The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ECONOMIC PROBLEMS IN LATER YEARS 473

culture that no doubt added to Khubilai's luster as a ruler of a realm not

confined merely to China.

ECONOMIC PROBLEMS IN LATER YEARS

The year 1279 proved to be a watershed in Khubilai's reign. Until that time,

he had scarcely experienced any failures in his undertakings. He had crushed

all opposition, including that of his younger brother. He and his advisers had

established a government based on Chinese models but not dominated by

Chinese ideals and forms. His two capitals at Shang-tu and Ta-tu were well

planned, functional, and beautiful. He had, through a carefully considered

policy, gained favor with most of the religious leaders in his realm. His armies

had conquered the rest of China and had asserted Mongolian control over Korea

and Mongolia. He had encouraged the creative arts and had recruited some of

the ablest artisans in the land to produce exquisite articles for the court and the

elite and for use in foreign trade. His most conspicuous failure had been his

abortive invasion of Japan, but he could rationalize this defeat by blaming it on

the natural disaster, the terrible storm, that devastated his forces. All else in

the first two decades of his reign seemed to be proceeding smoothly.

But appearances were deceptive. Some difficult problems lay beneath the

surface. Some Confucian scholars were not reconciled to Mongolian rule, and

their dissatisfaction became even more pronounced with the amalgamation of

the Southern Sung into the Yuan domains. The scholars in the south had not

experienced foreign domination, and quite a few eventually refused to collabo-

rate with the Mongols. Khubilai himself began to slow down after 1279.

Now in his late sixties, he was afflicted with health problems. Gout plagued

him and made it difficult for him to walk.

The most pressing problem that Khubilai faced was finances. His construc-

tion projects, his support for public works, and his military expeditions

entailed vast expenditures. To obtain the needed funds, Khubilai turned to

the Muslim finance minister Ahmad, whom the Yuan dynastic history classi-

fies as one of the "villainous ministers" and who is reviled by both Chinese

and Western sources.

102

In his defense, we should recognize that Ahmad

knew that he would be judged by the amount of revenue he collected for the

court. The more funds he raised, the greater his power, prestige, and income

would be. He surely profited from his position, but it must be remembered

that his accusers (those who wrote the Chinese accounts) were officials unsym-

pathetic to his policies.

102 Herbert Franke, "Ahmed: Ein Beitrag zur Wirtschaftsgeschichte Chinas untet Qubilai," Orient, 1

(1948),

pp. 222-36.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

474 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

From 1262, when he was apppointed to the Central Secretariat, until his

death in 1282, Ahmad directed the state financial administration. He first

increased the number of households on the tax registers from

1,418,499

in

1261 to

1,967,898

in 1274.

IO

3 He then imposed higher taxes on merchants,

instituted state monopolies of

new

products, and forbade the private produc-

tion of certain commodities. In short, Ahmad's policies were lucrative for the

state treasury. Yet the Chinese sources accuse him of profiteering and

cronyism. They assert that he capitalized on the new taxes and monopolies to

enrich

himself.

Moreover, they denounce him for appointing Muslims to

prominent positions and for attempting to place his own inexperienced and

perhaps unqualified sons in influential posts in the bureaucracy. Viewed from

a different perspective, however, the Chinese accusations appear less serious.

Bringing like-minded associates and relatives into government was perfectly

sensible. If Ahmad were to overcome opposition and implement his policies,

he needed to place his supporters in influential positions. He did impose

heavy taxes and high prices, but his position at court

—

not to mention

possible promotions and rewards

—

depended on his ability to satisfy the

Mongols' revenue requirements. He was a dedicated and effective agent of

the Mongolian court, which had

a

considerable and pressing need for income.

Ahmad's policies, however, aroused the opposition of some leading Chi-

nese at court. Khubilai's Confucian advisers resented Ahmad's power and

accused him of profiteering and of having a "sycophantic character and

treacherous designs." By the late 1270s, the heir apparent Chen-chin had

joined the opposition. Chen-chin objected to the prominent positions ac-

corded to Ahmad's sons and relatives. On 10 April 1282, while Khubilai was

in his secondary capital at Shang-tu, a cabal of Chinese conspirators lured

Ahmad out of his house and assassinated him.

10

* Within a few days,

Khubilai returned to the capital and executed the conspirators. But his

Chinese advisers eventually persuaded him of Ahmad's treachery and corrup-

tion. The evidence they used against Ahmad was suspect, but Khubilai was

convinced of the Muslim minister's guilt and so had his corpse exhumed and

hung in a bazaar; then he allowed his dogs to attack it.

Yet the elimination of Ahmad did not resolve Khubilai's financial prob-

lems.

His revenue requirements became even more pressing after Ahmad's

death because he initiated several military expeditions

to

Japan and Southeast

Asia. Simultaneously, by the early 1280s, Khubilai had lost some of his most

faithful Chinese advisers, including Hsu Heng, Yao Shu, and Wang O, all of

whom had died by that time. Their deaths offered non-Chinese counselors

103 See ibid., p. 232.

104 See Moule, Quinsai, pp. 79—88, for an account of this cabal and its plot to kill Ahmad.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC PROBLEMS IN LATER YEARS 475

greater opportunities to influence him. Khubilai's own infirmities com-

pounded these troubles and may, in part, have accounted for his abdicating

more and more of his responsibilities as a ruler.

The Chinese sources accuse Lu Shih-jung, another of the so-called villain-

ous ministers, of capitalizing on Khubilai's difficulties to increase his own

power. After Ahmad's death, Lu became the head of the Ministry of the Left

in the Central Secretariat, with jurisdiction over much of the financial admin-

istration in China. Like Ahmad, he attempted to increase the government's

revenues in order to meet the mounting costs at court. He sought to augment

the government's income from monopolies, to impose higher taxes on foreign

trade, to issue more paper money (an easier way to pay government debts),

and to staff the tax offices with merchants.

10

' Lu's economic programs engen-

dered the same hostility as did those of Ahmad, his predecessor as financial

administrator. The Chinese accused him of profiteering, cronyism, and ex-

ploitation of his own people and of persecuting, hounding, and even execut-

ing rivals and enemies. The accuracy of many of these charges is subject to

doubt because the sources do not reflect Lu's own version of events. Like

Ahmad, Lu simply attempted to raise desperately needed revenues, but his

efforts earned the enmity of many of his fellow Chinese. Again, Crown Prince

Chen-chin led the opposition to Lu, who was arrested by May 1285 and

executed by the end of the year. His death may have removed a man that the

Chinese perceived to be an exploiter, but it did not alleviate the fiscal

problems faced by the court.

Aside from fiscal problems, Khubilai also faced difficulties in achieving

the economic integration of the Southern Sung into his realm. A truly

unified and centralized China was essential if Khubilai wished to fulfill any

other economic or political objectives. Khubilai first sought to ingratiate

himself with the Chinese in the south by releasing many of the soldiers and

civilians whom his armies had captured. Then he issued edicts aimed at the

economic recovery of south China, including prohibiting Mongols from

ravaging the farmlands and establishing granaries to store surplus grain and

to ensure sufficient supplies in times of agricultural distress. The court did

not generally confiscate land from the large estates of the southern landown-

ers.

Nor did it undermine their power; it simply added another layer

—

the

Mongolian rulers

—

at the top of the hierarchy. The land taxes it imposed

were not onerous and, in times of distress, were waived. Salt, tea, liquor and

other commodities were monopolized, but the resulting prices were not

burdensome. Khubilai encouraged maritime commerce, one of the bases of

105 Herbert Franke, Geld und Wirtichaft in China unter der Mongolenbemcbaft: Beilrage zur Wirucbaftige-

schichte

der Yiian-Zeit (Leipzig, 1949), pp- 72—4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

476 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

the south's prosperity. Self-interest surely was a motivating factor in these

policies, for the economic recovery of the south would eventually mean

greater profits.

Despite his efforts, the hostile feelings of some Chinese in the south did

not subside, hampering Khubilai's economic program. There were several

uprisings against Mongolian rule. In 1281, Khubilai's troops crushed the

first of these, which was led by Ch'en Kuei-lung, by beheading - if

we

trust

the Chinese historians - twenty thousand of the rebel soldiers. One hundred

thousand Mongolian troops were required to overwhelm a more serious rebel-

lion in Fukien. Other insurrections continued until the end of the reign.

Most of those who resisted the Mongols, however, did not resort to such

violent means. A few refused to serve the Mongols, feeling that the "barbari-

ans"

were not interested in Chinese civilization and thought. Others founded

special academies to pursue their own intellectual interests while simply

avoiding involvement with the Mongols. Such opposition deprived Khubilai

and the Yuan court of badly needed expertise while the continuing turbu-

lence compelled them to station troops in the south, at great expense. In

sum, the south was not totally integrated by the end of Khubilai's reign, and

the economic problems, together with political disruptions, continued to

plague the Yuan court in this region.

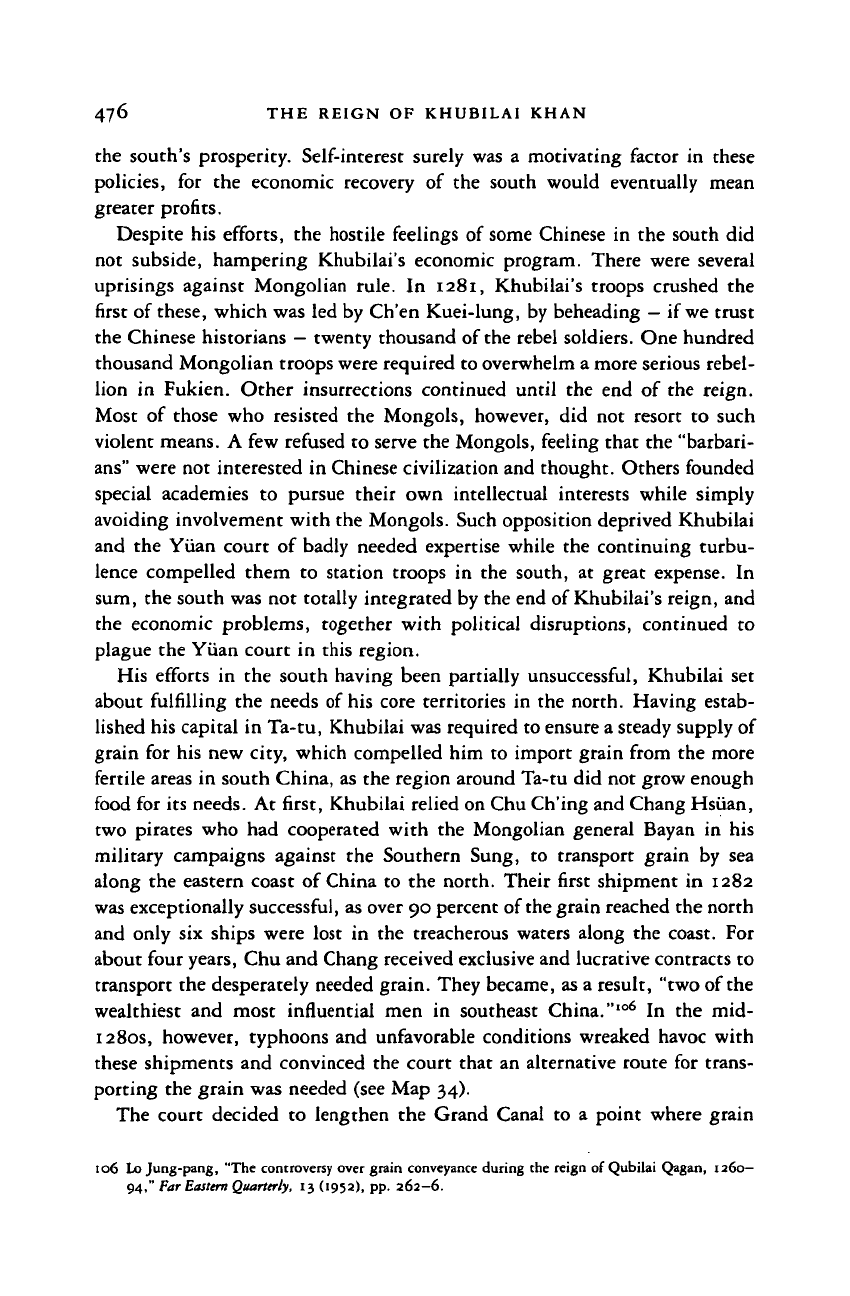

His efforts in the south having been partially unsuccessful, Khubilai set

about fulfilling the needs of his core territories in the north. Having estab-

lished his capital in Ta-tu, Khubilai was required to ensure a steady supply of

grain for his new city, which compelled him to import grain from the more

fertile areas in south China, as the region around Ta-tu did not grow enough

food for its needs. At first, Khubilai relied on Chu Ch'ing and Chang Hsiian,

two pirates who had cooperated with the Mongolian general Bayan in his

military campaigns against the Southern Sung, to transport grain by sea

along the eastern coast of China to the north. Their first shipment in 1282

was exceptionally successful, as over 90 percent of

the

grain reached the north

and only six ships were lost in the treacherous waters along the coast. For

about four years, Chu and Chang received exclusive and lucrative contracts to

transport the desperately needed grain. They became, as a result, "two of the

wealthiest and most influential men in southeast China."

106

In the mid-

12808,

however, typhoons and unfavorable conditions wreaked havoc with

these shipments and convinced the court that an alternative route for trans-

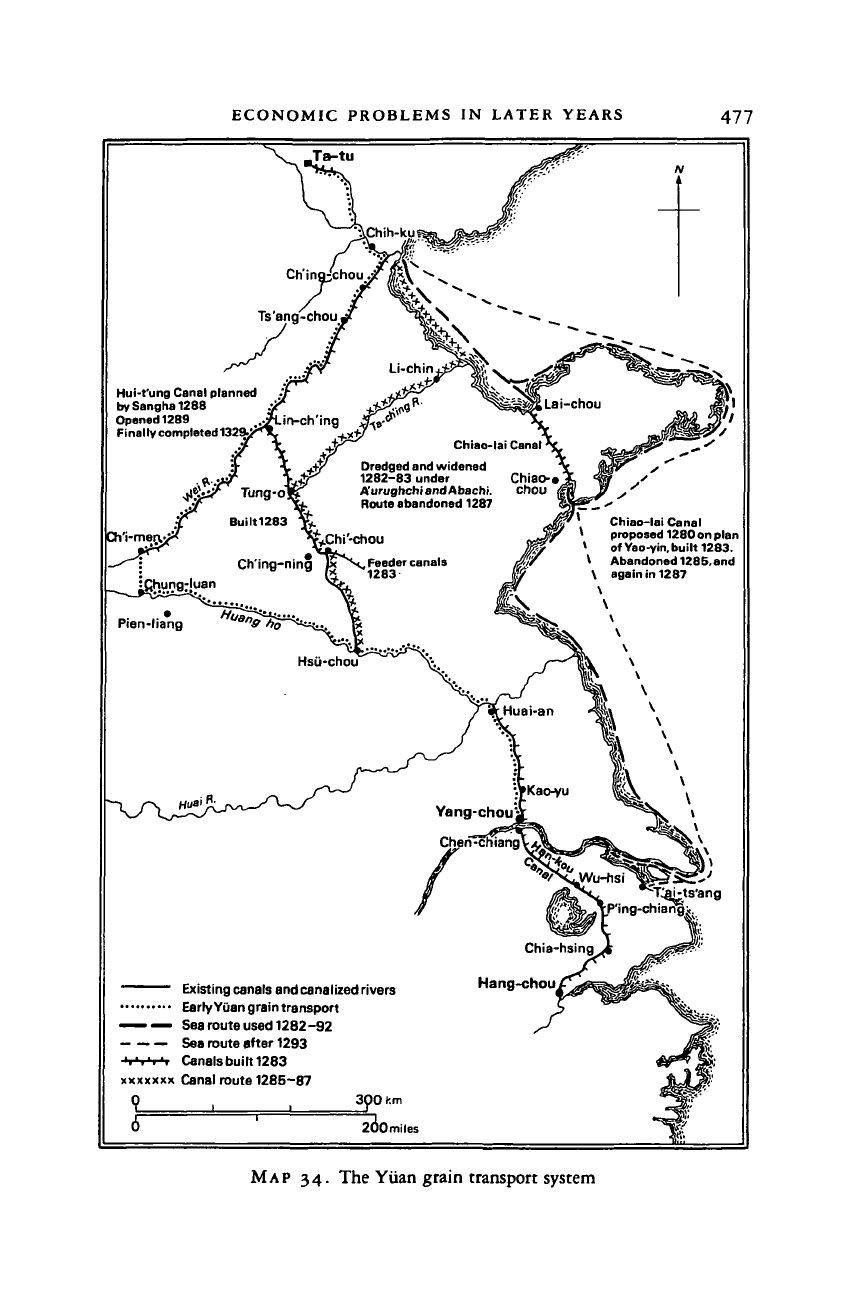

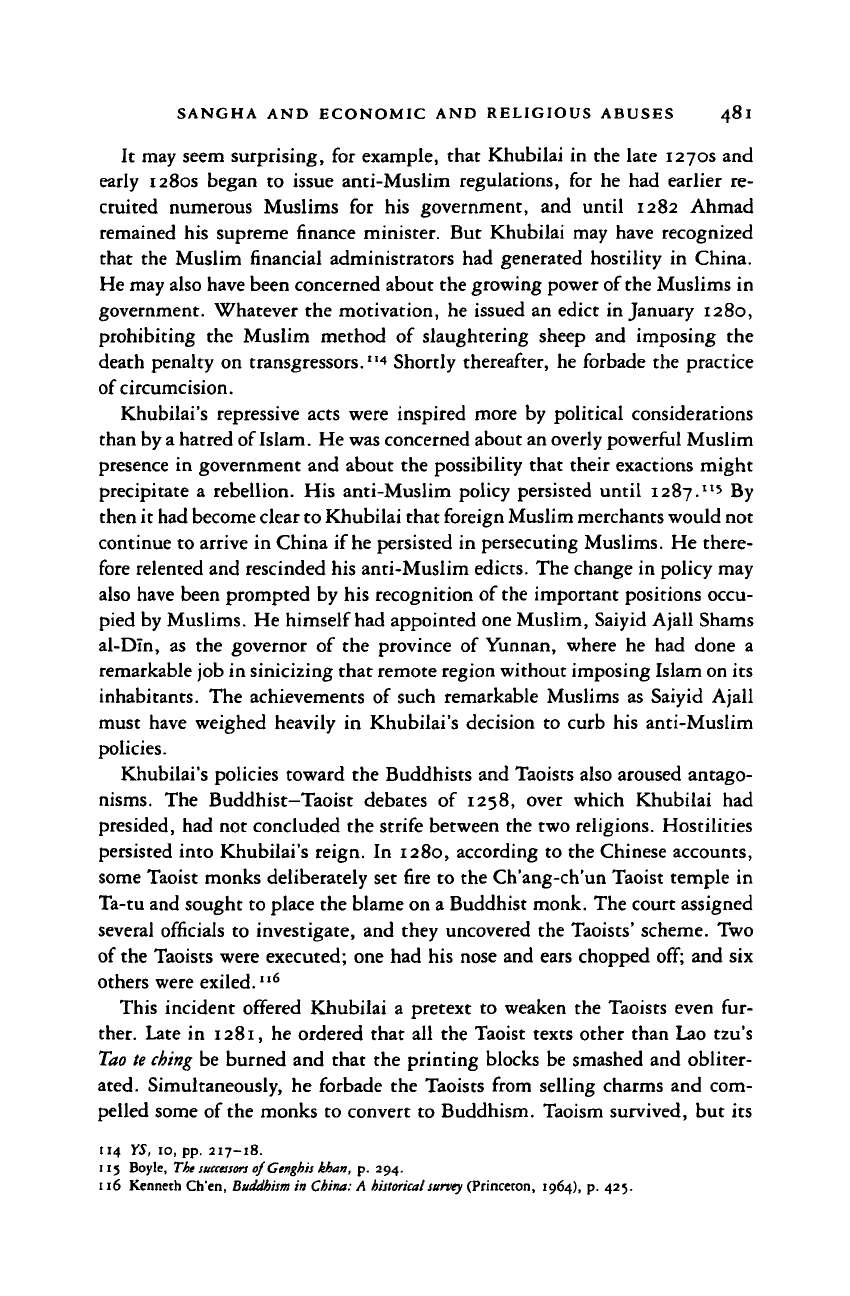

porting the grain was needed (see Map 34).

The court decided to lengthen the Grand Canal to a point where grain

106 Lo Jung-pang, "The controversy over grain conveyance during the reign of Qubilai Qagan, 1260—

94,"

Far

Eastern

Quarterly, 13 (1952), pp. 262—6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ECONOMIC PROBLEMS

IN

LATER YEARS

477

Hui-t'ung Canal planned

bySangha1288

Opened 1289 jTLin-ch'ing

Finallvcompleted1329

J

}

>

*% ±#i

Ch'ingjchou

Ts'ang-chou

Dredged and widened

1282-83 under Chiao-e

A'urughchiandAbachi. chou

Route abandoned 1287

*

proposed 1280

on

plan

of

Yao-yin.

built 1283.

Abandoned

1285.

and

\

again in 1287

\

Feeder canals

1283

Yang-chou

Chen-Chiang

^^

Wu-hsi

ing-chiarigj

Chia-hsing

Hang-chou

Existing canals

and

canalized rivers

Earh/YQan grain

transport

——

^

Sea

route

used

1282-92

Sea route after 1293

'I'I'I'I

Canals

built

1283

xxxxxxx Canal route 1285-87

0 300 kn

200miles

MAP

34.

The Yiian grain transport system

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

478 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

shipments could easily reach Ta-tu. This project entailed the construction of

a 135-mile-long canal from Ch'ing-ning to Lin-ch'ing in Shantung Province;

from Lin-ch'ing, goods could be transshipped on the Wei River to Chih-ku, a

short distance from Ta-tu. Grain could thus be transported from the Yangtze

directly

to

Khubilai's capital. By February 1289, the extension was com-

pleted, and the new canal, known as the Hui-t'ung, was opened

to

boat

traffic.

IO

? The expenses entailed in the extension of the canal were enormous.

About three million laborers took part

in

its construction, for which the

government expended vast sums of

money.

Maintenance was also costly, and

the huge expenditures necessitated by the canal no doubt contributed materi-

ally to the fiscal problems plaguing the Mongolian court in the late 1280s.

THE REGIME OF SANGHA AND ECONOMIC

AND RELIGIOUS ABUSES

Sangha was the last

of

the triumvirate

of

"villainous ministers" who at-

tempted to deal with the court's fiscal problems under Khubilai. Like Ah-

mad, he was not Chinese, but his ethnic origins are obscure. Historians had

assumed that he was.an Uighur, but recent studies suggest that he was

a

Tibetan.

He

first came into prominence as

a

member

of

the staff of the

Buddhist 'Phags-pa lama. Khubilai was impressed with Sangha's capabilities

and resourcefulness, and sometime before 1275 he appointed the young

Buddhist as head of the Tsung-chih yuan, the office in charge of Tibetan and

Buddhist affairs. Here, too, Sangha proved extremely successful, particularly

in crushing a revolt in Tibet in 1280 and subsequently stationing garrisons,

establishing an effective postal system, and pacifying the various Buddhist

sects in the region. After the murder of Ahmad in 1282 and the execution of

Lu Shih-jung

in

1285, Sangha became the dominant figure in the govern-

ment. As such, he attracted the same kinds of criticism that his predecessors

had. He eventually was accused of corruption, theft of Khubilai's and the

state's property, and disgusting carnal desires. Some of the most prominent

men of the 1280s, including the renowned painter and official Chao Meng-

fu, opposed him and warned Khubilai of

his

nefarious intentions.

108

It seems

clear, however, that Khubilai prized Sangha's talents, for he continued

to

promote the Buddhist, naming him the minister of the right in December

1287.

107 YS, 15, p. 319.

108 Herbert Franke, "Sen-ge: Das Leben eines uigurischen Staatsbeamten zur Zeit Chubilai's dargestellt

nach Kapitel 205 der Yiian-Annalen," Sinica, 17 (1942), pp. 90-100. Luciano Petech, "Sang-ko,

a

Tibetan statesman in Yuan China," Ada Orientalia Academiat

Scientiarum

Hungaricae,

34 (1980), pp.

193—208.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SANGHA AND ECONOMIC AND RELIGIOUS ABUSES 479

Which of Sangha's policies attracted the hostility of Chinese officials? One

was his active support for foreigners in China. He served as a patron for

Uighur scholars and painters; he persuaded Khubilai to halt a government-

sponsored campaign against Muslims; and he sponsored the founding of the

National College for the Study of the Muslim Script in 1289. His role as

protector of the foreigners did not endear him to the Chinese. Sangha's

financial policies also drew hostile reactions. He introduced a higher tax on

commerce and increased the price of salt, tea, and liquor. More onerous was

his reform of the paper currency, which was threatened by a potentially

devastating inflation. In April 1287, Sangha replaced the old notes with a

new unit known as Chih-yuan ch'ao, which was named after Khubilai's reign

title of Chih-yuan. The old currency would be exchanged on a five-to-one

basis for the Chih-yuan notes. Those Chinese who were forced to exchange

their less valuable old notes at less-than-satisfactory rates were thus incensed

by the decline in their net worth.

Sangha's reputation among the Chinese was particularly damaged by his

apparent involvement with and support of a Buddhist monk named Yang

Lien-chen-chia. Yang, who came from China's western regions and may have

been a Tibetan or possibly a Tangut, had been appointed as the supervisor of

Buddhist teachings in south China {Chiang-nan tsung-she chang shih-chiao),

almost as soon as the Southern Sung had been toppled.

IO

9

In this office, he

served under the jurisdiction of Sangha, who was in charge of Buddhist

affairs for all of China. Yang constructed, restored, and renovated numerous

temples and monasteries in south China, but he also converted some Confu-

cian and Taoist temples into Buddhist ones. Such conversions generated great

hostility among the Chinese.

Even more upsetting to the Chinese were the methods that Yang used to

raise funds for the construction and repair of the temples and monasteries. In

1285,

he broke open the tombs of the Sung royal family and ransacked the

valuables buried with emperors and empresses. He plundered 101 tombs and

removed 1,700 ounces of gold, 6,800 ounces of silver, 111 jade vessels, 9

jade belts, 152 miscellaneous shells, and 50 ounces of pearls.'

10

Yang used

these precious goods to pay for the erection and restoration of the Buddhist

temples, and he also converted some of the palace buildings into Buddhist

temples. To make matters worse, he employed forced laborers to rebuild and

convert these temples and expropriated land from the big landowners to

109 On Yang Lien-chen-chia, see Herbert Franke, "Tibetans in Yuan China," in

China under Mongol

rule,

ed. John D. Langiois, Jr. (Princeton, 1981), pp.

32—5.

no T'ao Hsi-sheng, "Yuan tai Mi-le pai lien chiao hui te pao tung," Shih

huoyueh

k'an, 1 (1933), pp.

132-3;

Yen Chien-pi, "Nan Sung liu ling i shih cheng ming chi chu ts'uan kung h hui nien tai

k'ao,"

Yen-ching hsiieh

pao,

30(1946), pp. 28—36.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

480 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

provide revenues for their maintenance. The southern landowners were infuri-

ated by the high-handed expropriation of their lands and by the tax exemp-

tions granted

to

the temples. The landowners also began

to

accuse Yang of

profiteering, corruption, and womanizing.

A more serious transgression of which Yang was accused was the desecra-

tion

of

the corpses

of

the Sung royal family. The body

of

one

of

the last

emperors

was

said

to

have been exhumed, hung from

a

tree,

and

then

burned, and as

a

final indignity the bones were reburied amidst the bones of

horses and cows.

111

Yang was blamed for this outrage, but official historians

are

so

violently hostile

to

him that

it is

difficult

to

determine how much

credence should be given to this account. Why would Yang deliberately and

needlessly provoke

the

wrath

of

the southern Chinese by acts that violated

and grated on Chinese sensibilities? Such a gratuitous deed hardly makes any

sense

and is

scarcely credible. Yang's positive accomplishments

can be

gleaned only through inference.

He

was

a

devout Buddhist who tried

to

promote the interests

of

his religion, and Buddhism did indeed flourish

in

the south during his era. By 1291, there were 213,148 Buddhist monks and

42,318 temples

and

monasteries

in

the country, due partly

at

least

to his

patronage.

112

Yet Yang's abuses rankled the southern Chinese and reflected on his patron

Sangha. Both were, from

the

standpoint

of

the Chinese, exploitative and

oppressive. The Chinese officials reviled them for their financial and personal

misdeeds,

and

finally these accusations compelled action.

On 16

March

1291,

Khubilai relieved Sangha of his responsibilities and placed him under

arrest. By August, the decision had been made to execute him.

11

* The last of

the three villainous ministers now was dead,

yet the

three men's actions

reflected

on

Khubilai,

as

the ruler who had appointed them. One minister

after another had taken charge, and each had become for

a

while the virtual

ruler

of

the country. Within

a

few years, however, each

in

turn was chal-

lenged, accused

of

serious crimes,

and

eventually either executed

or

mur-

dered. Many lower officials doubtless wondered whether there was a guiding

figure in China. Was Khubilai really in charge of

his

realm, and was he aware

of the empire's affairs and

of

his subordinates' actions?

He

had begun

to

pursue policies that were on occasion diametrically opposed

to

those he had

earlier upheld. The religious toleration that had been

a

cornerstone

of

his

policies and had been vital

to

the Mongols' success appeared

to

have been

abandoned. Problems with the religions of China intensified.

111 Paul Demieville, "Notes d'archeologie chinoise," Bulletin

de

I'Ecole

Frangaise

d'Extrem-Orimt,

25

(1925),

pp. 458—67; repr.

in

h\%Cboixd

l

itudaiinologiquti(ig2i—1970) (Leiden, 1973), pp. 17—26.

112 Ratchnevsky, "Die mongolische Grosskhan und die buddhistische Kirche,"

p. 497.

113

YS,

16, p. 344.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

SANGHA AND ECONOMIC AND RELIGIOUS ABUSES 481

It may seem surprising, for example, that Khubilai in the late 1270s and

early 1280s began to issue anti-Muslim regulations, for he had earlier re-

cruited numerous Muslims for his government, and until 1282 Ahmad

remained his supreme finance minister. But Khubilai may have recognized

that the Muslim financial administrators had generated hostility in China.

He may also have been concerned about the growing power of

the

Muslims in

government. Whatever the motivation, he issued an edict in January 1280,

prohibiting the Muslim method of slaughtering sheep and imposing the

death penalty on transgressors."

4

Shortly thereafter, he forbade the practice

of circumcision.

Khubilai's repressive acts were inspired more by political considerations

than by

a

hatred of Islam. He was concerned about an overly powerful Muslim

presence in government and about the possibility that their exactions might

precipitate a rebellion. His anti-Muslim policy persisted until 1287."

5

By

then it had become clear to Khubilai that foreign Muslim merchants would not

continue to arrive in China if

he

persisted in persecuting Muslims. He there-

fore relented and rescinded his anti-Muslim edicts. The change in policy may

also have been prompted by his recognition of the important positions occu-

pied by Muslims. He himself had appointed one Muslim, Saiyid Ajall Shams

al-DIn, as the governor of the province of Yunnan, where he had done a

remarkable job in sinicizing that remote region without imposing Islam on its

inhabitants. The achievements of such remarkable Muslims as Saiyid Ajall

must have weighed heavily in Khubilai's decision to curb his anti-Muslim

policies.

Khubilai's policies toward the Buddhists and Taoists also aroused antago-

nisms. The Buddhist—Taoist debates of 1258, over which Khubilai had

presided, had not concluded the strife between the two religions. Hostilities

persisted into Khubilai's reign. In 1280, according to the Chinese accounts,

some Taoist monks deliberately set fire to the Ch'ang-ch'un Taoist temple in

Ta-tu and sought to place the blame on a Buddhist monk. The court assigned

several officials to investigate, and they uncovered the Taoists' scheme. Two

of the Taoists were executed; one had his nose and ears chopped off; and six

others were exiled."

6

This incident offered Khubilai a pretext to weaken the Taoists even fur-

ther. Late in 1281, he ordered that all the Taoist texts other than Lao tzu's

Tao te ching

be burned and that the printing blocks be smashed and obliter-

ated. Simultaneously, he forbade the Taoists from selling charms and com-

pelled some of the monks to convert to Buddhism. Taoism survived, but its

114 YS, io, pp.

217—18.

115 Boyle, The

successors

of

Genghis

khati, p. 294.

116 Kenneth Ch'en, Buddhism in China: A historical

survey

(Princeton, 1964), p. 425.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

482 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

political and economic influence was undercut. The Buddhists, who had

gained a smashing victory, gloated over the defeat of their religious rivals and

became increasingly assertive. Throughout the 1280s, the Buddhists ac-

quired more and more wealth, land, and authority, and the sources are

replete with the accounts of abuses by such Buddhists as Sangha and Yang

Lien-chen-chia. These Buddhists began to alienate the Chinese, and the

Mongols, as foreigners, were also tarnished by their deference toward and

support of the Buddhists, particularly those from Tibet and other regions

outside of China.

DISASTROUS FOREIGN EXPEDITIONS

Khubilai's difficulties within China presaged similar catastrophes abroad. A

lack of control characterized both domestic and foreign policies. The bal-

anced executive authority that Khubilai had exercised seems to have been

dissipated. Ill-considered decisions tended to be the rule rather than the

exception. As both the emperor of China and the khan of khans, Khubilai

encountered relentless pressure to prove his worth, virtue, and acumen by

incorporating additional territory into his domains. He thus initiated several

ill-conceived and foolhardy foreign ventures.

The second invasion of Japan

The most prominent such venture was the new expedition

to

Japan.

After the

failure of the first expedition in 1274 and repeated rebuffs by the Japanese

shogun of Khubilai's invitations to send tribute embassies to China, Khubilai

prepared to launch another invasion of Japan. Seven years elapsed, however,

before he could actually dispatch an expedition; only after the pacification of

the Southern Sung could he once again turn his attention to Japan.

Khubilai chose a multiethnic leadership for the campaign - a Korean as

the admiral, Fan Wen-hu as the Chinese general, and Hsin-tu as the Mongo-

lian general. He provided his generals with a massive invasion force: 100,000

troops, 15,000 Korean sailors, and 900 boats."

7

The Yuan military command planned a two-pronged assault on the Japa-

nese islands (see Map 35). Forty thousand troops from north China, trans-

ported in Korean ships, were to link up on the island of Iki with forces

departing from Ch'iian-chou in Fukien and would then jointly attack the rest

of Japan. The soldiers from the north, however, set forth alone in the spring

of 1281 because the larger southern force had encountered delays. By June,

117 YS, 11, pp. 226, 228.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008