Pounds N. The medieval city

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

[T]he most excellent proporcion therof: being devyded

in to xxxix quarters the most part square, with streats

very large and broad, all strayght as the same wear

layd with a line.

Report to the privy council on New Winchelsea

1

It was claimed in the last chapter that medieval towns each conformed

to one of two distinct plans, which in turn derived from the ways in

which the towns themselves had originated. One was the planned town,

the other the unplanned. This is, of course, a gross simplification of a

very complex reality. The best planned town became in the course of

time distorted in the absence of any effective regulatory authority. Con-

trariwise, there was more design in the unplanned town than is some-

times recognized. Nevertheless, this distinction has value and forms the

basis of this chapter.

THE PLANNED TOWN

The earliest human settlements were unplanned in the sense that the

layout of streets, houses, and public buildings was not controlled by a

local authority in accordance with an overall plan. Urban settlements

had grown by slow, unordered accretions from villages just as the latter

had grown from hamlets. But change was on its way. According to Aris-

totle (384–322 b.c.e.), Hippodamus of Miletus introduced “the art of

planning cities” and applied it to the construction of Piraeus, the port

CHAPTER 2

THE URBAN PLAN:

STREETS AND

STRUCTURES

THE MEDIEVAL CITY

22

city that served Athens.

2

This is usually taken to mean that Hippodamus

laid out straight streets, intersecting at right angles, and thus enclosing

rectangular blocks. This is, indeed, the street plan demonstrated in Pi-

raeus even today. Such a planned town implies the existence not only of

an overall authority, but also the need to create a relatively large center

of population. In 443 b.c.e. the Athenians founded the city of Thourioi

in southern Italy, divided by four streets lengthways and by three street

crossways, as well as other cities similarly planned in Italy and Asia

Minor. In fact the Hellenistic period of the fourth and third centuries

b.c.e. was characterized by an active program of founding cities—all of

them, so it appears, characterized by their planned layout.

The Greeks had not, in all probability, invented the regularly planned

city. It had appeared much earlier in the cities of the Middle East, in the

Tigris and Euphrates valleys. Nor did it end with the Greeks. The tradi-

tion was continued by the Etruscans in central and northern Italy. In-

deed, the Etruscans may have discovered the planned city before the

Greeks did. Rome itself was created by the synoecism or “coming to-

gether” of the villages that had previously crowned the seven hills, the

Septimontium, of ancient Rome, but the towns the Romans established

throughout their empire for the primary purpose of bringing civilization

to their subject peoples were mostly built according to a regular plan of

streets intersecting to enclose rectangular blocks. The best preserved of

these cities—and by far the most familiar—are Pompeii (It. Pompei) and

Herculaneum (It. Ercolano), preserved only because they were buried be-

neath the mud and ash spewed out by Vesuvius in 79 c.e. Throughout

the empire, from the Rhineland to North Africa, there were planned

towns. Many, perhaps the majority, fell to ruin and either were aban-

doned or survived only as villages after the collapse of the empire itself.

In Italy, however, a large number continued as functioning towns. But

even where they had been largely abandoned as inhabited places, their

street plan survived in some form and imposed itself on the settlements

that grew again on their sites during the Middle Ages.

In every such town, the plan became distorted. Buildings intruded into

the streets, forcing the streets to make small detours. Whole blocks were

cleared and became markets or were occupied by ecclesiastical founda-

tions. Nevertheless, the ghostly plan of a Roman city shows through even

today in the street plan of a Winchester, Trier, or Modena.

The planned European city was not restricted to those that derived

The Urban Plan: Streets and Structures

23

from the Greeks or the Romans. Similar conditions during the Middle

Ages contributed to similar developments. The medieval king or baron

might found a city on an empty tract of land. It might be nothing more

than an open-ended street, its houses aligned along each side with their

“burgage” plots reaching back behind them. It might consist of streets in-

tersecting at right angles. The one pattern would be straggling, the other

compact. It might be that agriculture was more important in the one than

in the other, or, more likely, that the need for security in a hostile envi-

ronment dictated a more compact plan around which a wall could be

built. Such towns could be found in all parts of medieval Europe.

THE UNPLANNED TOWN

No town was ever wholly unplanned in the sense of being a randomly

distributed assemblage of houses and public buildings. Every town once

had a nucleus that defined its purpose. This might have been a natural

feature such as a river crossing or a physical obstacle that necessitated a

break of bulk, the transfer of goods from one mode of transportation to

another—from ship to land, from animal transportation to a wheeled

cart. The nucleus might also have been a castle or natural place of se-

curity or defense, a church or an object of pilgrimage. The streets would

probably have originated in the paths by which people approached this

nuclear feature and would have formed a radiating pattern, interlinked

by cross streets and passageways. Some roads would have derived from

the ways by which people walked or drove their animals to the sur-

rounding fields.

Such was the Athens of the Pseudo-Dichaearchus, clustered at the foot

of the defensive hill we know today as the Acropolis. So also were count-

less towns in western and central Europe that grew up in response to the

needs of travelers and traders or to the need for security in an uncertain

age. In a few instances the origins of these towns are enshrined in leg-

end, as is the case in the beginnings of Rome. One cannot point to any

particular creative act. Unknown people at a time that can only be

guessed came together and formed a settlement. They built in whatever

way best suited their needs. If shipping and maritime trade were of pri-

mary interest, then their properties would in all likelihood be close to

the water’s edge. If security was foremost in their minds, then a naturally

defensible site would be chosen. If they saw profit in serving the needs

THE MEDIEVAL CITY

24

of a religious foundation such as a monastery and the pilgrims and oth-

ers who would be likely to visit it, then they would settle and build as

close as possible to its main entrance.

Soon after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, the new king of England,

William the Conqueror, founded a monastery on the site of the battle. A

small town took shape around it. A charter was granted and a market es-

tablished. Today there is a large, triangular open space, dominated by the

large and impressive gateway that leads to the former monastic precinct.

This was the town’s marketplace, though today no market is held there

and the business that was once transacted has been transferred to the

shops, which line the streets radiating from it. The town of Battle was

an unplanned growth. It responded to the needs of the monks and of the

traders who did business there. It is unique in that the pattern of its streets

and buildings is not precisely replicated elsewhere. The unplanned town

usually has an individuality that is the source of its interest and charm.

Superimposed on the pattern of streets, whatever their origin, were in-

stitutions of another kind: public buildings, both secular and religious,

and open spaces needed for economic or ceremonial purposes. In the case

of planned towns these needs had usually been anticipated when the

towns were founded. A block may have been left clear to serve as a mar-

ketplace or for the construction of a town- or gild-hall. Local pride re-

quired that it should be centrally placed, ornate, and conspicuous. It was

the focus of local authority, the seat of local government, and the ex-

pression of the independence guaranteed when the town was granted its

charter.

Nearby, and also occupying at least the larger part of a block, was the

central church. In a planned town the church is likely to have been es-

tablished at the time of the foundation of the town itself. In an un-

planned or organic town the church may have been even older, part of

the nucleus around which the town itself gradually took shape. In a large

town other churches—parochial, monastic, mendicant (that is, belong-

ing to the orders of friars), together with the private chapels of the elite

members of the community—intruded among the houses and shops

wherever there was the need for them and wealth with which to build

them. One must never underestimate the importance of the church in

the urban landscape of the Middle Ages. For this reason a whole chap-

ter is given in this book to the subject of the urban church.

The Urban Plan: Streets and Structures

25

THE WALLED TOWN

Security was a major factor in the creation and growth of most towns.

The Middle Ages were a lawless time, and most citizens had much to

lose not only from the activities of the common thief, but also from the

depredations of ill-disciplined armies who made it a practice to live off

the country. There was, therefore, some safety in numbers, and, added to

this, the medieval town usually took steps to defend itself against these

evils.

This necessity was not new. Classical Athens had protected itself

against its enemies and had built the “Long Walls,” a sort of fortified cor-

ridor linking it with its port, Piraeus. Throughout the Hellenistic world,

towns were walled, towers were built, and their gateways—always the

weakest point in their perimeter—were fortified. The art of fortification

spread to the Greeks of southern Italy, the Etruscans, and the Romans

themselves. Not all towns established within the jurisdiction of Rome

were protected by walls, however. The empire was, for much of its his-

tory, relatively peaceful. But from late in the third century conditions de-

teriorated, and there is good evidence in the reuse of masonry, torn from

temples and public buildings, that walls were hastily built in anticipation

of invasion. During the closing years of the western empire, towns were

in economic decline but were at the same time becoming increasingly

strongly fortified.

During the “dark” centuries that followed, urban housing and public

buildings decayed, but walls survived, though doubtless increasingly ru-

inous. When urban life began to revive, their walls were still there, an

object lesson in fortification and urban security. In town after town in

western Europe the walls that had given their citizens protection under

the empire were patched and repaired and, here and there extended to

take in a newly developed suburb, again made to serve. Take London, for

example. Short segments of London’s medieval walls still survive, but if

their foundations are examined carefully today they are found to be of

Roman workmanship.

3

The walls of imperial Rome, built under the Em-

peror Aurelian (215–275 c.e.), remained in use through the Middle Ages,

and fragments of them are still to be seen today.

Most towns that had survived from the late Roman period retained

not only their walls but also some semblance of their former street pat-

tern. When urban life revived, only a part of the former Roman enclo-

THE MEDIEVAL CITY

26

sure was occupied by houses and other buildings. There were open spaces

between the new town and the old walls. Gradually the settled area ex-

panded to fill out the area of the Roman town. Take, for example, the

city of Winchester, the Venta Belgarum of the Romans. It had for prac-

tical purposes been abandoned when the Roman legions left Britain in

410 c.e. It became an inhabited place again a century or two later. But

throughout the intervening years it had retained an aura of authority. It

became the capital, if such a term can be used at so early a date, of an

Anglo-Saxon kingdom. The Roman walls were again made to serve; their

gates and protective towers served as fixed points on which the newly

developing street pattern converged. It is not surprising, then, that the

medieval streets (and also their present-day successors) replicated with

only minor distortions the regular plan the Roman surveyors had laid out.

Throughout western and also much of southern Europe, towns of Roman

origin continue today to show a regular pattern of rectangular or subrec-

tangular blocks, little disturbed by the passage of time and the operations

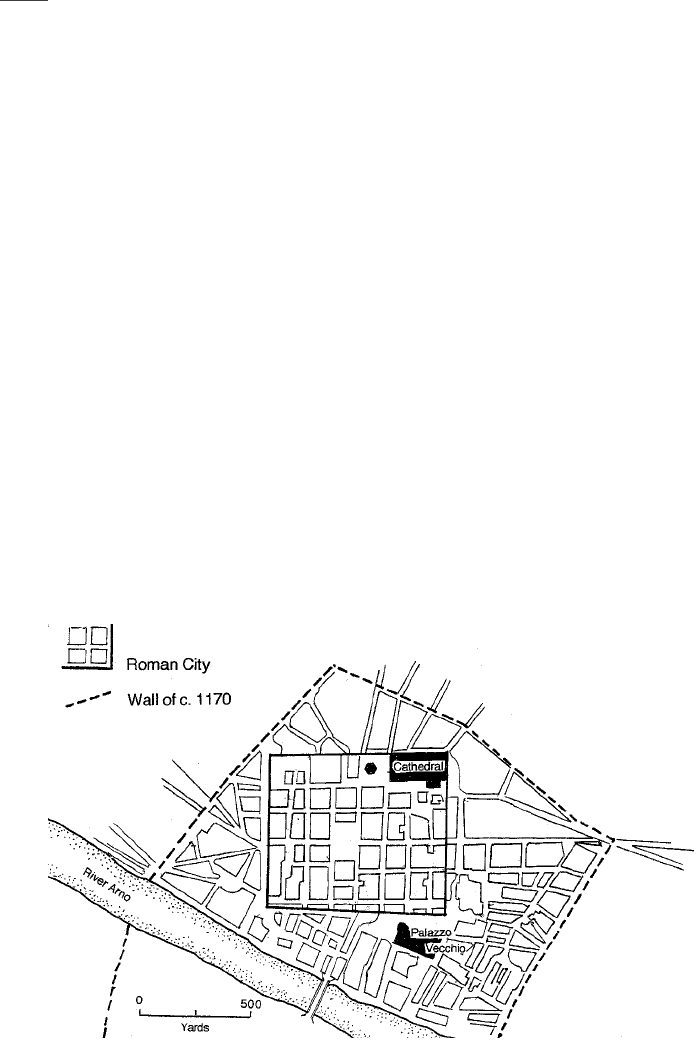

of unregulated builders (Figure 3).

The population of some towns increased greatly during the Middle

Ages, filling out the space within their walls and even spreading beyond

Figure 3. The expansion of Florence, showing extensions beyond the Roman

walls.

The Urban Plan: Streets and Structures

27

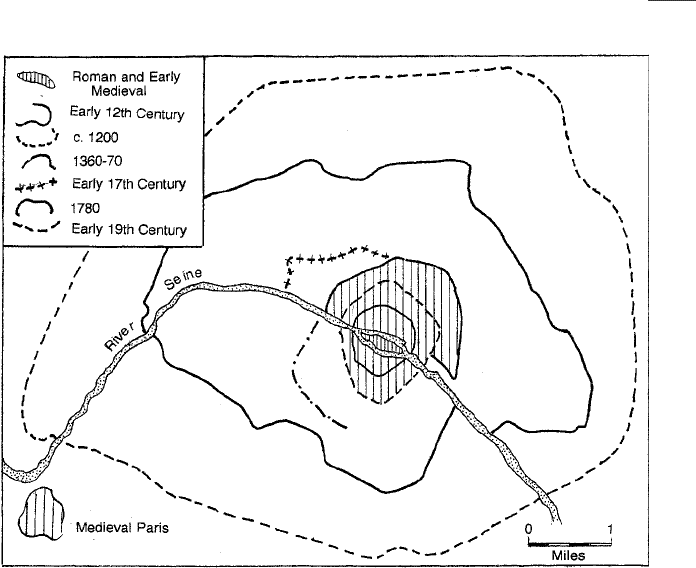

Figure 4. The expansion of Paris, showing the successive lines of the city walls.

them to form suburbs. In these cases it became necessary to build a fresh

line of walls enclosing or partially enclosing that which had been inher-

ited from the Romans. We thus have three kinds of walled towns. The

first consisted of those in which the growth of population had necessi-

tated the extension and rebuilding, wholly or in part, of their original

line of protective walls. Among them were Paris, the largest city in west-

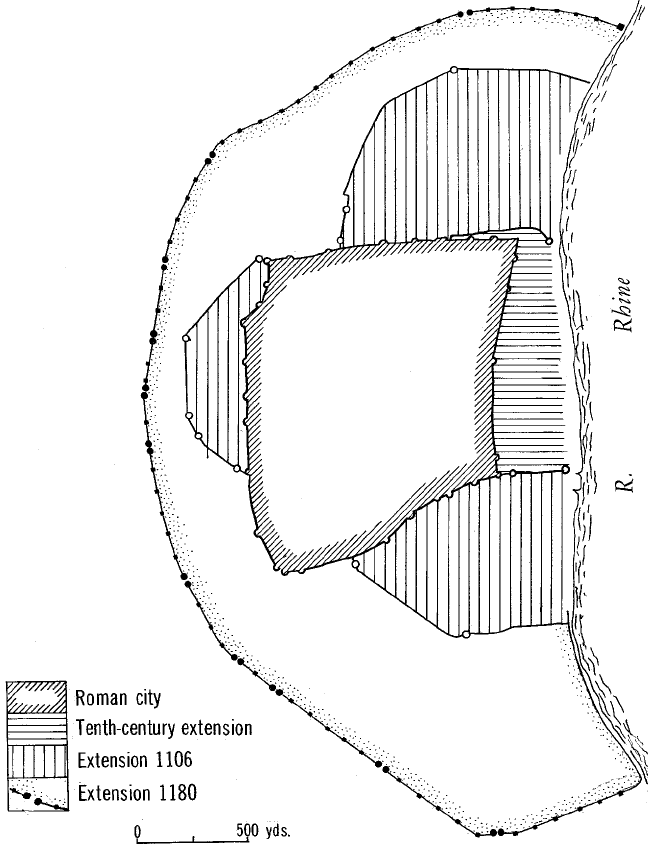

ern Europe (Figure 4), and Cologne (Köln) (Figure 5). In each of them,

successive lines of walls embraced an ever-expanding area.

Second, there are those towns in which the extension of urban space

was overgenerous. Their walls enclosed a greater area than could be pop-

ulated, and the towns did not grow as had been anticipated. Such was

Winchelsea, near the coast of southern England. The town and port of

Old Winchelsea had been overwhelmed by the sea and destroyed during

a storm in 1297. It was replanned on higher ground and on too lavish a

scale, and here we can see today the vacant or only partially occupied

blocks that resulted from the failure of reality to match the hopes and

Figure 5. Cologne (Köln), showing successive extensions of the enclosed area

beyond the subrectangular Roman room.

The Urban Plan: Streets and Structures

29

expectations of the city founders. Last, we have the great majority of

Roman towns whose fortunes revived until their buildings, streets, and

markets just about filled out the space that the Romans had occupied.

Here the Roman walls, or what was left of them, continued to do serv-

ice throughout the Middle Ages.

The effect of a wall was to set a limit—temporary in some cases—to

urban expansion. If there was any threat to urban security, and there was

throughout most of continental Europe, few citizens would venture to

live outside the line of the town’s protective walls if they could avoid it.

Even the smallest of towns had walls, and there was an assumption that

if a place was not surrounded by a ring of masonry, it could not then be

considered a town. During the sixteenth century it became a common

practice for engravers and mapmakers to produce panoramic views of

cities. Most were drawn with great care and attention to detail. The

biggest market for such drawings, it is said, was among the artillery mas-

ters who might be called upon to besiege the towns thus pictured and

who required to know how the walls were arranged and the locations of

important buildings. A series of these engravings was produced in the fif-

teenth century by Hartmann Schedel as illustrations to a history of the

known world.

4

Another and very much more accurate series was pro-

duced in the sixteenth century by Georg Braun and Franz Hogenberg.

5

Others came from the Dutch cartographers Hondius, Ortelius, and Mer-

cator. During the following century the brothers Merian did the same for

even very small towns in central Europe. These collections, totaling hun-

dreds of engravings, have two things in common: first, they all show in

great detail the encircling walls with their towers and well-defended gate-

houses, and second, they all show a broad, open space in front of the

walls. This gave a clear field of fire to the defenders without at the same

time offering any protection to the attackers.

Walls were functional. People were prepared to live in the utmost con-

gestion within the walls rather than face the dangers of life in the open

country beyond them. When unprotected suburbs began to take shape

outside the walls, we may be sure that the need for protection had ceased

to be uppermost in the minds of their citizens. And yet, even though

siege craft was a well-developed branch of the art of war, there is little

evidence that most walled towns were ever subjected to attack. It was

the castle, the fortified home of an individual, that was most likely to be

THE MEDIEVAL CITY

30

besieged. The siege of a town might be prolonged, difficult, and costly,

and in feudal warfare, which was almost by definition carried on by the

barons and their retainers, the castle was more important than the town,

whose citizens did not readily involve themselves in feudal disputes. Fur-

thermore, to lay siege to a town with perhaps as much as a mile of de-

fended walls called for very large forces, which few medieval kings or

barons could command. An urban siege was likely to be a long, drawn-

out affair, and feudal armies were, by the conventions of the age, in the

field for only a short period in each year. This is illustrated by one of the

very few well-documented urban sieges of medieval Europe: that of

Byzantium by the Ottoman Turks. The Turks had occupied the hinter-

land of Byzantium (Istanbul) for almost a century before they dared to

make a direct assault on the city, and even then the siege lasted for many

months.

If urban sieges were so few, why then did the towns’ citizens go to the

immense cost and inconvenience of constructing walls? The answer must

be in order to provide effective defenses against their potential attack-

ers. Walls were a very significant form of insurance. They served another

purpose also—giving protection from lesser evils, from the small bands

that occasionally terrorized the countryside. Then, too, there was the

small matter of local pride. The town walls were pictured in a town’s her-

aldry, and were replicated each time the town seal was used to authenti-

cate a document. Last, walls were a matter of convenience. They set a

limit to urban sprawl, and the walkway behind the ramparts served as a

means of getting across the town without having to negotiate its busy

streets. The citizens of Coventry once complained that the wall-walk was

so decayed that people were obliged to resort to the unpaved streets deep

in mud.

THE MULTI-FOCAL TOWN

According to legend, which may not have been so very far from the

truth, the city of Rome grew from the merger of a small number of vil-

lages that had previously crowned its hills. The space between them was

gradually drained, the Cloaca Maxima (the Great Drain) taking the water

that lay on the lower ground, where the Forum was later to be estab-

lished, down to the river Tiber. An enclosing wall, the Servian Wall of

some six miles, then converted the seven hills into a single city. The Au-