Pugnaire F.I. Valladares F. Functional Plant Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

light intensity, temperature, humidity, and CO

2

concentration result in variable rates of

photosynthesis and transpiration throughout the canopy, describing the interaction between

canopy structure and its environment is essential to providing realistic predictions. Of the

microclimatic variables affecting gas-flux rates, variability in incident light intensity is usually

responsible for much of the heterogeneity in rates of net photosynthesis and transpiration

within the canopy. This occurs primarily because of the strong light and temperature dependence

of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance, but also because of the effect of vapor-

pressure deficit on transpiration as manifested by radiation-induced increases in leaf temp-

erature. Other factors that add to variability of gas-flux rates within the canopy include

photosynthetic characteristics that vary with depth in the canopy (Beyschlag et al. 1990,

Niinemets 1997, Drouet and Bonhomme 2004) and turbulence in the canopy, which can

significantly alter temperature and humidity gradients.

Foliage intercepts both longwave (>3000 nm) and shortwave (400–3000 nm) radiation.

The portion of the shortwave spectrum where absorption by chlorophyll a and b is high is

often referred to as photosynthetically active photon flux (PFD), and may vary from full

sunlight at the top of the canopy to less than 1% of full sunlight deep within the canopy

(Pearcy and Sims 1994). Shortwave radiation (including PFD) incident on foliage is the sum

of three fluxes: direct solar beam, diffuse radiation from the sky, and diffuse radiation

reflected and transmitted by other foliage elements (Baldocchi and Collineau 1994). Position

of the sun and cloud cover affect fluxes of direct solar beam radiation, and both solar altitude

and azimuth are important in relationship to foliage. Solar direct beam flux depends

on latitude, date, time of day, and orientation of the foliage elements. Diffuse radiation

from the sky emanates from the hemisphere of the sky, and may be relatively constant across

the hemisphere with clear or uniformly overcast skies (but also see Spitters et al. 1986).

Reflection and transmission of direct beam and sky diffuse radiation within the canopy

constitutes leaf diffuse radiation, with flux as a function of the proximity and optical

properties (transmittance and reflectance) of adjacent foliage.

Absorbed shortwave (I

S

) and longwave (I

L

) radiation affect the leaf energy balance, and

in conjunction with convection, leaf transpiration, and leaf longwave emittance, affect leaf

temperature. Longwave radiation emanates to the leaf surface from the sky, soil surface, and

from surrounding foliage, and fluxes are related to the temperature and emissivity of the

radiation surfaces. Convective heat transfer (C

l

) between the leaf and the surrounding air

varies with air and leaf temperatures, and wind speed across the leaf surface. Leaf transpir-

ation rate affects latent heat loss (H

l

) from the leaf. Leaf temperature results from a balance

of energy gains and losses, which may be written as

I

S

a

S

þ I

L

a

L

¼ C

1

þ H

1

þ L

1

, (21:1)

where a

S

and a

L

are the fractions of intercepted shortwave and longwave radiation, respect-

ively, and L

1

is longwave radiation emittance from the leaf surface. Formulations for

convective and latent heat transfer and leaf emittance may be found in Norman (1979) and

Gates (1980). Energy balance routines to calculate leaf temperature require iterative calcula-

tion procedures when linked to stomatal conductance, and resulting model formulations are

generally more complex (Caldwell et al. 1986, Ryel and Beyschlag 1995). However, when

leaves are small or narrow in stature, the assumption that leaf and air temperature are

identical is often made (Ryel et al. 1990, 1993, Wang and Jarvis 1990).

Uniform Monotypic Plant Stands

Single-species plant communities with relatively homogeneous foliage distributions are

modeled with the simplest canopy photosynthesis models. Generally, this model structure is

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 630 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

630 Functional Plant Ecology

limited to grass (e.g., lawns, pastures) or crop canopies, but may also include forest canopies

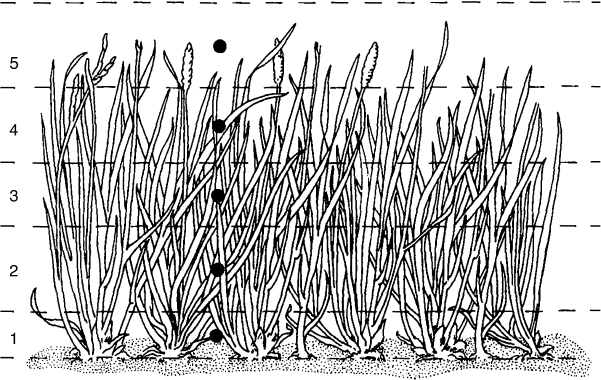

with relatively uniform tree cover. Models for these plant stands divide the canopy into layers

of approximately uniform foliage density and orientation (Figure 21.2), and interception of

radiation and photosynthesis is calculated for points located within the center of these layers.

These models are considered one dimensional since foliage is assumed to be horizontally

uniform, and differences in radiation interception occur only in the vertical dimension.

Details for modeling light relations within uniform monotypic plant stands are contained in

the Section ‘‘Model Development’’.

Uniform Multispecies Plant Canopies

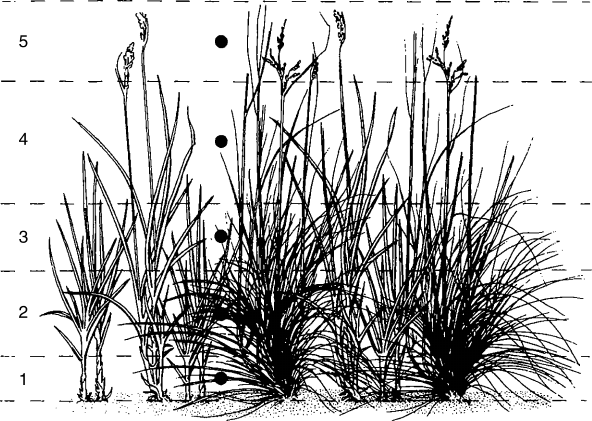

Canopies with relatively homogeneous mixtures of two or more species (e.g., grasslands and

crop=weed mixtures) can be modeled as simple extensions of the model for uniform mono-

typic plant stands. Relatively uniformly distributed foliage is assumed for all species, but the

vertical distribution may vary by species. A simple situation arises when one species overtops

another (e.g., Tenhunen et al. 1994), but the typical canopy has foliage elements mixed within

canopy layers (Figure 21.3) (e.g., Ryel et al. 1990, Beyschlag et al. 1992). As with the uniform

multispecies plant canopy model, intercepted radiation and photosynthesis is calculated for

points located within the center of layers defined by uniformity in foliage density and

orientation for each species. Details for this model type are contained in the Section

‘‘Model Development’’.

Inhomogeneous Canopies

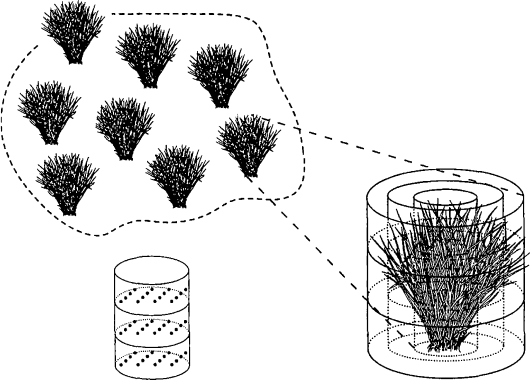

Plant canopies with clumped or discontinuous vegetation cannot be realistically represented

with models that only vary foliage density vertically. Within these canopies, foliage intercep-

tion of light is affected by neighboring vegetation that may not be positioned at uniform

distances or compass direction. If gaps occur within the canopy, light may reach plants

from the sides, and not simply above the foliage. With this complexity, a three-dimensional

light-interception model is necessary to represent these canopies. The common approach to

FIGURE 21.2 Uniform single-species grass canopy subdivided into five layers. Foliage density and

orientation are assumed similar within each layer. Calculations for light interception and photosynthesis

are conducted for the points as shown within the layers.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 631 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

Canopy Photosynthesis Modeling 631

modeling heterogeneous canopies is to fit individual plants or clumps of vegetation with

suitable three-dimensional geometric shapes, including cubes (Fukai and Loomis 1976), cones

(Oker-Blom and Kelloma

¨

ki 1982a,b, Kuuluvainen and Pukkala 1987, Oker-Blom et al. 1989),

ellipses (Charles-Edwards and Thornley 1973, Mann et al. 1979, Norman and Welles 1983,

Wang and Jarvis 1990), and cylinders (Brown and Pandolfo 1969, Ryel et al. 1993). Cescatti

(1997) developed a model structure allowing for radial heterogeneity within individual tree

crowns. Regions within these shapes are assumed to have relatively similar foliage density and

orientation, and light interception and photosynthesis are calculated at points within these

subregions (Figure 21.4).

Big-Leaf Models

In contrast to models for inhomogeneous canopies, big-leaf models simplify rather than

increase canopy structural complexity. In these models (e.g., Sellers et al. 1992, Amthor

1994), properties of the whole canopy are reduced to that of a single leaf, and modified

equations for single-leaf net photosynthesis and conductance are used for calculating whole-

canopy (big-leaf) flux rates. These models have the advantage of fewer parameters, greatly

reduced complexity of development, and substantially less time required for model simula-

tion. Big-leaf models are often used when flux rates are modeled for several vegetation

communities at the landscape scale (Kull and Jarvis 1995).

Although attractive because of their simplicity, big-leaf models have serious limitations.

Parameters for big-leaf models cannot be directly measured, and simple arithmetic means

of parameters for individual leaves are inadequate because most functions involving light

transmission and gas fluxes are nonlinear (Leuning et al. 1995, Jarvis 1995, de Pury and

Farquhar 1997). McNaughton (1994) illustrates this problem by showing that the average

canopy conductance preserving whole-canopy transpiration flux differed from the conduct-

ance necessary to preserve whole-canopy CO

2

assimilation. Despite these problems, big-leaf

models may be suitable if the big leaf is separated into sunlit and shaded elements (de Pury

FIGURE 21.3 Two-species uniform canopy subdivided into five layers. Foliage density and orientation

are assumed similar by species within each layer. Calculations for light interception and photosynthesis

are conducted for the points as shown within the layers.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 632 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

632 Functional Plant Ecology

and Farquhar 1997, Wang 2000, Dai et al. 2004) or calculated fluxes are calibrated to outputs

from more detailed canopy models across an appropriate range of meteorological conditions,

or to whole-canopy flux measurements (Fan et al. 1995, Raulier et al. 1999).

EXAMPLES

Canopy photosynthesis models have been used to address a wide variety of topics including

basic plant ecophysiology (Barnes et al. 1990, Beyschlag et al. 1990, Ryel et al. 1993), environ-

mental change (Ryel et al. 1990, Reynolds et al. 1992), and crop management (Grace et al.

1987a,b). Model outputs can also provide carbon-gain inputs to allocation and growth models

(Johnson and Thornley 1985, Charles-Edwards et al. 1986, Reynolds et al. 1987, Buwalda 1991,

Webb 1991). Two examples of model use are briefly discussed below.

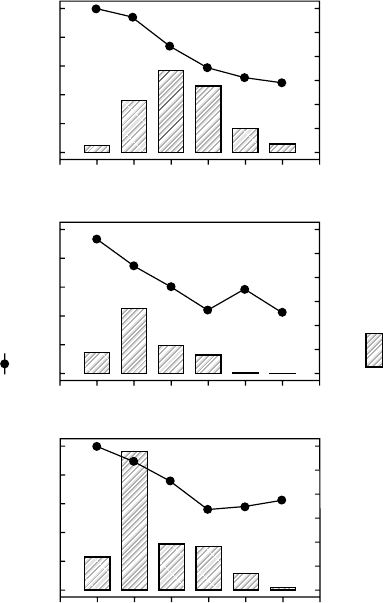

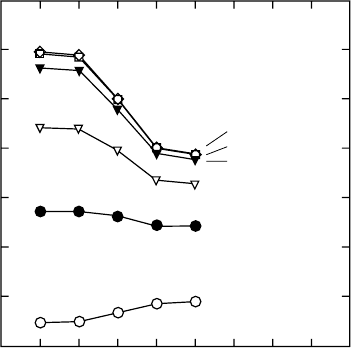

Roadside Grasses

The neophytic grass Puccinellia distans has recently invaded roadsides in central Europe,

which are dominated by the highly competitive grass Elymus repens. Beyschlag et al. (1992)

showed that P. distans could coexist in garden plots with the highly competitive grass E. repens

when regular mowing reduced the competitive advantage of E. repens for light. Ryel et al.

(1996) conducted in situ experiments along roadsides where mowed and unmowed portions

of the same roadway were compared. A multispecies, homogeneous canopy photosynthesis

model was used to estimate reductions in net photosynthesis for P. distans due to the

presence of E. repens within the mowed and unmowed plots. Simulations indicated that little

difference in net photosynthesis occurred between mowed and unmowed plots (Figure 21.5),

eliminating mowing as the primary factor contributing to this coexistence. Subsequent

experiments indicated that shallow soil depth was the primary factor contributing to coexistence

(Beyschlag et al. 1996).

FIGURE 21.4 Individual plant represented as a series of concentric cylinders subdivided into layers as

used by the model of Ryel et al. (1993). Foliage density and orientation are assumed similar within each

layer for an individual plant. Individual plants can be grouped to form a multi-individual canopy with

calculations conducted for each member or representative members. Light attenuation for an individual

plant would be affected by neighboring plants when such a canopy is defined. The matrix of points

indicates locations where light interception and photosynthesis are calculated.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 633 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

Canopy Photosynthesis Modeling 633

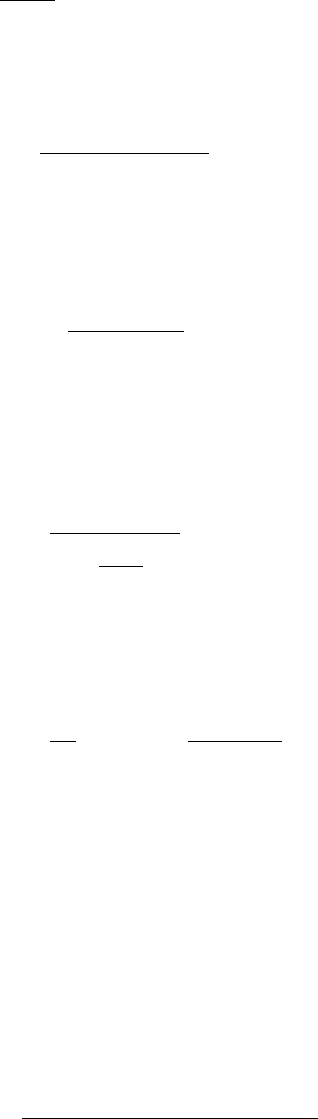

Effects of Needle Loss on Spruce Photosynthesis

Needle loss in conifers is a prevalent symptom of forest decline. Beyschlag et al. (1994)

assessed the effect of needle loss on whole-plant photosynthesis for forests of young Picea

abies. A photosynthesis model for inhomogeneous canopies was used to evaluate light

interception and net photosynthesis in these canopies. Simulation results indicated that in

sparse canopies, needle loss resulted in significant reductions in whole-plant net photo-

synthesis. However, in more dense canopies, little reduction occurred (Figure 21.6) as in canopies

without needle loss, shaded foliage contributed little to whole-plant net photosynthesis.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Canopy photosynthesis models are one method of effectively estimating whole-canopy gas

fluxes (Ruimy et al. 1995), and provide a link between measurable single-leaf photosynthesis

0.6

May 14−

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

100

P. distans

0

20

40

60

80

0.6

July 9, unmowed−

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

100

P. distans

0

20

40

60

80

0.6

July 9, mowed−

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

100

P. distans

0

0−10

10−20

20−30

30−40

40−

50

50

−60

20

40

60

80

Distance from roadside (cm)

LAI (m

2

m

−2

)

Percent of P

mono

FIGURE 21.5 Model calculations of relative photosynthesis rates (lines) for Puccinellia distans for

roadside canopies at six distances from the road edge at the beginning of the mowing experiment in

May (upper) and for unmowed (center) and mowed (lower) plots in July. Relative photosynthesis rates

are expressed as a percent of the rate with Elymus repens removed from the canopy. Total foliage area

of P. distans is also shown (bars). (From Ryel, R.J., Beyschlag, W., Heindl, B., and Ullmann, I., Bot.

Acta, 109, 441, 1996. With permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 634 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

634 Functional Plant Ecology

and rates of photosynthesis in whole plants or canopies. Development of these models is an

ongoing endeavor, with both increasing complexity and simplification characteristic of new

advances. Research objectives will play an important role in influencing the direction of

future model developments.

Model complexity will be increased through the addition of other phenomena and

more realistic structural design. Additional phenomena may include stomatal patchiness

(e.g., Pospisilova

´

and S

ˇ

antrucek 1994, Eckstein et al. 1996), sunflecks (Pearcy and Pfitsch

1994), penumbra (Oker-Blom 1985, Ryel et al. 2001), leaf clumping (Baldocchi et al. 2002,

Cescatti and Zorer 2003), leaf flutter (Roden and Pearcy 1993, Roden 2003), photoinhibition

(Werner et al. 2001), and nonsteady-state stomatal dynamics (Pearcy et al. 1997). Macro- and

microclimate linkages with the canopy may also be improved, with better representations of

air turbulence and concentration gradients, particularly using large-eddy simulation of air-

flow within canopies (Dwyer et al. 1997). Plant structural complexity may also increase as

indicated by the developments of Cescatti (1997). Modular format of model structure allow-

ing for relatively easy replacement of components with new routines enhance the increase in

model complexity (Reynolds et al. 1987).

Canopy photosynthesis models may also be reduced in complexity particularly with

research directed at landscape level fluxes. Approaches similar to the big-leaf models may

be important, but necessitate dealing with problems inherent with model structure and

parameterization (Medlyn et al. 2003). Canopy-level models of photosynthesis based on

remote sensing data may also see more development in the future (Ustin et al. 1993, Field

et al. 1994, Running et al. 2000, Ahl et al. 2004).

Canopy photosynthesis models will be increasingly linked to growth models (e.g.,

Charles-Edwards et al. 1986, Webb 1991, Hoffmann 1995) as growth models become further

developed (e.g., Conner and Fereres 1999). Development of growth models require better

knowledge of linkages between carbon gain and structural changes within the canopy,

Isolated tree

D = 500 cm

D = 200 cm

D = 100 cm

D = 75 cm

D = 50 cm

0

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

1

Number of needle a

g

e classes removed

A

Tree

(mmol day

−1

)

Picea abies [L.] Karst.

234

FIGURE 21.6 Model calculations of absolute changes in daily overall tree photosynthesis of experi-

mental 7 year old spruce tree as a function of the number of needle age classes removed and the stand

density of a simulated canopy. Simulated stands were created with trees equally spaced (D ¼distance

center to center) as indicated. (From Beyschlag, W., Ryel, R.J., and Dietsch, C., Trees Struct. Funct., 9,

51, 1994. With permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 635 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

Canopy Photosynthesis Modeling 635

particularly as affected by light climate. Other linkages may occur between canopy photo-

synthesis models and cellular automation models (Wolfram 1983) to address plant succession

and the formation of stable vegetation patterns (Hogeweg et al. 1985, van Tongeren and

Prentice 1986, Czaran and Bartha 1989, Silvertown et al. 1992).

MODEL DEVELOPMENT

In this section, we review model development for both single-leaf photosynthesis and light

attenuation by foliage. Models described in this section have been selected because they have

been successfully used to address a broad range of ecological questions, and because they

characterize the formulations within this class of models. The level of detail provided is

sufficient for the reader to gain a basic understanding of the modeling process and to aid in

development of similar models. The section concludes with a brief discussion of model

parameterization and validation.

C

3

SINGLE-LEAF PHOTOSYNTHESIS

C

3

photosynthesis is the most widespread metabolic pathway for plant carbon assimilation.

Because of this, substantially more effort has been focused on developing models for C

3

photosynthesis than for C

4

photosynthesis. Portions of C

3

photosynthesis models are also

contained within C

4

photosynthesis models.

Mechanistic

The model developed by Farquhar et al. (1980) and Farquhar and von Caemmerer (1982) for

C

3

single-leaf photosynthesis is the most commonly used mechanistic model. Their original

model assumed limitations in photosynthesis by the activity of the CO

2

-binding enzyme

RuBP-1,5-carboxidismutase (Rubisco) and by the RuBP regeneration capacity of the Calvin

cycle as mediated by electron transport. Sharkey (1985) added an inorganic phosphate

limitation to photosynthesis that was incorporated into models by Sage (1990) and Harley

et al. (1992). This presentation follows the model development of Harley et al. (1992), which is

suitable for ecological applications.

With 0.5 mol of CO

2

released in the cycle for photorespiratory carbon oxidation for each

mol of O

2

reduced, net photosynthesis (A) may be expressed as

A ¼ V

C

0:5 V

O

R

d

¼ V

C

1

0:5 O

t C

i

R

d

, (21:2)

where V

C

and V

O

are carboxylation and oxygenation rates at Rubisco, C

i

and O are the

partial pressures of CO

2

and O

2

in the intercellular air space, R

d

is CO

2

evolution rate in

the light excluding photorespiration, and t is the specificity factor for Rubisco (Jordan and

Ogren 1984).

As discussed earlier, the rate of carboxylation (V

C

) is limited by three factors and is set as

the minimum of

V

C

¼ min W

C

,W

j

,W

p

, (21:3)

where W

C

is the carboxylation rate limited by the quantity, activation state, and

kinetic properties of Rubisco, W

j

is the carboxylation rate limited by the rate of RuBP

regeneration in the Calvin cycle, and W

p

is the carboxylation rate limited by available

inorganic phosphate. A becomes

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 636 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

636 Functional Plant Ecology

A ¼ 1

0:5 O

t C

i

min W

C

,W

j

,W

p

R

d

: (21:4)

Michaelis–Menten kinetics are assumed for W

C

with competitive inhibition by O

2

, and W

C

is

written

W

C

¼

V

C

max

C

i

C

i

þ K

C

1 þ O= K

O

ðÞ

, (21:5)

where V

C

max

is the maximum carboxylation rate, with K

C

and K

O

the Michaelis constants for

carboxylation and oxygenation, respectively.

W

j

is assumed proportional to the electron transport rate (J ) and is written as

W

j

¼

J C

i

4 (C

i

þ O=t)

(21:6)

with the additional assumption that sufficient ATP and NADPH are generated by four

electrons to regenerate RuBP in the Calvin cycle (Farquhar and von Caemmerer 1982). J is

a function of incident photosynthetic photon flux density (PFD) and was formulated empir-

ically by Harley et al. (1992) with the equation of Smith (1937) as

J ¼

a I

1 þ

a

2

I

2

J

2

max

1=2

, (21:7)

where a is quantum efficiency, I is incident PFD, and J

max

is the light-saturated rate of

electron transport.

Carboxylation rate as limited by phosphate (W

p

) is expressed as

W

p

¼ 3 TPU þ

V

O

2

¼ 3 TPU þ

V

C

0:5 O

C

i

t

, (21:8)

where TPU is the rate at which phosphate is released during starch and sucrose production by

triose-phosphate utilization.

The temperature dependencies of factors K

c

, K

O

, R

d

, and t were expressed empirically by

Harley et al. (1992) as

K

c

, K

O

, R

d

, and t ¼ exp c DH

a

=(R T

K

)½, (21:9)

where c is a scaling factor, DH

a

is the energy of activation, R is the gas constant, and T

K

is leaf

temperature.

J

max

and V

C

max

are also temperature dependent and Harley et al. (1992) used activation

and deactivation energies based on Johnson et al. (1942)

J

max

and V

C

max

¼

exp [c DH

a

=(R T

K

)]

1 þ exp [(DS T

K

DH

d

)=(R T

K

)]

, (21:10)

where DH

d

is the deactivation energy and DS is an entropy term.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 637 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

Canopy Photosynthesis Modeling 637

Empirical

The model of Thornley and Johnson (1990) has been widely used and gives good fits to

measured data. Gross photosynthesis (P) is expressed as

P ¼

a I

l

P

m

a I

l

þ P

m

, (21:11)

where a is the quantum efficiency, I

l

is incident PFD, and P

m

is the maximum gross

photosynthesis rate at saturating PFD. A factor (u) for resistance between the CO

2

source

and site of photosynthesis, determined from fitting measured data, can be added to obtain

P ¼

1

2u

a I

l

þ P

m

(a I

l

þ P

m

)

2

4u a I

l

P

m

1=2

no

(21:12)

for 0 < u <1. Johnson et al. (1989) contains a typical application of this model.

Another useful empirical model was developed by Tenhunen et al. (1987), which uses

formulations from Smith (1937) for the light and CO

2

dependency of net photosynthesis.

Equation 21.7 is used for the light dependency of A, and a similar formulation is used for the

CO

2

dependency. This equation is also used for the light dependency of carboxylation

efficiency. Equation 21.10 is used for the temperature dependence of the maximum capacity

of photosynthesis.

C

4

SINGLE-LEAF PHOTOSYNTHESIS

C

4

photosynthesis involves a CO

2

concentrating mechanism coupled with the C

3

photosyn-

thesis cycle. In the concentrating process, phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) is carboxylated in the

mesophyll cells, transferred to the bundle sheath cells, and decarboxylated before entering the

C

3

cycle (Peisker and Henderson 1992). An initial submodel calculates the pool of inorganic

carbon in the bundle sheath cells.

Mechanistic

A simple C

4

photosynthesis model is that of Collatz et al. (1992) who assumed that the

carboxylation catalyzed by PEP carboxylase is linearly related to CO

2

concentration of the

internal mesophyll air space. The model does not consider light dependencies of PEP carboxy-

lase activity and other activation processes (Leegood et al. 1989). Chen et al. (1994) proposed a

more complex model with the C

4

cycle controlled by PEP carboxylase. The rate of this cycle

(V

4

) is described by Michaelis–Menten kinetics and related to mesophyll CO

2

concentration by

V

4

¼

V

4m

C

m

C

m

þ k

p

, (21:13)

where C

m

is mesophyll CO

2

concentration and k

p

is a rate constant. The maximum reaction

velocity (V

4m

) is related to incident PFD (I

p

) by

V

4m

¼

a

p

l

p

1 þ a

2

p

l

2

p

=V

2

pm

1=2

(21:14)

with a

p

a fitted parameter and V

pm

the potential maximum activity of PEP carboxylase. The

C

3

and C

4

cycles are linked as

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 638 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

638 Functional Plant Ecology

V

4

¼ V

b

þ A

n

, (21:15)

where V

b

is the diffusion flux of CO

2

between the bundle sheath and the mesophyll and A

n

(net photosynthesis) is the net CO

2

exchange rate between the atmosphere and the mesophyll

intercellular air space. A

n

is calculated using Equation 21.2 with C

i

replaced with the CO

2

concentration in the bundle sheath cells. Equation 21.13 and Equation 21.15 are solved

iteratively to obtain A

n

by balancing the CO

2

and O

2

concentrations in the bundle sheath

cells (see Chen et al. 1994 for details).

Empirical

Two approaches to empirical C

4

photosynthesis model are discussed here. Dougherty et al.

(1994) used the minimum of photosynthetic capacities limited by light (A

1

) and by intercel-

lular CO

2

(A

2

). A

1

is expressed with a nonrectangular hyperbola as

A

1

¼

A

m

þ aI

2

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

A

2

m

2A

m

aI(2b 1) þa

2

I

2

p

2b

, (21:16)

where a is quantum efficiency, b is an empirical shape parameter, I is incident PFD, and A

m

is

maximum photosynthetic capacity. A

2

is expressed as

A

2

¼ A

m

c

i

c

i

þ 1=E

c

, (21:17)

where E

c

is an empirical index of leaf CO

2

efficiency and c

i

is intracellular CO

2

. The

temperature dependence of A

m

uses Equation 21.10.

Thornley and Johnson (1990) describe two empirical formulations of C

4

photosynthesis.

In one formulation, energy necessary for pumping CO

2

into the bundle sheath is assumed

independent of that available to the bundle sheath for C

3

photosynthesis and photorespira-

tion. In the second model, a common supply of energy to both mesophyll and bundle sheath

is assumed.

STOMATAL CONDUCTANCE

Models for stomatal diffusive conductance are either coupled or uncoupled with leaf photo-

synthesis rates, and are coupled with various environmental factors. Presently all models are

empirical in design. Coupled stomatal models are recommended for addressing questions

more physiological in nature.

Coupled Models

A simple, but effective coupled model for stomatal conductance was developed by Ball et al.

(1987). Stomatal conductance (g

s

) is related linearly to net photosynthesis (A) and relative

humidity (h

s

), and expressed as

g

s

¼ k A (h

s

=c

s

), (21:18)

with c

s

the mole fraction of CO

2

at the leaf surface. Although g

s

does not respond directly to

net photosynthesis, relative humidity, or CO

2

at the leaf surface, this model often corresponds

well to measured data.

This model has been modified by Leuning (1995) to be consistent with the findings of

Mott and Parkhurst (1991) that stomata respond to the rate of transpiration. Interactions

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C021 Final Proof page 639 16.4.2007 4:02pm Compositor Name: BMani

Canopy Photosynthesis Modeling 639