Strouthes D.P. Law and Politics: A Cross-Cultural Encyclopedia

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

JURISPRUDENCE

intention

not

coupled with

any

preparation

or

attempt

to

translate

the

intention into action

is

not

liable

for any

punishment—Even

after

having

an

intention

to

commit

a

crime

fol-

lowed

by

preparation

to

commit same,

if a

crime

is not

committed

for

some reason

the

mere

intention

or

preparation

is not

liable

to

punishment

specified

for the

crime

itself,

un-

less

the

preparation

by

itself

is

a

crime,

[p.

47]

B

(c)

Islamic

Jurisprudence—

—Crime

and

punishment—Intention—If

a

person

performs

a bad

deed with good inten-

tion,

the

badness

of

that action will remain

there,

[p.

47]C

(d)

Islamic

Jurisprudence—

—Crime

and

punishment—Qisas—If

a

group

of

persons kill

a

person, then

the

entire group

involved

in the

murder would

be put to

death

in

Qisas.

[p.

49]D

(e)

Islamic

Jurisprudence—

—Crime

and

punishment—Common

inten-

tion—If

several persons commit

an act of ag-

gression against

a

single person

in

furtherance

of

common intention,

all of

them would

be

liable

to

punishment,

[p.

50]

E

(f)

Penal

Code

(XLV

of

I860)—

—S.

34—Scope

and

implication

of

S.34,

P.P.C.

[pp.51,52]F8cG

Inam

Bux

v. The

State

(PLD 1983

SC

35); Sultan

v.

Emperor

(AIR 1931 Lah. 749)

and

Ibra

Akanda

v.

Emperor

(AIR 1944

Cal.

339(358):

45 Cr. LJ 771

ref.)

(g)

Penal

Code

(XLV

of

I860)—

—S.34—Constitution

of

Pakistan

(1973),

Art.

203-D—Repugnancy

to

Injunctions

of Is-

lam—Provision

of

S.34,

P.P.C. does

not of-

fend

any

Injunction

of

Islam.

An

individual involved

in a

criminal

act

may

not be

sufficiently

motivated

to

execute

his

criminal design

but

aided, abetted

and en-

couraged

by the

presence

and

participation

of

others

may

provide

him the

sufficient

tools

to

complete

the

offence.

The

culpability

of all the

accused

in

such

cases

is

co-extensive

and em-

braces

the

principal actor

and his

accessories

to the

act.

All the

participants with common

intention deserve like treatment

to be

meted

out to

them

in

law.

Section

34,

P.P.C. does

not

offend

any In-

junction

of

Islam, laid down

in the

Holy

Qur'an

and

Sunnah

of the

Holy

Prophet

(p.b.u.h.).

[p.53]H

Petitioner

in

person.

Iftikhar

Hussain

Ch.,

Standing Counsel

for

Respondent.

Date

of

hearing:

7th

October,

1992.

JUDGMENT

TANZIL-UR-RAHMAN,

C.

J.—1.

This

Sariat Petition challenges section

34 of

the

Pakistan Penal Code

on the

ground

of its

being repugnant

to the

Injunctions

of

Islam

as

laid down

in the

Holy

Qur'an

and

Sunnah

of

the

Holy

Prophet

(p.b.u.h.).

The

said

sec-

tion

is

reproduced

as

under:—

"S.34.

When

a

criminal

act is

done

by

several persons,

in

furtherance

of the

common intention

of

all,

each

of

such

persons

is

liable

for

that

act in the

same

manner

as if it

were done

by him

alone."

According

to

section

34,

when

a

criminal

act

is

done

by

several persons

in

furtherance

of

the

common intention

of

all, each

of

such

per-

sons

is

liable

for

that

act in the

same manner

as

if it

were done

by him

alone.

2. The

contention

of the

petitioner

is

that

in

Islam there

is no

punishment

for

intention.

Reliance

has

been placed

on the

following

verse:

"No

bearer

of the

burden

can

bear

the

burden

of

others."

(Al-Qur'an,

165:6).

It,

however, seems relevant

to

also quote

the

following verses

of the

Holy

Qur'an:—

120

JURISPRUDENCE

"Every soul will

be

held

in

pledge

for its

deeds." (Al-Qur'an, 79:38).

"In his

favor

shall

be

whatever good

he

does,

and

against

him

whatever evil

he

does." (Al-Qur'an, 2:286).

"If you

have

to

respond

to an

attack

(in

argument) respond only

to the

extent

of

the

attack leveled against you." (Al-

Qur'an,

16:126).

"And whatever (wrong)

any

human

be-

ing

commits rest upon himself alone."

(Al-Qur'an,

6:164).

3.

According

to the

above verses

of the

Holy

Qur'an

the

basic principle

of

Islamic

criminal justice seems

to be

that

the

person

who

commits

a

crime,

he

alone would

be li-

able

to

punishment

for the

commission

of the

crime

and no

other person would

be

liable

in

his

place.

4. As

regards

the

contention

of the

peti-

tioner

that

there

is no

punishment

for the

mere

intention,

the

following

Hadith

seems

to be

relevant

and are

thus quoted

below:—

(i)

"It is

reported

from

the

Holy

Prophet

(p.b.u.h.)

To

have said

that—

"Allah Almighty

has

exempted their fol-

lowers

from

any

penalty

for

what

is in

their hearts unless

it is

translated into

action."

(ii)

"It is

also reported

from

the

Holy

Prophet

(p.b.u.h.)

To

have said

that—

"The person

who

intends

to do any

vir-

tuous

act but

does

not

perform

it, a re-

ward shall

be

written

in his

account

and

the

person

who

intends

to

commit

a

crime

but for

some reason, does

not act

upon

it in

such circumstance, nothing

shall

be

recorded against him."

5.

Abu

Zahra,

a

renounced renowned

ju-

rist

of

Egypt

in his

Al-Jarima

wal

Uquba

fil

Shari'ah

Al-Islamia

page

350

writes

that—

"Mere intention

is not

subject

to

pun-

ishment unless

it is

done practically."

6.

On

account

of his

principle mere

in-

tention

not

coupled with

any

preparation

or

attempt

to

translate

the

intention into action

is

not

liable

for any

punishment.

Thus

even

after

having

an

intention

to

commit

a

crime

followed

by

preparation

to

commit

it, if a

crime

is

not

committed

for

some reason

the

mere

intention

or

preparation

is not

liable

to

pun-

ishment

specified

for the

crime itself, unless

the

preparation

by

itself

is a

crime.

7.

The

petitioner also submitted that

the

actions (liable

to

reward)

go

into intentions.

This

phrase

is, in

fact,

a

part

of a

long

Hadith

of

the

Holy

Prophet (p.b.u.h.) narrated

from

him

by

Hazrat

Umar.

This

Hadith

is

narrated

by

Imam

Bukhari

in his

Sahih

as

first

Hadith

under Kitab

al-Wahi

and is

also mentioned

in

Al-Mishkat

as the

first

Hadith

under Kitab

al-Imam.

After

the

above part

of the

Hadith

the

Holy

Prophet (p.b.u.h.) Said, i.e.,

a

human

being will

get (in

result) what

he

intends for.

It was

then stated

by the

Holy

Prophet

in

the

said

Hadith

that:

"i.e.,

who

migrates with

the

intention

to

seek pleasure

of

Allah

and His

Apostle,

his

migration

from

Makka

to

Madina

will

be for the

sake

of

Allah

and His

Apostle

and who

migrates

(from

Makka

to

Madina)

for

worldly gain

and

marry-

ing

with certain woman,

his

migration

will

be

relatable

to

that

intention

with

which

he

migrated."

Therefore,

it can be

inferred

that

if one

per-

forms

a bad

deed

with

good intention,

the

badness

of

that

action will remain there, e.g.,

if

a

person steals another's property

with

the

intention that

he

will help

the

poor with that

stolen property,

the

mere intention will

not

render

the

theft

as

lawful.

The

theft

will

re-

main

theft

and he

will

be

liable

to

punishment

in

accordance

with

law.

No

matter

the

inten-

tion

of

committing theft

may be

good.

121

JURISPRUDENCE

8. In so far as the

question

of

doing

an act

jointly

in

furtherance

of

common intention

and

its

liability

on

each

of

them

is

concerned,

it

seems pertinent

to

refer

to an

incident that

occurred

during

the

days

of

Umar,

the

second

Caliph.

It is

narrated

in

Al-Musannaf

Abi

Shaibah, Vol.

IX,

page

347

that—

"The husband

of a

woman

of the

city

San'a

disappeared

by

leaving

her

step-son

in

the

house.

In his

absence,

the

woman

had

illicit relations with

a

person

and

said

to her

friend

that this child will nickname

them

by

disclosing their relation

and

asked

him to

kill

the

child.

When

he re-

fused

to do so she

discontinued

her il-

licit relation with him. Ultimately,

the

woman,

her

friend,

her

servant

and an-

other person jointly agreed

to

kill

the

child. After killing, they

cut his

body into

pieces

and

then

threw

it

into

a

well.

When

the

incident came

to the

knowl-

edge

of the

people

the

Governor

of

Yemen

arrested

the

persons concerned.

He and

other culprits make confession

before

him.

The

Governor

of

Yemen

brought

the

matter into

the

notice

of

Hazrat

Umar.

In

reply,

Hazrat

Umar

or-

dered

him to

kill

all of

them

and

said

"By

God,

if all the

inhabitants

of

San'a par-

ticipated

in

committing

this

crime,

I

would have killed

all of

them."

9. The

same

incident

has

been stated

in

Al-Mufiqat

by

Imam Shatibi.

It

reads

as

under:—

"Hazrat Umar executed

five or

seven per-

sons

in

retaliation

of a

single person,

whom they

had

killed treacherously.

Be-

cause

Hazrat deemed

it

expedient

for the

protection

and

security

of

human lives.

If

several persons

are not

killed

in

retali-

ation

of a

single person, then

the

crime

of

human massacre will

not be

completely

eradicated

by the law

of

retribution.

Here

wisdom

may

hesitate, because

it

does

not

seem

to be a

protection

of

human lives

to

kill several persons

in

retaliation

of a

single person.

It was an

Ijtihad

of

Hazrat

Umar

to

have said,

'If

all

inhabitants

of

San'a

participated jointly

in

committing

this crime,

I

would have killed

all of

them/The

object

of his

declaration

was

the

protection

of

human lives

and to de-

ter

others

from

committing

the

crime.

However, Hazrat Umar

was not

sure

about

the

correctness

of his

decision

un-

til he

asked Hazrat

Ali

that

'if

you ap-

prehended

several

persons

in

committing

a

crime

of

theft,

would

you

order ampu-

tation

of

their

hands?'

Hazrat

Ali

said,

yes!

'The

same principle would

be ap-

plied

here.'Then,

Hazrat Umar ordered

to

kill

all of

them." (Al-Mufiqat

fi

Asul

al-Shari'ah,

Labi Ishaque

Al-Shatibi,

Vol.

Ill,

page

11

Dar

al-Ma'rafat,

Beirut,

Lebanon).

10.

There

is

another incident

that

Hazrat

Ali had

also ordered

the

execution

of

three per-

sons

in

retaliation

of

killing

a

single person.

It

is

thus

so

stated

in as

under:—

Likewise,

Hazrat

Ali

also executed, many

persons

in

retaliation

of

one

person

(This

precedent

is

followed

by the

majority

of

Jurists

and

Companions

of the

Holy

Prophet).

11.

Imam Malik,

in

Mu'atta

has

also been

quoted

as

saying that

if a

person catches hold

of

a

person

and

another kills

him and

then

it

is

found

that

he had

caught hold

of him for

being killed, then both would

be put to

death.

(Mu'atta: Imam Malik, Vol.

II, p. 873

Kitabl

Aqul-Babul-Qisas fil-Qatl).

12.

Maulana

Salmat

Ali in his

translation

of

Kitabul

Ikhtiyar

known

as

Islami Faujdari

Qanun

has

also stated

on the

authority

of

Al-

Kafi

that

if a

group

of

persons kills

a

person,

then

the

entire group involved

in the

murder

would

be put to

death

in

Qisas.

(Article 560,

p.

194).

122

JURISPRUDENCE

13. In

Fiqh

terminology,

two

words

Tawafuq

and

Tamalu'

are

very common

to

denote such

a

situation.

There

is,

however,

a

big

difference

between

the

Hanafis

and the

rest

of the

Jurists

in

determining

the

meaning

of

Tamalu'.

According

to

Jamhoor

Tamalu'

is

like Tawafuq

to

commit

a

crime jointly

with-

out

having prior agreement

or

conspiracy,

that

is

to say

they just agree

on the

spot

to

commit

a

crime jointly without prior planning

and

agreement.

While

according

to

Malikis

Jurists,

Tamalu'

meant

to

commit

a

crime jointly

by

several

persons

in

furtherance

of

common

in-

tention

and

prior agreement. According

to

them each member

of the

group shall

be li-

able

to

punishment

specified

for the

commis-

sion

of the

crime regardless

of

their direct

participation

in the

crime. Each

of

them would

be

considered

as it was

done individually.

14. In

other words, according

to

Malikis,

mere

presence

at the

spot

of

occurrence

of

crime

with

an

intention

of

such commission

is

sufficient

to

make

a

person liable

to

punish-

ment

for

such crime irrespective

of the

nature

of

his

participation

and

assistance. According

to

Hanafis, however,

all

participants shall

be

punished

with

a

punishment

of

Qisas

in the

case

of

murder

and the

person,

who

after

agreement,

merely

assists

at the

place

of oc-

currence

he

will, however,

be

awarded

Ta'zir

punishment

which

may go to the

extent

of

death punishment

but

only

as

Ta'zir,

not as

Qisas.

15.

According

to

Shafi'is

and

Hambalis,

all

will

be

liable

to the

same punishment pro-

vided they

all

intended

to

commit

the

said

crime

and

participate

in the

commission

of the

crime,

even

if

other person

or

persons engage

themselves

in

some minor

act

like beating with

a

stick, etc. However,

the

preferred opinion

of

the

Jumhoor

of the

Fuqaha (multitude major-

ity

overwhelming

of the

Jurists)

is

that

if

sev-

eral

persons participated

in

killing

a

single

person,

all of

them shall

be

liable

to

death

punishment.

Their

opinion

is, in

fact,

based

on

the

decision

of

Hazrat

Umar

who had ex-

ecuted seven persons,

in

retaliation

of

killing

a

single person

and is

reported

to

have said

that

if all

inhabitants

of

San'a

had

participated

in

committing

the

said crime,

I

would have

killed

all of

them,

as

referred

to

above.

16. It is

reported that there seems

to be

consensus

of

opinion among

the

Companions

of

the

Holy

Prophet (p.b.u.h.)

That

if

several

persons

commit

an act of

aggression against

a

single

person

in

furtherance

of

common

in-

tention,

all of

them would

be

liable

to

punish-

ment.

It is,

however, stated

in

Al-Muhalla

by

Imam

Ibn

Hazam Zahiri that

the

Compan-

ions

of the

Holy

Prophet (p.b.u.h.) Cannot

be

said

to be

unanimous

as

Ma'az

bib

Jabal,

a

prominent Companion

of the

Holy

Prophet

(p.b.u.h.)

Is

reported

to

have

not

agreed

on

the

issue

of

joint liability

with

Hazrat

Umar

and

Hazrat

Ali.

This

is so

stated

in Abu

Zahra's book, page

402

(ibid).

17.

However,

the

jurists

are of the

opin-

ion

that

if the

concept

of

joint liability

is ig-

nored,

then "Mischief

in the

land" will spread

on

earth.

The

criminals will conspire

to

com-

mit a

crime jointly

for the

purpose

of

availing

acquittal

of

some

of the

participants.

There-

fore,

it is

also

in the

interest

of

keeping peace

and

harmony

in the

society,

if the

acts com-

mitted with common intention

be

made pun-

ishable

for all and

each

of

them

for

committing

such crime.

18.

It

appears

that

this

Court

in

exercise

of

its suo

mo

tu

jurisdiction under

Article

203-

D(l)

of the

Constitution,

had

issued public

notice dated

30-8-1987

in

S.S.M.

No.

41-A

of

1987

to

examine some

of the

provisions

of

the

Pakistan Penal Code, 1860, including sec-

tion

34, and had

invited

the

opinions

of

law-

yers,

jurists

and

ulema

etc.

A

public notice

appeared

in the

National Dailies

of

Pakistan,

both Urdu

and

English

and the

Court started

examination

of the

said section

34

along with

certain

other provisions

of the

Pakistan Penal

123

JURISPRUDENCE

Code

from

17th

to

21st January, 1988

at

Islamabad

and the

matter

was

heard

on

dif-

ferent

dates

at

Karachi, Lahore

and

Quetta

during 1989

and

1990,

but

there appears

to

be

no

judgment written

or

pronounced

in the

said

S.S.M.

No.

41-A

of

1987, with

the

result

that section

34,

P.P.C.,

now

under consider-

ation also remained undecided.

19. It

may, however,

be

mentioned

that

in

response

to the

earlier publication

of the

public notice

in the

Dailies

of

Pakistan,

a

num-

ber

of

Scholars submitted their comments

on

the

different

provisions

of law in a

general

form.

However, Professor

Fazle

Hadi

Qasmi

of

Peshawar, made

his

comments

on

certain

sections

of the

Pakistan Penal Code

as

asked

for.

About section

34 his

comments

are re-

produced

as

below:

20.

Section

34, as

reproduced (supra), only

enacts

a

rule

of

co-extensive culpability when

offence

is

committed with common intention

by

more than

one

accused. Meeting

of

more

than

one

mind

in

doing

an act

(intended

as

agreed)

to an

offence

can be

said

to

result

in

having common intention

in

doing

it.

That

creates

co-extensive criminal liability under

this section.

The

principle which

is

embodied

in

section

34, is

participation

in

some

act

with

the

common intention

of

committing

a

crime.

If one

such participation among more than

one

person

is

established section

34 is

attracted.

The

Hon'ble

Supreme

Court

of

Pakistan

in

Inam

Bux

v. The

State (PLD 1983

SC 35)

has

thus held that:

"Section

34 of the

Penal

Code,

1860

is

intended

to

meet

a

case

in

which

it may

be

difficult

to

distinguish between

the

acts

of

individual members

of a

party

who

act

in

furtherance

of the

common

inten-

tion

of

all.

It

does

not

create

a

distinct

offence

but

merely enunciates

a

principle

of

joint

liability

for

acts done

in

further-

ance

of

common intention animating

the

accused

leading

to the

doing

of a

crimi-

nal

act in

furtherance

of

such intention.

Common intention usually consists

of

some

or all of the

following acts; com-

mon

motive, pre-planned preparation

and

concert pursuant

of

such plan, com-

mon

intention, however

may

develop

even

at the

spur

of the

moment

or

dur-

ing the

commission

of the

offence.

The

principle enunciated

is

that

if two

or

more persons intentionally

do a

thing

jointly

the

position

is

just

the

same

as if

each

of

them

had

done

it

individually

by

himself."

21. To

understand

and

appreciate

the im-

plications

of

section

34 it

seems necessary

to

also

refer

to

sections

35, 37 and

38,

P.PC.

Section

34

deals with

the

doing

of

separate

acts, similar

or

diverse,

by

several persons;

if

all are

done

in

furtherance

of a

common

in-

tention, each person

is

liable

for the

result

of

them

all as if he had

done them himself. Sec-

tion

35 in

effect

provides

for a

case where sev-

eral

persons join

in an act

which

is not per se

criminal,

but is

criminal only

if it is

done with

a

criminal knowledge

or

intention;

in

such

a

case

each

of

those persons

who

joins

in the act

with that particular knowledge

or

intention

will

be

liable

for the

whole

act as if it

were

done

by him

alone with

that

knowledge

or

intention,

and

those

who

join

in the act but

have

no

such knowledge

or

intention will

not

be

liable

at

all. Section

37, in

effect,

provides

for

a

case where several persons cooperate

in

the

commission

of an

offence

by

doing sepa-

rate acts

in

different

times

or

places, which

acts,

by

reason

of

intervening intervals

of

time,

may

not be

regarded

as one act or

which

may

not be

necessarily committed with

a

common

intention. Section

38

provides that

if

several

persons

are

engaged

or

concerned

in the

com-

mission

of a

criminal act, having been

set in

motion

by

different

intentions, they

may be

guilty

of

different

offences

by

means

of

that

act.

This

section, which

is the

converse

of

sec-

tion

34,

provides

for

different

punishments

for

different

offences

where

several

persons

are co-

accused

in the

commission

of a

criminal act,

whether such persons

are

actuated

by the one

124

JUSTICE

intention

or the

other.

The

basic principle

which runs through

all

these sections

is

that

an

entire

act is to be

attributed

to a

person

who may

have

performed

only

a

fractional

part

of

it.

Sections

35, 37 and 38

begin

by

accept-

ing

this proposition

as

axiomatic,

and

each

of

them then goes

on to lay

down

a

rule

by

which

the

criminal liability

of the

doer

of a

fractional

part (who

is to be

taken

as the

doer

of the en-

tire act),

is to be

adjudged

in

different

situa-

tions

of

mens

rea.The

axiom itself

is

laid down

in

section

34 is

which emphasis

is on the

act.

What

has to be

carefully

noted

is

that

in

sec-

tion

35

and in

section

37 and in

section

38

this axiom that

the

doer

of the

factional

act is

the

doer

of the

entire

act is

taken

up as the

basis

of a

further

rule.

Without

the

axiom these

sections

would

not

work,

for it is the

founda-

tion

on

which they

all

stand. Reference

may

be

made

to

Sultan

v.

Emperor (AIR 1931 Lah.

749

(750)

and

Ibra

Akanda

v.

Emperor (AIR

1944

Cal.

339

(358):

45 Cr. LJ

771).

22. Mr.

Iftikhar Hussain Chaudhary,

learned

counsel

for the

Federal Government,

submitted that

the

principle

of

collective

re-

sponsibility

is

well-established

in

history.

The

Holy

Qur'an mentions extinction

of the

tribes

of

Ad

andThamud.

These

people

had

aban-

doned

the

worship

of

true

god and

lapsed into

incorrigible idolatry.

To Ad,

Hazrat

Hud was

sent

but

they

did not

believe

him and the

tribe

was

obliterated

from

the

face

of the

earth

by a

hot and

suffocating

wind that blew

for

seven

nights

and

eight

days

without intermission

and

was

accompanied

by a

terrible earthquake.

The

idolatrous tribe

of

Thamud

was

bestowed with

the

presence

of

Hazrat

Salih

but the

unbe-

lievers

persisted

in the

incorrigible impiety

and

a

violent storm overtook them

and

they were

found

prostrate

on

their breasts

in

their abodes.

Thus,

groups, tribes, people

or

nations were

given

punishment

for

their collective wrong-

doings

and

males,

females

and

children were

treated alike.

23. The

above instances,

as

quoted

by the

learned Standing Counsel

for the

Federation,

seem

to be out of

context

as

they relate

to the

law

of

creation/extinction

whereas

we are at

the

moment concerned

with

the

legislation

as

to the law of

crime

and

punishment.

24. It may

thus

be

stated that

an

indi-

vidual

involved

in a

criminal

act may be

suffi-

ciently motivated

to

execute

his

criminal

design

but

aided, abetted

and

encouraged

by

the

presence

and

participation

of

others

may

provide

him the

sufficient

tools

to

complete

the

offence.

The

culpability

of all the

accused

in

such

cases

is

co-extensive

and

embraces

the

principal actor

and his

accessories

to the

act.

All the

participants with common intention

deserve

like treatment

to be

meted

out to

them

in

law.

25. We

are, therefore,

of the

considered

view

that

the

above section

34,

RRC. does

not

offend

any

Injunction

of

Islam, laid down

in

the

Holy

Qur'an

and

Sunnah

of the

Holy

Prophet (p.b.u.h.).

26. The

petition

is,

therefore,

dismissed

as

being without merit.

Petition

dismissed.

The

All

Pakistan

Legal

Decisions.

(1993) Vol.

45.

Edited

by

Malik

Muhammad Saeed.

Austin, John.

(1954)

The

Province

of

Jurispru-

dence

Determined

and the

Uses

of

the

Study

of

Jurisprudence.

Pospisil, Leopold. (1974

[1971])

Anthropology

of

Law:

A

Comparative

Theory.

The

subject

of

justice

is

a

very complex one. Jus-

tice

may

play

a

role

in

virtually

all

aspects

of the

law.

In

many societies,

125

Jusna;

JUSTICE

Justice,

represented

as a

blindfolded

'woman

holding

a

sword

and

scales

on

which

to

weigh

truth,

rests

on a

throne

in an

eighteenth-century

engraving.

the

concepts

of law and

justice

are

virtually

in-

distinguishable

from

one

another,

and it is be-

lieved

in

those societies

that

the

purpose

of the

law

is to

provide justice.

However,

it is not

true

that

the law is al-

ways

just,

or

even

that

law

always provides jus-

tice.

In

Nazi Germany,

for

example, Adolf

Hitler

committed many injustices

in

killing people

in

his

concentration camps,

but

these injustices

were

strictly legal

at the

time

in

Germany.

While

it is

probably true that

all

societies

have

concepts

of

justice, ideas about what spe-

cifically

constitutes justice vary

from

society

to

society.

Among

the

Koreans,

justice

is

often

con-

ceived

of as

being synonymous with virtue.

In

Western legal traditions, equality,

or

equity

(in

France,

egalite),

is

often

thought

to be the

goal

of

justice.

Among

the

Kapauku Papuans

of New

Guinea, justice

is

known

as

uta-uta,

or

"half-

half,"

showing that they conceive

of

justice

as a

balance between

the

parties.

Most

questions

of

justice

focus

on the

jus-

tice

of the

law. However, there

is

another cat-

egory

of

justice known

as

justice

of the

facts.

In

order

for a

legal authority

to

render

a

decision,

he or she

must discover

and

investigate

the

facts

of

the

dispute. Justice

of the

facts

concerns

the

quality

of the

information

that

the

legal author-

ity

uses

to

decide

a

case.

What

is

important

in a

legal action

is

what

the

legal authority assumes

happened,

and not

what actually happened.

It is

usually

the job of the

legal authority

to

objec-

tively seek

the

truth with regard

to the

facts

of

the

case,

and so the

authority must consider

the

possibility

that

witnesses

lie and

that

both par-

ties

to a

case have committed

offenses.

The le-

gal

authority must determine credibility,

and

will

sometimes

use the

standard

of the

reasonable

man

in

determining this.

Among

the

Kapauku

of

Papua,

New

Guinea

(Pospisil, 1971: 237),

the

legal authority

has an

advantage

over legal authorities

in

Western

courts

in

that

he has the

opportunity

to

hear

the

parties

to a

case

argue violently over

it, and in so

doing

may

hear more

of the

truth than

he

would

hear in a

calm courtroom

in the

West.

The

legal authorities

of the

Micmac

Indi-

ans

of

eastern Canada

are

lucky

in

that they usu-

ally

never have

to

worry about justice

of the

facts.

All of the

true

facts

of the

case

are

presented

to

them

in

short order

by the

parties

to the

case.

The

plaintiff

will

tell

the

headman

or

Indian

act

chief (legal authority)

truthfully

what

the

alleged

wrongdoer

has

done,

but

will omit whatever

of-

fensive

acts

he or she has

himself

or

herself com-

mitted.

Then

the

headman

or

chief will

go to

the

alleged wrongdoer.

The

alleged wrongdoer

will admit

the

truthful allegations made

by the

plaintiff,

and

will then accuse

the

plaintiff

of the

commission

of

offensive

acts, which

the

plain-

tiff

had

neglected

to

mention.

In

short,

the

usual

legal strategy

of the

alleged wrongdoer

is to

claim

that

the

plaintiff

is

without "clean

hands"

(has

126

JUSTICE

himself

or

herself done wrong things

in

relation

to the

case,

and

should

not

therefore have just

cause

to

complain).

The

alleged wrongdoer

will

also

argue

the

interpretation

of the

facts,

and

the

application

of the

appropriate

law or

rule

to

the

facts,

but

will rarely deny true facts.

The

second branch

of

justice

is the

justice

of

law.

This

may be

further

broken down into

justice

of

adjudication

and

justice

in

principles

of

the

law. Justice

in

adjudication

may

either

be

formal,

involving uniformity

in

application

of

legal principle

and

equal sanction

for

equal

crimes,

or it may be on a

case basis,

with

the

merits

and

demerits

of

each case weighed sepa-

rately.

For

example,

the

Micmac Indians

are firm

believers

in

formal

justice

in

adjudication.

They

believe

that

all

similar

offenses

should

be

treated

in

exactly

the

same way.

Their

insistence

on

uni-

formity

is

largely

a

result

of the not

uncommon

practice

of

legal authorities making decisions

on

the

basis

of

political

self-interest

and in the in-

terest

of

benefitting

kin and

friends

with

light

sanctions;

corruption

of the

legal system

is all

too

common

in a

community

in

which

all

people

know each other

and/or

are

related through kin-

ship

to

each other.

When

deciding principles

of

law,

it is im-

portant

to

treat crimes

of

relative equality

in

much

the

same manner,

to

decide which crimes

are

more reprehensible than others, and,

in

democratic

systems,

to

ensure

that

certain classes

of

people

do not

receive preferential treatment.

Accordingly, among

the

Ifugao

people

of the

Philippines,

fines are

adjusted

on the

basis

of

wealth.

The

poor

pay one

amount

for a

particu-

lar

offense,

those

of the

middle class

pay a

higher

amount,

and the

wealthy

pay the

greatest

fine.

Natural Law, equity,

and the

standards

of

the

reasonable man, discussed

in

their

own en-

tries,

are all

doctrines applied

to the

question

of

justice

in

adjudication.

Many legal scholars,

on the

other hand, have

been

interested

injustice

in

principles

of the

law.

That

is,

they want

to

know whether

the

prin-

ciples behind

the

legal decisions themselves

are

just.

How is it

that

one

assesses

the

justice

of le-

gal

principles?

One has to

look

at

questions

of

substantive

justice,

the

goal

of

which

is to

pro-

vide

a

scale

of

values

in

order

to

make such

as-

sessments.

One

such scale

of

values

was

provided

by

the

doctrine

of

Natural Law.

The

other

part

of

substantive justice

is

pro-

cedural justice.

This

involves

the way in

which

large philosophical doctrines, such

as

Natural

Law,

are

converted into actual laws

to be

used

in

the

regulation

of

human society. Ideas

on

this

subject

are, like those pertaining

to

substantive

justice, largely philosophical,

and are

treated

in

the

entry

on

Legal Anthropology.

See

also

EQUITY;

LEGAL ANTHROPOLOGY; NATU-

RAL

LAW;

REASONABLE

MAN.

Barton,

Roy F.

(1969

[1919])

Ifugao

Law.

Bohannan, Paul

J.

(1957a)

Justice

and

Judgement

among

the

Tiv.

Gluckman,Max.

(1967

[1955])

The

Judicial

Pro-

cess

among

the

Barotse

of

Northern

Rhodesia.

Pospisil, Leopold. (1974

[1971])

Anthropology

of

Law:

A

Comparative

Theory.

Strouthes, Daniel

P.

(1994)

Change

in the

Real

Property

Law

of

a

Cape

Breton

Island

Micmac

Band.

127

KINGSHIP

Kingship

maybe

defined

as

a

type

of

political

leadership

in

which

the

leader

of a

society rules

with

divine right

or di-

vine

power.

In

many kingdoms,

the

king

or

queen

is

believed

to

have descended

from

a

god,

or

to

himself

or

herself actually

be a

god. King-

doms

differ

from

theocracies

in

that

the

latter

are

governed

by

religious practitioners, such

as

priests, rather than

by the

objects

of

veneration

themselves.

Kingship

was

found

in

many places

through-

out the

world

in

traditional times, including

Europe, India, Polynesia

and

other parts

of

Oceania, China, Cambodia, Japan, West

and

East

Africa,

Mexico (the Aztec),

and

Peru (the

Inca).

Where

monarchies remain

in the

mod-

ern

world, they have lost most

of

their power.

Yoruba

kings,

for

example,

are

under

the

power

of

the

Nigerian government,

and the

monarchs

of

Great Britain, Japan,

and the

Netherlands

are

subordinate

to

national parliaments.

Kingdoms

are

generally regarded

as

state

societies. Furthermore,

in

most

if not all

cases,

the

monarch

is

regarded

as the

personification

of

the

society's

people

and its

lands.

These

char-

acteristics,

along with

the

characteristic

of di-

vine

rule,

are all

that kingdoms around

the

world

seem

to

have

in

common.

Differences

in

suc-

cession,

power, duties, responsibilities,

and a

host

of

other

factors distinguish

one

society's

royalty

from

that

of

another.

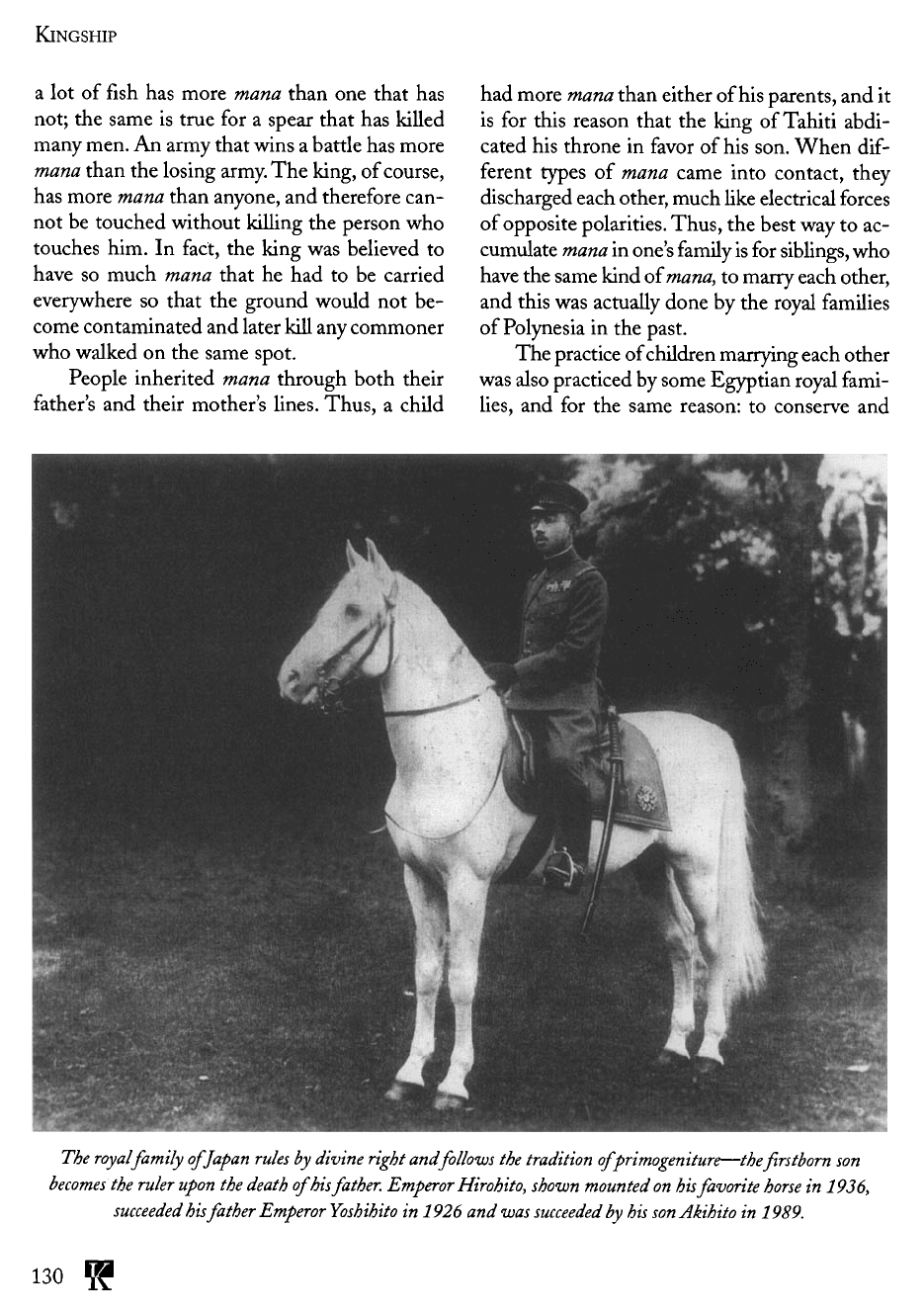

For

instance, Yoruba kings (only males

can

be

monarchs)

are in an

alternating fashion

elected

from

one of two

segments

of the

royal

lineage.

In

comparison,

the

British

and

Japanese

monarchs

descend according

to

primogeniture,

while

the

Tibetan

monarch,

the

Dalai Lama,

is

by

ordinary kinship reckoning unrelated

to his

predecessor.

Some monarchs

can

abdicate

the

throne, such

as

those

in

Great Britain,

but

Yoruba

kings

can

only leave

office

in

death

(on

the

other hand, those

who

elected

the

Yoruba

king could require

him to

commit suicide

by

drinking poison).

The

supernatural qualities ascribed

to

mon-

archs

vary along

with

differences

in the

official

religions

to

which

the

monarchs belong.

The

British monarch

is the

head

of the

Church

of

England,

but not a

god, whereas

the

Japanese

emperor

and

Polynesian kings

and

queens

are

themselves

deities. Neither

the

Japanese emperor

nor the

Polynesian monarch

may be

touched

by

a

commoner.

The

reason

that

the

Polynesian monarch

may

not be

touched

by a

commoner illustrates

the

differences

and

similarities

in the

divine

power held

by

monarchs.

The

Polynesian mon-

arch

was

believed

to

possess more

of a

super-

natural power called

mana

than anyone else.

Mana

is a

formless

supernatural power that

may

be

likened

to an

electrical charge,

in

that

it can

be

transferred

by

contact.

A

person with very

little

mana

can be

killed

by

touching someone

with

a

great deal

of

mana,

and

someone

with

a

great deal

of

mana could lose

it by

touching

su-

pernaturally

polluted objects. Mana

is

univer-

sal,

the

Polynesians believe,

and

present

to

some

degree

in all

objects.

A fish

hook that

has

caught

129

k

KINGSHIP

a

lot of fish has

more mana than

one

that

has

not;

the

same

is

true

for a

spear that

has

killed

many

men.

An

army that wins

a

battle

has

more

mana

than

the

losing army.

The

king,

of

course,

has

more mana than anyone,

and

therefore can-

not be

touched without killing

the

person

who

touches him.

In

fact,

the

king

was

believed

to

have

so

much mana

that

he had to be

carried

everywhere

so

that

the

ground would

not be-

come

contaminated

and

later kill

any

commoner

who

walked

on the

same spot.

People inherited mana through both their

fathers

and

their

mothers

lines.

Thus,

a

child

had

more mana than either

of his

parents,

and it

is

for

this reason that

the

king

of

Tahiti

abdi-

cated

his

throne

in

favor

of his

son.

When

dif-

ferent

types

of

mana came

into

contact, they

discharged each other, much like electrical

forces

of

opposite polarities.

Thus,

the

best

way to ac-

cumulate

mana

in one

s

family

is for

siblings,

who

have

the

same kind

of

mana,

to

marry each other,

and

this

was

actually done

by the

royal families

of

Polynesia

in the

past.

The

practice

of

children marrying each other

was

also practiced

by

some Egyptian royal fami-

lies,

and for the

same reason:

to

conserve

and

The

royal

family

of

Japan

rules

by

divine right

and

follows

the

tradition

of

primogeniture—the

firstborn

son

becomes

the

ruler

upon

the

death

of

his

father. Emperor

Hirohito,

shown

mounted

on

his

favorite

horse

in

1936,

succeeded

his

father Emperor

Yoshihito

in

1926

and

was

succeeded

by his

sonAkihito

in

1989.

130