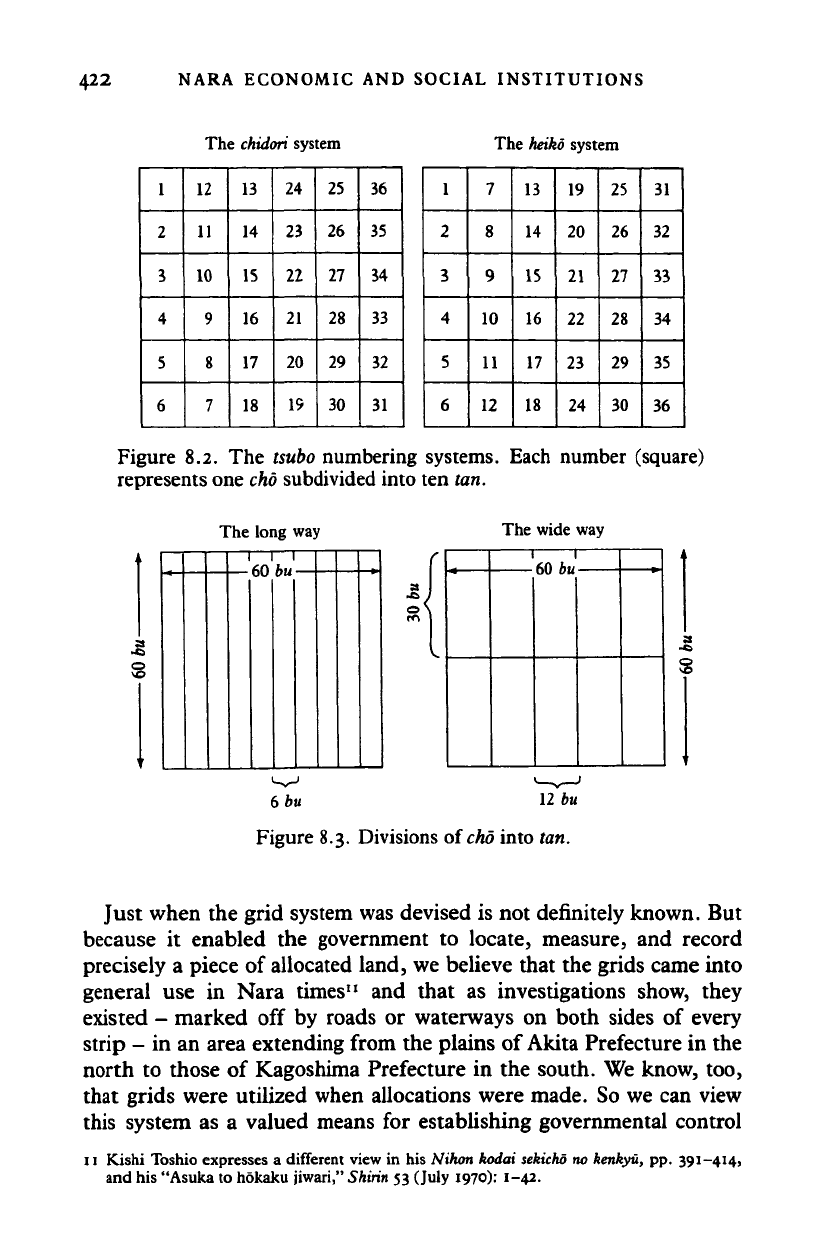

Figure

8.2. The

tsubo

numbering systems. Each number (square)

represents one

cho

subdivided into ten tan.

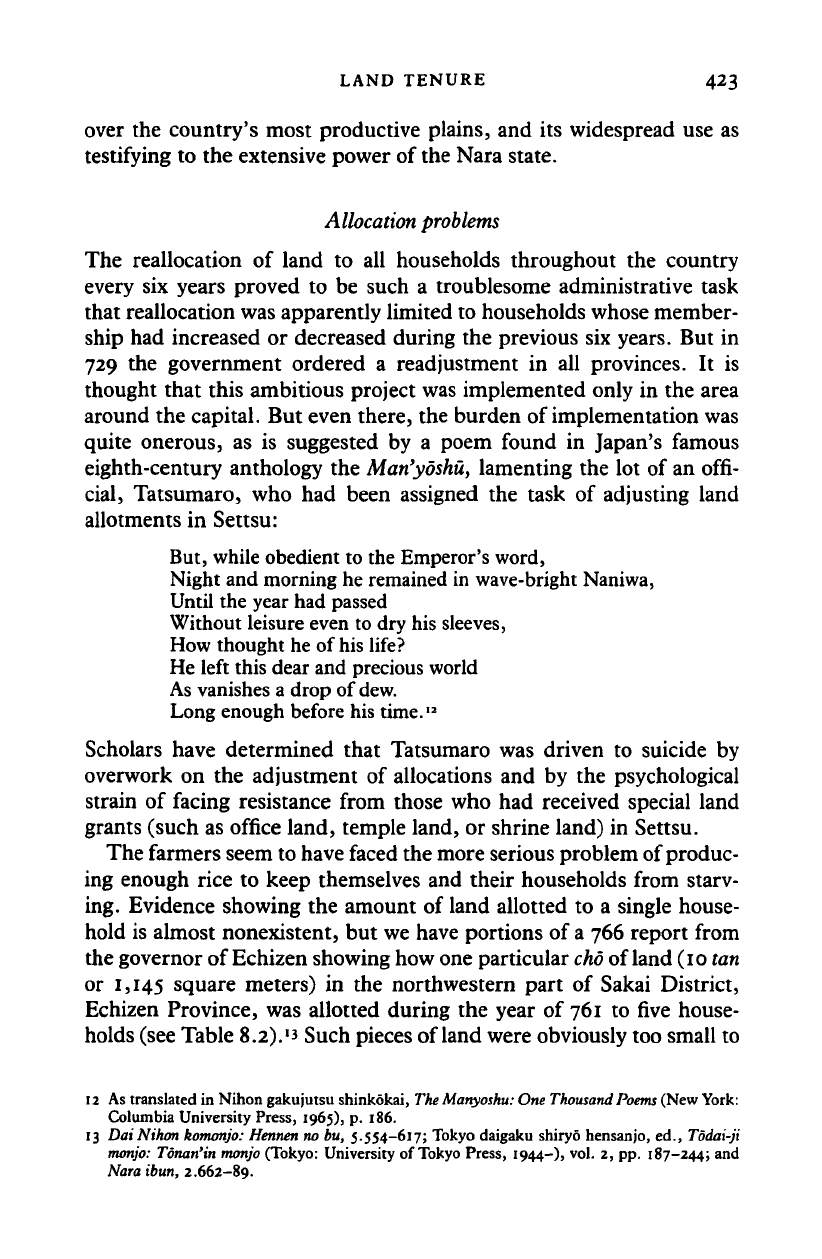

The long way

-60 b

The

wide

60 bu

way

6 bu

12 bu

Figure 8.3. Divisions of

cho

into tan.

Just when the grid system was devised

is

not definitely known.

But

because

it

enabled

the

government

to

locate, measure,

and

record

precisely

a

piece

of

allocated land, we believe that the grids came into

general

use in

Nara times"

and

that

as

investigations show, they

existed

-

marked

off by

roads

or

waterways

on

both sides

of

every

strip

- in an

area extending from the plains

of

Akita Prefecture

in the

north

to

those

of

Kagoshima Prefecture

in the

south. We know,

too,

that grids were utilized when allocations were made. So we can view

this system

as a

valued means

for

establishing governmental control

11 Kishi Toshio expresses

a

different view

in his

Nihon kodai

sekicho

no kenkyu,

pp.

391-414,

and

his

"Asuka

to

hokaku jiwari," Shirin

53

(July 1970):

1-42.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

LAND TENURE 423

over the country's most productive plains, and its widespread use as

testifying to the extensive power of the Nara state.

Allocation

problems

The reallocation of land to all households throughout the country

every six years proved to be such a troublesome administrative task

that reallocation was apparently limited to households whose member-

ship had increased or decreased during the previous six years. But in

729 the government ordered a readjustment in all provinces. It is

thought that this ambitious project was implemented only in the area

around the capital. But even there, the burden of implementation was

quite onerous, as is suggested by a poem found in Japan's famous

eighth-century anthology the Man'yoshu, lamenting the lot of an offi-

cial, Tatsumaro, who had been assigned the task of adjusting land

allotments in Settsu:

But, while obedient to the Emperor's word,

Night and morning he remained in wave-bright Naniwa,

Until the year had passed

Without leisure even to dry his sleeves,

How thought he of

his

life?

He left this dear and precious world

As vanishes a drop of dew.

Long enough before his time.

12

Scholars have determined that Tatsumaro was driven to suicide by

overwork on the adjustment of allocations and by the psychological

strain of facing resistance from those who had received special land

grants (such as office land, temple land, or shrine land) in Settsu.

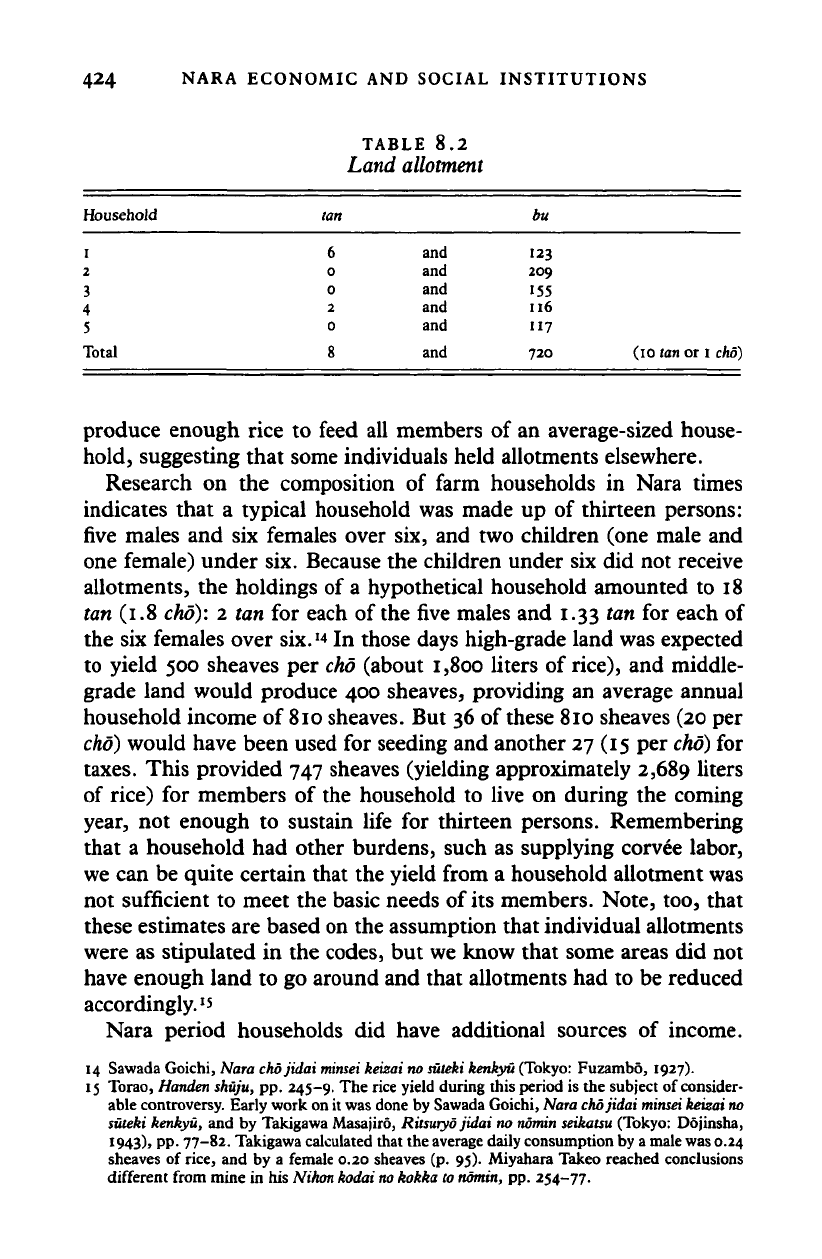

The farmers seem to have faced the more serious problem of produc-

ing enough rice to keep themselves and their households from starv-

ing. Evidence showing the amount of land allotted to a single house-

hold is almost nonexistent, but we have portions of a 766 report from

the governor of Echizen showing how one particular

cho

of land (10 fan

or 1,145 square meters) in the northwestern part of Sakai District,

Echizen Province, was allotted during the year of 761 to five house-

holds (see Table

8.2).'3

Such pieces of land were obviously too small to

12 As translated in Nihon gakujutsu shinkokai,

The

Manyoshu:

One

Thousand Poems

(New York:

Columbia University Press, 1965), p. 186.

13 Dai Nihon

komonjo:

Hennen

no bu, 5.554-617; Tokyo daigaku shiryo hensanjo, ed., Todai-ji

monjo:

Tonan'in

monjo

(Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1944-), vol. 2, pp. 187-244; and

Nara ibun, 2.662-89.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

424 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

TABLE 8.2

Land allotment

Household tan bu

1 6 and 123

2 o and 209

3 o and 155

4 2 and 116

5 0 and 117

Total 8 and 720 (10 tan or 1 cho)

produce enough rice to feed all members of an average-sized house-

hold, suggesting that some individuals held allotments elsewhere.

Research on the composition of farm households in Nara times

indicates that a typical household was made up of thirteen persons:

five males and six females over six, and two children (one male and

one female) under six. Because the children under six did not receive

allotments, the holdings of a hypothetical household amounted to 18

tan (1.8

cho):

2 tan for each of the five males and 1.33 ton for each of

the six females over six.

14

In those days high-grade land was expected

to yield 500 sheaves per

cho

(about 1,800 liters of rice), and middle-

grade land would produce 400 sheaves, providing an average annual

household income of 810 sheaves. But 36 of these 810 sheaves (20 per

cho)

would have been used for seeding and another 27 (15 per

cho)

for

taxes.

This provided 747 sheaves (yielding approximately 2,689 liters

of rice) for members of the household to live on during the coming

year, not enough to sustain life for thirteen persons. Remembering

that a household had other burdens, such as supplying corvee labor,

we can be quite certain that the yield from a household allotment was

not sufficient to meet the basic needs of its members. Note, too, that

these estimates are based on the assumption that individual allotments

were as stipulated in the codes, but we know that some areas did not

have enough land to go around and that allotments had to be reduced

accordingly.

1

'

Nara period households did have additional sources of income.

14 Sawada Goichi, Nara chojidai

minsei

keizai no

suteki

kenkyu (Tokyo: Fuzambd, 1927).

15 Torao, Handen shuju, pp. 245-9. The rice yield during this period is the subject of consider-

able controversy. Early work on it was done by Sawada Goichi, Nara chojidai

minsei

keizai

no

suteki kenkyu, and by Takigawa Masajiro, Ritsuryo jidai no

nomin

seikatsu (Tokyo: Dojinsha,

1943),

pp. 77-82. Takigawa calculated that the average daily consumption by a male was 0.24

sheaves of rice, and by a female 0.20 sheaves (p. 95). Miyahara Takeo reached conclusions

different from mine in his Nikon kodai

no

kokka to

nomin,

pp. 254-77.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTROL OF PERSONS 425

Land could be rented from other farmers or from government offi-

cials,

and household members might turn to slash-and-burn agricul-

ture or to the dry farming of millet, barley, or wheat. An increasing

body of evidence suggests that such secondary occupations as fishing

and forestry also served to supplement a family's income, as did hunt-

ing and gathering. But such gains probably did not offset the losses

caused by drought and storm. The Shoku

Nihongi

(a court chronicle of

the eighth century) reports poor crops in one section or another of

Japan almost every year. So the income of a household was not only

meager but also unstable, making the lot of

a

Nara farmer a harsh one

indeed.

16

CONTROL OF PERSONS

The people of Nara Japan were classified by law as commoners

(ryomin)

or slaves

(semmin).

Laws prohibited a person from marrying

outside his or her class and prescribed much more severe punishments

for crimes committed by slaves. But slaves made up less than 10

percent of the population and were not the country's main producers.

Slaves

The slave class was divided by law into five subgroups according to

types of ownership and degrees of freedom. The first subgroup was

state slaves (kanko) owned by the central government. They could

have families and could use a portion of their labor for themselves.

The second subgroup was private slaves

(ke'niti)

owned by common-

ers.

They had as much freedom as did state slaves. The third was,state

chattel slaves

(kunuhi)

owned by the central government. They were

treated as property that could be bought and sold. The fourth sub-

group was private chattel slaves

(shinuht)

owned by commoners. They

were otherwise treated like state chattel slaves. And the fifth was the

imperial-mausolea slaves

{ryoko)

owned by officials. They were used to

protect and maintain the tombs of deceased emperors and empresses.

Private slaves

(ke'nin)

are not mentioned in extant household regis-

ters or other records of the eighth century, and we find only scattered

references to them in legal provisions of that and the following centu-

16 William Wayne Farris concluded that epidemics and inadequate irrigation technology drove

the peasants from their land and created unsettled farming conditions; see his Population,

Disease, and Land in Early Japan, 645-900

(Harvard—Yenching Monograph

Series no. 24)

(Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1985), pp.74-117.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

426 NARA ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS

ries.

We therefore assume that private slaves were not numerous and

that imperial-mausolea slaves were ranked about as high as common-

ers were, as they were despised only because of the work they did.

Commoners, on the other hand, included artisan groups

(shinabe)

that

were much like slaves. The largest slave subgroup was private chattel

slaves, who were owned mainly by temples, shrines, public officials,

and wealthy farmers. One private chattel

slave,

according to contempo-

rary sources, had roughly the value of

a

strong horse or cow.'7

Holders

of court rank

Commoners were divided between those who held court ranks and

those who did not, roughly between the rulers and the ruled. There

was some mobility between the two groups, but the legal distinctions

were clear and significant.

Holders of court ranks held public office, the highest posts being

reserved for those with

the

highest rank. These favored commoners did

not simply occupy positions of political control but also obtained in-

comes appropriate to their rank and office. They were

also

exempt from

all taxes, except those levied on land grants accompanying the conferral

of rank or office. When convicted of a crime, they received lighter

sentences and were allowed less onerous ways of serving sentences.

Holders of court rank were, in turn, divided between elite court-

connected aristocrats who held the top fourteen ranks (senior first

rank through junior fifth rank lower grade) of the thirty defined by

law, and lower-ranking nobles who held the bottom sixteen ranks

(senior sixth rank upper grade through lesser bottom rank lower

grade).

All the holders of the highest fourteen ranks were men born

into a few powerful uji (clans) associated with the court, blocking all

others from positions of effective political control. This elite group

numbered no more than 250 in a population of between 5 million and

6 million. At the upper level were a few persons who monopolized the

highest six ranks of junior third rank and above, held the highest

offices, and received the most favored treatment. If one of these aristo-

crats were senior second rank (third from the top) and held the post of

minister of the left, he would be entitled to 60

cho

of land for his rank,

30

cho

for his office, and 2,200 households (200 for his rank and 2,000

for his office). He also received extra spring and fall stipends and used

17 For additional detail, see Takigawa Masajiro, Ritsuryo

semminsei no kenkyu

(Tokyo: Kadokawa

shoten, 1967).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008