Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AMERICAN STORIES

128

storytelling was real; it was what she thought about all the time, imagining the

whole world—sticks, trees, birds, and rivers—all talking all at once:

I came in from play one day and told my mother how a bird had talked to

me with a tail so long that while he sat up in the top of the pine tree his tail

was dragging the ground. . . . Another time, I dashed into the kitchen and

told Mama how the lake had talked with me, and invited me to walk all

over it. . . . Wasn’t that nice?

My mother said that it was. My grandmother glared at me like open-

faced hell and snorted.

“Luthee!” (She lisped.) “You hear dat young’un stand up here and lie like dat?

And you ain’t doing nothing to break her of it? Grab her! Wring her coat tails

over her head and wear out a handful of peach hickories on her back-side!”

“Oh, she’s just playing,” Mama said indulgently.

“Playing! Why dat lil’ heifer is lying just as fast as a horse can trot.”

Zora knew she “did not have to pay too much attention to the old lady and so

I didn’t. Furthermore, how was she going to tell what I was doing inside? I

could keep my inventions to myself, which was what I did most of the time.”

In all of America, there were few places like Eatonville, where black people

were their own mayors and police chiefs, where black and white folk, who

lived nearby in Maitland, got along extraordinarily well. This was the kind

of home where a black girl could dream uninhibited by color, although in her

father’s opinion, “It did not do for Negroes to have too much spirit.”

Jim Crow was the big boss of the South, and segregation was his rule. With

physical violence a steady threat for any southern blacks who did not mind

their place, and with few good job opportunities in the South but lots of new

factory jobs in the North, the natural solution was to pick up and move. By

1920, every northern city that had good jobs had good music. Detroit with its

cars, Chicago with its meat, Cleveland and Pittsburgh with their steel, and New

York City with everything attracted more than 1 million “New Negroes,” who

were bound to change the sound, the look, and the feel of the places where

they landed. The trumpet-blowing Louis Armstrong went from New Orleans

to Chicago and started touring during the 1920s. The blues-singing Bessie

Smith went from Tennessee to the North and back again as she toured and

recorded for more than twenty years. Armstrong and Smith recorded music

together in New York City. The poetry-wielding Langston Hughes went from

Kansas to New York, which became a homebase for his own itinerant life that

included trips to Moscow, Paris, Africa, and Los Angeles. He sampled the

world, brought it back home, and set it to words. A favored destination for

those who could afford it, or at least thought they could afford it, was Harlem

in New York City, described by historian Robert Hemenway as “a city within

129

THE 1920S

a city . . . the cultural capital of black America.”

22

By the end of World War

I, Harlem had more than 100,000 black residents. Harlem was hope; Harlem

was jazz and jazzy poetry; Harlem had swing; the Harlem Renaissance was a

period of black freedom and creative expression without oversight or permis-

s

ion. Zora Neale Hurston arrived in 1925, twenty-one years after her mother’s

death and twenty years after she had first set out on her own, unwanted by her

father and tolerated by an older brother only as a house cleaner.

A double dose of spirit and talent and what her mother had called “travel

dust” had put Hurston on the roads from Eatonville to Jacksonville and back

home again, only long enough to find the “walls were gummy with gloom”

caused by a dislikable stepmother. The antagonism between Zora and her

father’s new wife finally erupted into an all-out brawl, with hitting, scratching,

spitting, screaming, and hair pulling: “I made up my mind to stomp her, but at

last, Papa . . . pulled me away.” Although her father had done little to coddle

Zora, he would not totally abandon her either. Her stepmother said, “Papa had

to have me arrested, but Papa said he didn’t have to do but two things—die

and stay black.” At the age of fourteen, Zora Hurston left Eatonville for good,

seeking as much fortune as could be scraped from a nation that had not yet

read her name, had not yet read her talent.

For

ten years fortune played peek-a-boo. Hurston learned how to work

and how to scrounge, and she later remembered, “there is something about

poverty that smells like death. . . . People can be slave-ships in shoes.” Hurston

cleaned houses, nannied, stiff-armed amorous employers, attended schools

when and where she could, and toured with a troupe of traveling actors as

the personal attendant to the star of the show. These were people who lived

words, who made their bodies talk, though her southern bumpkin tongue was

just as impressive:

In the first place, I was a Southerner, and had the map of dixie on my

tongue. They were all northerners except the orchestra leader, who came

from Pensacola. It was not that my grammar was bad, it was the idioms.

They did not know of the way an average southern child, white and black,

is raised on simile and invective. They know how to call names. It is an

every day affair to hear somebody called a mullet-headed, mule-eared, wall-

eyed, hog-nosed, gator-faced, shad-mouthed, screw-necked, goat-bellied,

puzzle-gutted, camel-backed, butt-sprung, battle-hammed, knock-kneed,

razor-legged, box-ankled, shovel-footed, unmated so and so! . . . Since that

stratum of the southern population is not given to book-reading, they take

their comparisons right out of the barn yard and the woods.

The theater tour ended for Hurston in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1916.

If a giant motion picture camera had been hung from the sky over the east

AMERICAN STORIES

130

coast of the United States in the 1920s, it would have shown two dust tracks

on the road: one made by white people heading to southern Florida, the other

by black people heading north. Zora Neale Hurston and Al Capone could have

waved at each other in passing, he on the way to Miami, she on the way to

Harlem. For generations, Florida had attracted the wealthy, the elderly, and

the sick. But in 1896, an oil tycoon named Henry Flagler—a partner of John

D. Rockefeller and part of the Standard Oil Trust—financed the building of

the Florida East Coast Railroad all the way to sultry, breezy Miami. And the

boom was on. Over the next twenty years, workers drained the surrounding

Everglades and built the Tamiami Trail, a 238-mile highway that ploughed

right through the swampy heart of the peninsula from Miami west to Naples,

connecting the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf Coast. The workers slept in elevated

cabins that kept their feet from becoming alligator or snake feed. Now middle-

class Americans could ride a train or put-put-put in their Model Ts and GMCs

for a little Florida sun. Out in the bays, rum runners delivered Jamaican rum

for the speakeasies, clubs, and resorts that blossomed in the speculative frenzy

that had northerners buying empty lots, bungalows, and houses in subdivi-

sions.

Credit flowed like wine, just as it gushed and geysered on Wall Street.

Although some people prophesied collapse, the boosters, the developers, the

real estate jobbers, and the bankers kept on selling.

I

n 1926, a hurricane blasted southern Florida with 125-mile-per-hour winds

and threw a hungry tidal wave over more than 13,000 new houses. At least

115 people died in Miami, and another 300 drowned in the crashing waves,

mostly poor Latino migrant laborers who were too poor to have the means

for escape. Their bodies got stacked in heaps and burned. Two years later, the

land boom went bust, a bitter taste of the hard years to come. Florida, how-

ever

, had etched itself in the nation’s mind as the destination for vacation and

migration. A slow urban, suburban, and exurban sprawl was swallowing the

quaint towns of Zora Hurston’s childhood. But before Walt Disney built castles

in the sand for Mickey and Minnie Mouse in the 1950s, before Eatonville

got absorbed by Orlando’s asphalt, before the folktales told at Joe’s Country

Store went silent, Zora would get a college education at Barnard College in

New York, study under the master anthropologist Franz Boas, and return to

the South under his tutelage to collect the old-time tales and to tease out the

mysteries of hoodoo.

After

parting company with the actors in 1916, Hurston stayed on a while

in Baltimore and then skipped to Washington, DC. In between stints as a

waitress, a manicurist, and once again a maid, she found the wherewithal

to attend night classes and then Morgan College, for she was determined to

get an education. “This was my world,” she said to herself, “and I shall be in

it, and surrounded by it, if it is the last thing I do on God’s green dirt-ball.”

131

THE 1920S

Though she did not fit in at Morgan, which catered to a decidedly middle-class

group of students, her work gained her the opportunity to enroll at Howard

University, which “is to the Negro what Harvard is to the whites,” where she

earned a two-year degree in English in 1920. Introductions to the witty and

well connected at upwardly mobile Howard University helped Hurston with

her next step up the socio-economic ladder.

By 1920, black Americans were divided over the best means to gain equal-

ity

. Should they persist with established channels, cooperation with whites,

petitions, demonstrations of worth, and patience? Or should black Americans

give up the goal of integration and simply go their own way, create their own

black society, a nation within a nation—or perhaps a new nation somewhere

else, a grand resettlement? W.E.B. DuBois, the leading voice of the NAACP,

advocated the first method, still committed in the 1920s to cooperation, though

no less vehement or forceful in his demands for justice.

Rising

like a black Moses from the colonial streets of Kingston, Jamaica,

Marcus Garvey spoke in a different voice. Arriving in Harlem in 1916, Garvey

learned to move and speak like a preacher from the master of posture and

pose, America’s first pop-culture evangelist, Billy Sunday (a fevered foe of

alcohol and one-time golf chum of Babe Ruth). Schooled in pomp, Garvey

dressed in colorful uniforms and carried a ceremonial sword. He opened the

Harlem doors of his Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in

1917 in the aftermath of a disgusting race riot in East St. Louis where white

people rampaged through the African-American district, killing at will, toss-

ing

children back into burning buildings. Just as American doughboys were

suiting up to “make the world safe for democracy,” black people in America

were being brutalized. Rage, indignation, and injustice gave momentum to

Marcus Garvey’s cry: “One God, One Aim, One Destiny.” Garvey wanted

black people to unify and to take care of their own, in particular by start-

ing

their own businesses, their own banks and investment funds, their own

newspaper—the Ne

gro World—and a shipping line, Black Cunard. By 1919,

Garvey had 750,000 followers, ships in the water, and his movement was

heading for disaster. His calls for an entirely black nation in Africa—free

from any white colonial control—scared the authorities, and J. Edgar Hoover

of the Federal Bureau of Investigation was busy spying on Garvey, literally

sabotaging Black Cunard ships by mixing junk into the gasoline. Worse, with

millions of dollars coming into UNIA and the shipping company, Garvey

began to embezzle from his own empire. Sensing conspiracy all around him

(with good reason), he made an imaginative leap and met with the leader of

the Ku Klux Klan—the man in whom Garvey assumed real and true power

was vested in white America. The news that the self-styled leader of the first

black power movement in the United States was negotiating with the grand

AMERICAN STORIES

132

wizard of the KKK lost Garvey thousands of supporters. Before long, Garvey

was charged and convicted of embezzlement and sentenced to five years in

prison. In 1927, before the end of his term, President Coolidge pardoned him

and deported him back to Jamaica.

Some

of Zora Neale Hurston’s first published writing appeared in Gar-

vey’

s Negro World in 1920, which at the time had more subscribers than the

NAACP’s Crisis. Hurston’s gratitude to Garvey for the chance to publish

lasted

no longer than Garvey’s reputation could sustain: in 1928, Hurston

laughed at Garvey for having found greatness only in his great ability to steal

from his own people. By that time Hurston was becoming something of a

phenomenon in her own right. She had moved to Harlem in 1925, enrolled at

Barnard College (the female wing of Columbia University) as the only black

student in a sea of rich, white faces, and enchanted professors, fellow artists,

and even a wealthy patron—Charlotte Mason, who demanded to be called

“Godmother” by anyone accepting her money. At Barnard, Hurston made the

professional choice to study anthropology rather than English, largely because

of the charisma of Franz Boas, an intense German-born professor who headed

a variety of famous studies and students: sending researchers into the Pacific

Northwest to record Native American languages and myths and promoting the

adventurous career of Margaret Meade, who sailed to American Samoa and

examined adolescence as a cultural, rather than biological, phenomenon. Boas

was a staunch critic of eugenicists, the scientists who wanted to create perfect

people by selectively weeding out “undesirables” through sterilization, and

through Boas’s training of a new generation of anthropologists he combated the

racism and biases inherent in eugenics. His social vision appealed to Hurston,

and with his intellectual guidance and Godmother’s money, she went back to

Florida in 1927 to collect folk tales and to study hoodoo. There she heard of

the most famous hoodoo priestess in New Orleans—Marie Leveau, “the queen

of conjure” who once charmed a squadron of police into assaulting each other

instead of arresting her. When not in Boas’s classroom or wading through the

magic tales of the South, Zora was collaborating with Langston Hughes on a

number of projects, going to parties and speakeasies, and generally drinking

in the effervescence of Harlem at the zenith of its renaissance.

Zora Neale Hurston brought the country to the city. Her Eatonville back-

g

round was central to just about everything she wrote, including most of her

essays, plays, novels, and ethnographic studies. In 1928, looking back at her

childhood, she recalled that other blacks in Eatonville had “deplored any joy-

f

ul tendencies in me, but I was their Zora nevertheless. I belonged to them, to

the nearby hotels, to the country.” When she left monochrome Eatonville and

ventured into multicolored Jacksonville, Hurston discovered that she “was now

a little colored girl . . . a fast brown—warranted not to rub nor run.”

23

From that

133

THE 1920S

point forward, she would experience what DuBois in 1903 called “this double-

consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of

others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused

contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness,—an American, a Negro; two

souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark

body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

24

Hurston

made sure to emphasize that she was “not tragically colored. There is no great

sorrow dammed up in my soul nor lurking behind my eyes. I do not belong to

the sobbing school of Negrohood who hold that nature somehow has given them

a low-down dirty deal and whose feelings are all hurt about it.” In 1928, when

she wrote these words in an essay titled “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” she

was not giving in to anyone else’s petty race tyrannies or degrading demands.

Instead, she saw a “world to be won and nothing to be lost.”

25

For a time, Zora Neale Hurston won that world. She took first prizes for her

plays and earned money for her essays. In the 1930s, she began publishing books,

most notably (to the English teachers who now assign it) Their Eyes Were Watch-

i

ng God, a story about one woman’s shot at self-fulfillment told in the dialect

of Hurston’s old South. Big-name newspapers and magazines gave her books

good reviews, but ultimately her color caught up with her. As author Mary Helen

Washington explained in the foreword to a 1990 rerelease of Their Eyes Were

Watching God, “one white reviewer in 1937 [said he] had difficulty believing

that such a town as Eatonville, ‘inhabited and governed entirely by Negroes,’

could be real.”

26

When the novels of white authors like Ernest Hemingway, F.

Scott Fitzgerald, and Sinclair Lewis sold in the hundreds of thousands, not one

of Hurston’s books sold more than 5,000 copies before her death. She never

earned even as much as $1,000 in royalties for a single volume, at a time when

Babe Ruth was making more than $30,000 a year for swinging a bat. By 1960,

she was living in Georgia, penniless and on state assistance. After she died that

year, some of her unpublished writings were saved by a firefighter who put out

the smolder in a heap of her papers that the apartment manager was torching.

This woman who once sarcastically styled herself “Queen of the Niggerati,” this

woman whom fellow writer Langston Hughes said was “full of side splitting

anecdotes, humorous tales and tragi-comic stories”

27

to the enjoyment of all in

her glow, this black woman from Eatonville, Florida, died in relative obscurity

and was buried in an unmarked grave.

Though her own generation had largely abandoned her, she never meant to

be tragic nor tragically taken, so it may be best to remember her own version

of a tombstone epitaph. “In the main,” Zora Hurston wrote, “I feel like a brown

bag of miscellany propped up against a wall. . . . Pour out the contents, and

there is discovered a jumble of small things priceless and worthless. . . . On

the ground before you is the jumble it held—so much like the jumble in the

AMERICAN STORIES

134

bags, could they be emptied, that all might be dumped in a single heap and

the bags refilled without altering the content of any greatly. A bit of colored

glass more or less would not matter. Perhaps that is how the Great Stuffer of

Bags filled them in the first place—who knows?”

28

In Cars, on Roads, to Cities

The newspaper writer Heywood Broun captured the ebullient mood of the

era when he said, “The jazz age was wicked and monstrous and silly. Unfor-

tunately

, I had a good time.”

29

While Babe Ruth, Al Capone, and Zora Neale

Hurston were having a good time batting, boozing, capering, and writing, the

rest of the nation paid the Babe and Capone a lot of attention and Hurston at

least a little. Other Jazz Age Americans had to content themselves, typically,

with less: less money, less crime, and maybe less fun. After all, a lot of people

still lived on farms, many wishing they could sample the sparkling neon lights

and spicy clubs of the big cities a bit more often, or at least once. One farm

wife got interviewed in 1919 and was asked why she owned a car but no

bathtub. She responded, “Why, you can’t go to town in a bathtub.”

30

Roads and cities were not new to America. As far back as the 1820s, Henry

Clay of Kentucky had been arguing that the federal government ought to be

in the business of building roads so that goods from out west could get to the

markets back east a whole lot quicker and cheaper. But it was not until 1916

that the federal government passed a law offering the states one dollar for

each state dollar spent to pave roads in the interest of rural mail delivery. The

objective was limited, but the effects were limitless. Along those roads that

the states built, like the Tamiami Trail in Florida, people toured and migrated.

Some went from city to city. Some went from farm to farm. But of those

who actually packed up and moved, the major step was from farm to city. In

fact, 1920 marked a turning point: in the census that year, more people were

recorded living in cities (of at least 2,500 or more) than in rural districts and

small towns. In search of jobs, fun, or simply something new, Americans

chose the mixed joys of urban jungles.

Notes

1. Communication and Consequences: Laws of Interaction (Mahwah, NJ: Law-

rence Erlbaum, 1996), 152.

2.

Peter Collier and David Horowitz, The Fords: An American Epic (San Fran-

cisco: Encounter

, 2002), 34.

3. For the full text of the 1927 Indiana law, see “An Act to provide for the sexual

sterilization of inmates of state institutions in certain cases,” S. 188, Approved March

11, 1927,

www.in.gov/judiciary/citc/special/eugenics/docs/acts.pdf.

135

THE 1920S

4. Edwin Black, War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America’s Campaign to

Create a Master Race (New York: Thunder’s Mouth, 2003), 400.

5. Maureen Harrison and Steve Gilbert, eds., Landmark Decisions of the United

States Supreme Court, Buck v. Bell, May 2, 1927 (Beverly Hills: Excellent, 1992),

48–52.

6.

Gerald Leinwald, 1927: High Tide of the 1920s (New York: Four Walls Eight

Windows, 2001), 78.

7. Quoted in Nicholas E. Tawa, Supremely American: Popular Song in the 20th

Century (Lanham, MD: Scarecrow, 2005), 58–59.

8. Leinwald, 1927, 165.

9.

Laurence Bergreen, Capone: The Man and the Era (New York: Touchstone,

1994), 83.

10. Leinwald, 1927, 134.

1

1. Robert Sobel, Coolidge: An American Enigma (Washington, DC: Regnery,

1998), 313.

12.

David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression

and War, 1929–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 33.

13. Leinwald, 1927, 3.

1

4. Robert Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (New York: Simon &

Schuster, 1992), 222.

15. Quoted in Roger Kahn, Memories of Summer: When Baseball Was an Art, and

Writing About It a Game (Lincoln, NE: Bison, 2004), 51.

16. Ber

green, Capone, 262.

1

7. “What Elmer Did,” Time, December 6, 1948,

www.time.com/time/magazine/

article/0,9171,853607,00.html.

18. Cyndi Banks, Punishment in America (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2005),

76.

19. Ber

green, Capone, 524.

20.

Jeffrey Toobin, “The CSI Effect: The Truth About Forensic Science,” New

Yorker, May 7, 2007, 32.

21. All

excerpts from Zora Hurston’s autobiography are taken from Zora Neale

Hurston, Dust Tracks on a Road (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippencott, 1942).

22.

Robert E. Hemenway, Zora Neale Hurston: A Literary Biography (Urbana:

University of Illinois Press, 1980), 29.

23.

Zora Neale Hurston, “How It Feels to Be Colored Me,” World Tomorrow, May

1928, 215–216.

2

4. W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk (New York: A.C. McClurg, 1903), 3.

25. Hurston, “How It Feels,” 216.

26. Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God (New York: Harper and

Row, 1990), vii.

27. Langston Hughes, The Big Sea (New York: Knopf, 1940), 239.

28. Hurston, “How It Feels To Be Colored Me,” 216.

29. Alistair Cooke, Talk About America (New York: Knopf, 1968), 74.

30. Franklin M. Reck, A Car Traveling People: How the Automobile Has Changed

the Life of Americans—A Study of Social Effects (Detroit: Automobile Manufacturers

Association, 1945), 8.

INTO THE GREAT DEPRESSION

8

Into the Great Depression

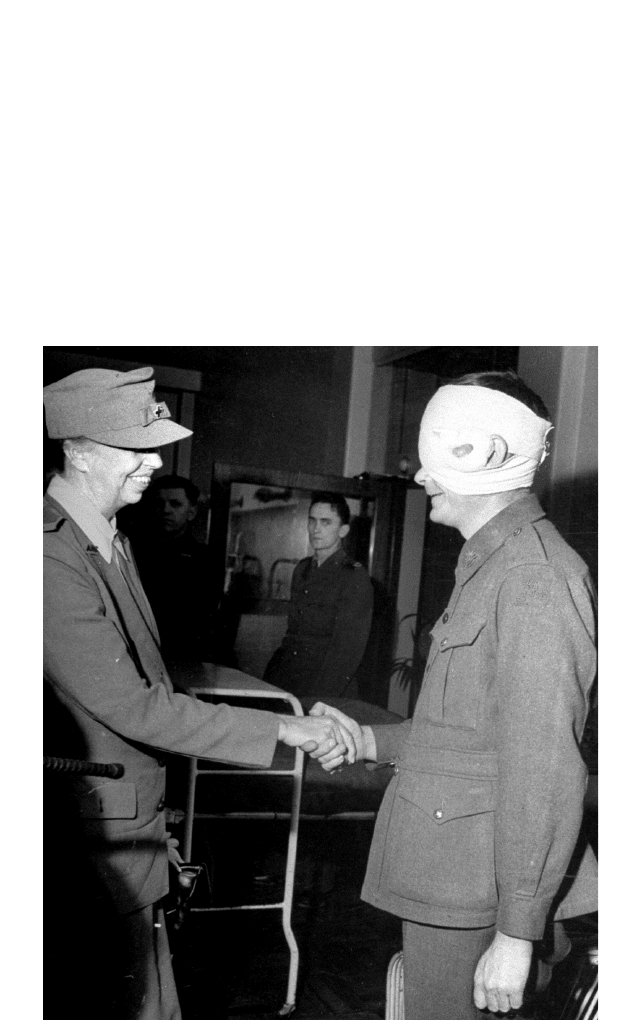

Eleanor Roosevelt shakes a wounded soldier’s hand, 1943.

(George Silk/Getty Images)

137