Potter T.D., Colman B.R. (co-chief editors). The handbook of weather, climate, and water: dynamics, climate physical meteorology, weather systems, and measurements

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6 LIGHTNING DETE CTION

During the 1980s, a major breakthrough in lightning detection occurred with the

development of lightning detect ion networks. Two distinct approaches were deve-

loped to detect and locate CGs. One was based on magnetic direction finding (MDF)

and the second on time-of-arrival (TOA) approaches. Krider et al. (1980) described

one of the first applications of an MDF-based system, the location of CG flashes in

remote parts of Al aska, which might start forest fires. The TOA technique was

applied to research and operations in the United States in the late 1980s (Lyons

et al., 1985, 1989). As various MDF and TOA networks proliferated, it soon was

evident that a merger of the two techniques was both technologically and economic-

ally desirable. The current U.S. National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN)

(Cummins et al., 1998) consists of a hybrid system using the best of both

approaches.

The NLDN uses more than 100 sensors communicating via satellite links to a

central control facility in Tucson, Arizona, to provide real-time information on CG

events over the United States. While employing several different configurations, it

has been operating continuously on a nationwide basis since 1989. Currently, the

mean flash location accuracy is approaching 500 m and the flash detection efficiency

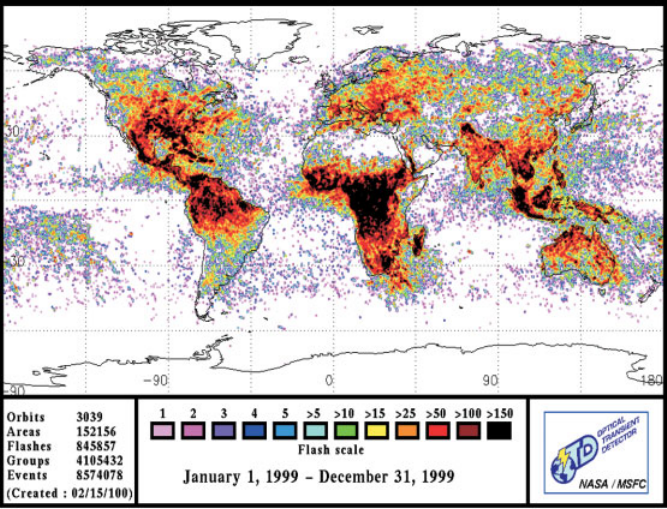

Figure 2 (see color insert) Map of global lightning detected over a multiyear period by

NASA’s Optical Transient Detector flying in polar orbit. See ftp site for color image.

416

ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY AND LIGHTNING

ranges between 80 and 90%, varying slightly by region (Cummins et al., 1998). It

can provide coverage for several hundred kilometers beyond the U.S. coast line,

although the detection efficiency drops off with range. The networks are designed

to detect individual CG strokes, which can then be combined to flashes. The NLDN

provides data on the time (nearest millisecond), location (latitude and longitude),

polarity, and peak current of each stroke in a flash, along with estimates of the

locational accuracy. National and regional networks using similar technology are

gradually evolving in many areas, including Japan, Europe, Asia, Australia, and

Brazil. The Canadian and U.S. networks have effectively been merged into a

North American network (NALDN).

In the United States, lightning data are available by commercial subscription in a

variety of formats. Users can obtain real-time flash data via satellite. Summaries of

ongoing lightning-producing storms are distributed through a variety of websites.

Pagers are being employed to alert lightning-sensitive facilities, such as golf courses,

to the approach of CGs. Historical flash and stroke data can also be retrieved from

archives (see www.LightningSt orm.com). These are used for a wide variety of

scientific research programs, electrical system design studies, fault finding, and

insurance claim adjustin g.

Future detection developments may include three-dimensional lightning mapping

arrays (LMAs). These systems, consisting of a network of very high frequency

(VHF) radio receivers, can locate the myriad of electrical emissions produced by

a discharge as it wends its way through the atmosphere. Combined with the existing

CG mapping of the NLDN, total lightning will be recorded and displayed in

real time. Such detection systems are now being tested by several private firms,

universities, and government agencies.

A new long-range lightning detection technique employs emissi ons produced by

CG lightning events in the extremely low frequency (ELF) range of the spectrum. In

the so-called Schumann resonance bands (8, 14, 20, 26, ...Hz) occasional very large

transients occur that stand out against the background ‘‘hum’’ of all the world’s

lightning events. These transients are apparently the result of atypical lightning

flashes that transfer massive amounts of charge (>100 C) to ground. It is suspected

many of these flashes also produce mesospheri c sprites (see below) (Huang et al.,

1999). Since the ELF signatures travel very long distances within Earth–ionosphere

waveguide, just a few ELF receivers are potentially capable of detecting and locating

the unusual events on a global basis.

7 LIGHTNING PROTECTION

Continued improvement in the detection of lightning using surface and space-based

systems is a long-term goal of the atmospheric sciences. This must also be accom-

panied by improving alerts of people and facilities in harm’s way, more effective

medical treatment for those struck by lightning, and improved engineering practice

in the hardening of physical facilities to withstand a lightning strike.

7 LIGHTNING PROTECTION 417

The U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) does not issue warnings specifically

for lightning, although recent policy is to incl ude it within special weather statements

and warnings for other hazards (tornado, hail, high wind s). Thus members of the

public are often left to their own discretion as to what safety measures to take. When

should personnel begin to take avoidance procedures? The ‘‘flash-to-bang method’’

as it is sometimes called is based on the fact that while the optical signature of

lightning travels at the speed of light, thunder travels at 1.6 km every 5 s. By count-

ing the time interval between seeing the flash and hearing the thunder, one can

estimate the distance rather accurately. The question is then how far away might

the next CG flash jump from its predecessor’s location? Within small Florida air

mass thunderstorms, the average value of the distance between successive CG strikes

is 3.5 km (Uman and Krider, 1989). However, recently statistics from larger midwestern

storms show the mean distance between successive flashes can often be 10 km or

more (30 s flash-to-bang or more). According to Holle et al. (1992), lightning from

receding storms can be as deadly as that from approaching ones. People are struck

more often near the end of storms than during the height of the storm (when the

highest flash densities and maximum property impacts occur). It appears that people

take shelter when a storm approaches and remain inside while rainfall is most

intense. They fail to appreciate, however, that the lightning threat can continue

after the rain has diminished or even ceased, for up to a half hour. Also, the later

stages of many storms are characterized by especially powerful and deadly þCG

flashes. Thus, has emerged the 30:30 rule (Holle et al., 1999). If the flash-to-bang

duration is less than 30 s, shelter should be sought. Based upon recent research in

lightning casualties, persons should ideally remain sheltered for about 30 min after

the cessation of audible thunder at the end of the storm.

Where are people struck by lightning? According to one survey, 45% were in

open fields, 23% were under or near tall or isolated trees, 14% were in or near water,

7% were on golf courses, and 5% were using open-cab vehicles. Another survey

noted that up to 4% of injuries occurred with persons talking on (noncordless)

telephones or using radio transmitters. In Colorado some 40% of lightning deaths

occur while people are hiking or mountain climbing during storms. The greatest

risks occur to those who are among the highest points in an open field or in a boat,

standing near tall or isolated trees or similar objects, or in contact with conducting

objects such as plumbing or wires connected to outside conductors. The safest

location is inside a substantial enclosed building. The cab of a metal vehicle with

the windows closed is also relatively safe. If struck, enclosed structures tend to

shield the occupants in the manner of a Faraday cage. Only rarely are people

killed directly by lightning while inside buildings. These include persons in contact

with conductors such as a plumber leaning on a pipe, a broadcaster talking into a

microphone, persons on the telephone, or an electrician working on a power panel.

A lightning strike is not necessarily fatal. According to Cooper (1995) about 3 to

10% of those persons struck by lightning are fatally injured. Of those struck, fully

25% of the survivors suffered serious long-term after effects including memory loss,

sleep disturbance, attention deficits, dizziness, numbness=paralysis, and depression.

The medical profession has been rather slow to recognize the frequency of lightning-

418 ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY AND LIGHTNING

related injuries and to develop treatment strategies. There has, fortunately, been an

increasing interest paid to this topic over the past two decades (Cooper, 1983, 1995;

Andrews et al., 1988, 1992). Persons struck by lightning who appear ‘‘dead’’ can

often be revived by the prompt application of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

The lack of external physical injury does not preclude the possibility of severe

internal injuries.

Lightning can and does strike the same place more than once. It is common for

the same tall object to be struck many times in a year, with New York City’s Empire

State Building being struck 23 times per year on average (Uman, 1987). From a risk

management point of view, it should be assumed that lightning cannot be ‘‘stopped’’

or prevented. Its effects, however, can be greatly minimized by diversion of the

current (providing a controlled path for the current to follow to ground) and by

shielding.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy (1996), first-level protection of

structures is provided by the lightning grounding system. The lightning leader is

not influenced by the object that is about to be struck until it is only tens of meters

away. The lightning rod (or air terminal) developed by Benjamin Franklin remains a

key component for the protection of structures. Its key function is to initiate an

upward-connecting streamer discharge when the stepped leader approaches within

striking distance. Air terminals do not attract significantly more strikes to the struc-

ture than the structure would receive in their absence . They do create, however, a

localized preferred strike point that then channels the current to lightning conductors

and safely down into the ground. To be effective, a lightning protection system must

be properly designed, installed, and maintained. The grounding must be adequate.

Sharp bends (less than a 20-cm radius) can defeat the conductor’s function. The

bonding of the components should be thermal, not mechanical , whenever possi ble.

Recent findings sugges t that air terminals with rounded points may be more effective

than those with sharp points.

Sensitive electronic and electrical equipment should be shielded. Switching to

auxiliary generators, surge protectors, and uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs)

can help minimize damag e from direc t lightning strikes or power surges propagating

down utility lines from distant strikes. In some cases, the most practical action is to

simply disconnect valuable assets from line power until the storm has passed.

There is still much to be learned about atmospheric electrical phenome na and

their impacts. The characteristics of lightning wave forms and the depth such

discharges can penetrate into the ground to affect buried cables are still under

investigation. Ongoing tests using rocket-triggered lightning are being conducted

by the University of Florida at its Camp Blanding facility in order to test the hard-

ening of electrical systems for the Electric Power Research Institute.

The notion that lightning is an ‘‘act of God’’ against which there is little if any

defense is beginning to fade. Not only can we forecast conditions conducive to

lightning strikes and moni tor their progress, but we are beginning to understand

how to prevent loss of life, treat the injuries of those harmed by a strike, and decrease

the vulnerability of physical assets to lightning.

7 LIGHTNING PROTECTION 419

8 IMPACTS OF LIGHTNING UPON THE MIDDLE ATMOSPHERE

Science often advances at a deliberate and cautious pace. Over 100 years passed

before persistent reports of luminous events in the stratosphere and mesosphere,

associated with tropo spheric lightning, were accepted by the scientific community.

Since 1886, dozens of eyewitness accounts, mostly published in obscure meteoro-

logical publications, have been accompanied by articles describing meteorol ogical

esoterica such as half-meter wide snow flakes and toads falling during rain showers.

The phenomena were variously described using terms such ‘‘cloud-to-space light-

ning’’ and ‘‘rocket lightning.’’ A typical description might read, ‘‘In its most typical

form it consists of flames appearing to shoot up from the top of the cloud or, if the

cloud is out of sight, the flames seem to rise from the horizon.’’ Such eyewitness

reports were largely ignored by the nascent atmospheric electricity community—

even when they were posted by a Nobel Prize winning physicist such as

C.T.R. Wilson (1956). During the last three decades, several compendia of similar

subjective reports from credible witnesses worldwide were prepared by Otha H.

Vaughan (NASA Marshall) and the late Bernard Vonnegut (The State University

of New York—Albany). The events were widely dispersed geographically from

equatorial regions to above 50

latitude. About 75% of the observations were

made over land. The eyewitness descriptions shared one common characteristic—

they were perceived as highly atypical of ‘‘normal’’ lightning (Lyons and Williams,

1993). The reaction of the atmospheric science community could be summarized as

casual interest at best. Then, as so often happens in science, serendipity intervened.

The air of mystery began to dissipate in July 1989. Scientists from the University

of Minnesota, led by Prof. John R. Winckler, were testing a low-light camera system

(LLTV) for an upcoming rocket flight at an observatory in central Minnesota (Franz

et al., 1990). The resulting tape contained, quite by accident, two fields of video that

provided the first hard evidence for what are now called sprites. The twin pillars of

light were assumed to originate with a thunderstorm system some 250 km to the

north along the Canadian border. The storm system, while not especially intense, did

contain a larger than average number of positive polarity cloud-to-ground (þCG)

lightning flashes. From this single observation emanated a decade of fruitful research

into the electrodynamics of the middle atmosphere.

Spurred by this initial discovery, in the early 1990s NASA scientists searched

videotapes from the Space Shuttle’s LLTV camera archives and confirmed at least 17

apparent events above storm clouds occurring worldwide (Boeck et al., 1998). By

1993, NASA’s Shuttle Safety Office had developed concerns that this newly discov-

ered ‘‘cloud-to-space lightning’’ might be fairly common and thus pose a potential

threat to Space Shuttle missions especially during launch or recovery. Based upon

the available evidence, the author’s hunt for these elusive events was directed a bove

the stratiform regions of large mesoscale convective systems (MCSs), known to

generate relatively few but often very energetic lightning discharges. On the night

of July 7, 1993, an LLTV was deployed for the first time at the Yucca Ridge Field

Station (YRFS), on high terrain about 20 km east of Fort Collins, Colorado. Exploit-

ing an uninterr upted view of the skies above the High Plains to the east, the LLTV

420 ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY AND LIGHTNING

was trained above a large nocturnal MCS in Kansas, some 400 km distant (Lyons,

1994). Once again, good fortune intervened as 248 sprites were imaged over the next

4 h. Analyses revealed that almost all the sprites were associated with þCG flashes,

and assumed an amazing variety of shapes (Fig. 3). Within 24 h, in a totally inde-

pendent resear ch effort, sprites were imaged by a University of Alaska team onboard

the NASA DC8 aircraft over Iowa (Sentman and Wescott, 1993). The following

summer, the University of Alaska’s flights provided the first color videos detailing

the red sprite body with bluish, downward extending tendrils. The same series of

flights documented the unexpected and very strange blue jets (Wescott et al., 1995).

By 1994 it had become apparent that there was a rapidly developing problem with

the nomenclature being used to describe the various findings in the scientific litera-

ture. The name sprite was selected to avoid employing a term that might presume

more about the physics of the phenom ena than our knowledge warranted. Sprite

replaced terms such as ‘‘cloud-to-space’’ lightning and ‘‘cloud-to-ionosphere

discharge’’ and similar appellations that were initially used. Today a host of pheno-

mena have been named: sprites, blue jets, blue starters, elves, sprite halos, and trolls,

with perhaps others remaining to be discovered. Collectively they have been termed

transient luminous events (TLEs).

Since the first sprite observations in 1989, the scientific community’s mispercep-

tion of the middle atmosphere above thunderstor ms as ‘‘uninteresting’’ has comple-

tely changed. Much has been learned about the morphology of TLEs in recent years.

Sprites can extend vertically from less than 30 km to about 95 km. While telescopic

investigations reveal that individual tendril elements may be of the order of 10 m

across, the envelope of the illuminated volume can exceed 10

4

km

3

. Sprites are

Figure 3 One of the many shapes assumed by sprites in the mesosphere. Top may be near

95 km altitude with tendril-like streamers extending downward toward 40 km or lower.

Horizon is illuminated by the flash of the parent lightning discharge. Image obtained using

a low-light camera system at the Yucca Ridge Field Station near Ft. Collins, CO. Sprite is

some 400 km away.

8 IMPACTS OF LIGHTNING UPON THE MIDDLE ATMOSPHERE 421

almost always preceded by þCG flashes, with time lags of less than 1 to over 100 ms.

To date, there are only two documented cases of sprites associated with negative

polarity CGs. The sprite parent þCG peak currents range widely, from under 10 kA

to over 200 kA, though on average the sprite þCG peak current is 50% higher than

other þCGs in the same storm. High-speed video images (1000 fps) suggest that

many sprites usually initiate around 70 to 75 km from a small point, and first extend

downward and then upward, with development at speeds around 10

7

m=s. Sprite

luminosity on typical LLTV videos can endure for tens of milliseconds. Photometry

suggests, however, that the brightest elements usually persist for a few milliseconds,

though occasionally small, bright ‘‘hot spots’’ linger for tens of milliseconds. By

1995, sprite spectral measurements by Hampton et al. (1996) and Mende et al.

(1995) confirmed the presence of the N

2

first positive emission lines. In 1996,

photometry provided clear evidence of ionization in some sprites associated with

blue emissions within the tendrils and sometimes the sprite body (Armstrong et al.,

2000). Peak brightness within sprites is on the order of 1000 to 35,000 kR. In 7 years

of observations at Yucca Ridge, sprites were typically associated with larger storms

(>10

4

km

2

radar echo), especially those exhibiting substantial regions of stratiform

precipitation (Lyons, 1996). The TLE-generating phase of High Plains storms

averages about 3 h. The probability of optical detection of TLEs from the ground

in Colorado is highest between 0400 and 0700 UTC. It is suspected that sprite

activity maximizes around local midnight for many storms around the world. The

TLE counts observed from single storm systems has ranged from 1 to 776, with 48

as an average count. Sustained rates as high as once every 12 s have been noted, but

more typical intervals are on the order of 2 to 5 min.

Can sprites be detected with the naked eye? The an swer is a qualified yes. Most

sprites do not surpass the threshold of detection of the dark-adapted human eye, but

some indeed do. Naked-eye observations require a dark (usually rural) location, no

moon, very clean air (such as visibilities typical of the western United States) and a

dark-adapted eye (5 min or more). A storm located 100 to 300 km distant is ideal if it

contains a large stratiform precipitation area with þCGs. The observer should stare

at the region located some 3 to 5 times the height of the storm cloud. It is best to

shield the eye from the lightning flashing within the parent storm. Often sprites are

best seen out of the corner of the eye. The event is so transient that often observers

cannot be sure of what they may have seen. The perceived color may not always

appear ‘‘salmon red’’ to any given individual. Given the human eye’s limitations in

discerning color at very low light levels, some report seeing sprites in their natural

color, but others see them as white or even green.

While most TLE discoveries came as a surprise, one was predicted in advance

from theoretical arguments. In the early 1990s, Stanfo rd University researchers

proposed that the electromagnetic pulse (EMP) from CG flashes could induce a

transient glow at the lower ledge of the ionosphere between 80 and 100 km altitud es

(Inan et al., 1997). Evidence for this was first noted in 1994 using LLTVs at Yucca

Ridge. Elves were confirmed the following year by photometric arrays deployed at

Yucca Ridge by Tohoku University (Fukunishi et al., 1996). Elves, as they are now

called, are believed to be expanding quasi-torroidal structures that attain an inte-

422 ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY AND LIGHTNING

grated width of several hundred kilometers. (The singular is elve, rather than elf, in

order to avoid confusion with ELF radio waves, which are used intensively in TLE

studies.) Photometric measurements sugges t the elve’s intrinsic color is red due to

strong N

2

first positive emissions. While relatively bright (1000 kR), their duration is

<500 ms. These are usually followed by 300 ms very high peak current (often

>100 kA) CGs, most of which are positive in polarity. Stanford University research-

ers, using sensitive photometric arrays, documented the outward and downward

expansion of the elve’s disk. They also suggest many more dim elves occur than

are detected with conventional LLTVs. It has been suggested that these fainter elves

are more evenly distributed between positive and negative polarity CGs.

Recently it has been determined that some sprites are preceded by a diffuse disk-

shaped glow that lasts several milliseconds and superficially resembles elves. These

structures, now called ‘‘halos,’’ are less than 100 km wide, and propagate downward

from about 85 to 70 km altitude. Sprite elements sometimes emerge from the lower

portion of the spri te halo’s concave disk.

Blue jets are rarely observed from ground-based observatories, in part due to

atmospheric scattering of the shorter wavelengths. LLTV video from aircraft

missions revealed blue jets emerging from the tops of electrically active thunder-

storms. The jets propagate upwards at speeds of 100 km=s reaching terminal

altitudes around 40 km. Their estimated brightness is on the order of 1000 kR.

Blue jets do not appear to be associated with specific CG flashes. Some blue jets

appear not to extend very far above the clouds, only propagating as bright channels

for a few kilometers above the storm tops. These nascent blue jets have been termed

blue starters. During the 2000 observational campaign at Yucca Ridge, the first blue

starters ever imaged from the ground were noted. They were accompanied by very

bright, short-lived (20 ms) ‘‘dots’’ of light at the top of MCS anvil clouds. A

NASA ER2 pilot flying over the Dominican Republic high above Hurricane Georges

in 1998 described seeing luminous structures that resembled blue jets.

The troll is the most recent addition to the TLE family. In LLTV videos, trolls

superficially resemble blue jets, yet they clearly contain significant red emissions.

Moreover, they occur after an especially bright sprite in which tendrils have extended

downward to near cloud tops. The trolls exhibit a luminous head leading a faint trail

moving upwards initially around 150 km=s, then gradually decelerating and disap-

pearing by 50 km. It is still not known whether the preceding sprite tendrils actually

extend to the physical cloud tops or if the trolls emerge from the storm cloud per se.

Worldwide, a variety of storm types have been associated with TLEs. These

include the larger midlatitude MCSs, tornadic squall lines, tropical deep convection,

tropical cyclones, and winter snow squalls over the Sea of Japan. It appears that the

central United States may be home to some of the most prolific TLE producers, even

though only a minority of High Plains thunde rstorms produce TLEs. Some convec-

tive regimes, such as supercells, have yet to be observed producing many TLEs and

the few TLEs are mostly confined to any stratiform precipitation region that may

develop during the late mature and decaying stages. Furthermore, the vast majority

of þCGs, even many with peak currents above 50 kA, produce neither sprites nor

elves, which are detectable using standard LLTV systems. While large peak current

8 IMPACTS OF LIGHTNING UPON THE MIDDLE ATMOSPHERE 423

þCGs populate both MCSs and supercells, only certain þCGs possess character-

istics that generate sprites or elves.

Monitoring ELF radio emissions in the Schumann resonance bands (8 to 120 Hz)

has provided a clue to what differentiates the TLE parent CG from ‘‘normal’’ flashes.

The background Schumann resonance signal is produced from the multitude of

lightning flashes occurring worldwide. It is generally a slowly varying signal, but

occasionally brief amplitude spikes, called Q-bursts, are noted. Their origin was

a matter of conjecture for several decades. In 1994, visual sprite observations at

Yucca Ridge were coordinated in real time with ELF trans ients (Q-bursts) detected

at a Rhode Island receiver station operated by the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology (Boccippio et al., 1995). This experiment, repeated many times since,

clearly demonstrated that Q-bursts are companions to the þCG flashes generating

both sprites and elves. ELF measurements have shown that sprite parent þCGs are

associated with exceptionally large charge moments (300 to > 2000 C-km). The

sprite þCG ELF waveform spectral color is ‘‘red,’’ that is, peaked toward the funda-

mental Schumann resonance mode at 8 Hz. Lightning charge transfers of hundreds

of coulombs may be required for co nsistency with theories for sprite optical intensity

and to account for the ELF Q-burst intensity. Lightning causal to elves has a

much flatter (‘‘white’’) ELF spectrum, and though associated with the very highest

peak current þCGs (often > 150 kA), exhibits much smaller charge moments

( < 300 C-km) (Huang et al., 1999).

Recent studies of High Plains MCSs confirm that their electrical and lightning

characteristics are radically different from the textbook ‘‘dipole’’ thunderstorm

model, derived largely from studies of rather small convective storms. Several hori-

zontal laminae of positive charge are found, one often near the 0

C layer, and these

structures persist for several hours over spatial scales of 100 km. With positive

charge densities of 1 to 3 nC=m

3

, even relatively shallow layers (order 500 m) cover-

ing 10

4

to 10

5

km

2

can contain thousands of coulombs. Some 75 years ago,

C.T.R. Wilson (1956) postulated that large charge transfers and particularly large

charge moments from CG lightning appear to be a necess ary condition for conven-

tional breakdown that could produce middle atmospheric optical emissions. Sprites

occur most readily above MCS stratiform precipitation regions with radar echo areas

larger than 10

4

km

2

. It is not uncommon to observe rapid-fire sequences of sprites

propagating above storm tops, apparently in synchrony wi th a large underlying

horizontal lightning discharge. One such ‘‘dancer ’’ included a succession of eight

individual sprites within 700 ms along a 200-km-long corridor. This suggests a

propagation speed of the underlying ‘‘forcing function’’ of 3 10

5

m=s. This is

consistent with the propaga tion speed of ‘‘spider’’ lightning—vast horizontal dendri-

tic channels tapping extensive charge pools once a þCG channel with a long conti-

nuing current becomes established (Williams, 1998).

It is suspected that only the larger MCS, which contain large stra tiform precipita-

tion regions, give rise to the þCGs associated with the spider lightning networks

able to lower the necessary charge to ground. The majority of sprite parent þCGs are

concentrated in the trailing MCS stratiform regions. The radar reflectivities asso-

ciated with the parent þ CGs are relatively modest, 30 to 40 dBZ or less. Only a

424 ATMOSPHERIC ELECTRICITY AND LIGHTNING

small subregion of trailing stratiform area produces sprite and elves. It would appear

that this portion of the MCS possesses, for several hours, the requisite dynamical and

microphysical processes favorable for the unique electrical discharges, which drive

TLEs. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the relationships between lightning and the major

TLE types

9 THEORIES ON TRAN SIENT LUMINOUS EVENTS

Transient luminous events have captured the interest of many theoreticians

(Rowland, 1998; Pasko et al., 1995). Several basic mechanisms have been postulated

to explain the observed luminous structures. These include sprite excitation by a

quasi-electrostatic (QE) mechanism. Sprite production by runaway electrons in the

strong electric field above storms has been suggested. The formation of elves from

lightning electromagnetic pulses (EMP) is now generally accepted. More than one

mechanism may be operating, but on different temporal and spatial scales, which in

turn produce the bewildering variety of TLE shapes and sizes. Absent from almost

all theoretical modeling efforts are specific data on key parameters characterizing

lightning flashes that actually produce TLEs. Many modelers refer to standard

reference texts, which, in turn, tend to compile data taken in storm types and locales

that are not representative of the nocturnal High Plains. Specifically, many invoke

the conventional view that the positive charge reservoir for the lightning is found in

the upper portion of the cloud at altitudes of 10 km. But the positive dipole (or

tripole) storm model has been found wanting in many mid continental storms. We

surveyed the range of lightning parameters used in over a dozen theoretical modeling

studies. While the proposed heights of the vertical þCG channel ranges from 4 to

20 km, there is a clear preference for 10 km and above. The amount of charge

lowered varies over three orders of magnitude, as does the time scale over which

the charge transfer occurs. Only a few studies consider the possible role of horizontal

TABLE 1 Current Ideas on TLE Storm=Lightning Parameters in Selected Storm

Types

Core of Supercells

a

MCS Stratiform

Region

‘‘Ordinary’’

Convection

þCG peak currents > 40 kA > 60 kA 30 kA

Storm dimension 10–20 km 10–500 km <20–100 km

Spider discharges Few=small Many=large Some

Continuing current Short if any Longest, strongest Low intensity

þCG channel height 10–15 km (?) 5 km (?) 10 km (?)

Sprites occur? No (except at end) Many Rare (?)

Elves occur? No (except at end) Many Rare (?)

Blue jets occur? Yes (?) Rare (?) Rare (?)

a

Some supercells may generate a few sprites during their final phase when=if extensive stratiform

develops.

9 THEORIES ON TRANSIENT LUMINOUS EVENTS 425