?tekauer Pavol, Lieber Rochelle. Handbook of Word-Formation

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

14

7

Štekauer, P. and R. Lieber (eds.), Handbook o

f

Word-Formation

,

14

7

—18

7.

© 2005 Springer. Printed in the Netherlands.

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO

WORD-FORMATION AND THE NOTION OF THE

LEXICON

1

SERGIO SCALISE AND EMILIANO G

U

EVARA

1. A DEFINITI

O

N

Th

e

t

e

r

m

L

exicalism

refers to the theoretical standpoint in modern generative

l

inguistics according to which the process

e

s

that form complex words (derivation

and compoundin

g

2

) are accounted for by a set of L

exical

R

ules

,

i

ndependent of and

d

i

ff

erent

f

rom the s

y

ntactic rules of the

g

rammar (i.e. word formation is not

performed b

y

s

y

ntactic transformations). Such Lexical Rules are assumed to operate

i

n a pres

y

ntactic component, the L

exicon

.

The Lexicalist approach to word-formation can be said to begin in the early

1970s with two fundamental articles: Chomsky’s

R

emarks on Nominalizations

(

1970

)

and Halle’s Prolegomena to a Theory of Word Formation

(

1973

)

. Since then,

l

exicalism developed in a linear and constant way with an impressi

ve se

ri

es o

f

wo

rk

s

which contributed to shape a model that – in its basic tenets – has been adopted now

for more than 30 years.

Sie

g

el (1974) desi

g

ned a level-based morpholo

g

ical model while Jackendoff

(1975) explored the relation between the formal and the semantic parts of

m

orpholo

g

ical operations b

y

means of Redundanc

y

Rules. Shortl

y

after, Aronoff

(

1976

)

established the foundations of the whole disci

p

line with the first

c

omprehensive monograph in generati

v

e morphology. Focusing on derivational

processes, Aronoff improved the notion of rule and developed an articulated syste

m

o

f restrictions in order to constrain the excessive power of

W

ord Formation Rules

(WFRs); he also envisioned the relevance of the notion of productivity and proposed

a word-based morpholo

gy

.

Man

y

specific studies were to follow, extendin

g

the Lexicalist approach to an

e

ver-

g

rowin

g

variet

y

of lan

g

ua

g

es and issues. Amon

g

them we can mention Booi

j

(1977) on Dutch, Allen (1978) on English, Pesetsky (1979) on Russian, and Scalise

(

1980

)

on Italian. Still, numerous othe

r

p

ublications introduced new fundamental

c

oncepts which contributed to build up a complete and consistent morphological

1

We have been able to write this

c

hapter also thanks to funding by the Italian Ministry of Research and

U

niversit

y

. We would like to thank Stephen And

e

r

son, Geert Booi

j

, Rochelle Lieber and Pavol

Štekauer for their comments on previous drafts. W

e

are

g

rateful to Ni

g

el James for lookin

g

over ou

r

En

g

lish. Needless to sa

y

, the authors are solel

y

re

s

ponsible for the final version of this chapter. Even

though we discussed together the whole plan of this chapter, Sergio Scalise is responsible for sections

2 through 4, and Emiliano

G

uevara, 5 through 8.

2

Generally, though some versions of lexicalism explain also inflection by means of lexical rules. Cf.

sec

ti

o

n 5

.

1

be

l

ow.

1

48

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E & EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

AR

A

theory: for example, Lieber (1980) proposed the mechanism of feature percolation

,

W

illiams

(

1981

)

formulated an im

p

or

t

ant generalizati

o

n on morphological

heads

,

Selkirk

(

1982

)

refined the

l

evel ordering hypothesis

,

Anderson (1982), brought

i

nflectional morphology into the picture. This list of publications is far from being

c

omprehensive or even fair to the many scholars who took part in the developments

o

f lexicalist morphology: the approach gradually developed into an articulate set of

hy

potheses, an autonomous vocabular

y

and specific anal

y

tic techniques.

Plan of the chapter: section 2 is devoted to overview the historical developments

i

n morpholo

gy

precedin

g

the lexicalist approach in

g

enerative lin

g

uistics. In section

3, we describe the characteristics of the notion of Lexicon in the early days of

g

enerative linguistics. Section 4 examines in detail the two seminal works in the

l

exicalist framework, namely Halle (1973) and Aronoff (1976). Then (section 5),

s

ome of the most important enhancements to the lexicalist approach are briefly

i

llustrated. In section 6, we return to the notion of Lexicon as it has been refined by

the lexicalist tradition. Finally (sections 7 and 8), we discuss some ma

j

or problems

(

speciall

y

the relation between morpholo

gy

and s

y

ntax) that an up-to-date lexicalist

v

i

ew

ha

s

t

oco

nfr

o

nt

w

ith

.

2. A BRIEF HI

S

T

O

RY

In the organization of linguistic theory, morphology is an intermediate discipline

between phonology and syntax. Over the years, the relationship of morphology with

these two fields of research has changed substantially a good number of times.

In 1

9

th

century European comparative linguistics, morphology lay at the heart of

the reconstruction of the Indo-European languages (cf. Bopp 1816, to name but one,

who compared Sanskrit, Latin, Persian and the Germanic lan

g

ua

g

es b

y

lookin

g

almost exclusivel

y

at morpholo

g

ical phenomena).

Morpholo

gy

was also central in American structuralist lin

g

uistics, althou

g

h the

m

ain focus of research was on phonology. The major ‘discovery’ of the time, the

P

honemic Princi

p

l

e

,

could be easily extended to morphology giving rise to the well-

k

nown

p

arallelis

m

p

hon

e

:

p

honem

e

= mor

p

h

:

mor

p

heme

,

extensively used to study

allophonic and allomorphic variation. Morphology was always present in the

A

merican tradition either viewed as grammatical process (Sapir 1921), or as

arrangement of morphemes (Bloomfield 1933)

.

3

W

ith the advent of earl

y

Generative Grammar (Chomsk

y

1957), morpholo

gy

lost

r

elevance in the

g

eneral or

g

anization of theoretical lin

g

uistics. Within that

framework, the lexicon contained onl

y

simple words (idios

y

ncratic, arbitrar

y

si

g

ns);

n

either com

p

ounds nor derived words had a place there. The only location where

they could be constructed was the transformational component, which at the time

was the only theoretical device capable of expressing grammatical relations. Phrase

s

tructure rules and transformations were allowed to manipulate words and

morphemes, thus making superfluous ever

y additional specification to account for

r

r

3

Cf. the discussion of the different models existing at the time in Hockett

(

1954

)

. Cf. also the relevance

o

f morphological matters in classical anthologies, e.g. Joos (1957).

T

HE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WORD

-

FORMATION

149

t

h

es

tr

uc

t

u

r

eo

f

wo

r

ds.

At th

es

am

e

t

ime, all the possible variations in form th

a

t

w

ords and morphemes might show (allomorphy) were assigned to the phonological

c

omponent.

F

or instance

,

in Aspects (1965: 184) Chomsk

y

proposed to use ‘nominalization

t

ransformations’ to account for the relation between word-pairs such as

d

estro

y

/

dest

r

uction

claimin

g

that “phonolo

g

ical

ru

l

es w

ill

de

t

e

rmin

e

that

n

om+destro

y

beco

m

es

dest

r

uction

.

” Hence, the purely morphological relation

be

t

ween

destro

y

an

d

dest

r

uction

was at the time accounted for by a combination o

f

s

yntactic and phonologi

c

al o

p

erations. In addition,

i

nflectional morphology was

h

andled in a similar way: Chomsky & Halle (1968) analyzed both irregular an

d

r

egular inflected verb-forms like

sang

and

g

mended

, as

sing

+past and

g

g

mend

+past,

d

d

“

where past is a formative with an abst

r

a

c

t f

e

at

u

r

es

tr

uc

t

u

r

e

i

n

troduced by syntactic

r

ules”

(

1968: 11

)

.

A

t that time

,

4

g

enerative lin

g

uistics simpl

y

did not have adequate formal

m

echanisms for these phenomena: the theor

y

assumed no morpholo

g

ical rules at

all

.

5

However, transformations were not suited to explain morphological facts: they

h

ad been introduced to handle syntactic phenomena, i.e. totally productive,

t

ransparent and regular phenomena. Words, on the contrary, tend to be less regula

r

(

cf.

d

estro

y

ĺ

*

d

estroy-ation), and, sometimes, they undergo idiosyncratic

l

exicalization

(

cf.

t

r

ansmission

‘the action of transmitting’ vs.

t

r

ansmission

‘gearbox

o

f a car’); furthermore, most lexical processes are not full

y

productive (cf.

read

ĺ

*

read

-

ation

).

A

few

y

ears later, Chomsk

y

’s Remarks on Nominalizations

(

cf. Roe

p

er, this

v

olume) suggested that these facts could be better explained by lexical rules: “Fairly

i

diosyncratic morphological rules w

i

ll determine the phonological form of

r

efus

e

,

d

estro

y

,

etc., when these items a

pp

ea

r

i

n the noun position” (Chomsky 1970: 271).

4

A summar

y

of the situation of morpholo

g

ical theor

y

in the be

g

innin

g

s of Generative Grammar is

g

iven

i

n Anderson

(

1988: 147

)

:

“

In American structuralist terms, the enterprise

o

f morphology can be divided into the study of

m

orphotactics (the arrangement of morphological elements into larger structures) and allomorphy

(variations in the shape of the ‘same’ unit). Early generative views, typified by Chomsky (1957) or

L

ees (1960) assigned the arrangement of all items into larger constructions to the syntax, whether the

s

tr

uc

t

u

r

es

in

vo

l

ved we

r

e

a

bove o

r

be

l

ow

th

e

l

eve

l

o

f th

ewo

r

d

–

w

hi

c

h

e

f

f

ectively eliminated the

f

f

independent study of morphotactics. The program

of classical generative phonology, on the other

m

h

and, as summed up in Chomsk

y

& Halle (1968), was

t

o reduce all variation in shape of unitar

y

l

in

g

uistic elements to a common base form as thi

s

mi

g

ht be affected b

y

a set of phonolo

g

ical rules –

which effectivel

y

reduced the stud

y

of allomorph

y

to the listin

g

of arbitrar

y

suppletions. With nothin

g

o

f substance left to do in morphology, genera

t

ive linguists had to be either phonologists o

r

syntacticians.”

5

In the major ‘readings’ that made the history o

f

Generative Grammar (e.g. Fodor & Katz 1964, Bierwish

&

Heidol

p

h 1970, Jacobs & Rosenb

a

um 1970, Reibel & Shane 1969, Gross, Halle & Schuetzenberger

aa

1973) there are no more than three to four articles on morphology and, crucially, they all treat purely

m

orphological phenomena transformationally (exceptions exist, e.g. Kiefer (1973)). Another famous

r

eader (Peters 1972) had the significant title Goals of Linguistic Theor

y

(with contributions by

l

inguists such as Fillmore, Chomsky, Postal, Kipa

r

sky, etc.): the volume contains only papers on

syntax and phonology, thus showing that at the ti

m

e

morphology was not even considered among the

‘

goals’ of linguistic theory.

1

50

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E & EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

AR

A

Linguists gradually became convinced that

rules different from transformations

t

s

hould o

p

erate in the lexicon to form com

p

lex words

.

6

2

.1 Lees

(

1960

)

B

efore going into the details of the lexicalist approach to morphology, let us

briefl

y

consider the kind of problems that

e

arl

yg

enerative theor

y

had to face. The

m

ost exhaustive treatment of morpholo

g

ical phenomena (specificall

y

of nominal

c

ompounds) within a transformational framework is that of Lees (1960).

L

ees accounts for the formation of compound words by applying transformations

to sentences. The arguments in support of this proposal are essentially of a semantic

and syntactic nature, and can be summarized in the following three points:

(

a) Nominal compounds are generated by transformations from underlying sentence

s

tructures in which the grammatical relations (subject, object, cf. p. 119) that

h

old implicitly between the two forma

t

ives of the com

p

ound are ex

p

ressed

explicitly.

(

b) If the meaning of a compound is ambiguous, it is possible to show that this

ambiguity results from different underlying sentences corresponding to the

different meanin

g

s. For instance, the ambi

g

uit

y

of a compound such as

snake

poison can be explained in “

g

rammatical” terms b

y

derivin

g

the different

m

eanin

g

s from (at least) th

r

ee different sentences

(

a. X extracts poison

f

rom the

snake

,

b.

T

he snake has the

p

oison

,

c. The poison is for the snak

e

).

(

c

)

Transformations can account for the intuition that com

p

ounds such as

windmill

an

d

flour mill

express different grammatical relations despite their superficial

l

s

imilarity (both compounds are of the N+N type): they are derived from different

deep structures (a. Wind powers the mill

,

b.

T

he mill grinds the flour

).

T

he ma

j

or problem arising from Lees’s proposal is that it requires a good deal of

deletion transformations which are too powerful

.

7

For example, to for

m

windmill

from the underlying sentence

wind powers the mill

it is necessary to delete the verb

l

power

,

while to derive the compound

car thief

, it is necessary to delete the verb

f

f

steal

(

assumin

g

that the deep structure of the compound is the sentence the thie

f

steals the

car

). In other words, Lees’s transformations require the deletion of lin

g

uistic

material that cannot be independently said

to have been ther

e in the first

p

lace.

Subsequent developments in generative

l

inguistics made an effort to exclude

unconstrained rules such as these from the g

r

ammar. It was already clear, by the mid

1960’s – with the influence of Chomsky’s (1965) principle of

R

ecoverability of

T

ransformations – that this type of unrestricted operations could not bring us close

r

to an adequate characterization of the notion ‘natural language’. Even if it were

possible to formulate the transformations required in the derivation of compounds in

s

uch a wa

y

as to satisf

y

the recoverabilit

y

principle, it would nevertheless be

n

ecessar

y

to postulate at least as man

y

transformations as the number of verbs that

6

Cf. Wasow

(

1977

)

and the comments thereof in Anderson

(

1977

)

.

7

A detailed discussion of this topic can be

f

ound in Allen (1978) and Scalise (1984), among others.

ff

T

HE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WORD

-

FORMATION

151

could be deleted, thus assuming rules of ‘

power

‘

deletion’, ‘

r

steal

deletion’, etc. These

l

t

ransformations are clearly

ad hoc

(

each of them is constructed to account for one

example) and their number cannot be const

r

ained; in this respect, Lees’s proposal

fails to achieve a satisfactor

y

level of descriptive adequac

y

.

3. THE LEXI

CO

N

Th

e

n

o

ti

o

n

o

f L

exicon

in Generative Grammar has

g

one throu

g

h a complex

p

rocess of develo

p

ment, from a Bloomfieldian conce

p

tion

(

the lexicon is “a list of

i

rregularities”, idiosyncratic

s

ound-meaning pairings) to a

m

ore articulated vision

,

where besides irregularities, the Lexicon contains also regular processes

.

8

In

S

yntactic Structures (Chomsky 1957), the Lexicon was not regarded as an

autonomous component of the grammar: the rules introducing lexical items were the

l

ast rules of the categorial component. Thus, the categorial component had only one

ty

pe of rule both for expandin

g

cate

g

orial s

y

mbols (e.

g

. 1.i, 1.ii) and for introducin

g

l

exical items (e.

g

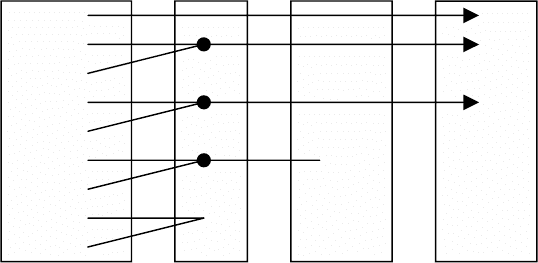

. 1.v-vii):

(

1

)

i. S

ĺ

NP + Aux +

V

P

ii

.

NP

ĺ

D

e

t + N

iii.

V

P

ĺ

V

+ NP

i

v.

A

u

x

ĺ

pres., past

v.

D

e

t

.

ĺ

th

e…

v

i

.

N

ĺ

g

irl, book ...

vii.

V

ĺ

take

,

read

,

walk …

F

urthermore, only simple words (or, better, morphemes) could be inserted by

suc

h r

u

l

es.

The most important modification of the framework (as far as morpholo

gy

is

c

oncerned, and in

p

articular for the lexicalist a

pp

roach

)

was the se

p

aration of the

L

exicon from the rewritin

g

rules proposed in Aspects. This move permitted a

significant simplification of the grammar since many of the properties of lexical

formatives are, in fact, irrelevant to the functioning of the base rules and,

furthermore, are often idiosyncratic. For exam

ple, the fact that there are two classes

m

m

o

f transitive verbs, those that allow deletion of the ob

j

ect (e.g.

to read

) and those

dd

t

hat do not (e.g. to bu

y

), no longer had to be handled by rewriting rules. Instead, the

properties of verbs such as

read

and

d

b

u

y

could be specified in their lexical entries.

The or

g

anization of the lexicon presented in Aspects can be considered a ma

j

or step

i

nto the direction of what we call toda

y

Lexicalism: in order to simplif

y

the s

y

ste

m

o

f base rules, the Lexicon was

g

iven a

g

reater importance (and wei

g

ht) in the theor

y

.

I

n Chomsky’s As

p

ects

,

atomic category symbols wer

e

subcategorized by feature

m

atrices

(

sets of attribute-value

p

airs

)

i

n

w

hi

c

h

v

ari

ous

kin

ds o

f inf

o

rmati

o

n

we

r

e

encoded. Two types of feature matrices were used. The first was a system of

i

nherent features describing lexical entries (cf. (2)):

8

F

o

r a

c

l

e

ar

d

iff

e

r

e

ntiati

o

n

be

t

wee

n th

ese

t

wo

c

onceptions of the lexicon, cf. Aronoff (1989).

1

52

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

E

MILIAN

OGU

E

V

ARA

T

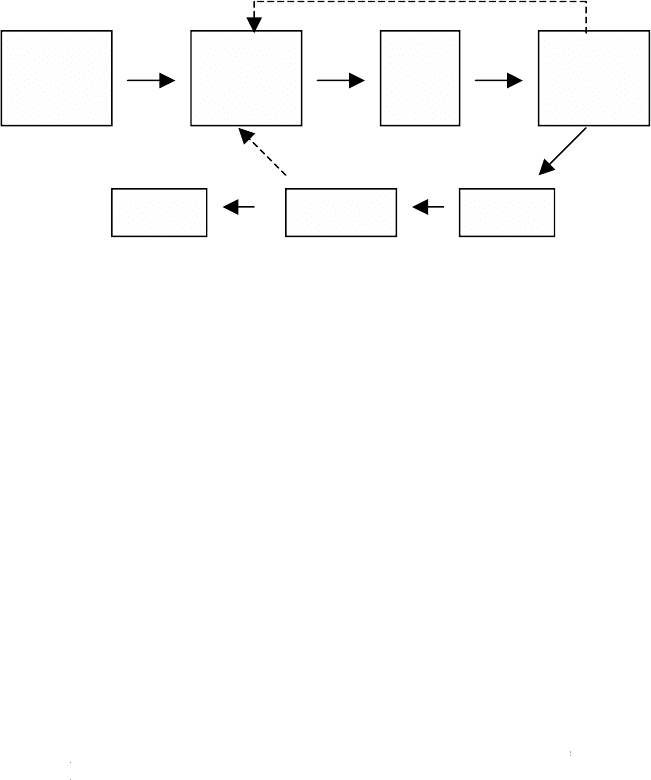

he second type of subcategorization consisted in a system of contextual features

that specified the syntactic environment i

n

which a given lexical entry can appea

r

(

so-called strict subcategorization frames).

C

onsider the contextual features that

c

haracterize the following verbs:

Th

e

inf

o

rmati

o

n a

ssoc

iat

ed w

ith a

l

exical item (lexical cate

g

or

y

an

d

s

ubcate

g

orization frames) is crucial for the explanation of the morpholo

g

ical

phenomena in an

y

lan

g

ua

g

e: morpholo

g

ical rules use this information to select the

bases to which they may apply. For a br

i

ef illustration, consider the following nouns,

with each one being able to appear only w

i

th certain derivational suffixes

,

but not

w

ith all

o

f th

e

m

:

(

4

)

-ian -hood -(i)fy

C

homsky + – – = Chomskyan

boy – + – = boyhood

beauty – – + = beautify

(

3

)

eat

[+__NP ]

t

John eats food

.

seem

[+__Adjective, +__

like

-

Predicate-Nominal

]

John seems sad. John seems like a nice fellow.

grow

[+

__

NP, +

__

#, +

__

Ad

j

ective ]

John

g

rew a beard. John

g

rew. John

g

rew sad.

(

2

)

CO

MM

O

N

+ –

C

O

U

NT

A

NIMAT

E

+– +

–

A

N

IMATE AB

S

TRA

CT

HU

MAN

E

gyp

t

+

–

+ – +

–

H

U

MAN

book

vi

r

tue

di

r

t

Fr

eud

F

ido

+

–

bo

y

d

og

boy = [+common, +count, +animate, +human]

Egypt = [–common, –animate], etc.

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WORD

-

FORMATION

153

Th

esu

ffix -

ian

can only attach to [–common] nouns (cf.

E

gyptian

,*

table

-

ian

,

*

ho

r

se

-

ian

)

, whereas -(i)f

y

attaches to nouns subcategorized as [+common,

±

abstract, –animate]

(

cf. countrif

y

,*

E

ngland-if

y

,*

s

ecretar-if

y

,*

hors-if

y

). Finally,

-

hood

selects [+common, –abstract, +animate] nouns (cf.

d

neighborhood

,

priesthood

,

*

democracy-hood

,*

correction-hood

, *

George-hood

).

dd

Moreover, strict subcate

g

orization frames are also relevant for derivation, as it is

o

ften the case with deverbal derivation. For instance

,

the suffix

-able

attaches b

y

r

ule to verbs characterized as [+

__

NP] (i.e. transitive verbs):

eatable

,

believable

bu

t

*

seemable

.

T

he notion of lexicon

p

resented in

A

s

p

ects was yet a static one: it served the sole

function of providing the syntax with words. Chomsky informally suggested that “it

m

ay be necessary to extend the theory of lexicon to permit some ‘internal

c

omputation’” (Chomsky 1965: 187). As we w

i

ll see, in later work, (e.g. Chomsky

1970, Halle 1973, Jackendoff 1975, Aronoff 1976

)

the Lexicon is much more than a

s

imple list of words: besides a list of underived lexical entries and idios

y

ncratic

c

omplex units, it also contains an explicit internal computation, the word formation

c

om

p

onent.

4

. LEXI

C

ALI

S

M

A

s it has been pointed out above, Chomsky’s

R

emarks on

N

ominalization

i

nitiated a totally different perspective

o

n morphological phenome

n

a, suggesting that

at least some complex words are better

e

xplained as lexical formations than as

t

ransformations: derived complex words are built in the Lexicon, inflected complex

words are

g

enerated b

y

s

y

ntactic transformations (cf. Roeper, this volume). This

i

dea laid the foundations for a more d

y

namic view of the Lexicon.

R

emarks on Nominalization represented a definitive turnin

g

point in the stud

y

of

m

orphology; its consequences greatly exceeded what could be imagined at the time.

C

homsky treated only deverbal nominalizations but, quite clearly, the lexicalist

explanation could be argued for many ot

her derivational processes: deverbal

t

ad

j

ectives (

readable

,

att

r

active

), dead

j

ectival nouns (

r

eadabilit

y

,

att

r

activeness

)

etc.

(

cf. Carstairs-McCarthy 1992: 17–19). In the following sections we will provide an

o

verview of some of the most influential developments in the lexicalist approach. In

particular, those which had the most profound impact on the architecture of the

g

rammar

.

4

.1 Halle

(

1973

)

T

he linguist who was first able to draw the logical conclusions from the

c

riticisms that were being raised against the transformational treatment of word

f

o

rmati

o

n

w

a

s

M

o

rri

s

Hall

e.

In hi

s

arti

c

l

e

P

rolegomena to a Theory of Word

F

o

r

mation

,

Halle advanced the first proposal of an autonomous morpholo

g

ical

c

omponent within the framework of the Lexicalist theor

y

. This work, althou

g

h

154

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

ARA

r

elatively short and programmatic, has ser

v

ed as the foundation and ins

p

iration fo

r

muc

h

wo

rk in l

e

xi

c

ali

s

m

.

H

alle’s starting point is the idea that if a grammar is a formal representation of a

n

ative speaker’s knowledge of language, then there must be a component that

accounts for the speaker’s lexical knowledge: a speaker of English ‘knows’, fo

r

example, a) that

read

is a word of his/her language, but

d

le

z

en

is not, b

)

that certain

w

ords have internal structure (e.

g

.

un

-

d

r

ink

-

able

)

and c

)

that the internal structure

r

espects a specific order of c

o

ncatenation of morphemes (

un

-

d

r

ink

-

able

is a possible

wo

r

dbu

t

*

un-able-drink

or *

k

d

r

ink

-

un

-

able

are not). Such knowled

g

e can be

r

e

p

resented in a formal model:

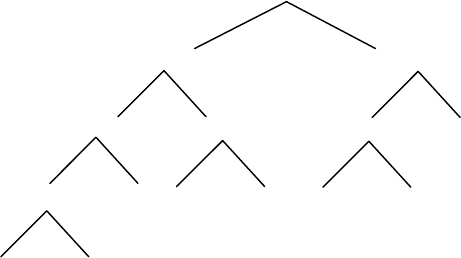

F

i

g

ure 1

Let us briefl

y

examine how this model works. In Halle’s view, the basic units of

t

he lexicon are mor

p

hemes. Each mor

p

heme is re

p

resented as a se

q

uence of

phonological segments provided with a syntactic label (N, V, etc.), except affixes,

which are labeled Af (without syntactic category):

(

5

)

[home]

N

[

arrive

]

V

[

-al

]

A

f

These forms constitute the in

p

ut of

W

ord Formation Rules

,

which are

responsible for the sequential arrangement

of the morphemes of a language into

t

actual words. WFRs can freely apply to the list of morphemes, forming potential

words (i.e. words that are not listed in the Dictionary). WFRs are of two types, those

t

hat apply to stems and those that apply to words:

(

6

)

a. [STEM + Af ]

A

t

o

t+

al

b. [VERB + Af

]

N

arri

v

+

al

W

FRs can change not only the lexical category of the input lexical item, but also

t

he s

y

ntactic features associated with it. For example, the suffix

-hood

can attach to

d

[

–abstract] Nouns resultin

g

i

n [+abstract] Nouns

(

b

o

y

ĺ

boyhood

,

p

ries

t

ĺ

priesthood

).

d

d

L

i

s

t

of

Mor

p

hemes

W

ord

Fo

rmati

on

R

u

l

es

Filt

e

r

Di

ct

i

onary

o

f

W

ords

O

ut

p

ut Phonolog

y

Synta

x

THE LEXICALIST APPROACH TO WOR

D

-

F

ORMATION

155

Halle’s model of morphology entails a more radical version of the L

exicalist

H

ypothesis than was originally proposed in Chomsky (1970): Halle’s WFRs operate

i

n the same way for derivation and inflectio

n

9

(compounding was not yet in the

picture at the time), both derivational and inflectional affixes are equall

y

listed in the

L

exicon. The motivation for this choice is that the set of morphophonolo

g

ical

operations and the idiosyncratic behavior

typical of derivational processes has

r

p

arallels in inflection.

The third subcom

p

onent in Halle’s model is the F

ilte

r

.

The Filter has basically

t

wo functions: a) it adds idiosyncratic features when necessary (e.g. a word such as

recital

is formed regularly as is

l

a

rr

ival

,

but the Filter gives it its idiosyncratic

m

eaning “performance of a soloist”) and b) it prevents possible but non-existing

words (e.g.

*

i

gnoration) from appearing in sentences by assigning the feature [

–

l

exical insertion

]

to them.

The final subcom

p

onent in Halle’s model is the

D

ictionar

y

,

which is entirel

y

determined b

y

the interaction of the List of Morphemes, WFRs and the Filter: it

c

ontains all existing words, including all

t

h

e

infl

ec

t

ed

f

o

rm

s

o

f every word. The

w

h

o

l

e

m

ec

hani

s

m

c

an

be su

mmarized with the following schema:

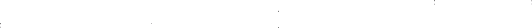

List of morphemes WFRs Filter Dictionary

Figure 2

Halle’s proposal represented a fundamental step in the development of the theory

o

f morphology: for the first time it was proposed to handle all morphological

phenomena in a single place (i.e. the Lexi

c

on) and by means of specific rules

(WFRs). This suggestion served not only to lighten the burden of the

t

ransformational component b

y

removin

g

t

hose operations that involved numerous

l

exicall

yg

overned exceptions: it also provided a wa

y

to account for a fundamental

difference between syntax and morphology. The notion “possible but non-existent

9

Halle’s position is today called

S

trong Lexicalist Hypothesis as o

pp

osed to the so-called Weak Lexicalis

t

Hy

pothesis

(

where derivational and inflec

t

ional morpholo

gy

are handled b

y

different sets of rules).

C

f. section 5.1 below.

1.

f

r

i

en

d

2. boy

-h

ood

3

.

r

ec

it

e

-al

4

. i

g

nore

-ati

o

n

5.

m

ou

ntain

-

a

l

X

[

+idios

y

n]

X

[– L. I.]

156

S

ER

G

I

OSC

ALI

S

E

&

EMILIAN

OGU

E

V

ARA

word” became crucial for morphology; a parall

e

l

concept is totally absent in syntax,

where in fact, it makes no sense to say that a sentence is ‘possible but non-existent’.

W

ith respect to earlier models of morphology, such as the

I

tem and Arrangemen

t

mode

l

1

0

that

j

oined morphemes by the simple operation of concatenation, Halle’s

proposal represented a significant innovation in that it contains a special mechanis

m

for creating complex words (i.e. WFRs), a m

ec

hani

s

m that mak

es use o

f m

o

r

e

l

in

g

uistic information and carries out more abstract operations than simple

co

n

c

at

e

nati

o

n

.

To see wh

y

concatenation is not an ad

e

quate wa

y

to explain word formation,

co

n

s

i

de

r th

e

Fr

e

n

c

h

wo

r

d

rest

r

uctu

r

ation

‘restructuring’: this word cannot simply be

built up by concatenation of the three morphemes

re

+

st

r

uctu

r+

ation

;

it must have

i

nternal structure since it is not

p

ossible to

attach just any pref

ix or suffix to any

f

f

base. That is, the prefix

re-

must be attached to verbs, not to nouns

(

cf.

*

re

-

ve

r

ité

‘re-truth’) or adjectives (cf.

*

re-grand

‘re-great’), and the suffix

d

-

ation

m

us

t al

so be

attached to verbs, not to nouns

(

cf.

*

v

erity-ation ‘truth-ation’) or adjectives (cf.

*

g

rand-ation ‘

g

reat-ation’). Thus the base of the derived word

rest

r

uctu

r

ation

m

us

t

be a verb

(

s

tructur

(

er

)

‘to structure’

)

and the derivation must be carried out in two

s

te

p

s: i.

s

tructur

(

er

)

ĺ

r

e-structur

(

er

)

,

ii.

r

estructur

(

er

)

ĺ

r

est

r

uctu

r-

ation

.

Th

us

the word in question has the following internal structure:

(

7

)

[[re+[structur]

V

]

V

+ation

]

N

I

t should be remembered that Halle’s main

p

ur

p

ose was to stimulate discussion

i

n a still neglected field. We can see today that this goal has, in fact, been completely

achieved although later research on morphology has raised questions on every

subpart of the model seen above.

Placing morphemes at the base of the s

y

s

tem is a problematic choice because,

while in English simple words and morphemes coincide most of the time, this is not

alwa

y

s the case with other lan

g

ua

g

es. Moreover, considerin

g

derivational and

i

nflectional affixes as included in the List of Morphemes obscures the difference

between the formation of new words (or ‘lexemes’, e.

g

.

w

r

it

+

er

from

r

w

r

ite

)

and the

formation of word-forms (e.g.

w

r

ite

+

s

,

writ+in

g

).

Halle’s WFRs are

q

uite unrestricted; no

t

only do they have access to information

t

contained in later stages in a derivation (t

he Dictionary), but they also generate a

t

l

arge number of ungrammatical forms

.

Finally, also the Filter has been criticized, mainly because it is not a finite

m

echanism. The set of possible but non-existent words is not finite in the sense that

there are no

g

rammatical principles restrictin

g

the de

g

ree of complexit

y

of derived

and compound words, with the likel

y

exception of performance considerations such

as memor

y

(cf. Booi

j

1977).

10

Cf. Hocket

(

1954

)

.