Sha W., Malinov S. Titanium Alloys: Modelling of Microstructure, Properties and Applications

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Titanium alloys: modelling of microstructure148

Following the above reasoning and fitting the resistivity data to the JMA

equation assuming different n values for β to α + β transformation for

temperatures above and below 900 °C, the derived kinetics parameters as

well as the different mechanisms of the α phase nucleation and growth for

both alloys are summarised in Table 6.6.

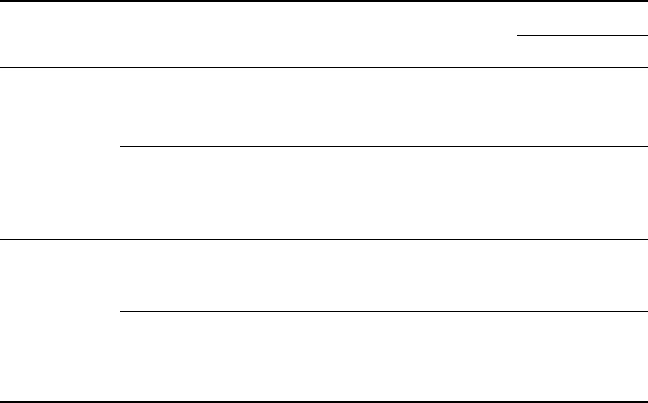

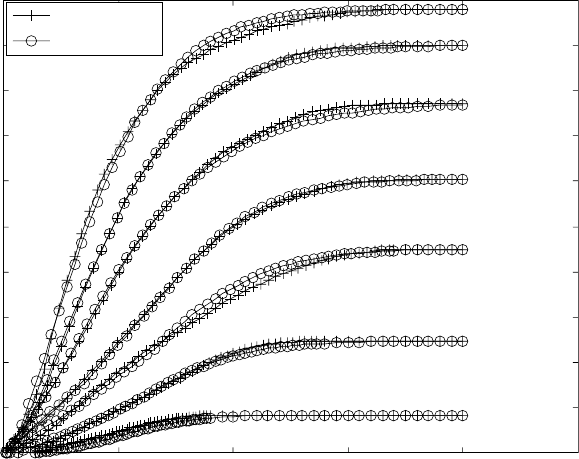

In Fig. 6.14, the calculated (from the JMA theory) and the experimental

(from the resistivity measurements) transformation kinetics are compared

for different constant temperatures. Calculated fractions are based on Eq.

[6.2], using the n and k values given in Table 6.6. A very good agreement

between the calculated and the experimental curves is evident. This agreement

supports the validity of the obtained JMA kinetic parameters, which can be

used in the heat treatment practice of the titanium alloys to trace and predict

the course of β to α + β transformation under different isothermal conditions.

The approach described above using two different mechanisms and,

respectively, two different n values of the β to α + β transformation is

different from the approach used in Chapter 7: in that chapter the kinetics of

the same transformation are modelled during continuous cooling based on

differential scanning calorimetry data. A single n value for the entire temperature

interval of the transformation is attributed to continuous cooling conditions.

In the following, some explanation of the different approaches is given.

The mechanisms of the transformations are different for continuous cooling

and isothermal conditions with respect to the nucleation and growth conditions.

This difference is significant for phase transformations taking place on cooling

Table 6.6

Johnson–Mehl–Avrami kinetic parameters for two different mechanisms

of the β to α + β transformations in Ti 6-4 and Ti 6-2-4-2 alloys at various

temperatures of isothermal transformations

Alloy

T

(°C) α phase morphology JMA parameters

nk

Ti-6Al-4V 950 Grain boundary α phase, and some 1.1 0.045

920 amounts of α plates nucleated and 0.055

900 grown from the grain boundaries 0.068

870 Mixed: Homogeneously nucleated 1.35 0.025

850 and plate-like grown α structure, 0.024

800 and grain boundaries nucleated and 0.025

750 grown α phase (Fig. 6.4c) 0.033

Ti-6Al-2Sn- 930 Grain boundary α phase, and some 1.15 0.035

4Zr-2Mo- 900 amounts of α plates nucleated and 0.043

0.08Si grown from the grain boundaries

850 Mixed: Homogeneously nucleated 1.48 0.013

800 and plate-like grown α structure, 0.017

750 and grain boundaries nucleated 0.018

735 and grown α phase (Fig. 6.4f) 0.044

The Johnson–Mehl–Avrami method 149

Ti-6Al-4V

Experimental

Calculated

0 10203040506070

Time (sec)

(a)

Amount of α phase (vol. %)

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

750 °C

800 °C

850 °C

870 °C

900 °C

920 °C

950 °C

Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si

0 10 20304050 607080

Time (sec)

(b)

Amount of α phase (vol. %)

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

735 °C

750 °C

800 °C

850 °C

900 °C

930 °C

6.14

Experimental and calculated kinetics of the β to α + β

transformation at different temperatures for (a) Ti-6Al-4V and

(b) Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si alloys.

Titanium alloys: modelling of microstructure150

in titanium alloys. In the case of continuous cooling, at each temperature, the

transformation starts and proceeds in conditions of microstructure that has

been formed at previous stage(s). For example, at 850 °C, the transformation

on continuous cooling is in conditions of nucleation sites that already exist

(grain boundary α formed on cooling from β-transition to the current

temperatures), which are preferable sites for further growth. In the case of

isothermal exposure, the sample is cooled rapidly from the β-field to the

temperature of isothermal exposure (e.g. 850 °C). At this temperature,

spontaneous nucleation (mainly homogeneous) and growth take place. In

other words, in the cases of isothermal exposure, when the undercooling is

high, the amount of the α phase formed and grown within the former

β grains will be higher as compared to the grain boundary α (see Fig. 6.4f

and g). These two different mechanisms result in a somewhat different

morphology of the α phase formed and imply a difference in the Avrami

index derived from continuous cooling and isothermal experiments.

Nevertheless, both approaches and models have their own importance and

area of application.

6.7.2 Ti 8-1-1

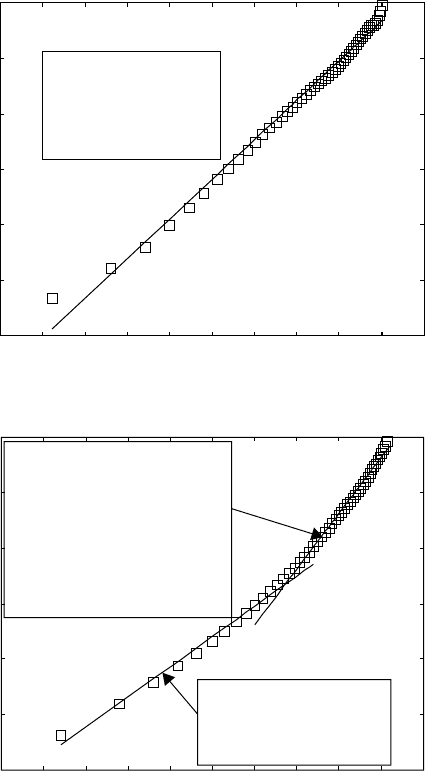

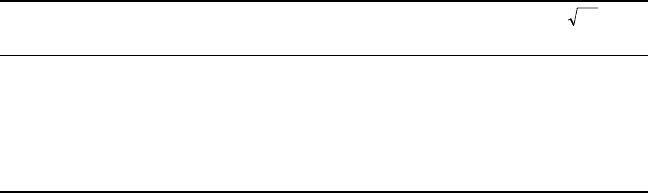

For lower temperatures (750, 800 and 850 °C), the experimental measurements

are described well by single straight lines (see Figs. 6.12 and 6.15). However,

at higher temperatures (900 °C and above), there is an obvious tendency for

change of the line slope (see Fig. 6.12d–f). The data apparently consist of

two parts which can be fitted with two separate lines (see Fig. 6.15b). This

observation implies that the mechanism of the transformation alters during

the course of the transformation.

The above data are in agreement with metallography of the alloy quenched

from different temperatures (see Section 6.3.3). There are different mechanisms

for the β to α + β phase transformation in Ti 8-1-1 alloy, depending on the

temperature of the isothermal transformation. At lower temperatures

(<900 °C), the main part transforms by homogeneous nucleation (within the

former β grains) and grows into plate-like or lamellar-like α phase. At higher

temperatures (≥900 °C), firstly, grain boundary α phase is formed.

Subsequently, the α phase fraction increases in conditions of decreasing

nucleation rate (exhausting of the grain boundaries of the former β phase).

Concurrently or subsequently, there is some amount (depending on the

temperature) of α plates nucleating and growing from the grain boundaries.

These different stages of the transformations correspond to the two separate

lines in Fig. 6.15b. The first stage takes place within the first 8–15 s, depending

on the temperature of isothermal transformation. Finally, it should be

remembered that the mechanism of the transformation alters gradually in the

time.

The Johnson–Mehl–Avrami method 151

Acceptable good fittings are possible for any n value ranging within 1.25–

1.5 and for all curves in Fig. 6.2c. Different mechanisms of the transformation

give different Avrami index (n values) for the kinetics of the β to α + β

transformation.

Considering all of the above, the experimental data in Fig. 6.2c can be

800 °C

n

= 1.42

Homogeneous

nucleations and

plate-like growth

In(In(1/(1–

y

)))

2

1

0

–1

–2

–3

–4

–1 –0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4

In(

t

)

(a)

900 °C

n

2

= 2.01

Grain boundary α phase

formation with decreasing

nucleation rate and

α plates nucleated and

grown from the grain

boundaries

In(In(1/(1–

y

)))

2

1

0

–1

–2

–3

–4

–1 –0.5 0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5 4

In(

t

)

(b)

n

1

= 1.09

Grain boundary

α phase formation

6.15

Plots of ln(ln(1/(1–

y

))) against ln(

t

) showing the different

mechanisms of the β to α + β transformation for Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V alloy

at different temperatures. (a) 800 °C; (b) 900 °C

Titanium alloys: modelling of microstructure152

fitted to the JMA equation, Eq. [6.2], by setting the n value free but constant

for the different mechanisms observed and discussed above. The derived

parameters, as well as the different mechanisms of the α phase nucleation

and growth, are summarised in Table 6.7. These are in agreement with the

general theory of phase transformations. At lower temperatures, an n value

of 1.42 is derived, corresponding to the transformation mechanism of

homogeneous nucleation and plate-like growth. Similar n values have been

derived for the β to α + β transformation at the same temperatures for Ti-

6Al-4V and Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si alloys (Section 6.7.1). The rate

constant k increases with decreasing temperature (see Table 6.7), implying

that the transformation is controlled by the rate of nucleation. Lower temperature

of the transformation corresponds to higher degree of undercooling, therefore

higher driving force of the transformation. Under these conditions, the rate

of nucleation (mainly homogeneous) controls the overall transformation rate.

The Ti-6Al-4V and the Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si alloys have similar

tendencies in the k values (Section 6.7.1).

At higher temperatures, as stated above, the mechanism of the transformation

alters during the course of the transformation. Firstly, grain boundary α

phase is formed. This corresponds to an n value of 1.01 (see Table 6.7). At

this stage, clear temperature dependence of the rate constant k is not apparent.

Subsequently, the mechanisms of the transformation smoothly alter to grain

boundary α phase formation in conditions of exhausting grain boundaries

and α-plates nucleated and grown from the grain boundaries, corresponding

to an n value of 1.96. The rate constant k at this stage increases with increasing

temperature (see Table 6.7). This implies that the overall transformation rate

at this stage is controlled by diffusion.

The change of the mechanism of the β to α + β transformation for the Ti-

8Al-1Mo-1V alloy at high temperatures is not observed in Section 6.7.1 for

Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si alloys. The reasons for this

difference are mainly the difference in the composition and the microstructure

of the alloys. The Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V alloy has a lower molybdenum equivalent

compared to the Ti-6Al-4V and the Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si alloys, so,

at the same temperature of isothermal exposure, a larger amount of the α

phase is in equilibrium and needs to be transformed. The transformation

continues until the equilibrium amount of α is reached, even if all grain

boundaries of the former β phase are exhausted. Moreover, the Ti-6Al-4V

and the Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-0.08Si alloys in general (Boyer et al., 1994),

and in these particular cases, have finer microstructure of both the low

temperature α and the high temperature β phases than the Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V

alloy, implying larger amount of phase boundaries. Finally, the difference in

the β-transus temperature (1000 °C for Ti-6Al-4V and Ti-6Al-2Sn-4Zr-2Mo-

0.08Si alloys and 1040 °C for Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V alloy) may also have an

influence on the change of the kinetics during the course of the transformation.

The Johnson–Mehl–Avrami method 153

Table 6.7

Johnson–Mehl–Avrami kinetic parameters and different mechanisms of the β to α + β transformation in Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V alloy at

various temperatures of isothermal transformations

T

(°C) First stage Second stage

Mechanism of transformation JMA parameters Mechanism of transformation JMA parameters

nk nk

975 Grain boundary α 1.01 0.043 Grain boundary α phase formation 1.96 0.0085

950 phase formation 0.043 in conditions of exhausting 0.0065

925 0.043 grain boundaries and α plates 0.0052

900 0.043 nucleated and grown from 0.0050

the grain boundaries

850 Homogeneously nucleated 1.42 0.029

800 and plate-like grown 0.035

750 α structure 0.044

Titanium alloys: modelling of microstructure154

In Section 6.7.1, there is also weak evidence for altering of the mechanism

of the transformation at high temperature.

It should be pointed out that the mechanisms of the β to α + β transformation

in Ti 8-1-1 alloy depend on the temperature but they do not change abruptly

with the temperature. The change is gradual (around 900 °C) from one

mechanism to another. So, the different mechanisms suggested (Table 6.7)

mean ‘the main mechanism of the transformation at the corresponding

temperature’.

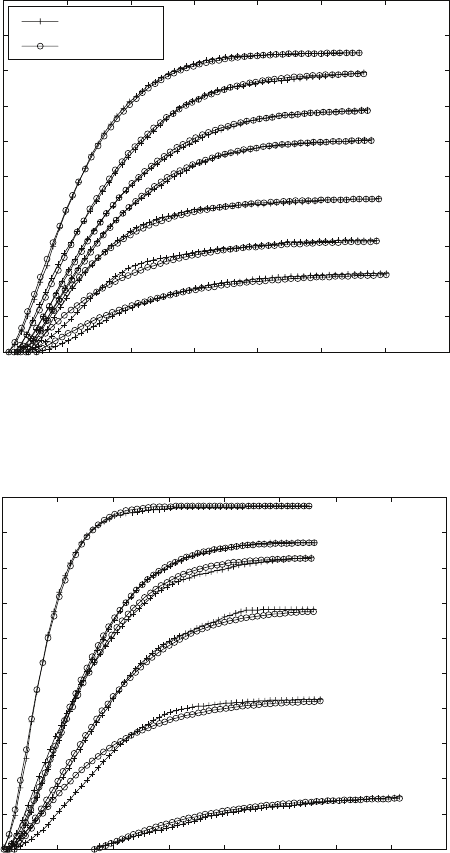

In Fig. 6.16, the calculated and the experimental transformation kinetics

are compared.

6.7.3 β21s

The experimental resistivity curves can be recalculated to give the amount of

α phase versus time (Fig. 6.2d). The recalculation is based on the quantitative

X-ray analysis after the resistivity experiments and assuming, not verified

strictly for this alloy, a linear relation between the resistivity signal and the

amount of the α phase at constant temperature. Remember that the curves

Amount of α phase (vol. %)

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Experimental

Calculated

01020304050

Time (sec)

750 °C

800 °C

850 °C

900 °C

925 °C

950 °C

975 °C

6.16

Experimental and calculated kinetics of the β to α + β

transformation at different temperatures for Ti-8Al-1Mo-1V alloy.

The Johnson–Mehl–Avrami method 155

for 600 and 500 °C trace only the first stages of the transformation and do

not present the entire transformation until phase equilibria are achieved.

The diffusion mobility of molybdenum and niobium in the β phase,

especially at low temperatures, should have influence or the control of the

overall transformation rate. In β titanium, the diffusion coefficient of

molybdenum is slightly lower than the diffusion coefficient of niobium.

Since larger redistribution of molybdenum is required (see Fig. 5.7b) and

because of the lower diffusion coefficient of molybdenum in the β phase,

one may suggest that the molybdenum diffusion in the β phase controls the

transformation. The diffusion distances of molybdenum in the β phase are

calculated for the different ageing treatments (see Table 6.8). The calculated

diffusion distances can be used only for approximate estimations of the

degree of transformation, because the amount of molybdenum that needs to

diffuse increases as the temperature decreases. The diffusion distance over

two hours at 650 °C is 1.22 µm. The experiments show that the β to α + β

phase transformation is completed after two hours at 650 °C. However, two

hours are not enough for the completion of the phase transformation at 600

and 500 °C. This may well be explained with the much shorter diffusion

distances after two hours at these temperatures (see Table 6.8). In simple

terms, the diffusional mobility is low, and therefore longer times are required.

The diffusion distance over 54 hours at 500 °C (1.07 µm) is similar to the

diffusion distance over two hours at 650 °C. Hence, these two ageing regimes

are equivalent in terms of the diffusion distance for the alloy. However, at

the lower temperature of 500 °C, a higher amount of molybdenum needs to

diffuse. It is therefore not surprising that, while at 650 °C the transformation

is completed after two hours, at 500 °C at least 54 hours are necessary. Ten

hours at 600 °C give a diffusion distance of 1.61 µm and so the experimental

results show that the phase transformation is completed. The correlation of

the calculated diffusion distances with the experimental results obtained

indicates that, at temperatures below 650 °C, the β to α + β phase transformation

is controlled mainly by the diffusion of molybdenum in the β phase.

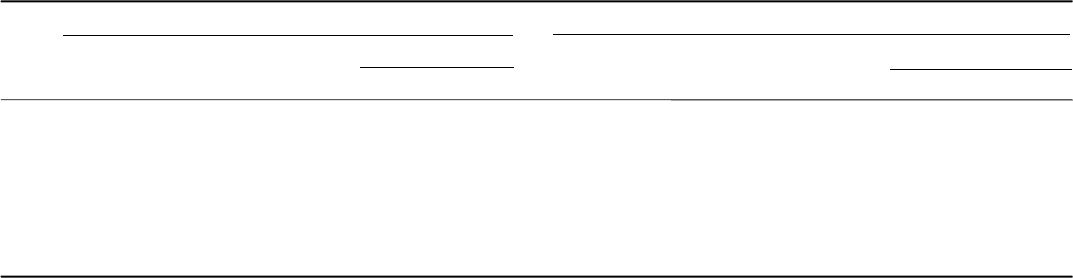

For 750, 700 and 650 °C, the experimental measurements are described

very well by single straight lines (see the example ln(ln(1/(1 – y))) plot in

Table 6.8

Calculated values of the diffusion distance of molybdenum in β21s

Ageing Ageing time Diffusion coefficient,

Dt

(µm)

temperature (°C) (hours)

D

(m

2

·s

–1

)

650 2 2.07×10

–16

1.22

600 2 7.20×10

–17

0.72

600 10 7.20×10

–17

1.61

500 2 5.86×10

–18

0.21

500 18 5.86×10

–18

0.62

500 54 5.86×10

–18

1.07

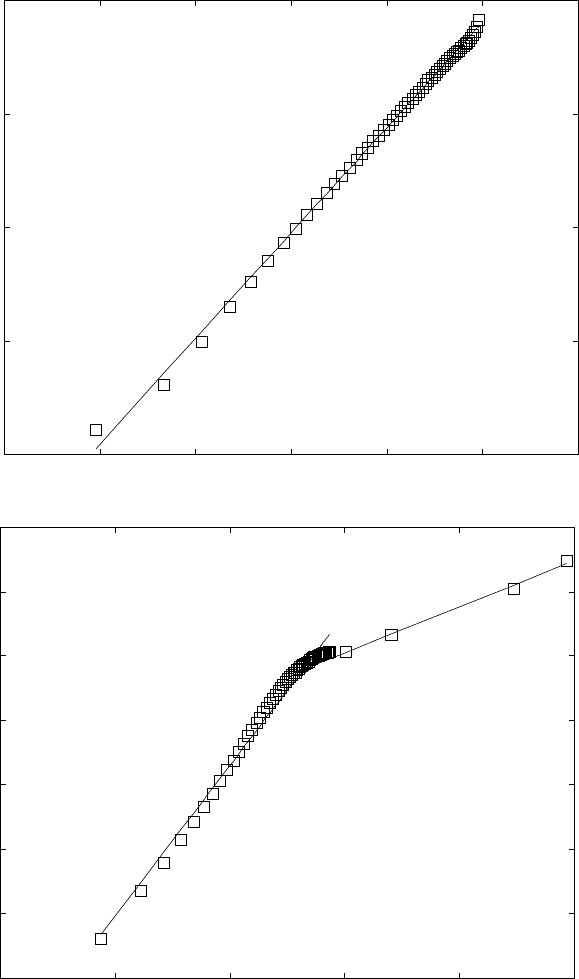

Titanium alloys: modelling of microstructure156

Fig. 6.17a). The Avrami index, n, for the temperatures of 750, 700 and

650 °C, is 1.78, 1.86 and 1.86, respectively. These characterise the mechanism

of the transformation when β grain boundaries are preferable nucleation

sites for α phase, which has a lamellar morphology.

For lower temperatures (600 and 500 °C), data from both resistivity and

additional ageing are traced within the framework of JMA theory. The data

for these temperatures apparently consist of two parts, which can be fitted

with two separate lines (see Fig. 6.17b). In the first stage of the transformation,

the data fit corresponds to straight lines with slopes 1.20 and 1.17 for 600

and 500 °C, respectively. However, with time increase, there is an obvious

tendency for change of the line slope (see Fig. 6.17b) to lower values of

about 0.4 and 0.36 for 600 and 500 °C, respectively. Other near-β titanium

alloys (Ti 10-2-3 and β-CEZ) have similar changes. At these low temperatures,

the β to α + β transformation is in conditions of (i) nucleation including

homogeneous nucleation (mainly at the first stages), and further (ii) slow

diffusion controlled growth of very fine α plates. The change of the

transformation mechanisms is gradual, at around 650 °C.

The derived JMA parameters allow the transformation kinetics to be

calculated (Fig. 6.18).

6.8 Time–temperature–transformation diagrams

6.8.1 Ti 6-4 and Ti 6-2-4-2

Using the resistivity data on the kinetics of β to α + β transformation at

different constant temperatures, complete isothermal transformation diagrams

can be designed. These diagrams, also known as time–temperature–

transformation (TTT) diagrams, give the relationship between the temperature

(plotted linearly) and the time (plotted logarithmically) for a fixed fractional

amount of transformation to be attained. Such diagrams are usually used in

alloy heat-treatment practice. In literature, usually, only the ‘start’ and the

‘end’ of the transformation are plotted in these diagrams. However, times

corresponding to the very start and the very end of the transformation are

difficult to be measured experimentally. For this reason, in calculations, we

can use transformed fractions of 5 and 95% for the start and the end of the

transformation, respectively (Fig. 6.19). For these titanium alloys, the ‘end

of transformation’ does not correspond to when the initial phase (β phase)

completely transforms to the new phase (α phase). At each temperature, a

different phase composition (α + β mixture) is the final product (see Section

6.6). Hence, the start and the end of the transformation should not be read as

5 and 95% of the α phase but as 5 and 95% degree of transformation. Iso-

lines are calculated and plotted on the same diagrams (Fig. 6.19), showing

the real amounts of the α phase.

The Johnson–Mehl–Avrami method 157

n

= 1.86

234 5678

In(

t

)

(a)

In(In(1/(1–

y

)))

2

0

–2

–4

–6

2 4 6 8 10 12

In(

t

)

(b)

In(In(1/(1–

y

)))

1

0

–1

–2

–3

–4

–5

–6

n

= 0.36

n

= 1.17

6.17

Plots of ln(ln(1/(1–

y

))) against ln(

t

) for deriving the Johnson–

Mehl–Avrami parameters for β21s alloy at (a) 700 and (b) 500 °C.

700 °C

500 °C