RAND Corporation. Social Science for Counterterrorism

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Organizational Decisionmaking by Terrorist Groups 235

of greatest importance. e choices of groups with complex internal

dynamics or competing internal factions may be dominated by how

they will “play” for internal constituencies. Some groups will be opti-

mizers, seeking to make the best choices possible given their circum-

stances; others will satisfice, seeking what is “good enough” rather than

optimal. Groups will also have different preferences and tolerances for

such factors as operational risk or incomplete information. Although a

given level of information or risk may reach an acceptable threshold for

one organization and it will decide to act, another organization might

instead decide to gather more intelligence or defer a decision until the

risks of acting can be reduced.

Implications for Strategy and Policy

In considering strategies for counterterrorism aimed at the organiza-

tional level, the decisionmaking processes of terrorist groups are one

potential target for action. In general, if options are unavailable to take

on terrorist groups directly, action to complicate or shape their deci-

sionmaking in ways that make it more difficult for them to plan and

stage violent actions can be an alternative. To the extent that the factors

shaping a particular group’s decision processes can be identified and

understood, defensive measures can also be better crafted to frustrate

their operations or guide group choices in ways that are favorable for

defense and security organizations. Clear models, based on available

social-science understandings of terrorist organizational behaviors, can

help to guide such policy design.

In considering terrorist group decisionmaking, and opportuni-

ties for counterterrorism action, there is an existing basis for think-

ing: Efforts at deterrence and influence are, at their most basic,

efforts to shape the choices that groups make about the things they

do and the ways they attempt to do them. From this perspective,

security measures seek to shape group risk tolerance, as do “clas-

sic” attempts at deterrence through threats of punishment or retali-

ation for specific acts; information operations telegraphing how use

of unconventional weapons would be viewed negatively in a group’s

236 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

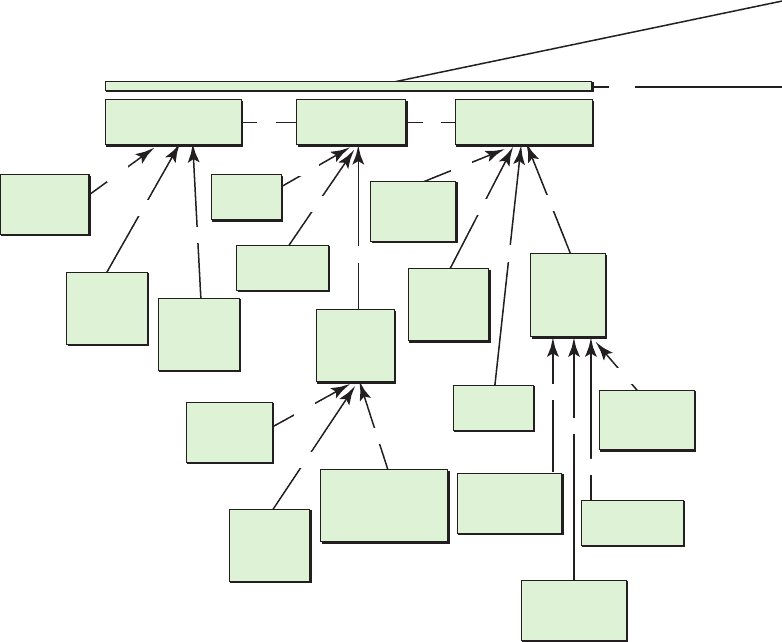

Figure 6.1

Factors Shaping Terrorist Group Decisionmaking

RAND MG849-6.1

Likelihood of

decision to act

Scope of positive reaction

action will produce in

relevant population

Legitimacy and

acceptability of

target, means,

action, etc.

Consistency

with group

ideology

Level of

pressure to act

imposed by

competing

groups

Level of

pressure to act

imposed by

external events

or demands

Consistency with

group goals/

interests

Consistency

with

preferences of

state sponsors

Level of

alignment of

action with

any external

influences

Consistency with

preferences of strategic

or operational

influences in networks

or movements

Consistency

with

preferences of

cooperating

groups

Permissiveness

of group

success criteria

Defenses at

desired

targets

Group OPSEC

effectiveness

Scope of group

dynamics that

skew preferences

(e.g., groupthink)

Effect of past

behavior bias on

future preferences

Effects of

clandestinity on

group activities

Effectiveness

of state CT

activities

Group

capability

level

Level of

member risk

tolerance

Biasing effect

of recent

experience

(positive and

negative)

Group risk

tolerance

Group effects

on risk

decisions

Availability

of resources

from others

Amount of time

for planning,

prep and

implementation

Amount of

situational

awareness

information

available

to group

Amount of

technical

knowledge

available

to group

Access to

external

knowledge

sources

Insulation of group

from pressure

(e.g., safe haven)

Amount of money

available to group

Amount of

technology available

to group

(e.g., weapons)

Number of

appropriate

people in

group

Ability to

gather new

information

Breadth and

depth of

internal

“knowledge

stocks”

Legitimacy and

acceptability of

target, means,

action, etc.

Perceived

intensity of

need to act to

preserve group

cohesion

Level of “bias

to action”

within group

Intensity of

idiosyncratic

preferences

toward

particular

activity

Intensity of

idiosyncratic

preferences among

leadership

Intensity of

idiosyncratic

preferences among

membership

Forestalling a negative

event an included case of

a perceived positive

outcome?

Group perceptions

of other elements

that shape public

support for

terrorist activity

t5BSHFUFEHPWFSONFOU

t(FOFSBMQPQVMBUJPO

t4VQQPSUQPQVMBUJPO

Decisionmaker beliefs about:

and and

and

or or

(+/–)

(+/–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

Amount action will

advance group

strategy or interests

Scope of positive reaction

action will generate

inside group

Amount and

quality of group

communications

capability (to get

information to

decisionmaker)

Acceptability of

risks associated

with action

Level of resources

group is willing to

commit to action

Perceived sufficiency

of information to

make decision

Level of

“knowledge

threshold”

demanded

for decision

(+)

(–)

Organizational Decisionmaking by Terrorist Groups 237

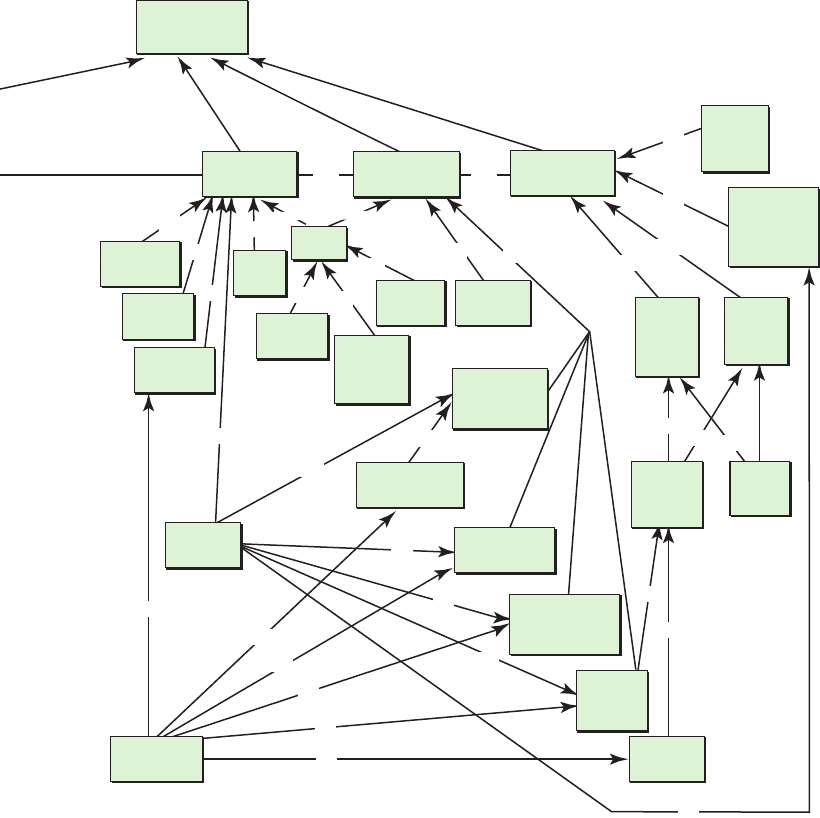

Figure 6.1

Factors Shaping Terrorist Group Decisionmaking

RAND MG849-6.1

Likelihood of

decision to act

Scope of positive reaction

action will produce in

relevant population

Legitimacy and

acceptability of

target, means,

action, etc.

Consistency

with group

ideology

Level of

pressure to act

imposed by

competing

groups

Level of

pressure to act

imposed by

external events

or demands

Consistency with

group goals/

interests

Consistency

with

preferences of

state sponsors

Level of

alignment of

action with

any external

influences

Consistency with

preferences of strategic

or operational

influences in networks

or movements

Consistency

with

preferences of

cooperating

groups

Permissiveness

of group

success criteria

Defenses at

desired

targets

Group OPSEC

effectiveness

Scope of group

dynamics that

skew preferences

(e.g., groupthink)

Effect of past

behavior bias on

future preferences

Effects of

clandestinity on

group activities

Effectiveness

of state CT

activities

Group

capability

level

Level of

member risk

tolerance

Biasing effect

of recent

experience

(positive and

negative)

Group risk

tolerance

Group effects

on risk

decisions

Availability

of resources

from others

Amount of time

for planning,

prep and

implementation

Amount of

situational

awareness

information

available

to group

Amount of

technical

knowledge

available

to group

Access to

external

knowledge

sources

Insulation of group

from pressure

(e.g., safe haven)

Amount of money

available to group

Amount of

technology available

to group

(e.g., weapons)

Number of

appropriate

people in

group

Ability to

gather new

information

Breadth and

depth of

internal

“knowledge

stocks”

Legitimacy and

acceptability of

target, means,

action, etc.

Perceived

intensity of

need to act to

preserve group

cohesion

Level of “bias

to action”

within group

Intensity of

idiosyncratic

preferences

toward

particular

activity

Intensity of

idiosyncratic

preferences among

leadership

Intensity of

idiosyncratic

preferences among

membership

Forestalling a negative

event an included case of

a perceived positive

outcome?

Group perceptions

of other elements

that shape public

support for

terrorist activity

t5BSHFUFEHPWFSONFOU

t(FOFSBMQPQVMBUJPO

t4VQQPSUQPQVMBUJPO

Decisionmaker beliefs about:

and and

and

or or

(+/–)

(+/–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(–)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

(+)

Amount action will

advance group

strategy or interests

Scope of positive reaction

action will generate

inside group

Amount and

quality of group

communications

capability (to get

information to

decisionmaker)

Acceptability of

risks associated

with action

Level of resources

group is willing to

commit to action

Perceived sufficiency

of information to

make decision

Level of

“knowledge

threshold”

demanded

for decision

(+)

(–)

238 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

sympathizer community or by the international community seek to

shape a variety of different elements of decisionmaking and also the

apparent value of pursing them; diplomatic efforts to end state spon-

sorship seek to constrain group resources and reduce the chance that

the group will be willing to devote enough people and technology to

operations of concern; and so on.

72

Drawing on current social-science literature and other available

data on group decisionmaking, the model represented in Figure 6.1

captures the range of elements that shape group choices, from what

those choices are intended to accomplish to the risk and information

thresholds a group may impose on its on decisions. In framing these

factors, some elements go back through decades of terrorism research

and are supported by broad bodies of knowledge in related fields. For

example, the influence of organizational dynamics on decisionmak-

ing has been recognized for many years, has been examined in a vari-

ety of terrorist organizations, and—given the much broader interest

in how all groups make choices—has been examined in a variety of

other types of organizations as well. Others factors are more provi-

sional, being based on smaller amounts of data or less direct study

of the behavior in terrorist groups. An example of this latter class is

questions about the effect of organizational risk tolerance on group

decisionmaking. Although there are enough data to make a case that

it is an important factor that needs to be considered and included, it

has not itself been systematically studied. As a result, in some cases,

concepts are framed just as they are in literature sources and my model

summarizes those concepts in a uniform structure; in others, I have

crafted categories to bring together separate (and sometimes still thin)

strands of thought that have not yet been fully explored or placed into

a useful framework.

When considering application of this model to guide thinking

about strategy and policy, some caveats are appropriate. First, for sim-

plicity the model is framed as a group considering a single choice, with

the factors shaping the likelihood of making a decision. In reality, deci-

sionmakers generally consider multiple options and make comparisons

among them—even if only to compare the consequences of an action

against the consequences of taking no action at all. As a result, the

Organizational Decisionmaking by Terrorist Groups 239

additional complication of making those comparisons among options,

and the effect of which options groups choose to weigh against each

other, is a factor that I have not considered explicitly.

Second, although understanding the factors that shape group

choices can make it possible to make more informed projections about

what groups may or may not do, real limits constrain the ability to

do so. ere are limits on the intelligence that is available about inter-

nal group deliberations. As a result, just as the terrorist group deci-

sionmaker will invariably have limits on available data, so too will the

policymaker or operator in counterterrorism.

ird, even a systematic and deliberative terrorist group that makes

the best decision it can at a given time can simply be wrong, meaning

that even with an excellent model that captures and integrates all avail-

able information on how choices are made, it may still not be possible

to predict the group’s future behavior. To be rational does not mean

to be perfect. A variety of elements can affect the quality of a group’s

choices, including divergence between what the group thinks and what

“truly is” (for example, a group’s assumptions about how its actions will

be interpreted by their target audiences). A group can similarly have

misperceptions about its own levels of skills or knowledge that can

lead to miscalculation and error (Drake, 1998). Incorrect knowledge,

bad situational awareness, too little information, or too much data to

assess in the time available to the decisionmakers can similarly degrade

the quality of an organization’s choices.

73

e situation the group faces

may also simply change, making choices that might have been benefi-

cial in one environment detrimental under new circumstances. As with

all groups, terrorist organizations have bounds on their understanding

and knowledge that make it difficult to project their own actions into

the future and understand their consequences with certainty.

Fourth, although many analyses approach terrorist groups as

“single decisionmakers,” the reality is that they (and all organizations)

are made up of individuals whose interests may or may not be entirely

congruent with those of the group as a whole. Individual actors “look-

ing out for themselves” can therefore inject different sets of preferences

into a decision process. Some authors have framed this as a principal-

agent problem given that central terrorist actors have difficulty con-

240 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

trolling what other members do, thus opening the opportunity for

self interested behavior (Chai, 1993; Shapiro, 2005a). Such individual

behaviors also arise as a result of rivalry within groups and contests for

power or resources.

74

Finally, although a group may make “the right choice” to advance

its interests in a specific situation, it is not certain that it will actually be

able to implement its decisions. Some of the same factors that were dis-

cussed above—such as command and control issues,

75

organizational

structure constraints, security concerns limiting communication, and

the bringing together of resources—can also get in the way of a group’s

ability to translate thought into action.

As a result, even armed with the best that social-science research

currently has to offer, the task of understanding terrorist group deci-

sionmaking and anticipating group behavior must be approached with

humility. In doing so, the analyst (and a decisionmaker relying on the

analysis) must know something of the nature of the group itself. Exam-

ination must focus on the appropriate decisionmaking units within

an organization, where the results of social-science research on group

behavior are applicable, and should not assume that identical processes

apply in groups as vastly different as individual terrorist cells and loosely

coupled collections of individuals linked only by a common ideology.

Although both the interplay of ideas and the deliberative processes that

occur at all points on the spectrum of terrorist organizational behavior

are important, variations in the processes in different types of organiza-

tions must be understood and taken into account.

e fact that decisionmaking and the factors that shape it are

inherently idiosyncratic in individual terrorist groups means that gen-

eral models that can predict “terrorist behavior” will be elusive at best.

However, at the same time, even if models may not be predictive,

laying out the range of factors that shape terrorist group decisions can

still aid in understanding how groups of interest might behave and can

guide counterterrorist thinking. In examining a specific group and the

factors that are most important given the available information on its

leadership, membership, and environment, such models can help to

assess the possible effects of different strategies for deterrence or influ-

Organizational Decisionmaking by Terrorist Groups 241

ence and to prioritize those likely to be more or less likely to be effec-

tive against it.

Bibliography

Ahmed, Fazal, Terrorism as a Rational Tactic: An International Study, Ann Arbor,

Mich.: University of Michigan, 1998.

Al-Zawahiri, Ayman, letter to Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi, July, 9, 2005. As of January

5, 2008:

http://www.globalsecurity.org/security/library/report/2005/zawahiri-zarqawi-

letter_9jul2005.htm

Anderton, Charles, and John Carter, “On Rational Choice eory and the Study

of Terrorism,” Defence and Peace Economics, Vol. 16, No. 4, 2005, pp. 275–282.

Arquilla, John, and David F. Ronfeldt, “e Advent of Netwar: Analytic

Background,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 22, No. 3, 1999, pp. 193–206.

———, eds., Networks and Netwars: e Future of Terror, Crime, and Militancy,

Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2001. As of January 5, 2009:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1382/

Atran, Scott, and Marc Sageman, “Connecting the Dots,” Bulletin of the Atomic

Scientists, Vol. 62, No. 4, 2006, p. 68.

Atwan, Abdel Bari, e Secret History of al Qaeda, Berkeley, Calif.: University of

California Press, 2006.

Berrebi, Claude, and Darius Lakdawalla, “How Does Terrorism Risk Vary Across

Space and Time? An Analysis Based on the Israeli Experience,” Defence and Peace

Economics, Vol. 18, No. 2, 2007, pp. 113–131.

Bloom, Mia, Dying to Kill: the Allure of Suicide Terror, New York: Columbia

University Press, 2007.

Bueno de Mesquita, Ethan, and Eric S. Dickson, “e Propaganda of the Deed:

Terrorism, Counterterrorism, and Mobilization,” American Journal of Political

Science, Vol. 51, No. 2, 2007, pp. 364–381.

Calle, Luis de la, and Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca, “e Production of Terrorist

Violence: Analyzing Target Selection in the IRA and ETA,” unpublished, 2007.

Carley, Kathleen M., “Organizational Learning and Personnel Turnover,”

Organization Science, Vol. 3, No. 1, 1992, pp. 20–46.

Carley, Kathleen M., and David M. Svoboda, “Modeling Organizational

Adaptation as a Simulated Annealing Process,” Sociological Methods & Research,

Vol. 25, No. 1, 1996, pp. 138–168.

242 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

Carter, Josh, “Transcending the Nuclear Framework: Deterrence and Compellence

as Counter-Terrorism Strategies,” Low Intensity Conflict and Law Enforcement, Vol.

10, No. 2, Summer 2001, pp. 84–102.

Casebeer, William, and Troy omas, “Deterring Violent Non-State Actors in

the New Millennium,” Strategic Insights, Vol. 1, No. 10, December 2002. As of

January 5, 2009:

http://www.ccc.nps.navy.mil/si/dec02/terrorism2.asp

Chai, Sun-Ki, “An Organizational Economics eory of Antigovernment

Violence,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 26, No. 1, 1993, pp. 99–110.

Combating Terrorism Center, Harmony and Disharmony: Exploiting al-Qa’ida’s

Organizational Vulnerabilities, West Point, N.Y.: U.S. Military Academy, 2006.

Connor, Robert, Defeating the Modern Asymmetric reat, Monterey, Calif.: Naval

Postgraduate School, 2002.

Cragin, Kim, and Sara A. Daly, e Dynamic Terrorist reat: An Assessment of

Group Motivations and Capabilities in a Changing World, Santa Monica, Calif.:

RAND Corporation, 2004. As of January 5, 2009:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1782/

Crelinsten, Ronald D., “e Internal Dynamics of the FLQ During the October

Crisis of 1970,” in David C. Rapoport, ed., Inside Terrorist Organizations, New

York: Columbia University Press, 1988, pp. 59–89.

Crenshaw [Hutchinson], Martha, “e Concept of Revolutionary Terrorism,” e

Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 16, No. 3, September 1972, pp. 383–396.

Crenshaw, Martha “e Causes of Terrorism,” Comparative Politics, Vol. 13, No.

4, July 1981, pp. 379–399.

———, “An Organizational Approach to the Analysis of Political Terrorism,”

Orbis, Vol. 29, No. 3, Fall 1985, pp. 465–489.

———, “e Psychology of Political Terrorism,” in Margaret G. Hermann,

ed., Political Psychology, San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1986, pp.

379–413.

———, “e Logic of Terrorism: Terrorist Behavior as a Product of Strategic

Choice,” in Walter Reich, ed., Origins of Terrorism: Psychologies, Ideologies,

eologies, States of Mind, Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International

Center for Scholars, 1990, pp. 7–24.

———, ed., Terrorism in Context, University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State

University Press, 1995.

———, “e Psychology of Terrorism: An Agenda for the 21st Century,” Political

Psychology, Vol. 21, No. 2, 2000, pp. 405–420.

Organizational Decisionmaking by Terrorist Groups 243

———, “eories of Terrorism: Instrumental and Organizational Approaches,”

in David C. Rapoport, ed., Inside Terrorist Organizations, London: Frank Cass,

2001, pp. 13–31.

Davis, Paul K., and John Arquilla, inking About Opponent Behavior in Crisis and

Conflict: A Generic Model for Analysis and Group Discussion, Santa Monica, Calif.:

RAND Corporation, 1991. As of July 14, 2008:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/notes/N3322/

Davis, Paul K., and Brian Michael Jenkins, Deterrence & Influence in

Counterterrorism: A Component in the War on Al Qaeda, Santa Monica, Calif.:

RAND Corporation, 2002. As of July 14, 2008:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/monograph_reports/MR1619/

Decker, Warren, and Daniel Rainey, “Terrorism as Communication,” paper

presented at the annual meeting of the Speech Communication Association, New

York, November 13–16, 1980. As of February 25, 2009:

http://eric.ed.gov/ERICDocs/data/ericdocs2sql/content_storage_

01/0000019b/80/35/f1/0b.pdf

Della Porta, Donatella, “Left-Wing Terrorism in Italy,” in Martha Crenshaw, ed.,

Terrorism in Context, University Park, Pa.: Pennsylvania State University Press,

1995, pp. 160–210.

Dingley, James, “e Bombing of Omagh, 15 August 1998: e Bombers,

eir Tactics, Strategy, and Purpose Behind the Incident,” Studies in Conflict &

Terrorism, Vol. 24, 2001, pp. 451–465.

Dolnik, Adam, and Anjali Bhattacharjee, “Hamas: Suicide Bombings, Rockets,

or WMD?” Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 14, No. 3, Autumn 2002, pp.

109–128.

Don, Bruce W., David R. Frelinger, Scott Gerwehr, Eric Landree, and Brian

A. Jackson, Network Technologies for Networked Terrorists: Assessing the Value of

Information and Communications Technologies to Modern Terrorist Organizations,

Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2007. As of July 14, 2008:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR454/

Drake, C. J. M., “e Role of Ideology in Terrorists’ Target Selection,” Terrorism

and Political Violence, Vol. 5, No. 4, 1993, pp. 253–265.

———, Terrorists’ Target Selection, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

Drakos, Konstantinos, “e Size of Under-Reporting Bias in Recorded

Transnational Terrorist Activity,” J.R. Statist. Soc A, Vol. 170, No. 4, October 1,

2007, pp. 909–921.

Drakos, Konstantinos, and Andreas Gofas, “e Devil You Know But Are Afraid

to Face: Underreporting Bias and Its Distorting Effects on the Study of Terrorism,”

Journal of Conflict Resolution, Vol. 50, No. 5, October 1, 2006, pp. 714–735.

244 Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together

Dugan, Laura, Gary Lafree, and Alex R. Piquero, “Testing a Rational Choice

Model of Airline Hijackings,” Criminology, Vol. 43, No. 4, 2005, pp. 1031–1065.

Fleming, Marie, “Propaganda by the Deed: Terrorism and Anarchist eory in

Late Nineteenth-Century Europe,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 4, No.

1–4, 1980, pp. 1–23.

Gerges, Fawaz A., e Far Enemy: Why Jihad Went Global, New York: Cambridge

University Press, 2005.

Gurr, Ted Robert, “Terrorism in Democracies: Its Social and Political Bases,” in

Walter Reich, ed., Origins of Terrorism: Psychologies, Ideologies, eologies, States

of Mind, Washington, D.C.: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars,

1990, pp. 86–102.

Gvineria, Gaga, “How Does Terrorism End?” in Paul K. Davis and Kim Cragin,

eds., Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces Together, Santa Monica,

Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2009. As of January 17, 2009:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG849/

Hayden, Nancy Kay, Terrifying Landscapes: A Study of Scientific Research into

Understanding Motivations of Non-State Actors to Acquire and/or Use Weapons of

Mass Destruction, Fort Belvoir, Va.: Defense reat Reduction Agency, 2007.

Helmus, Todd C., “Why and How Some People Become Terrorists,” in Paul K.

Davis and Kim Cragin, eds., Social Science for Counterterrorism: Putting the Pieces

Together, Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND Corporation, 2009. As of January 17,

2009:

http://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG849/

Hoffman, Aaron, “Taking Credit for eir Work: When Groups Announce

Responsibility for Acts of Terror, 1968–1977,” paper presented at the annual

meeting of the International Studies Association, Montreal, Quebec, March 17,

2004.

Hoffman, Bruce, “e Modern Terrorist Mindset: Tactics, Targets and

Technologies,” Center for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence, St.

Andrews. University, Scotland, October 1997. As of February 25, 2009:

http://www.ciaonet.org/wps/hob03/

———, “e Myth of Grass-Roots Terrorism: Why Osama bin Laden Still

Matters,” Foreign Affairs, May/June, 2008.

Hoffman, Bruce, and Gordon McCormick, “Terrorism, Signaling, and Suicide

Attack,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, Vol. 27, No. 4, 2004, pp. 243–281.

Homeland Security Institute, Underlying Reasons for Success and Failure of Terrorist

Attacks: Selected Case Studies, Washington, D.C., 2007.

Horgan, John and Max Taylor, “e Provisional Irish Republican Army: Command

and Functional Structure,” Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol. 9, No. 3, 1997.