Siegel S., Siegel B. The Encyclopedia Of Hollywood

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

(1965), A Big Hand for the Little Lady (1965), The Reivers

(1969), Day of the Locust (1973), Foul Play (1977), Clash of the

Titans (1979), and Full Moon in Blue Water (1988).

Though his face might be best remembered from his

strong and memorable performances in the first three Rocky

films, Meredith’s voice is still better known due to his work

in countless commercials.

message movies See

KRAMER

,

STANLEY

.

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) One of Holly-

wood’s Big Five film companies and, arguably, the most pres-

tigious. The complex history of its formation began with the

establishment in 1912 of a chain of theaters by former nick-

elodeon and peepshow entrepreneur Marcus Loew. Needing

more movie product, Loew acquired in 1920 the Metro Pic-

ture Corporation (which had been formed in 1915). Four

years later, the buildup continued with the acquisition of the

Goldwyn Pictures Corporation (formed in 1917) and Louis

B. Mayer Pictures (formed in 1918). The new organization,

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, was placed under the control of

LOUIS B

.

MAYER

as studio vice president and

IRVING THAL

-

BERG

as vice president in charge of production. The first

release under this new banner was He Who Gets Slapped

(1924), starring

LON CHANEY

and

NORMA SHEARER

. With

the sound revolution in the late 1920s, MGM’s first all-talk-

ing release was a musical, Broadway Melody (1929).

The years up to Thalberg’s death in 1936 are generally

considered MGM’s peak period. Popular and prestigious pic-

tures of the time included Greed (1924), The Big Parade

(1925), Ben-Hur (1927), Flesh and the Devil (1928), Freaks

(1932), Grand Hotel (1932), The Thin Man (1934), David Cop-

perfield (1935), Mutiny on the Bounty (1936), and The Good

Earth (1936). By the mid-1930s, MGM had 4,000 employees

and 23 sound stages on its 117-acre lot in Culver City. Some

40 features were made each year, costing approximately

$500,000 each. By the 1940s MGM’s boast that it presented

“more stars than there are in the heavens” seemed justified.

Luminaries included

GRETA GARBO

,

CLARK GABLE

, the Bar-

rymores,

JEAN HARLOW

,

JOAN CRAWFORD

,

SPENCER TRACY

,

MICKEY ROONEY

,

ELIZABETH TAYLOR

,

JUDY GARLAND

, and

WILLIAM POWELL

. Popular series included short subjects

such as the Pete Smith Specialties, the Tom and Jerry car-

toons, and the Hal Roach comedies; and such features as the

Andy Hardy, Tarzan, and Dr. Kildare movies. MGM also

released the pictures of its British production arm, Denham

Studios (under Michael Balcon), including The Citadel (1938)

and Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939); as well as numerous inde-

pendently made movies, most notably Gone With the Wind

(1939). A particularly noteworthy series of musicals appeared

in the 1940s and early 1950s under the guidance of produc-

ers and filmmakers

ARTHUR FREED

, Stanley Donen, Vin-

cente Minnelli, and Gene Kelly: Meet Me in St. Louis (1944),

The Pirate (1948), On the Town (1949), An American in Paris

(1952), Singin’ in the Rain (1953), and Seven Brides for Seven

Brothers (1955).

After 1951, many changes affected the studio. The sepa-

ration of MGM from its Loew’s parent company was forced

by federal antitrust action. Following a bitter dispute

between Mayer and Loew’s president Nicholas Schenck,

Mayer was forced to resign and was replaced by his former

production chief,

DORE SCHARY

. In 1957, a substantial pack-

age of theatrical features was sold to television. More corpo-

rate turnovers ensued. In 1969, Kirk Kerkorian bought the

studio and began to sell off the assets, disposing of the

British studios and companies such as MGM Records. A

public auction sold off many of the costumes and props. In

1979, MGM merged with United Artists (which henceforth

distributed its product) to form MGM/UA Entertainment

Company; the amalgamation produced only sporadic the-

atrical releases, including the successful Spaceballs (1987) and

Moonstruck (1988). In 1985, Kerkorian sold the MGM film

library, studio, and film lab to Atlanta entrepreneur Ted

Turner for more than $1.5 billion. After a lengthy series of

financial setbacks, MGM, a mere shadow of its former self,

finally resettled in sunny Santa Monica, where it occupies a

modern office complex called MGM Plaza. Although the

site covers 1 million square feet, the new home seems

insignificant when compared with its original kingdom in

Culver City.

MGM is no longer a real studio in the classic sense of

the word. It has no back lot, sound stages, or production

facilities. When MGM wants to make a movie, it rents

space at another studio. What MGM does, though, is con-

tinue to come up with financing and produce 10 to 12

movies a year (less than half of what most other studios

grind out), and it owns certain bankable franchises, such as

the James Bond series.

During the 1980s, financial problems diminished MGM’s

role in the industry as a major studio production entity. The

company even preferred to focus on its hotel interests in Las

Vegas. The MGM Grand Hotel includes a Wizard of Oz

amusement park. The studio had a three-year period without

a single success until in 1994 Stargate broke the spell.

In 1995, the studio had its ups and downs. That year,

MGM’s efforts included such bombs as Showgirls and Hack-

ers, but 1995 also gave the studio a series of major hits such

as

JOHN TRAVOLTA

’s Get Shorty, the science-fiction horror

film Species, the critically acclaimed Leaving Las Vegas, and the

007 thriller Goldeneye. In 1996, MGM releases included The

Birdcage, Mulholland Falls, Kingpin, and Marshal Law. The

following year, 1997, was a dry one, but in 1998 MGM

released the 007 hit Tomorrow Never Dies. Yet MGM had not

shown a profit since 1988. In 1996, the studio lost the shock-

ing amount of $744 million. MGM was saved once again by

James Bond, its most reliable property. In 1999, the studio

released another 007 adventure, The World Is Not Enough,

starring Pierce Brosnan, which once again proved to be a big

hit, as well as another Brosnan thriller, The Thomas Crown

Affair. Further signs of MGM recovery were Stigmata (2000),

Hannibal (2001), Legally Blonde (2001), and Bandits (2001).

Midler, Bette See

SINGER

-

ACTORS

.

MESSAGE MOVIES

278

Milestone, Lewis (1895–1980) A director of more

than three dozen movies spanning the silent era to the 1960s.

Yet for all of his many and varied projects, only a handful of

his films have survived the test of time. One of these is All

Quiet on the Western Front (1930), Hollywood’s most power-

ful antiwar film.

Milestone had his first exposure to filmmaking during

World War I when he served in the signal corps. After his

discharge, he headed for Hollywood, where he continued his

education as an editor. In 1925 he directed his first film, Seven

Sinners. The script was written by

DARRYL F

.

ZANUCK

.

In 1927, Milestone won an

ACADEMY AWARD

as Best

Director for the

HOWARD HUGHES

produced Two Arabian

Knights. Five films later, he won his second Best Director

Academy Award for All Quiet on the Western Front (1930).

Though not a genius of the stature of

ORSON WELLES

,

Milestone suffered a fate similar to the great director’s. Every

project he completed after All Quiet on the Western Front was

compared unfavorably to his earlier effort.

But Milestone still had some triumphs during the 1930s

and 1940s, though they were relatively few. He directed the

original film version of The Front Page (1931) with dash. In

1939 Milestone turned John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice and

Men into a hit movie, though most of Hollywood was sure

that audiences would stay away in droves. The director also

made several more noteworthy films, among them The

Strange Love of Martha Ivers (1946) and another Steinbeck

project, The Red Pony (1948).

A Walk in the Sun, which Milestone directed in 1946,

brought him a new measure of respect and success. It was a

thoughtful, introspective film about a soldier’s experience in

battle. The movie was the first to introduce the idea of a bal-

lad weaving in and out of the storyline. The much-copied

device would find its way into films such as High Noon (1952)

and reach its apotheosis in Cat Ballou (1965).

Milestone’s career plummeted in the 1950s with such

minor works as Melba (1953), They Who Dare (1954), and

Pork Chop Hill (1959). After directing the rat-pack vehicle

Ocean’s Eleven (1961), he bowed out with a gargantuan flop,

Mutiny on the Bounty (1962).

If not for All Quiet on the Western Front and a few other

films, Milestone would have been long forgotten. But the

power of this director at his best has sustained his reputation.

See also

ANTIWAR FILMS

.

Milius, John (1945– ) A highly underrated writer-

director whose right-wing politics and macho themes have

made him a pariah to the more-liberal critical establishment.

His beliefs aside, Milius is a gifted screenwriter and a

dynamic and often inspired director.

Born to a well-to-do shoe manufacturer, Milius spent

most of his youth in Southern California, where he was

known to spend his days surfing. Later, studying film at USC,

he met and befriended future Star Wars director George

Lucas and future screenwriters Walter Huyck and Gloria

Katz. After leaving college, Milius got a job at American

International Pictures, for whom he later cowrote his first

screenplay, The Devil’s 8 (1969). He went on to collaborate on

the script of Evel Knievel (1971) before receiving serious

recognition as the coscreenwriter of the

ROBERT REDFORD

hit Jeremiah Johnson (1972). He also provided the story and

screenplay for

JOHN HUSTON

’s The Life and Times of Judge

Roy Bean (1972). Milius has previously worked on the script

for

CLINT EASTWOOD

’s Dirty Harry (1971), receiving no

screen credit, but he later provided the story for the sequel,

Magnum Force (1972), cowriting the film’s screenplay.

Milius was a hot commodity in Hollywood in the early

1970s. He parlayed his screenwriting success into a chance to

direct his own screenplay of Dillinger (1973). Made on a small

budget, it was a fast-paced, intelligent, and quirky film that

caught the attention of the critics. He followed that modest

success with a huge leap forward, making the sweeping, nos-

talgic adventure film The Wind and the Lion (1975).

Milius was hailed as a brilliant new director—until he

wrote and directed his third film, Big Wednesday (1978), a

movie loosely based on his own life as a young surfer. The

critics called it a wipeout, and it sank almost instantly

beneath the critical waves. Yet the film was a breathtaking

masterpiece about friendship and the tides of time.

Big Wednesday didn’t destroy Milius’s film career, but it

did send him briefly in different directions. He produced and

collaborated on the original story for

STEVEN SPIELBERG

’s

1941 (1979). Milius was also executive producer of

PAUL

SCHRADER

’s Hardcore (1979) and later producer of the sleeper

hit of 1983, Uncommon Valor. In the meantime, he had

returned to screenwriting, coscripting Francis Coppola’s bril-

liant Apocalypse Now (1979).

Milius didn’t reenter the directorial ranks until 1981

when he wrote and directed Conan the Barbarian with

ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER

in the title role. It was the film

that turned Schwarzenegger into a credible box-office attrac-

tion, and despite mixed-to-poor reviews from the critics, it

was a sizable commercial success.

If the critics were not wild about Conan, they absolutely

detested Red Dawn (1984), a movie that dramatized the resist-

ance of teenage Americans to a Russian/Cuban invasion.

Again, despite poor press, the film did moderately well at the

box office.

After a long hiatus from directing, Milius made a bold, if

commercially unsuccessful, return to the screen with Farewell

to the King (1989). He directed Flight of the Intruder (1991)

before turning to made-for-television movies. He continued

screenwriting, contributing screenplays for Geronimo: An

American Legend (1993) and Clear and Present Danger (1994).

Milland, Ray (1905–1986) An actor who appeared in

films for more than 40 years, his greatest success being in the

1940s in contemporary roles. Handsome and suave, but with

a tough edge, and possessed of a mild and pleasing Welsh

accent, Milland was good at light comedy and even better in

hard-boiled roles. Unfortunately, the actor rarely had good

material to work with, and of his more than 120 movies (in

more than 90 of them he was a leading man), a mere dozen,

at best, are distinguished films.

MILLAND, RAY

279

Born Reginald Truscott-Jones in Neath, Wales, Milland

first used his stepfather’s surname, Mullane, as his show-busi-

ness moniker. After a tour of duty as a Royal Guardsman, and

thanks to the intercession of an actress friend, he made his

acting debut, under the name Spike Milland, in the English

film The Plaything (1929). Having a screen credit led to more

work in England but no spectacular successes.

ANITA LOOS

spotted the actor and put in a good word for him at MGM.

At first, Hollywood was not thrilled to have him. His first

American film appearance was in The Bachelor Father (1931),

and he was offered only smallish roles in seven subsequent

films before heading back to England, an apparent flop.

Work in two English films followed, but Milland had begun

to get a good public response for his work in some American

movies, so he returned to Hollywood.

He was given small parts again in films such as Bolero

(1934) and We’re Not Dressing (1934) but soon graduated to

featured roles in films such as Next Time We Love (1936) and

Wings Over Honolulu (1937). In 1940 he had a breakthrough

with a starring role in French Without Tears. Showing a gen-

uine flair for comedy, he was finally established as a box-

office draw. A number of light comedies followed, such as

Irene (1940), The Doctor Takes a Wife (1940), and The Major

and the Minor (1942), which confirmed and solidified his star

status. Yet, except for the last of these films, none of his vehi-

cles was particularly memorable.

Things finally began to change in 1944 when Milland

began to star in movies with a more cynical point of view such

as The Uninvited (1944),

FRITZ LANG

’s Ministry of Fear (1944),

and the movie for which he is most well known, Lost Weekend

(1945), in which he gave his Oscar-winning tour de force as an

alcoholic. Despite his Oscar and newfound respect as an actor,

Milland rarely received good scripts. His good films during

the rest of the 1940s were far and few between, the best being

The Big Clock (1948) and Alias Nick Beal (1949).

His record was even more uneven in the 1950s but had

notable peaks in the western Bugles in the Afternoon (1952),

The Thief (1952), and Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder (1954),

in which he played

GRACE KELLY

’s murderous husband. In

the second half of the decade, Milland tried his hand at

directing as well as acting in the off-beat western A Man

Alone (1956); his efforts were well received. Milland’s best

films of the late 1950s and early 1960s were often the ones in

which he directed himself, among them The Safe-Cracker

(1958) and Panic in Year Zero! (1962).

Milland had a successful turn on TV with his own series,

Markham, and made several good cheapie horror films in the

early 1960s, such as Premature Burial (1961) and X—The Man

With the X-Ray Eyes (1963). His career faltered during the

rest of the 1960s, however, until it was resurrected by a

strong character part in Love Story (1970).

Throughout the 1970s Milland made some truly ghoulish

(and foolish) horror movies. Some did rather well at the box

office and were respectable efforts, while others were excruci-

atingly bad. Milland’s more interesting work in the genre was

in Frogs (1972) and The Man with Two Heads (1972). Later, he

had small roles in classier (though not much better) films such

as The Last Tycoon (1976) and Oliver’s Story (1978).

When his health began to decline, Milland finally

stopped working. He died, having amassed a truly eclectic

body of work.

Miller, Arthur C. (1895–1970) Noted for his exqui-

site composition, he was an accomplished cinematographer

who photographed more than 130 feature films between

1915 and 1951. His early fame rested on having shot The Per-

ils of Pauline (1914), the original blockbuster serial. But in a

long and distinguished career, he had many triumphs, the

most memorable achieved during his tenure at

TWENTIETH

CENTURY

–

FOX

in the 1940s.

Miller grew up fascinated by cameras, but his introduc-

tion to the motion picture business was purely accidental. As

related in an interview with Leonard Maltin in his book,

Behind the Camera, Miller explained that when he was 13

years old, “I went to work for a horse dealer, delivering

horses . . . One day I saw this crowd gathered outside a Ger-

man beer garden, and I sat there astride this horse bareback.

A guy came over and asked me if I wanted to work in moving

pictures. I said, ‘Doing what?’ He said, ‘You can ride a horse

bareback, can’t you?’” Miller was hired as an extra, but found

a greater interest in the technical side of the business. In that

same year, 1908, he got a job in a film laboratory. Though he

was still a teenager, he soon began to work as a cameraman

on shorts for

EDWIN S

.

PORTER

and others.

At Bay (1915) was the first feature film he photographed,

beginning a long, nearly exclusive, collaboration with director

George Fitzmaurice that lasted through 36 films, until 1925.

His films of the later 1920s and early 1930s were relatively

minor, but he came into his own when he began to work at

Fox in 1932. His importance to the studio is evidenced by the

fact that he was assigned to photograph

SHIRLEY TEMPLE

,

Fox’s most important asset. He was the cinematographer of

several of the moppet’s hits, such as Bright Eyes (1934), The

Little Colonel (1935), Wee Willie Winkie (1937), Heidi (1937),

and Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (1938).

In the 1940s, Miller won three Oscars for How Green Was

My Valley (1941), The Song of Bernadette (1943), and Anna and

the King of Siam (1946). Examples of other Miller-pho-

tographed films during his golden era are The Mark of Zorro

(1940), Tobacco Road (1941), Man Hunt (1941), Gentlemen’s

Agreement (1947), and The Gunfighter (1950).

On doctor’s orders, Miller retired from cinematography

in 1951 after shooting The Prowler. He remained active, how-

ever, working in various capacities for the American Society

of Cinematographers until his death in 1970.

Minnelli, Vincente (1910–1986) MGM’s preeminent

director of musicals during the 1940s and 1950s, his ability to

integrate musical numbers naturally into the framework of

his films began a trend that continues to this day. Conversely,

Minnelli also pioneered the sublime artificiality of the musi-

cal genre.

As is often the case with directors of musicals, Minnelli’s

early training was in the theater. He had become a respected

MILLER, ARTHUR C.

280

designer and later a director of Broadway shows before

MGM’s premier producer of musicals,

ARTHUR FREED

, per-

suaded Minnelli to give Hollywood a try.

Among his earliest work at MGM was the direction of

individual musical sequences in other directors’ films. (For

instance, he often directed Lena Horne’s musical numbers.)

Minnelli’s first solo directorial credit was the all-black film

Cabin in the Sky (1943). The movie was well received by white

audiences, and Minnelli was on his way to a long and suc-

cessful career.

He directed Ziegfeld Follies (1945), a variety film that pre-

sented a long roster of great stars, including

FRED ASTAIRE

and

JUDY GARLAND

. Minnelli later married Garland and

fathered their daughter, Liza.

His first real breakthrough as a director came with Meet

Me in St. Louis (1944), in which Minnelli told a nostalgic

family story with warmth and feeling, weaving the musical

numbers in and out of the film with a grace and style that

seemed effortless.

With films such as The Pirate (1948), An American in Paris

(1951), The Band Wagon (1953), and his Academy Award–win-

ning direction for Gigi (1958), Minnelli put his stamp on

movie musicals, filming them almost exclusively in the studio

in bright, lively colors. Many of his films were criticized for

being unnaturally stylized, but this was a deliberate technique

used to emphasize the dreamlike quality of the musical.

Not all of Minnelli’s musicals were classics, but even his

lesser efforts stand out, such as Yolanda and the Thief (1945),

Brigadoon (1954), and Bells Are Ringing (1960).

Because Minnelli is known primarily as a director of

musicals, it is often forgotten that roughly two-thirds of his

nearly three dozen films are comedies and dramas. Some of

the best among them are the taut thriller Undercurrent

(1946), the charming comedy Father of the Bride (1950), the

great biopic of van Gogh Lust for Life (1956), and the gritty

Southern drama Home from the Hill (1960).

Minnelli worked with the top people in the musical

field—Arthur Freed, Fred Astaire,

GENE KELLY

, and Judy

Garland among them. In his dramas, his most memorable

work was with

KIRK DOUGLAS

, who starred in four of Min-

nelli’s movies, including his wonderfully acerbic attack on

Hollywood, The Bad and the Beautiful (1952).

Minnelli’s powers as a director seemed to fade rather

abruptly after the early 1960s. He ended his career with A

Matter of Time (1976), a poorly received film made primarily

as a family affair, starring his daughter Liza. Unfortunately,

none of his later films had the panache of his earlier efforts.

But the quality of the vast majority of his work is undeniable.

Vincente Minnelli’s name remains synonymous with the

great MGM musicals.

Miranda, Carmen (1909–1953) The “Brazilian Bomb-

shell” whose memorable comic caricature of South American

sensuality made her a hit virtually from the beginning of her

relatively short Hollywood career.

Born Maria da Carmo Miranda da Cunha in Portugal,

she moved with her family to Brazil while still a youngster. By

her mid-20s, she was a popular radio and film star well

beyond her country’s borders. She was imported to America

in 1939, singing “South American Way” in the Broadway

show Streets of Paris. The number was a show stopper, and

she was asked to reprise it in a

BETTY GRABLE

movie musi-

cal, Down Argentine Way (1940).

Miranda stole the movie from Grable, and American

audiences went crazy over this outrageous singer with wild

costumes, fruit-basket hats, thousand-watt smile, and garish

makeup. Despite a seemingly ridiculous appearance (or

because of it), she won legions of fans.

While Miranda was never the heroine of a romance (Hol-

lywood was still too closed-minded for that), she often played

the friend of the love interest, giving her advice in fractured

English and in song, and even though her acting ability was

woefully inadequate, the sheer force of her personality was

enough to sustain her career as a leading lady for the better

part of a decade.

Her most memorable movies are That Night in Rio (1941)

and The Gang’s All Here (1943). The latter film was directed

by

BUSBY BERKELEY

; though it is a rather poor movie, it is

without a doubt the ultimate in kitsch, and it was appreciated

even then for its good-natured silliness.

Miranda’s movies were rarely any good though they were

never boring. The singer was much too bizarre a presence

ever to be dull. Musicals such as Greenwich Village (1944) and

Something for the Boys (1945) kept her before the public, but

her novel appeal suffered the inevitable decline. Nonetheless,

she was an amusing and offbeat costar to Groucho Marx in

Copacabana (1947).

In all, Miranda graced just 14 films in the United States.

In her last comedy, Scared Stiff (1953), she had a featured

role. She died that same year of peritonitis, closing a colorful

if brief chapter in Hollywood musical history.

Mitchell, Thomas See

CHARACTER ACTORS

.

Mitchum, Robert (1917–1997) A laconic, sleepy-

eyed actor who survived a long string of villainous roles in

low-budget westerns and an equally long stint playing psy-

chopaths, as well as a controversial drug bust early in his

career, finally emerged a star and male sex symbol. Yet even

as a star, Mitchum received little respect from critics until

more recent years, when he was finally seen as one of the few

remaining screen giants (along with

KIRK DOUGLAS

and

BURT LANCASTER

) of Hollywood’s golden studio era. With

his sardonic manner, bedroom eyes, and a deep, commanding

drawl, Mitchum epitomized the new breed of rebellious

movie tough guy.

Mitchum lost his father when he was two years old and

was raised by his mother and stepfather. His older sister was

the first to enter show business, working as a nightclub enter-

tainer when she was a teenager. Mitchum came around to the

acting profession much later. After a rough adolescence in

New York’s Hell’s Kitchen, the young man took a wide

assortment of jobs from ditch digger to factory worker. After

MITCHUM, ROBERT

281

trying his hand as a professional boxer, Mitchum joined a

local theater group at the urging of his sister. His wandering

days had finally come to an end.

In addition to acting, Mitchum also began to write every-

thing from children’s plays to song lyrics. He even penned a

piece about Jewish refugees fleeing Hitler’s Germany that

ORSON WELLES

used in a 1939 benefit at the Hollywood

Bowl. During the late 1930s, however, Mitchum made his

living working as a flack for the famous astrologer of the day,

Carroll Richter.

Later, after his 1940 marriage, he took a job as a sheet-

metal worker in Burbank, California. To keep his sanity (he

hated the job), he spent several evenings a week acting for a lit-

tle community theater. Unhappy with his life, his mother sug-

gested he take a stab at the movies. Mitchum thought he might

manage to find some work as an extra and gave it a whirl.

From the start, Mitchum was more than an extra. His first

film was Border Patrol (1943), a Hopalong Cassidy western in

which he played a bad guy. Mitchum would go on to appear in

six more “Hoppy” movies and a whopping total of 23 films

during his first year and a half as a movie actor, most of them

either westerns or war movies. Among the more well-known

films in which he had small parts were The Human Comedy

(1943), Gung-Ho! (1943), and Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944).

Mitchum began to receive leading roles in low-budget

horse operas such as Nevada (1944) and West of the Pecos

(1945), but his biggest break came when he was given a major

supporting role in the “A” movie The Story of G.I. Joe (1945).

His work in that film earned him a Best Supporting Actor

Oscar nomination.

The postwar years were perfect for Mitchum’s gritty style

of acting. He came into his own in hard-edged movies such

as Crossfire (1947), Pursued (1947), and Out of the Past (1947).

Toward the latter half of the 1940s, he was fast evolving from

leading man to major star—until he was arrested for posses-

sion of marijuana in 1948. Ultimately he spent 50 days in jail

after being found guilty.

Surprisingly, this didn’t hurt the actor’s career. Viewed as

a rebel, Mitchum became an even bigger star in films such as

The Big Steal (1949) and The Racket (1951).

The 1950s were full of extreme highs and lows for

Mitchum. Although he tended to walk through a large num-

ber of poor movies, his work with strong directors was quite

impressive. His best movies during that era were Nicholas

Ray’s The Lusty Men (1952),

OTTO PREMINGER

’s River of No

Return (1954), the

CHARLES LAUGHTON

–directed The Night

of the Hunter (1955),

JOHN HUSTON

’s Heaven Knows Mr. Alli-

son (1957), and Arthur Ripley’s Thunder Road (1958).

The 1960s started well for Mitchum with his strong per-

formances in Home from the Hill (1960) and The Sundowners

(1960). He also began to take chances with his career, playing

a sinister and chilling villain to

GREGORY PECK

’s hero in Cape

Fear (1962), taking on comedy in The Last Time I Saw Archie

(1961), and starring in the movie adaptation of the play Tw o

for the Seesaw (1962). Though he worked steadily throughout

the rest of the decade, after big-budget films such as The

Longest Day (1962), his vehicles became more and more for-

gettable, and he often found himself playing in secondary

roles to actors such as

JOHN WAYNE

in El Dorado (1967),

DEAN MARTIN

in Five Card Stud (1968), and Yul Brynner in

Villa Riders! (1968).

Mitchum made a comeback playing against type in David

Lean’s lush romance, Ryan’s Daughter (1970). Critics finally

took notice of the actor’s ability and the movie scored well at

the box office. Thanks to his success in Ryan’s Daughter,

Mitchum found a whole new audience, and he slowly devel-

oped an art-house following, starring in such films as the

highly regarded The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), Farewell,

My Lovely (1975), and The Big Sleep (1978), based on two

Raymond Chandler Philip Marlowe detective novels.

Despite his success in these films, the aging actor was

offered few other substantive roles, and his career began to

wane until he hit it big once again in such 1980s TV mini-

series as North and South and The Winds of War.

Though rarely seen on the big screen during the 1980s,

he was impressive in That Championship Season (1982) and Mr.

North (1988). He stepped in at the last moment to take the

late John Huston’s part in the latter movie, winning high

praise for his work.

After appearing in the 12-episode made-for-television

series War and Remembrance (1988–89), Mitchum was not as

fortunate in his roles. He appeared in The Brotherhood of the

Rose (1989), Woman of Desire (1993), a soft-porn flick made by

John and Bo Derek, Backfire (1994), a terrorism spoof about

exploding toilets, and Dead Man (1995), a

JOHNNY DEPP

vehicle, in which he had a small part.

MARTIN SCORSESE

smartly cast Mitchum as Lieutenant Elgart in his 1991

remake of Cape Fear, which featured

ROBERT DE NIRO

in the

earlier Mitchum role of Max Cady.

Mix, Tom (1880–1940) The most popular of all the

silent cowboy stars, he rode supreme on the celluloid range

in the late 1910s and throughout most of the 1920s. Unlike

the gritty westerns of

WILLIAM S

.

HART

, which preceded his,

Mix’s horse operas were patently unrealistic. Thanks to mag-

nificent location shooting, excellent cinematography, tight

direction by many of Hollywood’s better directors (he rarely

directed himself during his most popular period), and big-

budget production values, Mix’s films became the westerns by

which other oaters were judged.

Born in Mix Run, Pennsylvania, young Tom led an

adventurous life long before becoming a movie star. Though

his studio biography made him appear to be a combination of

Colonel Frémont and Wild Bill Hickock, Mix was actually a

sergeant in the U.S. Army (although he deserted in 1902) and

was a member of the Texas Rangers in 1906. Yet it was his

rodeo fame that served him best when he found his way into

the movies, appearing in a

WILLIAM N

.

SELIG

production,

Ranch Life in the Great South West (1910). In addition to per-

forming several stunts, he supplied the horses from his own

ranch for the film.

Selig was impressed with Mix, and he was hired to con-

tinue working as a combination wrangler, stuntman, and

actor. Before long, however, Mix was starring in and direct-

ing his own one- and two-reel light western comedies with

MIX, TOM

282

modest success. In fact, he made more than 100 films for

Selig before he finally left the company for Fox, where he

(and his famous horse, Tony) catapulted to stardom in 1917

in action-oriented features such as The Daredevil (1920), Just

Tony (1922), and The Rainbow Trail (1925).

Mix made more than 60 features at Fox, becoming that

studio’s biggest draw. But his star faded with the coming of

sound. He made a few silent westerns for FBO (Film Book-

ing Offices of America) in 1928 and 1929 and then retired

from the screen to tour with Ringling Bros. Circus. With the

rise of the “B” western in the early 1930s, though, Mix was

lured back to Hollywood, where he made a handful of low-

budget films between 1932 and 1934, the most well-known

among them an early version of Destry Rides Again (1932).

Mix died in an automobile accident in 1940.

See also

WESTERNS

.

Mohr, Hal (1894–1974) A cinematographer who pio-

neered the use of dollys, booms, and other innovations in a

long and varied film career. He shot well more than 100 fea-

ture films, the vast majority of them during the sound era. In

fact, Mohr has the distinction of being the cinematographer

of the very first sound film,

THE JAZZ SINGER

(1927).

MOHR, HAL

283

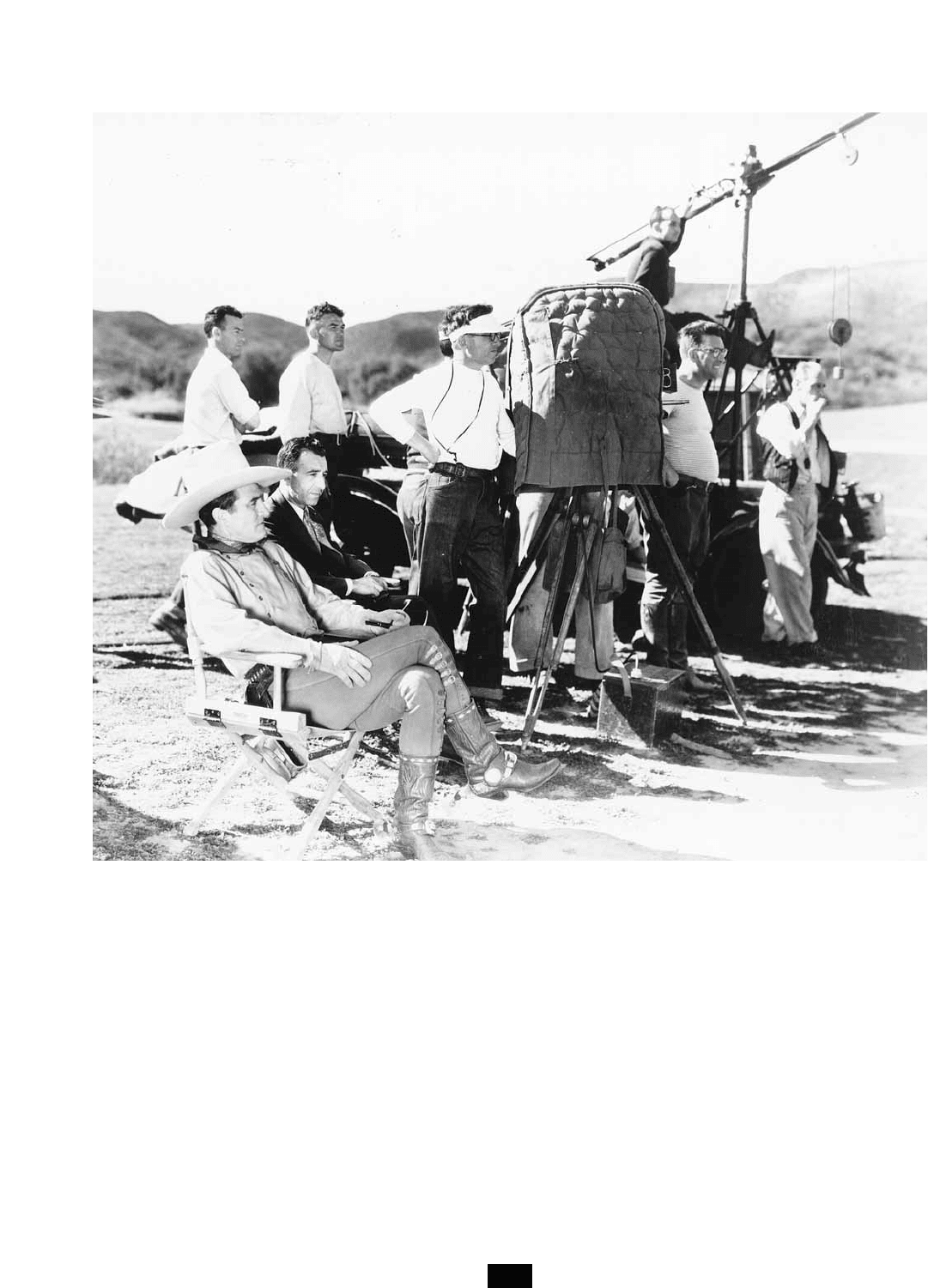

Tom Mix, seen here in the foreground wearing the white cowboy hat, was among the most popular of all the silent-screen

cowboys. Mix’s escapist entertainments provided the simple format that was used in thousands of future Hollywood westerns.

(PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIEGEL COLLECTION)

The son of a well-to-do San Francisco family, Mohr built

his own camera as a young man and began to make primitive

newsreels that he sold to the nickelodeons sprouting all over

the bay area. At one point, he was actually put out of business

by the infamous Patents Company, which confiscated his

camera. Mohr continued making films, however, eventually

making his way down to Hollywood, where he codirected

two

HAROLD LLOYD

comedies before heading off to battle in

World War I.

After returning to Hollywood, Mohr decided to concen-

trate on becoming a cinematographer. He had previously

held every function imaginable, including director, producer,

writer, and actor, and as he related to Leonard Maltin in his

interview book, Behind the Camera, Mohr felt that the most

creative job in the industry was that of the cameraman.

Mohr began to photograph feature films in the early

1920s, shooting such movies as Little Annie Rooney (1925),

Sparrows (1926), and Old San Francisco (1927). His startling

visual effects on early sound films are evident in Broadway

(1929), the impressive Technicolor movie The King of Jazz

(1930), and the elegant fantasy Outward Bound (1930).

Mohr jumped from studio to studio, working on a wide

variety of films from program fillers such as Charlie Chan’s

Courage (1934) at Fox to “A” movies such as Destry Rides

Again (1939) at Universal. At Fox, he photographed leading

lady Evelyn Venable in David Harum (1934) and then

promptly married her.

Though he worked at most of the studios, Mohr did his

most memorable work of the 1930s at

WARNER BROS

. For A

Midsummer Night’s Dream (1935), he won the first of his two

Oscars. Curiously, he hadn’t been nominated that year for an

Academy Award but won in a write-in vote, the only Oscar

winner ever to receive the statuette in that fashion. After he

won, the academy did away with the right of members to vote

for anyone but the official nominees. Among his other fine

Warner Bros. movies during that decade were Captain Blood

(1935) and Bullets or Ballots (1936). Mohr tried his hand at

directing in 1937, making When Love Is Young. The experi-

ence wasn’t a fully satisfying one and he went back to cine-

matography.

In the 1940s, Mohr brought a cool, crisp honesty to the

sober anti-Nazi film Watch on the Rhine (1943) and a delicious

eeriness to The Phantom of the Opera (1943), for which he won

his second and last Oscar. In the latter 1940s, however, he

worked steadily but the films he shot were less important.

Mohr turned the tide in the 1950s with Fritz Lang’s off-

beat western Rancho Notorious (1952). Among his starkly shot

and powerful films during the next decade were The Wild One

(1954), Baby Face Nelson (1957), and Underworld U.S.A. (1961).

The aging cinematographer slowed down in the 1960s, but

he demonstrated his skill one last time as the photographic

consultant on

ALFRED HITCHCOCK

’s Topaz (1969), a movie

more noteworthy today for its visual effects than its plot.

Monroe, Marilyn (1926–1962) She was Hollywood’s

legendary sex goddess, the voluptuous blonde bombshell

with an outrageously sexy walk and little-girl innocence and

vulnerability. Her film career was relatively short—less than

15 years—and her major starring roles numbered only 11,

but her impact was enormous. After she became a star, every

studio in Hollywood tried to come up with their own bosomy

blonde version of Monroe. Among the actresses molded in

her image were

KIM NOVAK

, Jayne Mansfield, and Mamie

Van Doren. Monroe was never nominated for an Oscar, nor

did she receive any other major acting award—in fact, only a

handful of her films are worthy of note—yet, four decades

after her death, she remains among Hollywood’s most endur-

ing and compelling screen personalities.

Born Norma Jeane Mortenson to the then unmarried

Gladys Mortensen, a film cutter and movie fanatic who pos-

sibly named her daughter after her favorite movie star,

Norma Talmadge, Monroe was raised mostly by foster par-

ents. Due to a history of mental illness, Mrs. Mortensen

spent a large part of her adult life in sanitariums.

Norma Jean’s adolescent years were full of loneliness and

trauma. According to her one-time maid and confidante,

Lena Pepitone, Monroe was raped by one of her foster par-

ents. Finally, at the age of 16, in an effort to escape to a bet-

ter life, she married 21-year-old Jim Dougherty. Not long

after they were wed, Dougherty joined the merchant marine.

The couple was divorced four years later.

Meanwhile, to help the war effort and to earn extra

money, Monroe began to work in a defense-industry plant,

packing parachutes. David Conover, an army photographer,

arrived at the factory to take pictures of women working in

support of the boys overseas. His shots of Marilyn for Yank

magazine brought her a great deal of attention, leading to a

career as a model. It was her modeling agency that decided to

change Monroe’s hair color from its natural brown to blonde.

Long interested in the movies due to her mother’s

involvement in the film industry, Monroe began to audition

at several studios. The actress’s first break came when Ben

Lyon, the casting director of Twentieth Century–Fox, signed

her to a contract. Lyon gave her the name Marilyn, taking if

from Marilyn Miller, an actress whom he knew who had died

in 1936 at the age of 37, a victim of poisoning. The actress

took her mother’s maiden name for her surname because she

liked the way it sounded with Marilyn.

Monroe was given acting lessons at Fox and was eventu-

ally cast in tiny roles in two movies, Scudda Hoo! Scudda Hay!

(1948), in which she can be seen in a canoe for a short

moment, and The Dangerous Years (1948). Seeing no potential

in the actress, Fox promptly dropped her option. As it hap-

pened, however, Marilyn had been keeping company with

69-year-old

JOSEPH M

.

SCHENCK

, a powerful producer at

Fox with connections all over Hollywood. Schenck, as a favor

to Marilyn, called the president of

COLUMBIA PICTURES

,

HARRY COHN

, and asked him to give her a contract. Cohn

signed her up, gave her the lead in a “B” movie musical,

Ladies of the Chorus (1949), and then dropped her from the

company. According to Monroe, Cohn let her go because she

rebuffed his sexual advances.

With no steady work and trying to make a living, Mon-

roe posed nude for a calendar spread, earning $50 for her

efforts. When she became famous and the photos resurfaced,

MONROE, MARILYN

284

the calendar sold more than 1 million copies. The publicity

actually helped her career rather than hurt it.

In the immediate aftermath of her lost opportunity at

Columbia, Marilyn freelanced, hoping to catch on some-

where. She had a small role in the last Marx Brothers movie,

Love Happy (1949), and got the attention of William Morris

agent Johnny Hyde. He went on to become both her lover

and her mentor, guiding her career and getting her small but

important parts in such films as The Asphalt Jungle (1950) and

All About Eve (1950).

Monroe was starting to get press attention, and Hyde suc-

ceeded in garnering for her a seven-year contract at

TWENTI

-

ETH CENTURY

–

FOX

just before he died of a heart attack in

1951. The studio groomed her for stardom, giving her mod-

est roles in films such as As Young As You Feel (1951), Love Nest

(1951), Let’s Make It Legal (1951), Clash by Night (1951), We’re

Not Married (1952), and Monkey Business (1952). In most of

these early films, she was cast as a dumb blonde, the studio

banking on her sex appeal rather than her acting abilities.

Finally, Monroe had her first major role in Niagara (1953),

and despite the film’s mediocrity, her presence in the movie

turned it into a hit. The actress’s career suddenly blossomed.

Her follow-up film, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), teamed

her with another busty movie star,

JANE RUSSELL

, and the hit

musical proved that Marilyn could do more than look beauti-

ful. She could sing in her own inimitable breathy, sexy style,

and she could dance with provocative bravado. But the real

surprise was that she was a surprisingly adept comedienne.

Monroe continued her successful role as an improbably

innocent gold digger in How to Marry a Millionaire (1953).

She continued to play a variation on the dumb blonde in

There’s No Business Like Show Business (1954) and The Seven

Year Itch (1955). She played a somewhat wiser dramatic char-

acter in the mediocre River of No Return (1954). Although all

of her films were big hits, Monroe was unhappy at not being

given an opportunity to play a wider variety of roles.

Attempting to save her integrity as an actress, she walked out

on her contract and went to New York to study acting with

Paula and Lee Strasberg.

Monroe made headlines for her personal life as well as for

her fight with Twentieth Century–Fox. After her nine-month

marriage to former baseball hero Joe DiMaggio, she met and

fell in love with America’s leading playwright, Arthur Miller,

who became her third and last husband.

Meanwhile, Fox finally capitulated and gave Marilyn a

new contract with the right to approve scripts and directors.

Her next film under that contract was the hit Bus Stop (1956),

proving that Marilyn knew what she was doing. For the first

time, critics who had previously scoffed at her acting ability

began to change their tune.

Unfortunately, her next film was the rather weak The

Prince and the Showgirl (1957) with

LAURENCE OLIVIER

. She

bounced back strongly with

BILLY WILDER

’s hugely success-

ful Some Like It Hot (1959). Let’s Make Love (1960) was not as

successful a film, but it attained a certain notoriety because of

Monroe’s affair with costar Yves Montand.

By this time, though, Marilyn’s inconsistent professional

behavior was becoming more and more a topic of discussion

in the movie industry. She was often late to arrive on the set

and sometimes didn’t show up at all. Monroe was considered

extremely difficult to direct; a number of her directors pub-

licly complained about both her tardiness and the constant

need to retake her scenes because she could not give a con-

sistently credible performance.

Well aware of her reputation,

JOHN HUSTON

agreed to

direct Monroe in a film that Arthur Miller had written for

her: The Misfits (1961). Because of delays caused by her emo-

tional problems and dependence on sleeping pills, the film

went way over budget. Nonetheless, the star delivered a pow-

erful and elegant performance as an ethereal child/woman.

Though generally well received by the critics, The Misfits was

not a winner at the box office (at least not on its initial

release). A week before the movie opened, she announced her

divorce from Miller.

Monroe began to make Something’s Got to Give (1962),

but the film was never finished. After two box-office failures,

her unprofessional behavior became intolerable. When the

film fell hopelessly behind schedule, she was fired.

Through her acquaintance with

FRANK SINATRA

and

Peter Lawford, the actress had met and had become inti-

mately involved with President John F. Kennedy as well as his

brother Robert, the attorney general. Monroe grew increas-

ingly ill, depending heavily on sleeping pills. She died of a

drug overdose under mysterious circumstances, with some

reputable journalists claiming that Robert Kennedy was in

some fashion involved in her death.

See also

SEX SYMBOLS

:

FEMALE

.

monster movies In a narrow definition that excludes sis-

ter genres of horror and science fiction, these are the movies

that present huge and terrifying creatures that are not other-

wise humanoid, supernatural, or extraterrestrial. Monster

movies, more so than any other films, depend on special

effects. Horror can be expressed through makeup, lighting,

and camera angles, and science fiction comes alive on film due

in large part to costumes, props, and sets (although special

effects have played a large role since

STAR WARS

in 1977).

Monster movies, however, depend almost entirely upon visual

tricks to work. Monsters must be created and then made to

seem awesome, real, and as fierce-looking as possible.

In 1925, the first major monster movie was made, The

Lost World, with startling special effects work by Willis

O’Brien. The film shocked audiences with massive creatures

of another age, forever establishing dinosaurs as the standard

monster of the genre.

In 1933, a new monster emerged to do battle with both

man and dinosaur, King Kong. Again, the genius behind the

special effects was Willis O’Brien. King Kong, a beauty-and-

the-beast story featuring a surprisingly sympathetic giant

gorilla, remains to this day, the most realistic, expressive, and

intelligent monster movie ever made. Unfortunately, it

spawned a mediocre sequel, Son of Kong (1933), and a very

weak cousin, Mighty Joe Young (1949). It should be noted that

the Japanese, who created one of the most popular of all

monster dinosaur movies, Godzilla (1956), eventually pitted

MONSTER MOVIES

285

“their” creature against “ours” in King Kong vs. Godzilla

(1963). Not so surprisingly, in the Japanese version, Godzilla

wins; in the American release print, King Kong is the victor.

The dinosaur has thrived in monster movies throughout

the decades, making its appearance in films such as the Vic-

tor Mature vehicle One Million B.C. (1940) and its 1966

remake, One Million Years B.C., starring Raquel Welch, with

dinosaurs brought to life by Willis O’Brien disciple Ray Har-

ryhausen. Dinosaurs have also reared their massive heads in

movies such as an unlikely combination of western and mon-

ster movie called The Beast of Hollow Mountain (1956), as well

as Dinosaurus (1960) and The Valley of Gwangi (1969).

The height of monster-movie popularity was the 1950s,

an era dominated by fear of the atomic bomb. Monster

movies played on that fear with plots suggesting that nuclear

testing might awaken sleeping giants from their rest, as in

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), or that radiation from

atomic tests might create giant mutant life forms that would

destroy civilization. In Them (1954) the monsters were giant

ants, in It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955) a giant octopus

threatened humankind, and in The Beginning of the End

(1957) the world lived in fear of massive marauding

grasshoppers.

Monster movies have become virtually extinct, helped

along in their demise by the colossal flop remake of King

Kong (1976). Audiences tend not to be so amazed or fright-

ened by giant creatures on the screen anymore; perhaps

we’ve become too sophisticated for such make-believe. Rid-

ley Scott’s Alien (1979) and

JOHN CARPENTER

’s The Thing

(1982) delivered horrifying alien monsters that proved that

monster movies could still frighten audiences, but it wasn’t

until

STEVEN SPIELBERG

used cutting-edge computer tech-

nology to bring dinosaurs to life in Jurassic Park (1993) that

the monster movie made a true comeback.

The blockbuster success of Jurassic Park led to two

sequels, The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997) and Jurassic Park

III (2001). With the magic of computer-generated images

(CGI) proven, giant monsters returned in full force in movies

such as Godzilla (1998), a deeply flawed American remake of

the Japanese classic, Evolution (2000), and Eight-Legged Freaks

(2002). Not to be outdone, though, such movies as Tremors

(1990), Tremors 2: Aftershocks (1996), Tremors 3: Back to Per-

fection (2001), and Jeepers Creepers (2001) proved that tradi-

tional special effects and minimal CGI could still be effective

in bringing scary monsters to the screen.

Another popular monster franchise returned to the

screen in a big way with The Mummy (1999), a Raiders of the

Lost Ark–style adventure that told the tale of an ancient

Egyptian priest who returns from the dead. A blockbuster

sequel followed, The Mummy Returns (2001), as well as a spin-

off of a popular character into a solo movie, The Scorpion King

(2002). Series writer-director Stephen Sommers had previ-

ously directed the low-profile but creepy monster flick Deep

Rising (1998).

montage Generally, the art of editing together the scenes

of a movie. Montage has also come to mean the layering of a

great many images in rapid succession, often dissolving one

on top of the other. Montage of that sort is usually meant to

convey the passing of time, such as pages falling off a calen-

dar, or of places visited all in one wild night, which might

include a series of shots of neon-lit nightclub signs dissolving

into one another.

Hollywood’s acknowledged master of montage was

Slavko Vorkapich, who created some truly incredible mon-

tages within the films of other directors. One must see his

montage—a surrealistic opening sequence—in Crime With-

out Passion (1934) to appreciate the colossal visual impact that

a few mere moments of film can create.

Montgomery, Robert (1904–1981) A debonair lead-

ing man at MGM during the 1930s, known then more for his

glamorous costars than for his own cinematic personality. But

that changed in the late 1930s and 1940s when Montgomery

stopped playing in light comedies and became a tough guy.

Looking back on his career today, it seems that his best work

was as an actor-director of a handful of films in the mid- to

late 1940s. In any event, Montgomery had a fascinating and

multifaceted career.

He was born Henry Montgomery, and his one ambition

was to be a writer. However, he found self-expression as an

actor in the 1920s, playing in a repertory company in

Rochester, New York. He made his way to Broadway in the

late 1920s and was whisked away to Hollywood to appear in

So This Is College? (1929).

Soon thereafter, the handsome and self-effacing actor was

the leading man and foil for MGM’s greatest female stars. He

made six movies with

JOAN CRAWFORD

, five with

NORMA

SHEARER

, and supported

GRETA GARBO

, Tallulah Bankhead,

CONSTANCE BENNETT

,

MYRNA LOY

, and

ROSALIND RUSSELL

.

He might have gone on in that fashion had he not been

active in Hollywood politics, helping to organize the Screen

Actors Guild. MGM was none too pleased with his union

activities and sought to ruin his image (and by extension, his

career) by casting him as an especially loathsome villain in

Night Must Fall (1937). The result, however, was a hit movie

MONTAGE

286

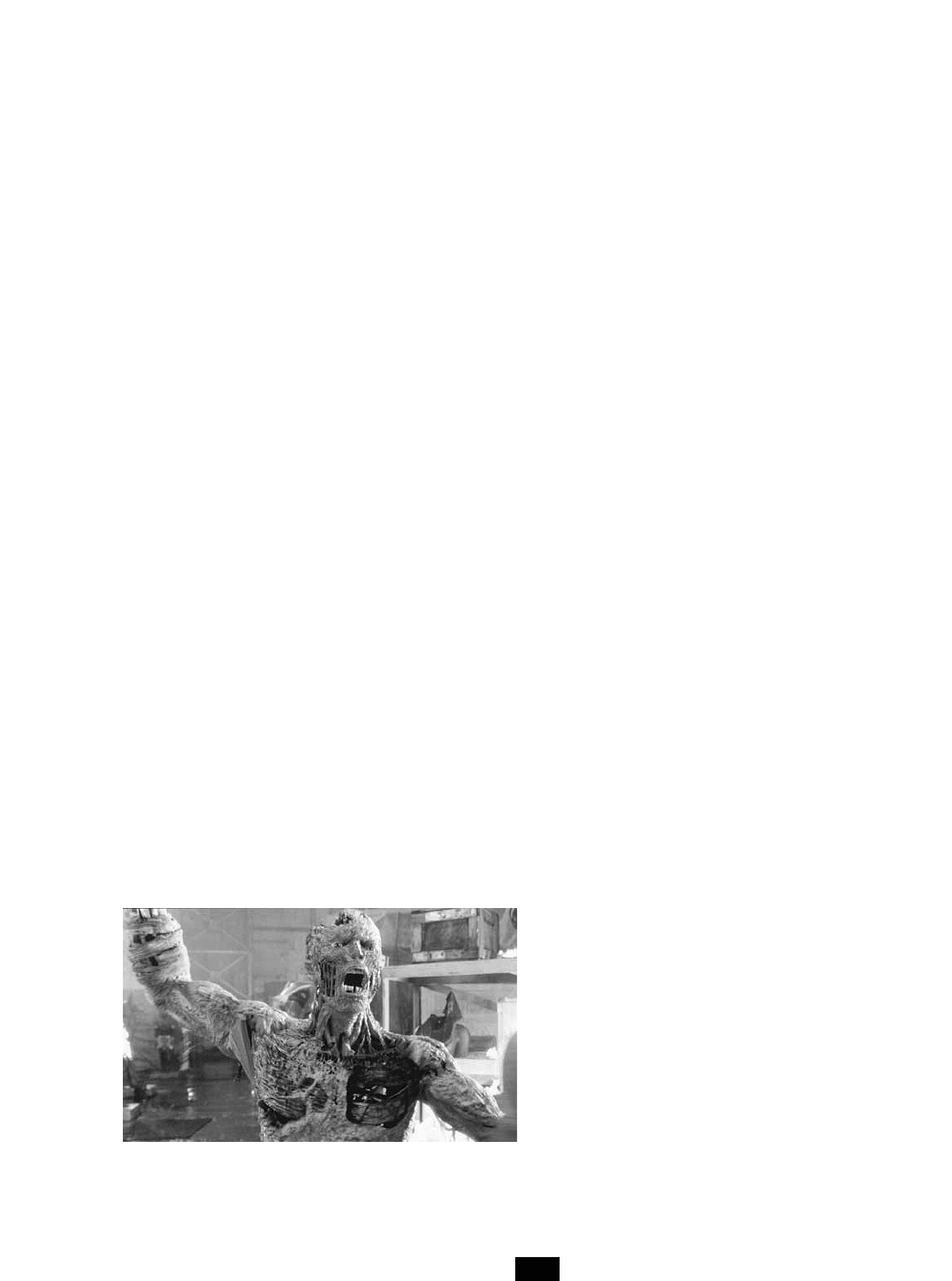

The Mummy Returns (2001) (PHOTO COURTESY

UNIVERSAL STUDIOS)

and a greater level of critical and audience respect for Mont-

gomery as an actor.

MGM didn’t want anything to do with their star if they

could help it, and they proceeded to loan him out to other

studios whenever they could. Still, both at MGM and else-

where, Montgomery turned in a number of fine perform-

ances in films such as Yellow Jack (1938), The Earl of Chicago

(1940), and Here Comes Mr. Jordan (1941), which was later

remade as Heaven Can Wait (1978) with

WARREN BEATTY

in

Montgomery’s role.

After finishing his World War II military service as a lieu-

tenant commander in the U.S. Navy, he made a triumphant

comeback in

JOHN FORD

’s They Were Expendable (1945). He

then starred and directed for the first time in a movie that still

sparks comment today, The Lady in the Lake (1946). In that

film, he played Raymond Chandler’s famous detective, Philip

Marlowe. Montgomery made the entire movie using a subjec-

tive camera technique: The entire film was shot as if the cam-

era were Marlowe, with the audience seeing everything

through his eyes. Montgomery/Marlowe was seen only when

the character looked into a mirror or into a clear pool of water.

Clearly, the one-time struggling writer had found a new

avenue of self-expression as a director, and he continued to

direct and star with flair, making Ride the Pink Horse (1947), a

moody, atmospheric gangster film that ranks as a classic of late

1940s

FILM NOIR

. The movie’s unfortunate failure at the box

office kept him working in front of the cameras for other

directors, but he returned to his dual profession in 1949, with

two lesser films, Once More My Darling and Your Witness.

Montgomery then walked away from the movie business,

finding more freedom to act and direct material of his own

choosing in television. He returned only once more to the big

screen to direct Jimmy Cagney in The Gallant Hours (1960).

See also

SUBJECTIVE CAMERA

.

Moore, Dickie See

CHILD ACTORS

.

Moore, Dudley (1935–2002) The diminutive Eng-

lish actor surprisingly became a Hollywood star when he

was well into his forties. But long before he emerged as a

comic and romantic movie personality, Moore lent his con-

siderable talents to the movies as a comedian, composer,

screenwriter, and singer. Very much a cult favorite during

the second half of the 1960s and through most of the 1970s,

his stardom came suddenly in 1979 in

BLAKE EDWARDS

’s hit

film 10, which was soon followed by his bravura perform-

ance in the smash success Arthur (1981). Unfortunately, his

film career after those two blockbusters was considerably

less successful.

Music was Moore’s early preoccupation. He learned to

play the violin at an early age, but his later mastery of the

organ earned him a scholarship to Oxford’s Magdalen Col-

lege. There he received a B.A. in music in 1957 and a degree

in composition in 1958.

Moore’s first big show-business break came in the univer-

sity revue that he helped write and in which he also per-

formed called Beyond the Fringe. It was so successful that it

played on the London stage and was brought to Broadway,

where he was introduced to the American audience.

During the 1960s, he and Peter Cook teamed up to

become a popular, if cerebral, comedy team. The two

appeared in The Wrong Box (1966). It was Moore’s first film

and was quickly followed by Bedazzled (1967), in which he and

Cook starred. In addition, Moore cowrote the story, com-

posed the film’s musical score, and also sang. The hip comedy

became a cult classic and it still holds up very well today.

Bedazzled may have been the most enjoyable of Moore’s

early films. Others of note include 30 Is a Dangerous Age,

Cynthia (1968), for which he also cowrote the script and pro-

vided the score, The Bed Sitting Room (1969), Those Daring

Young Men in Their Jaunty Jalopies (1969), and Alice’s Adven-

tures in Wonderland (1972).

After spending a large part of the 1970s on the stage,

Moore charmed movie audiences with his supporting per-

formance in the hit

GOLDIE HAWN

and

CHEVY CHASE

film

comedy Foul Play (1978). The film 10 (1979) turned him into

a major romantic-comedy star, earning him the nickname

“Cuddly Dudley.” After the flop Wholly Moses (1980), Moore

scored again in Arthur (1981), playing a drunken millionaire

with great charm and considerable humor. A flurry of films

followed, each of them trying to capitalize on Moore’s cute-

ness. But Six Weeks (1982), Romantic Comedy (1983), Lovesick

(1983), and Unfaithfully Yours (1984) were, at best, mediocre.

For the most part, Moore was consistently better than his

material, charming his way through films that he might have

been wiser to avoid.

1984 saw a resurgence in Moore’s box-office clout when

he starred in Micki & Maude (1984), a clever, frenetic comedy.

Unfortunately, he starred in the stinker Best Defense that same

year and followed it with his (literally) elfin performance in

the poorly received Santa Claus, The Movie (1985). After dis-

appearing from movie screens for two years, he starred in

Like Father, Like Son (1987), yet another box-office loser, but,

as always, he garnered sympathetic notices from critics.

Finally, in an effort to recoup his popularity, Moore

agreed to star in Arthur 2, On The Rocks (1988). The film

received mixed reviews and an equally mixed response at the

ticket window. His last two feature films, Crazy People (1990)

and Blame It on the Bellboy (1992), were undistinguished, and

after making two films for television, he announced in 1999

that he had progressive supranuclear palsy, a disease that

eventually deprived him of his speech and made him immo-

bile. When he received the Commander of the British

Empire award from Queen Elizabeth in November 2001, he

was unable to speak and sat in a wheelchair. He died of pneu-

monia, a complication of his disease, in 2002.

Moore, Julianne (1960– ) A rising star in the late

1990s, Julianne Moore graduated from Boston University in

1983. Seven years later, she was building a modest following

with genre films such as The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992)

and The Fugitive (1993) but also working with such prestigious

directors as

ROBERT ALTMAN

in Short Cuts (1993) and Cookie’s

MOORE, JULIANNE

287