The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC POLICIES 453

Much more worrisome was the recruitment of Chinese forces. Khubilai

could not afford to rely excessively on the Chinese and needed to balance

them with Mongolian troops. Accordingly, as bodyguards for himself and for

the court, he employed the Mongol kesig. Similarly, in stationing garrisons

along the borders, he sensed the need to maintain Mongolian dominance

among those troops.

Khubilai recognized, too, that Mongolian control of military supplies and

equipment was essential. The court, for example, prohibited the Chinese

from buying and selling bamboo, which could be used for bows and arrows;

bamboo was monopolized by the court.

6

3 Khubilai also sought to guarantee

for the court a dependable supply of horses suitable for warfare. As the

Mongols in China began to settle in the sedentary world, they faced the same

problems as did the Chinese in acquiring horses. To provide the government

with the horses it required, Khubilai ordered that one out of every hundred

horses owned by Chinese subjects be turned over to the court. He also

reserved the right to purchase horses, compelling the owners to sell their

animals at official prices. Chinese families who attempted to conceal their

steeds or who sold them privately would be severely punished. The govern-

ment agency known as the Court of the Imperial Stud cared for its horses and

managed its pasturelands, which were concentrated in Mongolia, north and

northwest China, and Korea. Though the sources occasionally refer to horse

smuggling and other abuses, the court, during Khubilai's reign, had access

to a sufficient number of horses.

64

Another of the court's concerns was the creation of a legal code for its

domain. The jasagh, the traditional Mongolian legal regulations, lacked the

sophistication necessary to rule a sedentary civilization; rather, it reflected

the values of a nomadic society and was unsuited to China. On coming to

power, Khubilai retained the law code of the Jurchen Chin dynasty, but by

1262 he ordered Yao Shu and Shih T'ien-tse, two of his most trusted and

influential advisers, to devise a new code that was more suitable for his

Chinese subjects. These laws began to be implemented in 1271, but Mongo-

lian laws, practices, and customs affected this new code.

The Mongols apparently introduced greater leniency into the Chinese legal

system. The number of capital crimes amounted to 135, less than one-half

the number mandated in the Sung dynasty codes. Criminals could, following

Mongolian practice, avoid punishment by paying a sum to the government.

Khubilai could grant amnesties, and he did so, even to rebels or political

63 Inosaki Takaoki, "Gendai no take no sembaiken to sono shiko sum igi,"

Toyoshi

kmkyu, 16 (September

'957).

PP- 29-47-

64 Ta Yuan ma

cheng

chi (Peking, 1937), pp. 1—3; C. R. Bawden and S. Jagchid, "Some notes on the

horse policy of the Yiian dynasty," Central Asiatic Journal, 10 (1965), pp. 261-3.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

454

THE

REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

enemies. Officials of the provincial or central government routinely reviewed

local judicial decisions on serious crimes in order to prevent abuses of the

rights of the accused. Because there have not been any careful studies of this

code in operation, it is difficult to tell whether these statutory reforms

translated into a more lenient and flexible system than under the earlier

Chinese dynasties. Yet the legal ideals embodied in this code supported by

Khubilai and the Mongols did indeed appear less harsh than earlier Chinese

ones.

6

'

KHUBILAI AS EMPEROR OF CHINA

Though Khubilai wished to be considered as more than the emperor of

China, he was unable to coerce the other khans into accepting his authority.

As the khaghan of the Mongols, he aspired to universal rule and sought

recognition of his status as the undisputed ruler of all the Mongolian do-

mains. The Golden Horde in Russia had supported Arigh Boke's candidacy

as the khaghan and were not reconciled to Khubilai's victory. Khaidu, who

controlled the Chaghadai khanate of Central Asia, was an implacable foe of

Khubilai's. Only Khubilai's brother Hiilegii, the founder of the Ilkhanate of

Persia, and his descendants accepted Khubilai as khaghan, but they were

essentially self-governing. The Golden Horde and the Ilkhans were entan-

gled in their own conflict over their claims to the pasturelands of Azerbaijan,

diverting attention from their relationships with the khaghan.

With such limited acceptance of his position as khaghan, Khubilai increas-

ingly became identified with China and sought support as emperor of China.

In order to attract the allegiance of the Chinese, he needed to portray himself

as and to act like a traditional Chinese emperor. He would have to reinstate

some of the Confucian rituals and practices if

he

hoped to attract the support

or at least the acquiescence of the Chinese scholar-officials or the elite.

Khubilai remained a Mongol and would not abandon Mongolian values, yet

he recognized that he had to make some adjustments to garner such support.

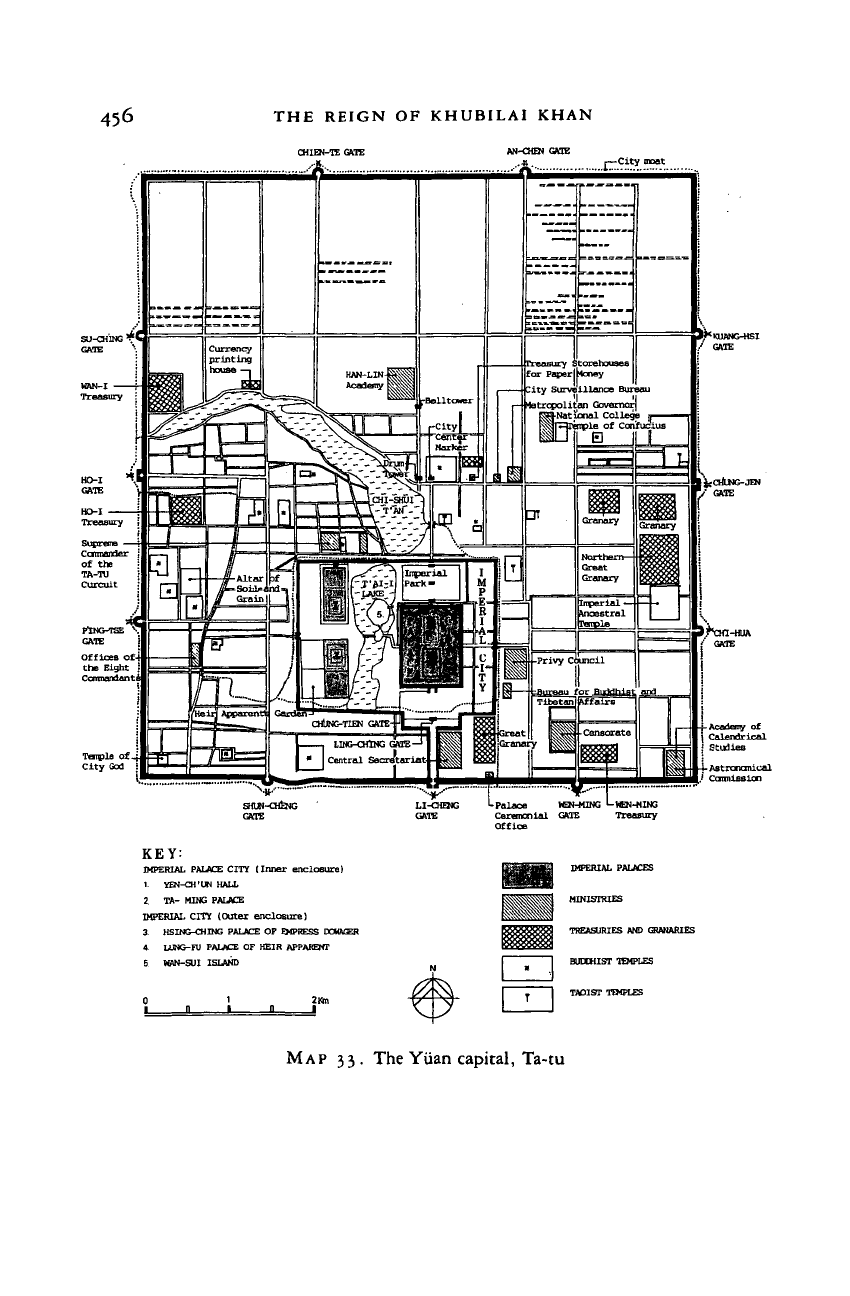

Khubilai's clearest signal to his Chinese subjects was his shift of the capital

from Mongolia to north China. With the assistance of his adviser Liu Ping-

chung, he conceived of the idea of moving the capital from Khara Khorum to

the modern city of Peking. In 1266, he ordered the construction of a city

that came to be known as Ta-tu (great capital) to the Chinese and as

Khanbalikh (city of the khans) to the Turks. The Mongols called it Daidu, a

transliteration directly from the Chinese. Though a Muslim supervised the

65 Paul Heng-chao Ch'en, Chinese legal tradition under the Mongols: The code of 1291 as

reconstructed

(Princeton, 1979), p. xix, argues generally that the Yuan code was indeed more lenient and flexible

than were earlier Chinese codes.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

KHUBILAI AS EMPEROR OF CHINA 455

whole project and numerous foreign craftsmen took part in the construction,

the city was Chinese in conception and style. The planners followed Chinese

models, as Khubilai wanted Ta-tu to serve as a symbol of

his

efforts to appeal

to the traditional Chinese scholars and Confucians. He chose, however, to

build the capital on an unconventional site. Unlike earlier Chinese capitals

that were, for the most part, situated near the Yellow River or one of its

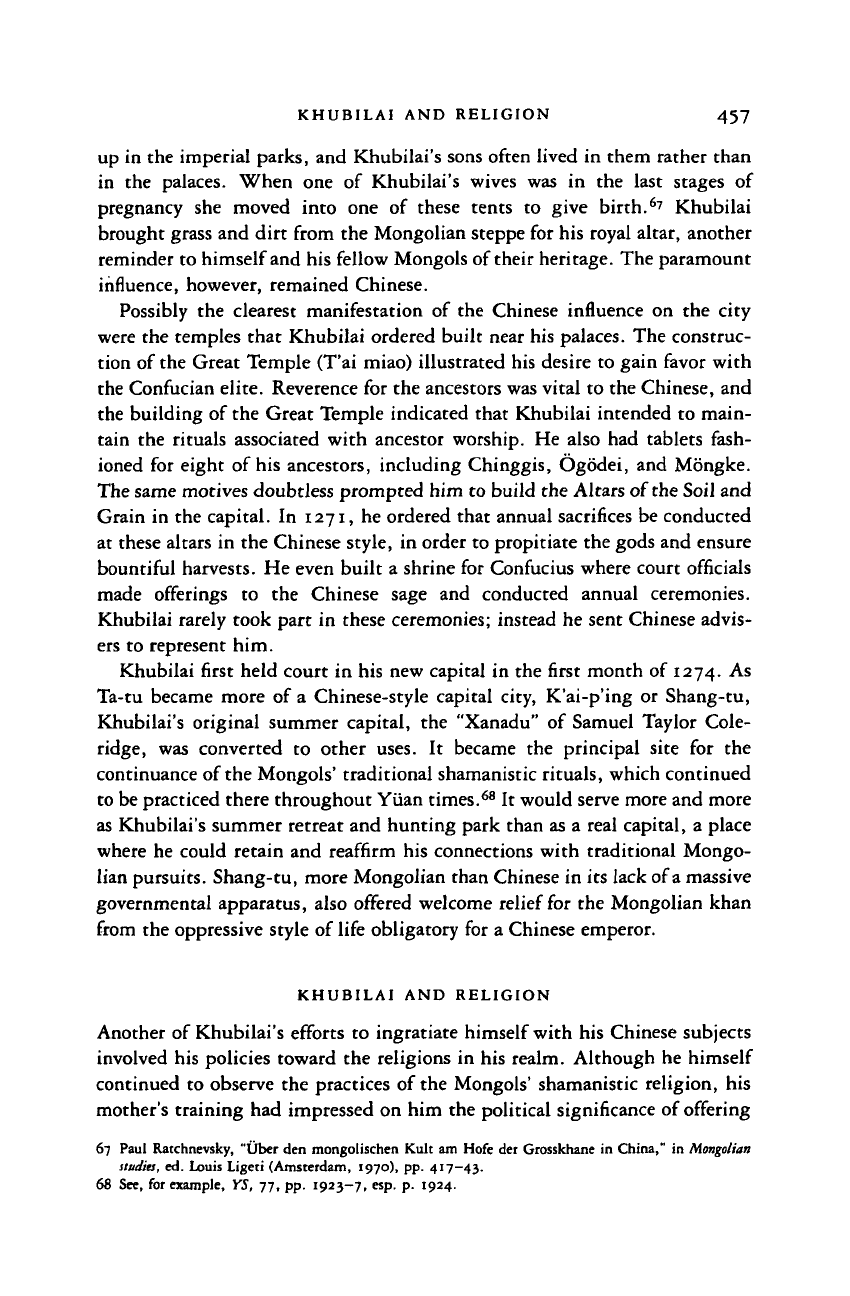

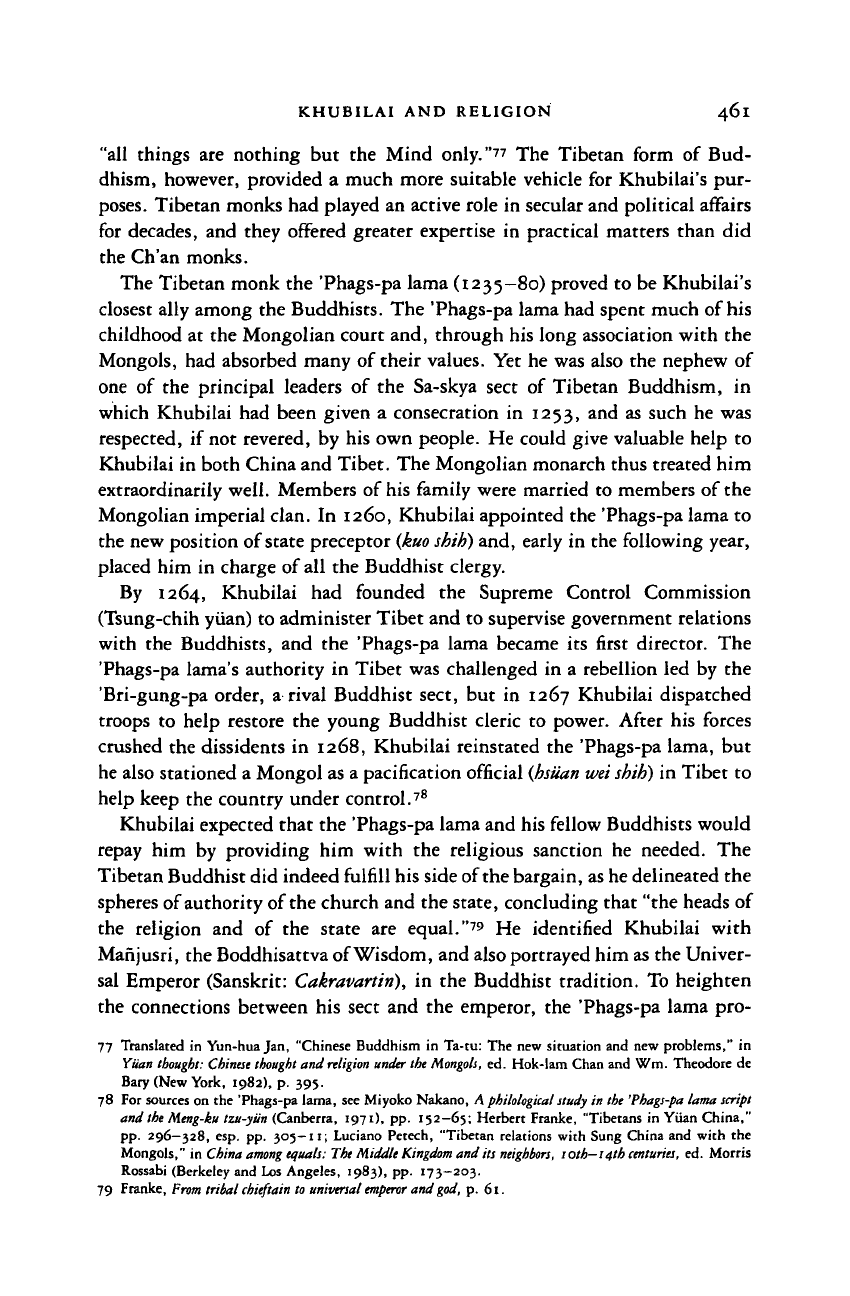

tributaries, Ta-tu was located close to China's northern border (see Map 33).

Khubilai selected this site, which had been the site of the Liao and Chin

capitals, partly because he perceived that his domains included more than

just China and partly because he wished to retain control over his homeland

in Mongolia. An administrative center in north China would offer him a

listening post and a base from which to assert his authority over his native

land. Ta-tu's major deficiency was its inadequate reserves of grain. To cope

with this shortage, Khubilai imported vast quantities of food from south

China and eventually lengthened the Grand Canal to reach all the way to the

capital.

The Muslim architect Yeh-hei-tieh-erh and his associates constructed Ta-

tu as a typical Chinese capital, albeit with some Mongolian touches. The city

was rectangular and enclosed by a wall of rammed earth. Within this outer

wall were two inner walls surrounding the Imperial City and Khubilai's

residences and palaces, to which ordinary citizens were denied entry. The city

was laid out on symmetrical north—south and east—west axes, with wide

avenues stretching in geometric patterns from the eleven gates that permitted

access into the city. The avenues were broad enough so that "horsemen can

gallop nine abreast." On all the gates were three-story towers that served to

warn of impending threats or dangers to the city.

66

All of the buildings in the

Imperial City, the khan's own quarters and those of his consorts and concu-

bines and the hall for receiving foreign envoys, as well as the lakes, gardens,

and bridges, were remarkably similar to those in a typical Chinese capital.

Yet Mongolian decor was evident in some of the buildings. In Khubilai's

sleeping chambers hung curtains and screens of ermine skins, a tangible

reminder of the Mongols' hunting life-style. Mongolian-style tents were set

66 Two fourteenth-century sources, the Nan ts'un

ch'o

keng lu by T'ao Tsung-i and the Ku kung i lu by

Hsiao Hsiin, offer useful descriptions of the layout and the actual buildings of Peking at that time.

Nancy Schatzman Steinhardt used these two texts in her "Imperial architecture under Mongolian

patronage: Khubilai's imperial city of Daidu" (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University, 1981). See also her

article "The plan of Khubilai Khan's imperial city," Artiiui Asiae, 44 (1983), pp. 137-58. Chinese

archaeologists have also begun to explore some of the remains of the Mongols' capital of Ta-tu (Daidu).

For examples of their recent discoveries, see Yuan Ta-tu k'ao ku tui, "Yuan Ta-tu te k'an ch'a ho fa

chiieh," K'ao ku, 1 (1972), pp. 19-28; Yuan Ta-tu k'ao ku tui, "Chi Yuan Ta-tu fa hsien te Pa-ssu-pa

tzu wen wu," K'ao ku, 4 (1972), pp. 54—7; Yuan Ta-tu k'ao ku tui, "Pei-ching Hou Ying-fang Yuan

tai chii chu i chih," K'ao ku, 6 (1972), pp. 2-15; Chang Ning, "Chi Yuan Ta-tu ch'u tu wen wu," Kao

ku,

6 (1972), pp. 25-34.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

456

THE REIGN

OF

KHUBILAI KHAN

Tsnple of-j

City God

:ity Surveillance Bureau

'I

'I

tropolitan Governor]

i- Ast ronanical

,' Caimissicn

LI-CHENG

L

Palace HEN-MING

L

HEN-MING

GATE Ceremonial GATE

Treasury

Office

KEY:

IMPERIAL PALACE CITY (Inner enclosure)

1.

YEN-CH'UN HALL

2.

TA- MING PALACE

IMPERIAL

cm

(Outer enclosure)

3.

HSING-CHING PALACE OP EMPRESS DOWMER

4 LUHG-FU PALACE OF HEIR APPARENT

5 WAN-SUI ISLAND

MAP

33

.

The Yiian capital, Ta-tu

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

KHUBILAI AND RELIGION 457

up in the imperial parks, and Khubilai's sons often lived in them rather than

in the palaces. When one of Khubilai's wives was in the last stages of

pregnancy she moved into one of these tents to give birth.

67

Khubilai

brought grass and dirt from the Mongolian steppe for his royal altar, another

reminder to himself and his fellow Mongols of their heritage. The paramount

influence, however, remained Chinese.

Possibly the clearest manifestation of the Chinese influence on the city

were the temples that Khubilai ordered built near his palaces. The construc-

tion of the Great Temple (T'ai miao) illustrated his desire to gain favor with

the Confucian elite. Reverence for the ancestors was vital to the Chinese, and

the building of the Great Temple indicated that Khubilai intended to main-

tain the rituals associated with ancestor worship. He also had tablets fash-

ioned for eight of his ancestors, including Chinggis, Ogodei, and Mongke.

The same motives doubtless prompted him to build the Altars of the Soil and

Grain in the capital. In 1271, he ordered that annual sacrifices be conducted

at these altars in the Chinese style, in order to propitiate the gods and ensure

bountiful harvests. He even built a shrine for Confucius where court officials

made offerings to the Chinese sage and conducted annual ceremonies.

Khubilai rarely took part in these ceremonies; instead he sent Chinese advis-

ers to represent him.

Khubilai first held court in his new capital in the first month of 1274. As

Ta-tu became more of a Chinese-style capital city, K'ai-p'ing or Shang-tu,

Khubilai's original summer capital, the "Xanadu" of Samuel Taylor Cole-

ridge, was converted to other uses. It became the principal site for the

continuance of

the

Mongols' traditional shamanistic rituals, which continued

to be practiced there throughout Yuan times.

68

It would serve more and more

as Khubilai's summer retreat and hunting park than as a real capital, a place

where he could retain and reaffirm his connections with traditional Mongo-

lian pursuits. Shang-tu, more Mongolian than Chinese in its lack of a massive

governmental apparatus, also offered welcome relief for the Mongolian khan

from the oppressive style of life obligatory for a Chinese emperor.

KHUBILAI AND RELIGION

Another of Khubilai's efforts to ingratiate himself with his Chinese subjects

involved his policies toward the religions in his realm. Although he himself

continued to observe the practices of the Mongols' shamanistic religion, his

mother's training had impressed on him the political significance of offering

67 Paul Ratchnevsky, "Uber den mongolischen Kult am Hofe der Grosskhane in China," in Mongolian

studies, ed. Louis Ligeti (Amsterdam, 1970), pp. 417-43.

68 See, for example, YS, 77, pp. 1923—7, esp. p. 1924.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

458 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

patronage and support for the leading religions in a newly conquered land.

In

the 1260s, Khubilai needed to devise a relationship with the various Chinese

religions that buttressed his position

as

ruler

of

China and hence ensured

Mongolian control

of

the country. Even before he assumed the title of em-

peror, he had attempted to appeal to Chinese religious dignitaries, but now

his efforts took on greater significance and urgency.

Khubilai wished, first of all,

to

cultivate good relations with the Confu-

cians.

By

1267, the year the construction of Ta-tu began, he had ordered the

building of the Imperial Ancestral Temple (T'ai-miao) and the preparation of

ancestral tablets

for the

practice

of

dynastic ancestor worship, and

he

had

designated

a

calendar for the country, a vital task for the ruler of

an

agricul-

tural society.

His

selection

of a

name

for his

dynasty would

be an all-

important signal

to

Confucians. The adoption

of a

Chinese name rich

in

Chinese symbolism would indicate that Khubilai wished to blend with some

Chinese traditions.

In

1271, Khubilai,

at Liu

Ping-chung's suggestion,

chose the name Ta Yiian from the

/

ching

(Book of

changes).

Yiian referred to

the "origins of the Universe" or "the primal force," but most important, this

name for the new dynasty had direct associations with one of

the

works of the

Chinese canonical tradition. ^

In the same year, Khubilai reinstituted

at

the court the traditional Confu-

cian rituals and their accompanying music and dance. Proper performance of

these rituals was essential if the court was to avert imbalances

in

nature that

led

to

floods, droughts,

or

earthquakes. Khubilai

not

only ordered their

reintroduction but also had his Confucian advisers teach the ceremonies to

a

selected group of about two hundred Mongols, another telling indication of

his desire to ingratiate himself with the Chinese.

70

Further proof of Khubilai's sensitivity to Confucianism and Chinese values

may

be

gleaned from

the

training and education that he prescribed

for his

second son, whom he eventually designated as his successor. With the help of

the Buddhist monk Hai-yiin, he had chosen a Chinese Buddhist name, Chen-

chin (True gold),

for

this son.

71

Determined that Chen-chin receive

a

first-

rate Chinese education, he assigned Mao Shu, Tou Mo,

and

Wang Hsiin,

three

of

his most prized Confucian advisers,

to

tutor the young man. These

learned men introduced Chen-chin to the Chinese classics and presented him

with

an

essay summarizing the political views of some

of

the emperors and

ministers of earlier Chinese dynasties.

69 Maurizia Dinacci Saccheti, "Sull'adozione del nome dinastico Yiian," Annali

htituto

OrientatediNapoli,

31,

n.s. 21 (1971), pp. 553-8.

70

YS,

67, pp. 1665-6; 88,

p.

2217.

71 This name

is

sometimes given the Mongolian reading "Jingim," but strictly speaking, this is incor-

rect.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

KHUBILAI AND RELIGION 459

Khubilai also ensured that his young son was exposed to the other reli-

gions and cults in his Chinese domain. Chen-chin thus received instruction

from a Buddhist monk, the 'Phags-pa lama, who wrote a brief work entitled

Ses by a rab-gaal (What one should know), to offer his young student a

description of Buddhism.'

2

A leading Taoist master provided him with an

introduction to that mystical religion. Pleased with Chen-chin's growing

acceptance by the Chinese, Khubilai gave his son ever-increasing responsibili-

ties and repeatedly promoted him, culminating in 1273 with the designation

of Chen-chin as heir apparent. In so designating his own successor, Khubilai

made a complete break with Mongolian custom, by preempting the normal

process of election, and followed the normal procedure of a standard Chinese

dynasty.

Still another way of attracting the Confucian scholars was to provide

tangible support for the propagation of their views. Khubilai promoted, for

example, the translation of Chinese works into Mongolian. Such Confucian

classics as the Hsiao ching (Book of filial piety) and the Shu-ching (Book of

documents), as well as Neo-Confucian writings such as the

Ta-hsueh

yen-i by

Chen Te-hsiu (1178—1235), were translated under Khubilai's patronage.

73

By making these texts available to the Mongolian elite, Khubilai showed the

Chinese that he respected Confucian ideas. He also impressed the Chinese

scholars by recruiting some prominent literati to teach their own people as

well as Mongols and Central Asians. One of the most renowned such recruits

was Hsu Heng (1209-81) whom Khubilai appointed chancellor of the Impe-

rial College in 1267. Hsu, universally recognized as one of the greatest

scholars of his age, pleased his Mongolian patron because in his teaching he

concentrated on practical affairs. He succeeded because he "did not go into

speculative, metaphysical matters or 'things on the higher level.' "

74

In his

advice to Khubilai, he emphasized pragmatic considerations, an attitude

certain to gain him favor at the Mongolian court.

Khubilai's favorable reaction to suggestions for writing a dynastic history

in the traditional Chinese style also met with the Confucians' approval.

Confucianism, with its emphasis on the past and on the use of historical

models as guides to behavior, provided an impetus to such officially endorsed

historiographical projects. In August 1261, the Confucian scholar Wang O

(1190—1273) proposed that the historical records of the Liao and Chin dynas-

72 Constance Hoog, trans., Prince Jin-gim's

textbook

of

Tibetan

Buddhism (Leiden, 1983); Herbert Franke,

"Tibetans in Yuan China," in China

under Mongol

rule,

ed. John D. Langlois, Jr. (Princeton, 1981), p.

307.

73 Walter Fuchs, "Analecta zur mongolischen Ubersetzungsliceratur der Yiian-Zeit,"

Monumenta

Serica,

11 (1946), pp. 33-64.

74 Wing-tsit Chan, "Chu Hsi and Yuan Neo-Confucianism," in Yuan

thought:

Chinese thought

and

religion

under

the

Mongols,

ed. Hok-lam Chan and Wm. Theodore de Bary (New York, 1982), p. 209.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

460 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

ties,

as well as those of the early Mongolian rulers, be collected.

7

' He also

suggested that the court establish a History Office under the Han-lin Acad-

emy (to be known as the Han-lin kuo-shih yuan) to assemble the records and

then compose the histories of the Liao and Chin dynasties. Khubilai, who

ostensibly did not share the Chinese enthusiasm for historical writing, none-

theless approved the founding of

a

History Office, another decision by which

he hoped to gain the approval of the Confucians.

Khubilai naturally needed to appeal to religions and cults other than

Confucianism if he wished to be perceived as the ruler of

China.

One of the

religious groups that he was especially anxious to influence was the Muslims.

Islam had reached China as early as the T'ang dynasty, and by Khubilai's

time,

Muslim merchants, craftsmen, and soldiers - most of them immi-

grants from Central Asia, but some of them Chinese converts to Islam

—

were

to be found throughout the country, though they tended to be concentrated

in the northwest and southeast. Khubilai pursued a benevolent policy toward

the Muslims because they were useful to him in governing China. By recruit-

ing Muslims for his government, Khubilai made himself less dependent on

Chinese advisers and officials. He thus permitted them to form virtually

self-

governing communities with a

shaikh al-lslam

(Chinese:

hui-hui

t'ai-shih)

as

their leader and a qadi (Chinese:

hui-chiao-t'u fa-kuan)

as their interpreter of

Muslim laws. The Muslim quarters had their own bazaars, hospitals, and

mosques, and they were not prevented from using their native languages or

following the dictates of Islam. Khubilai, in fact, appointed Muslims to

important positions in the financial administration and accorded them spe-

cial privileges. He exempted them from regular taxation and recruited them

as

darughachi

(commissioners), a position that few Chinese could hold. The

Muslims were grateful and responded by loyally serving the court. The most

renowned of these Muslims was Saiyid Ajall Shams al-DIn, from Bukhara,

who was appointed in 1260 as pacification commissioner of a district in north

China and eventually wound up as the governor of

the

southwestern province

of Yunnan.

76

The Buddhists were still another group whose support Khubilai wished to

cultivate. As early as the 1240s, he himself had received instruction from the

Ch'an Buddhist monk Hai-yiin, but he had soon found Ch'an Buddhism too

abstruse and unworldly for his purposes. It appeared to lack any concern for

practical affairs, as, for example, when a Ch'an master had told Khubilai that

75 Hok-lam Chan, "Wang O (1190-1273),"

Papers

on Far

Eastern

History, 12 (1975), pp. 43—70, and

"Chinese official historiography at the Yuan court: The composition of the Liao, Chin, and Sung

histories," in China under

Mongol

rule,

ed. John D. Langlois, Jr. (Princeton, 1981), pp. 56—106, esp.

pp.

64—6.

76 Rossabi, "Muslims in the early Yuan dynasty," pp. 258-99.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

KHUBILAI AND RELIGION 461

"all things

are

nothing

but the

Mind only."

77

The

Tibetan form

of

Bud-

dhism, however, provided

a

much more suitable vehicle

for

Khubilai's pur-

poses.

Tibetan monks had played an active role

in

secular and political affairs

for decades,

and

they offered greater expertise

in

practical matters than

did

the Ch'an monks.

The Tibetan monk the 'Phags-pa lama (1235-80) proved

to

be Khubilai's

closest ally among the Buddhists. The 'Phags-pa lama had spent much of his

childhood

at

the Mongolian court and, through his long association with the

Mongols, had absorbed many

of

their values. Yet he was also the nephew

of

one

of the

principal leaders

of

the Sa-skya sect

of

Tibetan Buddhism,

in

which Khubilai

had

been given

a

consecration

in

1253, and

as

such he was

respected,

if

not revered,

by

his own people. He could give valuable help

to

Khubilai

in

both China and Tibet. The Mongolian monarch thus treated him

extraordinarily well. Members

of

his family were married

to

members of the

Mongolian imperial clan.

In

1260, Khubilai appointed the 'Phags-pa lama

to

the new position of state preceptor

(kuo

shih) and, early

in

the following year,

placed him

in

charge of all the Buddhist clergy.

By

1264,

Khubilai

had

founded

the

Supreme Control Commission

(Tsung-chih yuan) to administer Tibet and to supervise government relations

with

the

Buddhists,

and the

'Phags-pa lama became

its

first director.

The

'Phags-pa lama's authority

in

Tibet was challenged

in a

rebellion led

by the

'Bri-gung-pa order,

a

rival Buddhist sect,

but in

1267 Khubilai dispatched

troops

to

help restore

the

young Buddhist cleric

to

power. After his forces

crushed the dissidents

in

1268, Khubilai reinstated the 'Phags-pa lama,

but

he also stationed

a

Mongol as

a

pacification official

(hsiian wet

shih)

in

Tibet

to

help keep the country under control.

78

Khubilai expected that the 'Phags-pa lama and his fellow Buddhists would

repay

him by

providing

him

with

the

religious sanction

he

needed.

The

Tibetan Buddhist did indeed fulfill his side of the bargain, as he delineated the

spheres of authority of the church and the state, concluding that "the heads of

the religion

and of the

state

are

equal."

79

He

identified Khubilai with

Mafijusri, the Boddhisattva of Wisdom, and also portrayed him as the Univer-

sal Emperor (Sanskrit: Cakravartin),

in the

Buddhist tradition. To heighten

the connections between

his

sect and the emperor,

the

'Phags-pa lama pro-

77 Translated

in

Yun-hua Jan, "Chinese Buddhism

in

Ta-tu: The new situation and new problems,"

in

Yuan

thought:

Chinese thought

and

religion under

the

Mongols,

ed.

Hok-lam Chan and Wrn. Theodore

de

Bary (New York, 1982),

p. 395.

78 For sources on the 'Phags-pa lama, see Miyoko Nakano,

A

philological

study in the

'Phags-pa

lama script

and the Meng-tu tzu-yun (Canberra, 1971), pp. 152—65; Herbert Franke, "Tibetans

in

Yuan China,"

pp.

296—328, esp.

pp.

305—11; Luciano Petech, "Tibetan relations with Sung China and with

the

Mongols,"

in

China

among

equals:

The Middle

Kingdom

and its

neighbors,

10th—

14th

centuries,

ed.

Morris

Rossabi (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1983), pp. 173—203.

79 Franke,

From

tribal

chieftain

to universal

emperor

and

god,

p. 61.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

462 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

posed the initiation of court rituals associated with Buddhism. Annual proces-

sions and parades, which

were

designed to destroy the "demons" and

to

protect

the state, were organized

on

the

fifteenth

day of the second month, and music,

rituals, and parades also were scheduled in the first and sixth months of the

year. The Buddhist clergy's participation in these ceremonies offered Khubilai

greater credibility with the Buddhists in his domains.

Khubilai, in turn, rewarded the Buddhists with special privileges and

exemptions. Buddhist monks were granted a tax-exempt status for much of

his reign; the court supplied funds for the construction of new monasteries

and temples as well as for the repair for some that had been damaged during

the Buddhist—Taoist disputes; and the government provided artisans and

slaves to work in the craftshops and on the lands owned by the monasteries.

80

Government support, subsidies, and exemptions enabled the monasteries and

temples to become prosperous economic centers and helped ensure Buddhist

support for Khubilai's policies.

Taoism was still another of the religions from which Khubilai sought

sanction and assistance. Khubilai's support for the Buddhists in their debate

with the Taoists in 1258 had not endeared him to the Taoist hierarchy. Yet he

was entranced by their reputed magical powers and recognized their strong

appeal to the lower classes. The court thus provided monies for the construc-

tion of Taoist temples and offered them some of the same exemptions and

privileges that it had accorded to the Buddhists. A few of the Taoist leaders

recognized the need for an accommodation with the Buddhists and the

Mongols and sought first to reconcile the three teachings of Confucianism,

Buddhism, and Taoism. Later they served Khubilai and his court by perform-

ing the sacrifices and ceremonies associated with the Taoist cults, in particu-

lar the worship of T'ai-shan, a vital imperial cult. Their willingness to

conduct these ceremonies for Khubilai signaled a kind of support that was

transmitted to ordinary believers in Taoism, and the Taoists remained rela-

tively quiescent for the first two decades of Khubilai's reign.

Khubilai and

the Western

Christians

Khubilai even sought to secure support and assistance from the small Chris-

tian population within China, as well as from foreign Christians. Christian

emissaries, such as John of Piano Carpini and William of Rubruck, had

reached the Mongolian court during the reigns of Khubilai's predecessors,

and several craftsmen, such

as

the renowned artisan Guillaume Boucher, had

80 Nogami Shunjo, "Gcndai dobutsu nikyo no kakushitsu,"

Otam daigaku kcnkyv

nempo,

2 (1943), pp.

230—1;

Paul Ratchnevsky, "Die mongolische Grosskhane und die buddhiscische Kirche," in

Asiatica:

Festschrift Friedrich Wtller

zum 6}.

Geburtstag,

ed. Johannes Schubert (Leipzig, 1954), pp. 489—504.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008