The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

MAPS

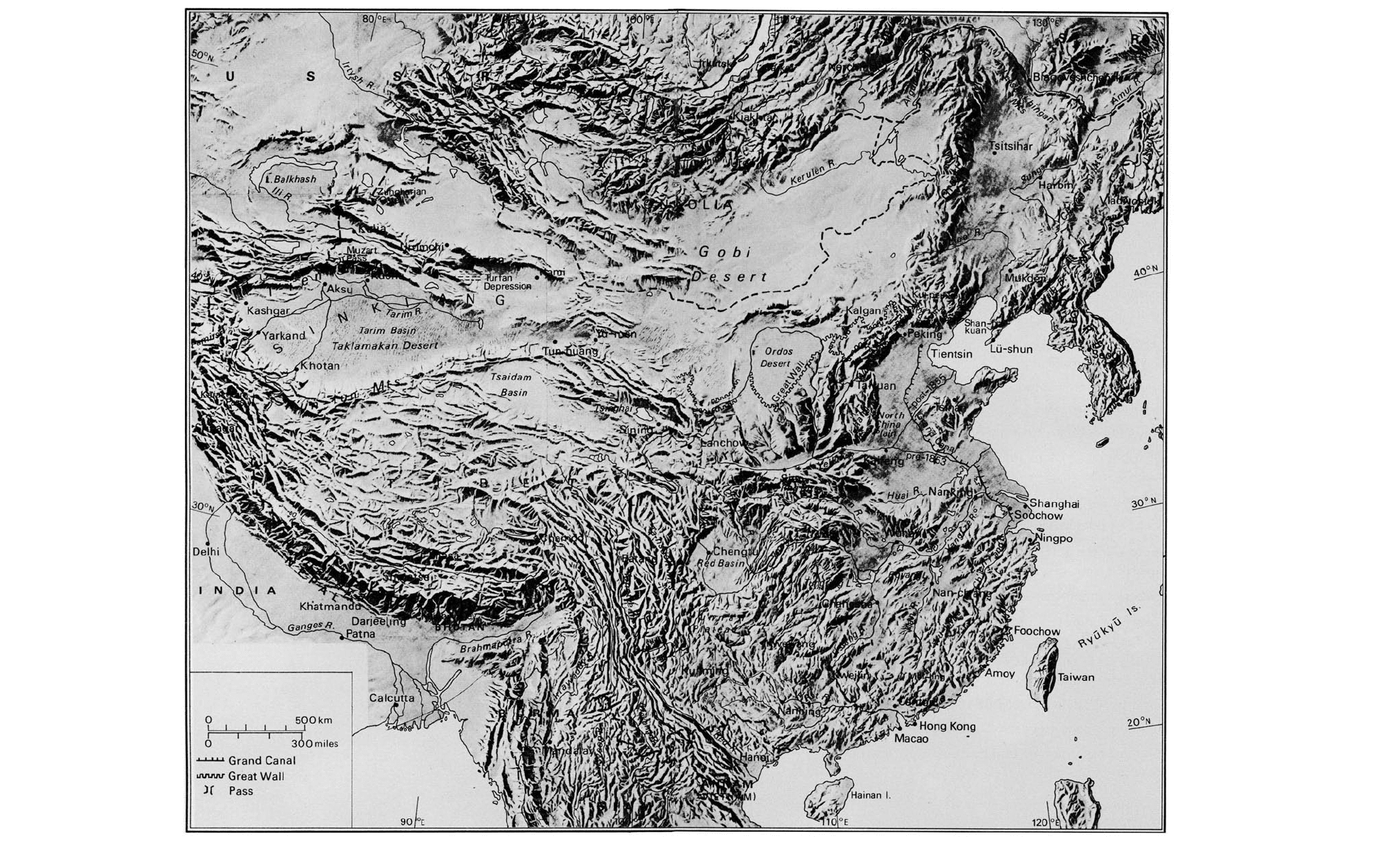

1 Republican China - physical features xii

2 Provinces of China under the Republic 30

3 Major crop areas 65

4 Railways as of 1949 92

5 Foreign 'territory' in China about 1920 130

6 Treaty ports - Shanghai ca. 1915 134

7 Treaty ports - Tientsin ca. 1915 138

8 Wuhan cities ca. 1915 140

9 Distribution of warlord cliques in 1920 298

10 Distribution of warlord cliques in 1922 299

11 Distribution of warlord cliques in 1924 300

12 Distribution of warlord cliques in 1926 301

13 Kwangtung and Kwangsi in the early 1920s

5

54

14 The Northern Expedition 1926-28 580

15 Hunan and Kiangsi during the Northern Expedition 582

16 Hupei 584

17 The Lower Yangtze region 615

18 North China about 1928 703

XI

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

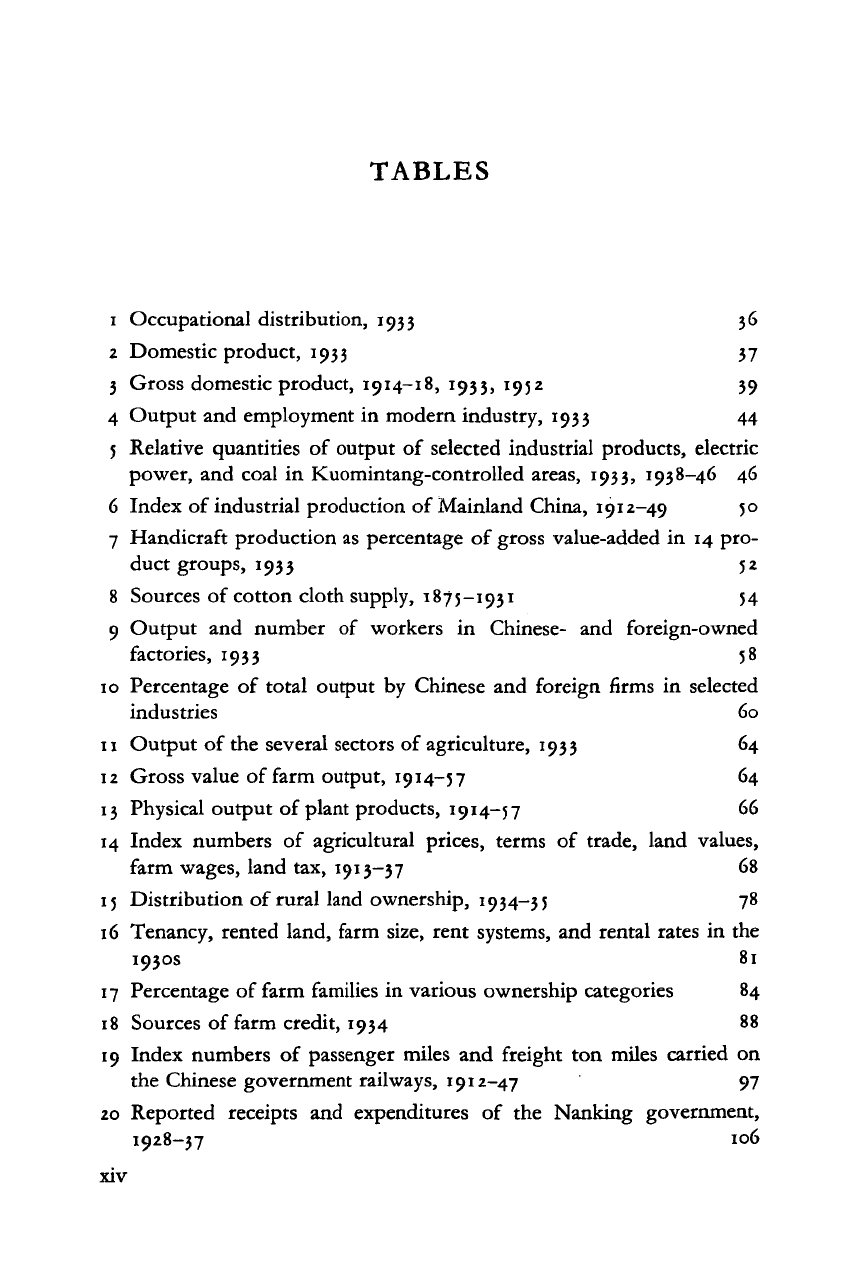

TABLES

1 Occupational distribution, 1933 36

2 Domestic product, 1933 37

3 Gross domestic product, 1914-18, 1933, 1952 39

4 Output and employment in modern industry, 1933 44

5 Relative quantities of output of selected industrial products, electric

power, and coal in Kuomintang-controlled areas, 1933, 1938-46 46

6 Index of industrial production of Mainland China, 1912-49 50

7 Handicraft production as percentage of gross value-added in 14 pro-

duct groups, 1933 52

8 Sources of cotton cloth supply, 1875-1931 54

9 Output and number of workers in Chinese- and foreign-owned

factories, 1933 58

10 Percentage of total output by Chinese and foreign firms in selected

industries 60

11 Output of the several sectors of agriculture, 1933 64

12 Gross value of farm output, 1914-57 64

13 Physical output of plant products, 1914-57 66

14 Index numbers of agricultural prices, terms of trade, land values,

farm wages, land tax, 1913-37 68

15 Distribution of rural land ownership, 1934-35 78

16 Tenancy, rented land, farm size, rent systems, and rental rates in the

1930s 81

17 Percentage of farm families in various ownership categories 84

18 Sources of farm credit, 1934 88

19 Index numbers of passenger miles and freight ton miles carried on

the Chinese government railways, 1912-47 97

20 Reported receipts and expenditures of the Nanking government,

1928-37 106

xiv

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

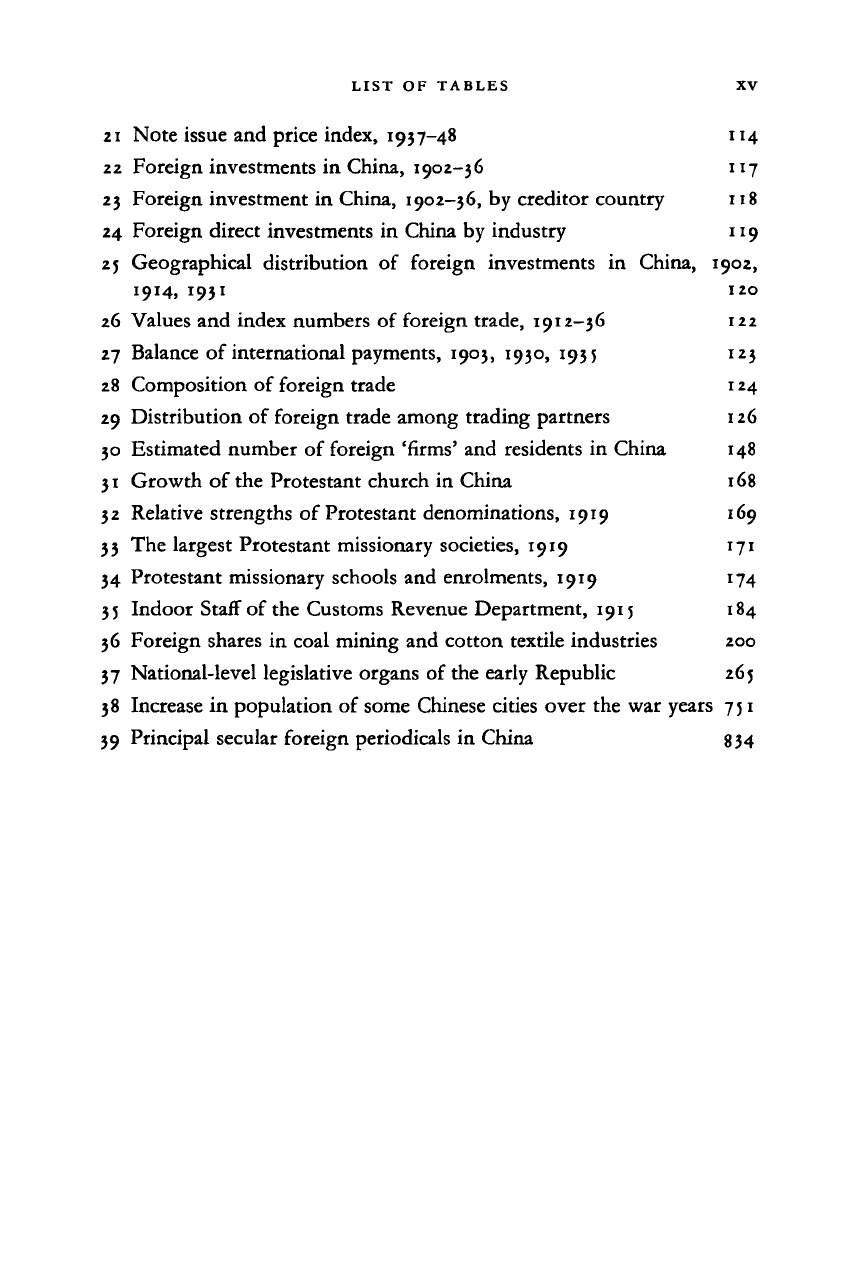

LIST OF TABLES XV

21 Note issue and price index, 1937-48 114

22 Foreign investments in China, 1902-36 117

23 Foreign investment in China, 1902-36, by creditor country 118

24 Foreign direct investments in China by industry 119

25 Geographical distribution of foreign investments in China, 1902,

1914, 1931 120

26 Values and index numbers of foreign trade, 1912-36 122

27 Balance of international payments, 1903, 1930, 1935 123

28 Composition of foreign trade 124

29 Distribution of foreign trade among trading partners 126

30 Estimated number of foreign 'firms' and residents in China 148

31 Growth of the Protestant church in China 168

32 Relative strengths of Protestant denominations, 1919 169

33 The largest Protestant missionary societies, 1919 171

34 Protestant missionary schools and enrolments, 1919 174

35 Indoor Staff of the Customs Revenue Department, 1915 184

36 Foreign shares in coal mining and cotton textile industries 200

37 National-level legislative organs of the early Republic 265

38 Increase in population of some Chinese cities over the war years 751

39 Principal secular foreign periodicals in China 834

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE TO VOLUME 12

On romanization

One achievement of the revolution has been to set up an official system for

transcription of Chinese sounds into alphabetic writing. This system,

known as

pinyin,

one hopes may bring uniformity into a formerly chaotic

situation, in which the sinologists of each foreign power had devised

their own national systems of romanization - English, French, German,

Russian, etc.

In the English-reading world the Wade-Giles romanization after the

turn of the century gradually became accepted for scholarly work, despite

its idiosyncrasies - for instance, its use of an apostrophe as an aspiration

mark to distinguish, for example, T (written in Wade-Giles T') from D

(Wade-Giles T), P (P') from B (P), K from G, etc. Despite this clumsy

feature, Wade-Giles became by 1949 the most widely used system,

enshrined in countless reference works, official documents, and the general

literature of the field. For example, the four major biographical diction-

aries in English of Chinese personages from 1368 to 1965 (totalling eleven

volumes) all use Wade-Giles. Moreover, because of the foreign presence

in China, the historical record is partly non-Chinese. It is for this reason -

that Wade-Giles is still the dominant system in some of the sources and in

the research tools of the period covered in this volume - that we continue

to use it here. The use of the new

pinyin

system in this volume would

greatly complicate the work of researchers.

Acknowledgements

The editor is most indebted to the authors for their unremitting patience

and cooperation, so necessary for this sort of enterprise; to Katherine

Frost Bruner for indexing and to Joan Hill for administrative and edi-

torial assistance; to Chiang Yung-chen of the Harvard Graduate School

for essential bibliographical assistance and to Winston Hsieh, the Univer-

sity of Missouri, and Guy Alitto, the University of Chicago, for biblio-

graphic consultation. We are indebted for support of editorial costs to the

Ford Foundation and to the National Endowment for the Humanities

xvii

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

XV111

through the American Council of Learned Societies. A working con-

ference of contributors was held in Cambridge, Mass, in August 1976 with

the assistance of the Social Science Research Council. During the gesta-

tion period earlier versions of chapters 2, 3 and 12 were published as

separate booklets. Now they are born again.

JKF

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER

1

MARITIME AND CONTINENTAL IN

CHINA'S HISTORY

The 37 years from 1912 to 1949 are known as the period of the Chinese

Republic in order to distinguish them from the periods of more stable

central government which came before and after. These years were

marked by civil war, revolution and invasion at the military-political

level, and by change and growth in the economic, social, intellectual and

cultural spheres. If we could neatly set forth in this first chapter the

major historical issues, events and Chinese achievements in these various

realms, the following chapters might be almost unnecessary. In that

case,

however, the cart would be in front of the horses.

Our new view of the republic must come from several angles of ap-

proach. Only one is pursued in this introductory chapter, yet it appears

to serve as a central and necessary starting point.

THE PROBLEM OF FOREIGN INFLUENCE

China's modern problem of adjustment has been that of a dominant,

majority civilization that rather suddenly found itself in a minority

position in the world. Acceptance of outside 'modern' ways was made

difficult by the massive persistence of deeply-rooted Chinese ways. The

issue of outer versus inner absorbed major attention at the time and still

confronts historians as a thorny problem of definition and analysis.

Anyone comparing the Chinese Republic of 1912-49 with the late

Ch'ing period that preceded it or with the People's Republic that followed

will be struck by the degree of foreign influence upon and even participa-

tion in Chinese life during these years. The Boxer peace settlement of 1901

had marked the end of blind resistance to foreign privilege under the

unequal treaties; students flocked to Tokyo, Peking proclaimed foreign-

style reforms, and both weakened the old order. After the Revolution of

1911 the outside world's influence on the early republic is almost too

obvious to catalogue: the revolutionaries avoided prolonged civil war

lest it invite foreign intervention; they tried in 1912 to inaugurate a

constitutional, parliamentary republic based on foreign models; President

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2 INTRODUCTION: MARITIME AND CONTINENTAL

Yuan Shih-k'ai's foreign loans raised controversy; the New Culture move-

ment after 1917 was led by scholars returned from abroad; the May

Fourth movement of 1919 was triggered by power politics at Versailles;

the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was founded in 1921 under Comin-

tern prompting; Sun Yat-sen reorganized the Kuomintang (KMT) after

1923 with Soviet help; the Nationalist Revolution 1925-27 was inspired

by patriotic anti-imperialism. Truly, the early republic was moved by

foreign influences that were almost as pervasive as the Japanese invasion

was to become after 1931.

Yet the term 'foreign' is highly ambiguous and may trap us in needless

argument. It requires careful definition. For example, among the 'foreign

influences' just listed, some were events abroad, some were models seen

abroad and imitated in China, some were ideas of foreign origin which

animated Chinese returned from overseas, some were events in China in

which foreign people or ideas played a part. The situation was not simple.

Since the 'foreign' elements in Chinese life during this period were so

widespread, clarity demands that we make a series of distinctions or

propositions. First of all, most readers of these pages probably still

perceive China as a distinct culture, persistent in its own ways, different

from 'the West'. This assumption, reinforced by common observation,

stems from the holistic image of 'China' conveyed by Jesuit writers during

the Enlightenment and further developed by European Sinology. It

represents an acceptance in the West of an image of China as an integrated

society and culture, an image that formed the central myth of the state

and was sedulously propagated by its learned ruling class.

1

Still dominant

in Chinese thinking at the turn of the century, this idea of 'China' as a

distinct cultural entity made 'foreign' into something more than the mere

political distinction that it sometimes was among Western nations.

Second, we must distinguish the actual foreign presence. There were

many foreigners within the country - scores of thousands residing in the

major cities, most of which were treaty ports partially foreign-run;

hundreds were employed by successive Chinese governments; and several

thousand missionaries were at stations in the interior. Add to these the

garrisons of foreign troops and foreign naval vessels on China's inland

waterways, and we can better imagine the 'semi-colonial' aspect of China

under the unequal treaties that continued to give the foreigners their

1 On Sinology and the 'self-image of Chinese civilization', see Arthur F. Wright, 'The study

of Chinese civilization',

Journal

of the History of

Ideas,

21.2 (April-June i960) 233-55. In

developing this essay I have greatly benefited from comments of Marie Claire Bergere,

Mark Elvin, Albert Feuerwerker, Kwang-Ching Liu, Philip A. Kuhn, Denis Twitchett and

Wang Gungwu.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008