Perrie M. (ed.) The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a. p. pavlov

duma and the Moscow nobility.

10

The court retained its aristocratic compo-

sition throughout the years of Godunov’s rule, both as regent and as tsar. At

the same time, at the end of the sixteenth century and at the beginning of

the seventeenth century there was a marked numerical increase in the provin-

cial nobility and a growth in its political activity. The provincial nobility was,

however, largely excluded from participation in governance. The highest posts

in the state apparatus were concentrated in the hands of the predominantly

aristocratic elites of the sovereign’s court, and also of the secretarial heads of

the chancellery bureaucracy. At the end of the sixteenth century the role of

the boyars in the governance of the central and local administrative apparatus

increased; the boyars and the Moscow nobles played a more noticeable part

than before in the work of the chancelleries, and the power of the provin-

cial governors was strengthened. In the years of Godunov’s regency we can

clearly observe the consolidation of the ‘boyar’ elite, both at court and in the

chancellery secretariat, into a special privileged ruling group of servitors.

This consolidation did not, however, lead to any weakening of the power of

the autocrat. By the end of the sixteenth century the princely-boyar elite had

lost most of their hereditary lands and their previous links with the provincial

nobility, and they did not constitute any kind of stratum of great magnates

who were all-powerful in the localities. The Russian aristocracy was totally

dependent on state service, and it was riven by precedence disputes; it was

incapable of acting as a united force in defence of its corporate interests.

11

Many of even the most eminent princes sought the friendship of the powerful

regent Boris Godunov, who largely controlled service appointments and land

allocations, and they provided him with their support. Godunov did not need

to resort to disgrace and execution on a large scale in order to retain the

obedience of the elite. But he managed to avoid resorting to the methods of

the oprichnina mainlybecause he wasableto take advantageof the results of the

oprichnina itself and the achievements of the centralising policies of previous

Muscovite rulers.

One of the most important events of Godunov’s regency was the estab-

lishment of the Russian patriarchate in 1589. This helped to strengthen the

authority of the Russian sovereign and of the Russian Church both within the

country and beyond its borders. The introduction of the patriarchate led to

a further rapprochement of Church and state. It is revealing that the main

10 Boiarskie spiski poslednei chetverti XVI–nachala XVII v. i rospis’ russkogo voiska 1604g., comp.

S. P. Mordovina and A. L. Stanislavskii, pt. i (Moscow: TsGADA, 1979), pp. 104–76.

11 A. P. Pavlov, Gosudarev dvor i politicheskaia bor’ba pri Borise Godunove (1584–1605 gg.)

(St Petersburg: Nauka, 1992), pp. 202–3.

268

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Fedor Ivanovich and Boris Godunov (1584–1605)

role in the negotiations with Patriarch Jeremiah of Constantinople, when he

came to Russia to discuss the establishment of the patriarchate, was played

by representatives of the secular power – the regent, Boris Godunov, and

the conciliar ambassadorial secretary, A. Ia. Shchelkalov.

12

At the same time, at

the end of the sixteenth century the clergy came to play an increasingly active

role in defending the interests of the state. For example, the leaders of the

Church hierarchy played a prominent role in the election of Godunov as tsar

and the legitimisation of his autocratic power, and in the denunciation of the

First False Dmitrii as an impostor. Boris Godunov’s supporter Metropolitan

Iov became patriarch, and other Church leaders were promoted. They largely

owed the strengthening of their position to the regent.

By implementing this policy of consolidating the upper tiers of the service

class and of the clergy under the aegis of the autocracy, Boris Godunov man-

aged to resolve the country’s internal political crisis, to restore the authority

of the Russian monarchy and to establish himself firmly in power.

With the aim of strengthening state power, Godunov’s government carried

out a restructuring of central and local institutions of government. At the

end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth, further

measures were introduced to improve and extend the chancellery system of

administration, and the number of secretaries was expanded.

13

The control

of the centre over the districts was again perceptibly increased. An important

indicator of this was the development and consolidation of the power of the

provincial governors (voevody).A new featurein this period wasthe appearance

of governors not only in the peripheral border towns, but also in the northern

and central regions of the country.

14

At the same time, we find a decline in

the role of the guba and zemskii (‘land’) institutions of local self-government

by the social estates.

In the realm of foreign policy, Boris Godunov’s government aimed to over-

come the onerous consequences of the Livonian war and to restore the inter-

national prestige of the Muscovite state. After the death of Ivan the Terrible,

Russian diplomats conducted tense negotiations with the Poles, as a result of

which they managed to prevent a potentially damaging military confronta-

tion with Poland and to conclude a prolonged fifteen-year truce, which was

extended for a further twenty years in 1601. Taking advantage of a favourable

12 A. Ia. Shpakov, Gosudarstvo i tserkov’ v ikh vzaimnykh otnosheniiakh v Moskovskom gosu-

darstve (Odessa: Tipografiia Aktsionernogo Iuzhno-russkogo obshchestva pechatnogo

dela, 1912), pp. 245–341; R. G. Skrynnikov, Gosudarstvo i tserkov’ na Rusi XIV–XVI vv.

(Novosibirsk: Nauka, 1991), pp. 351–61.

13 A. P. Pavlov, ‘Prikazy i prikaznaia biurokratiia (1584–1605 gg.)’, IZ 116 (1988): 187–227.

14 Pavlov, Gosudarev dvor,pp.239–49.

269

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

a. p. pavlov

international situation and of internal difficulties in Sweden, in the winter

of 1589/90 Russia began military action against the Swedes, with the aim of

regainingher former townson the Baltic coast. In 1595 in the village of Tiavzino

a peace treaty was signed with the Swedes,in which Sweden returned to Russia

Ivangorod, Iam, Kopor’e, Oreshek and Korela. This was a major victory for

Russia, although it should not be overstated – the problem of an outlet to the

Baltic Sea was not fundamentally resolved, and the sea-route known as the

‘Narva sailing’ remained in Swedish hands.

15

Russia’s trade with the countries

of Western Europe was conducted, as before, mainly through the north of the

country. As a result of Godunov’s efforts, relations with England were revived.

The Russian government extended its patronage to the English merchants and

gave them tariff privileges, but it refused to grant them monopoly rights to

trade through the White Sea and opened its ports to the merchants of other

countries.

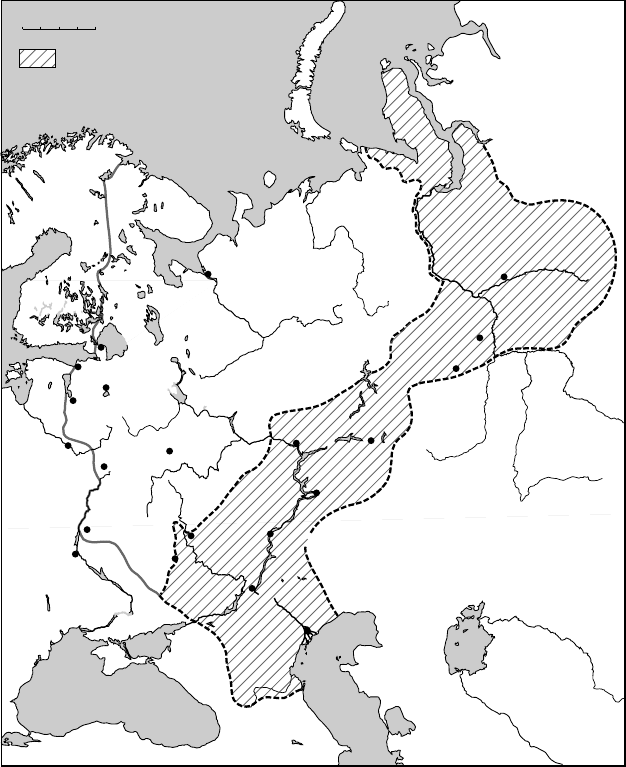

If in the west Moscow had managed to stabilise the situation, then in the

east and south its policy was more active and aggressive. One of Russia’s main

foreign-policy successes under Boris Godunov was the final consolidation of

its control over Siberia. After the death of Ermak Siberia had again come

under the power of the local khans. At the beginning of 1586 government

forces headed by the commander V. B. Sukin were sent beyond the Urals.

The Russian generals did not engage solely in military actions and organised

the construction of a whole network of fortified towns in Siberia. In 1588 the

Siberian khan Seid-Akhmat was taken prisoner, and ten years later the Russian

generals routed the horde of KhanKuchum. At the end of the sixteenthcentury

the vast and wealthy territory of Siberia became an integral part of the Russian

state (see Map 11.1).

Russia’s position on the Volga was considerably strengthened. In the 1580s

and 1590s a number of new towns were built – Ufa, Samara, Tsaritsyn, Sara-

tov and others. The consolidation of Russian influence on the Volga led the

khans of the Great Nogai Horde to recognise the power of the Muscovite

sovereigns. An entire system of fortified towns (Voronezh, Livny, Elets, Kursk,

Belgorod, Kromy, Oskol, Valuiki and Tsarev Borisov) was also built on the

‘Crimeanfrontier’.Theborders of the state wereextendedmuchfurthersouth.

The international situation was favourable for Russia’s southward expansion.

The Crimean Horde had been drawn into numerous wars on the side of

Turkey against Persia, the Habsburgsand the Rzeczpospolita, and it did not have

15 B. N. Floria, Russko-pol’skie otnosheniia i baltiiskii vopros v kontse XVI–nachale XVII v.

(Moscow: Nauka, 1973), pp. 61–2.

270

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Fedor Ivanovich and Boris Godunov (1584–1605)

0 400 km

Moscow

Novgorod

Archangel

N

.

D

v

i

n

a

U

R

A

L

M

T

S

Kiev

Don

Black Sea

Polotsk

Territory acquired

since 1533

C

A

U

C

A

S

U

S

M

T

S

Smolensk

Pskov

Ivangorod

Korela

T

er

e

k

Chernigov

V

o

lg

a

Kazan’

Samara

Belgorod

C

R

I

M

E

A

N

K

H

A

N

A

T

E

C

a

s

p

i

a

n

S

e

a

L

I

T

H

U

A

N

I

A

S

W

E

D

E

N

FINLAND

Voronezh

Tsaritsyn

Saratov

Ufa

Tiumen’

Tobol’sk

Ob

Surgut

SIBERIA

NOGAI

HORDE

Astrakhan’

Baltic

Sea

TURKEY

Map 11.1. Russia in 1598

sufficient forces to undertake any major campaign against Rus’. Only on one

occasion in the combined period of Godunov’s regency and reign did the

Crimeans manage to penetrate far into the Russian interior. In the summer of

1591 Khan Kazy-Girey came as far as Moscow with a large army. But having

encountered a substantial Russian force blocking his advance, he decided not

to risk the main body of his troops in battle, and was obliged to retreat.

271

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

a. p. pavlov

The period of Boris Godunov’s regency marked an important stage

in the development of cultural contacts with the countries of Western

Europe. Godunov was keen to recruit foreign specialists into Russian service.

Seventeenth-century Russian writers even accused him of excessive fondness

for foreigners. Boris himself had not had the opportunity to receive a system-

atic ‘book-learning’ education in his youth, but he gave his son Fedor a good

education. Endowed with a lively and practical mind, Boris Godunov was

no stranger to European enlightenment and he cherished plans to introduce

European-style schools into Russia. In order to train up an educated elite,

he sent groups of young people – the sons of noblemen and officials – to be

educated abroad.

Overcoming the economic collapse and the acute social crisis was a task of

primary importance and complexity. The central problem of internal policy

at the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth centuries was

to satisfy the economic interests of the noble servicemen (at that time the

cavalry, comprising the service-tenure nobility, constituted the fighting core of

the Russian army). In the first year of the reign of Tsar Fedor Ivanovich (on 20

July 1584)thegovernment gottheChurchcounciltoapprovearesolutionwhich

confirmed a previous decision of 1580 forbidding land bequests to monasteries,

and introduced an important new point abolishing the tax privileges (tarkhany)

of large-scale ecclesiastical and secular landowners.

16

Encountering opposition

from the Church authorities, however, Boris Godunov’s government chose

not to go for the complete abolition of the tarkhany and restricted itself to the

adoption of Ivan Groznyi’s practice of the 1580s of collecting extraordinary

taxes from ‘tax-exempt’ lands. The act of 1584 legalised this practice. The

council’s resolution forbidding land bequests to monasteries was also put into

practice in an inconsistent way. In the sources we find numerous cases of

the violation of this law.

17

The measures of the 1580s and 1590s did not halt the

growth of monastery landownership and did not fundamentally eliminate the

tax privileges of the large landowners. They did not really guarantee either

the uniformity of taxation or the creation of a supplementary fund of land for

allocation as service estates. Moreover, the government continued to make

extensive land grants to monasteries and to prominent boyars. Not wanting to

quarrel with the influential clergy, Godunov’s government tried to minimise

its concessions to the nobility at the expense of the monasteries.

16 Zakonodatel’nye akty,p.62

17 S.B.Veselovskii, Feodal’noe zemlevladenie v severo-vostochnoi Rusi (Moscow and Leningrad:

AN SSSR, 1947), p. 107.

272

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Fedor Ivanovich and Boris Godunov (1584–1605)

The most important measure designed to satisfy the interests of the nobil-

ity was the issuing and implementation of laws about the enserfment of the

peasants. Boris Godunov’s government at first continued the practice of the

so-called ‘forbidden years’, which had been introduced in Ivan Groznyi’s reign

at the beginning of the 1580s (‘forbidden years’ were years in which peasants

were deprived of their traditional right to leave their landlords on St George’s

Day). In the 1580s and 1590s a district land census was undertaken. However,

the land census of the end of the sixteenth century did not have such a compre-

hensive character as is usually assumed. The absence of complete up-to-date

surveys of many regions delayed the process of peasant enserfment. The prac-

tice of ‘forbidden years’ was not in itself sufficiently effective to retain the

peasant population in place. It contained a number of contradictions. On the

one hand, the landowner had the right to search for his peasants throughout

the entire period of operation of the ‘forbidden years’, and the duration of

the search period was not stipulated; on the other, the regime of ‘forbidden

years’ was regarded as a temporary measure – ‘until the sovereign’s decree’.

In addition, the ‘forbidden years’ were not introduced simultaneously across

the whole territory of the country, and this introduced further confusion

into judicial transactions. After 1592 the term, ‘forbidden years’, disappears

from the sources. V. I. Koretskii expressed the opinion that in 1592/3 a sin-

gle all-Russian law forbidding peasant movement was introduced.

18

But other

scholarshave expressedserious doubts as towhethersuchamajorlawofenserf-

ment existed.

19

Great interest has been aroused by documents discovered by

Koretskii which contain information about the introduction at the beginning

of the 1590s of a five-year limit on the presentation of petitions about abducted

peasants. By establishing a definite five-year limit for the return of peasants the

government was trying to introduce some kind of order into the extremely

confused relationships among landowners in the issue of peasant ownership.

The new practice annulled the old system of ‘forbidden years’ and negated

the significance of the district land-survey, which remained incomplete in the

1580s and early 1590s, although it had arisen out of the recognition of the fact of

the prohibition of peasant transfers. The policies of the early 1590s described

above were developed further in a decree of 24 November 1597, which is the

earliest surviving law on peasant enserfment. According to this decree, in the

18 V. I. Koretskii, Zakreposhchenie krest’ian i klassovaia bor’ba v Rossii vo vtoroi polovine XVI v.

(Moscow: Nauka, 1970), pp. 123ff.

19 V. M. Paneiakh, ‘Zakreposhchenie krest’ian v XVI v.: novye materialy, kontseptsii, per-

spektivy izucheniia (po povodu knigi V. I. Koretskogo)’, Istoriia SSSR, 1972,no.1: 157–65;

R. G. Skrynnikov, ‘Zapovednye i urochnye gody tsaria Fedora’, Istoriia SSSR, 1973,no.1:

99–129.

273

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

a. p. pavlov

course of a five-year period fugitive and abducted peasants were subject to

search and return to their former owners, but after the expiry of these five

‘fixed’ years they were bound to their new owners. The introduction of the

norm of a five-year search period for peasants was advantageous primarily for

the large-scale and privileged landowners, who had greater opportunities to

lure peasants and to conceal them on their estates.

Alongside these measures relating to the enserfment of the peasants, legis-

lation was enacted at the end of the sixteenth century concerning slaves. The

most important law on slavery was the code (Ulozhenie)of1 February 1597

which required the compulsory registration of the names of slaves in special

bondage books. According to the code of 1597 debt-slaves (kabal’nye liudi)were

deprived of the right to obtain their freedom by paying off their debt, and

were obliged to remain in a situation of dependency until the death of their

master. The law prescribed that deeds of servitude (sluzhilye kabaly) should be

taken from ‘free people’ who served their master for more than six months,

thereby turning them into bond-slaves. Thus slave-owners acquired the pos-

sibility of enslaving a significant number of ‘voluntary servants’, and thereby

compensating significantly for the labour shortage.

Boris Godunov’s government was thus greatly concerned to satisfy the

economic needs of the nobility. But at the same time, in trying to secure the

support of the influential boyars and clergy, Godunov clearly did not intend

to cause serious damage to their interests in order to please the rank-and-file

nobility, and this explains the notorious inconsistency of his ‘pro-noble’ policy.

In the towns Godunov’s government conducted a policy of so-called

‘trading-quarter construction’, which satisfied the economic interests of the

townspeople, since the ‘tax-paying (tiaglye) traders’ (those townspeople who

paid state taxes) included artisans and tradesmen who belonged to monaster-

ies and to servicemen. But at the same time, ‘trading-quarter construction’

was implemented by coercive methods and it led to a greater binding of the

townsmen to the trading quarters.

20

The government’s economic policy, together with the securing of peace on

its borders, soon bore fruit, and in the 1590s the economy revived significantly.

At the end of the 1580s and the beginning of the 1590s the tax burden was

also reduced to some extent.

21

Contemporaries are unanimous that the reign

of Fedor Ivanovich was a period of stability and prosperity. Boris Godunov

deservesmuch of the credit for this. ‘Boris is incomparable’,the Russianenvoys

20 P. P. Smirnov, Posadskie liudi i ikh klassovaia bor’ba do serediny XVII veka, 2 vols. (Moscow

and Leningrad: AN SSSR, 1947–8), vol. i (1947), pp. 160–90.

21 Kolycheva, Agrarnyi stroi,p.168.

274

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Fedor Ivanovich and Boris Godunov (1584–1605)

to Persia said, referring not only to the regent’s remarkable intelligence, but

also to his unique role in government. At the end of the 1580s Godunov

acquired the right to deal independently with foreign powers. He buttressed

his exceptional position with a number of high-sounding titles. In addition

to the rank of equerry which he had obtained in 1584 he also called himself

‘vicegerent and warden’ of the khanates of Kazan’ and Astrakhan’ and ‘court

[privy] governor’, and he adopted the title of ‘servant’. Russian envoys to

foreign courts explained this last title as follows: ‘That title is higher than all

the boyars and is granted by the sovereign for special services.’

22

Slowly but surely, Godunov rose to the summit of power, which he reached

by carefully calculated moves. He did not resort to disgrace and bloodshed on

any significant scale. In the entire period of his rule, both as regent and as tsar,

not a single boyar was executed in public. But Boris was by no means a meek

and kindly person. He was both cunning and ruthless in his dealings with his

most dangerous opponents. His reprisals against his enemies were clandestine

and pre-emptive. The chancellor P. I. Golovin was secretly murdered en route

to exile, evidently not without Godunov’s knowledge.

23

Boris also disposed

covertlyof the Princes Ivan Petrovichand AndreiIvanovichShuiskii. He played

a skilful political game, planning his moves well in advance and eliminating

not only immediate but also potential rivals. For example, with the help of a

trusted associate – the Englishman Jerome Horsey – Godunov persuaded the

widow of the Livonian ‘king’ Magnus, Mariia Vladimirovna (the daughter of

Vladimir Staritskii and Evdokiia Nagaia), to come back to Russia. But when

she returned, Mariia and her young daughter ended up in a convent.

In May 1591 Tsarevich Dmitrii, the youngest son of Ivan the Terrible, died in

mysterious circumstances at Uglich. The inhabitants of Uglich, incited by the

tsarevich’s kinsmen, the Nagois, staged a disturbance and killed the secretary

Mikhail Bitiagovskii (who was the representative of the Moscow administra-

tion in Uglich), together with his son and some other men whom they held

responsible for the tsarevich’s death. Soon afterwards a commission of inquiry,

headed by Prince V. I. Shuiskii, came to the town from Moscow. It reached the

conclusion that the tsarevich had stabbed himself with his knife in the course

of an epileptic fit. But the version that Dmitrii had been killed on the orders

of Boris Godunov enjoyed wide currency among the people. In the reign of

22 G. N. Anpilogov, Novye dokumenty o Rossii kontsa XVI–nachala XVII veka (Moscow: Izda-

tel’stvo Moskovskogo universiteta, 1967), pp. 77–8.

23 Dzherom Gorsei, Zapiski o Rossii: XVI–nachalo XVII v. (Moscow: MGU, 1990), p. 101;cf.

Lloyd E. Berry and Robert O. Crummey (eds.), Rude and Barbarous Kingdom: Russia

in the Accounts of Sixteenth-Century English Voyagers (Madison, Milwaukee and London:

University of Wisconsin Press, 1968), p. 322.

275

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

a. p. pavlov

Tsar Vasilii Shuiskii this version received the official sanction of the Church

when Dmitrii of Uglich was canonised as a saint. For a long time the view that

Boris Godunov was responsible for the tsarevich’s death was unchallenged in

the historical literature. The situation changed after the publication of stud-

ies by S. F. Platonov and V. K. Klein.

24

Platonov traced the literary history of

the legend about Tsarevich Dmitrii’s ‘murder’ and noted that contemporaries

who wrote about it during the Time of Troubles refer in very circumspect

terms to Boris’s role in the killing of Dmitrii, and that dramatic details of the

murder appear only in later seventeenth-century accounts. Klein carried out

extensive and fruitful work examining and reconstructing the report of the

Uglich investigation of 1591. He demonstrated that what has come down to

us is the original version, in the form in which it was presented by Vasilii

Shuiskii’s commission of inquiry to a session of the Sacred Council on 2 June

1591 (only the first part of the report is missing). The version contained in the

investigation report has received the support of I. A. Golubtsov, I. I. Polosin,

R. G. Skrynnikov and other historians.

25

But doubts concerning the validity

of the way the investigation report was compiled have still not been dispelled.

A. A. Zimin made a number of serious criticisms of this source.

26

The inves-

tigation report is undoubtedly tendentious. But its critics have not managed

to advance arguments which would decisively refute the conclusions of the

commission of inquiry. The sources are such that the indictment against Boris

remains unproven; but neither does the case for the defence give him a com-

plete alibi.

Would the death of the tsarevich have been in Godunov’s interests? It is

difficult to give an unambiguous answer to this question. On the one hand,

the existence of a centre of opposition at Uglich, with Tsarevich Dmitrii as

its figurehead, could not have failed to arouse the regent’s anxiety. But, on

the other hand, Boris could have achieved ‘supreme power’ without killing

the tsarevich. Dmitrii had been born from an uncanonical seventh marriage,

which enabled Godunov to question his right to the throne. At the same

time Boris took pains to enhance the status of his sister, Tsaritsa Irina, as a

possible heir to the throne. In a situation where Boris Godunov was the de

facto sole ruler of the state, Tsar Fedor’s ‘lawful wife in the eyes of God’ could

quite justifiably challenge the right to the throne of Tsar Ivan’s son, born ‘of an

24 S. F. Platonov, Boris Godunov (Petrograd: Ogni, 1921), pp. 96–7; V. K. Klein, Uglichskoe

sledstvennoe delo o smerti tsarevicha Dimitriia (Moscow: Imperatorskii Arkheologicheskii

institut imeni Imperatora Nikolaia II, 1913).

25 I. A. Golubtsov, ‘ “Izmena” Nagikh ’, Uchenye zapiski instituta istorii RANION, 4 (1929): 70

etc.; Skrynnikov, Rossiia nakanune ‘Smutnogo vremeni’,pp.74–85.

26 A. A. Zimin, V kanun groznykh potriasenii (Moscow: Mysl’, 1986), pp. 153–82.

276

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Fedor Ivanovich and Boris Godunov (1584–1605)

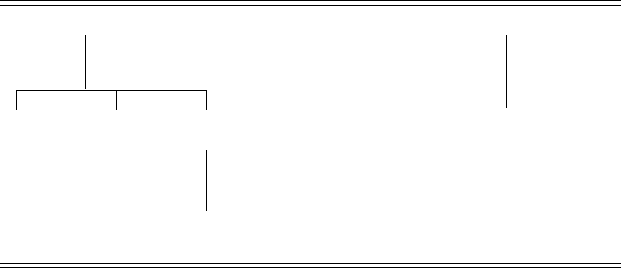

Table 11.1.

The end of the Riurikid dynasty

IVAN IV m. (1) Anastasiia Romanovna .......................................m. (7) Mariia Nagaia

1530–84

Dmitrii

1552–3

Ivan

1554–81

FEDOR m. Irina Godunova

1557–98

Dmitrii (of Uglich)

1582–91

Fedos’ia

1592–4

unlawful seventh wife’. It is quite possible that Godunov was hatching some

kind of plan to dispose of the tsarevich and his kin.

27

But if he had intended

to murder Dmitrii, May 1591 was not the most appropriate time to make the

attempt. In April and May there was worrying news that the Crimean khan

was preparing to invade, and things were not entirely calm in the capital in the

spring of 1591. In general we do not have sufficiently strong arguments either

to reject or to confirm the findings of the report of the Uglich investigation,

and the question of the circumstances of Tsarevich Dmitrii’s death remains an

open one.

In May 1592 the court ceremoniously celebrated the birth of a daughter –

Tsarevna Fedos’ia – to Tsar Fedor and Tsaritsa Irina. But the tsarevna died on

25 January 1594, before her second birthday (see Table 11.1). Her death clearly

revealed that the ruling dynasty was facing a crisis, and it made the question of

the succession urgent. The Godunovs blatantly promoted their claims to the

throne. From the middle of the 1590s Boris began to involve his son Fedor in

affairs of state. But Boris Godunov was not the only candidate for the throne.

His former allies, the Romanovs, stood in his way. Their advantage lay in the

fact that Tsar Fedor himself had Romanov blood (from Tsar Ivan’s marriage to

Anastasiia Romanovna). As Fedor’s brother-in-law, Boris Godunov could not

boast a blood relationship with the tsar. Gradually the Romanovs advanced

themselves at court and acquired influential positions in the duma. Around

them there gathered a close-knit circle of their kinsmen and supporters. From

27 Dzhil’s Fletcher, O gosudarstve Russkom (St Petersburg: A. S. Suvorin, 1906), p. 21; cf.Berry

and Crummey, Rude and Barbarous Kingdom,p.128.

277

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008