Principles of Finance with Excel (Основы финансов c Excel)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation page 22

A simple example: Using the price/earnings (P/E) ratio for valuation

The price/earnings ratio is the ratio of a firm’s stock price to its earnings per share:

/

stock price

PE

earnings per share

= .

When we use the P/E for valuation, we assume that similar firms should have similar P/E ratios.

Here’s an example: Shoes for Less (SFL) and Lesser Shoes (LS) are both shoe stores

located in similar communities. Although SFL is bigger than LS, having double the sales and

double the profits, the companies are in most relevant respects similar—management, financial

structure, etc. However, the market valuation of the two companies does not reflect their

similarity: The P/E ratio of SFL is significantly lower than that of LS, as can be seen in the

spreadsheet below:

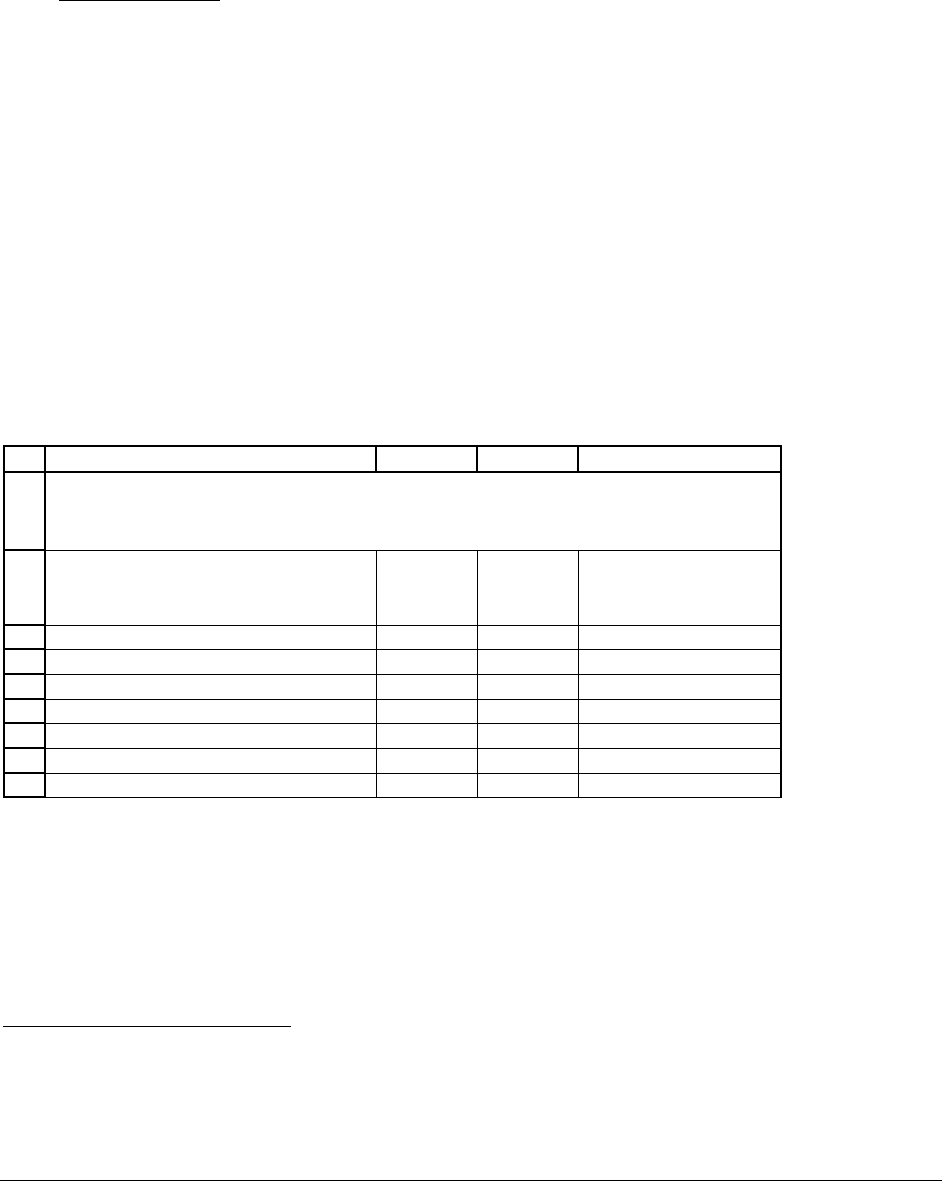

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

ABCD

SFL:

Shoes

for Less

LS:

Lesser

Shoes

Sales

30,000 15,000

Profits

3,000 1,500

Number of shares

1,000 1,000

Shareprice

24 18

Equity value

24,000 18,000 <-- =C6*C5

EPS: Earnings per share

3 1.5 <-- =C4/C5

P/E: Price-Earnings ratio

8.00 12.00 <-- =C6/C8

SHOES FOR LESS (SFL) AND LESSER SHOES (LS)

comparing P/E ratios

Based on the similarity between the two companies, SFL appears underpriced relative to

LS—its P/E ratio is less. A market analyst might recommend that anyone interest in investing in

the shoe store business invest in SFL rather than LS.

3

3

A more radical strategy might be to buy shares of SFL and to short shares of LS. See Chapter 10 and its discussion

of Palm and 3Com shares for a discussion of this strategy.

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation page 23

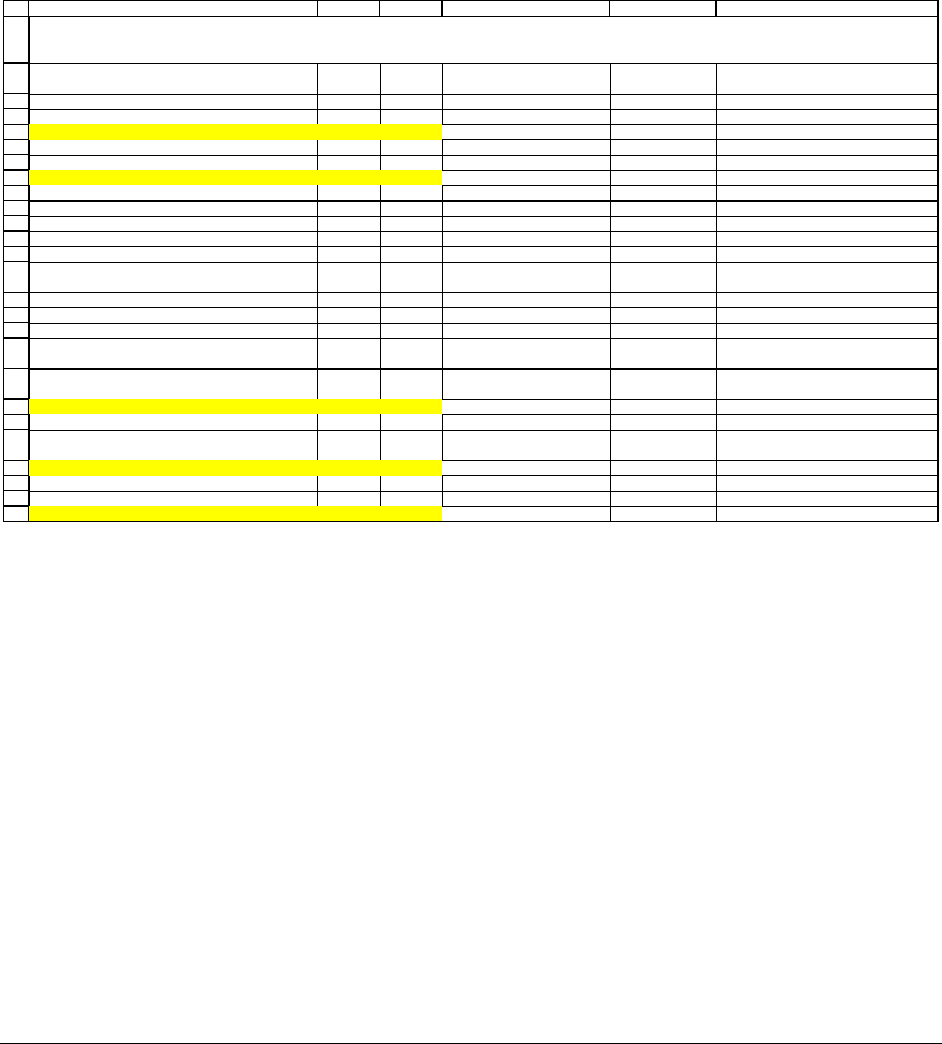

Kroger (KR) and Safeway (SWY)

Here’s a slightly more involved example. The next page gives the Yahoo profiles for

these companies, both of which are in the supermarket business. Some of the data from these

profiles is in the spreadsheet below, which shows 5 multiples for these two firms.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

ABCDEF

KR SWY

Who's more

highly valued?

Stock price 18.09 26.91 <-- Yahoo

Earnings per share (EPS) 1.37 2.60 <-- Yahoo

Price/Earnings (P/E) ratio 13.20 10.35 <-- =C3/C4 Kroger <-- =IF(B5>C5,"Kroger","Safeway")

Book value of equity per share 4.79 11.41 <-- Yahoo

Equity market to book ratio 3.78 2.36 <-- =C3/C7 Kroger <-- =IF(B8>C8,"Kroger","Safeway")

Number of shares outstanding (million) 788.8 466.5 <-- Yahoo

Market value of equity (billion) 14.27 12.55 <-- =C10*C3/1000

Debt/Equity (based on book values) 2.22 1.32 <-- Yahoo

Debt (billion)

this number is not in Yahoo

8.39 7.03 <-- =C10*C7*C13/1000

Cash (billion)

0.185 0.051 <-- Yahoo

Net debt

8.20 6.98 <-- =C14-C15

Book value of equity + debt (billion) - cash

(book value of enterprise)

11.98 12.30 <-- =C10*C7/1000+C14-C15

Market value of equity + debt (billion) - cash

(market value of enterprise)

22.47 19.53 <-- =C11+C14-C15

Enterprise value, market to book 1.88 1.59 <-- =C19/C18 Kroger <-- =IF(B20>C20,"Kroger","Safeway")

Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation

and amortization (EBITDA) in billion$

3.53 2.64 <-- Yahoo

Market enterprise value to EBITDA 6.37 7.40 <-- =C19/C22 Safeway <-- =IF(B23>C23,"Kroger","Safeway")

Sales 50.7 34.7 <-- Yahoo

Market enterprise value to Sales 0.44 0.56 <-- Yahoo Safeway <-- =IF(B26>C26,"Kroger","Safeway")

SAFEWAY (SWY) AND KROGER (KR)--COMPARISON BASED ON MULTIPLES

Based on Yahoo Profiles, 12 September 2002

•

Price/Earnings ratio: This is the most common multiple used. Based on this ratio of

the stock price to the earnings per share (EPS), KR is more highly valued than SWY.

The problem with using this multiple is that it is influenced by many factors, including

the firm’s leverage. We prefer enterprise value ratios such as ….

•

Equity market to book ratio: This is the ratio of the market value of the firm’s equity

to the book value (its accounting value). If the book value accurately measures the cost

of the assets, then a higher equity market to book reflects a greater valuation of the

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation page 24

equity. However, the accounting numbers are heavily influenced by the age of the assets,

the depreciation and other accounting policies, so that this ratio is not so accurate.

•

Enterprise market to book ratio: The enterprise value is the value of the firm’s equity

plus its net debt (defined as book value of debt minus cash). Row 18 above measures the

firm’s net debt by subtracting the cash balances from the book value of the debt. The

enterprise market to book ratio shows that Kroger is valued more highly than Safeway.

•

Market enterprise value to EBITDA: Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and

amortization (EBITDA) is a popular Wall Street measure of the ability of a firm to

produce cash. In spirit it is similar to the free cash flow concept discussed in this chapter,

though it ignores changes in net working capital and capital expenditures. The market

enterprise value to EBITDA ratio shows that Safeway is actually more highly valued than

Kroger.

•

Market enterprise value to Sales ratio: This one of the many other ratios we could use

to compare these two firms. As a percentage of its sales, Safeway is more highly valued

than Kroger; this perhaps reflects Safeway’s ability to extract more cash for its

shareholders from each dollar of sales. Or perhaps it reflects greater shareholder

optimism about the future sales growth rate.

Using multiples to value firms—summary

The multiple method of valuation is a highly effective way of comparing the values of

several companies, as long as the companies being compared are truly comparable.

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation page 25

Comparability is complicated, however, and you should be careful: Truly comparable firms will

have similar operational characteristics such as sales, costs, etc. and also similar financing.

4

4

We’re getting ahead of ourselves, as we did in the previous footnote. The point is that it doesn’t make sense to

compare the stock price of two operationally similar firms if one is financed with a lot of debt and the other firm is

financed primarily with equity. This point is a result of the discussion in Chapters 18-19. For more details see

Chapter 10 of Corporate Finance: A Valuation Approach by Simon Benninga and Oded Sarig (McGraw-Hill 1997).

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation page 26

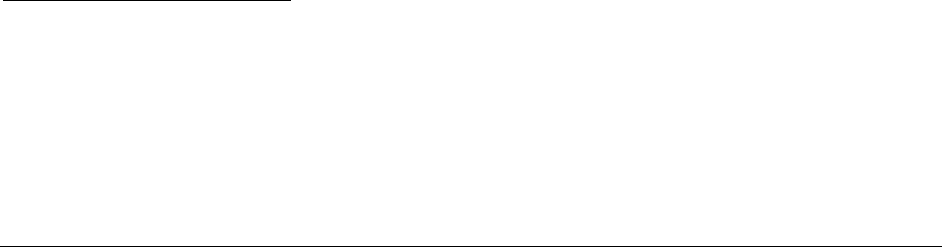

Figure 19.4: Yahoo profiles for Kroger and Safeway. These profiles form the basis for the

multiple valuation illustrated in Section 19.4

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation page 27

The Economist November 24th 2001

Economics focus Taking the measure

Apart from “animal spirits”, what figures excite stockmarket bulls?

AFTER shares worldwide hit their post-

attack lows on September 21st, the Dow

Jones Industrial Average has risen by close

to 20%—in what some enthusiasts already

call a new bull market. Given dismal

forecasts of American growth, plunging

consumer confidence and slashed estimates

for corporate profits, can any of the tools

that are used to measure the markets

validate the bulls?

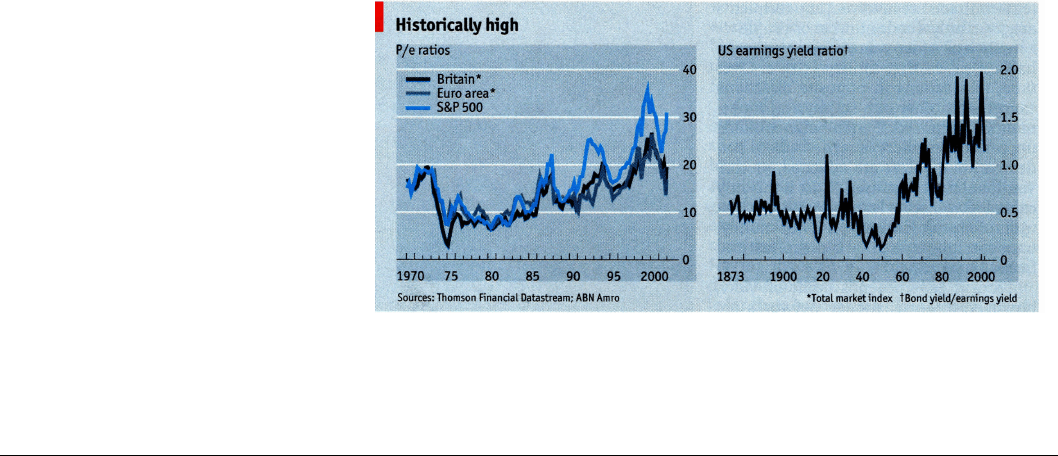

• P/e ratios. One common indicator the

bulls seem to have forgotten, at least in

America, is the price/earnings (p/e) ratio:

the share price divided by earnings per

share. Even when the S&P 500 index hit a

three-year low just after the terrorist attacks,

the average p/e ratio, at 28, was already

high by historical standards; now it stands at

31. In Japan, the average p/e is around 62—

which, hard to believe, is modest compared

with the mid-1990s, when analysts

attempted to justify p/es of over 100. In

Europe, p/e ratios are now blushingly

modest; they average around 16, more

comfortably within historic ranges (see left-

hand chart).

Adding to questions about high

valuations in America is uncertainty over

the “e” in the p/e ratio, the earnings that un-

derpin share valuations. Earlier this month,

Standard & Poor’s, a ratings agency,

complained that too many companies

artificially boost their profits. A recent study

by the Levy Institute estimates that

operating profits for the S&P 500 have been

inflated by at least 10% a year over the past

two decades, thanks to a mix of one-time

write-offs and other accounting tricks. Such

sleights of hand mean that American shares

may be even dearer than they look.

• Yield ratios. As soaring p/e ratios have

become harder to justify in recent years, and

questions about earnings have mounted,

other indicators have come into fashion.

One is the “earnings yield ratio”, which

compares returns on government bonds with

an implicit earnings “yield” (in fact, the

inverse of the p/e ratio) to shareholders. The

theory behind this ratio, popularised by

Alan Greenspan, the Fed chairman, some

years ago, is that the earnings yield on

shares has moved fairly closely in line with

yields on government bonds, at least

recently. In late September, plenty of

analysts pointed to this rule of thumb as an

argument that American shares were cheap.

As a relative measure, the earnings yield

ratio has the virtue of comparing shares with

a riskless alternative, but it is a long way

from being an iron law. As Chris Johns of

ABN Amro, an investment bank, points out,

the relationship between bond yields and

equity earnings yields is far less stable than

it at first appears. In America, for most of

the years since 1873, and even as recently as

the 1970s, shares traded at far higher

earnings yields—that is, lower p/e ratios—

relative to government bonds than they do

today (see the right-hand chart).

Earnings yield ratios have a problem.

Traditionally, investors have looked to cash

dividends as the ultimate source of share

value: these are pocketable returns, after all.

But as dividends have fallen out of fashion,

investors have had to rely on earnings,

flawed as they are, as a proxy. Shareholders

face two big risks; first, that without a

dividend stream they may never recoup

their investment, and second, that the flaws

in earnings make profits difficult to gauge.

Given these, it seems a stretch to put too

much faith in a fixed relationship with bond

yields, much less the view that shares are

fairly valued when these yields are equal.

• Better ratios. Some point to Tobin’s Q—

the ratio of a firm’s market value to the

replacement cost of its assets—as the best

way to understand market values. This

certainly has appeal, since it reflects the

costs a competitor would face in re-creating

a business. But replacement cost is hard to

measure, and is of little help in explaining

daily price movements. The next best thing,

comparing market prices with the book

value of assets, vastly underestimates the

value of companies with intangibles such as

patents and brands.

An alphabet soup of ratios is available to

escape the flaws of measuring earnings:

price-to-EBITDA (earnings before interest,

tax, depreciation and amortisation) and

price-to-cashflow, for example. These do a

somewhat better job, since they measure

profit in a way that, ideally, is more closely

tied to a company’s underlying

performance. But on these measures,

according to Peter Oppenheimer of HSBC,

stockmarkets in America, Britain and

France are still highly valued, though

German shares are less so.

Of course, no single metric can unlock

the secrets of share values. But the good

measures are those that are useful in bear

and bull markets alike. Discounted cash-

flow valuation, for instance, is another

metric that looks at the value of an entire

firm according to the profits it expects in

future. But it relies on a “risk premium”—

the additional return investors require to

compensate for the risks of holding

shares—which is both the most important,

and the most debated, figure in finance.

Differing views about the risk premium can

support almost any equity values. Recent

weeks have shown that this slippery idea is

central in the struggle between the bulls and

the bears. .

Figure 19.4: Article from the Economist on multiple valuation

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation Page 28

19.5. Intermediate summary

In Sections 19.1 – 19.4 we’ve examined 4 stock valuation methods:

•

Valuation method 1, the efficient markets approach, is based on the assumption that

market prices are correct.

•

Valuation method 2, the free cash flow (FCF) approach, values the firm by discounting

the future anticipated FCFs at the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). Sections

19.6 – 19.7 below show several methods of determining the WACC.

•

Valuation method 3, the equity payout approach, values all of the firm’s shares by

discounting the future anticipated payouts to equity. The discount rate is the firm’s cost

of equity r

E

.

•

Valuation method 4, the multiples approach, gives a comparative valuation of firms based

on ratios such as the price-earnings ratio.

In the next sections we discuss some issues related to valuation methods 2 and 3: We

discuss the computation of the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) and the cost of equity

r

E

(Sections 19.6 and 19.7).

19.6. Computing Target’s WACC, the SML approach

Valuation method 2 depends on the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), which was

previously discussed in Chapters 6 and 14. In this section we briefly repeat some of the things

said in Chapter 14 and show how to compute the firm’s WACC using the security market line

(SML).

The basic WACC formula is:

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation Page 29

()

1

EDC

ED

WACC r r T

ED DE

=+ −

++

To estimate the WACC we need to estimate the following parameters:

the cost of equity

the cost of the firm's debt

market value of the firm's equity

*

market value of the firm's debt

this is usually approximated by th

E

D

r

r

E

= number of shares current market value per share

D

=

=

=

=

e of the firm's debt

the firm's marginal tax rate

C

book value

T =

To illustrate the computation of the WACC, we use data for Target Corporation, a large

discount retailer. Figure 19.5 gives the relevant financial information for Target. Using the

Target data, we devote a short subsection to each of the WACC parameters, leaving the cost of

equity r

E

until last, since it is the most complicated.

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation Page 30

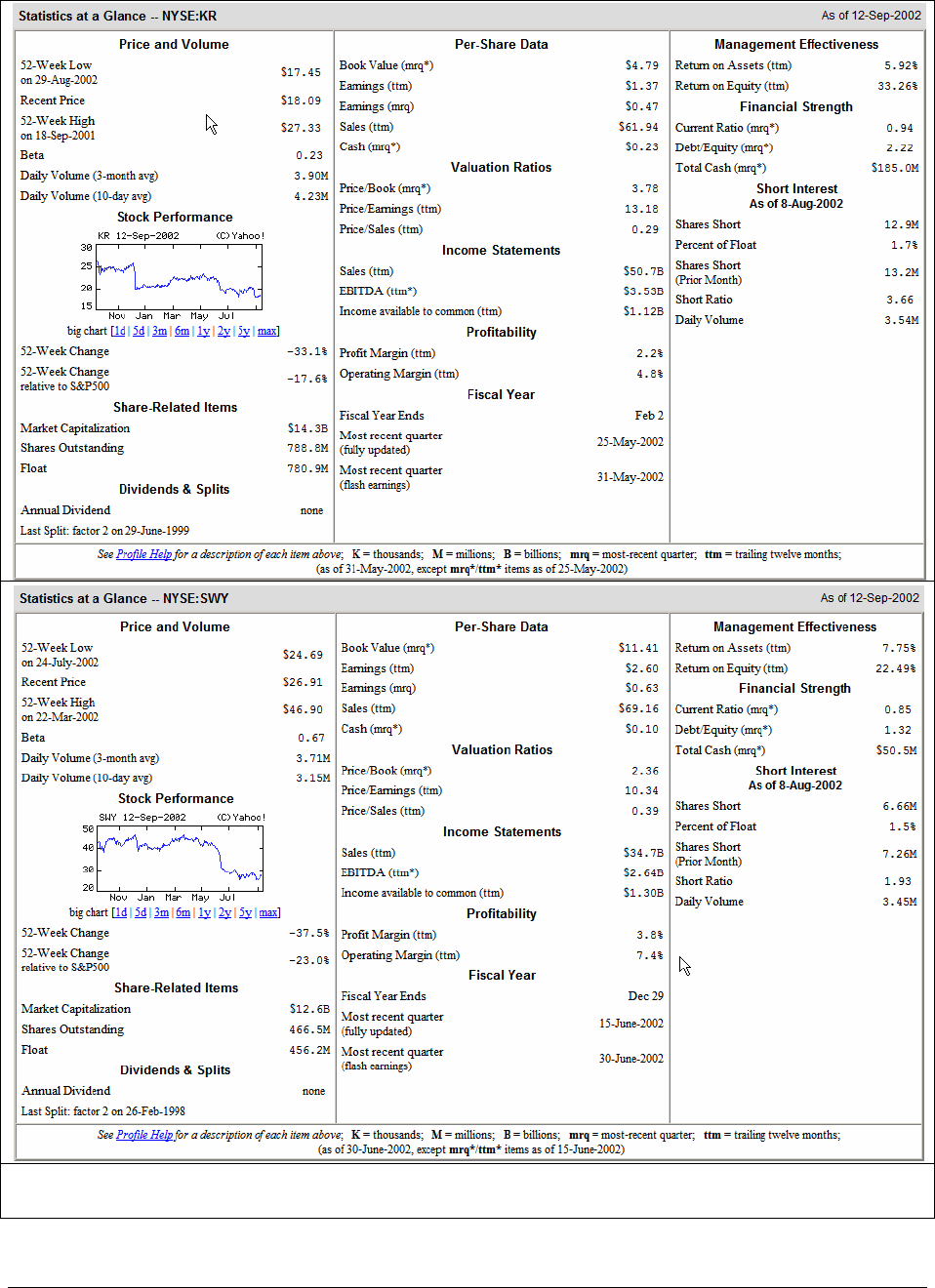

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

ABCDE

Income statement

2002 2001

Revenues 43,917 39,826

Cost of sales 29,260 27,143

Selling, general and administrative expenses 9,416 8,461

Credit card expense 765 463

Depreciation 1,212 1,079

Interest expense 588 473

Earnings before taxes 2,676 2,207

Income taxes 1,022 839

Net earnings 1,654 1,368

Balance sheet

Assets

2002 2001

Cash and cash equivalents 758 499

Accounts receivable 5,565 3,831

Inventory 4,760 4,449

Other current assets 852 869

Total current assets 11,935 9,648

Land, plant, property, and equipment

At cost 20,936 18,442

Accumulated depreciation 5,629 4,909

Net land, plant, property and equipment 15,307 13,533

Other assets 1,361 973

Total assets 28,603 24,154

Liabilities and shareholder equity

Accounts payable 4,684 4,160

Accrued liabilities 1,545 1,566

income taxes payable 319 423

Current portion of long-term debt and notes payable 975 905

Total current liabilities 7,523 7,054

Long-term debt 10,186 8,088

Deferred income taxes 1,451 1,152

Shareholders equity

Common stock 1,332 1,173

Accumulated retained earnings 8,111 6,687

Total equity 9,443 7,860

Total liabilities and shareholder equity 28,603 24,154

Other relevant information

Shares outstanding 908,164,702

Stock beta 1.16

Stock price, 1 February 2003 28.21

Year Dividends Repurchases

Total

equity

payout

1998 165 0 165

1999 178 0 178

2000 190 585 775

2001 203 20 223

2002 218 14 232

Growth rate 7.21% 8.89% <-- =(D57/D53)^(1/4)-1

Dividends and stock repurchases

TARGET CORPORATION

Figure 19.5. Financial information for Target Corp. We use this information to determine

Target’s cost of equity rE and its weighted average cost of capital (WACC).

PFE Chapter 19, Stock valuation Page 31

Computing the market value of Target’s equity, E

Target has 908,164,702 shares outstanding (cell B47, Figure 19.5). On 1 February 2003,

the day of the company’s annual report for its 2002 financial year, the stock price of Target was

$28.21 per share. Thus the market value of the company’s equity is 908,164,702*$28.21=

$25,619,326,243. Note that in the spreadsheets all numbers appear in millions, so that Target’s

equity value appears as E = $25,619.

Computing the market value of Target’s debt, D

The Target balance sheets differentiate between short term debt (“Current portion of

long-term debt and notes payable”—row 34 of Figure 19.5) and long-term debt (row 37). For

purposes of computing the debt for a WACC computation, both of these numbers should be

added together. This gives debt for Target as:

6

7

8

9

ABCD

2002 2001

Current portion of long-term debt and notes payable 975 905

Long-term debt in 2002 and 2001 (columns B and C)

10,186 8,088

Total debt, D

11,161 8,993 <-- =C8+C7

Estimating the cost of debt r

D

A simple method to compute the cost of debt r

D

is to calculate the average interest cost

over the year. In 2002 Target paid $588 interest (cell B9, Figure 19.5) on average debt of

$10,077. This gives r

D

= 5.84%:

13

14

15

ABCD

Interest paid, 2002

588

Average debt over 2002

10,077 <-- =AVERAGE(B9:C9)

Interest cost, r

D

5.84% <-- =B13/B14