?tekauer Pavol, Lieber Rochelle. Handbook of Word-Formation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

FORMATION

16

7

A

n insightful method to treat the inherently compositional nature of word-

formation processes was proposed by All

e

n

(1978) applying the ‘IS A’ Condition to

English compounds like the following

:

1

9

(

30) [[high]

A

[school

]

N

]

N

T

he ‘IS A’ Condition allows the identification of the compound’s head in

s

emantic and categorial terms:

•

IS

high school A type o

f

high

o

r IS it A type of

school

?

•

G

iven that high is an adjective and

school

is a noun: IS

l

high school

A

N

adjective or IS it A noun?

A

high school ‘IS A’ (type of)

school

and it ‘IS A’ noun

,

hence

school

is the

l

h

ead of the compound

h

igh school

.

Looking back at the compounding rule in (11c),

w

e can generalize that in an English compound [X+Y]Z, Z ‘IS A’ Y, both from a

c

ate

g

orial and a semantic point of view.

A

lthou

g

h ‘IS A’ ma

y

correctl

y

tell us which

o

f the constituents is

p

redominant in

a complex word, it says nothing about the mechanisms that bring about this

asymmetry. Lieber (1980) presents a system

of rewriting rules th

m

at generate binary-

branching tree structures whose terminal nodes are filled by stems and affixes,

d

epending on their subcategorization frames. In this system the ‘IS A’ Condition is

explained on strictly formal terms: the essential property of a morphological head is

t

hat all its features (whether semantic or categorial) are copied to the upper node of

t

he structure. Lieber reformulates the ‘IS A’ Condition as the F

eatu

r

e

-P

e

r

colation

Convention

.

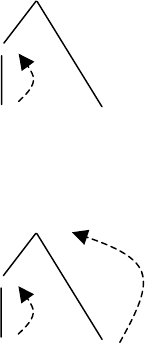

We illustrate this in sim

p

lified form with the wor

d

h

a

pp

iness

:

(

31) a. The features of a stem are passed to the first dominating non-

A

happ

y

A

n

ess

N

b. The features of an affix are passed to the first dominating node

w

hi

c

h

b

ran

c

h

es

N

A

happ

y

A

n

ess

N

1

9

This notion had been previously explored, though in different terms, for example by Marchand (1969).

168

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

ARA

B

oth the ‘I

S

A’

C

ondition and the Feature-Percolation

C

onvention were

d

esigned to account in formal terms for one of the most crucial notions in

m

orpholo

gy

: the notion of

head

. Aronoff (1976) extended the use of ‘head’ to

i

n

c

l

ude bo

th

wo

r

ds

an

d bou

n

d

f

o

r

ms

(

affixes

)

. Williams

(

1981

)

further elaborated it

,

proposin

g

the Ri

g

ht-Hand Head Rule

(

RHR) for En

g

lish: all morpholo

g

icall

y

c

om

p

lex words are headed, a

n

d the head in a com

p

lex st

r

ucture is the rightmost

element. The validity of his rule can be tested with prefixed, suffixed and compound

words

(

32a

)

and can be ex

p

ress

e

d with a general schema (32b):

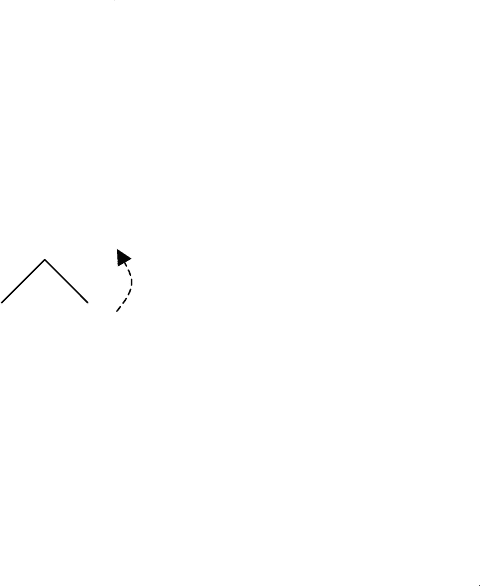

(

32

)

a. [re+ [write]

V

]

V

[[happy]

A

ness

]

N

[[

black

]

A

[

board

]

N

]

N

b.

Y

XY

r

e

w

rit

e

happy ness

b

la

c

k

bo

ar

d

I

n all these cases, the ri

g

htmost

e

l

e

m

e

nt h

e

a

ds

th

eco

n

s

tr

uc

ti

o

n

:

rew

r

ite

i

s

a

ve

r

b

bec

a

use

w

r

ite

is a verb

,

ha

pp

iness i

s

a n

ou

n

bec

a

use

-

ness

forms nouns and, finally,

blackboard

is a noun because

d

board

is a noun.

d

A

logical generalization stemming from the RHR is that prefixes are neve

r

h

eads, while suffixes always are. This generalization, although correct for a great

n

umber of cases, is too strong and needs to be weakened: for instance, some prefixes

d

o indeed seem to be heads

(

cf.

rich

ĺ

en

+

rich

)

while evaluative suffixes and

i

nflectional affixes in

g

eneral do not qualif

y

as heads (cf.

book

+

let

,

want+ed

). As

d

d

for compounds, subsequent research has shown that the RHR is not a universal

principle but that it depends on the

ty

polo

g

ical affiliation of the lan

g

ua

g

es

c

onsidered: for instance, compounds in the Romance languages are systematically

l

eft-headed

(

cf. It.

uo

m

o

r

ana

‘lit. man-frog, frogman’)

.

20

The very concept of ‘head’ has been

s

trongly criticized. An extreme position,

d

efended by Bauer (1990), sugg

e

sts that the possibility that

the notion of head has

t

n

o place in morphology should b

e

al

so

tak

e

n int

o

a

ccou

nt

.

2

1

Nevertheless

,

the notion of head is

s

t

ill a fundamental one in morphology for it

g

rants important insi

g

hts into the functionin

g

of man

y

re

g

ular phenomena: the head

i

n a complex word is usuall

y

the locus of inflection (cf.

h

i

g

h school

ĺ

hi

g

h schools

20

Note that while derived words are always

e

n

docentric and by and large right-headed, compounds

e

xhibit a variet

y

of possibilities: (

a

)

head in the ‘canonic’ location

(e

.g

. ri

g

ht for Germanic lan

g

ua

g

es,

l

eft for Romance languages), (b) no heads (cf. the ‘exocentric compounds’, also called

bahuv

r

ihi

,

such

a

s

pale fac

e

)

,

(

c

)

two heads

(

dvandva

com

p

ounds, cf. S

p

.

poeta-pintor

‘poet-painter’), (d) head in the

r

‘

wrong’ place (cf. It.

te

rr

emoto

‘earthquake’ a right-headed word due its Latin diachronic origin).

21

Even the position taken by Bauer has been criticized. Cf. Štekauer

(

2001

)

.

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WORD

-

FORMATION

169

an

d

It

.

capostazion

e

‘

s

tati

o

n ma

s

t

e

r’ ĺ capistazione

)

, it is the constituent fro

m

w

hi

c

h r

e

l

ev

ant inf

o

rmati

o

n percolates to the uppe

r

node, its position in compounds

i

s strongly related to the word-order type of the language (SVO languages tend to

h

ave left-headed compounds, while SOV lan

g

ua

g

es tend to have ri

g

ht-headed

o

n

es

22

).

Morpholo

g

ical theor

y

has often benefited from pro

g

ress in s

y

ntactic theor

y

. Fo

r

exam

p

le, Selkirk

(

1982

)

23

extended the hierarchical

pr

o

jections of the so-called

X

-bar schema to apply in morphology

:

24

the maximal morphological projection is

ide

nti

c

al t

o

th

e

X

0

level projection in syntax (i.e. words)while

,

below

X

0

,

two purely

m

orphological projections exist: Root (

X

-

1

)

and Af. The internal structure of

happiness an

d

monst

r

ous

would, therefore, be represented as in (33):

(

33

)

Word

(

N

0

)

Word

(

A

0

)

Word

(A

0

)

Affix Root

(A

-1

)

Root

(

A

-

1

)

-ness Root

(

N

-

1

)

Affix

happ

y

monstr- -ous

The similarity between morphology and syntax, however, is not complete. Fo

r

i

nstance, affixes do not have X-bar level: they are a peculiarity of W-syntax (the

syntax of words, morphology), having no parallel in S-syntax (syntax proper).

I

n addition, while in S-syntax it is common that non-maximal pro

j

ections

dominate other maximal pro

j

ections,

2

5

Selkirk argues that the same is not true of

m

orphology: she proposes a universal principle that, only in the domain of

W

-s

y

ntax, no constituent can dominate a constituent of hi

g

her X-bar level. This

m

eans that Words ma

y

contain Roots, but not vice versa; at the same time, both

W

ords and Roots ma

y

freel

y

contain Affixes, for the

y

do not have X-bar level.

22

En

g

lish, bein

g

an SVO lan

g

ua

g

e with ri

g

ht-headed

c

ompounds, is a counterexample to this statement.

H

owever, this can be explained in diachronic t

e

r

ms: English right-headed compounding is a remnant

o

f an earlier dominant SOV word order. It is wid

e

l

y accepted that there was a

s

hift in

wo

r

do

r

der

between Old and Middle English: Old English was SOV (like Proto-Indo-European) while Middle

English was mainly SVO (cf. Kemenade 1987, Lightfoot 1991).

23

Selkirk, while remainin

g

committed to the Lexicalist

hy

pothesis, presents a n

e

w

point of view: rathe

r

than highlighting the differences between morphology

and syntax, she explores the degree to which

y

t

hey resemble each other. The extent of this si

m

i

larity in Selkirk’s framew

o

rk

co

n

ce

rn

s

th

e

f

o

rmal

apparatus of both components. W-sy

ntax and S-syntax make use of

the same context-free rewriting

f

r

ules and of the lexical categories N, A and V.

24

Cf. section 7 below for other issues concernin

g

the application of X-bar theor

y

to morpholo

g

ical

p

henomena.

2

5

Cf.

[

the

[[

train

]

N

0

[[[

to

]

P

0

]

P

1

[[[

London

]

N

0

]

N

1

]

NP

]

P

P

]

N

1

]

NP

, where, for example, the projection N

1

h

eaded b

y

t

r

ain

contains a maximal pro

j

ection of the preposition

to

(

PP

)

.

170

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

AR

A

5

.1 Stron

g

and Weak Lexicalism

Stemming from Chomsky’s (1970) proposal that semantically irregula

r

de

ri

v

ati

o

n

s

h

ou

l

d

n

o

t

be

accounted for by the syntax (the beginning of Lexicalism),

t

here developed two opposed theoretical positions.

Th

e

S

tron

g

Lexicalist H

y

pothesis

t

akes Chomsk

y

’s su

gg

estion to its extreme

c

onsequences, excludin

g

all morpholo

g

ical phenomena from the s

y

ntax: the

processes of word formation and the rules of inflection are applied pres

y

ntacticall

y

,

i

n the Lexicon. This position was origi

n

ally proposed in Halle’s (1973) seminal

paper on generative morphology and it has bee

n

widely assumed as part of the most

i

nfluential theories of syntax (e.g. Lexical Functional

G

rammar

,

G

eneralized Phrase

S

tructure

G

rammar

,

H

ead-Driven Phrase

S

tructure

G

rammar

,

and to some extent

–

at least regarding inflectional morphology and checking theory – also by the

Minimalist Program).

The Stron

g

Lexicalist H

y

pothesis is usuall

y

supplemented b

y

the assumption that

s

y

ntactic rules cannot modif

y

, move or delete parts of words: this is the so-called

Principle o

f

Lexical Inte

g

rit

y

, which has been endorsed b

y

a

g

reat number of

m

orphologists (cf. Lapointe 1980, Di Sciullo & Williams 1987, among others) and

c

onstitutes one of the key ideas of

S

trong Lexicalism

.

This

p

rinci

p

le can be defined

as

(

34

)

, in its most radical formulation:

(

34) Generalized Lexicalist H

y

pothesis (Lapointe 1980: 8)

No s

y

ntactic rule can refer to elements of morpholo

g

ical structure

The Strong Lexicalist Hypothesis demands a sharp division between syntax and

m

orphology and, as such, it cannot account for a variety of phenomena that require

some degree of interaction of these two components of the grammar.

Th

ed

i

s

tin

c

ti

o

n

be

t

wee

n

de

ri

v

ati

o

nal m

or

phology (realized in the Lexicon) and

r

r

i

nflectional morpholo

gy

(accomplished b

y

the s

y

ntax) achieves a

g

reater de

g

ree of

d

escriptive accurac

y

. This position is known as the Weak Lexicalist H

y

pothesis an

d

(

in general) it has had more success among morphologists than among syntacticians.

A

ronoff (1976) acknowledged a Weak Lexicalist framework, as did many others

t

hereafter. The stand

p

oint received a

de

tail

ed

a

ccou

nt f

o

r th

e

fir

s

t tim

e

in

A

nderson’s classic pape

r

Where’s Morphology

?

(

1982

)

.

A

ll in all, over a ten-year period, the Lexicalist approach in morphology

d

eveloped a very rich body of hypotheses and principles, of which only a few have

been discussed in the precedin

g

sections. W

e

ha

ve

n

o

t m

e

nti

o

n

ed

m

an

y

others such

a

s

th

e

Ad

j

acenc

y

Condition (Sie

g

el 1978),

26

which develo

p

ed into the A

tom

Condition of Williams (1981), inheritance of Ar

g

ument Structure (Sproat 1985,

B

ooij 1988), etc.

Lexicalism has been a

pp

lied to an eve

r

growing number of languages and topics

r

suc

h a

s

th

e

nat

u

r

eo

f th

eso

-

c

all

ed

evaluative suffixes and clitics (Zwicky 1985),

26

Which inspired a great number of proposals, such as Pesetsky’s (1979)

B

racket Erasure Convention

,

W

illiam’s

(

1981

)

Atom

C

ondition

,

La

p

ointe’s

(

1981

)

for his Lexical Integrity Hypothesis

,

Kiparsky’s

(

1982

)

B

racketing Erasure Principl

e

,

Botha’s

(

1981

)

M

orphological Island Constrain

t

,

among others.

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WORD

-

FORMATION

171

allomorphy (Carstairs McCarthy 1987), bracketing paradoxes (Spencer 1988), the

o

rganization of so-called non-linear mo

r

phologies (McCarthy 1982), the interface

between different components of the grammar (for example, between morphology

and s

y

ntax, see to name but one Zwick

y

1986; or between morpholo

gy

and

phonolo

gy

, cf. Booi

j

& Rubach 1987).

C

ertainl

y

, such an empirical ferment over a short period of time also brou

g

ht into

t

he

p

icture data that could not be acco

m

modated in the original theory, and

t

herefore

,

different branches of lexicalis

m

develo

p

ed. To be sure, Lexicalism was

n

ot the only theory of morphology: at the same time other theories developed such

as Natural Morphology (cf. Dressler et al

.

1987), to mention but one, giving rise to a

r

ich theoretical debate, which is still today very intense (cf. for example, Fradin &

Kerleroux 2003

)

.

6

. M

O

RE

O

N THE N

O

TI

O

N

O

F LEXI

CO

N

R

esearch in theoretical lin

g

uistics has remarkabl

y

enriched the notion ‘Lexicon’:

b

y

movin

g

awa

y

from the earl

yg

enerative viewpoint (cf. section 3), much more

elaborated hypotheses of lexical representations have been proposed. These

d

evelopments often involve the inclusion of information depicting the Pr

edicate

Argument Structure

(

PAS) and/or some kind of complex semantic description o

f

l

exical items (usually termed Lexical Conceptual Structure

,

LCS). Typical minimal

entries in such a Lexicon could be represented as follows (cf. Lieber 1992: 22):

(

35

)

a.

enter

[V ___ ]

r

[

¥'

n

t

'

(

r

)

]

LCS:

[

Event

GO

t

(

[

Thin

g

]

,

[

Path

TO ]

(

[

Pla

ce

IN

(

[

Thin

g

]

)

]

))

]

PAS: x <

y

>

b.

cat

[N ___ ]

t

[

¥

k

æ

t

]

LCS:

[

Thin

g

]

F

or instance, in

(

35a

)

enter

reads as a verb pronounced [

r

ε

ntr

]

whose LCS

desc

ri

bes

an a

c

ti

o

n in

vo

l

v

i

n

g two entities, one of which goes into the other;

ente

r’

s

PAS says that it has two arguments, x (external) and y (internal and, in this case,

n

on-obli

g

ator

y

).

Given such a conception of lexical representations and of the operations that can

be a

pp

lied to them, the domain of mor

p

hol

o

gy (traditionally und

e

r

stood as the study

o

f the internal structure of words) has been extended to include also the study of the

external valency of words (the effects of morphology on PAS

27

)

.

2

7

Whether there is an inde

p

endent PAS slot in lexical entries is open to question; some linguists assume

t

hat PAS is derived from LCS, as a sort of “summar

y

”

of its contents as far as it visible to s

y

ntactic

processes.

17

2

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

ARA

W

hile it is generally agreed that words are represented in the Lexicon (i.e. they

h

ave a full lexical entry of the kind seen above), whether affixes are lexically

r

e

p

resented is much more controversial. These issues demand a

p

rinci

p

led formal

d

istinction between ‘word’ and ‘affix’, and this is not a simple distinction to draw.

There are two basic viewpoints:

(

36

)

a. words and affixes are lexical items

(

both have full lexical entries

)

b. words and affixes are different (only words have entries in the

Lexicon

)

A

mong others, Halle (1973), Lieber (1980) and Selkirk (1982) ascribe to the

hy

pothesis (36a), which has been supported b

y

numerous ar

g

uments, for example:

•

W

ords and affixes often exhibit the same relations among them (synonymy,

antinomy, hyponymy, polysemy, cf. Lehrer 1996)

•

Sometimes, a unit clearl

y

identifiable as an affix on formal

g

rounds seems to

carry the kind of meanings expressed by

roots in other languages (cf. Mithun

y

1996

)

•

Bo

th

wo

r

ds

an

d

affix

es

ha

ve

l

e

xi

c

al

c

ategory and subcategorization frames (cf.

Lieber 1980, 1992, Williams 1981, Selkirk 1982

)

.

•

B

oth words and affixes take part in X-bar structures (Selkirk 1982), suffixes, in

particular, seem to share the basic prop

e

r

ties of s

y

ntactic heads in complement-

h

ead structures

(

Di Sciullo 1995

)

.

Hypothesis (36b) was first proposed in a Lexicalist framework by Aronoff

(

1976) and has become the hallmark of word-based theories of morphology: only

‘words’ are represented in the Lexicon, ‘affixes’ are assimilated to rules and operate

i

n a different submodule of the

g

rammar. The ar

g

uments for this position are also

n

umerous; its main a

pp

eal lies in the re

p

resentation of non-concatenative

phenomena such as umlaut, allomorph

y

, suppletion, all of which cannot be easil

y

explained by hypothesis (36a) as combinations of words and affixes. Furthermore

,

as

D. Corbin (1987) pointed out, if affixes and words have the same representation,

t

here would be no possible distinction to be drawn between compounding and

d

erivation: crucially, though, in some

l

anguages compounds and derived words are

s

ystematically different (e.g. compounds in the Romance languages are left-headed,

while derived words are ri

g

ht-headed, cf. It.

uo

m

o

r

ana

‘lit. man-fro

g

, fro

g

man’ vs.

ba

r

ista

‘bar man’

)

. If words and affixes are not differentiated, interestin

g

g

eneralizations such as this one will be lost.

I

t ha

so

ft

e

n

bee

n

obse

r

ved

that th

e

L

e

xi

c

o

n may contain a wide range of different

entities, produced not only by morphological processes but also by syntactic

o

perations. Di Sciullo & Williams (1987: 14

)

propose a “hierarchy of listedness” fo

r

t

he contents of the Lexicon, which they consider to be “like a prison – it contains

o

nly the lawless, and the only thing that its inmates have in common is lawlessness”:

(

37

)

– All the mor

p

hemes are listed.

– ‘M

os

t’

o

f th

ewo

r

ds

ar

e

li

s

t

ed.

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

F

ORMATION

173

– Many of the compounds are listed.

– Some of the phrases are listed.

– F

ou

r

o

r fi

ve o

f th

ese

nt

e

n

ces

ar

e

li

s

t

ed.

This does not mean that we cannot distin

g

uish between morpholo

g

ical and

sy

ntactic ob

j

ects; Di Sciullo & Williams emphasize the Lexicon’s role as stora

g

e fo

r

whatever linguistic object needs to be memo

r

ized by speakers. The elements of the

L

exicon for Di

S

ciullo

&W

illiams are all called

listemes

(whether they are words,

affixes or

p

hrases

)

.

7

. LEXI

C

ALI

S

M T

O

DAY

The Lexicalist Hypothesis in its strong version is rather difficult to maintain with

r

espect to a series of counterexamples that have been highlighted by empirical

r

esearch. These countexamples lead some lin

g

uists to conceive the morpholo

g

ical

c

omponent as havin

g

some

obli

g

ator

y

interaction with the s

y

ntax. The extent of this

i

nteraction, as conceived in various studies, ran

g

es from the so-called Weak

L

exicalist Hypothesis (which assigns inflectional morphology to the syntactic

c

omponent), to the opening of some systematic areas where morphology and syntax

“

talk” to each other, to the complet

e

a

ccou

nt

o

f all m

or

phological phenomena by

rr

m

eans of syntactic operations (which amounts to the exact opposite of lexicalism).

B

elow we will discuss some problems of the lexicalist approach and evaluate to

w

hat

e

xt

e

nt it

c

an

s

till

be co

n

s

i

der

ed a

p

roductive theoretical framework.

Stron

g

Lexicalist models are essentiall

y

linear

:

28

the morpholo

g

ical component

(Lexicon + Word Formation Rules) provides simplex and complex words, feedin

g

t

he structures created by syntax. The

o

nly point of contact between the two

c

omponents in these models is lexical insertion, the mechanism by which the

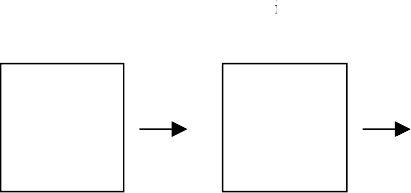

terminal nodes in a syntactic tree are ‘f

illed’ with words. The following is a

f

f

s

implified schema of this relation:

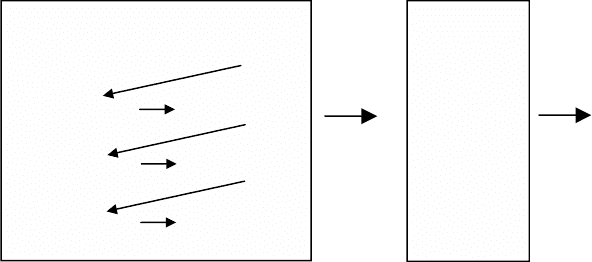

(Phonology,

Lexical Semantic

Insertion Interpretation)

````

Figure

3

In a picture such as this one, communication between morphology and syntax is

k

ept to a bare minimum. The Lexicon feeds the initial point of s

y

ntactic derivations,

2

8

There are also other types of models. Cf. for example the so-called ‘parallel morphology’ (Borer 1991,

Sadock 1991

)

.

Morphology

(

Lexicon +

W

FRs

)

S

y

nta

x

1

74

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

AR

A

l

eaving phonological and

s

emantic interpretation to take place after the syntactic

c

om

p

utation is done.

7.1 Inflectional morphology

Most morphologists working within the lexicalist framework assumed that

derivation and inflection are different morpholo

g

ical processes

.

29

I

n particular, Anderson (1982) defined inflection as the morpholo

gy

that “

is

r

elevant to the s

y

nta

x

”

: inflectional morpholo

gy

reali

z

es

all the morphos

y

ntactic

features of a word

(

Plural, Indica

t

ive, Active, etc., each specifying a

m

orphosyntactic category such as Number, Mood, Voice) depending on the

s

yntactic context in which the word is inserted. Inflection plays, therefore, the role

o

f “ad

j

usting” the words provided by the Lexicon to the morphosyntactic

r

equirements of the syntax. Anderson proposed a Weak version of Lexicalism,

c

laiming that the rules of inflectional morphology apply after syntax, intermixed

with phonolo

g

ical rules; consider the architecture of Anderson’s proposal (details

o

mitted

):

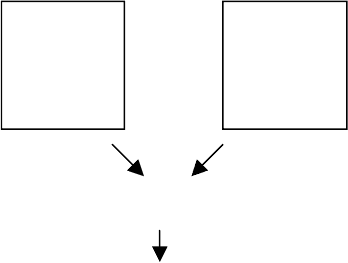

30

L

e

xi

c

al

In

se

rti

o

n

(Phonology,

Inflectional Morphology,

Semantic Interpretation)

F

i

g

ure 4

Other linguists assume that inflection and derivation are instances of the same

op

eration, i.e. affixation, but that the diff

e

r

ences between them can be ex

p

lained as a

m

atter of ‘ordering’. This approach is d

e

fended in Kiparsky’s (1982, 1983) model of

29

Cf., amon

g

others, Aronoff (1976), Scalise (1988) and Anderson (1982, 1992). The opposite view has

been also maintained however, cf. among others Halle (1973), Lieber (1980).

30

Realization-based models of morphology (e.g.

A

n

derson 1992, Stump 2001) continue in some way the

d

i

ssoc

iati

o

n

o

f th

e

infl

ec

ti

o

nal an

d

d

erivational rule types (defining

r

espectively inflect

ed wo

r

d

f

o

rm

s

v

s. lexemes

)

.

Morphology

(

Lexicon +

W

FRs

)

S

y

nta

x

T

HE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WORD

-

F

ORMATION

175

Lexical Morphology

:

3

1

he assumes that both word-formation rules and phonological

r

ules apply in the Lexicon in an orderly progression of cycles. Without attempting to

i

llustrate the details of the theory, Kiparsky’s model can be represented as in Figure

5.

Morpholo

g

ical rules are assi

g

ned to ordered levels. Inflectional rules are

assi

g

ned to a later level than derivati

o

nal and compoundin

g

rules (thus explainin

g

why inflection usually appears outside derivation). Each morphological level is

paired with a class of specific phonological rules: the output of a word-formation

r

ule is sent to the phonological rules of that level

.

32

(

Postlexical

Phonology

,

S

emantic

L

e

xi

c

al

I

nterpretation)

I

n

se

rti

on

Fi

g

ure 5

A

s it can be seen, both Anderson’s and Kiparsky’s proposals highlight that

i

nflection is a problem for the strong lexicalist model in Figure 3. An alternative

point of view has been proposed by Booij (1996, 2002: 19-20) who claims that there

are two types of inflection:

i

nherent inflection (which “adds morphosyntactic

properties with an independent semantic value to the stem of the word”) and

contextual inflection (“required by the syntactic context, but [which] does not add

i

nformation”

)

. A functional continuum ra

ng

in

g

from strictl

y

word-formin

g

processes

(lexical) to strictl

y

contextual inflection (s

y

ntactic) can be ima

g

ined, placin

g

i

nh

e

r

e

nt infl

ec

ti

o

n

so

m

ew

h

e

r

ec

l

ose

r t

ode

ri

v

ati

o

n

.

Thi

sd

i

s

tin

c

ti

o

n

c

an a

ccou

nt f

or

t

he fact that, sometimes, inherent inflection (but never contextual inflection) may

feed WFRs: com

p

aratives and su

p

erlatives are found as

p

arts of com

p

ounds and

de

ri

ved wo

r

ds.

3

1

Developing from Siegel’s (1974) Level Ordering Hypothesis, the theory of Cyclic Phonolog

y

developed in Mascaró (1976) and Pesetsky

(

1979

)

. A number of different versions of L

exical

M

orphology/Phonology

h

ave been proposed, somewhat differing with respect to the characterization

o

f rules (morpholo

g

ical or phonolo

g

ical) or proposin

g

a

d

iff

e

r

e

nt l

eve

l-

o

r

de

r

in

g

or

g

anization (cf.

Mohanan (1986), Kiparsky (1985), Halle & Mohan

a

n

(1985), Booi

j

& Rubach (1987)). All these

approaches embrace Strong Lexicalism, but at the cost of enhancing the Lexi

c

on

(

which now, besides

W

FRs, must contain phonolo

g

ical rules).

32

The rules of lexical phonology are cyclic because th

e

y apply at each level of word-formation, before

t

he next level can take place. On the other hand, the rules of postlexical phonolo

gy

appl

y

after all

word-formation and s

y

ntactic processes have taken place (the

y

are not c

y

clic).

L

e

xi

co

n

Un

d

er

i

ve

d

i

tems

Level 1 morph. Level 1 phon.

Level 2 morph. Level 2 phon.

Level n mor

p

h. Level n

p

hon.

S

y

nta

x

1

76

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

AR

A

7.2 Syntactic Morphology

One of the key arguments against the Lexicalist Hypothesis has been Occam’s

r

azor: if it can be demonstrated that a satisfactor

y

explanation of morpholo

g

ical

phenomena is achievable without an

y

additiona

l

theoretical apparatus (i.e. onl

y

with

t

he instruments of s

y

ntax and, more rarel

y

, phonolo

gy

), then dispensin

g

with the

m

orphological component of the grammar is a desirable effect for linguistic theory.

This idea has, in one way or another, dominated the theoretical debate since the

1990’s: develo

p

ments in recent theories of

s

yntax seem (more) capable of dealing

with processes of word-formation than they were in the 1970’s.

Syntactic models of morphology argue that word-formation phenomena follow

s

yntactic constraints, interacting with syntactic operations, and that they should be

s

ubsumed within the s

y

ntactic component.

7.3 The Syntactic Incorporation Hypothesis

Incor

p

oratio

n

33

has been at the center of many

t

h

eo

r

e

ti

c

al

d

i

scuss

i

o

n

s bec

a

use

it

c

onsists of a “formally morphological process with syntactic implications” (Mithun

2000: 923-24). The central issue of this debate is whether incorporation is a lexical

o

r a syntactic process. Consider the

e

xample (38a), a prototypical case of

i

ncorporation from Classical Nahuatl and

t

he synonymous syntactic construction

(

38b

)(

Iturrioz Leza 2001: 715

)

:

b.

n

i-c-qua in naca-tl

1

S

G

.

S

U

B

J

-3

S

G

.

OB

J

-e

at

D

E

T

m

e

at-ABS

‘I eat

(

the

)

meat’

The complex verb

naca

-

qua

in (38a) is formed b

y

incorporatin

g

the noun

naca

i

nto the verb. In true incorporating languages, both the incorporated NV sequence

(

38a) and the full sentence in (38b) are semantically equivalent and grammatical.

B

aker (1988) analyzed such constructions as involving “the syntactic movement

o

f a word-level category from its base pos

i

ti

o

n t

oco

m

b

in

ew

ith an

o

th

e

r

wo

r

d

-l

eve

l

c

ategory” (Baker 1988: 424). Baker’s syntactic incorporation hypothesis i

s

developed within the framework of

Government-Binding

(Chomsky 1981): it is

g

desc

ri

bed

a

s

an in

s

tan

ce o

f h

e

a

d

-t

o

-h

e

a

d

m

ovement that leaves a trace (a properl

y

g

overned empt

y

cate

g

or

y

) with which the moved element must be co-indexed.

C

onstraints on the process are explained b

y

the

E

mpt

y

Cate

g

or

y

Principl

e

:

th

e

c

rucial

p

oint is that a trace of the incor

p

orated element must be an argument of V,

33

The best-known type of incorpora

t

ion involves adding the internal argument (i.e. direct object) into the

v

erb but many other patterns are attested (e.g. ver

b

incor

p

oration,

p

articl

e

incor

p

oration,

p

assive

i

ncor

p

oration,

p

ronoun inco

rp

oration, cf. Mithun 2000, Iturrioz Leza 2001

)

.

(

38

)

a.

n

i- naca-

q

ua

1

S

G

.

SU

BJ m

e

at-

e

at

‘I meat-eat’