Pugnaire F.I. Valladares F. Functional Plant Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

changes in defense-related gene expression, have been shown to reduce the extent of O

3

injury

(Yalpani et al. 1994, Rao et al. 1996, O

¨

var et al. 1997).

PLANT LEVEL

Where pollutant uptake exceeds the capacity of the detoxification=repair systems to prevent

damage, there may be a host of adverse consequences on plant physiology resulting, ultim-

ately, in the death of plant tissues. The oxidative stress imposed by O

3

, for instance, is

reflected in a decline in the photosynthetic capacity of individual leaves (Kangasja

¨

rvi et al.

1994, Pell et al. 1997), increased rates of maintenance respiration (Darrall 1989, Wellburn

et al. 1997), enhanced retention of fixed carbon in leaves (Cooley and Manning 1987,

Balaguer et al. 1995), and accelerated rates of leaf senescence (Alscher et al. 1997, Pell et al.

1997)—effects that are reflected in reduced growth and reproductive potential. Under some

circumstances, the pollutant can induce localized cell death, resulting in typical visible

symptoms of foliar injury. However, what aspect of performance should be used as an

indication of resistance in an ecological context? In the case of crops, this is relatively

straightforward since the impact of the pollutant on yield and marketable product is clearly

the important feature. However, it is more difficult for natural vegetation. Because annual or

monocarpic species must produce seeds to survive, seed output is an obvious criterion to use.

However, what should be used to rank the performance of perennial species? Many iteropar-

ous perennials live for decades or even centuries (Harberd 1960, Harper 1977). Yet, more

often than not, assessments of resistance have been based on the degree of visible foliar

damage or impacts on plant growth rate relative to that of controls, with little consideration

or understanding of whether these features are important in an ecological context (Davison

and Barnes 1998). It has, for example, become common practice to rank species in terms of

susceptibility on the basis of visible symptoms of injury. This tends to lead to the intuitive

conclusion that the affected species must suffer from some ecological disadvantage in the

field, and conversely that unmarked species do not. This may be a serious misconception.

First, the expression of symptoms is affected by many factors, including soil water deficit,

vapor pressure deficit, photon flux density, temperature (Balls et al. 1996), and possibly UV-B

radiation (Thalmiar et al. 1995). Second, there is usually little relation between relative

sensitivity in terms of visible symptoms and effects on growth or seed production (Heagle

1979, Fernandez-Bayon et al. 1992, Bergmann et al. 1995); some taxa show highly significant

effects of O

3

on growth but no visible symptoms, whereas others exhibit extensive visible

symptoms but no effects on growth (Davison and Barnes 1998 and references therein).

Third, and possibly most importantly, species that show injury are not necessarily debilitated

in competition with other species that do not. This is clearly demonstrated in the work of

Chappelka and colleagues (Chappelka et al. 1997, Barbo et al. 1998) on communities contain-

ing sensitive species such as blackberry (Rubus cuneifolius) and tall milkweed (Asclepias

exaltata), shown to proliferate in field studies, despite the development of extensive visible

symptoms of O

3

injury (Figure 20.5). Observations such as these led Davison and Barnes

(1998) to conclude that ‘‘visible symptoms are best regarded as evidence of a biochemical

response to ozone. They do not necessarily indicate sensitivity in terms of growth reduction

and they are not evidence of an ecological impact.’’

Many other assessments of resistance of wild species have been based on the ratio

of harvest weight in treated plants to that of controls, whereas others have used the ratio of

mean relative growth rate. Most have used aboveground weight, and few have measured root

weight or parameters of ecological importance such as specific root length or root length=leaf

area ratio (Pell et al. 1997). This is important because the choice of measure can influence

both the apparent magnitude of the ozone response and the relative ranking (Macnair 1991,

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 610 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

610 Functional Plant Ecology

Ashmore and Davison 1996). The difficulties are apparent in the hypothetical example given

by Davison and Barnes (1998), where straightforward comparisons of the effects of O

3

on the

growth of a fast-growing ruderal and a slower-growing stress tolerator (Grime 1979) would

yield erroneous results. Attempts to find broad relationships between resistance and adaptive

or ecological characters have proved disappointing. Preliminary studies conducted by Reiling

and Davison (1992) on 32 species revealed a weak negative relationship between the effect of

O

3

and plant relative growth rate in clean air, implying that approximately 30% of the

variation between taxa was related to differences in inherent growth rate. However, in a

more comprehensive study of 43 species, in which one of the principal aims was to investigate

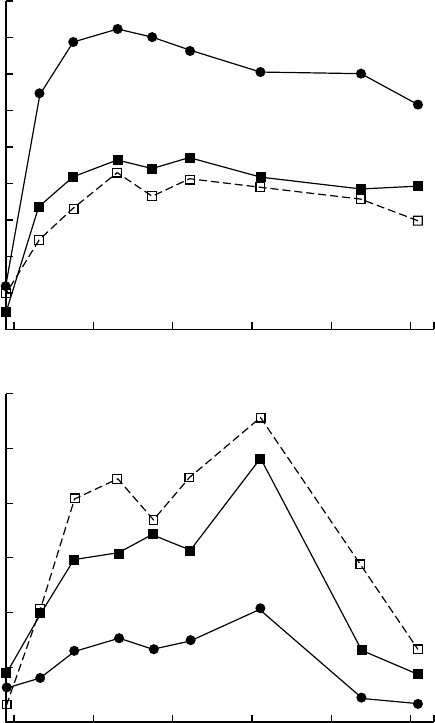

April May June July August

CF

NF

2⫻

45

40

35

30

25

Mean density (m

−2

)

20

15

10

5

0

(a)

April May June July Au

g

ust

CF

NF

2⫻

120

100

80

60

40

20

Mean density (m

−2

)

0

(b)

FIGURE 20.5 Effects of open-top chamber ozone exposure on two understory species in an early

successional forest community; changes in mean density of (a) blackberry (Rubus cuneifolius), a species

that develops extensive visible symptoms of O

3

injury and has therefore often been classified as sensitive,

and (b) bahia grass (Paspalum notatum), a species that does not show visible injury and has therefore

often been classified as resistant. Treatments: NF, nonfiltered ambient air; CF, charcoal-filtered air; 2,

2 ambient O

3

. (From Davison, A.W. and Barnes, J.D., New Phytol., 139, 135, 1998. With permission;

based on original data presented by Barbo, D.N., Chappelka, A.H., and Stolte, K.W., Proc. 8th Bienn.

South. Silvicult. Res. Counc., Auburn, Alabama, 1–3, 1994.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 611 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

Resistance to Air Pollutants: From Cell to Community 611

relationships between O

3

sensitivity and CSR strategy (Grime 1979), O

3

resistance was found

to be significantly correlated with only one other trait, mycorrhizal status, and no relation

existed between O

3

sensitivity and R in clean air or plant growth strategy (Grime et al. 1997).

In contrast, SO

2

resistance was significantly correlated with 12 other traits. However, con-

clusions drawn from such studies are difficult to interpret because the effects on growth may

be influenced by many factors, including seed characteristics and seed provenance; some

experiments have used seeds collected in the field, whereas others have used commercial seeds

or a mixture of sources (Davison and Barnes 1998). Hence, maternal effects caused by the

parental environment (Roach and Wulff 1987) may contribute to some of the differences in

ranking reported for the same species, for example, Phleum alpinum (Mortensen 1994, Pleijel

and Danielsson 1997). There may also be substantial intraspecific variation in the response

of different genotypes within a population to the same air pollution insult (see Section

‘‘Population Level’’).

Much attention has focused on the relative partitioning of dry matter between the root

and the shoot of crop plants, and the observed impacts of specific pollutants (e.g., O

3

) are

often interpreted as universal (O

¨

var et al. 1997). However, experiments with a range of wild

species show that the situation is much more complicated, and subtle effects on allocation

that are probably of greater ecological significance than changes in mass are common. In the

legume Lotus corniculatus, Warwick and Taylor (1995) found that O

3

had no effect on

allometric root=shoot growth, but caused a large reduction in specific root length, and

there are other cases in which decreased allocation to the root has been found to be associated

with compensatory changes in thickness, so length is unaffected (Taylor and Ferris 1996).

Some species (e.g., Arrhenatherum elatius, Rumexacetosa) may even show an increased

allocation to the root when exposed to ozone (Reiling and Davison 1992); others such as

clover show the greatest decrease in allocation not to the roots, but to the storage and

overwintering organs, that is, the stolons (Wilbourn et al. 1995, Fuhrer 1997). One of the

most instructive studies of pollutant impacts on resource allocation in wild species was

performed by Bergmann et al. (1995, 1996). They exposed 17 herbaceous species from

seedling stage to flowering to two O

3

regimes with different dynamics: CF þ70 nL L

1

per

8 h and CF þ60% ambient þ30 nL L

1

. Responses varied with exposure regime, and the

weight of some species was reduced to about 60% of controls, but the most striking differ-

ences were in resource allocation (Figure 20.6). Most showed a proportionate change between

shoot mass and reproductive effort (bottom left quadrant of Figure 20.6), but two species

(Chenopodium album and Matricaria discoidea) showed a greater vegetative shoot weight and

reduced reproductive allocation. Conversely, Papaver dubium and Trifolium arvense exhibited

reduced shoot mass sand increased allocation to seed=flowers. Such shifts in resource alloca-

tion may help to explain why O

3

is sometimes found to stimulate growth and highlight the

need for greater understanding of the control of resource allocation in species that have

different reproductive and survival strategies.

Relative rankings of resistance may also be biased by growth stage=developmental status,

since plants do not appear to be equally sensitive to pollutants at all stages in their life cycle

(Davison and Barnes 1998). Our own work (Lyons and Barnes 1998) on Plantago major, for

example, shows that seedlings are much more sensitive to O

3

than juvenile or mature plants;

O

3

-induced declines in accumulated biomass appeared to be almost entirely due to effects on

seedling relative growth rate in this species, whereas seed production is most affected during

the early stages of flowering (Figure 20.7; Davison and Barnes 1998). Compensatory changes

in growth and morphology may also limit the impacts of prolonged exposure to O

3

(Lyons

and Barnes 1998 and references therein). In the absence of such effects, it is conceivable that

the impacts of O

3

(and other pollutants) would be considerably greater than they are.

The impacts of pollutants in the field may also be modified by a multitude of

factors, including management practices, soil water deficit, mineral nutrition, nutrition,

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 612 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

612 Functional Plant Ecology

other pollutants, frost, disease, and herbivory (Davison and Barnes 1992, Barnes et al. 1996,

Wellburn et al. 1997, Barnes and Wellburn 1998, Davison and Barnes 1998). Work on crops,

for example, indicates that the impacts of O

3

are commonly reduced under conditions in

which soil water deficit results in a decline in stomatal conductance and hence pollutant

uptake (Tingey and Taylor 1981, Darrall 1989, Tingey and Andersen 1991, Wolfenden et al.

1992, Wellburn et al. 1997). However, field observations relating to possible pollutant–water

stress interactions in wild species are rare and anecdotal. Showman (1991) reported that

visible oxidant injury in wild species in Ohio and Indiana was virtually absent in a year when

it was dry and ozone was high, but widespread in a year when it was not as dry and ozone was

lower. Similarly, Davison and Barnes (1998) drew attention to the fact that in heavily polluted

regions of southern Europe, visible symptoms of oxidant injury are common in irrigated

crops, and there are effects on yield; however, in nonirrigated areas subjected to severe

summer drought, there are virtually no records of symptoms in wild species.

POPULATION LEVEL

There is growing evidence that pollutants, like other novel stresses imposed by human

activities, can bring about changes in the genetic composition of populations (Roose et al.

1982, Taylor and Pitelka 1992). The phenomenon was first revealed through the work of

Bell et al. (1991) on the evolution of SO

2

resistance in grassland species in industrialized

regions of the United Kingdom. However, convincing experimental evidence of evolution of

resistance to regional-scale pollutants (such as O

3

) has only recently been reported. In a way,

this is rather surprising, since the requirements to drive the evolution of O

3

resistance in wild

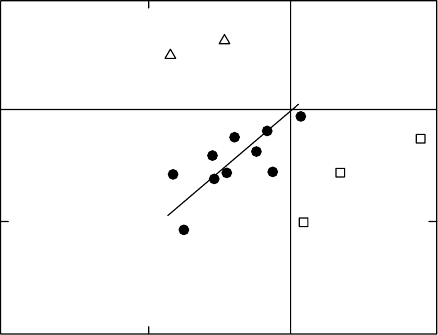

0

0

0.5

1.0

1.5

0.5

Vegetative allocation relative to that in O

3

Trifolium

arvense

Papaver

dubium

Daucus

carota

Matricaria

discoidea

Chenopodum

album

Reproductive allocation relative to that in O

3

1.0 1.5

FIGURE 20.6 Effects of O

3

on the relative allocation of herbaceous species exposed from seedling to

flowering to two O

3

regimes; charcoal-filtered air plus 70 nL L

1

O

3

8 h day

1

or charcoal-filtered air

plus 60% ambient O

3

plus 30 nL L

1

. Changes in allocation expressed as the ratio of that in O

3

to

that in CF air. (From Davison, A.W. and Barnes, J.D., New Phytol., 139, 135, 1998. With permission;

based on the data collected by Bergmann, E., Bender, J., and Weigel, H.-J. Water, Air Soil Pollut., 85,

1437, 1995; Bergmann, E., Bender, J., and Weigel, H.-J., Exceedance of Critical Loads and Levels,

M. Knoflacher, R. Schneider, and G. Soja, eds, Federal Ministry for Environment, Youth and Family,

Vienna, 1996.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 613 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

Resistance to Air Pollutants: From Cell to Community 613

species have been recognized for many years (Lyons et al. 1997, Davison and Barnes 1998).

Our own artificial selection studies (Whitfield et al. 1997) on resistant and sensitive popula-

tions of P. major indicate the potential for evolution of resistance=sensitivity to O

3

within a

matter of only a few generations in this short-lived species. Based on the effects of a 2 week

exposure to 70 nL L

1

O

3

for 7 h day

1

on rosette diameter, selection from an initially sen-

sitive population led to a line with significantly enhanced O

3

resistance, although it was

possible to select a line with greater sensitivity than the original population. Conversely,

selection from an initially resistant population led to a line with increased sensitivity, but not

to a line with enhanced resistance (Figure 20.8). Subsequent experiments have shown that the

resistance of the selected lines is maintained, and differences are reflected in contrasting

effects on growth and seed production.

The earliest suggestion that ambient levels of O

3

maybe high enough to drive the selection

of resistant genotypes in the filed was provided by Dunn (1959), who worked on Lupinus

bicolor in the Los Angeles basin. He attributed differences in the performance of populations

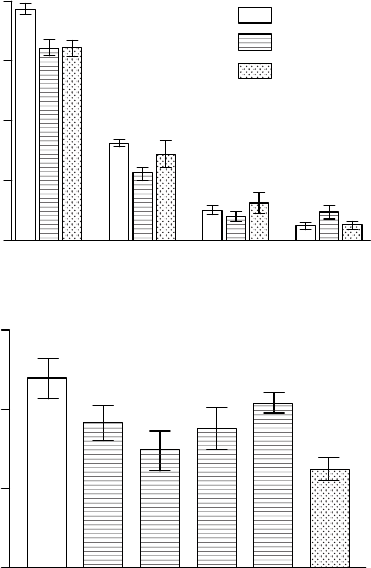

of this species to oxidant smog and commented that ‘‘the stress was so severe that some

∗∗

∗

∗

∗

∗

1–14

0.5

30,000

20,000

10,000

Treatment

No. seeds plant

−1

0

CFA O

1–14

O

14–28

O

28–42

O

42–56

O

3

14–28

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

(a)

(b)

Relative growth rate

28–42 42–56

CFA

O

3

episode

O

3

FIGURE 20.7 Effects of O

3

on (a) growth and (b) seed production in Plantago major Valsain exposed in

duplicate controlled environment chambers to charcoal=Purafil-filtered air (CFA), O

3

(CFA plus 70 nL

L

1

O

3

7 h day

1

), or 14 day episodes of O

3

(i.e., windows) administered for 1–14 days (O

1–14

), 14–28 days

(O

14–28

), 28–42 days (O

28–42

), or 42–56 days (O

42–56

). Asterisks indicate significant (P ¼0.05) differences

from plants maintained in CFA. (From Lyons, T.M. and Barnes, J.D., New Phytol., 138, 83, 1998. With

permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 614 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

614 Functional Plant Ecology

populations failed to set seed’’—an effect expected to contribute to rapid evolution. It is only

through recent work (reviewed by Macnair 1993, Davison and Barnes 1998) on Populus

tremuloides, Trifolium repens,andP. major that convincing experimental evidence has been

provided to support the evolution of resistance to O

3

in the field. Our own studies on P. major

represent the only case in which heritable change in resistance has been shown to occur in the

field over a period of time when O

3

levels increased (Reiling and Davison 1992, 1995).

However, the crucial question in all of the studies conducted to date is whether the observed

differences in resistance between populations have arisen in response to O

3

or to other

correlated environmental factors (Bell et al. 1991). It was suggested by Roose et al. (1982)

that because traits affecting sensitivity to air pollutants may simultaneously reflect adapta-

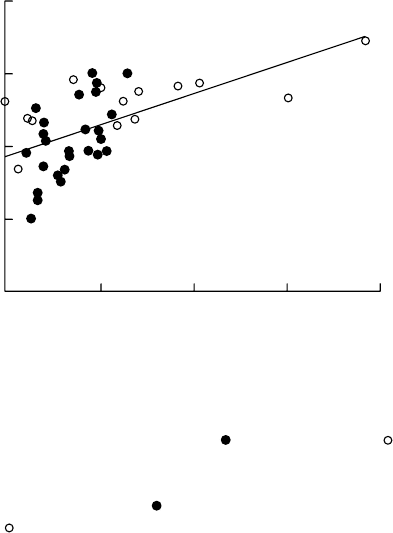

tions to other natural stresses and vice versa, resistance might be indirect. Our own work on

41 European populations of P. major indicates that O

3

resistance is significantly correlated

with the C

3

concentration at or near the site of collection (Figure 20.9), and similar findings

have been reported by Berrang et al. for Populus tremuloides originating from parts of the

United States with different O

3

climates (Davison and Barnes 1998). However, in some cases,

O

3

resistance has also been shown to correlate with other variables (Reiling and Davison

1992). Although the available evidence is consistent with the evolution of O

3

resistance,

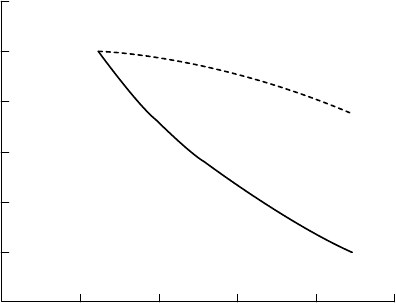

(a)

Generation

Base

Ozone resistance (R

%)

86

88

90

92

94

96

98

100

102

104

1234

(b)

Generation

Base

Ozone resistance (R

%)

86

88

90

92

94

96

98

100

102

104

1234

NS

NS

NS

NS

NS NS NS

FIGURE 20.8 Change in O

3

resistance over four generations in lines selected for sensitivity ( ) and

resistance (

) from two population of Plantago major based on effects on rosette diameter. Data

presented indicate effects on plant relative growth rate (R); R% ¼[R

O

3

=R

CF

] 100. Plants were

exposed in controlled-environment chambers to charcoal=Purafil-filtered air or O

3

(CFA plus 70 nl L

1

O

3

7 h

1

). Dashed lines represent linear regression fits for selections. Data for each generation

in each selected line were subjected to ANOVA. Probabilities (

*

P < 0.05;

**

P < 0.01;

***

P < 0.001)

indicate the significance of O

3

effects on each generation. (From Whitfield, C.P., Davison, A.W., and

Ashenden, T.W., New Phytol., 137, 645, 1997. With permission.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 615 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

Resistance to Air Pollutants: From Cell to Community 615

correlations do not definitively prove a cause–effect relationship. Therefore, it has been

necessary to try to eliminate other possibilities. This has been achieved using partial correl-

ations to remove the effect of climatic differences between collection sites. In some cases,

this has reduced the significance of regressions consistent with the evolution of O

3

resistance

(Berrang et al. 1991, Reiling and Davison 1992); in other studies it has made little difference

to the significance of regressions (Lyons et al. 1991). Although the experimental data are

generally consistent with the evolution of resistance to O

3

, the work graphically illustrates

the difficulties in interpreting the observed spatial variability in pollution resistance.

Based on the assertion of Bell et al. (1991) that ‘‘if populations are evolving it should be

possible to demonstrate a change in resistance over time, as with evolution to other novel

stresses,’’ Davison and Reiling (1995) compared the ozone resistance of P. major populations

grown from seed collected from the same sites over a 6 year period in which ambient O

3

concentrations increased. They demonstrated that two populations increased in resistance,

and Wolff and Morgan-Richards (unpublished data 1997) have recently proven (using

random amplified polymorphic DNA primers [RAPDs]) that the later populations are subsets

of the earlier ones. This is consistent with directional in situ selection rather than a cata-

strophic loss and replacement of the populations by migration. However, difficulties in

interpretation remain, since one of the reasons that O

3

levels increased was because it was

sunnier and warmer. This probably led to a greater incidence of soil moisture deficit and

photoinhibition, but no records are available for the collection sites. Hence, the possibility

that other factors may have contributed to the evolution of O

3

resistance cannot be dismissed.

It is also important to recognize that the evolution of resistance to O

3

may be associated with

costs or a loss of fitness in unpolluted environments, as with other cases of directional

selection motivated by novel stresses (Roose et al. 1982, Macnair 1993, Reiling and Davison

1995), but little is known about the nature of these costs with respect to O

3

resistance

(Davison and Barnes 1998). Furthermore, the rate of evolution of resistance would be

0

70

80

90

100

110

10,000

Ozone exposure, AOT40 (nL L

−1

h)

Ozone resistance (R

%)

20,000 30,000 40,000

FIGURE 20.9 Ozone resistance of seed-grown Plantago major populations plotted against the O

3

exposure (based on the accumulated O

3

exposure above a 40 nL L

1

threshold, that is, AOT40) at the

collection sites. Resistance determined as the mean relative growth rate in O

3

(70 nL L

1

O

3

7 h day

1

)

as a percentage of that in charcoal=Purafil-filtered air.

, UK populations; continental European

populations. Regression 88.7 þ0.00043(AOT40) r ¼0.538, P < 0.0001. (From Davison, A.W. and

Barnes J.D., New Phytol., 139, 135, 1998. With permission; based on data presented by Reiling, K.

and Davison, A.W., New Phytol., 120, 29, 1992 [

] and Lyons, T.M., Barnes, J.D., and Davison, A.W.,

New Phytol., 136, 503, 1997 [

].)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 616 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

616 Functional Plant Ecology

expected to be influenced by many factors, including the mode of reproduction, the form

of sexual reproduction (determining the degree of inbreeding), the dynamics of gene flow

within and between populations, generation time, the presence of seed banks, the extent of the

loss of fitness induced by the pollutant, and the timing of selection in relation to the plants’

life cycle (Roose et al. 1982, Taylor and Pitelka 1992, Macnair 1993, Lyons and Barnes 1998).

Thus, even in areas exposed to potentially damaging pollutant concentrations for long

periods, it is possible to find species that persistently show typical visible symptoms of injury

(Davison and Barnes 1998).

COMMUNITY LEVEL

Studies on isolated taxa indicate that there is wide variation in resistance between species to

gaseous pollutants. This is exemplified in our own screening of the O

3

sensitivity of 30 species

using seed collected from central England, using a standard O

3

exposure of 70 nL L

1

for 7 h

day

1

over 2 weeks (Reiling and Davison 1992). The minimum detectable effect of O

3

on

growth rate in this test was approximately 5%, and species exhibited a range of sensitivities

(Table 20.1); the most sensitive species were affected (in terms of effects on plant relative

growth rate) to a similar extent as some of the most sensitive crop species (e.g., tobacco Bel-

W3). These and other studies (Fuhrer et al. 1997) indicate that herbaceous species exhibit

wide-ranging sensitivity to O

3

. However, there maybe as much variation within species as

between species (see Section ‘‘Population Level’’), and there is no guarantee that controlled

trials are reminiscent of responses in the field, where a range of additional factors must be

considered. Consequently, such studies contribute little other than indicating the range of

potential responses to gaseous pollutants.

Where pollutants emanate from a point source, it is possible to determine effects on

biodiversity by standard ecological and multivariate methods, especially where records can

be repeated over time (Musselman et al. 1992). There is, for example, a wealth of literature

documenting the effects of acidifying air pollutants on epiphytic lichen communities (Nimis

et al. 1991). For regional pollutants such as O

3

it is more difficult, because the pollutant does

not usually show sharp gradients within defined boundaries. Consequently, measurable effects

on the structure of plant communities may be restricted to a few special cases. Westman (1979,

1985), for example, showed that percentage cover and species richness were strongly influenced

by O

3

(and other oxidants) in Californian coastal sage scrub. Preston (1985) reported similar

effects for SO

2

. Interestingly, ordination approaches suggested a greater effect at sites with low

foliar cover than at high ones, but Preston did not comment on this. The same types of studies

are likely to prove unfruitful in less impacted areas, because of the lack of sharp gradients in

oxidant concentrations and the difficulty in locating appropriate control sites. Consequently,

progress in understanding the impacts of regional pollutants (such as O

3

) on plant communities

has, and will probably continue, to depend on experimental exposures using open-top

chambers (OTCs) and relatively simple species mixtures. To date, majority of research have

focused on herbaceous plant communities, especially seminatural grasslands (Ashmore and

Davison 1996, Ka

¨

renlampi and Ska

¨

rby 1996, Fuhrer 1997, Fuhrer et al. 1997, Davison and

Barnes 1998). Consequently, there is very little known about the responses of the wide range of

vegetation types that are found across Europe and the United States, although there is no

reason to believe that these will necessarily respond the same as some of the simple mixtures

that have been studied experimentally (Fuhrer et al. 1997).

Investigations on simple grass=clover mixtures indicate that the effects of O

3

depend on

the relative sensitivity of the competing species (Fuhrer 1997) and on management practices

(Fuhrer et al. 1997, Davison and Barnes 1998). Because red clover (Trifolium pretense)and

timothy (Phleum pretense) are about equally sensitive to ozone, both are equally affected in

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 617 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

Resistance to Air Pollutants: From Cell to Community 617

competition and the ratio in biomass is unaffected. In contrast, because white clover

(T. repens) is more sensitive than its usual companion grasses, it tends to decline in compe-

tition. The primary effect is on the stolons; if O

3

concentrations decrease then plants may

recover, but there can be lasting effects on stolon density (Wilbourn 1991). Figure 20.10

TABLE 20.1

Impact of O

3

on Growth and Root=Shoot Dry Matter Partitioning in 32 Taxa

a

R week

1

K ¼ R

root

=R

shoot

Control þO

3

R% Control þO

3

K%

Arrhenatherum elatius 1.96 1.85 6 0.84 1.01 þ20***

Avena fatua 1.97 2.00 þ2 0.87 0.80 8

Brachypodium pinnatum 1.58 1.48 6 0.75 0.81 þ8*

Bromus erectus 1.93 1.92 0 1.05 1.18 12*

Bromus sterilis 1.77 1.73 2 1.02 1.08 þ6

Cerastium fontanum 2.18 1.96 10*** 0.67 0.65 3

Chenopodium album 1.99 1.97 1 0.62 0.53 14***

Deschampsia flexuosa 1.81 1.73 4 0.95 0.96 þ1

Desmazeria rigida 1.21 1.10 9 1.23 0.75 39**

Epilobium hirsutum 1.61 1.58 2 0.83 0.62 25**

Festuca ovina 1.35 1.27 6 0.58 0.60 þ4

Holcus lanatus 1.64 1.57 4* 0.93 0.91 2

Hordeum murinum 1.84 1.74 5* 0.83 0.79 5

Koeleria macrantha 1.73 1.63 6*** 0.77 0.42 45*

Lolium perenne Talbot 2.03 1.98 2 0.65 0.88 þ35*

Nicotiana tabacum Bel-W3 2.27 1.91 16*** 0.98 0.89 9

Pisum sativum 1.95 1.80 8*** 1.07 1.24 þ

16

Conquest

Plantago coronopus 2.28 1.98 13*** 0.76 0.79 þ4

Plantago lanceolata 2.17 1.98 9** 1.10 0.72 34**

Plantago major

b

1 2.46 1.88 24*** 0.95 0.86 9***

2 2.36 1.81 23** 0.90 0.83 8**

Plantago major Athens 1.79 1.77 1 0.90 0.96 þ7

Plantago maritime 1.76 1.66 6 0.87 0.95 þ9

Plantago media 1.29 1.33 þ3 1.16 1.25 þ8

Poa annua 1.56 1.45 7* 1.03 0.92 11*

Poa trivialis 1.34 1.29 4 0.95 0.89 6

Rumex acetosa 1.72 1.71 1 0.63 0.85 þ35*

Rumex acetosella 1.71 1.54 10* 1.06 1.08 þ2

Rumex obtusifolius 2.16 1.97 9** 0.87 0.83 5

Teucrium scorodomia 0221 1.74 1.56 10** 0.70 0.70 0

Teucrium scorodonia 0223 1.74 1.57 10** 0.84 0.70 17**

Urtica dioica 2.59 2.29 12*** 1.54 1.35 12***

Source: From Reiling, K. and Davison, A.W., New Phytol., 120, 29, 1992.

a

Plants were raised in duplicate controlled environment chambers ventilated with charcoal=Purafil-filtered air

(control; <5 nL L

1

O

3

)orO

3

(70 nL L

1

O

3

for 7 h day

1

for 2 weeks). R, mean plant relative growth rate; K,

allometric root=shoot coefficient; R%, the % change in R; K%, the % change in K. Asterisks denote probability of

difference between control and fumigated plants: *0.05, **0.01, ***0.001. With the exception of pea (Pisum sativum L.

cv. Conquest, supplied by Batchelors foods) and tobacoo (Nicotiana tabacum L. cv. Bel-W3, supplied by IPO,

Wageningen), which were included for comparative purposes, all seeds were supplied by the UCPE seed bank,

Sheffield University, UK.

b

Because of limited space in the fumigation chambers, only five to six taxa could be grown and tested at a time. To

ensure reproducibility, one species (Plantago major) was tested twice—once at the beginning (1) and once at the end

(2) of the series of experiments.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 618 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

618 Functional Plant Ecology

shows the recent collation of data by Fuhrer (1997) from white clover experiments performed

in the United States and Europe. This reveals two important points: (1) there is good

agreement in dose–response relationships between experimental studies, despite difference

in varieties, exposure techniques, and climate and (2) total forage yield tends to be much less

affected than that of the sensitive component (in this case, clover).

The few OTC studies conducted on communities other than grass=clover mixtures indi-

cate that ambient levels of SO

2

and O

3

may already be high enough to modify species

composition in parts of Europe and the United States Working on O

3

, Ashmore and

Ainsworth (1995) found little effect on the total biomass of mixtures of two grasses and

forbs sown as seeds in pots of unamended acid soil, but the forb component declined with

increasing exposure. Similar changes in forbs (Campanula rotundifolia, Leontodon hispidus,

Lotus corniculatus, Sanguisorba minor) were reported by Ashmore et al. (1995) in a simulated

calcareous grassland mixture. Bearing in mind the simplified nature of the community and the

absence of interacting factors such as water deficit, these data provide a tentative indication

that species composition might be affected in parts of central and northern Europe in high-O

3

years. Where pollutant concentrations are variable from year to year, long-term effects would

be expected to depend on the magnitude of the changes in years with high pollutant concen-

trations and the capacity of the community to recover in between. The strongest experimental

evidence that ambient levels of O

3

have a significant ecological impact comes from work

conducted in the United States. Duchelle et al. (1983) determined the effects of ambient O

3

on

the productivity of natural vegetation in a high meadow in the Shenandoah National Park.

Over 3 years, aboveground biomass was increased by filtration and the cumulative dry

weights for charcoalfiltered (CF), nonfiltered (NF), and ambient air (AA) treatments were

significantly different at 1.38, 1.09, and 0:89 kg m

2

, respectively, but data relating to effects

on species richness were not collected. Working in the same area, Barbo et al. (1994, 1998)

exposed an early successional forest community to AA, CF, NF, and 2 AA. They found

changes in species performance, canopy structure, species richness, and diversity index

consistent with the view that oxidants have resulted in a shift in vegetation dominance in

some heavily polluted regions. Comparably large effects have not been reported in Europe,

Total yield

Clover

0.0

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

0.02 0.04

Seasonal mean daytime ozone concentration (µL L

−1

)

Yield relative to control

0.06 0.08 0.1

FIGURE 20.10 Effects of O

3

(seasonal daytime mean) on relative yield and clove content of managed

grassland. (Redrawn from Fuhrer, J., Ecological Advances and Environmental Impact Assessment,

Gulf Publishing Company, Houston, 1997. With permission; based on the regression of four datasets.)

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C020 Final Proof page 619 25.4.2007 5:25pm Compositor Name: DeShanthi

Resistance to Air Pollutants: From Cell to Community 619