Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.6 PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, AND GUIDELINES

4.4 EXAMPLES OF THE PRINCIPLES OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN

It is useful to illustrate the Principles of Universal Design with examples. Each of the designs pre-

sented here demonstrates a good application of one of the guidelines associated with the principles.

The design solutions included here are not necessarily universal in every respect, but each is a good

example of a specific guideline and helps to illustrate its intent.

Principle 1: Equitable Use

The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities.

• In other words, designs should appeal to diverse populations and offer everyone a comparable and

nonstigmatizing way to participate.

The water play area in a children’s museum shown in Fig. 4.1 simulates a meandering brook and

invites enjoyment for everyone in and around the water. It is appealing to and usable by people who

are short or tall, young children or older adults.

Principle 2: Flexibility in Use

The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities.

• In other words, designs should provide for multiple ways of doing things. Adaptability is one way

to make designs universally usable.

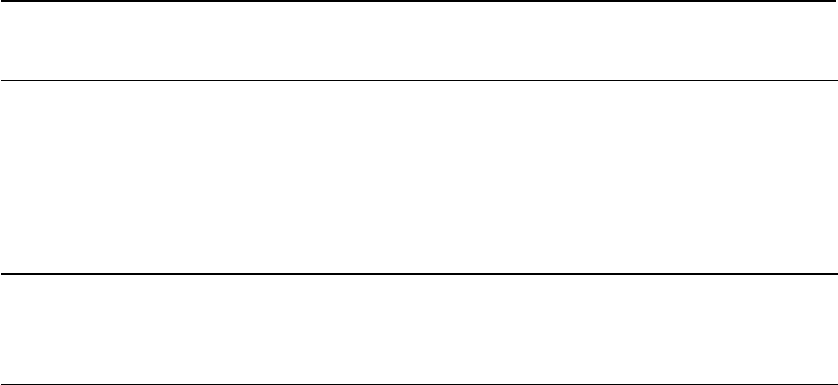

A medical examination table that adjusts in height can be lowered so that it is easier for the

patient to get onto and off of the table; it can also be raised so that it is easier for the health care

provider to examine and treat the patient at a level that is most effective and comfortable for him or

her and the specific procedure (Fig. 4.2).

Principle 3: Simple and Intuitive Use

Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language

skills, or current concentration level.

Principle 6: Low Physical Effort

6c. Minimize repetitive actions.

6d. Minimize sustained physical effort.

Principle 7: Size and Space for Approach and Use

Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or

mobility.

Guidelines:

7a. Provide a clear line of sight to important elements for any seated or standing user.

7b. Make reach to all components comfortable for any seated or standing user.

7c. Accommodate variations in hand and grip size.

7d. Provide adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal assistance.

Copyright © 1997 by North Carolina State University. Major funding provided by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research,

U.S. Department of Education.

TABLE 4.1 The Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0 (Connell et al., 1997) (Continued)

THE PRINCIPLES OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN 4.7

• In other words, make designs work in expected ways.

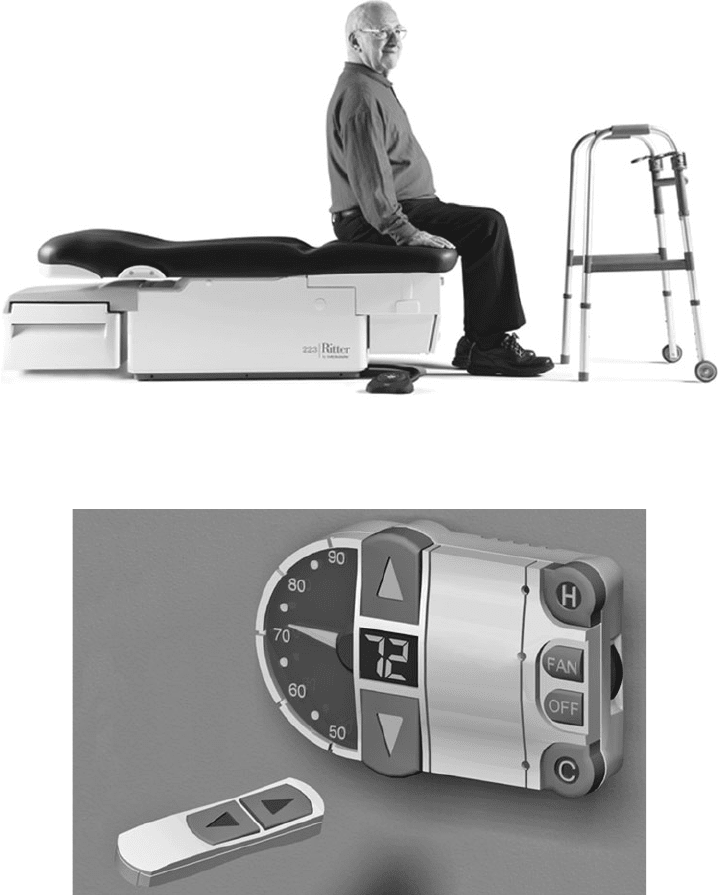

The prototype electronic thermostat designed at the Center for Universal Design provides

information in visual, audible, and tactile formats (Fig. 4.3). The functions are clearly laid out and

labeled; readouts are provided in both digital format (visible) and analog format (visible and tactile);

and the thermostat’s voice output (audible) helps users know what is happening when they push the

buttons. For example, when the user presses one of the directional keys, which has a raised tactile

arrow, the thermostat announces “72 degrees.” If the user keeps the down-pointing arrow depressed,

the thermostat will count down: “71, 70, 69, 68, . . .” When the user lets go, the thermostat repeats

“68 degrees.” The other control buttons would also trigger the thermostat to speak.

FIGURE 4.1 “Meandering brook” at children’s museum invites participation.

Long description: The photo shows a water play area in the sunshine outside

a children’s museum. It has multiple pools of varying heights that have curv-

ing side walls. The water in the pools cascades from one pool to the next. A

number of plastic balls float in the pools. Many people are playing in the water

and with the balls. Some people are standing, bending over, or sitting next to

the pools. Some of the children are standing or crouching in the pools.

4.8 PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, AND GUIDELINES

FIGURE 4.2 Height-adjustable exam table suits a wide range of patient and health care professional users.

Long description: The photo shows the side view of a height-adjustable medical examination table. The table is set to

its lowest height and is in a flat position. A man sits on the end of the table with his hands on the surface and feet flat

on the floor. A walker stands on the floor in front of him.

FIGURE 4.3 Prototype thermostat design by the Center for Universal Design.

Long description: The photo shows a computer rendering of a prototype thermostat and its remote

control. The left end of the thermostat is a semicircular, high-contrast analog gauge that displays the

temperature with a needle that points to a value between 45° when straight down to 95° when straight

up. To the right, in the middle of the thermostat body, is a large digital display that shows 72°. Above

the display is a large tactile button with an upward-pointing triangle, and below it is a button with a

downward-pointing triangle. In the upper corner of the right edge of the thermostat is a large, round,

tactile button labeled H for heat, and in the lower corner is a corresponding button labeled C for cool.

Between these two buttons are two other buttons, labeled FAN and OFF. The remote control has only

two large, tactile buttons, grouped closer to one end, with triangles that point up and down.

THE PRINCIPLES OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN 4.9

Principle 4: Perceptible Information

The design communicates necessary information to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the

user’s sensory abilities.

• In other words, designs should provide for multiple modes of output.

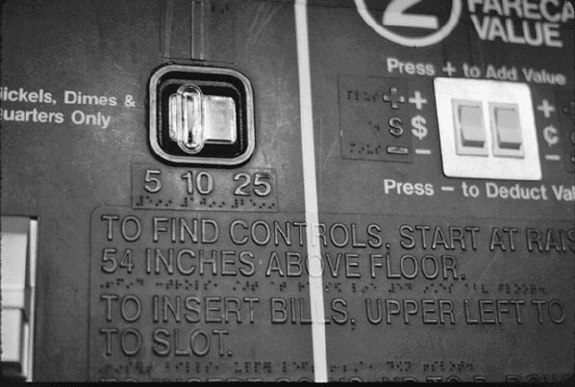

The subway fare machine shown in Fig. 4.4 provides tactile lettering in all-capital letters, which

is easier to feel with the fingertips, and high-contrast printed lettering in capital and lowercase let-

ters, which is easier to see with low vision. The fare machine also offers a push button for selecting

instructions to be presented audibly for users with vision impairments. Redundant audible feedback

is also helpful for people with disabilities that affect cognitive processing.

Principle 5: Tolerance for Error

The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions.

• In other words, designs should make it difficult for users to make a mistake; but if users do, the

error should not result in injury to the person or the product.

The dead-man switch, activated by a secondary bar that runs parallel to the handle of some power

lawn mowers (Fig. 4.5), requires the user to squeeze the bar and the handle together to make the

mower blade spin. If the two are not held together, the blade stops turning.

Principle 6: Low Physical Effort

The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue.

• In other words, designs should minimize strain and overexertion.

FIGURE 4.4 Subway fare machines with high-contrast and tactile lettering and audible output

on demand.

Long description: The photos show close-up views of a subway fare vending machine. The

machine surface is black, information on it is presented in white uppercase and lowercase lettering

and raised black uppercase lettering, and it has a button that is labeled “Push for audio.”

4.10 PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, AND GUIDELINES

FIGURE 4.5 The “dead-man” switch on a lawn mower handle requires conscious use.

Long description: The photo shows the handle portion of a lawnmower. The handle is made of

metal tubing, which is bent down on the sides and attaches to the mower body. A U-shaped bar

is connected to the tubing on the sides near the handle and is spring-loaded to rest in a position

away from the handle. The user must squeeze the bar against the handle for the mower blade

to operate.

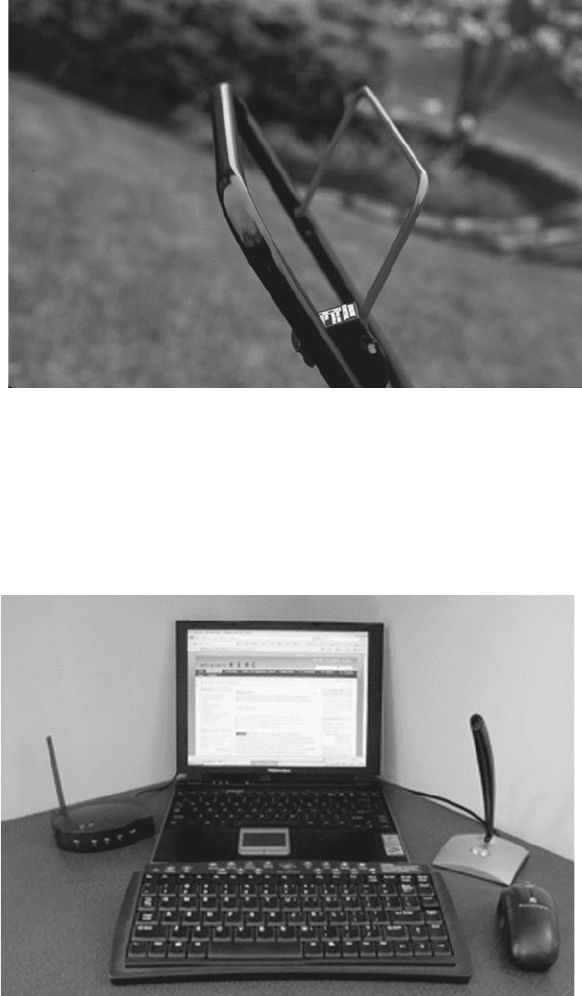

FIGURE 4.6 Computer hardware can be configured with a microphone to work with voice

recognition software.

Long description: The photo shows a laptop computer setup with multiple peripheral devices.

The computer is open, and a microphone sits to the right side.

THE PRINCIPLES OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN 4.11

A microphone and voice recognition software on a computer (Fig. 4.6) eliminate the need for

highly repetitive keystrokes or manual actions of any kind. This feature accommodates disabilities

of the hand and also reduces repetitive stress injuries to the hand.

Principle 7: Size and Space for Approach and Use

Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of the

user’s body size, posture, or mobility.

• In other words, designs should accommodate variety in people’s body sizes and ranges of motion.

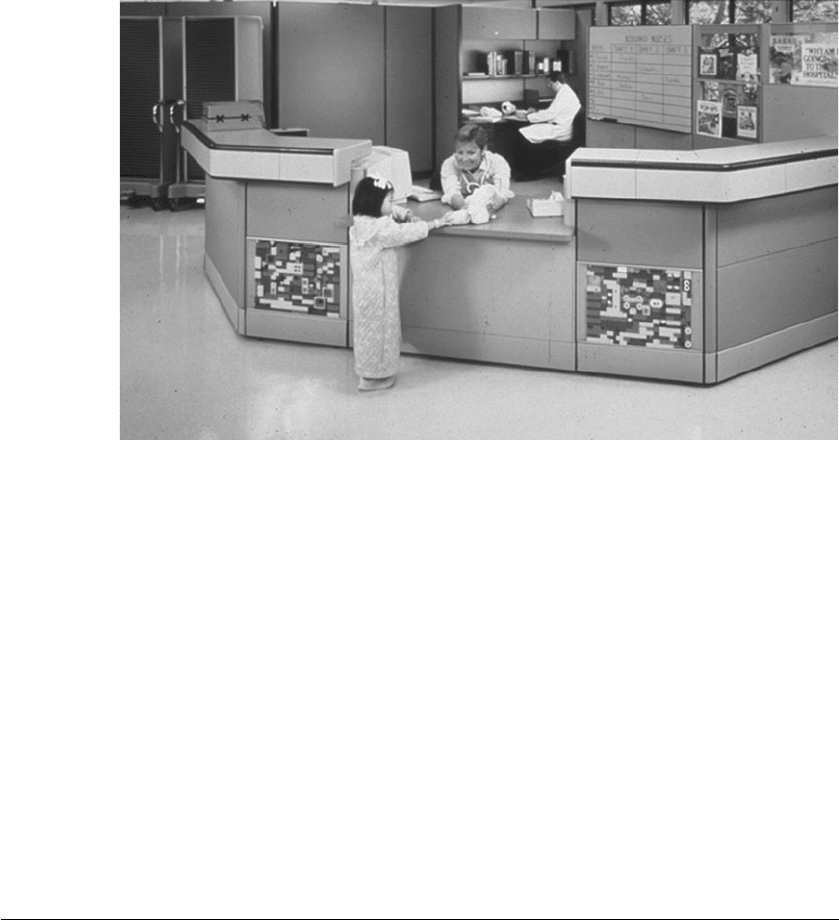

Reception desks that have counters at multiple heights (Fig. 4.7), for example, 28-in. high for sitting and

36-in. high for standing, accommodate people of varying heights, postures, and preferences.

4.5 CONCLUSION

The efforts described in this chapter to create a set of Principles of Universal Design were an attempt

to articulate a concept that embraces human diversity and applies to all design specialties. It is impor-

tant to recognize, however, that while the principles are useful, they offer only a starting point for the

universal design process. By its nature, any design challenge can be successfully addressed through

multiple solutions. Choosing the most appropriate design solution requires an understanding of and

negotiation among inevitable tradeoffs in accessibility and usability. This demands a commitment to

soliciting user input throughout the design process. It is essential to involve representative users in

FIGURE 4.7 Lowering one section of the nurses’ station counter in a hospital suits the needs of visitors who are

shorter or seated in a wheelchair or scooter.

Long description: The photo shows a nurses’ station in a hospital. Most of the counter is raised to standing elbow height,

but one section in the middle is cut away, which exposes the desk surface behind. A woman sits at the desk, interacting

with a small girl in front of the station who is wearing a hospital gown.

4.12 PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, AND GUIDELINES

evaluating designs during the development process to ensure that the needs of the full diversity of

potential users have been addressed.

The Principles of Universal Design helped to articulate and describe the different aspects of uni-

versal design. The principles’ purpose was to guide others, and in spite of their general nature, they

have proved useful in shaping projects of various types all over the world. It is the author’s hope that

they will continue to support and inspire ongoing advancement in the field of universal design.

4.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Center for Universal Design, Universal Design Exemplars (CD-ROM), Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina State

University, 2000a.

——, Universal Design Performance Measures for Products, Raleigh, N.C.: North Carolina State University,

2000b.

Connell, B. R., M. L. Jones, R. L. Mace, J. L. Mueller, A. Mullick, E. Ostroff, J. Sanford, et al., The Principles of

Universal Design, Version 2.0, Raleigh, N.C.: Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University, 1997.

Mueller, J. L., Case Studies on Universal Design, Raleigh, N.C.: Center for Universal Design, North Carolina

State University, 1997.

Story, M. F., J. L. Mueller, and R. L. Mace, The Universal Design File: Designing for People of All Ages and

Abilities, Raleigh, N.C.: Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University, 1998.

——, Images of Universal Design Excellence, Takoma Park, Md.: Universal Designers and Consultants, 1996.

CHAPTER 5

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION

ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS

WITH DISABILITIES

John Mathiason

5.1 INTRODUCTION

When the Universal Design Handbook was first published, the agreed international norms for the rights

of persons with disabilities were the United Nations Standard Rules for the Equalization of Opportunities

for Persons with Disabilities. In the intervening period, as a result of pressure from organizations of

persons with disabilities, the United Nations adopted a new human rights treaty, the United Nations

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. These include policies for universal design.

5.2 BACKGROUND

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was adopted by the General

Assembly on December 13, 2006 and entered into force on May 3, 2008. It was the culmination of a long

process of defining the rights of persons with disabilities. There was always a recognition that these

persons were included in the United Nations Declaration on Human Rights, but that more needed to be

done to ensure that these rights were exercised. As such, it joined a series of human rights conventions that

provided a binding programmatic and policy basis for state actions that would permit enjoyment of rights.

*

As of September 2009, the convention had 142 signatories and 66 ratifications. For states that have ratified

the convention, it is legally mandatory; for those that have signed, the country has specified an intention to

ratify. For the rest, the convention, and the Standard Rules that preceded it, is a normative guide.

The need for global standards was recognized for many years, first by persons with disabilities

themselves and then by policy makers in all countries. The United Nations Standard Rules for the

Equalization of Opportunity for Persons with Disabilities, adopted by the United Nations General

Assembly in 1993, were a response to this need.

The Standard Rules provided a politically agreed consensus on the basis of which the convention

could be elaborated. The applicability of the convention and the Standard Rules to universal design

can be understood in terms of the origins, limitations, content, and monitoring of the Standard Rules.

This chapter provides an overview of these elements.

5.1

*The others included the United Nations Conventions to Eliminate Racial Discrimination, on the Elimination of all Forms of

Discrimination against Women, Rights of the Child, Rights of Migrant Workers and Their Families.

5.2 PRINCIPLES, STANDARDS, AND GUIDELINES

5.3 THE PROCESS TOWARD A CONVENTION

The issue of disability had been on the United Nations’ social development agenda since the begin-

ning of the organization. Its original focus, like that of most countries, was on disabled veterans,

soldiers who had been wounded in World War II. Nonveteran, nonmale persons with disabilities

were largely invisible. It was assumed that the rights of persons with disabilities were protected by

the human rights standards expressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the

United Nations in 1948.

As the twentieth century progressed, more and more human rights advocates recognized that

detailed norms would have to be agreed upon if the rights of particular segments of the population

were to be adequately protected. Perhaps the first to recognize this were advocates for women’s

human rights, who sensed that the mere prohibition of discrimination on the basis of gender was not

sufficient to promote enjoyment of other human rights. Advocates for the rights of persons with dis-

abilities took note of these developments. They pressed successfully in the United Nations General

Assembly to have 1982 designated as International Year for Disabled Persons. The end result of the

year was the drafting of a World Plan of Action Concerning Disabled Persons and its adoption by

the General Assembly. The World Plan mentioned accessibility mostly in terms of stating that human

settlements, transportation, and information should be accessible, but not elaborating further.

By 1988, there was a concern among the members of the community concerned with disability

that the World Plan was not functioning as well as it should and that member states were not taking

it seriously. At a meeting of the Commission for Social Development, delegates from Sweden and

Italy worked together so that their delegations pushed for an international human rights convention

for persons with disability, but this was not strongly supported. As a compromise the Commission

for Social Development decided to begin the process of drafting an intermediate type of human

rights document, a declaration that would try to specify what states should do but would not have the

status of a treaty. The commission proposed that a process begin to draft what were called Standard

Rules for the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, using the World Plan as

its basis.

The process of negotiating the text included full participation of representatives of interna-

tional nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) concerned with disability such as Disabled Peoples’

International, the World Blind Union, and the World Federation of the Deaf, either as nongovern-

mental organizations or in national delegations. As a result, the draft text reflected much of the views

held by organizations representing persons with disabilities.

The content of the rules was negotiated rather quickly, partly because many of the rules were

vague and subject to interpretation but also because most of the negotiators were genuinely commit-

ted to the cause of disability.

Instead of being concerned with the content of the rules, the main debates in the committee were

focused on the monitoring mechanism. The persons with disability wanted a monitoring committee

to be funded from the regular budget of the organization. Governments, especially those that were

major contributors to the UN budget, were opposed to additional expense. The end result was a com-

promise creating the post of Special Rapporteur, an independent, outside expert who could report on

the extent to which the Standard Rules were implemented.

5.4 THE CONVENTION

The Standard Rules do not have the same status as a convention. In international treaty law, a conven-

tion is mandatory for all states that become party to it. Drafting and ratifying an international con-

vention is usually lengthy. In most countries, an international convention takes on the same status as

domestic law adopted by Parliament, and in most countries acceptance of an international convention

means that all national laws, regulations, and procedures have to be brought into conformity with the

convention. Governments are not legally obligated to implement the rules’ provisions. Rather, they

accept a moral obligation to implement as many of the provisions as they can.

UNITED NATIONS CONVENTION ON THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES 5.3

Organizations of persons with disabilities were increasingly concerned about the vagueness of the

Standard Rules. In 2000, the main global NGOs held a summit in Beijing, China, where they adopted

the Beijing Declaration that called on governments “to immediately initiate the process for an inter-

national convention.” The next world human rights conference, on racial discrimination at Durban in

2001, included in its declaration language urging governments to consider negotiating a convention.

In his address to the General Assembly shortly thereafter, the President of Mexico, Vicente Fox,

proposed the establishment of a special committee to draft a broad, comprehensive international con-

vention to promote and protect the rights and dignity of disabled persons.

*

As a result, the General

Assembly established an ad hoc committee to negotiate the convention. The resolution was spon-

sored by developing countries. No developed country (other than Mexico) was a sponsor.

The negotiations proceeded over five years in the ad hoc committee. Over the period, there were

regional meetings to discuss the convention. The sessions moved deliberately to deal with issues,

many of which were complex. Among the last issues to be agreed was a definition of disability, and

the solution was to avoid a definition. Other sections were more precise. An agreement was reached

on the text of the convention and it was adopted in December 2006 by consensus.

5.5 BASIC DEFINITIONS AND OBLIGATIONS

A fundamental question for policy is the definition of disability. It is the basis for determining what

“reasonable accommodations” must be made. It sets the conditions around which accessibility must

be designed and built. The rules reflected a consensus on definition that could be reached in the early

1990s and define disability as different functional limitations occurring in any population in any

country of the world through physical, intellectual, or sensory impairment; medical conditions; or

mental illness that may be permanent or transitory in nature. The rules also define the term handicap

as the loss or limitation of opportunities to take part in the life of the community on an equal level

with others. It describes the encounter between the person with a disability and the environment.

The convention largely dealt with these definitional issues by ignoring them in the section of the

convention entitled Definitions. Instead, Article 1, which sets out the purpose of the convention, states:

Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory

impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in

society on an equal basis with others.

The definition solves a number of problems by repeating the impairments listed in the Standard

Rules, specifying that they are long-term (rather than transitory) and conditioning them in terms of

barriers. The definition gives considerable scope for national legal definitions.

Universal design is given a significant place in the convention by being included in the basic

definitions found in Article 2:

“Universal design” means the design of products, environments, programmes and services to be usable by all

people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. “Universal design”

shall not exclude assistive devices for particular groups of persons with disabilities where this is needed.

Universal design should be read in the context of “reasonable accommodation,” another concept

discussed at length in the Standard Rules. Article 2 of the Convention states:

“Reasonable accommodation” means necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments not imposing a

disproportionate or undue burden, where needed in a particular case, to ensure to persons with disabilities the

enjoyment or exercise on an equal basis with others of all human rights and fundamental freedoms.

*http://fox.presidencia.gob.mx/en/activities/speeches/?contenido=258&pagina=3