Pugnaire F.I. Valladares F. Functional Plant Ecology

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

INTRODUCTION

Antarctica is the coldest, driest, highest and windiest continent, its plants grow where it is warm, wet,

low and calm. Ecophysiologists should be grateful.

Research on terrestrial plants in Antarctica has been most intense for just over four decades.

The International Geophysical Year (IGY 1958, p. 59) led to the establishment of many

national stations in Antarctica and, although research concentrated on the physical sciences,

there was always a proportion of natural science. Progress has, however, certainly been

spasmodic as can be seen in the summary of the history of terrestrial biota research in the

western part of the peninsula (Smith 1996). Initial studies, in the 1950s and 1960s, coincided

with a growth in interest in stress survival mechanisms in organisms and, as a result, there has

been a considerably higher proportion of plant ecophysiological research in Antarctica than

in work on the same groups elsewhere. Taxonomy, to some extent, languished but the

situation has been rectified by the appearance of substantial good reviews on some major

groups and areas, for example, Usnea (Walker 1985), Bryum (Seppelt and Kanda 1986),

Umbilicaria (Filson 1987), Stereocaulon (Smith and O

¨

vstedal 1991), Cladoniaceae (Stenroos

1993), Caloplaca (So

¨

chting and Olech 1995), lichens of the Terra Nova area (Castello 2003),

bryophytes of Southern Victoria Land (Seppelt and Green 1998), together with important

floras for liverworts (Bednarek-Ochyra et al. 2000), lichens (O

¨

vstedal and Smith 2001), and

mosses of King George Island (Ochyra 1998). This improvement of knowledge has resulted in

a better understanding of the geographical relationships of the flora (Castello and Nimis

1995, 1997, Seppelt 1995; Smith 2000, Peat et al. 2007) and the appearance of searchable

online databases such as VICTORIA for the lichens of Victoria Land (Castello et al. 2006),

the online searchable herbarium database of the British Antarctic Survey, and Australian

Antarctic Data Centre (Australian Antarctic Programme).

Despite the mixture of research approaches we are still far from understanding well both

the distribution and functioning of the terrestrial plants and animals. This is certainly a

reflection of the difficulties of working in the region and also of the patchy nature of research

in some national programs. This has now started to be rectified by the development of multi-

disciplinary, long-term research using standardized methodologies, for example: Long Term

Ecological Research site in the Taylor Valley (McMurdo LTER, National Science Foundation,

USA), Evolutionary Biology of Antarctica (EBA, a SCAR initiative), and the Latitudinal

Gradient Project (LGP, Antarctica New Zealand). The first State of the Environment Report

has also appeared for the Ross Sea region (Waterhouse 2001). However, as is true for all

research, new data reveal new puzzles and new questions and, as a result, ideas about the

vegetation in Antarctica now appear to be in a greater state of flux than a decade ago.

In this chapter we try to bring out the major features of the ecophysiology of terrestrial

plants in Antarctica with some emphasis on what appears to be controlling the distribution

and performance. We do this by linking information about distribution and abundance with

knowledge of the ecophysiological performance including growth rates, and by considering

whether the plants show special adaptations to the Antarctic environment. This knowledge is

of growing importance because of the needs to both conserve and manage the communities

as well as the suggested potential to use the vegetation to detect global change processes such

as climate warming (Kennedy 1995). Several excellent review articles exist that can provide

more detail about specific plant groups or locations (Holdgate 1964, 1977, Ahmadjian 1970,

Smith 1984, 1996, 2000, Longton 1988a,b, Kappen 1988, 1993a, Vincent 1988). Some recent

reviews and literature compilations have addressed the possible effects of global climate

change in Antarctica (Robinson et al. 2003, Frenot et al. 2004, Barnes et al. 2006). A history of

botanical exploration has also been published (Senchina 2005) and a comprehensive study

of contaminants of the vegetation has been prepared (Bargagli 2005).

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 390 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

390 Functional Plant Ecology

DEFINITIONS

In this chapter, plants are defined to include higher plants (only two angiosperm species

occur), all bryophytes (predominantly mosses since liverworts are rare south of about 708 S

latitude), and lichens. The latter, associations between fungi as host and algae or cyano-

bacteria as symbionts, are nowadays correctly referred to as the fungi; however, their

prominent role in Antarctica and their phototrophic lifestyle supports the tradition of

including them as members of the terrestrial vegetation. The algae and cyanobacteria,

which are also common in wet, terrestrial sites (Vincent 1988), are not covered except when

in symbiotic association in a lichen.

Antarctica includes the main Antarctic continent (continental Antarctica), the Antarctic

Peninsula, and its closely associated islands to the west and north (South Shetland Islands,

South Orkney Islands). Subantarctic islands are not included.

CLIMATE ZONES

Antarctica spans a large latitudinal range of around 278 latitude from the north of the

peninsula (638 S) to the pole and an associated large climate range. It is certainly true to

say that Antarctica is the coldest, windiest, driest, and highest continent, the latter feature

contributing to the very low inland temperatures (Table 13.1). Several authors have produced

subdivisions based on the climate and these are summarized in Smith (1996). There is general

agreement that two zones can be separated reflecting both climate and vegetation. The first is

the maritime Antarctic (Holdgate 1964) or cold–polar zone of Longton (1988a,b). This

comprises the Antarctic Peninsula: west side north of c.708 S (from southern Marguerite

Bay) and offshore islands (including northern Alexander I.), north-eastern side north of c.648 S;

South Shetland Is, South Orkney Is., South Sandwich I., Bouvetøya. The zone is charac-

terized by warmest months with mean temperatures above freezing point (0–28C) and mean

winter temperatures rarely less than 108C (see data for Faraday Station and Bellingshausen

Station in Table 13.1). Precipitation, which occurs as rain in summer, is between 350 and 750 mm

TABLE 13.1

Climatic Information for Various Locations in the Maritime Zone, Continental Zone,

and Polar Plateau in Antarctica

Location

Mean Temperature

Warmest Month

Mean Temperature

Coldest Month

Precipitation

(mm Rain Equivalent)

Maritime

South Shetland Islands

(Bellingshausen) (628 12

0

S)

þ1.6 6.4 729

North-west Peninsula

(Faraday) (63–698 S)

þ0.7 9.4 380–500

Continent

Casey (668 17

0

S) þ0.1 14.8 330

Syowa (698 00

0

S) 0.7 19.4 250

Mawson (678 26

0

S) 0.1 18.6 100

Davis (688 35

0

S) þ0.9 17.5 350

Cape Hallett (728 19

0

S) 1.4 26.6 225

Taylor Valley (778 35

0

S) þ1.0 39.3 10 (floor)

50 (mountains)

Scott Base (778 51

0

S) 4.8 26.3 130

Polar Plateau

Dome Fuji (778 31

0

S) (altitude 3810 m) 26.1 67.8 100

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 391 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

Plant Life in Antarctica 391

(rain equivalent) and the area is, essentially, an oceanic cold tundra. The climate is

controlled by the strong westerly, maritime influences, and is markedly different from the

eastern side of the peninsula. The vegetation includes the only two Antarctic angiosperms

(Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth.)) Bartl. and Deschampsia antarctica Desv., and substantial

numbers of lichens and bryophytes (around 350 and 100 species, respectively) including

around 27 species of liverworts (Peat et al. 2007). Analysis of published collections and

herbarium records suggests that the Antarctic Peninsula could be validly subdivided into

two parts that better reflect the species present (Peat et al. 2007). The suggested zones are the

northwestern Peninsula including adjacent islands, and the southern and eastern Peninsula.

This new subdivision appears to be a better representation of the vegetation and is used in the

remainder of this chapter.

The remaining zone is continental Antarctic (Holdgate 1964) or frigid Antarctic of Longton

(1988a,b). Geographically this includes the whole of the main Antarctic continent, the east

of the Antarctic peninsula and the west of the peninsula as far north as, and including,

southern Alexander Island; it is approximately delineated as south of the Antarctic polar

circle (Figure 13.1). The zone is characterized by the mean temperature of the warmest

month, which is below freezing point, often substantially below it (Table 13.1). The mean

winter temperatures are much lower than in the maritime Antarctic as they are typically

around 208C or below (Table 13.1). Temperatures, wind, and precipitation are all governed

by the circumpolar vortex. The circular shape of the continent encourages cyclones to circle

rather than moving onto it. Entry of maritime weather systems is also discouraged by the

height of the polar plateau, which is predominantly above 2000 m. Precipitation, 300 mm

(rain equivalent) as snow, occurs mainly in the coastal belt and the net result is growing

aridity with increase in latitude so that annual precipitation can be very low, around 120 mm

(rain equivalent) at McMurdo (778 51

0

S) and 50 mm near the pole (Table 13.1). Precipitation

shadows can lead to even lower, local values such as the 225 mm at Cape Hallett (728 19

0

S)

and the extreme 10–50 mm in the Dry Valley region (around 778 00

0

–778 50

0

S). Cold air

descending from the polar plateau causes strong katabatic winds at the continent margins

Livingston

island

Faraday

station

Maritime

boundary

Antarctic

Peninsula

Mt. Kyffin

Ross island,

dry valleys

Cape

Hallett

Ross

Sea region

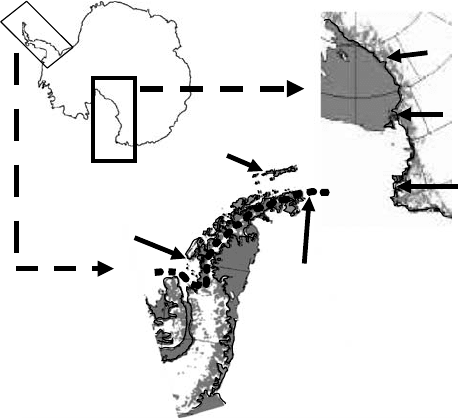

FIGURE 13.1 Map of Antarctica, with insets of the Antarctic Peninsula and the Ross Sea areas,

showing the division into maritime and Continental zones, with the boundary most clearly seen in the

Peninsula insert map. The named locations are referred to in the text or in the tables.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 392 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

392 Functional Plant Ecology

making some areas exceptionally windy (e.g., Cape Denison, mean wind speed of 24:9ms

1

for July 1913, in Mawson, The Home of the Blizzard). The vegetation in this zone is

composed entirely of lichens and mosses with the rare occurrence of one species of liverwort

[Cephaloziella exiliflora (Tayl.) Steph.]. The vegetation is confined to ice-free areas of

varying size. There are around 20, so-called oases (Pickard 1986), and even in those the

vegetation is very scattered and only locally abundant, as it is dependent on moisture supply,

warmth, and protection from the wind. Lichens and mosses have been reported from as far

south as 868 30’’ S and 848 S, respectively (Wise and Gressit 1965, Claridge et al. 1971, Broady

and Weinstein 1998), and, although some represent isolated occurrences there is evidence of

unexpected biodiversity at high latitudes (Cawley and Tyndale-Biscoe 1960, Tuerk et al.

2004). Desiccation over winter becomes very important in this zone and plants are not only

frozen but can become completely freeze-dried as temperatures reach 508C at low ambient

humidity.

VEGETATION TRENDS

B

IODIVERSITY

There is a marked decline in biodiversity with increase in latitude; however, it is not linear but

shows disjunctions. The number of species of all groups is at their highest in the northern

maritime zone with about 350 species of lichen, 100–115 mosses, 27 liverworts, and 2 higher

plants (Table 13.2). There is a sharp decline in lichens and mosses to about a third of these

levels and in liverworts to about one-tenth. The continental Antarctic has no phanerogams; it

has only one liverwort and about 20% of the number of lichen and moss species. However, it

should be noted that no more than around 30–40 species of lichens are found at any particular

location (Table 13.2). The two higher plants are confined to the Antarctic Peninsula and reach

their absolute southern limit at 688 43

0

S. Over the past 40 years there has been evidence of

local population increase in line with a warming climate trend in the region (Smith 1994, Day

et al. 1999). Neither of the two species occurs in the continental Antarctic. All the remaining

components of the vegetation are poikilohydric but show difference in their distribution that

appears to reflect water availability rather than temperature (although desiccation and cold

resistance are tightly linked). The liverworts have less resistance to desiccation than mosses

and are only of significance in the north-western Peninsula (the maritime zone). Their

presence elsewhere must indicate exceptional local conditions such as the occurrence on

heated soil on Mt Melbourne (Broady et al. 1987). The mosses show a distinct decline

along the Peninsula and only about 20 species are found in the continent. Their southernmost

records are close to those of lichens at around 848 S. Outside the northern Peninsula, the

vegetation is dominated by lichens with around 100 species still present in continental

Antarctica. Some less obvious trends exist, such as lichens with cyanobacterial photobionts

confined to the maritime Antarctic (Kappen 1993a, Schroeter et al. 1994) and a general

increase in the proportion of crustose lichen species as conditions become more severe

(Kappen 1988). Kappen (1988) refers to a group of 13 circumpolar lichen species that tend

to occur around the continent with other species occurring only locally.

Although about 100 species of lichens are found on the main continent, it is interesting

that only about 30–40 species are found at any particular location (Table 13.2). Although a

cline in lichen biodiversity occurs in the Peninsula, it appears that this is not true for the main

continent. Distributions in the Ross Sea region confirm this with the richest site being

Edmonson Point, Central Victoria Land but with about 27 species still present at Mt Kyffin,

848 S. A more detailed analysis revealed that there was only between 20% and 35% similarity

in species between sites in the Ross Sea. Essentially each site has a different sampling of about

100 species that occur in the region and only around 4 species are common to all sites

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 393 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

Plant Life in Antarctica 393

(Acarospora gwynii, Buellia frigida, Umbilicaria aprina, and a Lecidea species. This is a

complete contrast to the Peninsula where there is a gradual loss of species with increase in

latitude. One contributor to this situation is the loss of species south of Ross Island, which are

usually taken as indicating enrichment by birds (Caloplaca species, Candelariella species,

Physcia caesia, Physcia dubia, Xanthoria elegans, and Xanthoria mawsonii). This indicates a

blocking of marine influence in the southern Ross Sea where the Ross Ice Shelf is present.

A second possible explanation is that conditions have become so dry in the continent and the

Ross Sea region that lichens are confined to sporadic microsites with suitable climates and

that it is a lottery as to which species can effect the initial colonization.

BIOMASS

Biomass data from a range of Antarctic locations are given in Table 13.2. Within continental

Antarctica there is a remarkable agreement between the maximal biomasses from most sites

when expressed as 100% cover. A typical maximal value of around 1000---1500 g m

2

is found

both for lichens and mosses. Kappen (1993a) gives a data summary showing that such

TABLE 13.2

Numbers of Species of Flowering Plants, Lichens, Mosses, and Liverworts, Community

Types, Maximal Biomass, and Presence of Peat at Various Locations in the Maritime

and Continental Antarctica

Location

Flowering

Plants Lichens Mosses Liverworts

Community

Types

Maximal

Biomass

(g m

2

) Peat

Maritime

North-west

peninsula

65–688 S

2 c.350 100–115 27 1.1; 1.2; 1.3;

1.4; 1.5; 1.6; 2.1

1,000–46,000 1.5 m

Southern

peninsula

68–728 S

2 c.120 40–50 2 1.1; 1.2; 1.3; 2.1 ? 0

Continental

Mawson 678 26

0

S 0 9 2 0 1.1; 1.2; 1.3 <1100 0

Davis 688 35

0

S 0 34 6 1 1.1; 1.2; 1.3 ? 0

Casey 668 17

0

S 0 35 5 1 1.1; 1.2; 1.3 900 0

Birthday Ridge

708 48

0

S

0 33 5 0 1.1; 1.2; 1.3 50–950 0

Botany Bay

a

778 00

0

S

0 34 8 1 1.1; 1.2; 1.3 >1000 0

Dry Valleys

a

778 45

0

S

0 30 7 0 1.1; 1.3 ? 0

Mt Kyffin

a

848 45

0

S

0 27 2 0 1.1; 1.2; 1.3 ? 0

Sources: Communities (Crustaceous and foliose lichen sub-formation (1.1), Fruticose and foliose lichen sub-

formation (1.2), Short moss cushion and turf sub-formation (1.3), Tall moss turf sub-formation (1.4), Tall

moss cushion sub-formation (1.5), Bryophyte carpet and mat sub-formation (1.6), Grass and cushion chaemophyte

sub-formation (2.1), are from Smith, R.I.L., Foundations for Ecological Research West of the Antarctic Peninsula,

Koss, R.M., Hofmann, E., and Quetin, L.B., eds, Antarctic Research Series, Volume 70, American Geophysical

Union, Washington, 1996). Definition of maritime zones and numbers of species are from Peat, H.J., Clarke, A., and

Convey, P., J. Biogeo., 34, 132, 2007.

a

Species numbers from data of authors collected during LGP research.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 394 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

394 Functional Plant Ecology

maximal biomasses occur for lichens from Victoria Land (708 S) to King George Island

(South Shetland islands) and Signy Island in the northern maritime Antarctic (61–628 S). This

seems to be the maximal biomass for this thin, almost two-dimensional vegetation. In the

maritime there can be extensive peat build-up to depths of 50 cm or more leading to greatly

increased values, to 46,000 g m

2

in some cases under Chorisodontium aciphyllum (Hook f. et

Wils.) Broth. and Polytrichum alpestre Hoppe. The age of such peat banks is still uncertain

but some have been carbon dated to 5350 years in the South Orkney Islands (Bjork et al.

1991). Biomass is about 10,000 g m

2

, in the 20 cm deep layer above the permafrost. A value

of 300---1000 g m

2

is given by Longton (1988a) for the green, photosynthetic shoots, a

number similar to that for maximal biomass without peat production. It is difficult to explain

the lack of peat production in the continental Antarctic where, due to the colder temperat-

ures, decomposition processes would be expected to be even slower (Collins 1976, Davis 1980,

1986); however, it could simply reflect much lower production rates.

The data must be treated with considerable caution since they are often adjusted to 100%

cover equivalence and, even if this is not done, they only normally apply to where the plants

are present and not to the overall ice-free area. The data are, therefore, unrepresentative since

vegetation occurrence is sporadic. Kennedy (1993b) has calculated that, in Ablation Valley

on Alexander Island, terrestrial vegetation is confined almost entirely to seven, discrete

patches totaling 2300 m

2

in a total ice-free area of 400,000 m

2

(Light and Heywood 1975).

Similarly, the rich Canada Glacier flush totaling some 10,000 m

2

is the only extensive patch of

vegetation in an ice-free area of 25,000,000 m

2

(Schwarz et al. 1992). In many ways the

situation is similar to describing the vegetation of the Sahara Desert by extrapolation from

surveys at oases. It is unfortunate that the focusing of scientific attention on the plants

disguises their relative rarity, if a typical area had to be preserved in ice-free areas it would

be almost entirely bare ground. This would not be inappropriate because recent studies

have shown this apparently barren ground to have substantial microbial biomasses (Cowan

et al. 2001, Cowan and Tow 2004).

COMMUNITY STRUCTURE

There have been several detailed accounts of vegetation and community structure in the

Antarctic (see Longton 1988a,b, Smith 1996) and only the major trends are considered here.

The plant association confined to the maritime is that dominated by higher plants, the grass,

and cushion chaemophyte sub-formation. Although the two phanerogams can be found

occasionally in other formations, their best development occurs on moist to dry soil especially

in sheltered, north-facing coastal habitats where closed swards can sometimes develop.

Subdivisions of cryptogamic communities, here from Smith (1996), depend on whether

lichens or bryophytes (mosses) are dominant. In the bryophyte carpet and mat sub-formation

(pleurocarpous mosses and liverworts on wet ground), lichens are sparse or absent, in the

tall moss cushion sub-formation (tall moss cushions and some deep carpet forms along

melt-stream courses) and in the tall moss turf sub-formation (predominantly Polytrichum–

Chorisodontium species), fruticose lichens of the genera Stereocaulon, Cladonia, and Sphaer-

ophorus are also very common. These formations are only found in the maritime zone. They

are much more luxuriant and rich than communities in continental Antarctica where the

predominant association is the short moss cushion and turf sub-formation (mainly a Bryum–

Ceratodon–Pottia association) occurs. Overall the bryophytes become shorter, less able to

develop continuous stands and form less extensive patches (Table 13.2). Location becomes

ever more important and mosses are confined to highly protected sites where regular melt-

water can occur such as cracks in rocks, adjacent to permanent snow banks and in areas with

running water usually close to glaciers or in depressions. In some areas the shoots are

restricted to just below or at the surface of the substrate.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 395 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

Plant Life in Antarctica 395

Lichen communities show similar trends. In the maritime zone there are extensive areas

where fruticose lichens are dominant, the fruticose and foliose lichen formation, typically

on the sides of rocks or boulders forming marine benches or similar areas (Figure 13.2).

This distribution seems to be determined by improved water relations and it is easy to see

how snow gathers in such areas, how wind is reduced and how light is high but rarely direct

sunlight. Such sites are well illustrated in Kappen (1993a). The genera Usnea (Figure 13.3)

and Umbilicaria are typically dominant and plants can reach large sizes, 20 þcm across

for Umbilicaria specimens. These formations are rarer in the continental zone but do occur,

for example, Birthday Ridge (Kappen 1985a) and Botany Bay, Granite Harbour (unpub-

lished, in preparation). The second lichen formation, crustaceous and foliose lichens,is

extensive in both the maritime and continental Antarctic and is the only association on

bare rock faces. It is the predominant formation in the continental zone and can form

anywhere where there is protection and supply of water either as melt or blown snow.

However, there are also considerable limitations to its presence and the lichens are often

confined to a particular rock face or to crevices depending on wind, light, and snow

occurrence (Figure 13.3). It is a patchy formation and rarely is 100% cover approached,

more typically the cover is very low. Crustaceous species become almost the only lichens

under the more extreme conditions and, under dry conditions but with a water supply and

light, the endolithic association appears (Friedmann 1982). In the mountains of the Dry

Valley region this is the most common community but it is present over almost the entire

continent where other growth forms cannot occur. In both the maritime and continental

zones the occurrence of some species is strongly dependent on a rich nutrient supply from

perching birds (Olech 1990).

Overall there is a clear trend for smaller plants, lower biodiversity, and greater confine-

ment to protected sites as latitude increases (Table 13.2). Where there is a coincidence of

shelter, warmth, light, and reliable water supply, rich communities can develop at high

latitudes. A good example is the exceptional community at Botany Bay, Granite Harbour

which, even though at 778 S, is richer than almost all other continental sites and even has the

liverwort C. exiliflora present (Seppelt and Green 1998). The occurrence of this one species

FIGURE 13.2 Photograph of a rich Fruticose and Foliose Lichen sub-formation (1.2 in Smith 1996) at

Livingston Island in the maritime Antarctic. The most visible lichens are specimens of the fruticose

genus Usnea.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 396 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

396 Functional Plant Ecology

would suggest that the site has summer months with mean temperatures close to or above

freezing although no data are available to test this hypothesis at present.

PLANT PERFORMANCE: CO

2

-EXCHANGE

Higher plants are considered only briefly because they are confined to the maritime

Antarctic. The majority of the studies have been on lichens and bryophytes, which dominate

most communities. In the case of the bryophytes, the mosses are clearly the major group;

liverworts are not significant in continental Antarctica and are only locally common in the

maritime zone; unfortunately, they have been little studied. Plant performance has mostly been

studied as photosynthetic activity measured mainly as CO

2

exchange in the field or on samples

returned to laboratories. CO

2

exchange is reported as net photosynthesis (NP), dark respiration

(DR), photorespiration (PR), and gross photosynthesis (GP calculated as NP þDR). There

is a growing use of chlorophyll a fluorescence techniques but these have some important

limitations; in particular they are not a reliable indicator of CO

2

exchange.

FIGURE 13.3 Upper photograph: Lichen community at Botany Bay, Granite Harbour showing the well

developed Umbilicaria aprina thalli in the water fall area and the surrounding crustose species. Lower

phtograph: U. aprina thalli in a crack in granite in Lower Taylor Valley showing the formation of a

suitable microclimate by water gathering in the rock crack.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 397 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

Plant Life in Antarctica 397

CO

2

-EXCHANGE RESPONSE TO MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL AND PLANT FACTORS

Higher Plants

The ecophysiology of C. quitensis and D. antarctica has been reviewed by Alberdi et al. (2002)

although the plants have not been extensively studied. No morphological adaptations specifi-

cally for Antarctica were found. Both species tend to be xeromorphic, which is almost

certainly a response to the generally cold environment, especially the soils. D. antarctica has

a high water use efficiency, about 60---120 mol H

2

O mol

1

CO

2

fixed compared with values of

300–500 for normal C

3

plants (Montiel et al. 1999). Apart from conserving water this might

also be expected to raise leaf temperatures due to lowered transpirational cooling. Plants

studied in the laboratory were found to have optimal temperatures for NP of 138C for C.

quitensis and 198C for D. antarctica. Both species retained NP of about 30% of maximal rate

at 08C and it is suggested that this ability is the reason for their success in the maritime

Antarctic (Edwards and Smith 1988). Light levels for saturation were low, 30 mmol m

2

s

1

PPFD (Photosynthetic Photon Flux density) at 08C and 150 mmol m

2

s

1

PPFD at 108C,

indicating shade-adapted plants. This could also be considered as acclimation for the gener-

ally cloudy conditions in this area. Both plants show little photoinhibition and seem to be well

adapted to natural radiation and UV-B levels. Some studies have shown improved growth

when incident UV-B was reduced but this is most likely a secondary effect rather than a direct

impact of the UV radiation (Day et al. 1999). Overall, Edwards and Smith (1988) suggested

that the plants showed no particular special adaptation for growth in Antarctica and Convey

(1996) suggests that their presence could be a matter of chance. However, when it is

considered how long there has been contact between South America and the maritime Antarctic

without strong quarantine controls until recently, with only minor new introductions, also

how extensive the range is of these two plants, then perhaps they do have some special

property or properties that are yet to be identified. Fowbert and Smith (1994) demonstrated

that the populations are increasing and have been doing so since the 1940s, an increase that is

suggested to reflect higher summer temperatures in the area (Smith 1994).

Liverworts

The few studies on liverworts have provided some interesting insights into their poor

performance in Antarctica. Marchantia berteroana Lehm. et Lindenb., studied in Signy Island,

was extremely sensitive to both desiccation and low temperatures (Davey 1997a). Photosyn-

thesis was only 16% of original rate at 108C after 24 h at 58C and there was no activity at all

after 24 h at 258C. Five freeze=thaw cycles to 58C caused NP to fall to around 3% of

original value. The plants required a high water content of 10 g g(d:wt:)

1

(1000%) for

maximal GP and desiccation for 1–6 months led to an almost complete loss of photosynthetic

ability. However, in the field the plants were always found to be fully hydrated and never

suffered desiccation. Maximal GP and NP were slightly higher than the published values for a

related species Marchantia foliacea Mitt., in New Zealand (Green and Snelgar 1982).

C. exiliflora, the only liverwort to grow in continental Antarctica, loses its typical purple color

in shaded areas and the pigment probably functioned as a form of light protection (Post and

Vesk 1992). This agrees with studies showing rapid adjustment of UV-B filtering compounds

to incident UV-B (Newsham 2002). Green plants, without the pigment, had lower light

compensation and saturation values and a greater apparent quantum efficiency (Post and

Vesk 1992). These features, together with the similar Chl a=Chl b ratios in the two forms are

typical for bryophytes utilizing some form of light filter (Green and Lange 1994). Maximal

GP, 100 mmol O

2

(mg Chl)

1

h

1

, was similar to those of other bryophytes. Unfortunately

there were no studies of low temperature tolerance but the distribution of the plant suggests

that this will not be high.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 398 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

398 Functional Plant Ecology

Mosses

Mosses show a normal saturation response to PPFD but there is contrasting evidence of

adaptation to incident light. Some early studies suggested low compensation and saturation

PPFD (Rastorfer 1970, 1972) with saturation at around 15% of full sunlight (about

300 mmol m

2

s

1

Longton 1988a). However, recent studies with measurements made in

the field suggest that saturation may not occur even at full sunlight under some conditions

(Figure 13.4). Bryum subrotundifolium can show a range of forms depending on the light

climate of its environment and also change rapidly between forms (Green et al. 2000). Post

(1990) found a similar situation with ginger and green forms of Ceratodon purpureus (Hedw.)

Brid. Although these seem to be similar to the sun=shade adaptations of higher plant leaves,

they represent a different form of response. In contrast to higher plants the sun forms can

have both lower maximal NP and lower apparent quantum efficiency (Green et al. 2000). It

appears that adaptation to high light is by putting filters in place, so that they are protected

shade forms, rather than by acclimation of the photosynthetic apparatus. There is little

evidence that photoinhibition occurs when the plants are in their natural habitat (Schlensog

et al. 2003). The ability to rapidly change form suggests that measurements made in the

laboratory may not be representative of the field situation.

Net photosynthetic response to temperature shows an optimum (Topt) between 58Cand

258C (Longton 1988a). Topt appears to be variable between species and even within the same

species at different times (Pannewitz et al. 2005). Topt for C. purpureus was around 6.58Cat

Granite Harbour (778 S) in 2000 and 2001, whereas that of Bryum pseudotriquetrum changed

from 9.18C to 15.98C. Smith (1999) found Topt for three species, C. purpureus, B. pseudo-

triquetrum, and Bryum argenteum, at Edmonson Point (748 S) to all be around 158C. At

present the high variability makes it difficult to find any trends with latitude. Topt for NP

depends strongly on PPFD and is lower at PPFD below saturation (Rastorfer 1970, Pannewitz

et al. 2005). At temperatures below Topt, NP declines due to limitation by low temperature

and excess light energy is handled by increased nonphotosynthetic quench mechanisms

(Green et al. 1998). Above Topt, the depression has always been explained as that due to

increased DR since that rises almost exponentially with increase in temperature, however,

0

10

20

30

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

1800

2000

GP

(µmol CO

2

m

−

2

s

−1

)

PPFD

(µmol m

−2

s

−1

)

c

a

(ppm)

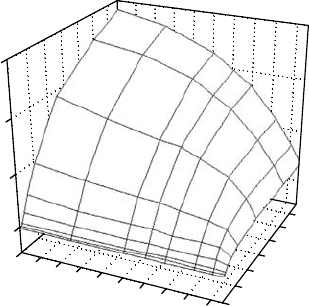

FIGURE 13.4 Response of gross photosynthesis (net photosynthesis plus dark respiration, vertical axis)

of the moss Bryum pseudotriquetrum to light (right axis, PPFD in mmol Photons m

2

s

1

) and carbon

dioxide concentration (front axis in ppm—parts per million) at 208C. There is no saturation by light up

to 1200 mmol m

2

s

1

at all CO

2

concentrations of ambient and above.

Francisco Pugnaire/Functional Plant Ecology 7488_C013 Final Proof page 399 16.4.2007 2:34pm Compositor Name: BMani

Plant Life in Antarctica 399