Suny R.G. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 3: The Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

archie brown

Soviet troops was intended by their chiefs in the power ministries to be but the

beginning of a more general crackdown on all fissiparous movements. They

also hoped to separate Gorbachev from the most liberal-minded members

of his team and from the democratic movement that had developed after

1989 in Russian society. In the latter aim in particular the conservatives had

some success. Yet – in contrast with the sustained violence in Chechnya in

post-Soviet Russia – each incident in which force was used in the Gorbachev

era was a one-day event. The forces favouring violent suppression of national

and separatist movements were never given their head to ‘finish the job’,

partly because of Gorbachev’s reluctance on moral grounds to shed blood and

partly because he realised that such violence as had been applied was entirely

counter-productive.

Separatist movements in the Soviet Union were given a huge impetus by

developments in Eastern Europe in 1989. It was at this point that the radicali-

sation of the political agenda came full circle. Developments within the Soviet

Union itself had been the key to change in the rest of Communist Europe.

The peoples of Central and Eastern Europe had decided to test the sincerity

of Gorbachev’s professed willingness to let the people of each country decide

for themselves the character of their political system. They could not fail to

notice that, to their surprise, domestic liberalisation had gone further by the

end of 1988 within Russia than it had in most of the Warsaw Pact countries.

The outcome of taking Gorbachev at his word was that in the course of one

year Eastern European countries became non-Communist and independent.

For Estonians, Latvians and Lithuanians, this was especially significant. They

were no longer ready to argue simply for greater sovereignty within a renewed

Soviet Union but for an independent statehood that would be no less than that

enjoyed by Czechs, Hungarians and Poles.

53

Moreover, competitive elections

had brought to the fore politicians – including, in the case of Lithuania, even

the Communist Party first secretary (Algirdas-Mikolas Brazauskas) – ready to

embrace the national cause.

When Gorbachev had declared each people’s ‘right to choose’, he had in

mind existing states. He truly believed that there was a ‘Soviet people’ who

had a lot in common which transcended national differences. His doctrine

of liberation was not intended to lead to separatism in the USSR. When he

came round to recognising the reality of the Soviet Union’s own ‘nationality

problem’, his preferred solution was to turn pseudo-federation into genuine

53 Archie Brown, ‘TransnationalInfluences inthe Transition from Communism’, Post-Soviet

Affairs 16, 2 (Apr.–June 2000): 177–200.

346

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Gorbachev era

federation – even, as a last resort, in late 1991 into a loose confederation. In April

1991 Gorbachev initiated a new attempt to negotiate a Union Treaty that would

preserve a renamed Union on a voluntary basis. Only nine out of the fifteen

republics participated in the talks. The fact that they went ahead regardless

reflected the fact that Gorbachev and the liberal wing of the leadership (people

such as Yakovlev, Shakhnazarov and Cherniaev) had come to accept de facto

that the Union would not consist of as many as fifteen republics in the future.

They wished, however, that secession, where it had become a political necessity,

would be orderly and legally defined.

Events conspired against the preservation of even a smaller union. The

election of Yeltsin as Russian president in June 1991 gave him a legitimacy

to speak for Russia that was now greater than that of Gorbachev, who had

been only indirectly elected by a legislature representing the whole of the

USSR more than a year earlier. For some time Yeltsin had been pressing for

Russian sovereignty within the Union. In May 1990 he insisted that Russian law

had supremacy over Union law. This was a massive blow against a federalist

solution to the problems of the Union.

54

The same claim had been made on

behalf of Estonia, but Russia contained three-quarters of the territory of the

USSR and just over half of its population, so the threat to the future of a

federal union was of a different order. Nevertheless, by the summer of 1991,

the nine plus one negotiations had produced a draft agreement which Yeltsin

and the Ukrainian president, Leonid Kravchuk, were prepared to sign. The

president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbaev, at that time a strong supporter

of preserving a Union, played a constructive role in securing the agreement.

55

Gorbachev had made many concessions. A vast amount of power was to be

devolved to the republics, so much so that the conservative majority within

the CPSU apparatus, the army and the KGB were convinced that this would

be but a stepping-stone to the break-up of the Soviet Union.

Thus, with the draft Union Treaty due to be signed on 20 August 1991,

and with Gorbachev preparing to fly back to Moscow from his holiday home

in Foros on the Crimean coast, the final blow to the Union was struck by

people whose main aim was to preserve it. Gorbachev, his wife and family

and one or two close colleagues (including Cherniaev) were put under house

arrest on 18 August and a state of emergency was declared in Moscow early

in the morning of 19 August. A self-appointed State Committee for the State

of Emergency was set up in which the Soviet vice-president, Gennadii Ianaev,

54 See Aron, Boris Yeltsin,p.377.

55 Georgii Shakhnazarov, Tsena svobody: Reformatsiia Gorbacheva glazami ego pomoshchnika

(Moscow: Rossika Zevs, 1993), p. 233.

347

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

archie brown

had been persuaded to play the most public role. In order to provide a fig leaf

of legality, the plan had been to persuade Gorbachev to hand over his powers

(temporarily, he was told) to the vice-president.

From the moment that Gorbachev denounced the delegation which had

been sent to cajole or intimidate him into acquiescing with their action (which

had begun with cutting off all his telephones) the putschists were in trou-

ble.

56

The key figures in this attempt to turn the clock back (which, if it had

succeeded, would logically have resulted in severe repression in the most dis-

affected republics and a return to a highly authoritarian regime in the Soviet

Union as a whole) were, unsurprisingly, the chairman of the KGB, Vladimir

Kriuchkov, the powerful head of the military-industrial complex of the Soviet

Union, Oleg Baklanov, and the minister of defence, Dmitrii Iazov. Many senior

Communist Party officials sympathised with them and one Politburo member,

Oleg Shenin, was intimately involved in the coup attempt. Because, however,

the CPSU had by this time lost whatever prestige it once enjoyed, the emphasis

of the plotters was on patriotism and preserving the Soviet state. There was no

reference to restoring the monopoly of power of the Communist Party or to

Marxism-Leninism. Many people demonstrated in Moscow against the coup,

but throughout the country as a whole most citizens waited to see who would

come out on top. Many republican and most regional party leaders assumed

that those who had taken such drastic action would prevail and hastened to

acknowledge the ‘new leadership’.

It emerged, however, that even the most conservative section of the Soviet

party and state establishment had been affected by the changes in Soviet society

and the new norms that had come to prevail over the previous six and a half

years. Yeltsin, in the Russian White House (the home at that time of the Russian

government), became the symbol of resistance to the coup. He received strong

support from Western leaders, although a few had initially been prepared to

accept the coup as a fait accompli, among them President Mitterrand of France.

The tens of thousands of Muscovites (several hundred thousand over several

days when account is taken of comings and goings) who surrounded the White

House raised the political cost of its storming, but would not have prevented

the building and its occupants being seized, if the army, Ministry of Interior

and KGB troops had acted with the kind of ruthlessness they displayed in

56 On the coup, see Mikhail Gorbachev, The August Coup: The Truth and the Lessons (London:

HarperCollins, 1991); Anatoly Chernyaev, My Six Years with Gorbachev, trans. and ed.

Robert English and Elizabeth Tucker (University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University

Press, 2000), esp. ‘Afterword to the U.S. Edition’, pp. 401–23; and V. Stepankov and E.

Lisov, Kremlevskii zagovor: Versiia sledstviia (Moscow: Ogonek, 1992).

348

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Gorbachev era

pre-perestroika times. Yet, faced with political resistance, the forces of coercion

themselves became divided. Since the coup leaders were people who had for

several years been denouncing Gorbachev – at first, in private, and of late in

public – for ‘indecisiveness’, it is ironic that their own indecision made certain

the failure of the coup. They lacked the resolution to carry it to its logical

conclusion and gave up the attempt as early as 21 August.

The putsch was, however, a mortal blow both for the Union and for the

leadership of Gorbachev. Having seen how close they had been to being fully

reincorporated in a Soviet state whichwouldhave been a throwbacktothe past,

the Baltic states instantly declared their independence. This was recognised

by the Soviet Union on 6 September. Four days later Armenia followed suit,

while Georgia and Moldova already considered themselves to be independent.

While Gorbachev had been isolated on the Crimean coast, Yeltsin had been the

public face of resistance to the coup, and Gorbachev’s position became weaker

and Yeltsin’s stronger in its aftermath. Taking full advantage of this further shift

in the balance of power, Yeltsin was no longer content with the draft Union

Treaty that was to have been signed in August. New negotiations saw further

concessions from Gorbachev which would have moved what remained of a

Union into something akin to a loose confederation. Ultimately, this did not

satisfy the leaders of the three Slavic republics – Yeltsin, Leonid Kravchuk of

Ukraine, and Stanislav Shushkevich of Belarus. At a meeting on 8 December

1991 they announced that the Soviet Union was ceasing to exist and that they

were going to create in its place a Commonwealth of Independent States (see

Map 12.1). Not the least of the attractions of this outcome for Yeltsin was that

with no Union there would be no Gorbachev in the Kremlin. In the months

following the coup he had been sharing that historic headquarters of Russian

leaders with Gorbachev, but, given their rivalry, such a ‘dual tenancy’, like

‘dual power’ in 1917, could not last.

In a televised ‘Address to Soviet Citizens’ on 25 December 1991, just as the

Soviet state itself was coming to an end, Gorbachev announced that he was

ceasing to be president of the USSR. He said that, although he had favoured

sovereignty of the republics, he could not accept the complete dismemberment

of the Soviet Union and held that decisions of such magnitude should have

been accepted only if ratified by popular will. Looking back on his years in

power, he observed that all the changes had been carried through in sharp

struggle with ‘the old, obsolete and reactionary forces’ and had come up

against ‘our intolerance, low level of political culture and fear of change’. Yet,

he could justly claim that the society ‘had been freed politically and spiritually’,

with the establishment of free elections, freedom of the press and freedom of

349

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

0

0

300 km

300 miles

Istanbul

˙

Rostov

Krasnodar

Astrakhan’

Volgograd

Saratov

V

o

l

g

a

Penza

Voronezh

Tula

Ryazan’

Moscow

Yaroslavl’

V

o

l

g

a

Nizhnii

Novgorod

Kazan’

Izhevsk

Ufa

Orenburg

U

r

a

l

Oral

(Ural’sk)

Perm’

Ekaterinburg

Cheliabinsk

Atyrau

Aqtau¯

(Aktau)

Makhachkala

Beyneu¯

(Beyneu)

Türkmenbashy

TURKMENISTAN

A

m

u

r

Petropavlovsk

Aqtöbe

(Aktyubinsk)

Aral

(Aral’sk)

Ustyurt

Plateau

Nukus

Dashhowuz

Turkmenabat

(Chärjew)

Ashgabat

D

a

r

y

a

Mashhad

Mary

Hera¯t

AFGHANISTAN

IRAN

PAKISTAN

INDIA

Kabul

Tehra¯n

Diyarbakir

Baghdad

IRAQ

T

i

g

r

i

s

Amman

Jerusalem

SYRIA

Damascus

Beirut

Nicosia

ISRAEL

LEBANON

JORDAN

CYPRUS

TURKEY

Tabrı¯z

AZERBAIJAN

Baku

Sumgait

Erevan

ARMENIA

T’bilisi

GEORGIA

Bat’umi

Sokhumi

Groznyi

Aleppo

E

u

p

h

r

a

t

e

s

Adana

Mediterranean

Sea

Bursa

Konya

Ankara

Samsun

T

A

U

R

U

S

M

T

S

D

O

G

U

K

A

R

A

D

E

N

I

Z

D

A

G

L

A

R

I

Black Sea

Constanta

Sevastopol’

BULGARIA

ROMANIA

Bucharest

D

a

n

u

b

e

UKRAINE

Sea of

Azov

POLAND

Warsaw

Vilnius

Chernivtsy

Chis˛ina˘u

Kiev

L’viv

Rivne

MOLDOVA

Chernobyl’

Homyel’

BELARUS

Brest

Kaliningrad

RUSSIA

V

i

s

t

u

l

a

Minsk

Vitebsk

D

n

ep

r

LITHUANIA

Rı¯ga

LATVIA

Tallinn

St Petersburg

ESTONIA

SWEDEN

Stockholm

Baltic

Sea

FINLAND

Helsinki

G

u

l

f

o

f

F

i

n

l

a

n

d

Lake

Ladoga

Lake

Onega

White

Sea

Arkhangel’sk

Pechora

O

b

’

P

e

c

h

o

r

a

CA

R

P

A

T

H

I

A

N

M

T

S

Mariupol’

D

o

n

Odessa

Dnipropetrovsk’

Volga Don

Canal

Samara

Tol’yatti

Kuibyshevskoe

Vodokhranilishche

K

a

m

a

U

R

A

L

M

O

U

N

T

A

I

N

S

Mykolayiv

Kryvyy Rih

Donets’k

Zaporizhzhia

D

o

n

Khar’kiv

CA

S

P

I

A

N

D

E

P

R

E

S

S

I

O

N

Caspian

Sea

(lowest point

in Europe

–28m)

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

.

(highest point

in Europe 5633m.)

Gora El’brus

S

e

v

e

r

n

a

i

a

D

v

i

n

a

Su

k

h

o

n

a

Rybinskoe

Vodokhranilishche

Volg

a

Omsk

Pavlodar

Astana

Qostanay

(Kostanay)

TORGHAY

U

¯

STIRTI

Novosibirsk

Ob’

I

r

t

y

s

h

RUSSIA

Z

h

a

y

y

q

E

n

i

s

e

i

Kemerovo

Novokuznetsk

Barnaul

K

a

t

u

n

B

i

y

a

E

r

t

i

s

Qaraghandy

(Karaganda)

Semey

(Semipalatinsk)

Öskemen

(Ust’-Kamenogorsk)

Lake Balkhash

Almaty

Balqash

(Balkhash)

Saryshaghan

(Saryshagan)

Qyzylorda

(Kyzylorda)

Taraz

Shymkent

Tashkent

Samarqand

Bukhara

Dushanbe

G

A

R

A

G

U

M

K

O

P

PEH D

A

G

H

H

I

N

D

U

K

U

S

H

Isla¯ma¯ba

¯d

Osh

Q

I

Z

I

L

Q

UM

UZBEKISTAN

TAJIKISTAN

Kashi

CHINA

KYRGYZSTAN

Bishkek

Ysyk-Köl

T

I

E

N

S

H

A

N

TAKLA MAKAN

DESERT

Indian

claim

L

i

n

e

o

f

C

o

n

t

r

o

l

Chinese line

of control

I

n

d

u

s

K

A

RAK

O

R

A

M

R

A

N

G

E

P

A

M

I

R

S

H

I

M

A

L

A

YA

S

Andijon

Khujand

A

L

A

Y

M

T

S

Aral

Sea

Baikonur

Cosmodrome

KAZAKHSTAN

BETPAQDALA

Taldyqorghan

(Taldykorgan)

Krasnoiarsk

Hrodna

Ul’ianovsk

Vyc

h

e

g

d

a

E

L

’B

R

U

S

M

T

S

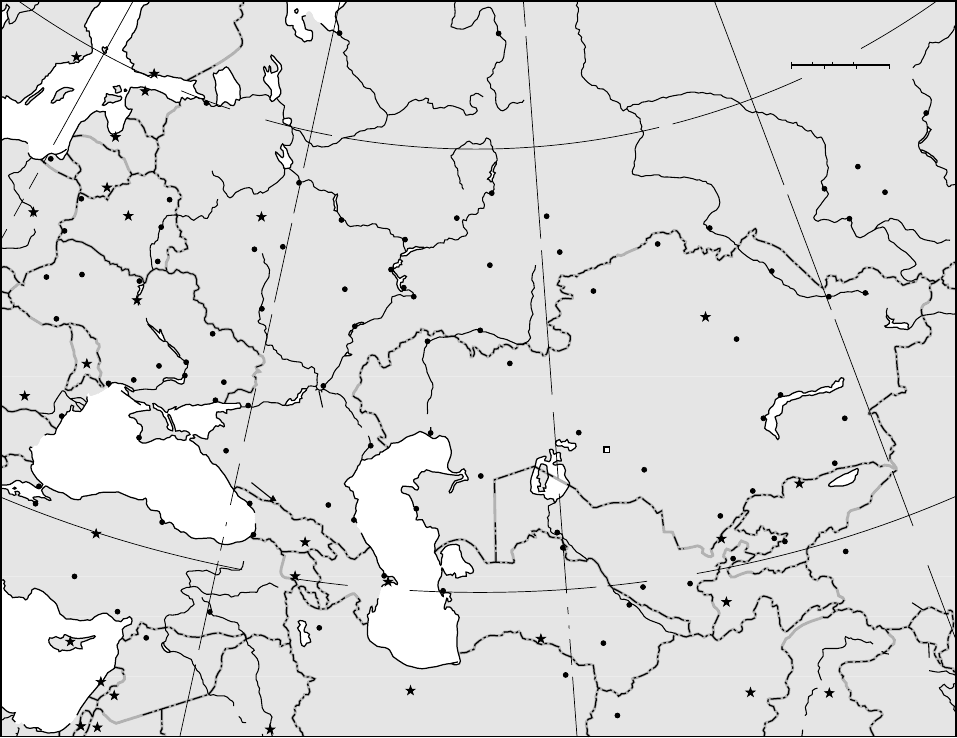

Map 12.1. Commonwealth of Independent States

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Gorbachev era

worship. On foreign policy the gains seemed to Gorbachev to be especially

clear:

An end has been put to the ‘Cold War’, the arms race and the insane mili-

tarisation of our country, which disfigured our economy, social thinking and

morals. The threat of world war has been removed.

Moreover:

We opened ourselves up to the rest of the world, renounced interference in

the affairs of others and the use of troops beyond our borders. In response,

we have gained trust, solidarity and respect.

Looking ahead, Gorbachev had words of warning:

I consider it vitally important to preserve the democratic achievements of

the last few years. We have earned them through the suffering of our entire

history and our tragic experience. We must not abandon them under any

circumstances or under any pretext. Otherwise, all our hopes for a better

future will be buried.

57

57 The full text of Gorbachev’s resignation speech is to be found in Mikhail Gorbachev,

Zhizn’ i reformy, vol. i,pp.5–8; and in the abbreviated English translation of that book:

Gorbachev, Memoirs (London: Transworld, 1996), pp. xxvi–xxix.

351

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

13

The Russian Federation

michael mc faul

The immediate afterglow of the failed coup attempt in August 1991 must rank

as one of the more optimistic periods in Russian history. In August 1991, like

many other times in Russia’s past, Kremlin rulers had issued orders to suppress

the people. This time around, some of the people resisted. For three days, a

military stand-off ensued between those defending elected representatives of

the people in the White House – the home to Russia’s Congress of People’s

Deputies – and those carrying out orders issued by non-elected leaders in

the Kremlin.

1

Popular resistance to the coup attempt was not widespread. In

fact, except for Moscow, St Petersburg and the industrial centres in the Urals,

there were no signs of resistance at all.

2

But this concentrated opposition,

especially in Moscow, produced major consequences for Russia’s history. In

this round of conflict between the Russian people and their rulers, the people

prevailed. The victory created an atmosphere of unlimited potential. One

Western publication declared, ‘Serfdom’s End: a thousand years of autocracy

are reversed’.

3

The triumph, however, also fuelled inflated expectations about what was to

come next. The victors immediately accomplished some symbolic gestures,

such as the arrest of the coup plotters and the destruction of Feliks Dzerzhin-

sky’s statue outside the KGB’s headquarters. But the bigger tasks of creating

a new state, economy and polity soon erased the euphoria of August 1991 for

Russia’s political leadership. Russian President Boris Yeltsin, the unquestioned

hero of the dramatic August events, most certainly seemed overwhelmed. He

spent three weeks in September outside Moscow on vacation.

1 The situation represented a classic revolutionary situation of dual sovereignty. See Charles

Tilly, From Mobilization to Revolution (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978), ch. 9.

2 For assessments of national resistance, see John Dunlop, TheRiseofRussiaandtheFallof

the Soviet Empire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993), pp. 236–7.

3 This title is from Time, 2 Sept. 1991,p.3.

352

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

0

0

800 km

800 miles

Komi

Tatar

2

Komi

23

58

17

Adygea 432

Bashkortostan 3,943

Buriatia 1,038

Chechnya and Ingushetia* 1,270

Chuvashia 1,338

Dagestan 1,802

Gorno-Altai

191

Kabardino-Balkaria 754

Kalmykia 323

Karachai-Cherkessia 414

Karelia 790

Khakassia 567

Komi 1,251

Mari El 750

Mordovia 963

North Ossetia 632

Tatarstan 3,642

Tuva 30

9

Udmurtia 1,606

Yakutia 1,094

Occupied by the

Soviet Union in 1945

administered by Russia,

claimed by Japan

Per cent of:

Other

Titular

Republic

Nationality

Russians

Source: 1989 Census.

Minor

Nationality

Udmurtia

Mari El

Chuvashia

Karelia

Mordovia

Adygea

Karachai-

Cherkessia

Kabardino-

Balkaria

North Ossetia

Chechnya*

Ingushetia*

Kalmykia

* At the time of the 1989 Census Chechnya and

Ingushetia were a single Soviet autonomous republic.

Population distribution between the two current

republics has not been determined.

Tatar

2

Yakut

33

50

15

Yakutia

Tatar

7

Udmurt

31

59

3

Tatar

6

Mari

43

48

3

Tatar

1

Karelian

10

74

15

Tatar

3

Chuvash

68

27

2

Tatar

5

Mordvinian

33

61

1

Cherkess

10

Karachai

31

42

17

Balkar

9

Kabardin

48

32

11

Tatar

1

Adygei

22

68

9

Ingush

5

Ossetian

53

30

12

Chechen

58

Dagestani

Peoples

80

Ingush

13

23

6

Dagestan

Bashkortostan

Tatarstan

Chechen

3

Dagestani

Peoples

6

Kalmyk

45

Tatar

49

Bashkir

22

4

43

Chuvash

4

39

11

38

9

8

Tatar

28

11

Gorno-Altai

Khakassia

Tuva

Buriatia

Tatar

1

Altay

31

60

8

8

Tatar

1

80

Khakass

1

32

3

Khakass

11

Tuvinian

64

Tatar

1

70

5

Buryat

24

Total Republic Population

(in thousands)

Republic

Russia

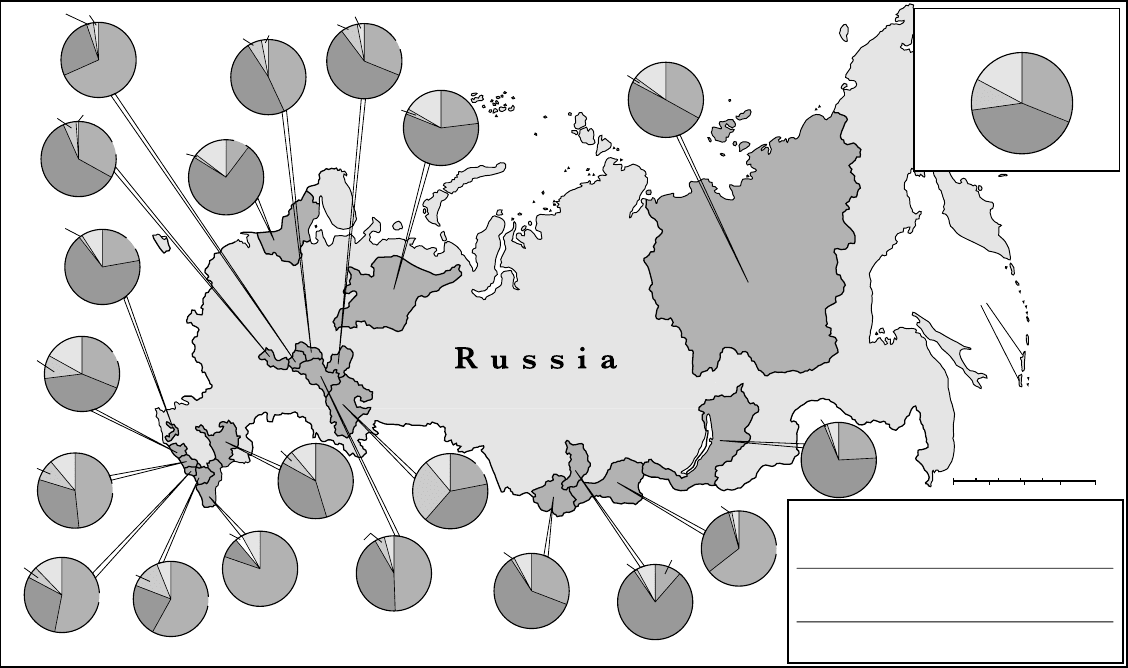

Map 13.1. Ethnic Republics in 1994

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

michael mcfaul

August 1991 may have punctuated the end of one regime, but did little to

define the contours of what was to follow. As in all revolutions, destruction of

the ancien r

´

egime came easier and more quickly than the construction of a new

order.

4

Throughout the autumn of 1991, it remained uncertain what kind of

political regime or economic system would fill the void left by the collapsing

Soviet state. Some within Russia were convinced that the command economy

had to be dismantled and replaced by a market system. Others had a different

view. Likewise, many within Russia spoke about the need to destroy the last

vestiges of autocracy and erect a democracy. But among these advocates of

regime change, there was little agreement about the ultimate endpoint. And

with hindsight, we now know that many powerful actors within the Soviet

Union had no intention of building democracy, as the majority of regimes in

place today in the states of the former Soviet Union are forms of dictatorship,

not liberal democracies.

5

Even the borders of the new political units were

unclear. And those who had a notion of what the endpoint should be regarding

political and economic change did not have a roadmap in hand for how to get

there.

Even if Yeltsin and his supporters had known precisely what they wanted

and had a blueprint for creating it, they still did not have the political power

to implement their agenda. In August 1991, Yeltsin of course was the most

popular figure in Russia. Yet, this popularity was ephemeral and perhaps not

as widespread as observers stationed in Moscow made it out to be. Yeltsin’s

authority was not institutionalised in either political organisations or state

offices. Even the powers of his presidential office – created just two months

earlier – were not clear. Equally ambiguous was the strength of those political

forces that favoured preservation of the Soviet political and economic order.

The coup had failed, but those sympathetic to the coup’s aims were still in

4 For elaboration of the frame of revolution as a method for understanding change in

post-Communist Russia, see Vladimir Mau and Irina Starodubrovskaya, The Challenge of

Revolution: Contemporary Russia in Historical Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press,

2001).

5 In his classifications of regimes in the former Soviet space at the end of 2001, Larry

Diamond ranks only three (Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania) as liberal democracies, one

(Moldova) as an electoral democracy, three (Armenia, Georgia, Ukraine) as ambiguous

regimes, two (Russia and Belarus) as competitive authoritarian regimes, five (Azerbaijan,

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan) as hegemonic electoral authoritar-

ian regimes, and one (Turkmenistan) as a politically closed authoritarian regime. See

Larry Diamond, ‘Thinking about Hybrid Regimes’, Journal of Democracy 13, 2 (Apr. 2002):

30. For arguments explaining this variation, see Steven M. Fish, ‘Democratization’s Req-

uisites’, Post-Soviet Affairs 14, 3 (1998): 212–47; Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way, ‘The Rise of

Competitive Authoritarianism, Journal of Democracy 13, 2 (Apr. 2002): 51–65; and Michael

McFaul, ‘The Fourth Wave of Democracy and Dictatorship: Noncooperative Transitions

in the Postcommunist World’, World Politics 54, 2 (Jan.2002): 212–44.

354

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

The Russian Federation

power in the government, the army, the KGB, in local governments and even

in the Russian Congress of People’s Deputies. Fearing a replay of 1917, Yeltsin

and his band of revolutionaries decided not to use force against their enemies.

In attempting to advance a peaceful revolution, however, the new leaders in

Moscow were constrained by lingering legacies of the Soviet era for the rest

of the decade.

Yeltsin and his allies, therefore, did not enjoy a tabula rasa in constructing a

new state, economy and political system after the 1991 coup. Although Russia’s

abrupt, revolutionary mode of transition removed guideposts for navigating

the transition, the non-violent nature of the transition also allowed many indi-

viduals, institutions and social forces endowed with certain rights and powers

in the Soviet system to continue to play important political and economic roles

in the post-Soviet era. The clash between fading old institutions and groups,

emerging new actors, forces and practices, and robust mutations between

the old and the new defined the drama in Russian history throughout the

1990s.

6

Dissolving the Soviet Union

In tackling the triple agenda of state formation, economic transformation and

regime change, Yeltsin made the creation of an independent Russian state his

first priority. He had no popular mandate for this momentous task. Only a few

months earlier, in March 1991, over 70 per cent of Russian citizens had voted

to preserve the Soviet Union. After the August coup attempt, however, Yeltsin

saw the dissolution of the Soviet Union as both inevitable and desirable. The

Baltic republics took immediate advantage of the power vacuum in Moscow

after the coup to push for complete independence from the Soviet Union.

Other republics followed the Baltic lead. The week after the coup attempt,

the Ukrainian Supreme Soviet voted overwhelmingly (321 in favour, 6 against)

to declare Ukraine an independent state, and set 1 December 1991 as the date

for a referendum to obtain a popular mandate for their decision. Georgia and

Armenia quickly followed by voting in September for full independence. At

the time, Gorbachev was still formally the president of the Soviet Union, but

in actuality he had little authority or power left to sanction these rebellious

6 At the beginning of the 1990s, the losers from change in the post-Communist order were

thought to be the greatest enemies of reform. See, most importantly, Adam Przeworski,

Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991). Later in the decade, those that benefited

from partial reform emerged as the real threat. See Joel Hellman, ‘Winners Take All: The

Politics of Partial Reform in Postcommunist Transitions’, World Politics 50 (1998): 203–34.

355