Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

dancing prowess as he elicits a confession from the “bad guy”

and provides the framed Latifah with her freedom. Martin has

established himself as an outstanding comic who has a creative

mind and a flair for taking on unusual roles.

Marty The 1955 Academy Award-winning movie was the

cinematic version of the

PADDY CHAYEFSKY

story originally

produced for TV. Its success on television prompted its

precedent-making remake on film for theatrical release.

Marty became the sleeper box-office hit of the year, winning

a total of four Oscars.

At first glance, a movie about a shy, lonely, middle-aged

Bronx butcher, Marty, played by

ERNEST BORGNINE

, who

finds love with a plain-Jane schoolteacher (Betsy Blair) would

hardly seem like a sure-fire money-maker, but the sensitively

written screenplay by Chayefsky (who had also written the

teleplay) turned Marty’s tentative attempt to find love into a

universal experience.

The success of Marty caused Hollywood to look to tele-

vision as a source of future films and as a source of talent.

Actors, directors, and writers soon graduated from TV to

movies, in large part thanks to Marty.

The movie’s four Oscars were for Best Picture (Harold

Hecht, producer), Best Director (Delbert Mann), Best Actor

(Borgnine), and Best Screenplay. The movie also was hon-

ored with Best Supporting Actor/Actress nominations for Joe

Mantell and Betsy Blair.

Marvin, Lee (1924–1987) He was the roughest,

meanest, toughest of Hollywood’s heavies during the 1950s.

When he took on heroic roles in the mid-1960s, he was at his

best unleashing the sinister charisma that characterized his

earlier screen successes. With his wolfish grin and deep,

growly voice, Lee Marvin ultimately had as powerful a screen

presence as any other star of the modern era.

Though one might assume from his performances that he

grew up in rough circumstances, Marvin was actually born to

an upper-middle-class family in New York City. His hard-

boiled attitude came from a stint in the Marine Corps during

World War II. After the war, while working as a plumber’s

assistant in summer-stock theater, he found himself filling in

for a sick actor—and so his acting career began.

He studied his craft and worked on the stage in New

York, eventually making his film debut (along with Charles

Buchinski/Bronson) in You’re in the Navy Now (1951). Marvin

worked steadily in the movies, gaining a reputation as an

effective villain. By 1953 he was fourth-billed in the explosive

FRITZ LANG

crime drama, The Big Heat, in which he was at

his vicious best throwing scalding coffee in Gloria Grahame’s

face. When he wasn’t stealing scenes as a heavy, Marvin was

playing corrupt authority figures to the hilt in films such as

the underrated

ROBERT ALDRICH

war movie Attack! (1956).

Marvin was the avatar of villainy as the title character in

John Ford’s masterpiece, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance

(1962). He was the only Hollywood actor of his era who

could have successfully played a heavy to balance the com-

bined heroic status of his two costars,

JOHN WAYNE

and

JAMES STEWART

.

After his Oscar-winning portrayal of twins—one a drunk

and the other a gunfighter with an artificial nose—in the com-

edy western Cat Ballou (1965), Marvin was finally offered more

conventional starring roles. In the best of these roles, Marvin

was only marginally good hearted; his heroic status was rela-

tive to how rotten the other characters were. In films such as

The Professionals (1966), The Dirty Dozen (1967), and Point

Blank (1967), he played characters that were hard and cruel,

but they were fighting for higher ideals in an amoral world.

Marvin’s career was going so well that it seemed as if

nothing could diminish his popularity—until the nonsinging

actor agreed to star (with Clint Eastwood) in the movie musi-

cal version of Paint Your Wagon (1969). The film was a criti-

cal and financial disaster. In retrospect, it marked a turning

point in Marvin’s career. He had some fine roles after that,

such as in Prime Cut (1972) and Emperor of the North (1973),

but even his better films didn’t often succeed at the box

office, and the bad ones were often bombs. The best role of

his later career brought him back to World War II, starring

as a tough sergeant in Sam Fuller’s autobiographical war

movie, The Big Red One (1979).

There were even fewer good roles for the aging tough

guy in the 1980s. In the end, he received more press for his

involvement in a landmark palimony case than for his acting

during the last decade of his life.

Marx Brothers, The The funniest and most influential

comedy team in Hollywood history, their humor paved the

way for such later film comedians as

MEL BROOKS

and

WOODY ALLEN

.

In a mere 13 films, only a handful of which were consis-

tently good from beginning to end, the Marx Brothers—

Groucho, Chico, Harpo, and (in their first five movies)

Zeppo—were a veritable comedy attack force, slinging a

wild, anarchic style of humor at movie audiences, the likes of

which they had never experienced. Their movies’ plots, weak

as they are, are of small concern; the real attractions of any

Marx Brothers film are Groucho’s rapid-fire punning and his

ever-present leer, Chico’s lame Italian accent and his inven-

tive piano playing, and Harpo’s silent lechery and his coat

that hides all manner of things.

Chico (1891–1961), born Leonard Marx, acquired his

nickname from a strong and persistent interest in “chicks”;

Harpo (1893–1964), born Adolph Marx, came by his nick-

name from his playing the harp; Groucho (1895–1977), born

Julius Marx, picked up his nickname as a result of his moody

behavior; Zeppo (1901–79) was Herbert Marx until, accord-

ing to Harpo, he picked up his nickname from constantly

doing chin-ups like “Zippo,” a popular monkey act in vaude-

ville; and a fifth brother, Gummo (1893–1977), born Milton

Marx, was tagged with his nickname because he wore gum-

soled shoes. Gummo, however, left the act early on and never

appeared in any Marx Brothers film.

The boys were the children of a poor tailor, Sam Marx,

and an aggressive mother, Minnie Marx, who pushed her kids

MARTY

268

into show business with the considerable help of her brother,

vaudeville star Al Shean, of the team of Gallagher and Shean.

The brothers’ individual comic personalities evolved over

a long stretch spent in vaudeville. Harpo’s mute clown, for

instance, was the result of an act written by their Uncle Al in

which Harpo was given but three lines. In a review of the act

published the day following its opening, a local critic wrote

that Harpo was brilliant as a mime, but that the magic was

lost when he spoke. Harpo never spoke in character again

(except for a sneezed “achoo” in At the Circus (1939).

When the Marx Brothers arrived on Broadway in a

loosely written play called I’ll Say She Is in 1924, the knock-

about vaudevillians suddenly became the toast of the Great

White Way. A year later they opened in The Cocoanuts, a play

written for them by George S. Kaufman and Morrie Ryskind,

with music and lyrics by

IRVING BERLIN

. The play was

another hit and was eventually filmed in Astoria, Queens,

even while the team was performing in another hit play, Ani-

mal Crackers.

Paramount put the Marx Brothers under contract, releas-

ing The Cocoanuts in 1929 and Animal Crackers in 1930. The

latter film contained the tune that would become Groucho’s

theme song, “Hooray for Captain Spaulding.”

The brothers made three more films for Paramount, all of

them in Hollywood. These included Monkey Business (1931)

and the hilarious send-up of higher education, Horsefeathers

MARX BROTHERS, THE

269

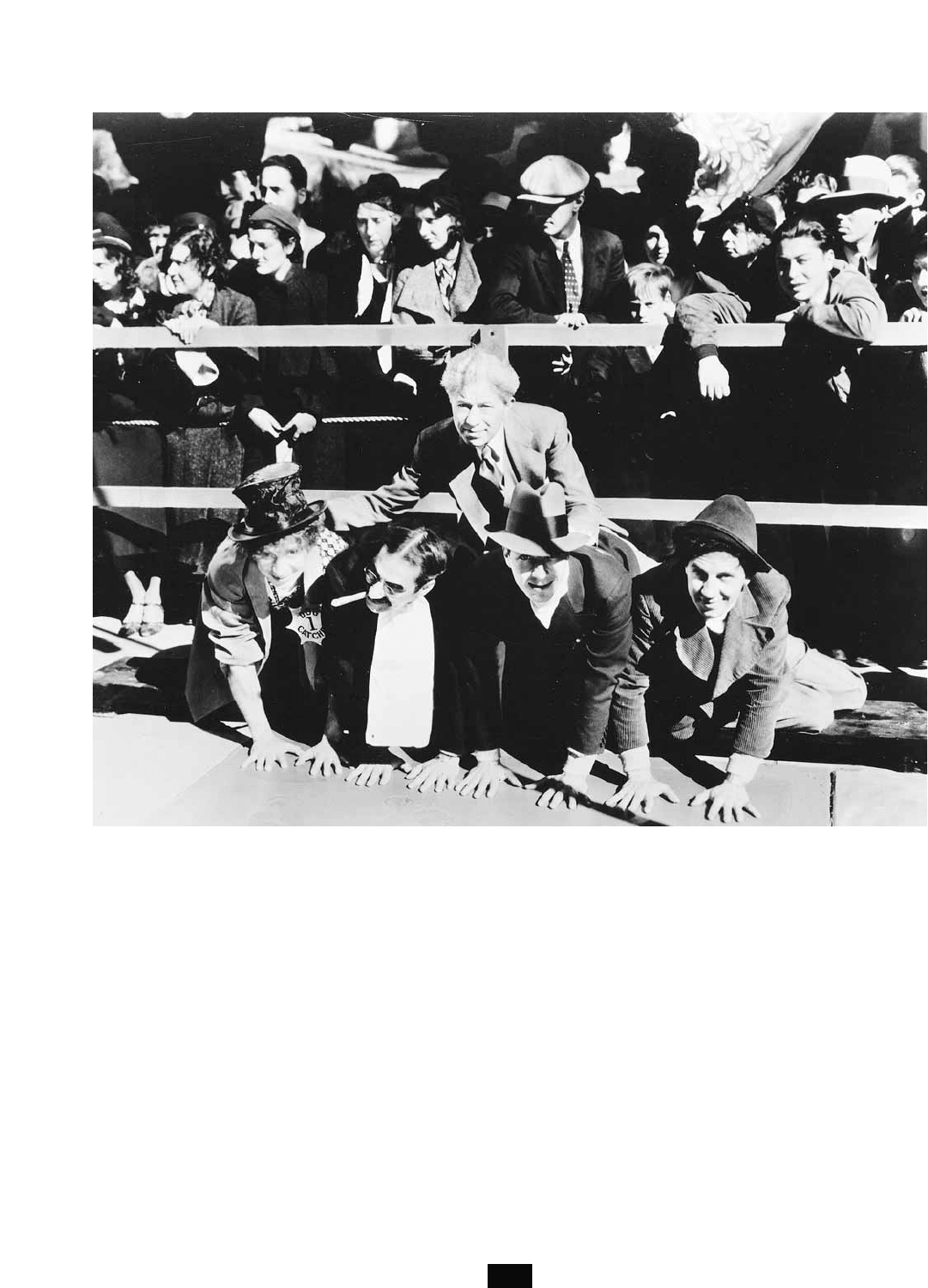

The Marx Brothers (from left to right), Harpo, Groucho, Zeppo, and Chico, have long been cult favorites, but they were

also heralded in their own time, as evidenced by the hoopla over their making hand prints in cement at what was then

Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood. Sid Grauman, the famous movie exhibitor, looks on.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF

THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

(1932), followed by Duck Soup (1933), in which the team

turned politics and the institution of war into sheer hilarity.

These last two films are arguably their finest.

Unfortunately, Duck Soup was not a rousing success at the

box office. Paramount chose not to renew the Marx Brothers’

contract, and Zeppo quit the team to become a theatrical

agent. Though Paramount no longer wanted the Marx

Brothers,

IRVING THALBERG

at MGM did. He proposed,

however, that they be paid 25 percent less than before

because Zeppo had quit the team. Groucho retorted that

they were twice as funny without Zeppo; Thalberg relented

and a deal was struck. In any event, Margaret Dumont, who

played the perfect dowager foil to Groucho in seven Marx

Brothers movies, was ultimately more important to their

films than Zeppo ever was.

Believing the brothers to be actually too funny, Thalberg

sought to slow their movies down and attract a female audi-

ence by adding a love interest. He also thought it would be a

good idea for the boys to take their comic bits out on the road

to hone them for their pictures. The result of Thalberg’s

brainstorm was A Night at the Opera (1935), the most com-

mercially successful of the Marx Brothers’ movies. A Day at

the Races (1937) was only a slightly lesser follow-up, but MGM

seemed to lose interest in the team after Thalberg died, and

their films were soon beset by sillier romantic subplots.

Nonetheless, there were still wonderful moments in their

movies, particularly in At the Circus (1939) and Go West (1940).

Among other later movies were the film version of the hit

play Room Service (1938), The Big Store (1941), an independ-

ent production of A Night in Casablanca (1946), and Love

Happy (1949), the team’s last movie together and the only one

in which Harpo had top billing. Love Happy also featured

future female superstar

MARILYN MONROE

and was produced

by the first female superstar,

MARY PICKFORD

.

The Marx Brothers never made another movie together as

a team after Love Happy—though they each appeared in sepa-

rate segments of the all-star film The Story of Mankind (1957).

Of the three brothers, only Groucho remained fully active in

show business. In addition to his hit radio and TV series, Yo u

Bet Your Life during the 1950s, he also appeared solo in several

films, including the Carmen Miranda vehicle Copacabana

(1947), Double Dynamite (1951) with Jane Russell, A Girl in

Every Port (1952), and, finally, Skidoo (1969). Groucho also

cowrote a screenplay with Norman Krasna for The King and

the Chorus Girl (1937), a film starring

JOAN BLONDELL

.

See also

AGENTS

;

COMEDY TEAMS

;

DUCK SOUP

.

Mason, James (1909–1984) An actor with one of the

richest, most evocative speaking voices in the history of the

cinema. A one-time matinee idol in England, he came to

Hollywood in the late 1940s but never became the superstar

that many predicted. Though he had a number of triumphs,

particularly in the early 1950s, he eventually became a reli-

able and highly valued character actor. In his later years, his

smooth acting style and mellifluous voice brought him a

measure of the fame and praise that had eluded him in ear-

lier decades.

Born in England and educated as an architect, he

nonetheless chose a career in the theater, making his debut in

The Rascal in 1931. He continued acting on the stage

throughout the 1930s and the very early 1940s, but he was

one of the few stage-trained actors who publicly professed to

prefer the camera to the boards. He began to work in film in

the mid-1930s, starring in a number of low-budget English

movies, the first of which was Late Extra (1935). His first

important film role was a small part in Alexander Korda’s Fire

over England (1937).

Clearly interested in pursuing a movie career, however,

Mason helped produce and script his own starring vehicle on

a shoestring budget called I Met a Murderer (1939). The crit-

ics liked the film, but it didn’t go over well with the public.

Mason would later produce several films on his own, none of

them commercial hits.

By 1941 he had begun to act in films full time, making his

big breakthrough in The Man in Grey (1943). Mason special-

ized in playing hard-hearted men who treated their women

badly but were redeemed by the end of the movie. Women

moviegoers couldn’t get enough of his handsome young man

who was such a rotter. During the next three years he became

England’s most popular movie star. He made his reputation

as a serious actor in a top-notch drama, Carol Reed’s Odd

Man Out (1947).

Hollywood wanted Mason. He arrived in America in

1947 but was unable to act on film in the United States by

court order due to contractual problems. He was forced to

bide his time. Unfortunately, it was time ill spent: He went

on to flop in a Broadway show and made inadvertent unkind

remarks about the American film industry that were made

public. By the time he starred in his first Hollywood vehicle,

Caught (1949), he was tarnished goods.

Mason struggled along in mediocre movies, his stock

diminishing every year, until he had a short streak of strong

roles in good movies, most notably in The Desert Fox (1951),

Five Fingers (1952), and in Joseph Mankiewicz’s highly

regarded all-star version of Julius Caesar (1953), in which he

had perhaps the greatest role of his career, Brutus. His most

famous role, however, was that of the fading star, Norman

Maine, in

GEORGE CUKOR

’s A Star Is Born (1954). The film

was obviously a

JUDY GARLAND

vehicle, but Mason was the

character who held the emotional center of the story. Origi-

nally,

HUMPHREY BOGART

was slated for the part and, later,

CARY GRANT

actually signed to play Norman Maine, but

when the dust settled Mason ended up with the meaty role,

winning an Oscar nomination for Best Actor.

Mason went on to play challenging roles in only a hand-

ful of notable films from then on. He was memorable as a

victim in

NICHOLAS RAY

’s Bigger than Life (1956), as the vil-

lain in

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

’s North by Northwest (1959),

and, in a tour de force that should have resurrected his fad-

ing fortunes, as Humbert Humbert in

STANLEY KUBRICK

’s

Lolita (1962).

After several flops, however, Mason had become solidly

entrenched in supporting character parts—many of them in

English films. Though his roles were smaller, at least his

films were good, as were his reviews. Among his better films

MASON, JAMES

270

during that era are The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964), The

Pumpkin Eater (1964), Lord Jim (1965), The Blue Max (1966),

and Georgy Girl (1966).

His film choices became considerably more indiscrimi-

nate in the later 1960s and throughout the rest of his career;

he was an actor who simply kept working, regardless of the

material. Still, there were a number of good films amid the

schlock. The best of them were The Last of Sheila (1973), 11

Harrowhouse (1974), Voyage of the Damned (1976), Heaven Can

Wait (1978), The Boys from Brazil (1978), The Verdict (1982),

and The Shooting Party (1984), his final film.

master shot An entire scene photographed from begin-

ning to end as recorded by a single camera and without any

edits. Although the master shot may be used in a film exactly

as it is photographed, it is more often intercut with close-ups,

reaction shots, and the like, all of which are photographed

separately to correspond to the master.

For example, a master shot of a typical gunfight in a west-

ern might have the camera recording the scene from slightly

behind the hero and off to his right. Whether the camera

itself moves or not, the film must run continuously as the

hero and villain approach each other, size each other up, then

draw and shoot their guns, with (let us suppose) the bad guy

crumpling to the ground. If the director likes this particular

take, he or she has a master shot.

The director might then establish new set-ups and roll

the cameras again to get close-ups of the two characters’

facial expressions as they approach each other. The director

might also choose a subjective shot capturing one gunman

from the other’s point of view, as well as a close-up of a hand

reaching for a gun. Finally, the director might have a medium

close-shot of the villain as he falls to the ground. All of these

scenes would be carefully shot so as to “match” the visual

information recorded on the master; otherwise the fully

edited scene would be full of visual inaccuracies.

Matthau, Walter (1920–2000) A late-blooming star,

Matthau came to prominence in the latter half of the 1960s,

specializing in comedy but equally adept in action and the

occasional romantic role. With his beat-up-looking face and

body, a shuffling gait, and a decidedly ethnic-sounding vocal

quality, Matthau hardly seemed a candidate for movie star-

dom, but thanks to an abundance of talent, the right roles,

and a receptive audience, he became a top box-office attrac-

tion and an Oscar-winning performer.

Born Walter Matuschanskayasky to a former Catholic

priest and his Russian Jewish wife, Matthau grew up in

poverty on New York City’s Lower East Side. His job at the

age of 11 of selling soda in a Yiddish theater during intermis-

sion led to his acting on stage in bit parts.

After serving in the air force as a gunner, Matthau stud-

ied acting on the G.I. Bill at the New School’s Dramatic

Workshop. With his peculiar mug, he seemed best suited for

character parts, and he played them with ever-increasing suc-

cess on stage until he made his film debut in The Kentuckian

(1955). He played the villain—as he would in virtually all of

his films during the next decade.

Matthau worked constantly from 1955 to 1965, appear-

ing on Broadway, starring in a short-lived TV series, Talla-

hassee 7000 in 1959, and playing bad guys in the movies, most

memorably in A Face in the Crowd (1957), King Creole (1958),

and Charade (1963). He even directed himself in a film, a low-

budget affair called Gangster Story (1958).

A highly respected actor, Matthau merely needed the

right vehicle to show off his abilities. Director

BILLY WILDER

wisely cast Matthau in his black comedy The Fortune Cookie

(1966). Matthau’s brilliant performance as a sleazy ambu-

lance-chasing lawyer brought him a Best Supporting Actor

Academy Award. He also came away with a lasting personal

and professional relationship with his costar

JACK LEMMON

.

Playwright-screenwriter

NEIL SIMON

provided Matthau

with another important vehicle, penning the role of Oscar

Madison in the play The Odd Couple expressly for him. The

critical and public response to his performance as Madison

made Matthau an undisputed star, at least in New York, and

when he later reprised the role in the film version of the play

in 1968 (costarring with Lemmon), he solidified his standing

as a major comic film talent. Simon has since provided a

great many other excellent roles for Matthau in such films as

Plaza Suite (1971), The Sunshine Boys (1975), which garnered

him one of his two Best Actor Oscar nominations, and Cali-

fornia Suite (1978). Jack Lemmon directed him in Kotch

(1971), for which Matthau received his other Oscar nomina-

tion as Best Actor.

Matthau’s portrayal of a modern-day

W

.

C

.

FIELDS

play-

ing cranky comic characters led to either critical or commer-

cial success in such films as A New Leaf (1971), The Bad News

Bears (1976), and Little Miss Marker (1979). Having proved

himself in comedy, Matthau also exhibited a wider range of

acting talent. He first showed his dramatic potential in the

seriocomic film Pete ’n’ Tillie (1972). His next three films

were pure action movies, all well reviewed, and all of them

hits: Charley Varrick (1973), The Laughing Policeman (1973),

and The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974). In yet

another display of versatility, Matthau, then in his late fifties,

starred in House Calls (1978), a light romance with Glenda

Jackson. The film was such a hit the pair was reunited in

another romantic comedy, Hopscotch (1980).

Due to ill health, Matthau appeared with less frequency

in the movies during the 1980s—and also with less commer-

cial success than in the past. Despite generally good personal

notices, films such as First Monday in October (1981), Buddy,

Buddy (1981), The Survivors (1983), and The Couch Trip (1988)

were not hits.

Aside from a television appearance in 1989 as a lawyer in

The Incident (1989) and a bit part in

OLIVER STONE

’s JFK

(1991), Matthau did not appear in a film between 1987 and

1993, when he and Jack Lemmon were reunited in Grumpy

Old Men. The duo continued their bickering and sparring as

they fought for Ann-Margret’s affections; in 1995’s sequel,

they were Grumpier Old Men, this time with Sophia Loren as

the love interest. In fact, the Matthau-Lemmon team would

appear in more films (Out to Sea [1997] and Neil Simon’s The

MATTHAU, WALTER

271

Odd Couple [1998]), but the material became increasingly

stale. Matthau seemed to be at his best playing a grump, and

he was the inevitable choice to play Mr. Wilson in Dennis the

Menace (1993). In I’m Not Rappaport (1996), Ossie Davis filled

in for Lemmon in another geriatric donnybrook. In two sup-

porting roles Matthau was outstanding: He portrayed Albert

Einstein in I.Q. (1994), a romantic comedy, and in Hanging

Up (2000) he played an elderly show-business veteran, mod-

eled after Henry Ephron.

Mature, Victor See

SEX SYMBOLS

:

MALE

.

May, Elaine (1932– ) An actress, writer, and director

specializing in humorous subjects, she was one of the first

women in the modern Hollywood era to write and direct

major motion pictures. Unfortunately, her career took a seri-

ous tumble in 1987 due to her direction of the failed Ishtar,

the biggest bomb of the late 1980s.

Born Elaine Berlin to a theatrical family, she performed

in several plays in the Yiddish Theater with her father, Jack

Berlin. While at the University of Chicago, she met

MIKE

NICHOLS

, another aspiring young actor, and the pair formed

a comedy team that proved to be enormously popular during

the 1950s. The act broke up in 1961 and May began to write

and direct for the theater, though she soon found herself

temporarily drawn back into performing, appearing in Luv

(1967) and Enter Laughing (1967).

During the 1970s May was one of a rare breed: a female

screenwriter and director. She wrote the script of Such Good

Friends (1971) under the pen name Esther Dale and wrote,

directed, and starred in the hit comedy movie, A New Leaf

(1971). When she followed that success with yet another hit,

The Heartbreak Kid (1972), directing her daughter, Jeannie

Berlin, to a Best Supporting Actress nomination, it appeared

as if May were going to become a major new directorial

force. But her next film, Mikey and Nicky, went considerably

overbudget (presaging her greatest disaster), spent years

being edited, and didn’t arrive on movie screens until 1976.

It was not a success.

In 1978, she cowrote the smash hit Heaven Can Wait and

stepped in front of the cameras again in California Suite, but

she was little heard from again until she directed

WARREN

BEATTY

and

DUSTIN HOFFMAN

in the colossal flop Ishtar

(1987). A comedy that went stupendously over budget, it was

ripped apart by the critics and ignored by audiences despite

the film’s star power. Beatty and Hoffman took a lot of the

critical heat for the disaster, but Elaine May’s reputation suf-

fered a terrible beating nonetheless. Ishtar proved very dam-

aging for May, who appeared in only one more film, In the

Spirit (1990), and never directed another movie.

Mayer, Louis B. (1885–1957) The studio chief at

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, the famous film company that bore

his name. Like all the Hollywood moguls, he was a ruthless,

demanding executive with a paternalistic style of doing busi-

ness. As John Douglas Eames has noted in The MGM Story,

Mayer saw his studio as a family, with himself as the patriarch.

He therefore treated everyone beneath him—and there were

as many as 6,000 employees at the studio—like children.

Born in Minsk, Russia, Mayer grew up in Canada after his

family immigrated there when he was still very young. He

was no sooner out of elementary school when he joined his

father’s scrap metal business, eventually opening a similar

business of his own in Boston. Successful, Mayer put his

profits into a failing movie theater, managing to turn it into a

money-making proposition. He soon bought other theaters

until he owned New England’s largest chain of movie houses.

A powerful exhibitor in the growing film business, Mayer

then involved himself in the distribution of movies, becom-

ing an officer of Metro Pictures until he resigned to form his

own production company in 1917. His first film under the

banner of Louis B. Mayer Pictures was Virtuous Wives (1918).

Mayer continued to make movies but was one of the

smaller players in a business that was beginning to solidify

into larger concerns. His company was finally bought in 1924

by Loew’s, Inc., which added the studio to two recent pur-

chases to form Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Mayer’s company

was bought by Loew’s largely to obtain the business acumen

of its president. Mayer was quickly made vice president and

general manager of the new MGM.

Mayer’s influence as studio chief was muted by the

acknowledged brilliance of

IRVING THALBERG

, MGM’s head

of production, who received most of the credit for the studio’s

better offerings during the latter 1920s and early 1930s. But

after Thalberg died, Mayer put his own stamp on MGM’s

films, turning the company toward wholesome family films

such as the Andy Hardy series that starred

MICKEY ROONEY

.

Although virtually all of the Hollywood moguls were

tyrannical, Mayer was the most visible of the pack due to his

station as the head of the most powerful studio, and his com-

pensation reflected his power and influence—he earned more

than $1.25 million per year, making him the highest-paid

executive in America.

In 1951, with revenues falling at MGM and across all of

Hollywood due to the inroads of television, Mayer was finally

replaced by his assistant, Dore Schary. The mogul went on to

become a consultant to Cinerama before making a desperate

attempt to regain his job at MGM via a stockholder insur-

rection. His bid failed, and he died the following year.

See also

METRO

-

GOLDWYN

-

MAYER

.

Maynard, Ken (1895–1973) An exciting cowboy star

who was arguably the greatest trick rider ever to appear in

WESTERNS

. He is also noteworthy for being the original

singing cowboy, introducing musical interludes into his films

in the early 1930s, several years before the advent of the king

of the singing cowboys,

GENE AUTRY

, whom Maynard intro-

duced in In Old Santa Fe (1934). Maynard became a star in

the late 1920s and the early 1930s, his career lasting into the

1940s. His remarkable horse, Tarzan, was nearly as famous as

he was; the animal even starred in his own movie, Come on

Tarzan (1932).

MATURE, VICTOR

272

Maynard, like so many of his fellow cowboy stars, was a

former rodeo champion. He started to appear in bit parts in

westerns in 1923, quickly rising in popularity thanks to his

daredevil stunt riding, so similar to that of the hugely suc-

cessful

TOM MIX

. By the end of the 1920s, Maynard was a

major western star, having made such hit films as Gun Gospel

(1927) and Wagon Master (1929).

The years 1929 to 1934 marked the peak of Maynard’s

career. He often wrote, produced, directed, and starred in his

own “B” movies, among them Sons of the Saddle (1930) in

which he sang for the first time, King of the Arena (1933), and

Gun Justice (1933).

Unfortunately, Maynard had a severe drinking problem

that undermined his ability to perform. His younger brother,

Kermit Maynard, sometimes doubled for him, before becom-

ing a serviceable “B” movie western star in his own right in

the mid-1930s.

Ken Maynard continued to work in low-budget westerns

until the end of the 1930s. After making personal appear-

ances at rodeos in the early 1940s, he returned briefly to Hol-

lywood to make a handful of additional minor horse operas,

such as Arizona Whirlwind (1944). But the magic was gone.

So was Tarzan; the horse had died in 1940.

Maynard was all but forgotten when he was given a bit part

in the low-budget Bigfoot (1971). Soon thereafter, though, his

drinking caught up to him, and he was put in the Motion Pic-

ture Country Home. He died of stomach cancer in 1973.

Mazursky, Paul (1930– ) A one-time actor, he has

become a writer-director-producer sharply attuned to popu-

lar taste, infusing his usually comic films with trenchant

observations on our times. Sometimes criticized for merely

skimming the surface of timely issues, it would be fair to say

in Mazursky’s defense that he is one of the few commercial

filmmakers who is willing to make cultural statements of any

kind in his movies.

Mazursky began to perform while in school and, after

graduation from Brooklyn College, continued to pursue his

career, though with little success. He first appeared on film in

STANLEY KUBRICK

’s Fear and Desire (1953) and later had a

significant role in The Blackboard Jungle (1955). Though he

continued to find occasional roles in films and on TV

throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, he made his first

important breakthrough as a writer, penning sketches for the

high-quality comedy/variety TV series, The Danny Kaye

Show. His writing credits helped him sell his first screenplay

(written in collaboration with his early writing partner, Larry

Tucker), I Love You, Alice B. Toklas! (1968).

Given a chance to direct his own script (written with

Larry Tucker), Mazursky hit a home run his first time up

with his lively comedy about wife-swapping, Bob & Carol &

Ted & Alice (1969). The film didn’t quite have the courage of

its convictions, but it dealt with what was still a shocking sub-

ject for a Hollywood comedy in the late 1960s.

Averaging a film every two years since his debut as a

director, Mazursky has seriously flopped only when he has

been either obviously autobiographical or pretentious.

Among his critical or box-office failures are Alex in Wonder-

land (1970), Next Stop, Greenwich Village (1976), Willie and

Phil (1980), and The Tempest (1982). None of these films,

however, are disasters—Mazursky has the uncanny ability to

make even his poor films interesting.

He began to produce as well as write and direct his

movies with his third film, Blume in Love. It was with this

movie that he hit his stride, establishing an intimate visual

style. He followed that success with the warm yet unsenti-

mental Harry and Tonto (1974). His biggest success of the

1970s was the seriocomic An Unmarried Woman (1978).

Mazursky was the first mass-market filmmaker to focus on

the social and emotional upheaval divorce can inflict on

women. The film was nominated for a Best Picture Oscar.

During the 1980s, Mazursky has excelled as a director of

comedies, making several critical and commercial hits,

including Moscow on the Hudson (1984) and Down and Out in

Beverly Hills (1986), as well as the less successful Moon Over

Parador (1988). Mazursky also directed Enemies: A Love Story

(1989), Scenes from a Mall (1991), The Pickle (1993), and

Faithful (1996).

Mazursky, it should be noted, is a student of the cinema.

A number of his films have been based on foreign film clas-

sics. For instance, his Willie and Phil is an American version

of François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim (1961), and Down and Out

in Beverly Hills is similar to Jean Renoir’s Boudu Saved from

Drowning (1932).

Interestingly, the acting bug still bites the director. In

addition to appearing occasionally in small roles in other

directors’ films, such as A Star Is Born (1976), Mazursky is

visible in small roles in many of his own films, including Alex

in Wonderland, Blume in Love, An Unmarried Woman, Down

and Out in Beverly Hills, and Moon over Parador. In the latter

film, he played

RICHARD DREYFUSS

’s mother. As a director

who loves acting, Mazursky has been able to elicit top-notch

performances from the stars of his films, many of whom have

done some of the best acting of their careers with him,

including Jill Clayburgh, Richard Dreyfuss, Bette Midler,

NATALIE WOOD

, and

ROBIN WILLIAMS

. Other parts have

included performances in Enemies: A Love Story (1989), Scenes

from a Mall (1991), Carlito’s Way (1993), The Pickle (1993),

Miami Rhapsody (1995), Faithful (1996), Crazy in Alabama

(1999), and Do It for Uncle Manny (2002).

McCarey, Leo (1898–1969) A director, screenwriter,

and producer who, at the height of his career in the late 1930s

and early 1940s, found an ideal balance between humor and

sentiment, creating a string of memorable hit movies.

McCarey’s background was rather unusual for a director

who started in the silent era. Many early movie directors had

backgrounds either in engineering or the theater, but

McCarey had been a lawyer—a bad one. He once told

PETER

BOGDANOVICH

that he had been literally chased out of a

courtroom by one of his clients, and he kept on running until

he reached Hollywood in 1918. He received his training in

the early 1920s as an assistant to director

TOD BROWNING

.

He was given the opportunity to direct his first feature film

McCAREY, LEO

273

at

UNIVERSAL PICTURES

, Society Secrets (1921). Unfortu-

nately, the young director wasn’t quite ready to handle such a

responsibility, and the movie was a dismal failure.

During the balance of the 1920s—from 1923 through

1929—McCarey wrote, supervised production, and directed

comic short subjects at the Hal Roach Studio, gaining expert-

ise as a gag man and learning how to fashion cinematic com-

edy. During those years, he either wrote, directed, or

supervised the production of Laurel and Hardy’s greatest

shorts, including their classic, Big Business (1929).

McCarey took a second stab at feature-film directing in

1929 with a minor effort called The Sophomore. This time, he

passed muster and continued directing feature films until

1962. There was nothing special about his earliest work until

he began to direct comedy stars such as

EDDIE CANTOR

in

The Kid From Spain (1932), the

MARX BROTHERS

in

DUCK

SOUP

(1933), and

MAE WEST

in Belle of the Nineties (1934). He

directed a different kind of star in 1935 when he chose

CHARLES LAUGHTON

as the lead in Ruggles of Red Gap. The

film was a critical and box-office hit, firmly establishing

McCarey as a director of note.

After a noble but failed attempt at resurrecting

HAROLD

LLOYD

’s career with The Milky Way (1936), McCarey went on

to produce and direct the most unflinchingly honest film ever

made in the 1930s about the American family and the Great

Depression. The movie was Make Way for Tomorrow (1937),

and it had surprisingly good humor despite its heart-wrench-

ing story of an aging couple who lose their home and dis-

cover that their grown children are either unwilling or unable

to help them live the last few years of their lives together.

The two old people are parted forever in one of Hollywood’s

most haunting film endings.

Beginning with Make Way for Tomorrow, McCarey pro-

duced every movie he directed save one, and from 1939

onward, he either supplied the stories for his own films or

cowrote the screenplays. For a solid decade, he had hit after hit.

He started his hit parade after Make Way for Tomorrow

with a delightful screwball comedy starring

CARY GRANT

and

IRENE DUNNE

, The Awful Truth (1937), a movie that boldly

and quite comically dealt with the issue of divorce. McCarey

won an Academy Award as Best Director for 1937, ostensibly

for The Awful Truth but most likely because he had shown

such remarkable directorial range that year.

He showed still more range when he directed his most

lushly romantic movie, Love Affair (1939), a film rarely seen

today because McCarey remade it himself in 1957 as An

Affair to Remember and the earlier version was removed from

circulation. Those who have seen both consider Love Affair

the superior film.

McCarey’s career was building to a high point when he

made Once upon a Honeymoon (1942). He reached the apex

when he directed Going My Way (1944), starring

BING

CROSBY

. The movie was a spectacular hit, and McCarey won

Academy Awards for his story and for his direction. He fol-

lowed that success with a sequel to Going My Way, The Bells

of St. Mary’s (1945), and it, too, was a smash hit.

McCarey began to make movies less often, directing only

one in the late 1940s, the moderately successful and sweet-

natured Good Sam (1948), starring

GARY COOPER

. Four years

later, McCarey’s career took a nosedive when he made My Son

John (1952), an incredibly heavy-handed anticommunist film

that is almost unwatchable today. He recouped with An Affair

to Remember in 1957, but McCarey’s humor—his greatest

asset—was sadly lacking in Rally Round the Flag, Boys! (1958),

and the drama was flat in his last film, Satan Never Sleeps (1962).

McCrea, Joel (1905–1990) In a career spanning five

decades, he is best remembered as an agreeable light comic

actor who had his heyday in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

In the early 1930s, he usually had the less important male

lead opposite bigger female stars. From the mid-1940s until

his retirement, he appeared almost exclusively in westerns.

But whatever he played in, Joel McCrea’s easy, likable man-

ner made him a bankable if not altogether exciting film star

throughout his career.

McCrea grew up in southern California and set his sites

on the movie business from a very early age. He pursued the-

ater in college and acted in local community productions, all

the while working as an extra in Hollywood whenever he got

the chance.

He found his first nonextra role in The Jazz Age (1929)

and proceeded to work at many of the major studios, princi-

pally MGM, RKO, and Goldwyn, during the 1930s. McCrea

made a lot of movies, some of them of reasonable quality, but

nothing that made him stand out. Even when he starred in

the

WILLIAM WYLER

classic

DEAD END

(1937), he was

upstaged by

HUMPHREY BOGART

cast in a lesser role. That

same year, however, he starred in his first western, Wells Fargo

(1937), and carried the film, turning it into a major hit. Union

Pacific (1939) ensured his standing as a credible western star.

The early 1940s brought McCrea his highest level of pop-

ularity. He showed his dramatic range as an actor in

ALFRED

HITCHCOCK

’s Foreign Correspondent (1940) and then teamed

up with

PRESTON STURGES

at Paramount in that director’s

golden period, starring in the delightful comedies Sullivan’s

Travels (1941) and Palm Beach Story (1942), as well as the lesser

Sturges comedy/drama, The Great Moment (1944).

Beginning in 1946, McCrea acted almost exclusively in

westerns, none of which are worth mentioning other than

SAM PECKINPAH

’s highly regarded Ride the High Country

(1962). As an aging lawman with nothing left but his princi-

ples, McCrea was truly superb. Nonetheless, his costar,

RAN

-

DOLPH SCOTT

, stole the picture from him.

McCrea temporarily retired after Ride the High Country,

returning to the big screen just a few more times over the

next two decades in low-budget westerns.

Though generally considered in his day a second-string

GARY COOPER

in action films and a second-string

CARY

GRANT

in contemporary comedies, in his open, honest style,

McCrea was probably closest to

HENRY FONDA

. In any event,

he was a serviceable and attractive actor.

McDaniel, Hattie (1895–1952) A black actress who

breached the color barrier in a number of significant ways in

McCREA, JOEL

274

the film, radio, and TV industries. Limited opportunities for

blacks in films resulted in few roles other than demeaning

stereotypical ones, but McDaniel made the best of a bad sit-

uation, making her presence felt in a great many films from

the 1930s until the early 1950s.

The daughter of a Baptist minister, McDaniel was accus-

tomed to singing in church. She began her show-business

career as a band singer, becoming the first black woman to

perform on radio. She began her acting career in the early

1930s, often in the role of a maid. With her warm, friendly

style, she was often chosen to play in support of sharp-edged

performers such as

MARLENE DIETRICH

(in Blonde Venus

[1932]) and

MAE WEST

(in I’m No Angel [1933]). In the latter

film, she was the recipient of Mae West’s famous line, “Beu-

lah, peel me a grape.”

McDaniel worked steadily in films, often (although not

exclusively) in either contemporary or period pieces that

were set in the South. For instance, she played supporting

roles in Judge Priest (1934), The Little Colonel (1935), Show

Boat (1936), Maryland (1940), and Song of the South (1946).

Her most famous role was in Gone With the Wind (1939), for

which she won an Oscar as Best Supporting Actress, the first

black actor in Hollywood history to be so honored.

McDaniel also acted on radio, appearing on the Eddie

Cantor Show, Amos ‘n’ Andy, and eventually her own show,

Beulah, turned into a TV show in 1952 in which she briefly

held the limelight before her death.

See also

RACISM IN HOLLYWOOD

.

McLaglen, Victor (1886–1959) A big, barrel-chested

former boxer who became a raw, though popular, actor first

in England and then in the United States. McLaglen was a

long-time favorite of

JOHN FORD

who directed him a dozen

times, often giving him a good role just when the actor’s

career needed a shot in the arm. He was a major (if unlikely)

star in the latter 1920s and through most of the 1930s before

he became a serviceable character actor.

McLaglen was born in Great Britain and spent a colorful

youth as a soldier, miner, and professional prize fighter, going

six rounds with the then world heavyweight champion, Jack

Johnson. In 1920, he was spotted in England by a producer

who thought the fighter could make a dashing film star. Cast

in The Call of the Road, a surprise hit, McLaglen suddenly

became a bankable actor. Within just two years, he was one

of England’s biggest stars. But when the bottom dropped out

of the English film market, the actor suddenly found himself

in need of work.

When Hollywood beckoned, McLaglen quickly

responded. His first American feature was The Beloved Brute

(1925), an aptly named movie that also defined the actor’s

film personality. Among his silent films were The Unholy

Three (1925), in which he costarred with

LON CHANEY

; The

Fighting Heart (1925), his first film under the directorial

guidance of John Ford; and What Price Glory (1926), in

which he had his most important silent screen role, playing

Captain Flagg. The latter film made $2 million at the box

office and spawned several sequels with McLaglen good-

naturedly battling his friend Sergeant Quirt (played by

Edmund Lowe).

John Ford directed McLaglen in his first talkie, The Black

Watch (1929), but after a few successes, such as Dishonored

(1931) with

MARLENE DIETRICH

, his career began to fade.

Ford, as always, was there to help him, giving him a starring

role in The Lost Patrol (1934). The film was a hit, and it led

Ford to cast McLaglen in The Informer (1935). McLaglen was

at his boozy, brawling, brutish best, turning his character,

Gypo Nolan, into a sympathetic man tortured by guilt. He

won a Best Actor Oscar for his performance.

The latter 1930s were uneven for McLaglen. He starred

in several pictures and played supporting roles in others. His

best films of this period were Professional Soldier (1936), Wee

Willie Winkie (1937), the Ford-directed

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

film, and the magnificent Gunga Din (1939).

Though McLaglen worked fairly regularly, his career

began a steady slide in the 1940s. He was soon playing vil-

lains in “B” movies. Though he continued to appear in “B”

movies throughout the rest of his life, he did manage to

appear in a handful of quality films, all of them directed by

his friend and protector John Ford. The director cast him as

a tough, hard-drinking but lovable sergeant in Fort Apache

(1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande

(1950). Ford used him again as John Wayne’s foil in The Quiet

Man, although a double stood in for McLaglen in the long

fight scene that concludes the film.

The actor continued to appear in small character parts

throughout the 1950s, and he lived long enough to be

directed by his son, Andrew V. McLaglen, in The Abductors

(1957). He died two years later of a heart attack.

McQueen, Steve (1930–1980) An actor who was the

personification of “cool,” he built his considerable reputation

in the 1960s and 1970s around a macho, loner image. His

weathered good looks made him a sex symbol to women, and

his tough action roles earned him the admiration of men.

McQueen was never considered an accomplished actor

(although he was very effective within his limitations), but he

was every bit the movie star, with a charisma that was unmis-

takable on the big screen. In addition to being one of the

highest-paid actors of the late 1960s and early 1970s, he also

had the distinction of being among the first television stars to

make what was then the very difficult leap to major movie-

star status.

McQueen had a difficult childhood, having been aban-

doned by his father when he was three years old. He spent

much of his youth in trouble, getting the better part of his

education in a reform school. He held a variety of jobs, such

as carnival worker, sailor, and lumberjack, before joining the

marines. He was not the perfect soldier, going AWOL at one

point and spending a portion of his military service in jail.

Directionless and headed for hard times when he left

the marines, McQueen drifted from job to job, making

money as a poker player when all else failed, until an aspir-

ing actress girlfriend suggested he become an actor. He was

accepted at New York’s Neighborhood Playhouse and

McQUEEN, STEVE

275

began to learn his craft there on the G.I. Bill in 1951, later

studying with Uta Hagen.

McQueen had on-the-job training in stock and on televi-

sion. His big break came in 1956 when he replaced Ben Gaz-

zara as the star of the Broadway production of A Hatful of

Rain. That same year he finally broke into the movies in a bit

part in Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956).

He first became known to the mass audience when he was

cast as Josh Randall in the TV series Wanted: Dead or Alive.

He played a bounty hunter in the western action show, and

its success for three and a half years (1958–61) made him a

famous TV personality. McQueen continued to act in movies

and make TV guest appearances during the run of his own

show. For instance, he had the lead role in the low-budget

science fiction film The Blob (1958), and he also appeared in

The Great St. Louis Bank Robbery (1959) and Never So Few

(1959). But the film that suggested he might have a career

beyond television was The Magnificent Seven (1960), in which

he gave a strong supporting performance.

The film industry saw McQueen’s potential and he was

cast in several films in the hope that he’d emerge a star. After

such flops as Hell Is for Heroes (1962) and The War Lover

(1962), he finally clicked in The Great Escape (1963), the film

with which he is still most closely identified.

Again, McQueen’s career stalled with several interesting

failures, among them Love with the Proper Stranger (1963) and

Baby the Rain Must Fall (1965). He finally hit his stride with

The Cincinnati Kid (1965), a poker version of Paul Newman’s

pool-hall saga, The Hustler (1961), and nearly as successful.

(For the rest of McQueen’s career, he and Newman would be

considered Hollywood’s top male action/sex symbols.) The

hits kept coming for McQueen: Nevada Smith (1966), The

Sand Pebbles (1966), for which he won his only Best Actor

Oscar nomination, The Thomas Crown Affair (1968), Bullitt

(1968), and an off-beat comedy, The Reivers (1969).

After The Great Escape, McQueen’s love for motorcycles

and fast cars became well known to film fans. The automo-

tive fast track seemed to suit him in Bullitt, a movie full of

chase scenes, and racing cars were at the heart of Le Mans

(1971), his first major flop as a megastar.

After having made a number of films through his own

production company, Solar Productions, including the Le

Mans fiasco, he decided to join a more powerful organiza-

tion, becoming, in 1971, a founding member of First

Artists, together with

BARBRA STREISAND

,

SIDNEY POITIER

,

and

PAUL NEWMAN

.

DUSTIN HOFFMAN

joined First Artists

the following year, which led to his teaming with McQueen

in Papillon (1973), which was one of McQueen’s last com-

pelling movies. In fact, the early 1970s marked the final

flowering of the actor’s worldwide appeal to film audiences.

He scored with such

SAM PECKINPAH

films as Junior Bonner

(1972) and The Getaway (1972), meeting and later marrying

and divorcing his costar, Ali McGraw. His appearance in the

all-star The Towering Inferno (1974) brought him a stagger-

ing $12 million.

He was off the screen for several years after The Towering

Inferno, returning in 1977 in a film that surprised but did not

delight his fans or the critics, an adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s

An Enemy of the People.

He was again off the screen for several years, returning in

1980 with his last two movies, Tom Horn and The Hunter, nei-

ther of which were major hits.

McQueen died of a heart attack after a long fight against

terminal cancer employing what many in the traditional

medical community considered to be unorthodox methods.

Menjou, Adolphe (1890–1963) A dapper leading

man during the silent era who went on to be one of Holly-

wood’s most polished character actors in 76 sound films.

Known for his black waxed mustache and sartorial splen-

dor—his reputation as one of Hollywood’s best-dressed men

sometimes overshadowed his reputation as an actor—Men-

jou became the quintessential “other man” in celluloid love

triangles. He excelled at playing the rich, sophisticated,

somewhat decadent older gentleman who threatens the

romantic bliss of hero and heroine.

Of French extraction, Menjou was born in Pittsburgh and

grew up to become an engineer, a profession he found little

time for when he stumbled upon his acting career. He

MENJOU, ADOLPHE

276

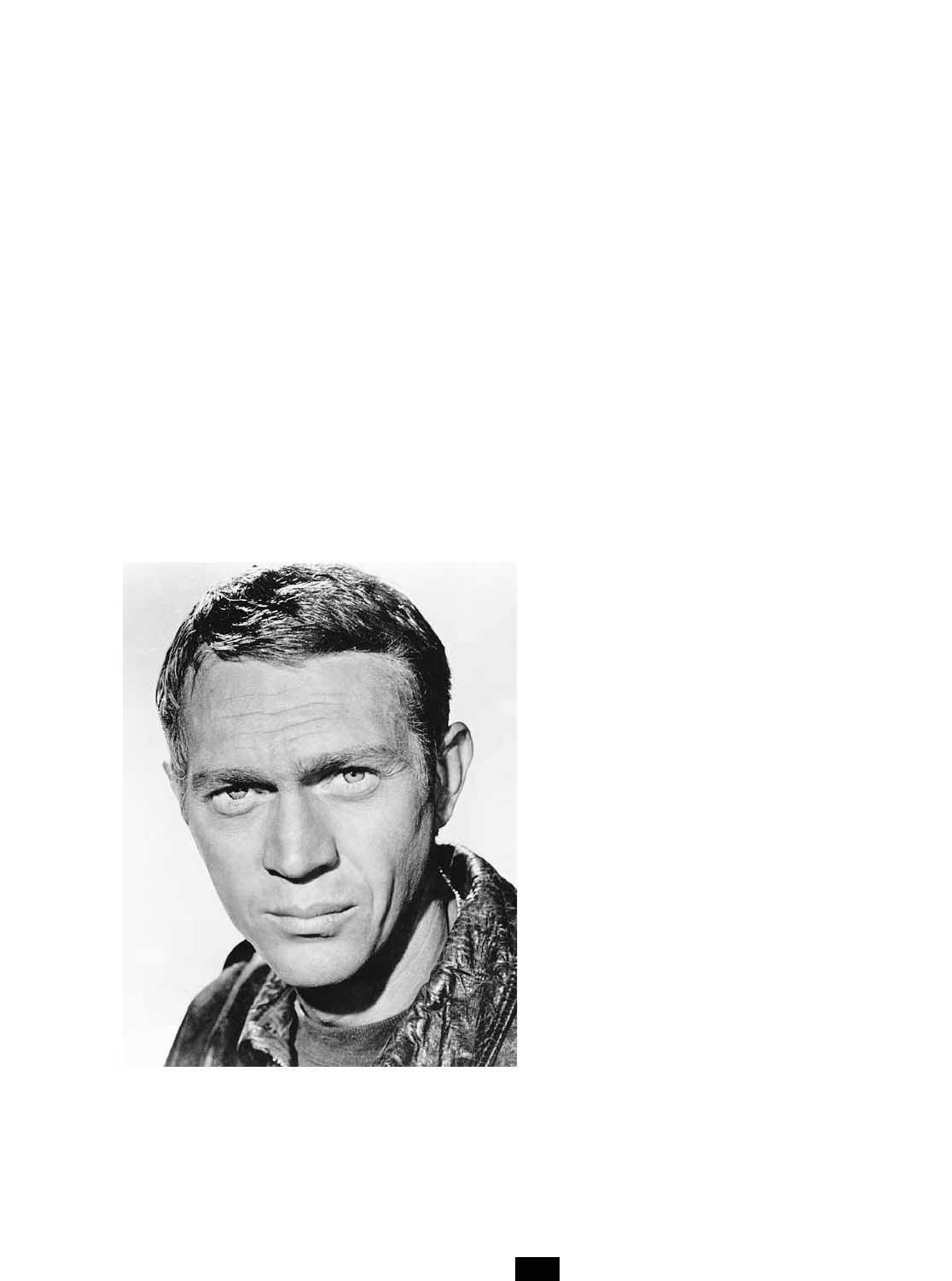

What Steve McQueen lacked in acting ability, he more

than made up in charisma. Playing vulnerable loners and

tough guys, he won audience sympathy. With his piercing

stare and weathered good looks, he also won the

admiration of men and the adoration of women.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF MOVIE STAR NEWS)

appeared in one film in 1916, The Blue Envelope Mystery, and

several others in 1917 before heading off to war in Europe.

When he returned, he pursued his acting career in the theater,

acquiring the poise that would later mark his acting style.

Menjou returned to Hollywood in 1921 and was immedi-

ately cast in significant roles in such major films as The Three

Musketeers (1921) and The Sheik (1921). The film that

brought him stardom, however, was

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

’s A

Woman of Paris (1923). The movie was a serious drama that

Chaplin wrote and directed as a vehicle for Edna Purviance,

his longtime leading lady. Menjou shined in the film as a

suave, sophisticated boulevardier, a role he never fully aban-

doned, playing variations on it throughout much of the rest

of his career.

Despite having a wonderful speaking voice, Menjou

could not quite hold onto his star status after the advent of

sound in the late 1920s. Nonetheless, he gracefully made the

transition to being an excellent supporting player in Morocco

(1930), in which he tempts

MARLENE DIETRICH

with his

wealth and power to forget her love for

GARY COOPER

.

Despite his continued success, largely as a major charac-

ter actor, Menjou did have several important leading roles in

the 1930s, the most memorable of which came in The Front

Page (1931), for which he won a Best Actor nomination. But

even in a leading role, he usually supported a more popular

star, such as

KATHARINE HEPBURN

in Morning Glory (1933),

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

in Little Miss Marker (1934), and

DEANNA

DURBIN

in One Hundred Men and a Girl (1937).

Though he was usually cast against major talent, Menjou

was not above stealing a few scenes when he had the chance,

as he did in Roxie Hart (1942), playing a wildly dramatic

lawyer defending

GINGER ROGERS

. Among his other fine

performances during the 1940s and 1950s were those in State

of the Union (1948), The Sniper (1952), and

STANLEY

KUBRICK

’s classic antiwar film Paths of Glory (1957), in which

he had his last great role, as an imperious French officer in

World War I. His final film was Pollyanna (1960), once more

in support of a child actress, this time Hayley Mills.

Meredith, Burgess (1912–1997) In a career span-

ning approximately 50 years, he proved himself a tireless

actor, director, writer, and producer in virtually every area of

popular entertainment.

Meredith had any number of colorful jobs in his youth,

among them reporter, vacuum-cleaner salesman, tie clerk at

Macy’s, Wall Street runner, and seaman. By 1930, however,

he began to work steadily in the theater, gaining glowing

reviews and the award for Best Performance of the Year by

the New York Drama Critics for his work in Little Ol’ Boy

(1933) and She Loves Me Not (1933). A small, elfin man, he

commanded attention, thanks in large part to his distinctive

speaking voice. It was his 1936 starring role on Broadway in

Winterset, that brought him to the attention of Hollywood.

He recreated his role of Mio for the film version of the play

in 1936.

A good deal of film work followed, most notably in major

supporting parts in movies such as Idiot’s Delight (1939), Sec-

ond Chorus (1941), That Uncertain Feeling (1941), and Tom,

Dick and Harry (1941). On the rare occasions when he had

true starring roles, Meredith was riveting. He gave what

many consider to be his most memorable performance as

Lenny in Of Mice and Men (1939), but he also earned raves

for his portrayal of Ernie Pyle in The Story of G.I. Joe (1945).

Meredith wrote, coproduced, and costarred with his wife,

Paulette Goddard, in the Jean Renoir-directed version of

Diary of a Chambermaid (1945), which remains one of his

most admired works. In 1947, Meredith directed (for the first

and last time) and starred in Man on the Eiffel Tower.

During the 1950s, Meredith was little seen in the movies.

He directed plays, starred in the theater, and gave his talents

to television until finally he made an impressive comeback on

the big screen in Advise and Consent (1962). He later appeared

regularly in films, making noteworthy contributions in mod-

est roles in such films as The Cardinal (1963), Madame X

MEREDITH, BURGESS

277

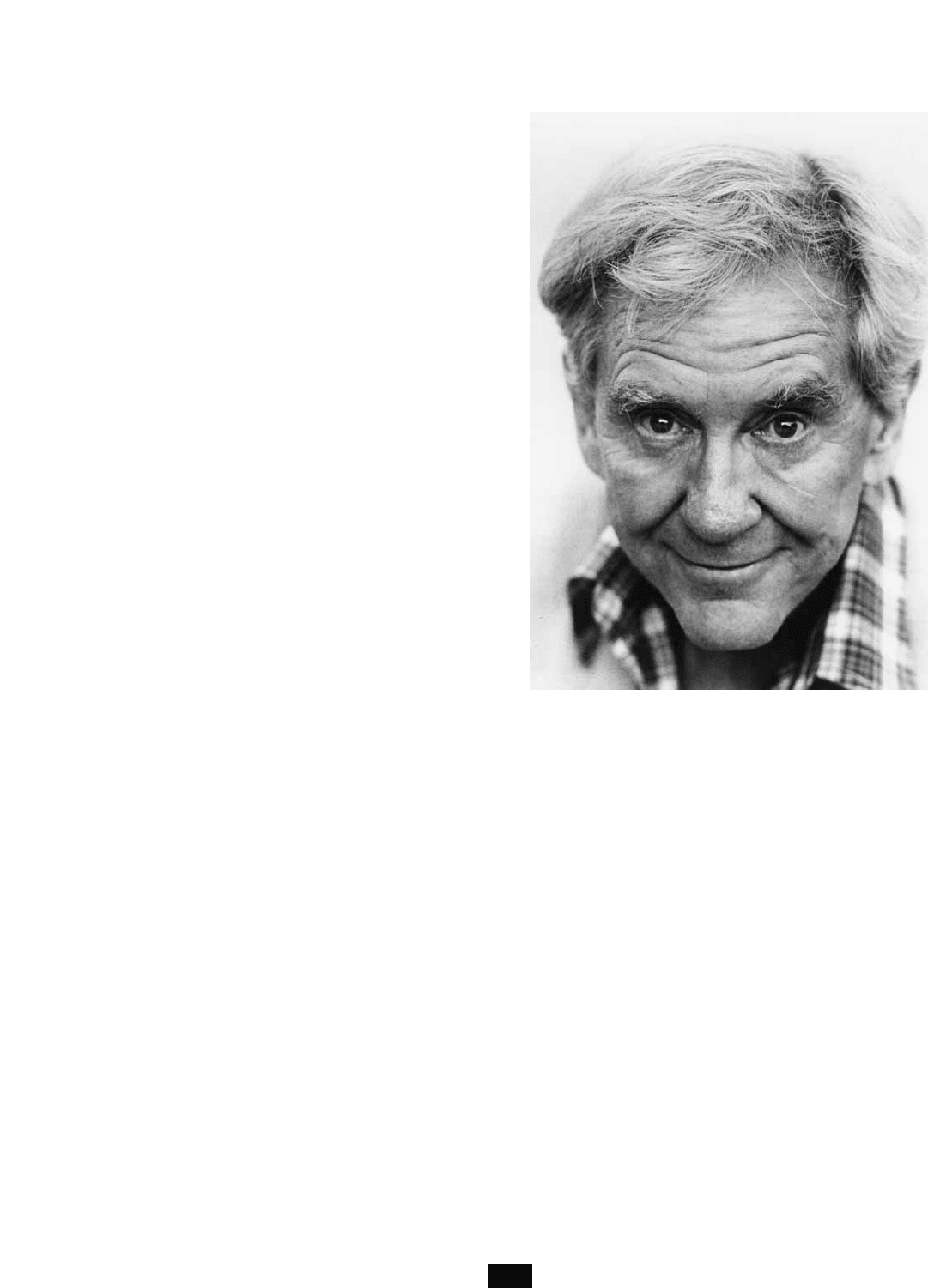

Burgess Meredith’s impish smile graced dozens of films in

a long and extremely varied career. Despite his starring

role in many classic films he was probably best known for

his performances as Sylvester Stallone’s manager in the

first three Rocky movies.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF

BURGESS MEREDITH)