Pumping Station Desing - Second Edition by Robert L. Sanks, George Tchobahoglous, Garr M. Jones

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

JOSEPH

K.

JACKSON

Vice President, Sales

Yeomans

Chicago

Corporation

Melrose Park, Illinois

CHARLES

J.

JECKELL,

PE

Utility

Engineering Administrator

Department

of

Public Utilities

City

of

Virginia Beach, Virginia

CASEYJONES

Manager

Application Engineering

Square

D

Company

Columbia, South Carolina

*GARR

M.

JONES,

BSCE,

BSIE,

PE

Senior Vice President, Design

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut

Creek, California

*GEORGE

JORGENSEN,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Chief Engineer

Salt Lake City Public Utilities

Salt Lake City, Utah

WILLARD

O.

KEIGHTLEY,

PhD

Professor Emeritus

Montana State University

Bozeman,

Montana

RONALD

P.

KETTLE

Superintendent

of

Desert Operations

Los

Angeles County Sanitation Districts

Whittier, California

WILLIAM

R.

KIRKPATRICK,

MSCE,

PE

Project Manager

Engineering-Science

Berkeley, California

*FRANK

KLEIN,

BSAE,

MSCE,

Architect,

PE

(retired)

Formerly,

President

Klein

and

Hoffman,

Inc.

Chicago, Illinois

JOSEPH

R.

KROON,

MSCE,

PE

Director, Liquid Services

Stoner Associates, Inc.

Carlisle, Pennsylvania

MELVIN

P.

LANDIS,

PE

Consulting

Engineer

Carmichael,

California

LONNIE

LANGE

Maintenance Manager

Wastewater

Operations

Division

of

Public Works

and

Engineering Department

City

of

Houston

Houston,

Texas

R.

RUSSELL

LANGTEAU

(retired)

Formerly, Pump Specialist

Black

&

Veatch, Consulting Engineers

Kansas

City, Missouri

*PAULC.

LEACH,

PE

Consulting

Engineer

LaConner,

Washington

Formerly, Chief Electrical Engineer

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

JOHN

LEAK,

BSc,

ARCS

Instrumentation

&

Automation Engineer

Greeley

and

Hansen Engineers

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

JOSEPH

E.

LESCOVICH

Chief

Engineer

GA

Industries

Cranberry Township, Pennsylvania

*JERRY

G.

LILLY,

MS, PE

President

JGL

Acoustics, Inc.

Bellevue, Washington

RICHARD

R.

MALESICH

Generator Sales Manager

A&I

Distributors

Billings,

Montana

RALPH

E.

MARQUISS,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Partner

Rummel, Klepper

&

Kahl,

Consulting Engineers

Baltimore, Maryland

*WILLIAM

D.

MARSCHER

President

Mechanical Solutions

Parsippany,

New

Jersey

COLIN

MARTIN

President

Cham Engineering

Columbia, Connecticut

and

Consultant

to ABS

Pumps, Inc.

Meriden, Connecticut

RHYS

M.

MCDONALD

Senior Scientist

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut Creek, California

M.

STEVE

MERRILL,

PhD,

PE

Project Manager

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Seattle, Washington

WARREN

H.

MESLOH,

PE

Director

Process

Design

&

Equipment Selection

Wilson

&

Company, Engineers

&

Architects

Salina,

Kansas

J.

DAVIS

MILLER,

PE

President

White Rock Engineering, Inc.

Dallas, Texas

STEPHEN

G.

MILLER

(transferred)

Formerly, Vice President

Komline-Sanderson

Peapack,

New

Jersey

ALOYSIUS

M.

MOCEK,

JR.,

PE

Vice President

of

Engineering

Parrish

Power Products, Inc.

Toledo, Ohio

JAMES

L.

MOHART,

MSCE,

PE, CVS

Director

of

Administrative Services

Black

&

Veatch, Consulting Engineers

Kansas City, Missouri

*CHARLES

D.

MORRIS,

PhD,

PE

Associate Professor

of

Civil Engineering

University

of

Missouri

Rolla,

Missouri

Formerly, Principal Engineer

Camp Dresser

&

McKee, Inc.

Boston, Massachusetts

MICHAEL

C.

MULBARGER,

MS, PE

(retired)

Formerly, Vice President

Havens

and

Emerson, Inc.

Cleveland, Ohio

RICHARD

L.

NAILEN,

PE

Project Engineer

Wisconsin Electric Power Company

Milwaukee,

Wisconsin

TIMOTHY

NANCE

Senior Engineer Specialist

Square

D

Company

Columbia, South Carolina

DENNIS

R.

NEUMAN

Research Chemist

Montana State University

Bozeman, Montana

*DONALD

NEWTON,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Partner

Greeley

and

Hansen Engineers

Chicago, Illinois

LORAN

D.

NOVACHEK

Applications Engineer

Waukesha Engine Division

Dresser Industries, Inc.

Waukesha, Wisconsin

ALAN

W.

O'BRIEN,

PE

O'Brien

&

Associates

Albuquerque,

New

Mexico

MICHAEL

R.

OLSON

Senior Applications Engineer

Eaton Corporation, Electric Drives Division

Kenosha,

Wisconsin

STEPHEN

H.

PALAC

Partner

and

Chief Electrical Engineer

Greeley

and

Hansen Engineers

Chicago,

Illinois

CONSTANTlNE

PAPADAKIS,

PhD,

PE

President

Drexel University

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

*RANDALL

R.

PARKS

Principal

Integra Engineering

Denver, Colorado

EVANS

W.

PASCHAL,

PhD

Consultant

Whistler Radio Services

Sinclair Island

Anacortes,

Washington

NEDW.

PASCHKE

Director

of

Engineering

Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District

Madison,

Wisconsin

M.

LEROY

PATTERSON

Manager

Electric

Transmission Operations

Montana Power

Co.

Butte, Montana

ALLAN

W.

PETERSON,

MSc,

PEng

Professor Emeritus

Department

of

Civil Engineering

University

of

Alberta

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

ROBERT

E.

PHILLIPS,

PhD

(retired)

Formerly, Vice President

of

Applications

and

Sales

Turner Designs

Sunnyvale,

California

WYETT

C.

PLAYFORD,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Project Engineer

Williams

&

Works, Inc.

Grand Rapids, Wisconsin

JERRY

P.

POLLOCK

Engineering Manager

Johnson Power Ltd.

Toledo, Ohio

E.

O.

POTTHOFF,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Application Engineer

General Electric

Co.

Schenectady,

New

York

*MARC

T.

PRITCHARD

Manager, Planning

and

Control

Construction Management Division

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut

Creek, California

RICHARD

E.

PUSTORINO,

PE

President

R.

E.

Pustonno,

PC

Commack,

New

York

EDGARDOQUIROZ

Engineer

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut

Creek, California

SANJAY

P.

REDDY

Project Engineer

Carollo

Engineers

Phoenix, Arizona

JOHN

REDNER

Sewerage System Superintendent

Los

Angeles County Sanitation Districts

Whittier, California

DAVID

M.

REESER,

PE

Environmental

Process

Manager

RUST International Corp.

Portland, Oregon

CARL

W.

REH,

PE

(deceased)

Formerly, Partner

Greeley

and

Hansen Engineers

Chicago,

Illinois

WILLIAM

H.

RICHARDSON,

PE

Partner

Alvord, Burdick

and

Howson

Chicago, Illinois

*RICHARDJ.

RINGWOOD,

PE

Consulting Engineer

Walnut

Creek,

California

Formerly, Manager

of

Environmental Engineering

Kaiser Engineers, Inc.

Oakland, California

RONALD

ROSIE

Capital

Projects Administrator

Seattle Metro

(now

King County Department

of

Metropolitan Services)

Seattle, Washington

*ROBERT

L.

SANKS,

PhD,

PE

Consulting Engineer

and

Professor Emeritus

Montana State University

Bozeman,

Montana

*PERRY

L.

SCHAFER

Vice

President

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Oakland, California

JAMES

W.

SCHETTLER

Senior Project Manager, Mechanical

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut

Creek, California

*MARV!N

DAN

SCHMIDT,

PE

Principal Engineer

Boyle

Engineering Corporation

Bakersfield,

California

ARNOLD

R.

SDANO

Vice

President, Engineering

Fairbanks Morse Pump Corporation

Kansas

City, Kansas

DANIEL

L.

SHAFFER,

PhD

Associate Professor

of

Chemical Engineering

Montana

State

University

Bozeman,

Montana

RICHARD

N.

SKEEHAN,

PE

Chief Electrical

Engineer

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut

Creek, California

W.

STEPHEN SHENK,

PE

Manager

of

Civil Engineering

Wiley

and

Wilson,

Architects-Engineers-Planners

Lynchburg, Virginia

*LOWELL

G.

SLOAN

Chief Engineer

Prosser/ENPO

Industries, Inc.

Piqua, Ohio

*EARLE

C.

SMITH

(deceased)

Formerly, President

B.C.

Smith

and

Associates

Upper Montclair,

New

Jersey

LARRY

R.

SMITH,

PE

Civil Engineering Associate

Camp Dresser

&

McKee, Inc.

Dallas, Texas

ROBERT

E.

STARKE

Operations Engineer

Aurora/Layne

&

Bowler

North Aurora, Illinois

OTTOSTEIN

7

PhD

Associate Professor

of

Civil Engineering

Montana

State University

Bozeman, Montana

JOSEPH

W.

STEINER

Plants Superintendent

Public Utilities

City

of

Billings, Montana

DALE

STILLER

Director

of

Maintenance

Madison Metro Sewerage District

Madison,

Wisconsin

BRIAN

G.

STONE,

PE

Consulting Engineer

Cottesloe,

WA,

Australia

Formerly, Vice

President

James

M.

Montgomery Consulting Engineers

Pasadena, California

*SAM

V.

SUIGUSSAAR,

PE

Senior

Engineer

Greeley

and

Hansen Engineers

Chicago, Illinois

CHARLES

E.

SWEENEY,

PE

Partner

Water

Resources

ENSR

Consulting

and

Engineering

Redmond, Washington

JAMESTAUBE

Electrical Designer

Florida Keys Aqueduct Authority

Florida

City,

Florida

HARVEY

W.

TAYLOR,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Vice President

CRS

Engineers

Portland, Oregon

*LEROY

R.

TAYLOR,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Division Manager

CH2M-Hill

Boise, Idaho

WILLIAM

R.

TAYLOR,

PhD,

PE

Professor

of

Industrial

and

Management Engineering

Montana State University

Bozeman, Montana

*GEORGE

TCHOBANOGLOUS,

PhD,

PE

Consulting

Engineer

and

Professor Emeritus

of

Civil Engineering

University

of

California, Davis

Davis,

California

*MICHAEL

G.

THALHAMER,

PE

Manager

and

Director

of

Water

and

Wastewater Engineering

Psomas

and

Associates

Sacramento, California

TIMOTHY

A.

THOR

Architect

KMD

Architects

and

Planners

Portland, Oregon

PATRICIAA.

TRACER,

WBE,

PE

President

TRH

Engineering

Chicago, Illinois

JERALD

D.

UNDERWOOD,

PE

Public Utilities Director

City

of

Billings, Montana

R.

DANIEL

VANLUCHENE,

PhD,

PE

Associate Professor

of

Civil Engineering

Montana State University

Bozeman, Montana

ASHOK

VARMA, MSME,

PE

Vice

President

and

Office

Manager

Camp Dresser

&

McKee, Inc.

Dallas, Texas

LELAND

J.

WALKER,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Chairman, Board

of

Directors

Northern Testing Laboratories, Inc.

(now

Maxim Technologies, Inc.)

Great Falls, Montana

DAVIDWALRATH,

PE

Vice

President

Hazen

&

Sawyer,

PC

New

York,

New

York

THOMAS

M.

WALSKI,

PhD,

PE

Professor

Wilkes University

Wilkes-Barre,

Pennsylvania

HORTON

WASSERMAN,

PE

Senior Project Engineer

Malcolm

Pirnie,

Inc.

White Plains,

New

York

GARYZ.

WATTERS,

PhD,

PE

Dean, College

of

Engineering, Computer Science

and

Technology

California

State University

Chico, California

*THEODORE

B.

WHITON

Formerly, Project Manager

G.

S.

Dodson

&

Associates

Walnut

Creek, California

THOMAS

O.

WILLIAMS

Technical Consultant

on Gas

Engines

and

Power Generation

Engine Products Division

Caterpillar, Inc.

Mossville,

Illinois

ROY E.

WILSON,

PE

President

Wilson Management Associates, Inc.

Glen Head,

New

York

ERIC

L.

WINCHESTER, PEng

Senior Engineer

ADI

Limited

Fredericton,

New

Brunswick, Canada

FREDERICKR.

L.

WISE,

JR.

Vice President

Parco

Engineering

Medfield,

Massachusetts

JOHN

E.

WISKUS, MSSE,

PE

Project Manager

CH2M-Hill

Boise, Idaho

FRANK

A.

WOODBURY,

PE

(retired)

Formerly, Senior Applications Engineer

Westinghouse Electric Corporation

Dallas, Texas

JAMES

R.

WRIGHT,

PE

Senior Project Manager

Black

&

Veatch

Engineers-Architects

Kansas City, Missouri

EUGENE

K.

YAREMKO,

PEng

Principal

Northwest Hydraulic Consultants, Ltd.

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

WILLIAMYOUNG

Operations Specialist

Brown

and

Caldwell Consultants

Walnut

Creek,

California

Chapter

1

Introduction

ROBERT

L.

SANKS

CONTRIBUTORS

Roger

J.

Cronin

Marc

T.

Pritchard

Brian

G.

Stone

Roy

L.Wilson

This book

is

written

for a

wide variety

of

readers:

the

expert

and the

beginner

in a

design

office,

the

project

leader

of a

design team,

the

city engineer

or

chief engi-

neer

of a

water

or

sewerage authority

(or

their subordi-

nates)

who may

review plans

and

specifications,

and

manufacturers'

representatives

who

should know

how

their equipment

is

best applied

to a

pumping station.

Recommendations

for the

utilization

of the

book

by

each group

of

readers

are

given

in

Section 1-7.

The aim of the

volume

is to

show

how to

apply

the

fundamentals

of the

various disciplines

and

subjects

into

a

well-integrated pumping

station

—

reliable,

easy

to

operate

and

maintain,

and

free

from

serious design

mistakes.

To

facilitate

the

selection

of

good design engi-

neers,

the

publisher hereby gives permission

to

pho-

tocopy

Chapter

1

only

of

this book

for

distribution

to

municipalities

or

utilities

and

their representa-

tives.

1-1.

Authors

and

Contributors

Each author

or

contributor

is an

expert with many

years

of

experience

in the

subject discussed. Further-

more,

all

chapters were reviewed

and

critiqued

by

four

to

eight other equally

qualified

experts including

the

editors. (Editors' names

are not

listed unless

an

editor

is a

principal author.)

The

reviewers

are

listed

as

contributors (except,

of

course,

for the

editors),

but not all

contributors

are

reviewers.

A

contributor

is one who has

helped

in any

way,

from

writing

a

short segment

to

giving advice.

Engineers

do not

always agree,

and the

viewpoints

expressed

do not

necessarily

reflect

those

of

each indi-

vidual

contributor

or

even

of the

author. Where

an

unresolvable

conflict

occurs, both viewpoints

are

given.

No

effort

has

been spared

to

make this book

the

most authoritative

possible.

In

spite

of

these

efforts,

there

are

more

differences

than

can be

encompassed

and

some errors

may

have occurred,

so

read thought-

fully

and

with care.

1-2.

Responsibilities

of

Project

Engineers

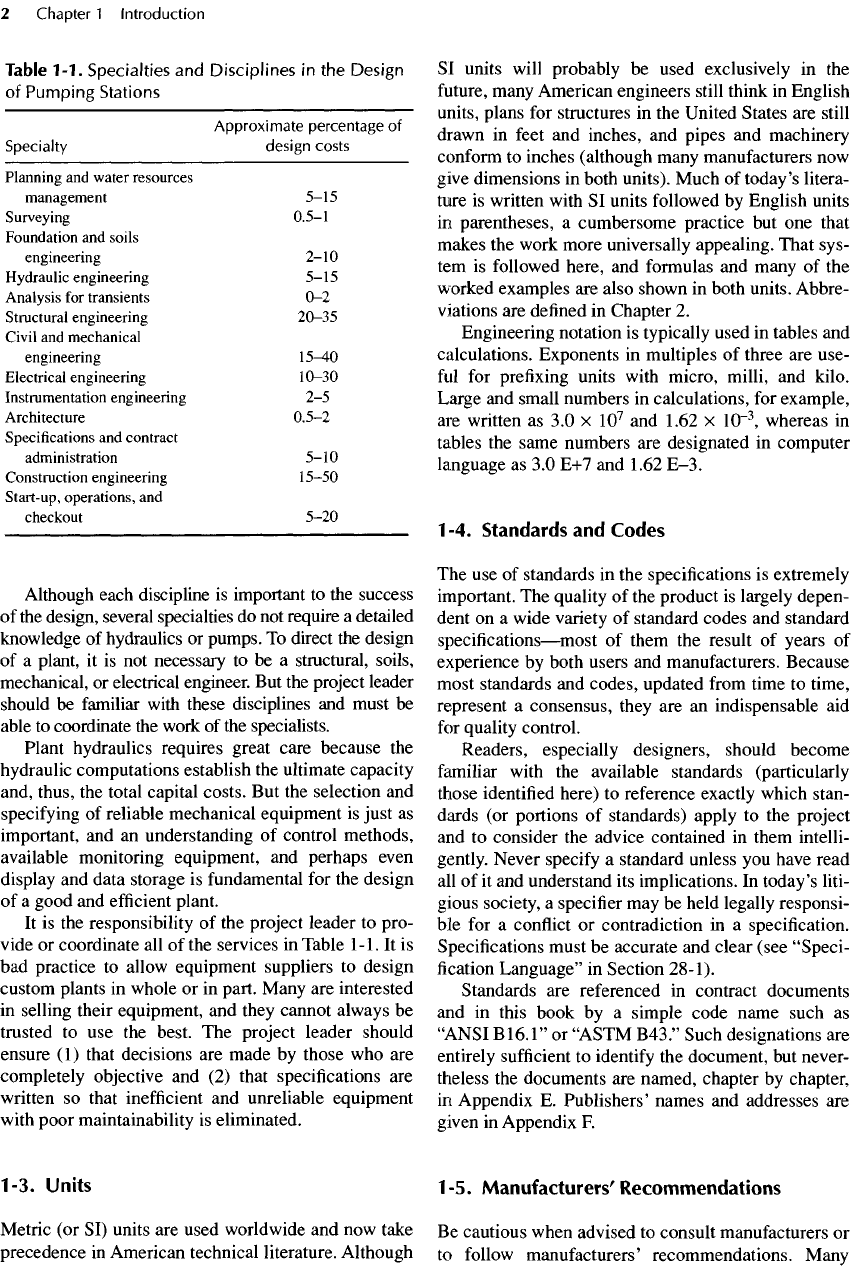

The

design

of a

pumping station depends

on

several

specialties, which

are

listed

in

Table

1-1

more

or

less

in

chronological order together with

the

approximate

range

of

percentages

of

engineering

or

design costs.

Not all

specialties

for all

pumping stations

are

shown.

For

example, river engineering (not shown) might

be a

significant

part

of

design costs

for a raw

water pump-

ing

station taking water

from

a

river meandering

in a

sandy

plain,

and a raw

sewage

lift

station

at a

treat-

ment plant

may be so

closely tied

to the

treatment

plant

that

it

would

be

impossible

to

assign engineering

costs

to the

lift

station alone.

Table

1-1.

Specialties

and

Disciplines

in the

Design

of

Pumping

Stations

Approximate

percentage

of

Specialty

design

costs

Planning

and

water

resources

management

5-15

Surveying

0.5-1

Foundation

and

soils

engineering

2-10

Hydraulic

engineering

5-15

Analysis

for

transients

0-2

Structural

engineering

20-35

Civil

and

mechanical

engineering

15—40

Electrical

engineering

10-30

Instrumentation

engineering

2-5

Architecture

0.5-2

Specifications

and

contract

administration

5-10

Construction

engineering

15-50

Start-up,

operations,

and

checkout

5-20

Although

each discipline

is

important

to the

success

of

the

design, several specialties

do not

require

a

detailed

knowledge

of

hydraulics

or

pumps.

To

direct

the

design

of

a

plant,

it is not

necessary

to be a

structural, soils,

mechanical,

or

electrical engineer.

But the

project leader

should

be

familiar with these disciplines

and

must

be

able

to

coordinate

the

work

of the

specialists.

Plant hydraulics requires great care because

the

hydraulic

computations establish

the

ultimate capacity

and, thus,

the

total capital costs.

But the

selection

and

specifying

of

reliable mechanical equipment

is

just

as

important,

and an

understanding

of

control methods,

available monitoring equipment,

and

perhaps even

display

and

data storage

is

fundamental

for the

design

of

a

good

and

efficient

plant.

It

is the

responsibility

of the

project leader

to

pro-

vide

or

coordinate

all of the

services

in

Table

1-1.

It is

bad

practice

to

allow equipment suppliers

to

design

custom

plants

in

whole

or in

part. Many

are

interested

in

selling their equipment,

and

they cannot always

be

trusted

to use the

best.

The

project leader should

ensure

(1)

that decisions

are

made

by

those

who are

completely objective

and (2)

that specifications

are

written

so

that

inefficient

and

unreliable equipment

with

poor maintainability

is

eliminated.

1-3.

Units

Metric

(or SI)

units

are

used worldwide

and now

take

precedence

in

American technical literature. Although

SI

units will probably

be

used exclusively

in the

future,

many American engineers still think

in

English

units, plans

for

structures

in the

United States

are

still

drawn

in

feet

and

inches,

and

pipes

and

machinery

conform

to

inches (although many manufacturers

now

give dimensions

in

both units). Much

of

today's litera-

ture

is

written with

SI

units followed

by

English units

in

parentheses,

a

cumbersome practice

but one

that

makes

the

work more universally appealing. That sys-

tem is

followed here,

and

formulas

and

many

of the

worked

examples

are

also shown

in

both units. Abbre-

viations

are

defined

in

Chapter

2.

Engineering notation

is

typically used

in

tables

and

calculations. Exponents

in

multiples

of

three

are

use-

ful

for

prefixing units with micro,

milli,

and

kilo.

Large

and

small numbers

in

calculations,

for

example,

are

written

as 3.0 x

10

7

and

1.62

x

10~

3

,

whereas

in

ta.bles

the

same numbers

are

designated

in

computer

language

as 3.0 E+7 and

1.62 E-3.

1 -4.

Standards

and

Codes

The use of

standards

in the

specifications

is

extremely

important.

The

quality

of the

product

is

largely depen-

dent

on a

wide variety

of

standard codes

and

standard

specifications—most

of

them

the

result

of

years

of

experience

by

both users

and

manufacturers. Because

most standards

and

codes, updated

from

time

to

time,

represent a

consensus,

they

are an

indispensable

aid

for

quality control.

Readers, especially designers, should become

familiar

with

the

available standards (particularly

those identified here)

to

reference exactly which stan-

dards

(or

portions

of

standards) apply

to the

project

and

to

consider

the

advice contained

in

them intelli-

gently. Never specify

a

standard unless

you

have read

all of it and

understand

its

implications.

In

today's

liti-

gious society,

a

specifier

may be

held legally responsi-

ble for a

conflict

or

contradiction

in a

specification.

Specifications must

be

accurate

and

clear (see

"Speci-

fication

Language"

in

Section 28-1).

Standards

are

referenced

in

contract documents

and

in

this book

by a

simple

code

name such

as

"ANSI

B

16.1"

or

"ASTM

B43."

Such designations

are

entirely

sufficient

to

identify

the

document,

but

never-

theless

the

documents

are

named, chapter

by

chapter,

in

Appendix

E.

Publishers' names

and

addresses

are

given

in

Appendix

F.

1-5.

Manufacturers'

Recommendations

Be

cautious when advised

to

consult manufacturers

or

to

follow manufacturers' recommendations. Many

manufacturers

get

business based

on one

consider-

ation

—

low

price

—

so

they tend

to

stretch their criteria

for

use to the

limit. Thus, their products perform

as

they

say

only

if

•

their instructions

or

recommendations

are

followed

exactly;

•

their product

is

used

in a

service

perfect

for its

use.

These

constraints

are

rarely

met in field

installations,

so

designers must consider

the

merit

of the

manufac-

turer's recommendations

and

often

establish

a

more

conservative design.

1-6.

Safety

Many

fatal

accidents occur each year

in the

water

and

wastewater

industries

in the

United States. Designers

should

be

aware

of the

hazards

and

circumvent them

insofar

as

possible both

by

good design

and by

ade-

quate

warnings

and

other instructions

in the

operation

and

maintenance (O&M) manual. Every designer

should

read

Life

Safety

Code

[1] and two of the

NIOSH reports [2,3]

as

well

as

Sections 23-1

and

23-2

in

this volume,

in

which some

of the

hazards

in

both

water

and

wastewater pumping

are

explored.

1-7.

How to

Utilize

This

Book

Many

of the

facets

of

pumping station design

are so

interrelated that coherent discussions

of

different

top-

ics

sometimes involve

the

same subject

in

several

places

and

from

different

viewpoints. Hence, none

of

the

chapters should

be

studied

in

isolation. This

is an

integrated work

and

should

be

read

as a

whole.

For

example, station head-capacity (H-Q) curves

are

cus-

tomarily

shown

as

single lines

for

simplicity.

A

reader

who

misses Figure

18-17

and the

discussion

of

friction

losses

in

Section

3-2

might

not

realize that

H-Q

curves should

be

considered

as

broad bands.

Note that there

is

extensive cross-referencing;

the

locator

in the

prefatory section

and the

relatively

complete index

can be

used

to find the

references

to a

given

subject.

Recommended

Minimum

Reading

As

a

minimum,

the

user

of

this book should read

Chapters

27 and 24

(particularly Sections 24-9

and

24-10). Those

who are

concerned

with

selecting con-

sultants

should read Section

1-8.

Beginners

Beginners should read

the

entire book

and

resist

the

temptation

to

study

a

single subject

or a

single chapter.

Project

Leaders

Project

leaders

must have

a

working knowledge

of all

phases

of the

project

and

must

be

able

to

communi-

cate with other members

of the

team

to

plan

the

project

effectively.

They must

coordinate

all

phases,

distinguish

the

good

from

the

shoddy,

and

shoulder

the

responsibility

for

producing

a

well-designed

facil-

ity.

Hence,

they

too

should

be

well acquainted with

the

entire book.

Experts

Experts

are

themselves

the

best judges

of

what

to

study.

It

would

be

wise

to

scan

the

entire volume

to

note

the

depth

and

thoroughness

of

coverage.

Public

Utility

Managers

Public utility managers

and

others

who

deal with

or

have control over

the

pumping station design would

be

wise

to

read

the

following:

•

Chapter

25

from

the

beginning through Section

25-6 and, especially, Tables 25-3, 25-4,

and

25-5

(for

wastewater pumping)

and

Tables 25-6

and

25-7

(for

water pumping)

• The first few

pages

of

Chapters

17, 18, or 19 for

wastewater, water,

and

sludge pumping,

respec-

tively

•

Chapter

15,

Sections 15-1

and

15-11 and,

espe-

cially, Table 15-3

and the

results

of

Example 29-1

if

variable-

speed

operation

is

considered

•

Before beginning

to

review plans, read Chapter

27,

because much aggravation

can be

avoided

and

con-

siderable

funds

may be

saved

by

following

the

advice

it

contains.

Manufacturers

When advising consultants,

it is not

enough

for

manu-

facturers

and

their representatives

to

know their

own

products. They should also

be

able

to

help with

the

engineering involved

in the

incorporation

of

their

products into

the

station.

At a

minimum,

the

chapters

dealing with their products should

be

read together

with

Chapters

17,

18,

and

19.

Scanning

the

book

may

reveal

other sections

of

importance.

1-8.

How to

Select

Consulting

Engineering

Firms

The

public

at

large tends

to

believe that registration

of

engineers ensures competency,

but

that

is not

true.

Frankly, there just

are not

enough good engineers

for

every

project. Many pumping stations (and treatment

works)

are flawed, and a

distressing number

are

quite

badly

designed.

So it is

important

to

retain truly com-

petent designers

who

will

(1)

produce

a

better facility

than

would mediocre

or

inexperienced engineers

and

(2)

probably save

the

client

significant

life-cycle

costs. Unfortunately, some public bodies

are

obsessed

with

the

low-bid approach

for

choosing engineers

in

the

mistaken thought that money

is

saved

thereby

—

a

penny-wise, pound-foolish notion that fosters hasty,

ill-considered design, prevents adequate investigation

of

viable alternatives,

and

actually

favors

the

inexperi-

enced

or

incompetent

who are

willing

to

work

for low

wages.

The

nineteenth-century words

of

John Ruskin,

"There

is

hardly

anything

in the

world that some

man

cannot

make

a

little

worse

and

sell

a

little cheaper

and

the

people

who

consider

price

only

are

this

mans

lawful

prey"

also apply

to the

services

of any

profes-

sional, including artists, engineers, lawyers,

or

sur-

geons.

In

fact,

as

engineering

fees

are

typically only

about

one-eighth

of the

construction cost,

a

major sav-

ing in

fees

is

insignificant compared with

a

minor sav-

ing

in

construction.

The

spread

of

construction

bid

prices

is

often

greater than

the

entire engineering fee,

so the

place

to

save money

is in

construction.

A

thoughtful,

resourceful designer might save more than

the

entire consulting

fee in

life-cycle cost.

Any

organization that contemplates selecting

an

engineering

firm on the

basis

of low bid

should

be

aware

of the

inevitable results.

As any

private enter-

prise

must

make

a

profit

to

stay

in

business,

the

fol-

lowing

disadvantages

will

occur when

a firm is

forced

to

compete with others

for the

lowest bid.

• The

work

will

be bid

exactly

as

written

by the

agency.

If the

scope

fails

to

include

all the

tasks

necessary

for

completing

the

project, those tasks

will

have

to be

completed

by

change orders that

may

negate

the

supposed low-bid savings.

•

Options

for

long-term cost-saving and/or innova-

tive,

low-cost alternatives will

not be

considered.

Instead,

"cookbook"

designs

and

copies

of

previous

designs will

be

used. Although such designs

may

"work"

(water

may be

pumped),

the

design

is

unlikely

to be

optimal

or the

most cost

effective

for

the new

project.

• The

quality

of

plans

and

specifications will

decline.

Fewer hours will

be

allocated

to

coordination meet-

ings, design reviews,

and

interdisciplinary coordina-

tion.

Consequently, there will

be

more construction

change orders (always expensive).

The

effort

made

in

preparing detailed specifications will

be the

mini-

mum

possible.

"Canned"

specifications

or

specifica-

tions

from

a

previous

job

will

be

used with

a

minimum

of

editing

for

current project needs. Con-

struction inspection will

often

be

under

the

direction

of

young

and

inexperienced engineers.

Low bid is

never

an

adequate basis

for

selection

unless

the

product

can be

defined

and

specified com-

pletely

and

accurately. Artistry

and

thoughtfulness

in

engineering

or in any

product

of

thought cannot

be so

specified.

Sometimes, there

is an

attempt

to

"save"

money

by

dispensing with engineering services during construc-

tion,

by

in-house inspection,

or by

retaining

the

ser-

vices

of a

separate consultant

to

provide engineering

services during construction.

A

design

is not

really

completed until

after

the

project

has

entered service

and

the

adjustments required during

the

commission-

ing

period have been made. When

any of the

above

arrangements

are

used,

the

inevitable result

is

that

the

designer

is

shielded

from

the

day-to-day bidding

and

construction events that inevitably shape

and

refine

the

completed project. Loss

of

direct

contact with

the

project

by the

designer

as it

progresses toward com-

pletion will inevitably mean

the

design will

be

com-

promised. Given this loss

of

contact,

it is

unreasonable

for

the

owner

to

expect

the

completed project

to be

completely satisfactory, just

as it was

unreasonable

for

the

owner

to

expect that

the

design, when

it was

com-

pleted

for

bidding purposes,

is

perfect

in

every way.

The

best construction

can be

obtained only

by

employing experienced inspectors under

the

control

of

(or

at

least answerable

to) the

design

firm.

Some

requests

for

substitutions

or

change orders

are

inevita-

ble,

and it is

better that

the

designer

be in

charge

of

these

to

protect

the

quality

of the

project

and to

avoid

unnecessary

added costs. Design services

for a

rea-

sonably large project typically cost about

6 to 10% of

project

costs,

and

complete services (including

design, inspection,

and

start-up) cost about

12

to

18%.

Trying

to

save

on

this minor

fraction

of

cost

and

major

fraction

of

importance cannot

be

justified.

Good design begins with

the

selection

of

good

designers

by

following

the

aphorism

"By

their fruits,

ye

shall know them." First, discard applications

from

firms

that

have

not

done related, recent work

of

roughly

the

same magnitude. This screening step

reduces

the

applications

by,

perhaps,

half.

Second,

conduct

telephone interviews with

the

operation,

maintenance,

and

supervisory

staffs

at

representative

facilities

designed

by the

remaining applicants.

Ask

searching questions related

to (1) the

quality

of

design,

(2)

whether

the

specifications resulted

in

high-quality

equipment,

(3)

ease

of

operation

and

maintenance,

(4)

whether

the

work space

is

pleasant

and

convenient,

(5)

whether

the

designers were both

competent

and

cooperative during

the

project

and

after

completion,

and (6) the

projects' success

in

meeting

the

purpose

of the

facility. These telephone

interviews

may

well eliminate

all but a

very

few

appli-

cants. Third, select

an ad hoc

committee

of two or

three members

of the

group that

is

responsible

for

choosing

the

consulting engineering

firm

and, accom-

panied

by an

engineering adviser

who is

both expert

in

the field and

disinterested

in the

choice, visit

a

rep-

resentative

facility

of

each remaining

firm.

Allow

a

day

for

each visit. Tour

the

facility

with

the

designer

(or

a

representative)

who

will,

of

course, praise

its

vir-

tues

and

suppress

or

minimize

its

faults.

Dismiss

the

designer

and

tour

it

again with

an

operator

and a

maintenance worker

to

hear their objective views.

Finally, tour

it

again with neither operator

nor

consult-

ants

so

that

the

engineering adviser

can

frankly

explain

the

good

and bad

features and,

to a

large

degree, assess

the

competency

of the

designers. Such

a

visit

is

most revealing,

and a

wide disparity

in the

competence

and

thoughtfulness

of

designers

for all

but

the

simplest, smallest facilities will become appar-

ent. Such visits

may be

expensive,

but if the

cost

of

the

proposed

facility

is

expected

to

exceed half

a

mil-

lion dollars,

the

returns

far

outweigh

the

cost.

The

above process

may

narrow

the field to two or

three applicants. Sometimes, none

of the

applicants

appears

qualified

and it may be

necessary

to

advertise

for

consultants again.

Do not

overlook

the

advantages

of

a

consortium

of a

local

firm and

another

firm

with

great experience. However,

the

experienced

firm

must

have

technical control over

the

project. Most engineers

can

do

good work with only

a

minimum

of

guidance

at

the

right

times

to the

benefit

of all

concerned.

In

such

situations,

the

above selection process, including visi-

tations, should

be

redirected

to the

experienced

firm.

By

this time,

the

selection

is

usually apparent

and

the

interview

of firms on the

"short

list"

is

nearly

a

formality.

Beware

of

"bait

and

switch" tactics wherein

experienced engineers represent their

firm at the

inter-

view

and, thereafter, assign junior engineers

to do the

work.

Make

it

plain that such practices will

not be

tol-

erated,

and

that those experienced engineers whose

facilities

were visited will themselves supervise

the

design. Follow

up to be

sure they

do.

Negotiate

a

con-

tract

for

engineering services that will allow

the

designers enough leeway

to do a

proper

job and to

investigate promising alternatives. Cost plus

a fixed

fee

with

an

upper limit protects both client

and

engi-

neer.

If no

agreement

can be

reached, negotiate with

the

best

of the

other

firms

that made

the

short list

or

else advertise

for

consultants again.

The

method outlined above

is

unsurpassed

for

get-

ting

the

best possible facilities compatible with

the

lowest possible overall

cost.

Some states have recog-

nized

the

need

to

discourage bidding

for the

selection

of

engineers

by

enacting statutes against

the

practice.

The

State

of

Nevada

[4]

requires selection based

on

qualifications.

The

state

law of New

Mexico encour-

ages

the

qualification-based selection

of

engineers

and

also requires

the

services

of a

professional technical

adviser

to

assist

in

defining

the

scope

of

work, evalu-

ating

proposals,

and

negotiating

the

contract.

The

price

is

determined

by

formal

negotiations

after

selecting

the

consultant

[5].

See

Sanks

[6], Shaw [7],

and

Whitley

[8] for

further

information.

Once

a

selection

has

been made

and a

contract

negotiated,

be

prepared

to

work closely with

the

con-

sultant.

A

working team managed

by an

individual

authorized

to

make budget

and

technical decisions

for

the

owner should meet

frequently

with

the

consultant

to

monitor

and

advise

as the

project develops. With

such

a

management, timely

decisions

affecting

the

project

can be

made

and the finished

product will

more accurately

reflect

the

owner's needs.

When

the

project

is

completed,

put

into service,

and

all

adjustments made,

the

engineer should provide

a set of

"as-built"

plans

to the

owner.

These

should

be

impressed with

the

responsible engineer's seal

and

signed. Some owners prefer

the

plans

to be on

dis-

kettes,

but

such

"electronic

plans"

should omit

the

seal

and

signature, because

the

engineer

has no

con-

trol over subsequent alterations

to the

diskettes.

1-9.

Value

Engineering

"Value

engineering"

is a

formalized procedure

for

independently reviewing

the

proposed facilities before

the

design

is

completed.

The

Corps

of

Engineers

and

the

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

are

among

those

who

either encourage

or

require these formal-

ized

studies

of first

costs together with operation,

maintenance,

and

replacement costs,

all of

which

are

sometimes referred

to as

"life-cycle

costs."

If a

value

engineering study

is

required,

the

owner should

pay

for

it as an

extra.

A

team

of

experienced engineering specialists

in

the

fields

appropriate

to the

study

is

assembled under

the

leadership

of a

"certified value

engineer."

The

design engineer must assemble

a

presentation package

for

the

reviewers.

The

assembled team normally

spends about

a

week reviewing

the

designer's

work.

A

team

of

experts

who can

give undivided attention

to

the

broad aspects

of a

problem

can

sometimes save

many

times

the

cost

of the

study. Case

histories

abound where savings

of

large sums

(up to 20% or

even more)

of the

total project

cost

resulted

from

a

peer review,

but

read these reports with caution. Many

case histories give

inflated

values

to the

potential sav-

ings,

and

sometimes

the

recommendations

are not

consistent with overall project objectives.

To

be

most

effective,

such

a

study should

be

made

as

soon

as the

surveys

are

complete,

the

data

are

gath-

ered,

and a

preliminary design concept

is

established,

but

before

any

detailed design

has

commenced

—

probably

when

the

engineering

is

approximately

10 to

15%

complete.

The

owner

and the

engineer review

the

report

and may

reject (with reasons) those recommen-

dations that they consider inappropriate

in

their

response

to the

funding

agency.

Consulting engineers have

often

been forced

to

submit

bids

for

their services

and to

reduce their costs

to a

minimum,

with

the

result that adequate investiga-

tion

of

alternatives

has

been curtailed.

If,

however,

the

advice

in

Section

1-8

has

been followed,

and if

the

project

has

been subjected

to

careful in-house

evaluation

of

alternatives,

the

redesign costs

and

delays

brought about

by the

value

engineering proce-

dure

will

be

minimized.

If the

work

of the

project

engineer

was

well done,

no

significant

changes

will

be

needed.

The

value engineering

study

is

essentially

a

one-

time review, whereas

by

contrast,

the

designer

is

con-

cerned

with

costs throughout

the

project.

The

objec-

tive

is

that blend

of

economy

in the

cost

of

construction,

operation,

and

maintenance together

with

intangibles (such

as

environmental

effects

and

the

ease

of

operation

and

maintenance) that

can be

termed

the

"most cost-effective" solution.

A

designer's attention

is

directed

to

increasingly smaller

elements

as the

design proceeds.

An

important tool

in

the

process

is the

"comparative cost estimates"

of

alternatives. Such estimates

do not

require detailed

quantity

takeoffs

and can

made before

the

design

details

are

developed. Only those elements

of the

project

that

may

vary

because

of the

materials

or

equipment

under evaluation

are

considered.

Every

project

of any

size needs

to be

subjected

to

appropriate comparative cost estimates, regardless

of

whether

a

value

engineering

study

is to be

made.

1-10.

Ensuring

Quality

and

Economy

Pressure

on

engineers

to

achieve

the

lowest costs

in

the

design

of

utility system installations

has

been

increasing. Based

on

past experience, Jones

[9]

points

out

that high-quality design

and

construction features

result

in the

lowest overall costs.

The

public

has

little

patience

for

utility system

failures

—

particularly

for

failures

in

water

and

waste

water systems. Conse-

quently, features that incorporate

a

high

degree

of

reli-

ability

are

required.

These

features

include:

•

Heavy-duty construction

of all

equipment,

not

just

the

main pumps

and

drivers.

See

Sections 16-3,

28-5,

and

Appendix

C for

quality assurance

for

pumping

equipment.

•

Adequate ventilation

to

ensure

a

suitable environ-

ment

for

both equipment

and

workers.

Today's

elec-

tronic equipment requires

far

better environments

than

the

mechanical relays

and

other devices

of the

past.

Air

conditioning

to

remove

particulates

and

corrosive gases such

as

hydrogen

sulfide

and

some-

times

to

cool

the

enclosure

is

often

necessary.

•

Support systems (such

as

on-site generators, sump

pumps,

service water, compressed air,

and

hoisting

equipment)

should provide

the

service necessary

without

fail.

•

Features that make operation

and

maintenance sim-

ple and

convenient include self-cleaning

wet

wells,

simple

control systems,

and

ample access

for

main-

tenance

and

operation.

Cost

is the

proper measure

of

success.

The

true

cost

of any

facility should

not

only include capital,

operation, energy,

and

maintenance costs

but

also

the

cost

of

failure

to

serve

the

public reliably. When

all

costs

are

properly

assessed,

the

initial costs

of

design

and

construction

are

often

a

small part

of the

tax-

payer's burden. Quality

in

design

and

construction

is

the

best overall investment.

Not

only does

it

save

money,

but it

makes

life

easier

for

management, oper-

ation,

and

maintenance personnel.

Joint

Ventures

Joint ventures between small, local consulting

firms

and

highly experienced

firms

result

in

several benefits

including

closer contact

and

cooperation with

the

cli-

ent

(at

lower cost because

of

access

and

lower over-

head),

closer

contact during construction,

and the

education

of the

local

firm at no

cost.

The

last

benefit

may

make

the

local

firm

competent enough

to

design

similar

facilities with

no

future

help. Note that

the

experienced

firm

must have control.

A

good start

in