Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

AMERICAN STORIES

148

Sanchez recalled that “it was so dark and dusty [he] couldn’t find the

entrance” to the radio station where he had been heading next. After groping

around in blasts of wind that felt like somebody was “sandblasting” his face,

he made it into the radio station, KGNO, and crawled up the pitch-black

stairwell to the second floor where he waited for more than three hours. A

group of begrimed people stumbled into his temporary sanctuary, detoured

from their trip to a movie. Caught in the gale of dirt, they had “abandoned their

car, held hands, and feeling the curb, found their way to KGNO.” Not wanting

his mother to worry about him, Sanchez headed home as soon as possible. He

remembered others dying in subsequent years of dust-induced pneumonia,

and though he survived to tell the tale, his family’s circumstances were bleak:

“Our homes were made of old lumber that the railroad had thrown away. No

one had storm windows or doors so the dust just sifted in. My mother had to

put wet rags over the windows and doors to keep some of the dust out of the

air so that we could breathe.”

The

gritty swirls of dust marched across the middle of the continent, strip-

ping

paint from new cars and houses, crackling with enough static electricity

to make metal poles shimmer and snap. Although the center of the dust bowl

was in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, dirt from storms like this reached as far

as Washington, DC, and New York City. There were even instances of dust

bowl sand drifting out on the jet stream to land on ships’ decks at sea. The

six-year drought ended in 1937. Two years later, The Wizard of Oz, starring

Judy Garland as Dorothy, was released. Although L. Frank Baum’s Oz stories

were three decades old, the opening dust bowl scene must have seemed more

documentary than fantasy to the sand-blasted sodbusters, railroad hoppers,

store clerks, Okies, and general nesters who toughed out six years of drought

and dust.

During

the 1930s, President Roosevelt’s New Deal administration imple-

mented

all sorts of programs designed to improve life on the farm. Minimum

prices were guaranteed for a variety of meats, vegetables, and grains. The

Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) paid southern farmers to put

hundreds of thousands of acres of cotton under the plow, literally lowering

production to raise prices—then the AAA paid plantation owners in cash for

the ruined cotton (during the decade, farm prices rose by 40 percent). The

Rural Electrification Agency brought electricity to outlying farmhouses no

private utility company would have dreamed of supplying at so much expense

for so little financial return. The Tennessee Valley Authority, the largest

river-damming irrigation project in the history of the nation, provided jobs,

corrected soil erosion, diminished malaria breeding grounds, and provided

steadier electric power throughout the South. But not everyone in the southern

Midwest would benefit from New Deal programs.

149

INTO THE GREAT DEPRESSION

Sharecroppers both black and white provided the bent-backed, cotton-

picking labor that slaves had done for 200 years. Sharecroppers owned noth-

ing

but a few clothes—and sometimes a pot, a fork, and a Bible—and they

owed one-half of their cotton crop to the plantation owner in payment for

the dubious pleasure of working the land, which left a starving share for the

cropper’s family. When the AAA started to send checks to farmers in 1934 to

slow cotton production, the plantation owners kept the cash for themselves,

rarely passing any down to tenants or sharecroppers. An insurgent union called

the Southern Farmers’ Tenant Union (SFTU) formed slowly and painfully to

fight for some crumb of the greenback pie being delivered to the landowners.

Segregated tradition gave way to integrated need, and the SFTU became a

biracial movement: hunger and oppression looked black and white. In ugly

response, owners of large farms took two actions: first, they worked with local

sheriff’s departments to beat and shoot SFTU organizers throughout the South,

once breaking into a church and blasting worshippers in the back as they tried

to run; and second, they told their congressmen in the Democratic Party to

pressure President Roosevelt not to help the SFTU. Roosevelt agreed, believing

he could not push through other elements of his New Deal without the sup-

port

of his party’s southern wing. In 1935, Congress passed the Wagner Act,

giving workers the right to collective bargaining, the right to form unions with

federal protection. But the Wagner Act did not cover southern tenant farmers

and sharecroppers, and the Farmers’ Tenant Union crumbled and sank back

into the cotton fields by the end of the decade. Northern steel and autoworkers,

however, flooded into the newly created Congress of Industrial Organizations,

a union for unskilled laborers. Under the leadership of its president, John L.

Lewis, spark-scarred machine hands gained higher wages and shorter hours.

In the North, workers might be poor but they could vote, so they had power

over their congressmen. In the South, workers were poor and could not vote,

excluded by dirty tricks like the poll tax, usually a one-dollar registration fee

that sharecroppers simply could not pay. Without money and without the vote,

poor southerners bent back under the lash of tradition.

Also

during the 1930s, under prompting from labor unions like the Ameri-

c

an Federation of Labor and from local welfare agencies, approximately

400,000 Mexicans and Mexican-Americans—many of them U.S. citizens

born in this country—were forcibly deported as repatriados, “the repatriated,”

a word used insincerely and inaccurately. One-third of all Spanish-speaking

residents of Los Angeles were deported, along with hundreds of thousands

of men, women, and children from Arizona and Texas. Only ten years later,

when more than 110,000 Japanese-Americans were forced into concentra-

tion

camps during World War II, the U.S. government would entirely reverse

course under the bracero program, which imported Mexican laborers to work

AMERICAN STORIES

150

the fields of the West from which the Japanese had been plucked. When they

were needed as cheap labor, Mexicans were invited—officially and unof-

ficially—to

enter the United States; when the economy slumped, Mexicans

and Mexican-Americans were chased away.

The dust bowl was no one’s friend, certainly not gentle to the hangers-on

at the fringes of the American economy. However, people of all colors and

creeds found a powerful friend and ally in the White House, though it was not

always the president. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt—niece to former president

Theodore Roosevelt, former volunteer dance teacher at a settlement house

in New York City’s Lower East Side, journalist writing a daily column titled

“My Day”—coolly ignored the angry comments of racists and conservatives

as she urged her husband to make the New Deal an equal deal for all.

Eleanor Roosevelt: Before the Depression

Eleanor Roosevelt was anything but common, but she championed the com-

mon

causes of common people. Not since Dolley Madison had smoothed

political feelings, thrown festive soirees, and saved an original oil painting

of George Washington from the flames of British temper in 1814 had there

been as independent and powerful a woman in the White House as Eleanor

Roosevelt.

S

he was born in 1884, the daughter of Elliot Roosevelt, the dashing

youngest brother of Theodore, and his wife, Anna. Eleanor’s childhood had

equal parts tragedy and chance. For tragedy, her father Elliot’s alcoholism

competed with her mother Anna’s distaste for Eleanor’s physical features,

namely a set of buckteeth. Her father abandoned her all too often for hunting

getaways and bars, literally leaving young Eleanor on the street outside “his

club” one afternoon until the establishment’s doorman saw her and ordered

a taxi to take her home.

15

Her mother abandoned little Eleanor from the

outset, unsure of how to raise a bucktoothed girl in an upper-crust society

that demanded conventional beauty of its women. But the Roosevelt family’s

iron will braced Eleanor’s spirit to withstand the dwindled love of a besotted

father and disappointed mother. Eleanor could and would care for herself,

and she was not without allies or friends. Raised for a time by her maternal

grandmother in New York City after Anna Roosevelt died in 1892, Eleanor

first found sympathetic friends at the age of fifteen in England at an exclusive

school, Allenswood, presided over by the gifted Madame Souvestre. There,

Eleanor met other young women of means and minds, and under Madame

Souvestre’s careful tutelage, she realized that there was room in the world

for women of soaring spirit.

S

oon after returning from England, Eleanor went to a party she did not want

151

INTO THE GREAT DEPRESSION

to attend: her own. For members of old money, landed families, a coming-

of-age ball was held to announce adulthood. In Eleanor’s case, this meant

an evening of unwanted small talk and the recognition that her new-found

freedom was not long to last because the party also heralded her availability

for marriage. Having enjoyed classic literature and tours of Europe with

Madame Souvestre, Eleanor knew that marriage would entail the confines

of home, weighted down by the children she would be expected to have.

One starry-eyed suitor turned out to be much better than her fears. This was

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a fifth cousin and Harvard student who knew

what he wanted: to marry Eleanor and to be president of the United States.

She elected him husband in 1905, twenty-eight years before the rest of the

country elected him president.

F

or ten years, Eleanor and Franklin shared an intimate love, though he was

soon distracted by his ambition. In 1910, Franklin was elected to the New York

State Senate and in 1913 landed the same federal-level job his older cousin,

Theodore, had held: assistant secretary of the navy. To get these jobs and keep

them, Franklin had to flash his delightful smile at innumerable hand-shaking,

martini-sipping functions. Meanwhile, Eleanor was in the midst of birthing

and raising five children under the domineering eye of mother-in-law Sara,

who had never wanted any competition for her son’s love. Sara Roosevelt

hovered. She went so far as to buy adjoining apartments for herself and for

Franklin and Eleanor; then she had doors installed to join the apartments on

every floor.

Eleanor Roosevelt handled the children, the meddling mother-in-law, and

the attention-seeking husband with grace and charm. But in 1915, Franklin

complicated their domestic tranquility by having an affair with his wife’s social

secretary. Eleanor discovered the truth when, after he returned from a tour of

war-torn Europe, she unpacked his suitcase and found a bundle of love letters

that she could not resist reading. After confronting him about the affair, which

Franklin promised to end, Eleanor said she would remain in the marriage—a

necessity for a man with major political ambitions. In return (though nearly

a decade later), Franklin built her her own house, Val Kill, right down the

road from the family mansion, Hyde Park, in New York. By the late 1910s,

the Roosevelts maintained a marriage as true friends, and though they often

lived apart, their public lives were intertwined.

In

1920 Franklin made an unsuccessful bid for the vice presidency, losing

to the Harding ticket and its promise of normalcy. Eleanor was there at his

side, waving, smiling, and trying to control her runaway voice, which was

high to start with and regularly took off by a shrill octave or two without her

permission. The polio virus hit Franklin in the summer of 1921 while the

family was vacationing in Maine, and once more Eleanor stood firmly by

AMERICAN STORIES

152

him, pulled back to his side by the quite literal necessity of propping him up

as he tried to regain the use of his legs. Most people who caught polio did not

suffer any paralysis, but a small minority did, and for most of them the loss

of mobility was permanent. As the years progressed, Franklin and Eleanor

resumed their separate private lives.

P

opularity from the Pulpit: Aimee Semple McPherson

Few Americans would have known who Eleanor Roosevelt was before 1928

when her husband became, much to her chagrin, governor of New York State.

Zora Neale Hurston’s name would have been slightly better known in literary

circles, but both women were invisible compared to the holy glow of Aimee

Semple McPherson. A two-time widow from Ontario, Canada, McPherson

turned people on to God by getting people to tune in to her. Discovering a

talent for revival-style preaching of a Pentecostal bent (including speaking in

tongues and faith healing), McPherson draped herself in bright white, stylish

outfits, giving congregants the unique opportunity to hear God’s word while

seeing her shapely legs. What could not be seen from the pews of her 5,300-

seat Angelus Temple in Los Angeles could be imagined by listening to her

broadcasts over KFSG radio—McPherson’s own station. Her Foursquare

Gospel movement blossomed into hundreds of churches and a groundswell

of interest in fundamentalist Christianity outside its rural crib in the South

and Midwest. More than an evangelist for the Word alone, McPherson clinked

glasses with seemingly unlikely types, like the sharp-tongued secularist H.L.

Mencken; she championed the Good Book while he guffawed at its most

fundamentalist followers. In 1925, Mencken traveled to Dayton, Tennes-

see,

to cover the trial of John T. Scopes, whom prosecutors charged with

teaching evolutionary theory in violation of a new state law. While Scopes’s

conviction was later overturned on technical grounds, Mencken had a riot-

ous

time lampooning the creationist residents of rural Tennessee for hatching

“conspiracies of the inferior man against his betters.”

16

More important to the

average American than the tabloid stories about Aimee McPherson’s side life

(including allegations of love affairs with a married man) were the food and

clothes she distributed to the needy during the Depression. The occasional

scandal chased after her, as stories true and untrue haunt all celebrities, but

Aimee Semple McPherson remained well loved and admired. She trained

women to be ministers and invited African- and Latino-Americans to sing at

her church on equal footing with white performers. The same tendency toward

charity and kindheartedness that earned the flashy McPherson an adoring

public was also at work for Eleanor Roosevelt. But where Aimee McPherson

chased after the spotlight, Eleanor Roosevelt tried to avoid its glare, at least

153

INTO THE GREAT DEPRESSION

until her husband became president. It took a severe national crisis to make

a president and first lady better known than a radio celebrity and personality

of the magnitude of Aimee Semple McPherson.

Eleanor Roosevelt: Progressive Politics in the Depression

During the Great Depression, Eleanor Roosevelt was probably the most

popular woman in the nation, better loved, perhaps, than Shirley Temple

(child star of the movies), Amelia Earhart (“Lady Lindy,” the first woman

to fly solo across the Atlantic; her airplane vanished in the South Pacific in

1937), or Claudette Colbert (another movie starlet of mischievous beauty).

Eleanor went where Franklin could not, literally and figuratively. Literally

she traveled more than 40,000 miles to view New Deal projects like hospitals

being built through Works Progress Administration funding, and she even

took a train two miles down a coal shaft to see the conditions endured by

miners—one of the class of workers offered the opportunity to join a union

under the 1935 Wagner Act. Figuratively, Eleanor Roosevelt tested the limits

of the Democratic Party’s liberalism with regard to African-Americans and

other groups on the margins of society. In 1939, for example, an upper-crust

association, the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR), refused to let

a world-class opera singer, Marian Anderson, sing at its jubilee because she

was black. After touring internationally because no major U.S. symphony

wanted a black soloist, Anderson returned to the same conditions she had

left. So Eleanor Roosevelt resigned from the DAR and found just the right

place for Marian Anderson to let loose the vocal angels: the public grounds

sprawling out at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial, where 75,000 people

showed up to listen. Every night Eleanor filled up a basket with memos meant

to pester Franklin’s presidential conscience about this or that, and she filled

the basket so full and so often that he finally told her not to put in more than

three requests a night. Eleanor promoted the cause of poor farmers, abandoned

wives with children to feed and no food in the cupboards, and just about every

other group of disadvantaged Americans. Consequently, African-Americans

in particular flocked to the Democratic Party, almost fully abandoning the

Republican ranks, the party of Abraham Lincoln. The New Deal was the New

Reconstruction, or at least Eleanor Roosevelt tried to infuse her husband’s

administration with progressive politics.

Even

the most popular politicians are unpopular with somebody. A Gal-

lup

poll in 1958 indicated that if respondents had the chance to dine with

three people in history, Eleanor would come in sixth, Franklin second, Jesus

eleventh, and Abraham Lincoln first.

17

On the other hand, anti-Semites in

the country called the Roosevelt administration the “Jew Deal” because of

AMERICAN STORIES

154

the notable Jewish people appointed to high-level positions. Conservative

Democrats and Republicans started to wonder together whether Roosevelt

was turning the nation into a socialist experiment because he promoted close

bonds between government and society, between the feds and the economy.

While the New Deal undoubtedly bonded the federal government more finely

and more firmly to nearly every facet of American life, the argument can

be made that President Roosevelt wanted to save capitalism, not smother it

with bolshevism or socialism. A national health care plan was not enacted,

private property was not confiscated by the government, and unions like the

United Auto Workers (UAW) did not damage the viability of companies like

General Motors or Ford. In fact, by 2007, when Ford Motor Company was

losing more than $2,000 per every car it sold, a leading expense keeping Ford

from being profitable was the pension plan created in the 1940s. However,

that pension plan—which guaranteed health care and monthly checks for life

after retirement—was exactly the plan Walter Reuther, UAW president, did

not want.

Reuther wanted companies to buy health care collectively and to

collectively pool their retirement funds, but major steel and auto companies

resisted, saying that such a plan was “communist” and that their freedom of

choice would disappear into any kind of collective scheme. Today, almost all

U.S. steel and auto companies are struggling, largely under the burden of their

pension plans, which would be less draining had they enacted Reuther’s plan.

Unions wanted capitalism to work. Agreeing, President Roosevelt promoted

certain safeguards—like the Securities and Exchange Commission, which

oversees Wall Street—in order for people to have faith in the system.

While government involvement in the economy has been debated ever

since, no one disagrees that it was World War II, rather than the New Deal,

that lifted the United States out of the Great Depression.

Notes

1. Richard Gid Powers, Secrecy and Power: The Life of J. Edgar Hoover (New

York: Free Press, 1987), 78.

2. J.D. Reed, “The Canvas Is the Night, Once a Visual Vagrant, Neon Has

a Stylish New Glow,” Time, June 10, 1985,

www.time.com/time/magazine/

article/0,9171,958470-2,00.html.

3. Quoted in Martin L. Fausold and George T. Mazuzan, eds., The Hoover Presi-

dency:

A Reappraisal (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1974), 52.

4. Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., The Cycles of American History (New York: Mari-

ner

, 1999), 378.

5. Quoted in Schlesinger, The Cycyles of American History, 378.

6.

Earl Proulx, Yankee Magazine’s Make It Last: Over 1,000 Ingenious Ways to

Extend the Life of Everything You Own (Dublin, NH: Yankee, 1996), 346.

155

INTO THE GREAT DEPRESSION

7. Special to the New York Times. “ESLICK DIES IN HOUSE PLEADING FOR

BONUS: Tennessee Democrat Stricken by Heart Disease in Midst of Impassioned

Speech. TRAGEDY MOVES VETERANS Shack Flags Put at Half-Staff––House Ad-

j

ourns and Will Vote on Patman Bill Today. ESLICK FALLS DEAD PLEADING FOR

BONUS.” New York Times (1857–Current file), June 15, 1932, www.proquest.com/.

8. Quoted in Tom H. Watkins, The Hungry Years: A Narrative History of the Great

Depression in America (New York: Henry Holt, 1999), 138.

9. Quoted in M.J. Heale, Franklin D. Roosevelt: The New Deal and War (New

York: Routledge, 1999), 1.

10. Lewis Copeland, Lawrence W. Lamm, Stephen J. McKenna, eds., The World’s

Greatest Speeches (Mineola, NY: Dover, 1999), 508.

11. “THRONGS ARE CALM AS BRANCHES CLOSE: Thousands Gather

About Doors, but Most Accept Situation Philosophically. 8,000 AT ONE BRONX

OFFICE Men, Women in Crowd––Line Begins Forming at 6 in Morning––Police-

m

en on Guard.” New York Times (1857–Current file), December 12, 1930, www.

proquest.com/.

12. Timothy Egan, The Worst Hard Time (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2006), 8.

13. Donald Worster, Dust Bowl: The Southern Plains in the 1930s (New York:

Oxford University Press, 1982), 54.

14. For a full account of Louis Sanchez’s life, go to Dust Bowl Oral History Project,

Ford County Historical Society: A Kansas Humanities Council Funded Project, August

18, 1998,

www.skyways.org/orgs/fordco/dustbowl/louissanchez.html.

15. Jan Pottker, Sara and Eleanor: The Story of Sara Delano Roosevelt and Her

Daughter-In-Law, Eleanor Roosevelt (New York: St. Martin’s, 2004), 71.

16. Vincent Fitzpatrick, H.L. Mencken (Macon, GA: Mercer University Press,

2004), 77.

17. “Famous People,” The Gallup Poll: Public Opinion, 1935–1971 (New York:

Random, 1972), 2: 1560.

OUT OF THE DEPRESSION AND INTO WAR

9

Out of the Depression

and Into War

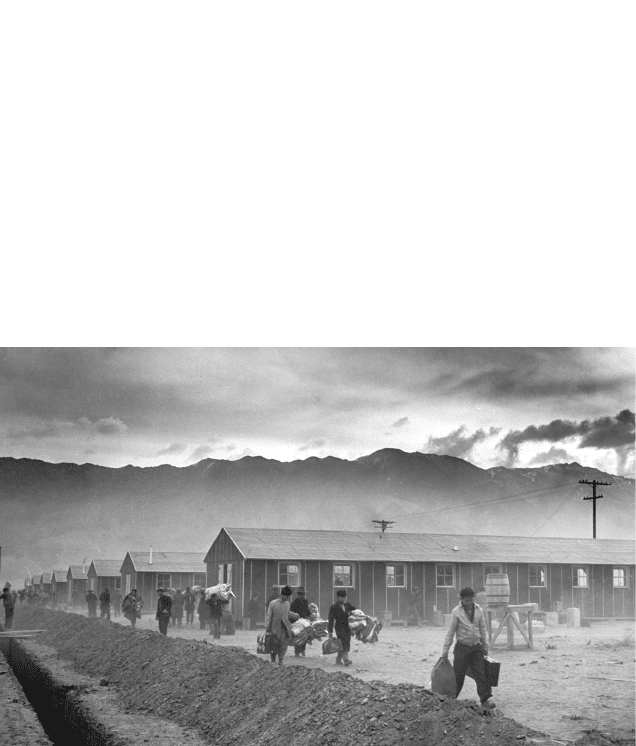

First Japanese-American arrivals at the Manzanar War Relocation Center,

1942. (Eliot Elisofon/Getty Images)

157