The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE PEKING GOVERNMENT 263

beginning of practice; doing is the completion of knowledge.' As Sun

Yat-sen succinctly put it, 'Whatever can be known can certainly be carried

out.'

10

That is, if the conscious mind can be set straight as to how to do a

thing, the actual doing of it will be relatively unproblematical. Correla-

tively, if a thing is being done wrong, the solution lies in correcting the

conscious thoughts of the doer. Let the provisions of the constitution be

regarded as the thing 'known' by the conscious national mind, and there

is no reason a constitutional republic should not work. If it fails, the

reason must be either imperfect mastery of and commitment to its princi-

ples,

or flaws in the constitutional instrument

itself.

If consistency with this 'voluntarist' tradition helped make constitu-

tionalism plausible, its expected contribution to national wealth and power

made it positively attractive. In Chinese eyes, a constitution's function

was to connect the individual's interests with those of the state, thus

arousing the people to greater effort and creativity on behalf of national

goals.

The trouble with old China, many Chinese thinkers believed,

was the passivity and narrow selfishness of the people. In a modern state,

on the other hand, because the people rule, they devote themselves whole-

heartedly to the nation. When there are 'ten thousand eyes with one sight,

ten thousand hands and feet with only one mind, ten thousand ears with

one hearing, ten thousand powers with only one purpose of life; then the

state is established ten-thousandfold strong. . . . When mind touches

mind, when power is linked to power, cog to cog, strand around strand,

and ten thousand roads meet in one center, this will be a state.'" This

theme of constitution as energizer was linked with the Mencian notion

that, in Paul Cohen's paraphrase, 'just policies and causes command

popular support', and 'a ruler with popular support is invincible'."

Constitutionalism could be seen as such a just policy. The popular sup-

port it could command would provide the key to wealth and power for

China.

THE PEKING GOVERNMENT

For most of the 1916-28 period, the Peking government operated on

the basis of the Provisional Constitution of 1912. Although intended by

its architects to lodge predominant power in the cabinet, the Provisional

10 Confucius quoted in Nathan,

Peking

polities, 21; Wang Yang-ming in David S. Nivison,

'The problem of "knowledge" and "action" in Chinese thought since Wang Yang-ming',

in Arthur F. Wright, ed. Studies in

Chinese

thought,

120; Sun Yat-sen in Teng Ssu-yii and

John K. Fairbank, comps.

China's response

to the West: a

documentary

survey,

1839-192}, 264.

11 Liang Ch'i-ch'ao, quoted in Hao Chang, Liang

Ch'i-cHao

and

intellectual transition

in China,

1890-1907, 100.

12 Paul A. Cohen, 'Wang T'ao's perspective on a changing world', in Albert Feuerwerker,

Rhoads Murphey, and Mary C. Wright, eds. Approaches to

modern Chinese

history,

160.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE PEKING GOVERNMENT, I 9 I 6-2 8

Constitution was sufficiently ambiguous

to

encourage continuous con-

flict among president, prime minister and parliament.

The president, elected

by

parliament

for a

five-year term,

had the

symbolic functions and potentially the prestige

of a

head

of

state;

his

personality and factional backing determined whether he could translate

these into real power. The cabinet was supposed to 'assist' the president

by running ministries, co-signing presidential orders and enactments, and

answering questions

in

parliament; usually composed

by a

division

of

spoils among factions, the cabinet

in

fact rarely functioned as

a

policy-

making unit. The prime minister, despite

a

lack of specifically designated

constitutional powers, could sometimes dominate government through

his role

in

picking

a

cabinet and piloting its ratification through parlia-

ment, and by virtue of his control, through members of his own faction,

of such crucial ministries as army, finance, communications and interior.

Finally, parliament, composed

of a

house

and

senate whose members

enjoyed three- and six-year terms respectively, had powers not only

to

elect the president and vice-president and

to

ratify

the

cabinet,

but to

approve budgets, declarations of war and treaties, and to interpellate and

impeach. Often factionally disunified, and performing

a

relatively unfa-

miliar part in Chinese government, parliament was rarely able to act more

than passively

or

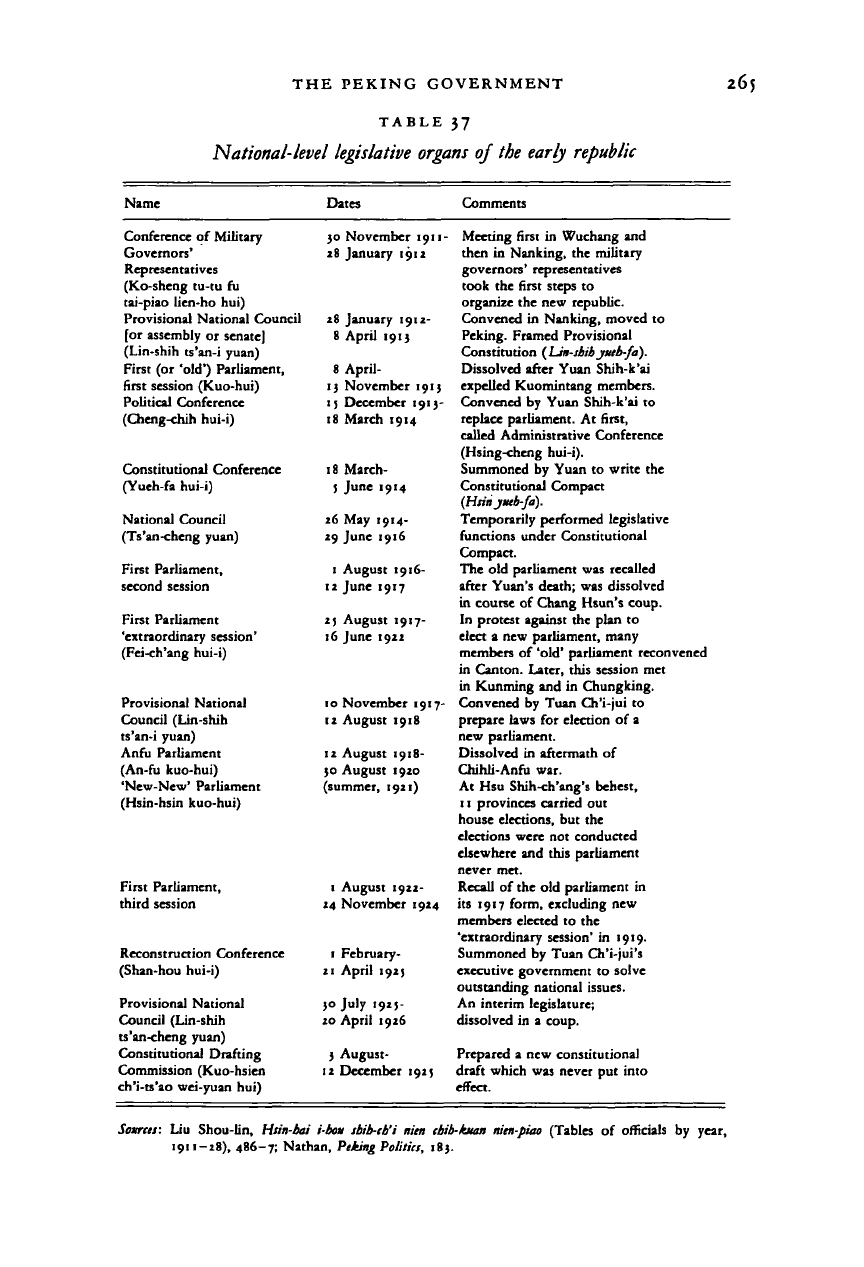

obstructively. Table 37 lists the parliaments and other

national-level legislative organs of the early republic.

Under the Provisional Constitution, parliament's major duty was

to

write

a

permanent constitution. Over

the

years successive legislatures

worked at this task, returning to many of the issues raised in late Ch'ing

debates and during the reign of Yuan Shih-k'ai

-

centralism versus local

self-government, legislative versus executive power,

and

broad versus

narrow political participation (see chapter 4).

A

good deal

of

time was

spent in the 1913-14 session preparing

a

draft constitution, and the work

was resumed in the 1916-17 session. In 1917 two governments came into

existence, one in Peking and one in Canton, each claiming to carry out the

Provisional Constitution, and each working

on a

constitutional draft.

Finally, when the original (or so-called 'old') parliament reconvened

in

1922,

it produced the 'Ts'ao K'un Constitution' (so called because

it

was

promulgated by President Ts'ao K'un)

of

10 October 1923. After

a

coup

d'etat drove Ts'ao from office in 1924, a temporary document, the Regula-

tions

of

the Chinese Republican Provisional Government, replaced

the

constitution, while

a

constitutional drafting commission was convened to

try again. Chang Tso-lin's regime

of

1927-28 provided itself with a docu-

ment

in

lieu

of a

constitution, the Mandate

on

the Organization

of

the

Marshal's Government.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE PEKING GOVERNMENT

265

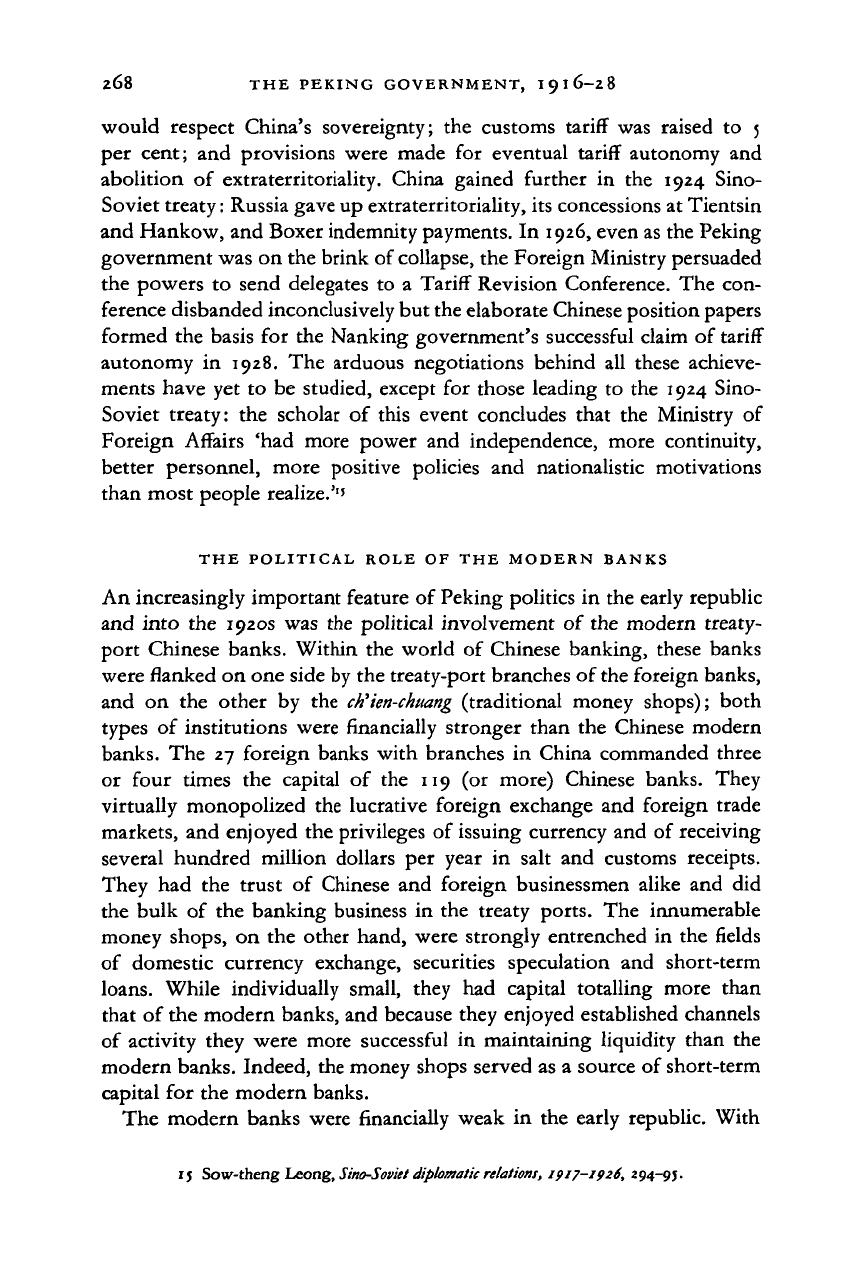

TABLE 37

National-level

legislative organs

of the early republic

Name Dates

Comments

Conference of Military

Governors*

Representatives

(Ko-sheng tu-tu fu

tai-piao lien-ho hui)

Provisional National Council

[or assembly or senate]

(Lin-shih ts'an-i yuan)

First (or 'old') Parliament,

first session (Kuo-hui)

Political Conference

(Cheng-chih hui-i)

Constitutional Conference

(Yueh-fa hui-i)

National Council

(Ts'an-cheng yuan)

First Parliament,

second session

First Parliament

'extraordinary session'

(Fei-ch'ang hui-i)

Provisional National

Council (Lin-shih

ts'an-i yuan)

Anfu Parliament

(An-fu kuo-hui)

'New-New' Parliament

(Hsin-hsin kuo-hui)

First Parliament,

third session

Reconstruction Conference

(Shan-hou hui-i)

Provisional National

Council (Lin-shih

ts'an-cheng yuan)

Constitutional Drafting

Commission (Kuo-hsien

ch'i-ts'ao wei-yuan hui)

30 November 1911- Meeting first in Wuchang and

28 January 1912 then in Nanking, the military

governors' representatives

took the first steps to

organize the new republic.

28 January 1912- Convened in Nanking, moved to

8 April 1913 Peking. Framed Provisional

Constitution (Ua-sbib

jueb-fa).

8 April- Dissolved after Yuan Shih-k'ai

13 November 1913 expelled Kuomintang members.

1;

December 1913- Convened by Yuan Shih-k'ai to

18 March 1914 replace parliament. At first,

called Administrative Conference

(Hsing-cheng hui-i).

18 March- Summoned by Yuan to write the

t June 1914 Constitutional Compact

(Hsiri

jneb-fa).

26 May 1914- Temporarily performed legislative

29 June 1916 functions under Constitutional

Compact.

1 August 1916- The old parliament was recalled

12 June 1917 after Yuan's death; was dissolved

in course of Chang Hsun's coup.

2;

August 1917- In protest against the plan to

16 June 1922 elect a new parliament, many

members of 'old* parliament reconvened

in Canton. Later, this session met

in Kunming and in Chungking.

10 November 1917- Convened by Tuan Ch'i-jui to

12 August 1918 prepare laws for election of a

new parliament.

12 August 1918- Dissolved in aftermath of

30 August 1920 Chihli-Anfu war.

(summer, 1921) At Hsu Shih-ch'ang's behest,

11 provinces carried out

house elections, but the

elections were not conducted

elsewhere and this parliament

never met.

1 August 1922- Recall of the old parliament in

24 November 1924 its 1917 form, excluding new

members elected to the

'extraordinary session' in 1919.

1 February- Summoned by Tuan Ch'i-jui's

21 April 192} executive government to solve

outstanding national issues.

30 July 192)- An interim legislature;

20 April 1926 dissolved in a coup.

3 August- Prepared a new constitutional

12 December 192) draft which was never put into

effect.

Sources:

Liu Shou-lin, Hsin-bai i-bou sbib-tb'i nien

chih-kuan nien-piao

(Tables of officials by year,

1911-28), 486-7; Nathan, Peking Politics, 185.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

266 THE PEKING GOVERNMENT, 1916-28

To the end of

its

life, the Peking government held a claim to legitimacy

which made

it

important even

in a

nation increasingly dominated

by

contending warlords. Until 1923,

if

not later, many leaders

of

public

opinion, while deploring the feuding and corruption of politicians, voiced

hope

in the

ultimate success

of the

constitutional order. Each major

warlord supported factional allies

or

followers

in

parliament, cabinet,

or the political press, and

if

possible cultivated good relations with the

prime minister and president. Often the aim was to gain official appoint-

ment (for example, as the governor of

a

province) to legitimize local rule.

A second reason

for

Peking's importance was foreign recognition.

Against

all

evidence

of

fragmentation, the foreign powers insisted that

there was only one China and

- as

late

as

1928

-

that

its

capital was

Peking. The powers generally insisted that formal settlement of issues go

through the central Ministry

of

Foreign Affairs, even

if

the case was es-

sentially local

in

scope. The many appointments

to

lucrative posts

in

railway and treaty-port offices also needed Peking's acquiescence even

if they were located

in

areas

of

warlord control, because they often in-

volved foreign interests. Finally,

the

presence

of

the foreign legations

afforded some physical protection to the city: although the privilege was

not invoked during the period, the Boxer Protocol

of

1901 provided

in

effect that warlord invasion

of

Peking

or

seizure

of

the Peking-Tientsin

railway might bring foreign military intervention.

A third source

of

Peking's influence was financial. Taxes played but

a

small role

in

Peking's finances; remittances began to decline even before

Yuan Shih-k'ai's death

and

shrivelled

to

insignificance thereafter.

Far

more significant was the financial consequence of foreign recognition: the

ability

to

borrow. The government borrowed abroad

on

the pledge

of

China's natural resources, as

in

the 140 million yen 'Nishihara loans'

of

1917-18.

And

it

borrowed at home

-

Ch.$63i million in 27 bond issues

from I9i3toi926-in part on the security

of

the salt gabelle and Mari-

time Customs Administration revenues which were shielded from warlord

interference

by

the powers' involvement

in

their collection (more fully

so in the case of customs than of salt revenues). Aside from major foreign

loans and domestic bond issues, there were treasury notes (short- and

long-term), bank advances, obligations contracted

by

specific ministries,

salaries in arrears and other debts, •whose total has never been calculated.

Although money became increasingly difficult to raise,

it

is doubtful that

a fraction

of

what the government borrowed domestically would have

been available without the constant

(if

usually disappointed) expectation

of large foreign loans and the security provided for some domestic bond

issues by customs and salt revenues.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE PEKING GOVERNMENT 267

The borrowed money went into politics ('honorariums' to members of

parliament and journalists) and the armies of militarists allied with

Peking's rulers. Meanwhile, government offices were starved for funds.

Salaries went unpaid and teachers, police and bureaucrats went on strike,

demonstrated, and took bribes and second jobs to survive. Under the

circumstances it is remarkable that any useful administrative work was

performed. Yet there are indications that several ministries functioned

fairly effectively throughout much of the period.

Elementary, secondary and higher educational institutions raised

standards and expanded enrolments under the Ministry of Education's

centralized leadership.

1

' The court system under the Ministry of Justice

remained incomplete and under-used but enjoyed a reputation for honesty,

and there was progress in law codification and prison administration.

Under the Ministry of Interior, Peking's modern police force kept its

professional standards so high that Peking was described in 1928 as 'one

of

the

best-policed cities in the world.'

14

The railways, telegraph and postal

services of the Ministry of Communications functioned profitably and

quite reliably despite occasional warlord attempts at interference. These

surface impressions need to be followed up with careful research on the

bureaucracy to see how the marriage of the indigenous tradition of

bureaucratic service with Western technical and professional norms

survived in such hostile political surroundings.

Perhaps the most effective of Peking's ministries - yet the most often

attacked by contemporaries and posterity - was foreign affairs. Its cosmo-

politan diplomats - men like V. K. Wellington Koo and W. W. Yen -

doggedly pursued the task of rights recovery on behalf of a nation that

lacked the military or financial capability to defend

itself.

By declaring war

on Germany and Austria-Hungary in 1917, China cancelled their extra-

territorial rights and terminated their Boxer indemnity payments, also

winning a five-year suspension of Boxer payments to the Allies. Although

purely nominal, China's entry into the war gave her the prestige of par-

ticipating as a victor in the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. The Treaty of

Versailles severely disappointed the Chinese by passing German rights

in Shantung to Japan, but China's diplomats had gained points in the

court of international opinion; in the Washington Conference of 1921-2

Japan was forced to agree to withdraw from Shantung. In addition,

Great Britain agreed to return Weihaiwei; the nine powers declared they

13 H. G. W. Woodhead, ed. The China year

book

1926-7, 407-10. For Justice, see 753-68; for

Communications, 269-385.

14 New York Times, 30 Dec. 1928, quoted in David Strand, 'Peking in the 1920s: political

order and popular protest' (Columbia University, Ph.D. dissertation, 1979), 43-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

268 THE PEKING GOVERNMENT, I 9 I 6-2 8

would respect China's sovereignty;

the

customs tariff

was

raised

to 5

per cent;

and

provisions were made

for

eventual tariff autonomy

and

abolition

of

extraterritoriality. China gained further

in the 1924

Sino-

Soviet treaty: Russia gave up extraterritoriality, its concessions

at

Tientsin

and Hankow, and Boxer indemnity payments.

In

1926, even as the Peking

government was

on

the brink

of

collapse, the Foreign Ministry persuaded

the powers

to

send delegates

to a

Tariff Revision Conference.

The con-

ference disbanded inconclusively but the elaborate Chinese position papers

formed

the

basis

for the

Nanking government's successful claim

of

tariff

autonomy

in

1928.

The

arduous negotiations behind

all

these achieve-

ments have

yet to be

studied, except

for

those leading

to the

1924 Sino-

Soviet treaty:

the

scholar

of

this event concludes that

the

Ministry

of

Foreign Affairs

'had

more power

and

independence, more continuity,

better personnel, more positive policies

and

nationalistic motivations

than most people realize.'

1

'

THE POLITICAL ROLE OF THE MODERN BANKS

An increasingly important feature

of

Peking politics

in

the early republic

and into

the

1920s

was the

political involvement

of

the modern treaty-

port Chinese banks. Within

the

world

of

Chinese banking, these banks

were flanked

on

one side by the treaty-port branches

of

the foreign banks,

and

on the

other

by the

ch'ien-chuang

(traditional money shops); both

types

of

institutions were financially stronger than

the

Chinese modern

banks.

The 27

foreign banks with branches

in

China commanded three

or four times

the

capital

of the 119 (or

more) Chinese banks. They

virtually monopolized

the

lucrative foreign exchange

and

foreign trade

markets,

and

enjoyed the privileges

of

issuing currency

and of

receiving

several hundred million dollars

per

year

in

salt

and

customs receipts.

They

had the

trust

of

Chinese

and

foreign businessmen alike

and did

the bulk

of the

banking business

in the

treaty ports.

The

innumerable

money shops,

on the

other hand, were strongly entrenched

in the

fields

of domestic currency exchange, securities speculation

and

short-term

loans.

While individually small, they

had

capital totalling more than

that

of

the modern banks, and because they enjoyed established channels

of activity they were more successful

in

maintaining liquidity than

the

modern banks. Indeed, the money shops served

as a

source

of

short-term

capital

for the

modern banks.

The modern banks were financially weak

in the

early republic. With

15 Sow-theng Leong,

Sino-Soviet diplomatic

relations,

1917-1926, 294-95.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE POLITICAL ROLE OF THE MODERN BANKS 269

an aggregate authorized capital of

Ch.$3 50

million, the 119 modern banks

on which data are available were able to raise only Ch.$i5o million in

paid-up capital.

16

Because of low public confidence, they had to attract

working funds, of which they were desperately short, by issuing paper

money (if government authorization could be obtained), borrowing from

the money shops at high interest, and accepting savings deposits at high

interest. Then, in order to pay back the high-interest loans and deposits

and support the value of their notes, the banks were forced to seek highly

profitable, and therefore speculative, investments. Government bonds

and treasury notes were an important part of such investment.

The government was driven increasingly into the domestic capital

market as its other sources of revenue dried up. Domestic tax revenues

started a precipitous decline in late 1915 when a number of provinces

declared their independence of Peking in response to Yuan Shih-k'ai's

imperial movement. In 1918 the new Hara Kei cabinet in Japan abandoned

its predecessor's policy of granting generous, poorly-secured loans to

China. A consortium of foreign bankers, organized in 1920, became the

instrument of what was in effect a prolonged foreign financial boycott of

the Chinese government (see chapter 2). As a result of these developments

domestic credit became increasingly crucial to the revenue-raising activi-

ties of a series of desperate ministers of finance. Beginning with the

Eighth-Year Bonds in 1919, however, bankers' enthusiasm for govern-

ment securities waned. The government was deeply in debt, there was

no reliable revenue left on which to secure the new bonds, and the polit-

ical situation was insecure. Bankers were able to exact harsh terms from

the government for small advances of cash. Left-over First-Year Bonds

were sold by the government in Shanghai for Ch.S21.50 per $100 face-

value; unsold Seventh-Year Bonds were sold for Ch.$54 per 8100 bond.

Banks made numerous short-term loans to the government at 16 to 25

per cent interest per month, with unsold bonds, valued at 20 per cent of

face-value, used as security. From 1912 to 1924, 01.546,740,062 worth

of treasury bills, payable in one or two years, were sold to banks at as

little as 40 per cent of face-value, providing a handsome rate of return

upon redemption.

The modern banks thus became the major holders of government

bonds. The bonds could be bought at a fraction of face-value and often

with the bank's own notes, but they might never be repaid and their

value might continue to fall. On the other hand, the market value might

leap at the news that a new security had been found for the issue, or that

16 For documentation see Nathan, Peking

politics,

74-90.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

270 THE PEKING GOVERNMENT, I 9 I 6-2 8

a drawing would be held to redeem a portion of it, or that a new minister

of finance was to be appointed. Bonds could prove a profitable investment

because their market value rose and fell so violently.

To

speculate with

success, however,

it

was necessary

to

anticipate

or

even influence

the

movements

of

the market. This required close political contacts.

The modern banks with headquarters

in

Peking

and

Tientsin were

most closely involved in Peking politics. (The Shanghai banks also spec-

ulated

in

government bonds but did much

of

their business

in

exchange

transactions

and

industrial investments; other treaty-port banks were

more closely involved in local politics than in Peking politics.) The typical

board

of

directors

of

a Peking or Tientsin bank was carefully composed.

At its heart were

a

number

of

professional bankers with good contacts

with

a

variety of political factions. To these were added men of banking

or other financial experience who were more closely identified with one

political group or another. The purpose

of

such balancing was to provide

banks with intelligence on the political facts that determined fluctuations

in the market price of bonds and with friends in government who could

obtain and protect privileges,

but to

avoid

a

political one-sidedness

in

the bank's allegiances that might leave

it

defenceless when the political

situation changed.

As the government became more and more impecunious after 1919,

the political power

of

banks, and

of

political factions with influence

in

banking circles, increased. The Communications Clique (described below)

emerged as an especially powerful arbiter

of

the fate

of

cabinets.

At

the

same time, the ability

of

banks

in

general

to

enforce their interests

on

the government was strengthened. Meeting

in

Shanghai

in

December

1920,

the

Chinese Bankers' Association decided

to

refuse

to

buy any

more government bonds until the government 'readjusted' the means of

paying off the old ones. In response, by presidential mandate

of

3

March

1921,

the government committed

its

customs surplus

to a

sinking fund

called

the

Consolidated Internal Loan Service, administered

by the

inspector-general

of

customs,

Sir

Francis Aglen.

The

First-, Fifth-,

Seventh-Year Long-Term, Eighth-, and Ninth-Year Bonds (other issues

were later added) were revalued at a portion of face-value and exchanged

for two new bond issues,

the

service

of

which was guaranteed

by the

fund.

The establishment

of

the Consolidated Internal Loan Service was

a

boon to the bankers. The bonds had been revalued below face-value, but

this did not matter because the banks had originally purchased them

at

large discounts. Now,

by

waiting

for the

loan service

to

redeem

the

bonds, the banks could receive twice what they had paid

for

them;

or,

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FACTIONALISM AND PERSONAL CONNECTIONS 27I

if they wished

to

trade the bonds, they could sell them

at a

higher price

than they had paid. The government's credit was also enhanced, although

the blessing

of

Sir Francis Aglen now became necessary

for

the success

of any new government-bond issue.

FACTIONALISM AND PERSONAL CONNECTIONS

The institutional facade

of

the Peking government was constitutional:

legislative, executive and judicial functions parcelled out

by

law, policy

decisions made

by

institutional procedures.

The

reality was factional:

personal followings, cutting across the boundaries of official institutions,

each faction centred

on a

particular leader and composed

of

his indivi-

dually recruited, personally loyal followers.

In building such factions, political leaders kept alert

for

promising

men who were able, politically active and trustworthy. The judgment of

trustworthiness

was

heavily influenced

by the

idea

of

'connections'

(Jkuan-hsi).

To

most Chinese, society consisted

of a

web

of

defined role

relationships such as father-son, ruler-minister, husband-wife and teacher-

student.

It

was much safer

to

trust those with whom one had some de-

finite connection than those who were merely acquaintances. Even

if

the connection was remote,

it

helped introduce stability into

a

relation-

ship:

it

identified the senior and the junior member, and involved reliable

rules about what one member had the right to ask or expect of the other.

Connections among blood relatives

or

in-laws,

of

course, were highly

important, although where

the

relative

in

question was

not

politically

skilful, he would be given a sinecure rather than a sensitive post. Another

important kind of connection was between persons hailing from the same

locality

or

region

of

China. Given the linguistic and cultural diversity of

the nation, Cantonese

or

Anhweinese far from home in Peking tended

to

stick together. Other foci of loyalty grew out of the educational process:

those who had studied together under the same teacher, graduated from

the same school,

or

passed the pre-1905 civil service examinations

in

the

same year considered one another fellow-students,

a

relationship which

was often closer

and

more intimate than that between brothers. Such

fellow-students also owed solemn

and

lifelong loyalty

to

their former

teachers and examination supervisors. Similarly, ties to former colleagues

and superiors grew out of bureaucratic service. In addition to, or instead

of, such automatically-formed connections, one man might link himself

to another in a master-disciple relationship, a patron-protege relationship,

or in sworn brotherhood.

On the basis of extensive networks of connections, outstanding politi-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

272 THE PEKING GOVERNMENT, I 9 I 6-2 8

cal leaders gathered around themselves factions of

able,

well-placed, loyal

followers. In the unfamiliar institutional world mandated by the repu-

blican constitutions, the leaders relied more and more on their factions to

carry on political action.

One of the most influential and complex factions was headed by Tuan

Ch'i-jui (1865-1936). Tuan graduated from the artillery course at the

Peiyang Military Academy in 1887, and, after further study in Germany,

he became commander of the artillery corps and supervisor and chief

lecturer at the artillery school at Hsiao-chan, where Yuan Shih-k'ai was

training his Newly Created Army (see volume

11,

chapter 10). Because of

his important role at Hsiao-chan, about half of the officers of the Newly

Created Army, including many of the important North China militarists

of the early republic, were his students. Tuan had access to another large

pool of political talent as a native of Hofei, Anhwei, a city whose sons

displayed strong localistic identification and uncommon political skill.

Although he was an army general, Tuan did not have a warlord-style

political base in the direct command of troops or the control of territory.

His influence was based upon seniority, prestige and skill, and particularly

upon his large personal following.

Through his followers Tuan's influence during the republican years

was felt in many sectors of the government - the War Participation (later

Border Defence) Army; the ministries of interior, finance, communica-

tions and others; the cabinet secretariat; the Peking-Hankow railway;

the government-owned Lungyen Iron Mining Company; the Supreme

Court. Of particular interest for this essay was the way in which Tuan

projected his power into the parliament of 1918-20 through a parliamen-

tary association called the Anfu Club, organized by two of his close as-

sociates, Wang I-t'ang and Hsu Shu-cheng. Wang was a native of Tuan's

home city, Hofei, and a protege of Tuan's. Hsu was a young army officer

whom Tuan had selected during the late Ch'ing as an aide. (The Anfu

Club is described below.)

Another leading republican faction was the Communications Clique.

Its origins lay in the late Ch'ing Ministry of Posts and Communications

(Yu-ch'uan pu, founded in

1906).

As resources were poured into it for con-

structing or redeeming railways, extending the telegraph system, and

founding the Bank of Communications, the ministry became an important

locus of political and financial power. Followers of Yuan Shih-k'ai staffed

the ministry and its agencies. One of them was Liang Shih-i (1869-1933),

who from 1906 to 1911 held perhaps the most important post in the mini-

stry, that of director-general of the Railway Bureau. According to a later

description by American Minister Paul Reinsch, Liang 'was credited as

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008