The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 06. Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

KHUBILAI AND CHINA 42 I

Buddhist owners."* He did not proscribe Taoism but merely curbed what he

believed to be Taoist excesses. A vindictive purge would have enraged the

Taoists, and their many sympathizers would have impeded the Mongols'

efforts to govern north China. Khubilai's decision, as well as his moderation

in punishing the Taoists, appears to have met with the approval of his

Chinese subjects.

Having acquitted himself with distinction at the debate, Khubilai re-

ceived a new assignment. Toward the end of 1258, Mongke devised a plan for

the conquest of southern China. He would deploy his forces along four

fronts,

with the troops under his own personal command first seeking to

occupy Szechwan and then marching eastward. Khubilai would then lead his

detachment from K'ai-p'ing and cross the Yangtze River at O-chou on the

central Yangtze, where he would engage the Sung forces. The other detach-

ments would move from Yunnan and from the Liu-p'an shan area in Shensi

toward the Sung stronghold at Hsiang-yang. The Mongols clearly hoped for a

quick victory in the west that would induce the Sung to capitulate. But

Mongke's own campaign did not fulfill his expectations, for he encountered

stiff resistance from the Sung forces. After taking Ch'eng-tu in March 1258,

his expedition was bogged down vainly attempting to take the strongly

defended city of Ho-chou (modern Ho-ch'uan county, Szechwan) throughout

the last half of 1258 and the first seven months of 1259. Then on 11 August,

Mongke died while on campaign in the vicinity of Ho-chou.

The Mongolian campaigns throughout Eurasia came to a standstill after

Mongke's death. His own troops did not make any further advances and did

not link up with the three other divisions attacking the Sung. In the Middle

East, Mongke's younger brother Hiilegii, who had expanded the lands under

Mongol control in the west, hastily headed back toward the Mongolian

homeland, leaving only a small detachment to guard his newly conquered

domains. This disruption in the Mongolian world was due to the lack of an

orderly succession to the khaghanate. The leader with the greatest military

power often emerged victorious.

The struggle for the throne in 1259 was conducted within the house of

Tolui. It was more than a struggle between two men, for it reflected a major

division within the Mongolian elite. Khubilai, who was attracted by the

civilizations he had helped conquer and who sought advice and aid from the

subject populace, represented the Mongols, who were influenced by and tried

for an accommodation with the sedentary world. His younger brother Arigh

Boke emerged as the defender of traditional Mongolian ways and values. The

14 Edouard Chavannes, "Inscriptions ec pieces de chancellerie chinoises de l'lpoque mongole," Voting

Poo,

9 (1908), pp. 381-4.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

422 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

world of the steppe was, to him, more attractive than was the world of the

sown. He mistrusted his older brothers Hiilegii and Khubilai and considered

them to be tainted by foreign values and attitudes. The stage was thus set for

a fraternal combat concerning the future direction of the Mongolian empire.

Yet the struggle was delayed for a few months. In mid-September 1259,

Khubilai learned of Mongke's death from a messenger dispatched by his

half-

brother, who requested that he return to the Mongolian homeland for the

election of

the

new khaghan. Khubilai had just reached the northern banks of

the Yangtze River and was preparing for an invasion of the south. According

to the Yuan

shih,

he told the messenger, "I have received imperial orders to

come south. How can I return without having achieved merit?"

1

' The Persian

historian Rashid al-Din substantiates this account, noting that Khubilai

responded, "We have come hither with an army like ants or locusts: How can

we turn back, our task undone, because of rumors?"

16

It seems likely that

Khubilai wanted to triumph over the Sung in order to improve his chances in

the struggle for the khaghanate. He would enter the contest as a successful

military leader. Thus he did not return to the north immediately.

KHUBILAI VERSUS ARIGH BOKE

Khubilai's troops persisted in their campaign against the Southern Sung

through the winter of 1259. They first crossed the Yangtze and then laid

siege to the heavily fortified town of O-chou. A victory here would have

bolstered Khubilai's prestige in the Mongolian world, but the Sung defend-

ers of the town were determined not to surrender. The Southern Sung chancel-

lor

(cb'eng-hsiang)

Chia Ssu-tao was, however, willing to compromise. He

dispatched an envoy to offer Khubilai an annual payment of silver and textiles

in return for a pledge to maintain the Yangtze as their common border.

Khubilai's Confucian adviser Chao Pi commented, "Now, after we have

already crossed the Yangtze, what use are these words?"'

7

Khubilai was

intent on victory.

The succession crisis saved the Sung. Arigh Boke mobilized his troops

right after Mongke's death and began to create alliances with influential

Mongolian nobles. Early in 1260, one of his allies marched toward Khubi-

lai's town of K'ai-p'ing. Chabi, who had stayed behind while her husband

was on campaign, immediately sent an envoy to inform Khubilai of his

younger brother's plans and actions. Khubilai would have to abandon the

15 YS, 4, p. 61.

16 Boyle, The

successors

of Genghis khan, p. 248.

17 Herbert Franke, "Chia Ssu-tao (1213—1275): A 'bad last minister,' " in

Confucian

personalities,

ed.

Arthur F. Wright and Denis C. Twitchett (Stanford,

Calif.,

1962), p. 227.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

KHUBILAI AND ARIGH BOKE 423

siege of O-chou and depart for the north to counter Arigh Boke. He with-

drew most of his troops from O-chou, leaving only a token force to preserve

the territorial gains he had made.

18

Capitalizing on Khubilai's sudden with-

drawal, Chia Ssu-tao authorized an attack on the small detachment of Mongo-

lian troops, quickly defeating them and reoccupying the Sung territories.

Chia deliberately portrayed this minor engagement

as a

great victory, mislead-

ing the Sung court and contributing to its resolve to reject any compromise

with the Mongols.

Meanwhile Khubilai marched toward and reached K'ai-p'ing in the spring

of 1260. The Yuan

shih

reveals that numerous princes "begged" Khubilai to

take the throne. After three ceremonial "refusals," he acceded to their wishes,

and on 5 May a hastily convened khuriltai elected him as the great khan.

Because much of the Mongolian nobility did not attend the meeting,

Khubilai's election could be and was challenged. Within a month, for exam-

ple,

Arigh Boke was proclaimed as the rival great khan in the old Mongolian

capital of Khara Khorum. Arigh Boke could count on the support of two of

the three remaining principal khanates, the Golden Horde of Russia and the

Chaghadai khanate of Central Asia. Khubilai's only supporter was his brother

Hiilegii, who himself faced serious threats to his authority in the Middle

East. While en route back to Mongolia, Hiilegii had learned that the

Mamluk rulers of Egypt had defeated his forces at 'Ain Jalut (in Syria) in

September

1260.

•»

Moreover, the Golden Horde, seeking to dislodge

Hiilegii from Azerbaijan along the Russian-Persian border, had declared war

on him. Hiilegii's attention was thus diverted elsewhere, and so he could be

of little help to Khubilai in the struggle for succession.

Khubilai was compelled to rely on the resources of China and on his

Chinese subjects for support. He issued a proclamation, which was actually

composed by his Confucian adviser Wang O,

20

admitting that Mongolian

military skills were insufficient to rule China. A sage who cultivated good-

ness and love and who governed in accordance with the traditions of the

ancestors was needed to unite the Chinese, and he implied that he was just

the man. He also advocated a reduction of

the

tax and corvee burdens on the

people." A few days after issuing this proclamation Khubilai adopted the

Chinese reign title

chung-t'ung

(literally, "moderate rule"),

22

although he did

so without adopting a Chinese name for his dynasty. The governmental

18 YS, 4, pp. 62-3.

19 Bernard Lewis, "Egypt and Syria," in vol. iA ofThe

Cambridge history

of

Islam,

ed. P. M. Holt, Ann K.

S. Lambton, and Bernard Lewis (Cambridge, 1970), pp. 212-13.

20 See Chan Hok-Ham, "Wang O (1190—1273),"

Papers

on far

Eastern

History, 12 (1975), pp. 43—70.

21 For the text of the proclamation, see YS, 4, pp. 64—5.

22 Also interpreted as "pivotal succession." See Morris Rossabi, Khubilai Khan: His life and

times

(Berkeley

and Los Angeles, 1988), p. 243, n. 12.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

424 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

institutions that he developed, the Chung-shu sheng (Central Secretariat)

and the Hsiian-wei ssu (Pacification commissions), resembled the traditional

Chinese ones. Khubilai, in effect, wished to signal to all the Chinese that he

intended to adopt the trappings and style of a typical Chinese ruler. The

Southern Sung Chinese, however, were not receptive to such concessions.

They detained Hao Ching, the envoy sent by Khubilai to negotiate a diplo-

matic settlement of their conflict. Hao remained a prisoner at the Sung court

from 1260 until the successful launching of Khubilai's military campaigns

against the southern Chinese in the 1270s.

Khubilai himself was able to use the resources of north China but sought

to deny supplies from the sedentary world to Arigh Boke. Based in Khara

Khorum, Arigh Boke needed to import most of

his

provisions, and Khubilai

was determined to sever his younger brother's supply lines. Kansu and

northwest China were controlled by one of Khubilai's allies, as were the

Uighur lands farther west. Arigh Boke's principal source of support was the

Chaghadai khan Alghu, who was based in Central Asia. Alghu at first helped

Arigh Boke in his efforts to seize the throne, but disputes over their individ-

ual shares of tax revenues and spoils finally drove them apart. After 1262,

therefore, Arigh Boke had no dependable allies and no reliable source of

supplies. It was only a matter of time before he would have to abandon his

struggle for the throne. After several skirmishes, in 1263 he surrendered to

Khubilai. Conveniently enough for Khubilai, he died within a few years

while still in captivity, giving rise to speculation that he had been poisoned.

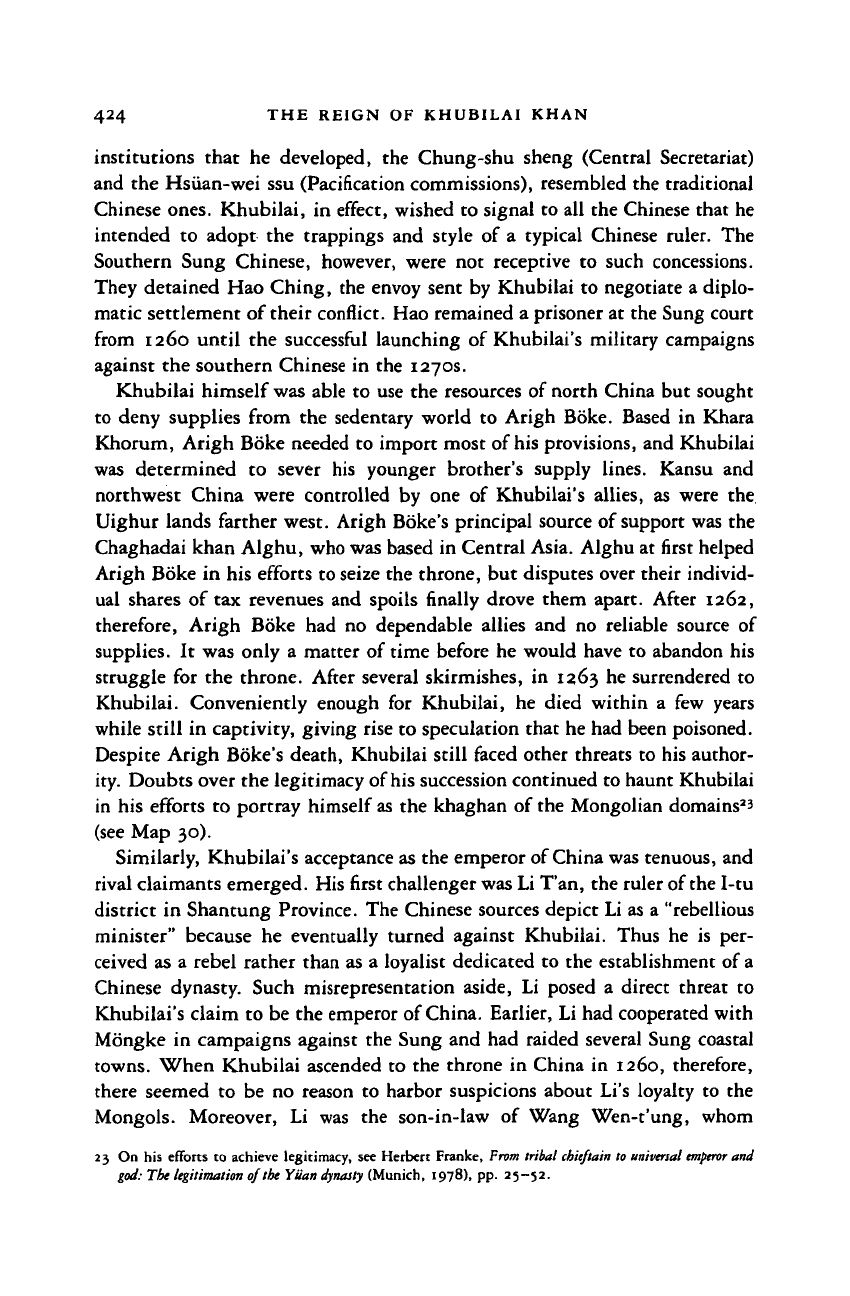

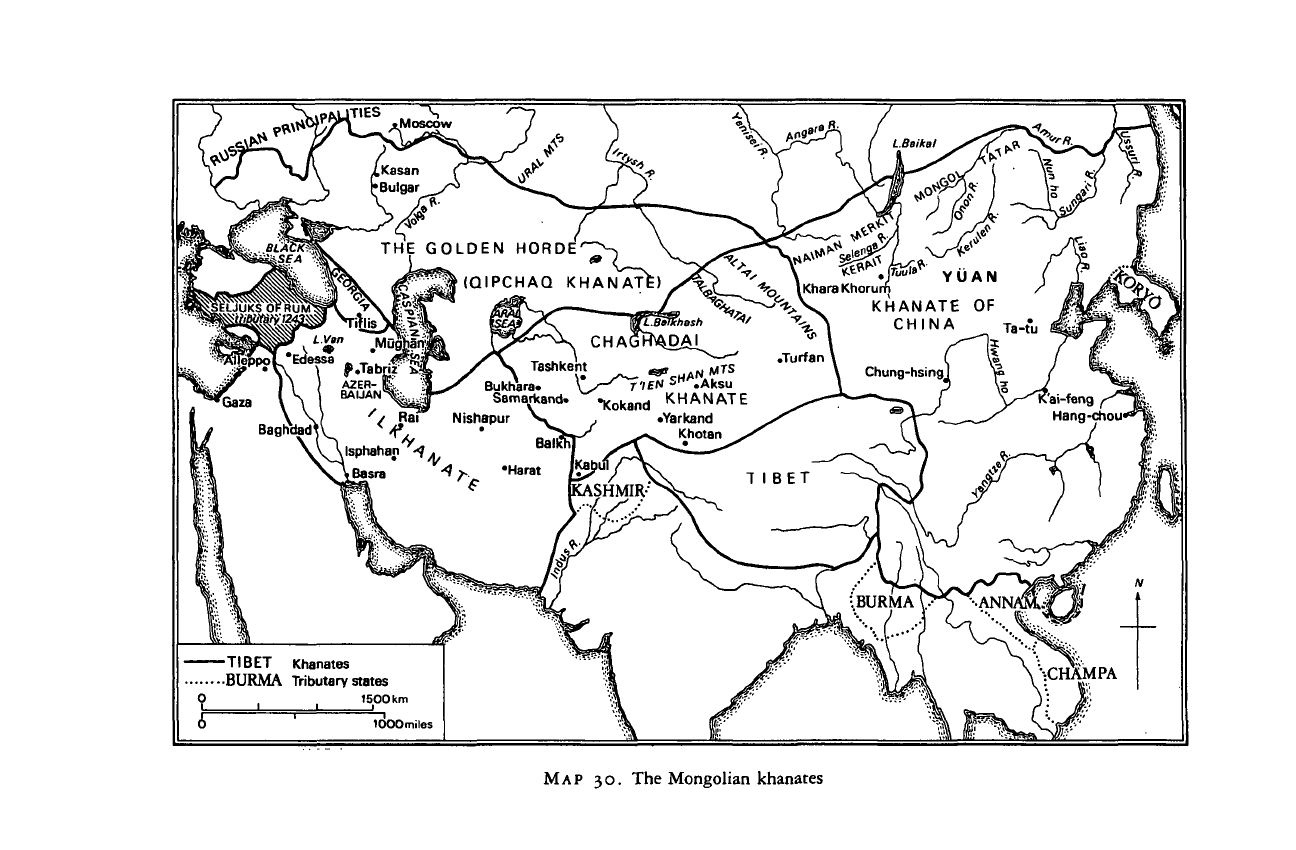

Despite Arigh Boke's death, Khubilai still faced other threats to his author-

ity. Doubts over the legitimacy of his succession continued to haunt Khubilai

in his efforts to portray himself

as

the khaghan of the Mongolian domains

23

(see Map 30).

Similarly, Khubilai's acceptance as the emperor of China was tenuous, and

rival claimants emerged. His first challenger was Li T'an, the ruler of

the

I-tu

district in Shantung Province. The Chinese sources depict Li as a "rebellious

minister" because he eventually turned against Khubilai. Thus he is per-

ceived as a rebel rather than as a loyalist dedicated to the establishment of

a

Chinese dynasty. Such misrepresentation aside, Li posed a direct threat to

Khubilai's claim to be the emperor of

China.

Earlier, Li had cooperated with

Mongke in campaigns against the Sung and had raided several Sung coastal

towns. When Khubilai ascended to the throne in China in 1260, therefore,

there seemed to be no reason to harbor suspicions about Li's loyalty to the

Mongols. Moreover, Li was the son-in-law of Wang Wen-t'ung, whom

23 On his efforts to achieve legitimacy, see Herbert Franke, From tribal chieftain to

universal emperor

and

god: The legitimation of the Yiian dynasty (Munich, 1978), pp. 25-52.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE GOLDEN HORD

(QIPCHAQ KHANAT

Tashkent

Bukhara.

Samarkand.

"

Vokand

KHANATE

Nishapur

v^ ,

.Yarkand

Khotan

TIBET Khanates

BURMA Tributary states

1500 km

MAP

30. The Mongolian khanates

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

426 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

Khubilai had just appointed as chief administrator

(p'ing-chang cheng-shih)

in

the Central Secretariat (Chung-shu sheng), one of the most influential posi-

tions in his government.

In 1260 and 1261, Khubilai sent gold and silver to Li to cover the costs of

campaigns against the Sung. Late in 1261, however, Li prepared to break

away from Khubilai and to effect an agreement with the Chinese in the

south. Having access to wealth derived from the valuable reserves of salt and

copper in Shantung, Li had the resources to mount a major challenge to

Mongolian rule. He may have received assurances of support from the Sung

and must have determined that trade and other economic relations with the

Chinese in the south could offer more benefits than could friendly relations

with the Mongols. As an ethnic Chinese, he may, in addition, have felt

loyalty to the Sung. Whatever his motivations, on 22 February 1262, he

rebelled against those whom he had earlier accepted as his overlords.

Khubilai responded immediately by dispatching several of his most trusted

military men to deal with the troublesome Chinese leader. Shih T'ien-tse and

Shih Ch'u, two of Khubilai's leading generals, together with his Confucian

adviser Chao Pi, set forth to crush Li's rebellious forces. Their numerical

superiority made itself felt within a few months, and by early August Li had

been defeated and captured. The court's troops placed Li in a sack and had

him trampled to death by their horses, a method of execution usually re-

served for princes. His father-in-law Wang Wen-t'ung was executed shortly

thereafter, and Wang's complicity in the rebellion and "treachery" was widely

publicized in order to justify his punishment.

24

Li T'an's revolt was a turning point in Khubilai's reign, for it made

Khubilai increasingly suspicious of the Chinese. A rebellion in an important

economic area led by an important Chinese leader with the covert support of

a trusted Chinese court official of the highest rank must surely have affected

Khubilai. He would, from this time on, naturally hesitate to rely exclusively

on his Chinese aides to rule China and would instead seek assistance from

non-Chinese advisers. Even before he became the great khan and the emperor

of China, Khubilai had recruited advisers from diverse ethnic backgrounds.

But Li T'an's rebellion raised even greater doubts about reliance on the

Chinese. Khubilai became more keenly aware of his need for non-Chinese

advisers and officials.

His wife Chabi supported such efforts at governance. She aspired to be the

24 Secondary studies of

Li's

rebellion include those by Otagi Matsuo, "Ri Dan no hanran to sono seijiteki

igi: Moko cho chika ni okeru Kanchi no hokensei to sono shukensei e no tcnkai,"

TSyoshi

ktnkyu, 6

(August-September 1941), pp. 253—78; Sun K'o-k'uan, "Yuan ch'u Li T'an shih pien te fen hsi," Ta

lutsachib, 13 (1956), pp. 7—15.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

KHUBILAI AND ARIGH BORE 427

empress of a powerful state, not simply the wife of a tribal chieftain.

2

' Her

patronage of officials with diverse backgrounds, especially Tibetans, also

complemented Khubilai's policies. Yet they both recognized that the bulk of

their subjects were Chinese and that some accommodation with Chinese

values and institutions was essential.

The early administrative system that Khubilai fostered was designed to

attract the support of the Chinese and to reflect the concerns of the Mongols.

Unlike the preceding Chinese dynasties, however, Khubilai's newly devised

government did not institute civil service examinations. These examinations,

preparation for which necessitated repeated exposure to and empathy for

Confucian doctrines, had since the seventh century provided many of the

officials for earlier dynasties in China, and they had been adopted by the Liao

and Chin in the north. Khubilai, however, was not anxious to commit

himself to a coterie of advisers and officials shaped by a Chinese ideology.

Moreover, he wanted the power to appoint his own officials. The institutions

he established would, nonetheless, be familiar to his Chinese subjects.

The Central Secretariat (Chung-shu sheng), a traditional Chinese govern-

mental agency, took charge of most civilian matters, as it received the reports

sent to the throne and drafted the laws. The head of the Central Secretariat

(chung-shu ling) consulted with Khubilai on major policy decisions, which

would then by implemented by six functional ministries supervised by the

prime minister of the left (tso

ch'eng-hsiang)

and the prime minister of the

right (yu ch'eng-hsiang).

26

The Privy Council (Shu-mi yuan) was responsible

for military affairs, and the Censorate (Yii-shih t'ai) spied on and wrote

reports to the emperor about the officials throughout his domains. Although

much of this framework of central administration resembled that of earlier

Chinese dynasties, the system of local control was different. China was

divided into provinces, each of which was administered by a prime minister

{ch'eng-hsiang)

who was assisted by branch offices

(hsing-sheng)

of the Secretar-

iat. The emperor also appointed special representatives

(darughachi),

usually

Mongols or Central Asians, to check on the activities of provincial officials as

well as those of the local officials of the 180 circuits (/«) into which the

provinces were divided.

25 KJ, 114, p. 2871. Francis W. Cleaves, "The biography of the empress Cabi in the Yuan shib,"

Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 3-4 (1979—80), pp. 138—50.

26 The six ministries were (a) Personnel, which oversaw the civilian officials; (b) Revenue, which

conducted censuses, collected tax and tribute, and regulated the circulation of money; (c) Rites, which

managed the court ceremonies, festivities, music, sacrifices, and entertainments; (d) War, which

operated the military commands and colonies and the postal stations, requisitioned military supplies,

and trained the army; (e) Justice, which enforced the laws and administered the prisons; and (f) Public

Works, which repaired the fortifications, managed the dams and the public lands, and devised the

rules for artisans.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

428 THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

Khubilai's political system differed from those of earlier Chinese dynasties

in significant ways. First, he divided the population into three ethnic

groups, with the Mongols occupying the most prominent positions, followed

by the so-called

se-mu

jen, Western and Central Asians. The inhabitants of

north China, known as Han

jen,

at first constituted the lowest-ranked group,

though after the conquest of south China, the Chinese of the south, known as

the Nan jen, became the lowest group and were excluded from some of the

most important civilian positions. Khubilai recognized that the Mongols

needed to retain control if they were to avoid being engulfed by the far more

populous Chinese (who outnumbered them by at least thirty to one). There

was,

in general, a much greater emphasis on control than under previous

Chinese dynasties.

Khubilai was concerned that his officials, many of whom were not Mon-

gols,

remain loyal, honest, and incorruptible. Thus "the [Mongol] censorial

system . . . was far more pervasive than any preceding one, and its degree of

tightly knit centralization was never once had in China's censorial

history.

"

21

Khubilai sought to maintain the officials' loyalty as well as to prevent their

abuse of power. Officials who were corrupt or lacked zeal in carrying out their

duties or imposed excessive taxes on their subjects were to be severely pun-

ished. Khubilai simultaneously needed new regulations to control and domi-

nate the Mongolian leadership. Many Mongolian nobles had been granted

appanages (Chinese: fen-ti) since the time of Ogodei, and within their own

areas they considered themselves supreme and brooked scant interference.

Khubilai had to bring these appanages under the supervision of the central

government, insisting that their rulers abide by the laws and regulations

devised by his government. Moreover, he anticipated that he, not the appa-

nage holders, would levy taxes and recruit a state army.

Recent studies suggest that Khubilai's efforts at control were fruitless.

One scholar writes that "with the important exception of the appointment of

officials . . . the central government's engagement in empire-wide adminis-

tration was at best transitory or limited to very restricted activities."

38

The

Central Secretariat, in this view, functioned effectively only around Khubi-

lai's old domain and his capital; Khubilai's dominance over local affairs was

not as pervasive as he wished. Similarly, his control over local officials and

appanage holders was limited. Throughout his reign, he issued edicts aimed

at corrupt or obstreperous officials, indicating that he was occasionally frus-

trated in his attempts to impose his own rule. Yet these failures should not be

exaggerated, for by the early 1260s Khubilai had established an administra-

27 Charles Hucker,

The censorial system

of Ming

China

(Stanford,

Calif.,

1966), p. 27.

28 David Farquhar, "Structure and function in the Yuan imperial government," in China

under Mongol

rule, ed. John D. Langlois, Jr. (Princeton, 1981), p. 51.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

FOREIGN EXPANSION 429

tton for China that appeared on paper

to

be workable.

It

appeared familiar

to

the Chinese,

but it

differed sufficiently from previous Chinese systems

to

accommodate Khubilai's

and the

Mongols' values

and

systems

and

their

greater need

for

controlling their subjects.

FOREIGN EXPANSION

Having established a government

in

China, Khubilai now turned

his

atten-

tion

to

foreign relations. Like

his

Mongolian predecessors, Khubilai knew

that

he had to

persist

in

territorial expansion.

His

success

as a

ruler,

in

Mongolian eyes, would

be

measured

in

part

by his

ability

to

incorporate

additional wealth, people,

and

territory into

his

domain. Similarly,

the

Chinese believed that a good ruler would induce foreigners

to

submit and

to

accept China's supremacy. They would

be

inexorably attracted

to

China

because

of

the ruler's virtue

and the

glory

of

his state. Both

the

Mongolian

and

the

Chinese worldviews thus

led

Khubilai

to

emphasize expansionism.

The manner

in

which

he

came

to

power may also have impelled

him to

seek

foreign conquests. Because he had been challenged by his own brother, there

was

a

real question

of

his legitimacy

as the

ruler

of

the Mongolian world.

Khubilai

may

have tried

to

quell such doubts

by

embarking

on

foreign

military campaigns,

as

additional conquests would bolster

his

reputation

among the Mongols.

The conquest

of

the Sung

Khubilai's campaigns against

the

southern Sung were also prompted

by

considerations

of

security. Like any other Chinese dynasty, the Sung aspired

to reunify China. Revanchism played

an

important part

in

policy debates

at

the Sung court,

and

though

the

Sung military

was

at

that time relatively

weak

and

did not

pose

any

immediate threat

to

the

Mongols,

it

could

be

revitalized,

and one of its

first objectives would

be the

retrieval

of the

northern Chinese lands conquered

by the

Mongols. Khubilai would seek

to

subjugate

the

Sung before

it

could become

a

more powerful adversary.

The

Sung's considerable wealth

was

still another attraction.

The

land

in

south

China was fertile,

a

vital consideration

for

the north, whose population often

outstripped

its

food supplies

and

which could make good use

of

grain

sur-

pluses from the south. The Sung's seaborne trade with Southeast Asia, India,

and the Middle East had enriched its coastal towns, another economic induce-

ment

for

Khubilai.

But the conquest of south China entailed numerous obstacles. Though

the

Mongolian armies

and

cavalry

had

been successful

in

northern climates

and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

43° THE REIGN OF KHUBILAI KHAN

terrain, they were not accustomed to the climate or terrain of

the

south. They

were not prepared for the punishingly high temperatures of the semitropical

regions of south China. Neither were they ready for the diseases, the para-

sites,

and the mosquito-infested jungles in the south and southwest. Their

horses could not readily adjust to the heat; nor could they forage as easily in

the southern farmlands as they could in the steppe. The Mongolian troops, in

addition, needed to employ military techniques they had scarcely, if ever,

used before. To cope with the Sung navy, for example, they would be

required to construct boats, recruit sailors, and become more proficient in sea

warfare. On land, they would need to lay siege to populous, well-defended

towns and cities. In fact, the Sung had the largest population and the most

resources of any of

the

lands invaded by the Mongols. The subjugation of this

great Chinese empire would thus entail enormous expense and effort.

The Sung was, on the surface, prosperous. Such lively cities as the capital,

Hang-chou, craved and had the resources to pay for luxuries. Hang-chou had

splendid restaurants, tea houses, and theaters; "no other town had such a

concentration of wealth."

2

' Southern Sung prosperity derived from both

widespread domestic trade and commerce with other countries in Asia and

the Middle East. The Sung government, recognizing the potential revenues

to be garnered from trade, appointed maritime trade superintendants

(t'i-chii

shih-po sbih)

in the most important ports, employed merchants to supervise

the state monopolies and allotted them a higher status in society, and encour-

aged foreign merchants to trade with China. As the seaborne commerce

flourished, the Sung's concern for shipping and, as a result, for naval power

grew. The court developed the navy to counter piracy along the coast, and its

great ships with their rockets, flamethrowers, and fragmentation bombs

became an important branch of the Sung armed forces, posing an obstacle to

Mongolian conquest.'

0

Despite its commercial prosperity and its naval power, the Sung confronted

serious internal political and economic difficulties by the middle of the thir-

teenth century. Many

large

landlords had, through good management, oppres-

sion of the peasants, or favors from relatives in the bureaucracy, accumulated

vast estates and had been granted

a

tax-exempt status. As more and more land

was removed from the tax rolls, the court could not meet its fiscal obliga-

tions.

Eunuchs and relatives of the empresses played important roles in court

deliberations on policy, occasionally overruling high officials. The expendi-

29 Jacques Gernec, Daily life in China, on the

eve

of the Mongol invasion, 1250-1276, trans. H. M. Wright

(New York, 1962), p. 84. On Hangchow, see also Arthur C. Moule, Quinsai, with other

notes

on Marco

Polo

(Cambridge, 1957).

30 Lo Jung-pang, "Maritime commerce and its relation to the Sung navy," Journal of the

Economic

and

Social History of the Orient, 12 (1969), p. 81.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008