Ripper J. American Stories: Living American History. Volume 2: From 1865

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

WORLD WAR I

99

6

World War I

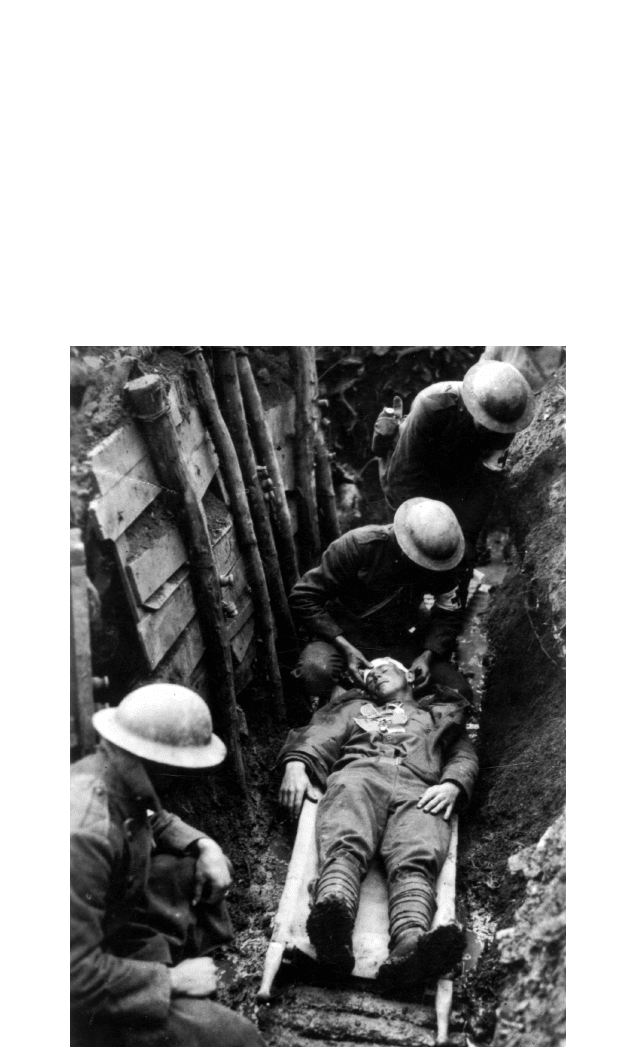

Trench aid. (Sergeant Leon H. Caverly/Getty Images)

AMERICAN STORIES

100

Did Civilization Civilize?

What has been known since the 1940s as World War I, but which was roundly

known at the time as the Great War, made the days of the early 1900s seem

like a drowned dream peopled with fairy children waving from an innocent

place lost in time. Theodore Roosevelt’s own children, giddily known as the

White House Gang, once planned an “attack” on the White House. President

Roosevelt caught wind of their invasion scheme and sent them a note through

the War Department telling them to abort the attack. Within ten years of Roos-

evelt’

s leaving the White House, the War Department was sending messages

about a genuine call to arms after hostilities broke out in Europe in 1914.

W

hile war had always been what William Tecumseh Sherman plainly called

“hell,” the Great War leeched away age-old romantic fantasies about “good”

wars. The romance was poisoned on battlefields where chemical gas attacks

caused men’s lungs to bleed and their skin to pucker, boil, and sometimes burn

down to the bare bleached bone. Young soldiers frightened by wafting green

clouds of chlorine gas choked down their fear and struggled to fit gas masks

over their horse’s heads. The old world and the new crashed into each other

on the bomb-pitted Western Front of France and Belgium as wooden recon-

naissance

airplanes whirred over baggage trains of rickety wagons pulled by

mules and horses. From 1914 through 1918, at least 10 million men died on the

battlefields of Europe, including 115,000 U.S. soldiers—“doughboys”—who

began arriving in mid-1917. France and Germany buried roughly 16 percent

of their male populations, almost one out of every five men.

What led to this waste and ruin of civilization? Why would the wealthiest

nations on the planet—Great Britain, France, and Germany—choose annihi-

lation

rather than continue to promote science, medicine, art, and above all

peace? (Then again, war often prompts fits of invention in science, technol-

ogy

, medicine, and art.) In the nineteenth century, the prospect for a healthier

planet had risen from laboratories like a spring bloom in the midst of a winter

freeze as the dread terror of infections and epidemics slowly receded, chased

away by the application of education, reason, and cooperation. Louis Pasteur

developed the vaccination for rabies in 1880, and European scientists were

busy publishing papers on germ theories of disease. It was becoming common

practice in clinical settings for doctors to wash their hands, one of the biggest

developments ever in medicine, and antiseptics were introduced to hospitals

during the 1870s following the research of Joseph Lister, who trusted Pasteur’s

work and successfully tried carbolic acid as a means of killing bacteria dur-

ing

surgeries. (If, by the way, you rinse with “Listerine,” you have a swish

of Joseph Lister’s name in your mouth.) After the Spanish-American War in

Cuba, an American doctor named Walter Reed (the namesake for the military

101

WORLD WAR I

hospital in Washington, DC) drained swamps to remove mosquito habitat,

finally offering relief from yellow fever, a terrifying virus. This knowledge

allowed U.S. doctors and engineers in Panama in 1904 to complete the canal

where the French had failed twenty years before.

Under

microscopes, the invisible workings of the natural world could be

reduced to their smallest components and then interpreted as elaborate theo-

r

ies, like genetic evolution. France discarded its Catholic-run primary schools

in favor of a secular education system. Understanding would derive from

logic and literature, not from church doctrine. While continentals absorbed

Sigmund Freud’s dream interpretations, Karl Marx’s explanations of the role

of economics in history, and Albert Einstein’s mind-bending dissertations on

light particles and relative reality, art galleries and symphonies flourished.

Pointillist painters re-imagined the pastel romanticism of impressionist gar-

dens

and parasol strolls by the Seine in a dot-by-dot rendering of the world.

Civilization was in full bloom.

W

ith disease on the run, space and time unfolding their secrets, and a

profound movement toward citizen participation in government (throughout

western Europe at least)—with progress an act rather than a mere word—with

what seemed a dawning age of permanent summer and perpetual sunshine,

why did Europeans try to destroy each other?

The Causes of

World War I in Europe

By 1914, Europe was a madhouse. In England, 2,250 “noble” families owned

almost 50 percent of all the farmland, while 1,700 people owned 90 percent

in Scotland. Ten years earlier, Russia had shipped hundreds of thousands of

soldiers across Siberia to fight a colonial war in China, not against the Chinese

but against the Japanese, who also wanted a piece of China. The Russians lost,

and while retreating soldiers starved, one batch of officers chugged home in

lavish railroad cars filled with vodka and prostitutes. (Incidentally, Theodore

Roosevelt orchestrated the peace for the Russo-Japanese War, earning him in

1906 the first Nobel Peace Prize for an American.). Back in Russia, a popular

revolution threatened to overthrow the czar, who responded to democratic

demands by stomping on freedom. The czar’s police and army spied on,

deported, and shot anyone who seemed the least bit uppity—including a few

hundred peasants led by a priest carrying a letter begging the czar for help.

A jog to the west, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany, which had been unified as

a nation only in 1871, preferred military rule to the messiness of democracy,

which became a major problem after 1910 as the Reichstag (parliament) was

taken over one vote at a time by socialists. The kaiser and his spike-helmeted

advisers did not know what to do. In the words of historian D.F. Fleming,

AMERICAN STORIES

102

offering a glimpse into the prewar anxiety of German society, “The nation

created by blood and iron was becoming weary of the weight of iron on its

back and of the load of parasitic militarism on its soul.”

1

A war, as it turned

out, could be just the distraction needed to keep the socialists from promoting

their annoying anti-imperialist notions about fairness and sharing of resources.

War and chaos were regularly one neighboring region away.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire sat to the south of Germany like a cracked

bowl full of mismatched fruit. The unstable arms of the empire’s ruling Haps-

bur

g monarchs stretched out from central Europe to the edge of Turkey. The

Hapsburg family reigned over an ethnic assemblage of Muslims, Catholics,

Jews, Hungarians, Germans, Turks, Croats, and Serbs. These people did

not get along too well, and any number of them wanted their independence,

especially the Serbs of Bosnia-Herzegovina, who had been forcibly dragged

into the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1909. One Serbian revolutionary group

calling itself the Black Hand trained young rebels to shoot and bomb––tactics

today called terrorist––tactics often used then and now for political reasons.

The Black Hand and its small cells of three to five members wanted to find a

way to get out of the Austrian empire and into the Serbian nation right across

the Drina River. Gavril Princip was a disciple of the Black Hand still in his

teens, and on June 28, 1914, he killed Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a member

of the ruling Hapsburg monarchy—in fact, the heir apparent, next in line to

rule. On a goodwill tour occasioned by his wedding anniversary, Ferdinand

was in Sarajevo to inspect military drills. A team of assassins waited, poised

to bomb and shoot him, the weapons having been provided by the Serbian

army. A hand bomb was tossed at his motorcade, but the archduke managed

to deflect it with a raised arm after hearing the strike of metal on metal used

to spark the fuse, and the bomb exploded behind his car, injuring some civil-

ians.

Rather than canceling the rest of his day’s tour, the archduke composed

himself and followed the planned route, landing him directly in front of Princip,

who had just exited a sandwich shop. Princip pulled a pistol from his coat,

walked up to Franz Ferdinand’s car, and fatally shot him. In a continent with

fewer funhouse mirrors, these events might have been followed by a series of

inquiries, trials, and perhaps even limited battles between Austria and Serbia.

But this was the Europe of 1914, blighted by the high ego of its own power

and by the mistaken belief that alliances and treaties could be a guarantee

against war, rather than a cause.

The madhouse afflictions of inequality and strife that left European nations

internally divided were amplified internationally by the entangling alliances

that nearly every country had made. Russia supported the Serbs, and Russia

and France had a mutual defense treaty. So when Austria declared war on

Serbia in late July, Russia responded by mobilizing its forces in preparation

103

WORLD WAR I

for war with Austria-Hungary. (Unfortunately for the Russian peasants, whose

sons made up the bulk of the military and who soon died by the millions,

Russia’s military resources were inadequate and antiquated—not enough

rifles, not enough bullets, not enough winter coats, gaps in the supply lines,

which meant gaps between meals. Plus the generals tended to know as little

about warfare as their dream-headed czar, whose wife had fallen under the

spell of a shaggy charlatan-monk, Rasputin. The Russian bear was enormous,

but its claws needed sharpening.) Germany and Austria-Hungary had mutual

defense treaties also, so Germany declared war on Russia on August 1 and

on France two days later. Great Britain was tied to Belgium, and Japan was

tied to Great Britain. And so on.

By early August 1914, Europe was at war, and the United States was 3,000

miles away, 3,000 happy miles. In Into the Breach, authors Dorothy and

Carl Schneider offer a straightforward appraisal of the war’s causes: “greed,

stupidity, and carelessness among both the Allies [Britain and France] and

the Central Powers [Germany and Austria].” The Schneiders characterize the

careless leaders of these nations as “obstinate, callous, and unimaginative old

men” who sadly directed “soldiers . . . inspired by enthusiasm and a passion-

ate

idealism, marching off to war with flowers in their rifles, decorating their

transports with garlands.”

2

The belligerent old naifs of Europe, borrowing

the deadly optimism of Confederate and Union Americans in 1861, expected

the hostilities to last no longer than weeks or months. Few people could

foresee just how horribly well trenches would work. In the summer of 1914,

America’s leaders seemed neither so careless nor stupid as their European

peers, and its young men were inspired by a different enthusiasm and pas-

sionate idealism—to stay safely out of the way

.

War, Baseball, Ragtime: From August 1914 to January 1917

War is fought for victory, but victory means different things to different par-

t

icipants. It can reasonably be said that few of the warring nations in 1914 had

very clear-cut goals other than the formless desire to maintain honor and find

glory. Germany was not fighting to own all of Europe. Whatever territorial

acquisitions some Germans had in mind (including the borderlands between

Germany and France) were relatively small compared to the grandiose schemes

of a Caesar, Gengis Khan, or, later, Adolf Hitler. Germany was a latecomer to

colonialism, having recently taken its few overseas territories, mainly in the

South Pacific and Africa. Because of this lateness, Germans felt outdone by

the British and French, neither of whom could match Germany’s industrial

output but both of whom ruled vastly more colonies. Germany felt unfairly

contained. This was nationalist jealousy amplified by fear. But the French and

AMERICAN STORIES

104

British had also been thinking about war as they watched Germany grow in

strength. The German nation had been formed after the French decisively lost

during the Franco-Prussian war, 1870–1871. For the French, memories of the

defeat still smarted. The delicate balance of power on the continent was tilting

toward Germany, and that made for frayed nerves elsewhere. By the start of

the war, the second-largest and newest navy on the planet was Germany’s,

second only to Britain’s. Naval supremacy was the aquatic highway of Britain’s

empire, and its ministers worried about German rivalry on the seas. Germany,

however, did not want to tangle with either Great Britain or the United States,

which made the August 1914 invasion of neutral Belgium a horrible idea.

By the beginning of August 1914, most of central and eastern Europe was at

war, at least on paper, the declarations having been made, the armies mobilized.

To the west, Germany wanted to invade France quickly and easily, so Germany

asked tiny Belgium’s permission to march through its territory on the way to

an end-round invasion of France. The border between Germany and France

was heavily defended, but the French had built no barriers between themselves

and Belgium. The Belgians, being neutral, naturally told the Germans no,

and the Germans, being led by medieval Prussian military minds (haughty,

imperious, and self-confident), naturally enough invaded Belgium.

Is it accurate to say that Americans have always rooted for the underdog

(as long as the underdog was not in America)? Upset and favorable to Bel-

gium

is certainly how most people in the United States acted when Germany

declared war on Belgium on August 4. As the New York Times succinctly

put

it on August 5, “Germany is the aggressor.” Coincidentally, Germany’s

Belgian invasion was also the move that brought Britain into the conflict.

Germany’s first major blunder out of two was the invasion of Belgium, not

least because 200,000 Belgian troops fought bravely enough and effectively

enough to buy two weeks for the French and British to prepare a new line

of defense. And now Americans had a reason to dislike Germany, in fact to

blame Germany for the war.

Blaming Germany and wanting to fight against Germany were—for the

most part—separate emotions. Almost 5 million Americans were first-generation

German or Austrian immigrants, and there were millions more who were

second- and third-generation. In 1914, these Austrian- and German-Americans

tended to have strong, positive feelings about their mother country. There

were also nearly 1.5 million first-generation Irish-Americans, and they had

historical reasons to feel bitter toward the British, who had invaded Ireland

500 years earlier and maintained an unappreciated occupation ever since. So

whether in the streets or in the Senate—where Robert La Follette of Wisconsin

expressed his constituents’ German roots in toots for neutrality the whole way

through the war—many hyphenated Americans favored the Central Powers or

105

WORLD WAR I

at least favored neutrality. While most Americans spoke English and recog-

nized English culture as the dominant strain in the United States, there were

millions of citizens and residents who did not want to shoot, stab, or bomb a

German. Besides feelings of national allegiance, many Americans abhorred

war. Pacifism was popular. Philosophers, bakers, newspaper writers, mechan-

ics,

educators, and fathers and mothers waved flags of peace and neutrality

as vigorously as they could, sending a message to the bullet-brained leaders

of Europe and to the elected officials in the States: American boys should not

cross the sea to die in someone else’s war.

Within months of the start of the war, it became obvious to everyone the

world over that death’s twentieth-century angels carried bigger swords. During

August, German armies cut with planned efficiency through the Belgian lines

and into northern France. On August 22, at the Battle of the Frontiers, 27,000

French soldiers died in a single day. The Germans were within thirty miles

of the cafés and bistros of Paris before grinding to a halt. From September 6

to 14, some 2.5 million soldiers fought the first Battle of the Marne. Many of

the troops were inexperienced, fresh from farms or schools; one exception

was the British Expeditionary Force, which though small was composed of

experienced fighters who had honed their skills in colonial wars. In eight

days of fighting, more than 500,000 soldiers died or were wounded (almost as

many as had been killed in the four years of the American Civil War). While

the battle offered clever stories—especially the arrival of 6,000 French troops

delivered to the front in 600 Parisian taxis—the Marne also witnessed greater

cause for shock and sorrow than anyone could have anticipated. The carnage

was dispiriting and frightful. As troops dug trenches and settled uncomfortably

into what would become four years of unmoving trench warfare, the American

peace movement sang its song of sanity, led by women like Jane Addams and

supported often by mothers who feared for their sons’ lives.

Jane Addams—that unswerving hero of the poor, particularly the poor

recently arrived from Germany and other central European countries—had

already stepped out against war in 1898. Her advocacy for peace during the

quick war against Spain had not damaged her reputation. In late 1914, as the

war in Europe fell into a deadly stalemate of mortars and “aeroplane” pilots

firing machine guns, organizations formed to find better means than bullets for

ending the conflict. In February 1915, an international group of women met at

The Hague in the Netherlands and created the Women’s International League

for Peace and Freedom. Jane Addams was there, and she got elected to go on

a tour of Europe to negotiate peace settlements with the warring parties.

Only

three months later, during Addams’s European tour, Germany made

its second tremendous blunder of the war: on May 7, 1915, a U-boat’s torpe-

d

oes sank a British luxury ship, the Lusitania, drowning almost 2,000 people,

AMERICAN STORIES

106

including 128 Americans, in the waves off the coast of Ireland. Babies in

baskets were sucked under the bubbling swirl created by the massive ship’s

descent. Public opinion in the United States veered into angry denunciations

of Germany’s submarine warfare, which had now taken American lives where

the British blockade of Germany’s coast had previously taken only dollars.

President Woodrow Wilson demanded that Germany stop sinking merchant

vessels headed for Britain’s coast. In essence, he called for freedom of the seas

for neutrals, a right insisted on by the United States just over 100 years earlier,

a leading cause of the War of 1812. In Germany, feelings were mixed: the

superior British navy had blockaded the northern coast, making it increasingly

difficult to get needed food and war materials; unrestricted U-boat attacks were

seen as a hope for survival. But the prospect of the American goliath joining

the war was scarier than the prospect of tightening the collective belt. By

early 1916 (after almost a year and two more ship sinkings involving Ameri-

can

casualties), Germany relented and agreed to stop its unrestricted U-boat

warfare. While waiting for Germany to comply, Wilson called for increased

military preparedness, especially for an increase in the size of the navy and

army. Congress agreed reluctantly, providing only token numbers compared

to the millions of uniformed men in Europe at the time.

Jane

Addams protested Wilson’s new approach. On October 29, 1915,

she sent Wilson a letter requesting a different policy than “preparedness.”

Speaking officially for the domestic Women’s Peace Party, she explained,

“We believe in real defense against real dangers, but not in a preposterous

‘preparedness’ against hypothetic dangers.” Germany, in other words, was

not a “real danger” to the United States. Addams and her cohorts feared the

United States would lose the world’s trust by arming itself unnecessarily.

Besides, she said, if Wilson wanted to be known for the “establishment of

permanent peace,” he would need to find ways other than increasing “that

vast burden of armament which has crushed to poverty the peoples of the old

world.”

3

Addams’s pacifism and willingness to address Wilson directly earned

her the esteem and support of Europeans and Americans alike; however, once

America entered the war feelings about Adams would sour. She received a

letter from a Mrs. M. Denkert, a German-American who had emigrated to the

States in the 1880s, who wrote that she was the mother of “two big, healthy

boys” and that her heart was “wrung at the thought of all those mothers not

alone in Germany, but in all the warring countries, who have to send forth

these treasured tokens of God, either never to see them again or else to get

them back crippled or blind or demented.” Denkert pleaded with Addams to

“keep up your brave fight and emperors and kings and ministers and mankind

will bless you for it for all times!”

4

President Wilson agreed with the peace sentiment, but he continued to

107

WORLD WAR I

push for preparedness. Yet during the presidential election campaign in 1916,

Wilson used the slogan “He kept us out of war”—ironic, as it would turn out.

The year of his election propped up the promise of his slogan, as there were

no serious breaches of the peace between Germany and the United States.

Besides, Americans had military worries much closer to home.

Ever since 1910, Mexico had been in a state of revolution, its long-time

dictator Porfirio Díaz soon exiled to France. Díaz was followed by a succes-

sion

of contenders, one of whom—Victoriano Huerta—ordered the arrest of

U.S. sailors who had gone on shore leave in Tampico in 1914. With the sting

of imprisoned U.S. sailors and news of a German shipment of American-

made rifles headed for Huerta’s forces, President Wilson ordered a party

of marines ashore at Veracruz, ostensibly to prevent the rifles from being

unloaded. In the ensuing street fighting, eighteen marines died, and Huerta’s

reputation improved, briefly: he had stood up to the northern giant. Huerta,

however, had competition for the presidency of Mexico, and with the help

of the United States, he was replaced by Venustiano Carranza. Carranza’s

revolutionary credentials, however, were insufficient for other reformers in

the impoverished country who wanted the peasants to have more rights to

own the land they worked. Pancho Villa, a former bandit turned revolution-

ary

general, had been clashing with Carranza’s forces—including a brief,

unpopular occupation of Mexico City. For a time, Villa had received weapons

from the United States and even had a movie contract, which meant some of

his real battles got filmed. However, in an effort to promote stability south of

the border, President Wilson decided to cut off military aid to Villa’s forces.

In response, Villa’s men shot American tourists and, in March 1916, crossed

the border into Columbus, New Mexico, where they set fire to the town and

killed eighteen Americans. This was done under the faulty assumption that

Villa’s reputation would soar—like Huerta’s had—if he clashed with the An-

glos.

Instead, Villa became a villain in the States, hunted now by Carranza’s

forces and by 6,000 men under John J. Pershing. In 1916, the public in the

United States was more eager to punish Villa’s killings of railroad tourists

and his “invasion” of the nation than they were to engage the “Huns,” as the

British propaganda spinners had labeled German troops.

W

hile Pershing and his troops chased the elusive Pancho Villa (whom they

never caught) through northern Mexico, Americans distracted themselves with

various irresistible pastimes. Baseball had a new star, a phenomenon named

George Herman “Babe” Ruth—a stocky man-boy with memories of a hard

childhood and a taste for antics of a peculiarly American stripe.

5

Babe Ruth

joined the (then) minor-league Baltimore Orioles squad in 1914, recruited

directly from a Catholic reform school (as it turned out, a ball-player incu-

bator

, bat and ball being a safe outlet for rambunctious, discarded boys). At