Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Fortune (1999), Louis Malle in Vanya on 42nd Street (1994),

James Ivory in Surviving Picasso (1996), Joel Coen in The Big

Lebowski (1997), and

STEVEN SPIELBERG

in The Lost World:

Jurassic Park 2 (1997). Her work in Boogie Nights (1997)

earned her a Best Supporting Actress Oscar nomination. In

1999 her performance in The End of the Affair garnered a Best

Actress Oscar nomination. The same year, she appeared in

Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia. In 2001 she was selected

to play Clarice in Hannibal, the Silence of the Lambs sequel. By

2002, Moore was riding high, starring with Dennis Quaid in

the faux 1950s melodrama Far from Heaven and with

MERYL

STREEP

and

NICOLE KIDMAN

in The Hours. Both pictures

earned Academy Award nominations for Moore.

M.O.S. An abbreviation of the words “mit out sound,”

this is a German/English expression meaning “without

sound.” A scene shot without dialogue or sound effects is said

to be M.O.S. and is also known as a wild picture. Conversely,

sound recorded without a picture is known as wild sound.

The expression mit out sound and its subsequent abbre-

viation came into common Hollywood usage in the early

sound era. Lothar Mendes, a Hungarian director who

worked in Austria and Germany before coming to the United

States, is commonly credited with introducing the quaint

expression into the Hollywood vocabulary when, working on

a picture, he asked for a scene “mit out sound.” The Ameri-

can crew was amused and the expression caught on.

Today, whenever a wild picture is being shot, the letters

M.O.S. are written on the clapper board to indicate to the

editor that the scene to follow is intended as silent.

Motion Picture Patent Company See

EDISON

,

THOMAS A

.

MPAA Acronym signifying the Motion Picture Associa-

tion of America, an organization of major film distribution

companies, headed by

JACK VALENTI

and headquartered in

Washington, D.C.

Muni, Paul (1896–1967) He was Warner Bros.’s class

act during the 1930s, a star with the stature to pick his own

roles at a studio that was notorious for shoving its actors into

any available project. Though he certainly was a star, Muni

was a powerful character actor who immersed himself in his

roles to such an extent that he was sometimes unrecognizable

from one movie to the next, but his undeniable talent was

always apparent.

Born Muni Weisenfreund in Austria, he came to America

with his family when he was still quite young. His parents had

a theatrical background, so it wasn’t very strange for Muni to

become active in the New York Yiddish theater. He made the

leap to Broadway in 1926 when he replaced

EDWARD G

.

ROBINSON

in We Americans. His next Broadway play, Four

Walls, made him a genuine stage star.

Muni was not ignored in Hollywood’s rush for Broadway

actors during the talkie revolution of the late 1920s. He

starred in the Fox film The Valiant (1929), which did poorly

at the box office but showcased Muni’s talent, garnering him

an Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. He made

another film that same year for Fox, Seven Faces, in which he

played seven different characters. That, too, failed to find an

audience, and Muni seemed to lack the broad appeal needed

to sustain a Hollywood career.

He returned to Broadway in 1931, scoring a major suc-

cess in Elmer Rice’s play about a Jewish lawyer, Counsellor-at-

Law. The play was later made into a movie starring John

Barrymore.

When producer

HOWARD HUGHES

decided to make a

gangster picture, he was looking for a fresh face to play the

vicious Al Capone-like protagonist. He and director

HOWARD HAWKS

settled on Muni, bringing him back to Hol-

lywood for Scarface (1932). The movie was a gigantic hit, and

the actor’s film career was firmly established.

Soon thereafter,

WARNER BROS

. gambled on Muni to star

in their controversial exposé of the Southern penal system, I

Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1933). It was a gamble that

paid off at the box office and in prestige both for the studio

and the actor.

M.O.S.

288

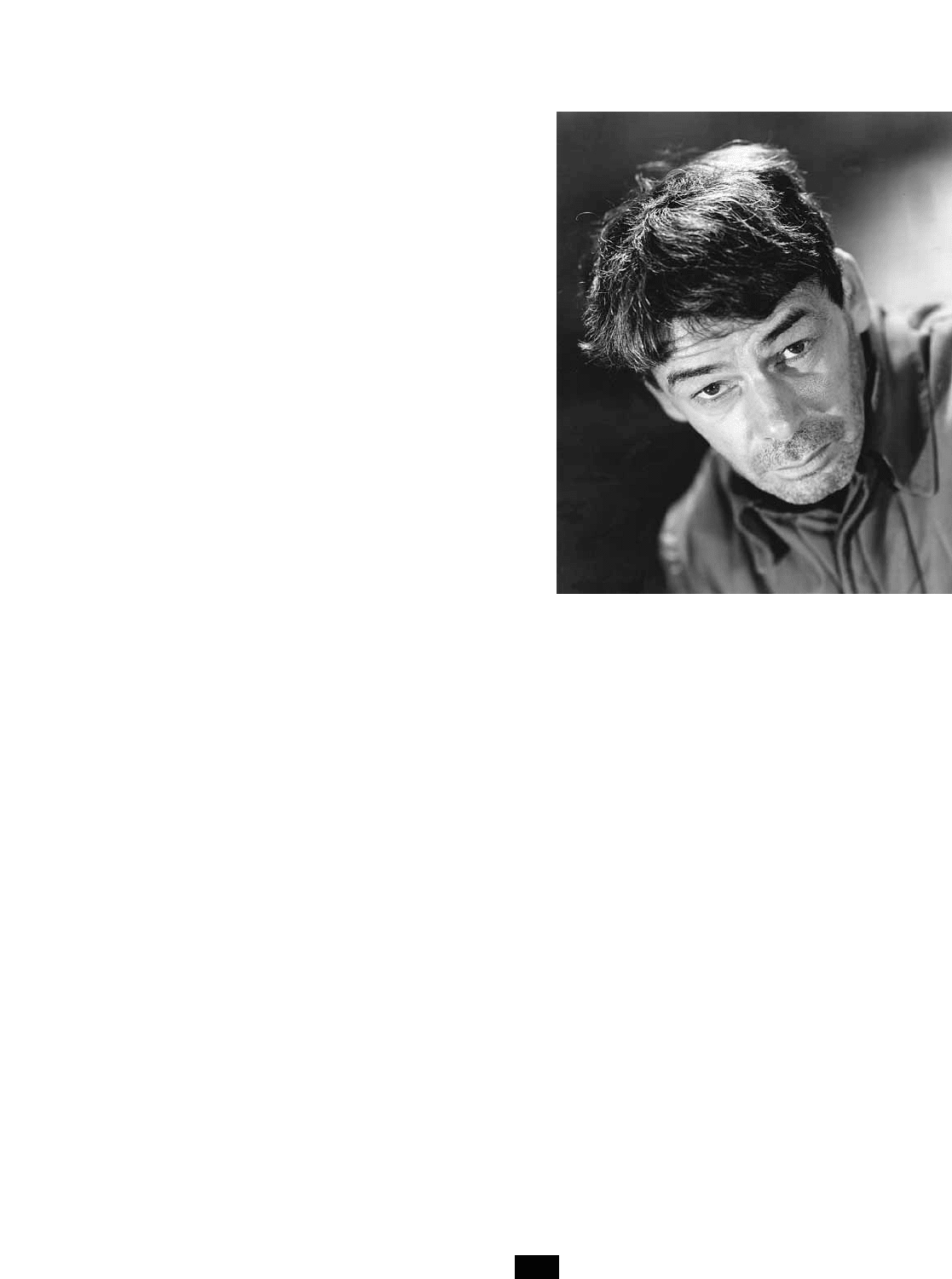

Paul Muni was a powerhouse actor who liked to change both

his appearance and his voice from film to film. He was the

leading dramatic actor at Warner Bros. during the 1930s,

particularly in that studio’s successful cycle of biopics.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

Muni was given a long-term contract at Warner Bros.

that lasted until the end of the 1930s, during which time he

starred in (among other projects) a famous series of biogra-

phical films. He was Pasteur in The Story of Louis Pasteur

(1936), a movie Warners was hesitant to make but that

earned a fortune and won Muni a Best Actor Oscar. Muni was

Zola in The Life of Emile Zola (1937), a film that won Best Pic-

ture honors, and Benito Juárez in Juarez (1939), perhaps his

most impressive performance.

In addition to the various nationalities he assumed in

BIOPICS

, Muni played a Chinese in his starring role in The Good

Earth (1937). But Muni never played in comedies or farces; he

was far too strong a force for such films and instead played

characters such as the angry striking miner in Black Fury (1935).

Although Muni was the most prestigious actor on the

Warners lot, he wasn’t always the most successful at the box

office. By the late 1930s, his films were losing money. The

studio wanted Muni to play a gangster again, harking back to

his original success in Scarface, but Muni refused. He turned

down the tough-guy role in High Sierra (1941); the part even-

tually went to

HUMPHREY BOGART

and turned him into a star.

Muni and Warner Bros. parted company at the end of the

1930s, and the actor went back to Broadway. He starred in

any number of plays, including Key Largo, which eventually

became another Bogart starring vehicle in 1948.

He starred in a handful of other films during the 1940s

and early 1950s but nothing of the caliber of his 1930s

movies. Muni did, however, make one final triumphant

return to the big screen in The Last Angry Man (1959) as an

aging doctor fighting disease and despair in the slums.

Though it didn’t make waves at the box office, both he and

the movie were well received by the critics. It was an effective

and memorable swan song.

Murphy, Audie (1924–1971) His fame as the most

decorated soldier of World War II brought the boyish-look-

ing G.I. a Hollywood career that lasted more than 20 years.

Murphy, who gave a sense of realism to his action roles, had

a surprisingly long career, especially in “B” movie westerns.

Born the son of a poor Texas sharecropper, Murphy’s fame

as a war hero brought him to the attention of

JAMES CAGNEY

,

who suggested that he consider making a living as an actor.

Murphy took Cagney’s advice. The slightly built veteran

appeared in a small role in Beyond Glory (1948). His first star-

ring role came shortly thereafter in Bad Boy (1949), a movie

about juvenile delinquents. In fact, throughout much of his

acting career, Murphy played teenaged characters because of

his baby face.

Out of his 44 films, Murphy appeared in 33 westerns. But

two of his nonwesterns are worth special mention. He starred

in the

JOHN HUSTON

production of The Red Badge of Courage

(1951), a cult favorite that Murphy considered his best movie.

He also starred in a film version of his autobiography, To Hell

and Back (1955), a smash box-office hit and the biggest

money-maker in Universal-International’s history.

During the course of his career, Murphy almost single-

handedly kept the “B” western alive, making them long after

ALAN LADD

,

RANDOLPH SCOTT

, and

JOEL MCCREA

either

died or retired. Despite a general impression that he was only

a mildly popular actor, Murphy was voted the top western

box-office draw by theater owners in 1955, and that was dur-

ing the heyday of

JOHN WAYNE

.

Although most of his films received little recognition,

there were some gems among them, such as No Name on the

Bullet (1959) and Arizona Raiders (1965). Because of his box-

office appeal, he occasionally appeared in “A” westerns,

such as The Unforgiven (1960) with

BURT LANCASTER

and

AUDREY HEPBURN

.

Murphy also produced two westerns, in both of which he

appeared, The Guns of Fort Petticoat (1957) and his last movie

A Time for Dying (1971). The latter film, directed by

BUDD

BOETTICHER

, was released after Murphy’s sudden and tragic

death in a plane crash in North Carolina.

Murphy made it a point never to trade directly on his war

record—he wouldn’t allow mention of it in the publicity for

any of his films—but the audience knew who he was and what

he stood for. Despite his cherubic face, there was a hint of

menace about him. John Huston referred to Murphy during

the making of The Red Badge of Courage as “my gentle little

killer.” That combination of innocence and danger was a

large part of his appeal.

See also

WESTERNS

.

Murphy, Eddie (1961– ) An actor-comedian who

zoomed to Hollywood superstardom in the early 1980s on

the basis of just three films. Clearly, Murphy has become one

of the very few talents whose name on a marquee ensures a

box-office hit (as of this writing he has not had a single flop).

His brash, cocky humor, coupled with a disarming personal

charm, has brought him a legion of fans. Although Murphy’s

comedy is often harsh and jarring, it has much of the crude

honesty of the early

RICHARD PRYOR

, whom he has over-

taken as Hollywood’s leading black comedy star.

Murphy was born in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn,

New York. His father was a New York City cop and amateur

comedian who died when the future star was eight years old.

Raised by his mother and his stepfather, Murphy soon

showed a flair for comedy. He began to write and perform his

own routines at youth centers and local bars when he was 15.

When Murphy performed at the Comic Strip, a showcase

that has launched many a comedian’s career, owners Robert

Wachs and Richard Tienken were so impressed that they

agreed to manage him. Events moved swiftly after that.

At the age of 19, Murphy landed an audition for the new

cast of TV’s Saturday Night Live and was signed as a featured

player for the 1980–81 season. He was an instant hit on the

show, staying with the program for four years and creating

such memorable characters as the prison poet Tyrone Green,

the grownup Buckwheat, the grumpy Gumby, and the TV

huckster/pimp Velvet Jones.

Saturday Night Live had already served as a springboard

for movie comedy stars

CHEVY CHASE

,

DAN AYKROYD

, John

Belushi, Bill Murray, and Gilda Radner; it seemed logical for

Murphy to try his luck in the movies, as well. His first film

MURPHY, EDDIE

289

was 48 Hours (1982), in which he costarred with

NICK

NOLTE

; it was a smash hit and Murphy was highly praised as

a natural actor. For his second film, he teamed with Dan

Aykroyd in Trading Places (1983), which was another winner.

Though Murphy shared top billing and did not carry

either of his first two films, that changed with his third film,

Beverly Hills Cop (1984). The movie established him as one of

Hollywood’s biggest box-office draws.

Murphy had generally received good reviews from the

critics for his first three films. That changed with The

Golden Child (1986) and Beverly Hills Cop II (1987), but it

didn’t keep his fans away. Both films made a bundle at the

box office.

Meanwhile, Murphy continued to appear on TV, make

records, and tour. Two of his comedy concerts were recorded

on film and edited into a motion picture that was released to

theaters as Raw (1988), the biggest money-maker in concert-

film history. He followed that success with his most ambi-

tious project to date, Coming to America (1988), a major hit

and a highly regarded movie by critics who were impressed

with Murphy’s growth as an actor and his willingness to play

a character rather than simply play himself as he had done in

most of his previous work.

Buoyed by his success, Murphy next made Harlem Nights

(1989), which he also wrote, directed, and produced. In the

film, he and Richard Pryor play nightclub owners who are

determined to keep their club, despite the efforts of the mob

and corrupt cops. Like most of his films, the movie was a

financial success. He played a congressman in The Distin-

guished Gentleman (1992), and in Boomerang (1992) he played

an executive harassed and exploited by Robin Givens before

finding happiness with

HALLE BERRY

. His role as a vampire

searching for lost love Angela Bassett in Vampire in Brooklyn

(1995) was not a hit with the critics, but Murphy fans still

turned out in droves. In 1998 he was G, a spiritual salesman

for a home shopping network in Holy Man, a satire on mate-

rialistic Americans.

Although he has taken on roles that are not entirely sim-

ilar to his established persona, Murphy has more often

appeared in films in which he reprises earlier roles, and

sequels are a large part of his stock in trade. Although the

content was repetitive and the plots stale, the films did well

financially. He reappeared as Nick Nolte’s sidekick in Another

48 Hrs. (1990), reprised his Axel Foley role in Beverly Hills

Cop 3 (1994), and played a Foley-type role in Metro Man

(1996). In Life (1999), he teamed with Martin Lawrence in a

story about two men who are framed for a crime and then are

jailed. Murphy seems at his best when he can play off another

actor, often a white one.

Murphy was also into remakes in the 1990s, starting with

The Nutty Professor (1996), an outlandish updating of the

JERRY LEWIS

film (1963). Murphy played eight different

roles. (In the sequel, Nutty Professor 2: The Klumps (2000), he

repeated his feat.) In Bowfinger (1999), he again played a dou-

ble role, this time as Kit Ramsay, a film star with a nerdy twin

brother who does Kit’s stunts. In the film, wannabe film-

maker

STEVE MARTIN

attempts to get Kit to appear in his

film. In a role that would seem quite a stretch even for him,

Murphy played the title role in Dr. Doolittle (1998), a remake

of the 1967 original starring Rex Harrison, and then repeated

his role in Dr. Doolittle 2 (1999). In the sequel, Murphy

played a Bill Cosby–like dad, quite a departure from his ear-

lier “raw” roles.

Two of Murphy’s best roles were in animated films. In

Disney’s Mulan (1998), he played Mushu, a puny dragon who

attempts to help the feminist Chinese warrior Mulan. In fact,

the film uses Mushu as a parallel to Mulan: Both Mulan and

Mushu don different disguises, have quests, and try to prove

themselves worthy. Murphy voiced Donkey in Shrek (1999),

a vengeful satire aimed at the Disney studio. Murphy’s role—

he stole the film—won him a British Academy nomination as

Best Supporting Actor.

The actor-comedian has not been content merely to per-

form. He has become a one-man conglomerate, establishing

Eddie Murphy Productions (for film projects), Eddie Mur-

phy Television Productions, and Eddie Murphy Tours (a con-

cert producing company).

musicals The first talkie,

THE JAZZ SINGER

(1927), was also

Hollywood’s first musical. It’s well known that the

AL JOLSON

MUSICALS

290

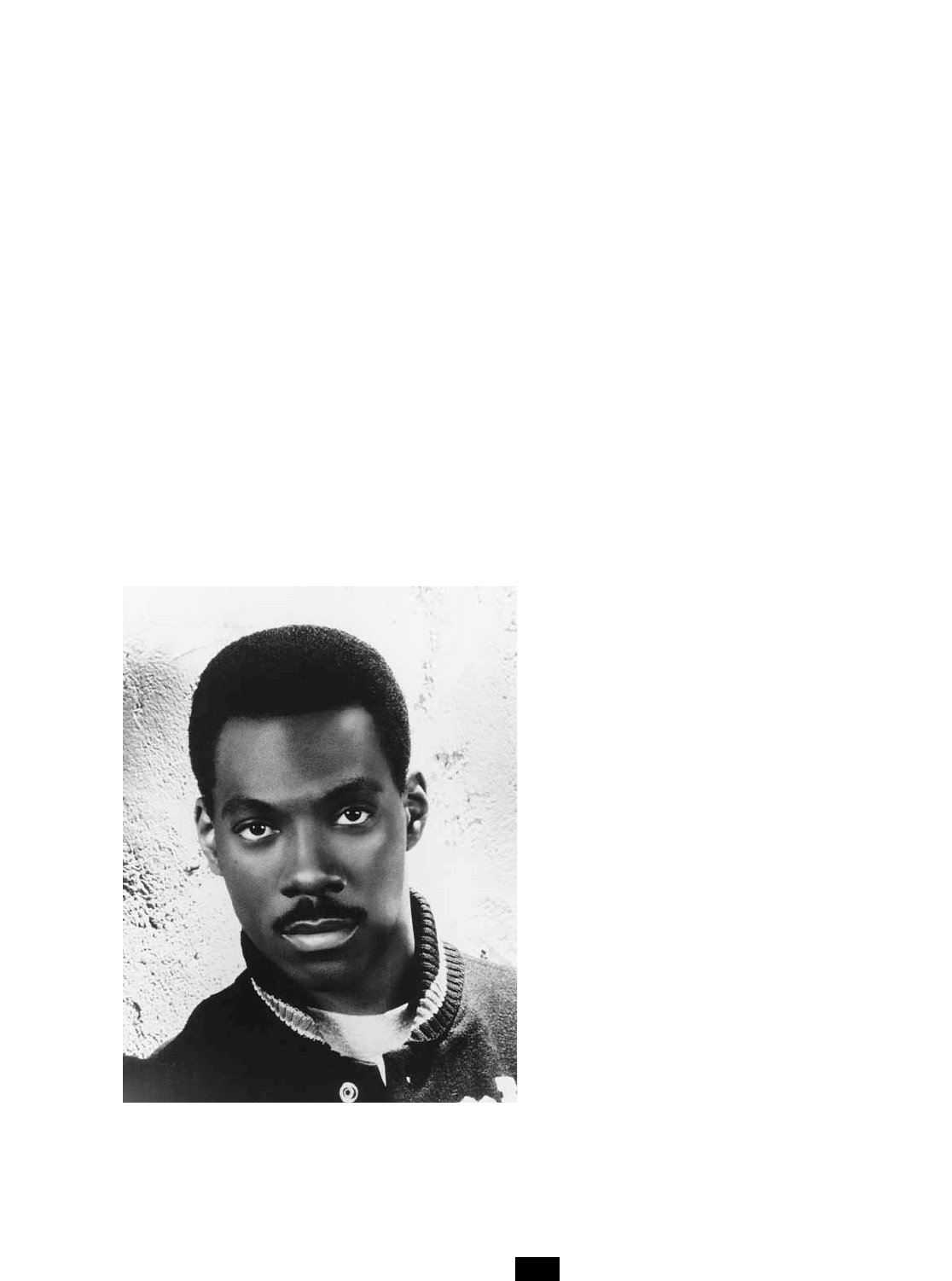

Eddie Murphy has become the most commercially success-

ful comedian in Hollywood history, with several of his most

recent films taking in well more than $100 million at the

box office.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF EDDIE MURPHY)

vehicle ignited the sound revolution, but it is less well known

that its success also led to a deluge of musicals during the next

several years that nearly killed the genre in its infancy. Every

studio advertised their “all talking, all singing, all dancing”

films as they desperately tried to take full commercial advan-

tage of the new sound technology. As a result, so many

mediocre musicals were made in such a relatively short period

of time that box-office returns soon began to fall precipi-

tously. It was the flowering of the classic movie musicals in the

early 1930s that resurrected the genre, but even before that

happy event, two basic kinds of musicals had already emerged,

the singing musical and the dancing musical. All other sub-

categories fall within these two major groups.

The singing musical is the broader of the two groups

because there have been very few dancers with large enough

popular appeal around whom films could be built. Though

often containing at least some dancing, the singing musical

primarily focuses on musical numbers, comedy, and, on occa-

sion, drama, but almost always it hinges on romance. Among

early singing musicals, one finds the charming and risqué

ERNST LUBITSCH

operettas The Love Parade (1929), Monte

Carlo (1930), and The Merry Widow (1934),

ROUBEN

MAMOULIAN

’s brilliant Love Me Tonight (1932), as well as the

more dramatic operettas of Nelson Eddy and

JEANETTE

MACDONALD

, such as Naughty Marietta (1935) and Rose

Marie (1936).

Many out-and-out comedies were also leavened with

songs and can also be considered singing musicals, among

them the films of

EDDIE CANTOR

and many

MARX BROTH

-

ERS

,

ABBOTT AND COSTELLO

,

MARTIN AND LEWIS

, and

DANNY KAYE

movies.

A lesser form of the singing musical could be found in the

westerns of

GENE AUTRY

and

ROY ROGERS

. The popularity

of these singing cowboys during the 1930s and 1940s was

quite substantial. The country-western and hillbilly music of

the singing cowboy merged in the 1950s with the rockabilly

sound of

ELVIS PRESLEY

and a subsequent boom in rock ’n’

roll musicals. Presley, alone, made 33 movies, the vast major-

ity of them formula musicals that earned in excess of $150

million at the box office.

With rare exceptions, such as Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942)

and The Story of Vernon and Irene Castle (1939)—films about

dancers—most musical biopics were essentially singing musi-

cals, such as Night and Day (1945), The Jolson Story (1946),

Words and Music (1948), The Great Caruso (1951), The Helen

Morgan Story (1957), The Buddy Holly Story (1978), and La

Bamba (1987).

Great though many of the singing musicals are, the glory

of the genre ultimately belongs to the dance musicals. When

one thinks of the movie musical, images of

FRED ASTAIRE

and

GENE KELLY

come immediately to mind, or perhaps one

thinks of the

BUSBY BERKELEY

spectaculars of the 1930s or

the Broadway musical extravaganzas of the 1950s and early

1960s. For most people, these films are the pinnacle of movie

musical art.

The dance musical had its start in the musical review

films of the late 1920s and early 1930s, including movies such

as The Hollywood Revue of 1929 (1929) and Paramount on

Parade (1930). Though dance numbers did not dominate

these movies, audiences responded with great enthusiasm to

the sights and sounds of dancing feet.

By the early 1930s, the time was ripe for full-scale danc-

ing movies. Busby Berkeley breathed new life into the musi-

cal and created a dynamic visual style when he choreographed

and directed the musical numbers in Footlight Parade (1933),

Gold Diggers of 1933 (1933), and 42nd Street (1933). These lav-

ish, audacious works have never been duplicated. For

instance, the very idea of putting 100 dancing pianos on

screen (which Berkeley presented in Gold Diggers of 1935) was

both wonderfully silly and thoroughly awe-inspiring. His

work at

WARNER BROS

. reaffirmed that studio’s leadership in

the musical genre after its initial success with Al Jolson.

Berkeley’s “mass” extravaganzas, with scores of scantily

clad women creating kaleidoscopic effects (e.g., forming

images of violins, flowers, etc.), were in contrast to the “inti-

mate” musicals that were characterized by the subtle, grace-

ful, and elegant dance numbers of Fred Astaire and

GINGER

ROGERS

, whose musicals were equally popular during the

1930s. Astaire and Rogers, in films such as The Gay Divorcée

(1934), Top Hat (1935), and Swing Time (1936), created the

yardstick by which intimate dance films would be measured

forevermore. Astaire, in particular, whose dancing career on

film spanned four decades, was Hollywood’s preeminent

dance musical star; he was the only musical performer who

had a major impact during the flowering of the musical in

the 1930s and also its golden era during the late 1940s and

early 1950s.

With varying degrees of success, each studio pursued its

own course in the profitable musical genre, and more often

than not, a musical performer helped save several studios

from bankruptcy. For instance, RKO avoided Chapter 11

thanks to the enormous success of Fred Astaire and Ginger

Rogers in the 1930s, helped greatly by the unheralded but

extremely bright producer

PANDRO S

.

BERMAN

. Also in the

1930s,

DEANNA DURBIN

sang Universal out of near-insol-

vency, just as

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

kept the wolf from the door

at Twentieth Century–Fox until they developed such other

popular musical stars as

ALICE FAYE

and

BETTY GRABLE

.Of

course, not every leading musical performer was a savior, but

many were immeasurably important to their studio’s bottom

line. For example,

DICK POWELL

warbled very profitably for

Warner Bros. in innumerable musicals during the bulk of the

1930s.

BING CROSBY

was a major asset at Paramount, just as

RITA HAYWORTH

was worth millions to Columbia. Even the

independent

SAMUEL GOLDWYN

had his musical stars: Eddie

Cantor in the 1930s and Danny Kaye in the 1940s and 1950s.

Then there was MGM, which boasted “more stars than there

are in the heavens”; by the late 1930s, a good many of them

were musical stars. The studio produced few musicals during

most of the 1930s but finally began to emerge as a power-

house in the genre with such films as The Wizard of Oz (1939)

and Babes in Arms (1939), eventually becoming the predomi-

nant creator of musicals in the 1940s and 1950s.

One of MGM’s performers was Gene Kelly, whose exu-

berant and acrobatic dance style, especially in films such as

The Pirate (1948), On the Town (1949), and Singin’ in the Rain

MUSICALS

291

(1952), gave the musical a shot in the arm. After Fred Astaire,

Kelly has been the most influential of movie musical per-

formers, often cochoreographing and codirecting many of

his greatest triumphs.

Astaire and Kelly, as well as such talents as

JUDY GAR

-

LAND

,

MICKEY ROONEY

, Mario Lanza, and

CYD CHARISSE

were all all part of MGM’s famous “Freed Unit.”

ARTHUR

FREED

, a noted songwriter and producer, put together an

awesome assemblage of musical talent, presiding over the

creation of many of the film industry’s most illustrious musi-

cals. With the assistance of such innovative directors as

VIN

-

CENTE MINNELLI

and

STANLEY DONEN

, the Freed Unit

produced such memorable hits as Meet Me in St. Louis (1944),

Ziegfeld Follies (1946), Till the Clouds Roll By (1946), Easter

Parade (1948), Summer Stock (1950), An American in Paris

(1951), and Show Boat (1951). It was also during this time that

MGM pioneered the so-called wet musical featuring

ESTHER

WILLIAMS

in elaborate aquatic production numbers.

The musical was ever changing. The movie industry was

under siege during the 1950s, losing patrons and revenue to

television. Jut as Hollywood turned to epics and spectaculars

to compete with the little box, so did the movie musical

become more epic in its scope, adapting big Broadway musi-

cals to the screen such as Oklahoma! (1955), The King and I

(1956), and West Side Story (1961).

The movie musicals—both the singing and dancing vari-

eties—finally collapsed under their own budgetary weight.

After a spate of hugely successful singing Broadway-musical

adaptations, including My Fair Lady (1964), The Sound of

Music (1965), and Funny Girl (1968), film companies poured

massive amounts of money into a series of very poor musi-

cals, such as Doctor Dolittle (1967), Star! (1968), and Hello,

Dolly! (1969), which were staggering box-office failures, sour-

ing the movie industry on the genre.

The musical, however, is resilient, and Bob Fosse fought

the tide with three innovative dance musicals that had force

and subtlety: Sweet Charity (1968), Cabaret (1972), and All

That Jazz (1979). But Fosse’s films were too idiosyncratic to

reestablish the genre to its former popularity. This was

accomplished, however, by the success of the “disco” musical

Saturday Night Fever (1977), which proved there was a strong

and vibrant youth market for dance musicals. Since then,

teen dance musicals have been extremely popular, as evi-

denced by such hits as Flashdance (1983), Footloose (1984), and

Dirty Dancing (1987).

Outside of the youth market, there has been little in the

way of big movie musicals. Small-scale musicals such as Ta p

(1989) kept the musical tradition alive, while leading movie

musical stars tend to ignore the genre.

BARBRA STREISAND

and

LIZA MINNELLI

, for instance, prefer to make nonmusi-

cals (when they make films at all) because of the enormous

time and effort required to make elaborate musicals such as

Streisand’s Yentl (1983).

In recent years, the one Hollywood personality who has

worked most consistently in musicals has not been a star but

a director,

HERBERT ROSS

, who has made such musicals as

Funny Lady (1975), The Turning Point (1977), Nijinsky (1980),

Pennies from Heaven (1981), and Dancers (1987). Throughout

most of the 1990s, musicals remained the territory of ani-

mated movies. Disney produced several hit features, includ-

ing The Little Mermaid (1999), Beauty and the Beast (1999),

Aladdin (1999), and The Lion King (1999), all of which fea-

tured numerous memorable musical numbers. Some of these

movies proved so popular that they later became Broadway

stage productions. All that changed with Moulin Rouge

(2001), Baz Luhrmann’s stylish musical feature, which mixed

popular songs with new material and starred

NICOLE KID

-

MAN

and Ewan MacGregor in a tongue-in-cheek melo-

drama. The film was a hit. Chicago (2002) followed, bringing

the long-running Broadway smash to the big screen and fea-

turing

RICHARD GERE

, Catherine Zeta-Jones (an

ACADEMY

AWARD

winner), and Renee Zellweger.

MUSICALS

292

Negri, Pola (1894–1987) Before Garbo and Dietrich,

there was Pola Negri—the original femme fatale from the

Continent. The green-eyed, raven-haired beauty brought a

sensual and exotic presence to Hollywood. Unfortunately,

her American films tended to use her as a conventional lead-

ing lady, smothering the spark that had ignited audience

interest in her in the first place.

Born Barbara Apollonia Chalupiec, Negri entered the

theater world in Russia as a dancer. After some considerable

success in cabaret, she returned to Poland, where she wrote

and produced her first film, whose English title is Love and

Passion (1914). Quickly becoming Poland’s most successful

film star, she was convinced by producer Max Reinhardt to

travel to Germany, where she conquered yet another audi-

ence. More significantly, she demanded and received directo-

rial guidance from a relative unknown,

ERNST LUBITSCH

.

The two teamed to make a remarkable series of hit movies,

many of which were well received in America.

Negri was deluged with offers from Hollywood studios.

She finally accepted an $8,000-per-week contract from Para-

mount and made her first film in the United States in 1923

(Bella Donna). Neither her first nor many of her subsequent

films were successful. Rather surprisingly, critics liked her

but audiences did not. Happily,

ERNST LUBITSCH

was also

brought to America, and he directed her in Forbidden Paradise

(1924), a movie that was highly regarded by both critics and

the public.

Though she continued making movies, her hits became

fewer. Even Negri’s personal life took a beating with the sud-

den death of

RUDOLPH VALENTINO

, with whom she was

engaged in a romantic affair.

Sound dealt the final blow. Negri made a few talkies (she

even sang in two of them), but her accent was considered too

heavy by Paramount executives. When her contract ran out

in 1928, so did she—back to Europe.

The singing success of

MARLENE DIETRICH

, however,

offered Negri new encouragement. She returned to America

in 1932 and made A Woman Commands at RKO. She sang

again—and rather well—but the movie was an especially bad

vehicle and Negri left Hollywood.

She returned to Germany, reestablished her film career

there, and (rumor had it) became romantically involved with

Adolf Hitler. Nevertheless, Negri fled Germany during

World War II and returned to America. She made just two

more films, Hi Diddle Diddle (1943) and Disney’s The Moon-

spinners (1964).

Newman, Paul (1925– ) An actor-director-producer

who has been a movie mainstay for more than 40 years.

Blessed with strikingly handsome features, talent, and the

bluest eyes in Hollywood, Newman has generally opted for

challenging roles rather than typical matinee-idol parts. His

popularity as an actor has been matched by the appreciation of

his peers, who have nominated him a total of seven times for

the Best Actor Academy Award; he has won the statuette once.

Born to a well-to-do Cleveland family, Newman served in

the navy during World War II before attending Kenyon Col-

lege as an economics major. While in school, he developed an

affinity for acting, and he eventually continued his education

at the Yale School of Drama. His most important training,

however, took place at the Actors Studio, where he became

one of a number of influential performers to emerge as devo-

tees of the Method approach to acting.

Newman’s rise to fame was meteoric. Not long after his

stint at the Actors Studio, he landed a leading role in the 1953

production of the hit play Picnic. He was immediately tapped

for the movies. Because of his looks and his Actors Studio

training, Newman found himself in constant competition

with

JAMES DEAN

, another actor who seemed cut from the

293

N

same cloth. Hoping to make his film debut as the misunder-

stood son yearning for love in Elia Kazan’s East of Eden (1955),

Newman saw the role given to Dean. In fact, Newman was

able to make his movie debut in The Silver Chalice (1955) only

when Dean declined the offer. (Dean, it should be said, made

the wiser choice—the biblical epic was panned by the critics.)

The two actors’ careers continued to be linked; the role of

Rocky Graziano in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956) had

been slated for Dean until he died in a car accident. Newman

took over the part, and it became his first hit film.

It was the first of many. During the next 15 years New-

man was the hottest actor in Hollywood. He peaked at the

end of the 1960s, had a rather poor decade in the 1970s, but

reemerged in the 1980s with some of the best performances

of his career. In fact, his Oscar nominations tend to uphold

that assessment. He was nominated for Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

(1958), The Hustler (1961), Hud (1963), Cool Hand Luke

(1967), Absence of Malice (1981), The Verdict (1982), and finally

took home the honor for a reprise of his Fast Eddie role from

The Hustler in The Color of Money (1986).

Newman’s hits defined the emerging Hollywood of the

late 1950s and 1960s. In an effort to outshine television, Hol-

lywood turned to adult dramas, and Newman could be seen

in The Long Hot Summer (1958), The Left-Handed Gun (1958),

and Sweet Bird of Youth (1962). The 1960s were a time of

growing alienation, and Newman reflected the zeitgeist with

such films as The Outrage (1964), Harper (1966), Hombre

(1967), and Cool Hand Luke (1967). Yet, Newman could also

be the typical Hollywood leading man, as evidenced by his

starring roles in A New Kind of Love (1963), The Prize (1963),

Torn Curtain (1966), and the ultimate crowd pleaser, Butch

Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), which marked his popu-

lar highpoint. The film also made a megastar out of his

costar,

ROBERT REDFORD

, the man who supplanted Newman

as Hollywood’s romantic ideal.

As one of the original cofounders of First Artists, along

with

BARBRA STREISAND

,

SIDNEY POITIER

, and

STEVE

MCQUEEN

, Newman was in a position to control more of his

work, and he did so during the 1970s, producing and direct-

ing a number of films. He began to direct in the late 1960s,

making Rachel, Rachel (1968), a film starring his wife,

JOANNE

WOODWARD

, that was well received, if not a major box-office

success. He went on to produce and direct several other

films, including the highly underrated Sometimes a Great

Notion (1971), in which he also starred, and three other vehi-

cles for his wife, The Effect of Gamma Rays on Man-in-the-

Moon Marigolds (1972), The Shadow Box (1980), and The Glass

Menagerie (1988).

Newman also produced, but did not direct, many of his

own films during the early 1970s, among them, WUSA

(1970), Pocket Money (1972), The Life and Times of Judge Roy

Bean (1972), and The Drowning Pool (1975). None of them

were big hits. He had a string of real duds at the end of the

decade and the very beginning of the 1980s, including Buffalo

Bill and the Indians . . . or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976),

Quintet (1979), and When Time Ran Out (1980). His only big

winners as an actor during the 1970s were The Sting (1973),

in which he reteamed with Robert Redford, the all-star The

Towering Inferno (1974), and Slap Shot (1977).

He recouped smartly in the 1980s, becoming once again

the powerful box-office force that he had been in his early

years, and making much better movies in the bargain. Fort

Apache, The Bronx (1981) was a controversial hit that put

Newman back in the spotlight. His troubles with the media

during that film led him to make the intelligent and thought-

provoking Absence of Malice (1981), a film that dealt with the

power of the press to destroy innocent people. He continued

making quality films throughout the 1980s, including his

semiautobiographical Harry and Son (1984), which he wrote,

produced, and directed. It was a film that touched on the dif-

ficult relationship between a man and his son, and it owed

much to Newman’s experience with the death of his son by

drug overdose in 1978.

Outside of the film industry, Newman has been politically

active in liberal causes and has become well-known for his

various food products, the profits of which he donates to

charity. He is also a highly visible racecar driver who became

especially interested in the sport during the making of Win-

ning (1969).

In 1985, Paul Newman was given a special Oscar in honor

of his fine work. In his acceptance speech, he told the academy

NEWMAN, PAUL

294

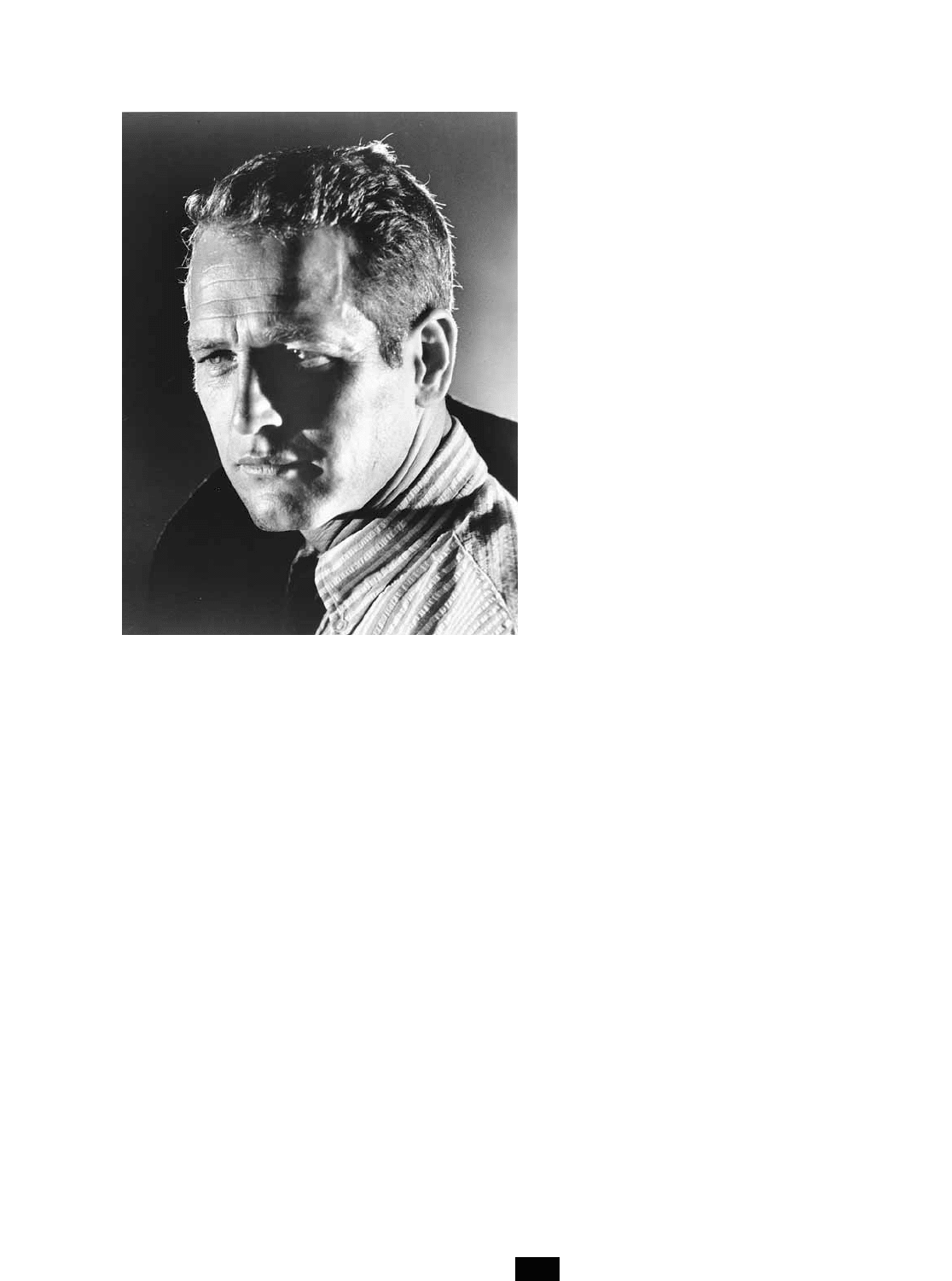

Paul Newman has been both a sex symbol and one of the

film industry’s most accomplished leading men since the

mid-1950s.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

not to write him off, that he wasn’t through yet. The follow-

ing year he won the Best Actor Award for The Color of Money.

Newman and Woodward appeared together in Mr. and

Mrs. Bridge (1990), a critically acclaimed film in which he

perhaps had his best performance, but the Oscar nomination

went to his wife. After appearing in the Coen brothers’ The

Hudsucker Proxy (1993), his acting talent was recognized for

his role as Donald “Sully” Sullivan, a 60ish guy attempting to

mend relationships in Nobody’s Fool; he received Best Actor

awards from the Berlin Film Festival, the New York Film

Critics, and the National Board of Review, and also received

Best Actor nominations for a Golden Globe and an Oscar. In

1998 he played an ex-cop, ex-private detective in Twilight and

Kevin Costner’s father in Message in a Bottle, a film in which

he overshadowed Costner. Newman also starred as an aging

mob boss in Road to Perdition (2002), again being nominated

for an Oscar.

newsreels Nonfiction film footage once shown in movie

theaters on a regular basis, newsreels became a form of movie

journalism that lasted for more than 60 years. Although never

as timely or as comprehensive as the news one might find in

daily newspapers, America’s newsreels supplied not only facts

but also unforgettable images. The newsreel was a standard

part of movie fare, presented to audiences along with a car-

toon or short subject, as well as coming attractions and at

least one (if not two) feature films.

A few current-events films were made before the advent

of newsreels, such as the Bob Fitzsimmons and Jim Corbett

heavyweight bout in 1897, Queen Victoria’s funeral in 1901,

and the San Francisco earthquake of 1906 (some of which

was faked through the use of miniatures). As Raymond Field-

ing reports in his excellent book, The American Newsreel, the

first ongoing series of news shorts produced in America was

begun in 1911 by the French-owned Pathé’s Weekly. The

success of Pathé’s Weekly was such that competition blos-

somed in the form of companies such as Fox News, which

went into business in 1919.

The talkie revolution slowed the newsreel business down

for a short while because of the difficulty of recording sound

on film in sometimes treacherous situations that were hardly

suited for moviemaking. Nonetheless, sound newsreels soon

flourished, the most powerful and far-reaching of them being

Fox Movietone News. Lowell Thomas later become the

voice of Fox Movietone News and his name, face, and voice

became famous worldwide. Other newsreel companies

included Hearst Metrotone, Universal Newsreel, Paramount

News, and in 1935, the famous March of Time newsreel

begun by Time, Inc.

The March of Time was the forerunner of the TV news-

magazine and therefore the predecessor of such shows as

Sixty Minutes and 20/20. It differed from its newsreel compe-

tition in focusing its full 20 minutes on only one subject,

examining it in considerable depth. Though the newsreel did

not pretend to be neutral in its point of view, its passion made

it rich and fascinating. The March of Time won a special

Oscar in 1937 for “having revolutionized one of the most

important branches in the industry—the newsreel.” The

March of Time remains one of the best remembered of all

the newsreels because Orson Welles mimicked it so well in

his masterpiece, Citizen Kane (1941).

Newsreels captured some of the best-remembered events

of the century, such as the Lindbergh flight, the startling

assassination of King Alexander of Yugoslavia in 1934, and

the famous Hindenburg catastrophe in Lakehurst, New Jersey,

in 1937, but newsreels also covered such areas of interest as

fashion, sports events, celebrities, political campaigns, and

natural disasters.

The stories of daredevil camera operators who often

risked their lives to shoot dangerous footage became the stuff

of legend. They worked their way into Hollywood features

when

CLARK GABLE

and

MYRNA LOY

starred in Too Hot to

Handle (1938), a movie using the world of newsreels as its

backdrop. Yet the most dangerous news footage, shot during

war, was usually handled by army camera operators. During

both World War I and World War II, civilians were rarely

permitted to film at the front, but no matter who was filming,

relatively little of what was shot was ever seen by audiences

on the home front—most of the images were too terrifying

for civilians to witness and the military banned their showing.

The newsreel began to fade in importance during the

1950s because it couldn’t compete with television’s ability to

report the news almost instantly. But contrary to popular

belief, the newsreel did not die an early death due to TV and

continued on well into the 1960s. The fact is that many of the

newsreel companies began to shoot their footage for TV

news rather than for theater distribution. With video replac-

ing film, even that source of revenue began to dry up. The

king of the newsreels, Fox Movietone News, stopped pro-

ducing in 1963. Hearst Metrotone lasted until November 30,

1967, and the last holdout, Universal Newsreel closed their

doors on December 26, 1967.

Nichols, Dudley (1895–1960) An Oscar-winning

screenwriter who wrote literate, intelligent movies for a vari-

ety of wildly diverse first-class directors. Though he wrote,

directed, and produced three movies himself, Nichols is

remembered as one of Hollywood’s most influential and suc-

cessful screenwriters.

A former reporter for the New York World, he arrived in

Hollywood in 1929 when studios were in dire need of writers

to script the new talking pictures. He wrote his first screenplay

for Men Without Women (1930), directed by

JOHN FORD

, with

whom Nichols would collaborate in the course of nearly two

decades. All told, Nichols scripted 15 Ford films, including The

Lost Patrol (1934), Judge Priest (1934), Stagecoach (1939), and

The Long Voyage Home (1940). He also wrote the screenplay for

Ford’s The Informer (1935), a film that won Oscars for both

Ford (Best Director) and Nichols (Best Screenplay). His last

screenplay for Ford was The Fugitive (1947).

Nichols had no trouble finding work when he wasn’t writ-

ing for Ford. He scripted

HOWARD HAWKS

’s wonderful

screwball comedy Bringing Up Baby (1938), along with two

other Hawks classics, Air Force (1943) and The Big Sky (1952).

NICHOLS, DUDLEY

295

He wrote the screenplays for Jean Renoir’s best American

films, Swamp Water (1941) and This Land Is Mine (1943). The

clever and disturbing thriller Man Hunt (1941) and the film

noir Scarlet Street (1945) were projects that he scripted for

FRITZ LANG

, and The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945) is a fondly

remembered film that he penned for

LEO MCCAREY

. For

ELIA

KAZAN

, he wrote the antiracist Pinky (1949), and for

ANTHONY MANN

, he scripted the fine western, The Tin Star

(1957). Nichols wrote his last film (not counting the 1966

remake of Stagecoach, which used his original script), the off-

beat western Heller in Pink Tights (1960), for

GEORGE CUKOR

.

Nichols wrote, produced, and directed three films: Gov-

ernment Girl (1943), Sister Kenny (1946), and Mourning

Becomes Electra (1947). All were well received by the critics,

even if they weren’t particularly successful at the box office.

Nichols, Mike (1931– ) A director who has made a

number of intelligent, entertaining, and often hard-hitting

movies since beginning his film career in 1966. Nichols is also

a very successful stage director who has not deserted Broad-

way for Hollywood: He has continued to move back and forth

between film and stage with gratifying results in both. A for-

mer cabaret performer, Nichols is known for working very

well with actors. He is also a good judge of talent, having dis-

covered

DUSTIN HOFFMAN

and Whoopi Goldberg.

Born Michael Igor Peschkowsky in Berlin, Germany, he

was seven years old when he emigrated with his Jewish family

to the United States to avoid persecution at the hands of the

Nazis. Nichols was 12 years old when his father died, but he

managed to continue his education, eventually attending the

University of Chicago thanks to a series of scholarships and a

succession of jobs as varied as janitor and jingle-contest judge.

After college, he studied acting with Lee Strasberg in

New York, but learning the Method theory of acting didn’t

land him a job, and he returned to Chicago with as little act-

ing experience as when he left. Back in his hometown, how-

ever, he teamed up with friends Barbara Harris, Paul Sills,

ALAN ARKIN

, and

ELAINE MAY

and began an improvisational

theater group that performed for three straight years at

Chicago’s Compass club.

In the late 1950s, Nichols and May began their two-per-

son comedy act, which culminated in a hit Broadway show in

1960, An Evening With Mike Nichols and Elaine May. The

team broke up in the early 1960s, and Nichols eventually

took a stab at directing for the theater, making his debut with

NEIL SIMON

’s Barefoot in the Park in 1963. The show was a

smash hit, and Nichols directed six more plays consecutively,

all of them major hits.

His success on Broadway made it inevitable that he would

be asked to direct a movie. The first film he agreed to direct

was The Graduate (1967), but he delayed production on that

movie when he had the opportunity to direct Who’s Afraid of

Virginia Woolf? (1966). The film based on the Edward Albee

play is judged by many to be the best movie that

ELIZABETH

TAYLOR

and

RICHARD BURTON

ever starred in together. For

his part, Nichols came away with both a box-office winner

and an Oscar nomination for Best Director.

The Graduate became an even more successful movie. It

was one of the biggest grossers of the 1960s, earning in excess

of $60 million. It made Dustin Hoffman a star and brought

Nichols the Best Director

ACADEMY AWARD

and a nomina-

tion for Best Picture.

With the clout that came from two previous hits, Nichols

was given an $11 million budget to direct the movie version

of Joseph Heller’s Catch-22 (1970), a novel that was generally

considered unfilmable. The result was a flawed masterpiece.

Equally ambitious was Carnal Knowledge (1971), a film about

sexual and social relationships that showed its audience no

quarter; it was a provocative and extremely controversial

movie that proved to be popular, as well.

Nichols seemed to pull back from tough-minded film-

making to direct The Day of the Dolphin (1973), The Fortune

(1975), and Gilda Live (1980), but he returned to more

socially conscious content when he took on Silkwood (1983),

a film based on the true story of a whistle-blower in a nuclear

power plant.

In recent years, Nichols has began to direct movies not

unlike his earliest film efforts. Heartburn (1986) and Biloxi Blues

(1988) are both about love relationships, the first about one

that doesn’t work out, the second about the youthful hope that

one will. In addition, his touch for social comedy is as sure as

ever, as evidenced by his direction of Working Girl (1988) for

which he received an Oscar nomination for Best Director.

Nichols went on to make some star-studded pictures dur-

ing the 1990s, such as Postcards from the Edge (1990, with

MERYL STREEP

and

SHIRLEY MACLAINE

), Regarding Henry

(1991, with

HARRISON FORD

), and Wolf (1994, with

JACK

NICHOLSON

), but these films were relatively disappointing at

the box office. Nichols recovered considerable clout, how-

ever, with his The Birdcage (1996, with

ROBIN WILLIAMS

and

Broadway star Nathan Lane). Following this triumph,

Nichols turned to acting in the stage production of The Des-

ignated Mourner, later made into a film in 1997. His next film,

Primary Colors (1998), starring

JOHN TRAVOLTA

and Emma

Thompson, was a critical success, but failed at the box office.

In the year 2000, Nichols delivered What Planet Are You

From?, which did little to help his reputation, but, once again,

the resilient Nichols returned to form with the cable film Wit

(2001), starring Emma Thompson, and he received an Emmy

Award for his direction.

Nicholson, Jack (1937– ) An actor who has made an

art out of playing alienated loners. He has been a major star

of offbeat, intelligent movies since emerging from relative

obscurity in a supporting role in Easy Rider (1969). The oft

Oscar-nominated Nicholson had a fascinating decade-long

film career before being discovered by the critics and the

mass audience, during which time he acted, wrote screen-

plays, directed, and even produced low-budget movies. Like

ROBERT DE NIRO

, Nicholson has been willing to change his

appearance radically from film to film, even if it means look-

ing distinctly unstarlike. Also like De Niro, superstar Nichol-

son has been open to playing supporting roles in films that

have offered him meaty scenes.

NICHOLS, MIKE

296

Born to an alcoholic father who abandoned his family

before he was born, Nicholson was raised by his grandmother,

who owned a New Jersey beauty parlor. Unlike many modern

actors who received their early training in college, Nicholson

never got past high school. He drifted into the movies while

visiting his mother in Los Angeles when he was just 17 years

old. His first job in the film industry was working as a gopher

at MGM. Acting appealed to him, and he joined the Players

Ring Theater group and began to study his new craft.

After some minor stage and TV experience, Nicholson

began to appear in the movies, making his film debut in a lead

role in the low-budget

ROGER CORMAN

production The Cry

Baby Killer (1958). Nicholson would continue working on

and off with Corman during the next 10 years. Curiously,

while any number of writer-directors, including

FRANCIS

FORD COPPOLA

,

PETER BOGDANOVICH

, Jonathan Demme,

and others, have emerged from Roger Corman’s school of

cinema hard knocks, Nicholson is the only major acting star

to have done so. Among Nicholson’s Corman-related proj-

ects are The Wild Ride (1960), The Little Shop of Horrors

(1961), The Terror (1963), The Raven (1963), and The St.

Valentine’s Day Massacre (1967). He worked strictly as a

screenwriter for The Trip (1967).

Nicholson didn’t act exclusively for Corman during his

long trek though the cinema wilderness. He was occasionally

seen in small roles in more mainstream films such as Studs

Lonigan (1960) and Ensign Pulver (1964). His real growth,

however, came as a combination actor-screenwriter and

sometime producer, working in collaboration with director-

producer Monte Hellman. Together, they made several inter-

esting cheapie films, among them Flight to Fury (1964), Ride

in the Whirlwind (1966), and The Shooting (1967).

After cowriting and coproducing the rock group the Mon-

kees vehicle Head (1968), Nicholson found himself a last-

minute fill-in for actor Rip Torn, who was supposed to play the

alienated lawyer in Easy Rider. Having acted in more than his

share of low-budget motorcycle/psycho/drug movies, there

was no reason for Nicholson to expect that this film would be

any different from the others. Yet Easy Rider became the huge

sleeper hit of 1969, catapulting Nicholson to the brink of star-

dom with an Oscar nomination as Best Supporting Actor.

A symbol of the youth market, Nicholson was quickly

hired to play a supporting role in the

BARBRA STREISAND

musical On a Clear Day You Can See Forever (1970). The film

was such a bomb that Nicholson has stayed clear of such pon-

derous mainstream vehicles ever since. He had found his

NICHOLSON, JACK

297

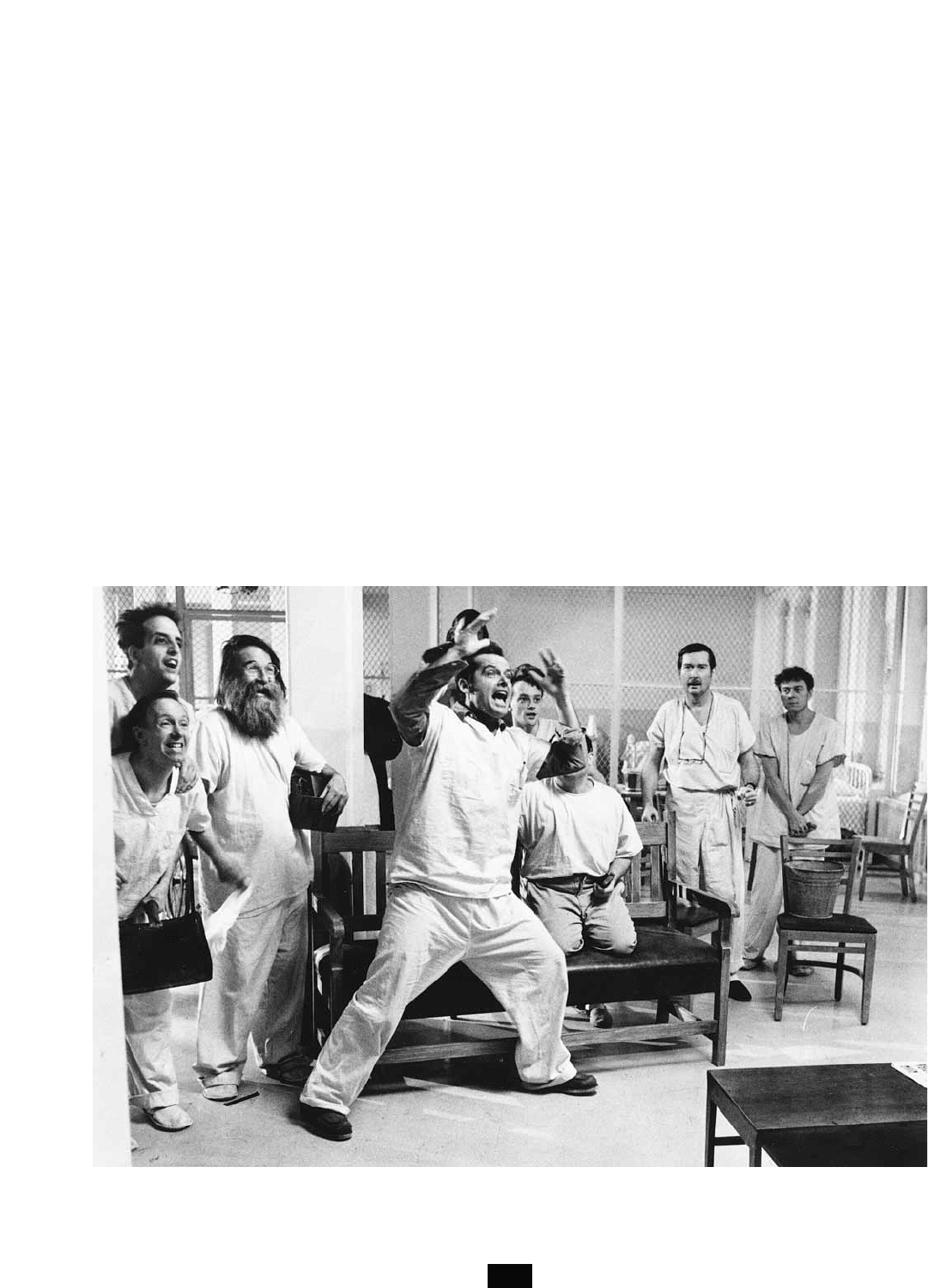

Jack Nicholson (center) in One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)