The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 12: Republican China, 1912-1949, Part 1

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE TREATY-PORT MIXTURE 23

tans.

44

Presumably there was a comparable drive among Chinese merchants

in their search for success.

Either this drive for success or their speculative impulse, for which

they are famous, made Chinese merchants the chief actors in the treaty-

port trade. The early comprador-managers of the new Western trade came

from the mixed pidgin-English milieu of Canton-Macao. But the growth

of Shanghai was led by Chekiang merchant-bankers from Ningpo, the

southern anchor of the coast trade to Manchuria. Very soon after China's

final opening in 1860 the big firms like Jardine, Matheson and Company

found it needless to staff the smaller ports with the usual young Scotsmen

because their Cantonese or Ningpo compradors could handle the trade

just as well alone.

The growth of treaty-port trade in China brought with it the new

technology of transport and industry, a new knowledge of foreign nations,

and so a growth of nationalism. The pioneer geographies of missionaries

like Gutzlaff and Bridgman stimulated the production of the early geo-

graphies of Wei Yuan and Hsu Chi-yii, which in the 1840s anticipated

the translation programmes of the Kiangnan Arsenal and the Society

for the Diffusion of Christian and General Knowledge (SDK) in later

decades. Christian reformers and journalists like Wang T'ao arose under

foreign influence in Hong Kong and the treaty ports to urge the cause of

Chinese nationalism. Sun Yat-sen came from near the earliest foreign port,

Macao, and was educated abroad in Honolulu and Hong Kong. That

most of his active life was lived outside China, although he was the chief

apostle of its modern nationalism, illustrates how China's Westernizers

generally were men of the coastal frontier.

The new ideas conveyed by such forerunners were neither all-foreign

nor all-Chinese in origin. Wei and Hsu showed proper statecraftsmen's

interest in Western technology. Wang and Sun were concerned about

popular participation in government. The twentieth-century Chinese

reformers' slogan 'Science and Democracy' had its nineteenth-century

antecedents both in China and abroad.

China's maritime connections thus not only served as the channels

of the Western invasion, they also drew a new Chinese leadership into

the new port cities like Shanghai, Tientsin, Kiukiang and Hankow. As

more and more students went to Japan and the West to study how to save

their homeland, they were drawn away from the rural scene with which

44 In finding a Confucian ethic similar to the Protestant ethic, Thomas A. Metzger even sug-

gests 'China's transformative vision of modernization was itself rooted in tradition' - a

lively topic. See 'Review symposium' on Thomas A. Metzger's

Escape

from

predicament:

Neo-Confucianism

and

China's evolving

political

culture,

in JAS, 39.2 (Feb. 1980) 235-90. See

282.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

24 INTRODUCTION: MARITIME AND CONTINENTAL

China's gentry ruling class had ordinarily retained contact. China's new

modernizers generally lost their agricultural roots. In the end many were

deracinated. The young revolutionaries of the Kuomintang generation

from 1895 onwards were typically urban products less acquainted with

the peasant villages. In their effort to save China by Westernization

they mastered many aspects of Western learning and technology but

often found themselves out of touch with the Chinese common people.

But their demands for constitutional government, for railway building

under Chinese control, for the recovery of sovereign rights impaired by

the unequal treaties, all contributed to the extinction both of the Manchu

dynasty and of the monarchy of the Son of Heaven. All these nationalistic

demands showed foreign influence.

The first phase of the Chinese revolution in this way represented both

Chinese and foreign influences conveyed largely through the medium

of Maritime China. The treaty ports reinforced and gave scope to the

Chinese tradition of overseas trade free of bureaucratic control abroad.

This minor tradition of maritime enterprise and economic growth, most

evident to foreigners originally at Singapore and Canton and also in the

opium and coolie trades, contributed to the hybrid society of the treaty

ports and nurtured the Westernization movement as well as the early

Chinese Christian church. It fostered individualism and an interest in

scientific technology at the same time that it aroused patriotism and pride

of culture.

We cannot yet describe in detail the 'maritime' impact on Chinese

business organization and practice. But certain broad effects are already

apparent. Because the Chinese patriots who sprang from this background

were seldom rooted in the villages, their new nationalism concentrated

its hopes upon the Chinese state-and-culture as a whole, 'China' as against

the outside nations. The mechanical devices of industry and the political

institutions of constitutional democracy both seemed at first to be essen-

tial importations for the salvation of 'China'. This first generation after

1900 had little concept of or desire for basic social revolution. Sufficient

unto the day was the problem of creating a unified Chinese nation-state

and its necessary economic base.

For this purpose of national salvation China's central tradition of

course had much to offer. The aim of nation-building could be subsumed

under the ancient Legalist slogan 'enrich the state, strengthen the military'

(fu-kuo

ch'iang-ping),

as had been done in Japan. Projects for this purpose

appeared as new applications of the Ming and Ch'ing administrators'

art of statecraft, which extolled learning 'of practical use in the adminis-

tration of society'

(ching-shih

chihyung).

In practice this often involved in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE TREATY-PORT MIXTURE 25

time-honoured fashion the management and manipulation of the populace.

Popular training under firm safeguards was foreseen as a necessary

prerequisite for modern self-government. By some this was given the

name 'tutelage'. Thus China's bureaucratic tradition seemed to offer

help in the pursuit of the Western goal of popular participation.

Emerging from this background, the Revolution of 1911 shares the

ambivalence of the treaty-port era as a whole. In form it is more an end

than a beginning. To some degree it is the petering out of a dynasty,

although to some degree it is a triumph of nationalism and other influences

coming by sea to the port cities of China's littoral along the coast and up

the Yangtze. Revolutionary organizing is chiefly by returned students

from Japan. Financing comes from Overseas Chinese communities.

Ideas like constitutionalism and the Three People's Principles of Dr

Sun come from the liberal West. Yet those who attain power in the pro-

vincial assemblies of 1911 are not the revolutionaries but the new mer-

chant gentry, while military men become governors. They all believe in

the economic and military development visible in Japan and the industri-

alizing Western nations, but violent revolution is not what they desire.

The business class that emerges is similarly ambivalent. Modern-

style Chinese banks become active auxiliaries of government finance,

buying bond issues at large discounts and creating a new class of financiers

who hover on the borderline between simple, bureaucratic capitalism and

actual industrial enterprise. For a time in the 1920s, as our chapter 12

below indicates, the ideology of liberalism is as widely embraced among

Shanghai merchants as among Peking intellectuals.

From the 1890s we may discern several features of modern Chinese

life associated with or coloured by the maritime tradition: first, the pro-

priety and prestige of things foreign, including Christianity, then the

spreading sense of nationalism and of the struggle for survival among

nations. With this came ideas of progress and the vital role of science and

technology, concepts of individualism less bound by family ties and,

more vaguely, of political rights and constitutional government. Finally,

underlying all of these was the independent respectability of capitalist

enterprise and its need for legal safeguards.

The mere recital of such themes, which figure, prominently in this

volume, suggests the limitations of Maritime China vis-a-vis the problems

of the great heartland. Deep within China the issue was not simply to

develop and apply more broadly an urban way of life and institutions of

trade that had long been nurtured in China's old society and its foreign

contact. On the contrary, the issue among the peasant villages was one of

continuity versus disruption, how to remake the traditional order to take

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

26 INTRODUCTION: MARITIME AND CONTINENTAL

account

of

modern technology, modern egalitarianism

and

political

participation. This

was an

issue,

as we now see, of

social transformation

and regeneration;

in the end, of

revolution.

But social revolution

was not

espoused

in

1911.

One

reason

was

still

the ingrained political passivity

of the

peasant masses

and

their lack

of

leadership. Another reason

was the

patriotic fear that prolonged disorder

would invite foreign intervention. Revolutionaries

of

all camps therefore

'accepted

the

compromise that stopped

the

revolution short

and

brought

Yuan Shih-k'ai

to

power.

The

determining factor

was the

foreign omni-

presence.'

4

'

Yet, being foreign,

the

foreign omnipresence remained superficial

to

the

vast mass

of

agrarian China.

The

traditional rural society kept

on

its

way in its own

style,

not yet

disrupted

by

urban-inspired changes.

The

new

leaders

of

Chinese nationalism

in the

1920s were

not

produced

directly from

it nor

concerned primarily with

its

problems. Peasant China,

in short, proved

to be a

further bourne, beyond

the

purview

and

capacity

of urban-centred

and

foreign-inspired revolutionaries.

We

leave

it

beyond

the scope

of

this introductory essay.

China's social revolution

was a

long time coming.

It

could

not

easily

find a foreign model. Insofar

as

China's peasant mass

was

uniquely large,

dense

and

imperturbable,

the

ingredients

of

social revolution

had to be

mobilized mainly from within

the old

society. This could

not be

done

quickly

but

only

in

proportion

as the

immemorial agrarian society

was

infiltrated

by

urban-maritime ideas (like that

of

material progress),

subjected

to

greater commercialism, upset

by new

values (like women's

equality)

and

shattered

by

warfare, rapine

and

destruction.

So

much

had

to

be

torn down

and

shown

up! Yet

even then

the

agrarian society could

never

be a

clean slate awaiting fresh writing.

The new

message

had to

use

old

terms

in

a fresh way and create its new order

out

of old ingredients.

Insofar

as

Maritime China

was a

channel

for

change,

it

started some-

thing

it

could

not

finish. The rebel tradition in the old agrarian-bureaucratic

China

had

been that

of

millenarian sects like

the

White Lotus Society

in

the north

and of

brotherhoods among places

of

trade like

the

Triad

Society

in the

south. This rebel tradition

had

been secret

and

fanatical,

too often

in the

negative guise

of

Boxerism, profoundly anti-intellectual

and likely

to

degenerate into local feuding.

46

What happens

in the

twen-

tieth century

to

revolutionize

the

major agrarian-bureaucratic tradition

45

Mary Clabaugh Wright, China in

revolution:

the

first phase

1900-191),

55.

46

For a

recent close look

at

Boxer phenomena see Mark Elvin, 'Mandarins and millennarians:

reflections

on the

Boxer uprising

of

1899-1900', journal

of

the

Anthropological

Society

of

Oxford,

10.3

(1979)

115-38.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE TREATY-PORT MIXTURE Zf

of the Chinese heartland is thus another universe of discourse and research.

It is even more complex and multi-faceted than China's minor maritime

tradition that we have just been sketching. We are just beginning to un-

derstand its structures of folk religion, familism and local economy.

In the present volume the next two chapters, on the Chinese economy

and the foreign presence, provide a framework for both volume 12 and

volume 13 by covering their subjects down into the late 1940s. The

following three chapters deal with President Yuan Shih-k'ai, the Peking

government and the warlords - mainly North China politics

—

to 1928.

Chapters 7, 8 and 9 then pursue developments in thought and in literature

from the 1890s to 1928, while chapters 10 and 11 concern the early com-

munist movement and the complex course of the Nationalist Revolution

in the tumultuous mid 1920s. The volume concludes with the checkered

career of the business class, mainly in Shanghai, into the 1930s.

Volume 13, in addition to the history of the Nationalist government,

the Japanese invasion, and the rise of the CCP, will consider certain aspects

of the early republic not dealt with here. These include the transformation

of the local order (whatever happened to the gentry class

?),

the nature of

the peasant movement, the growth of the modern scientific-academic

community, the vicissitudes of China's foreign relations centring around

the aggression of Japan, and the great Sino-Japanese and KMT-CCP

conflicts between 1937 and 1949. Even this further range of subject matter

may leave us hard put to trace the revolutionary processes at work in the

remnants of China's ancient rural society. Perhaps we can understand how

even the communist movement in China, though posited on a faith in

social revolution, found the secret of success only after 1928. In the con-

text outlined above, Mao Tse-tung's task thereafter was how to supplant

or 'modernize' China's continental tradition, the agrarian-bureaucratic

and local-commercial order of the heartland. In the effort he confronted

the heritage of Maritime China, the industrial technology and foreign

trade of port cities, though they no longer seemed a minor tradition.

Plainly, abstractions such as Maritime and Continental China have

fuzzy edges - they are suggestive rhetoric rather than analytic cutting

tools.

Yet they cast light on a major puzzle of China's twentieth-century

history - the shifting convergence-cum-conflict between the industrial

and the social revolutions. No doubt two traditions - one, the scientific-

technological development of material things, the other, a moral crusade

to change social class structure - are interwoven in most revolutions.

But the tortuous gyrations of politics in recent decades suggest that

modern China lies peculiarly on a fault line between deep-laid continental

and maritime traditions.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER 2

ECONOMIC TRENDS, 1912-49

INTRODUCTION:

AN

OVERVIEW

To survey the history of the Chinese economy from the end of the Manchu

dynasty

to

the establishment

of

the People's Republic is inevitably

to

tell

a tale

in a

minor key. The years prior

to

1949 saw

no

'take-off'

towards

sustained growth

of

aggregate output

and the

possibility

of

increased

individual welfare that might accompany

it. At

best,

the

great majority

of Chinese merely sustained and reproduced themselves

at

the subsistence

level

to

which,

the

callous might say, they had long since become accus-

tomed.

In

the bitter decade

of

war and civil war which began

in

the mid

1930s,

the

standard

of

life

for

many fell short even

of

that customary

level.

1

A cautious weighing

of

what little

is

definitely known suggests that

aggregate output grew only slowly during 1912-49, and that there was no

increase

in per

capita income.

Nor was

there

any

downward trend

in

average income. Although

a

small modern industrial

and

transport

sector, which first appeared

in the

late nineteenth century, continued

to

grow

at a

comparatively rapid rate,

its

impact was minimal before 1949.

The relative factor supplies

of

land, labour and capital remained basically

unaltered.

The

occupational distribution

of the

population

was

hardly

changed;

nor in

spite

of

some expansion

of the

urban population

was

the urban-rural ratio significantly disturbed during these four decades.

While some

new

products were introduced from abroad

and

from

domestic factories, quantitatively they were

a

mere dribble,

and

they

scarcely affected

the

quality

of

life. Institutions

for

the creation

of

credit

remained

few and

feeble;

the

organization

of a

unified national market

was never achieved. Foreign trade

was

relatively unimportant

to the

majority

of the

population. Throughout rural China

a

demographic

1

This chapter excludes

any

consideration

of

communist-controlled China which included

areas

inhabited

by

some

90

million people

in

1945 and operated

in

part with different eco-

nomic

assumptions.

See

Peter Schran, Guerrilla

economy:

the

development

of

the

Shensi-Kansu-

Ninghsia border

region,

19)7-194J.

28

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION: AN OVERVIEW 29

pattern

of

high birth rates and high death rates persisted. Economic

hardship,

in

rural China in particular, was endemic, and probably grew

more critical after the outbreak

of

war in 1937. Yet in the absence of a

profound transformation

of

values

in a

significant portion

of

the elite

leadership

of

Chinese society, which led ultimately

to

the harnessing of

this distress to political ends not directly determined by the processes of

the economy

itself,

there is no good reason to believe that the economic

system would either have collapsed catastrophically or advanced rapidly

towards modern economic growth. As a system, China's economy which

was 'pre-modern' even in the mid twentieth century ceased to be viable

only after 1949

-

and then as a consequence of explicit political choice by

the victorious Communist Party and not primarily as

a

result

of

lethal

economic contradictions.

While the quantitative indicators do not show large changes during the

republican era, China

in

1949 was nevertheless different from China

in

1912.

The small industrial and transport sector and, perhaps even more,

the reservoir of technical skills and of experience with complex economic

organizations

-

the hundreds

of

thousands

of

workers, technicians and

managers who had themselves 'become modern'

-

provided

a

base upon

which the People's Republic could and did build.

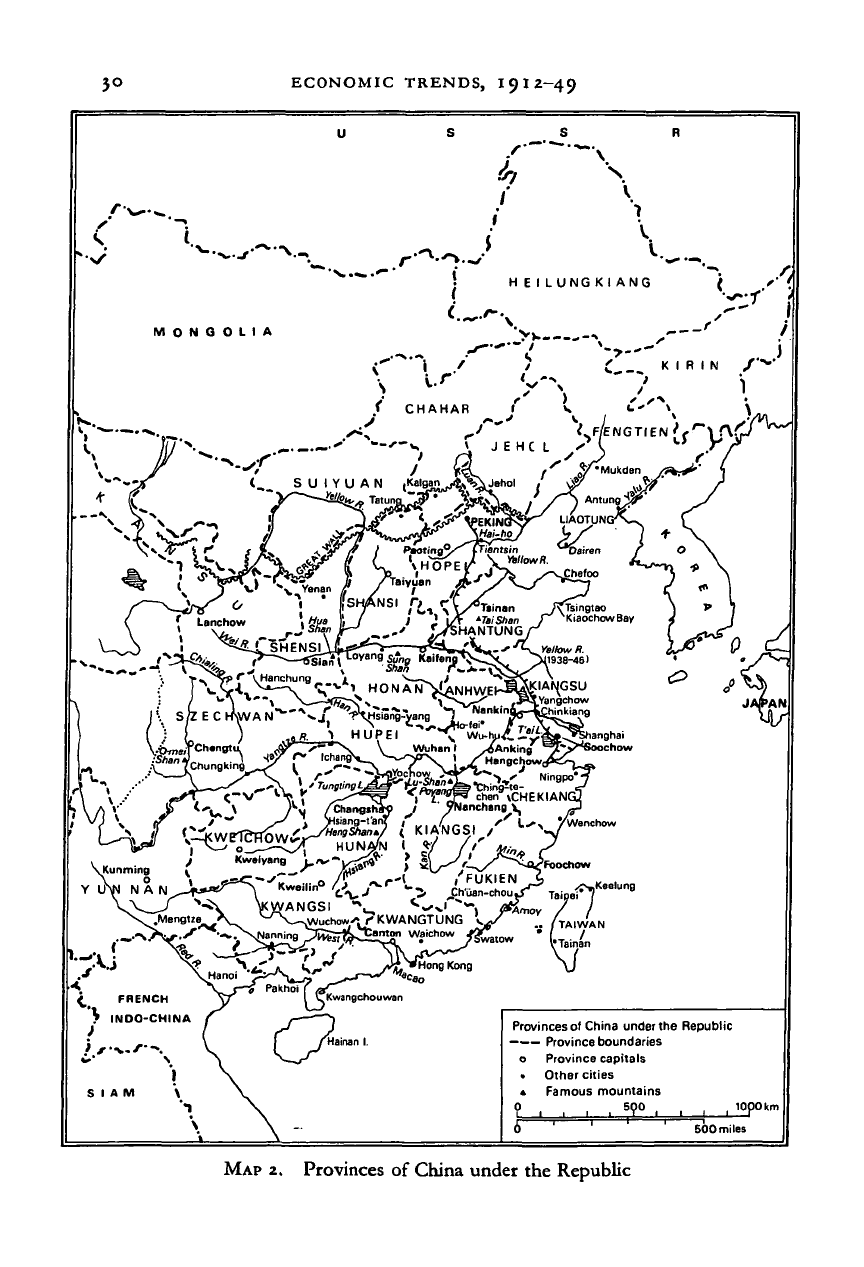

As

a

crude first approximation, the Chinese economy prior

to

1949

may be described as consisting

of a

large agricultural (or rural) sector

encompassing approximately 75 per cent of the population and

a

much

smaller non-agricultural (or urban) sector with its principal base in the

semi-modern treaty-port cities. Rural China grew the agricultural pro-

ducts which constituted 65 per cent

of

national output, and also made

use

of

the handicrafts, petty trade and old-fashioned transport.

To the

urban sector was attached, with ties of varying strength, an agricultural

hinterland. It was located mainly along rivers and railways leading to the

ports,

and may

be

differentiated from the mass

of

rural China

by

the

greater degree

to

which

it

traded with the coastal and riverine cities of

the urban sector.

The agricultural sector was composed mainly of

60

to 70 million family

farms.

Perhaps one-half were owner-operated, one-quarter were farmed

by part-owners who rented varying portions of their land, and the remain-

ing quarter was cultivated by tenant farmers. These families lived in the

several hundred thousand villages that filled most of the landscape of the

arable parts of China. In the course of the first half of the twentieth cen-

tury the average size of these farms decreased as the growth of popula-

tion exceeded the increments

to

arable land. Only

a

few areas

in

rural

China (in the regions

of

dense population) lacked agglomerated settle-

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

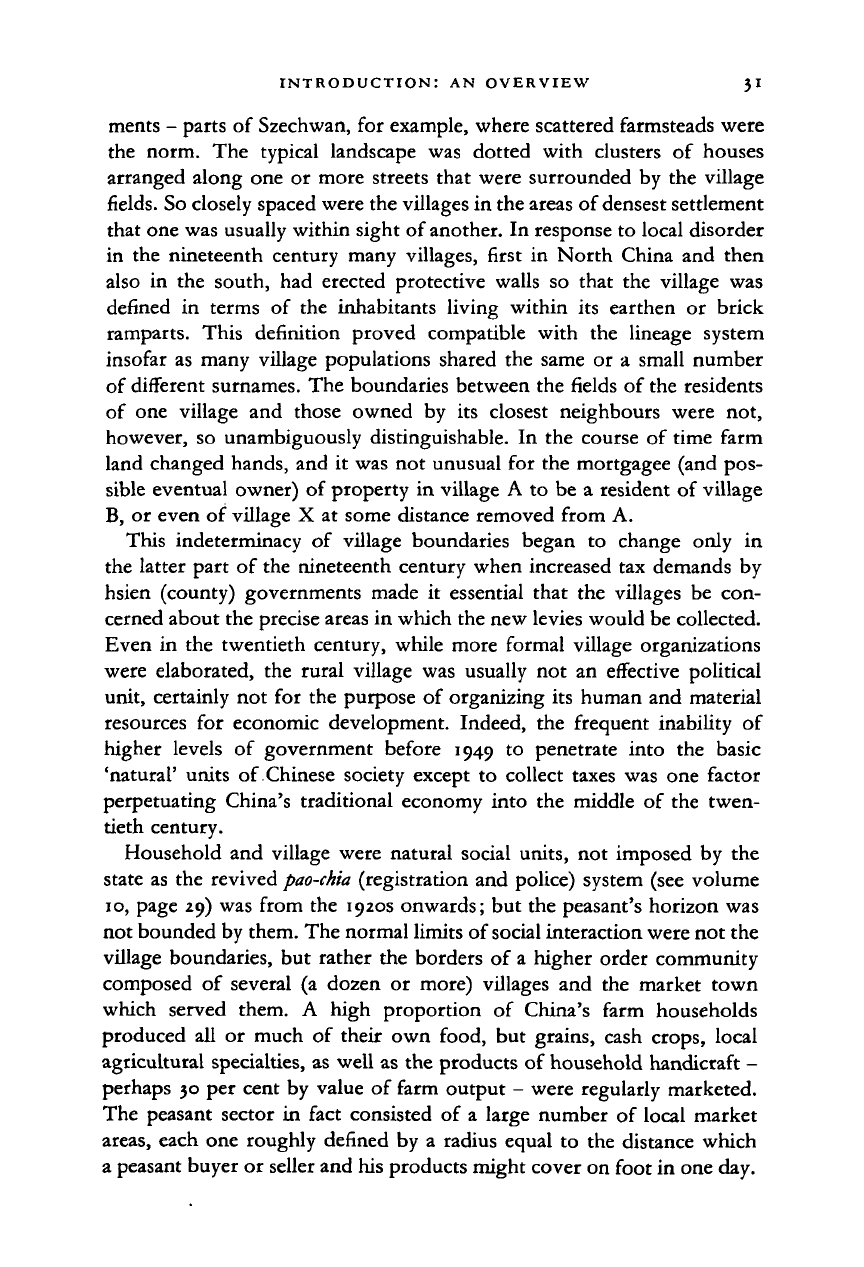

3°

ECONOMIC TRENDS, 1912-49

<

•>—/

MONGOLIA

\

La

C~ ^K-.--' iW®™

"^

van9

a?» *

ai

™r^

> T^f ^T

9

v

v

\

HONAFTVANHWES^^GSU

Provinces

of

China under the Republic

Province boundaries

o Province capitals

• Other cities

» Famous mountains

590

, , , 1

lOpOktn

500 miles

MAP

2.

Provinces

of

China under

the

Republic

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION: AN OVERVIEW 31

ments

-

parts of Szechwan, for example, where scattered farmsteads were

the norm. The typical landscape was dotted with clusters

of

houses

arranged along one or more streets that were surrounded by the village

fields. So closely spaced were the villages in the areas of densest settlement

that one was usually within sight of another. In response to local disorder

in the nineteenth century many villages, first

in

North China and then

also

in

the south, had erected protective walls

so

that the village was

defined

in

terms

of

the inhabitants living within

its

earthen

or

brick

ramparts. This definition proved compatible with

the

lineage system

insofar as many village populations shared the same or

a

small number

of different surnames. The boundaries between the fields of the residents

of one village and those owned

by its

closest neighbours were not,

however, so unambiguously distinguishable. In the course of time farm

land changed hands, and

it

was not unusual for the mortgagee (and pos-

sible eventual owner) of property in village A to be

a

resident of village

B,

or even of village X at some distance removed from A.

This indeterminacy

of

village boundaries began

to

change only

in

the latter part of the nineteenth century when increased tax demands by

hsien (county) governments made

it

essential that the villages be con-

cerned about the precise areas in which the new levies would be collected.

Even in the twentieth century, while more formal village organizations

were elaborated, the rural village was usually not

an

effective political

unit, certainly not for the purpose of organizing its human and material

resources

for

economic development. Indeed, the frequent inability

of

higher levels

of

government before 1949

to

penetrate into

the

basic

'natural' units

of

Chinese society except

to

collect taxes was one factor

perpetuating China's traditional economy into the middle

of

the twen-

tieth century.

Household and village were natural social units, not imposed by the

state as the revived

pao-chia

(registration and police) system (see volume

10,

page 29) was from the 1920s onwards; but the peasant's horizon was

not bounded by them. The normal limits of

social

interaction were not the

village boundaries, but rather the borders of a higher order community

composed

of

several

(a

dozen

or

more) villages and the market town

which served them.

A

high proportion

of

China's farm households

produced all

or

much

of

their own food, but grains, cash crops, local

agricultural specialties, as well as the products of household handicraft

-

perhaps 30 per cent by value of farm output

-

were regularly marketed.

The peasant sector in fact consisted

of

a large number of local market

areas,

each one roughly defined by

a

radius equal to the distance which

a peasant buyer or seller and his products might cover on foot in one day.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

32 ECONOMIC TRENDS, I912-49

The markets were normally periodic rather than continuous, occurring

every few days according to one

of

several scheduling systems that were

characteristic

of

different regions

in

China. Skinner, who refers

to

these

basic units as 'standard marketing areas' (SMA), has suggested that 'the

rural countryside

of

late traditional China can

be

viewed

as a

grid

of

approximately 70,000 hexagonal cells, each an economic system focused

on

a

standard market.'

2

The bulk of the trading in standard markets con-

sisted of a horizontal exchange of goods among peasants. To some extent

there was an upward flow out

of

the SMA

of

handicraft items and local

agricultural specialties; the principal outflow

of

staples, however, con-

sisted of tax grains to the government level of the economy. Increasingly

in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries the SMA was the ultimate

destination

of

new commodities either manufactured

in

the treaty ports

or imported from abroad.

To

the

limited extent that rural China began

to

produce staples

for

export, including technical crops for the treaty-port factories, these tended

to move in new commercial channels alternative to the traditional periodic

markets.

In

the agricultural hinterland

of

the east coast treaty ports,

in

particular,

a

modern town economy developed alongside the periodic-

marketing economy. But

in

the vast area

of

rural China the traditional

market structure was flourishing with few signs

of

decay right down

to

1949,

a

strong indication that

the

rural economy

had not

been

sub-

stantially transformed. The peasant household in the mid twentieth century

probably depended more

on

commodities not produced

by

itself or

by

its neighbours than was the case 50 years earlier. But, because there was

little real improvement

in

transportation

at

the local level, the primary

marketing area was not enlarged

so as to

bring about

a

radical replace-

ment

of

standard markets

by

modern commercial channels organized

around larger regional marketing complexes.

Non-agricultural,

or

'urban', does

not

necessarily imply 'modern'.

At the beginning

of

the nineteenth century perhaps

as

many

as

12 mil-

lion people,

3 to 4

per cent

of

the then 350 million Chinese, lived

in

cities with populations

of

30,000

or

more. With few exceptions, these

cities were primarily administrative centres

-

the national capital, Peking,

with nearly one million inhabitants, major provincial capitals, and

the

largest prefectural (Ju) cities. Some were simultaneously important centres

of inter-provincial and inter-regional commerce like Nanking, Soochow,

Hankow, Canton, Foochow, Hangchow, Chungking, Chengtu and Sian.

These cities were the loci of the highest officials of the empire, the major

2

G.

William Skinner, 'Marketing and social structure

in

rural China',

pt

I,

JAS,

26.1 (Nov.

1964) 3-44.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008