Pavlac B.A. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities throughout History

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

276

CHAPTER 12

even drew on the culture of the new lands and showed appreciation for some of

the art, artifacts, and literature of ‘‘Orientals’’ and Africans.

On the other hand, Europeans blithely ignored the exploitation, cruelty, and

hopelessness created by their supremacy. Many native peoples suffered humilia-

tion, defeat, and death. Although their health and standard of living often improved

because of participation in global trade, colonial peoples suffered from the conse-

quences of business decisions made in distant lands. These global economic bonds

only intensified with time. Natives often felt like prisoners in their own countries

as traditional social status and customs vanished. Europeans justifiably outlawed

widow burning in India while ignoring how their own policies impoverished many

other widows and families. Most of the peoples of the world had been fine without

Western colonialism before the nineteenth century. No sooner had they been subju-

gated than many were working to regain their autonomy. Within a few decades,

they would succeed.

Review: How did the Europeans come to dominate Africa and Asia?

Response:

FROM SEA TO SHINING SEA

While Europeans added to their empires, a new Western power was rising, unsus-

pected, in the Western Hemisphere. The United States of America, like Russia

before it, initially aimed its imperialism not across oceans, but across its own conti-

nental landmass. The peace agreement with Britain after the War of Independence

granted the Americans most lands east of the Mississippi River, giving the United

States a size comparable to western Europe. Many Americans believed it was their

obvious national purpose, or manifest destiny, to dominate North America.

Some acquisitions came relatively peacefully. No ‘‘Americans’’ lived west of the

Mississippi in 1803. In that year, Napoleon sold the Louisiana Purchase to the

United States, giving the new nation its first significant expansion. Neither govern-

ment in Paris or Washington D.C., of course, consulted with the natives about who

owned the land. After a second attempt to conquer Canada in the War of 1812

PAGE 276.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:31:56 PS

THE WESTERNER’S BURDEN

277

failed, the Americans peacefully negotiated away any rivalry with Britain over

mutual borders in the north of Maine or the Oregon Territory. The United States

also bought Florida from Spain.

The newly independent Mexico was another matter. American immigrants who

had moved into Mexico’s province of Texas successfully rebelled in 1836, after Mex-

ico tried to outlaw slavery. At first, the United States was reluctant to annex Texas.

A decade later, though, the activist President Polk did so. Armed troops shooting at

one another over disputed borders triggered the Mexican-American War (1846–

1848). The United States was quickly victorious and briefly considered, but

rejected, taking over all of Mexico. Instead, the Yankees only confiscated a third of

Mexico’s territory, leaving it as the United States’ weak southern neighbor.

Meanwhile, the Indians, or Native American peoples, stood in the way of the

United States’ unquestioned supremacy of America. Most Indians had been killed

or removed from the original thirteen colonies before the American War of Inde-

pendence. In the 1830s, Indian removals forced nearly all of those who had

remained east of the Mississippi River into reservations on the other side, even

though some tried to defend their treaty rights in U.S. courts. Next, Americans

migrated westward to the Pacific Coast, crossing the Great Plains, which had been

acquired in the Louisiana Purchase, and the Southwest, which had been won from

Mexico. Americans rapidly broke all treaties signed with Indian tribes. In a series of

Plains Indian Wars (1862–1890), superior Western technology and numbers gave

the ‘‘cowboys’’ victory over the Indians.

In the popular imagination of Western civilization, images of these conflicts

were colored with contradictions. ‘‘Noble savages’’ might seem to be either tragic

heroes untainted by the flaws of civilization or barbaric ‘‘redskin’’ murderers. ‘‘Civi-

lized’’ men and women on the frontier might either nobly embody liberty and self-

reliance to tame the wilderness or ruthlessly exterminate even women and children

to steal Indian land. In the real world, by the end of the nineteenth century, Euro-

pean Americans in both the United States and Canada had killed most Native Ameri-

cans and confined the remnants to the near-worthless reservations.

As they finished their domination of the natives, some Americans began to con-

sider whether manifest destiny extended beyond the shores of North America. Since

1823, the United States (with the support of the United Kingdom of Great Britain)

had upheld the Monroe Doctrine, which prevented the Europeans from reintroduc-

ing colonial imperialism to Latin America (see the next section). Increasingly,

though, the United States began to see the Western Hemisphere as its own imperial-

ist economic sphere.

The United States gained strength through its industrialization, while Latin

America remained largely agricultural. Soon U.S. merchants and politicians applied

the dollar diplomacy, or using American economic power, whether through bribery,

awarding of contracts, or extorting trade agreements, to influence the decisions of

Latin American regimes. Obedience to Western capitalists earned Central American

governments the nickname ‘‘banana republics.’’ At the end of the nineteenth cen-

tury, American corporations imported bananas, which originated in Southeast Asia,

to cultivate in Central America. Under the American business plan, peasants who

PAGE 277.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:31:57 PS

278

CHAPTER 12

had grown corn to feed their families instead became laborers who harvested

bananas to feed foreigners. If workers in Caribbean or Central American states

resisted, the northern giant would send troops to occupy them and protect Ameri-

can property and trade. American armies in countries like Haiti and Nicaragua then

propped up corrupt dictators who exploited their people but maintained friendly

relations with the ‘‘big brother’’ to the north.

At the same time, U.S. interests looked to profit in the Pacific. America’s first

major victim was Japan, which almost suffered the same fate as its exploited Asian

neighbor, China. The cluster of islands that the Japanese called the Land of the

Rising Sun had maintained an isolationist policy for centuries. Since the early 1600s,

hereditary military dictators, called shoguns, lorded over a well-ordered, stable,

closed society in the name of powerless figurehead emperors. In the first age of

imperialism, Japan had tentatively welcomed contact with Western explorers, trad-

ers, and missionaries. The Tokugowa dynasty of shoguns, though, had then shut

the borders to Western influence by the late 1600s. After that, the Japanese permit-

ted one Dutch ship only once a year to enter the port of Nagasaki for international

trade. Otherwise, the Japanese wanted to be left alone.

That isolation ended in 1853 when American warships under the command of

Commodore Matthew C. Perry steamed into Tokyo Harbor. Perry demanded the

Japanese open trading relations with the United States or else he would open fire

with his modern guns. Ironically, the government of the Tokugawa shogun had

destroyed most firearms, leaving Japan defenseless. Fearful Japan signed a treaty

loaded with extraterritoriality exploitation, just as China had suffered. The British,

French, Russians, and all the others soon followed the Americans to share in the

spoils.

Despite this forced opening of its borders, Japan ended up doing something

few other non-Western countries could: it rapidly westernized. The Japanese

replaced the discredited Tokugawa shogun with the figurehead emperor during the

Meiji Restoration (1868). Then the Japanese traveled out into the world in droves

and learned from the West about what made its civilization so powerful. The British

taught the Japanese about constitutional monarchy and the navy. The Americans

trained them in modern business practices. The French enlightened them about

Western music and culture. The Germans drilled them on modern armies. Within a

generation, the Japanese revolutionized their country to make it almost like any

other Western power.

The name Meiji Restoration is a misnomer, however, since the Meiji dynasty

was not so much restored to power as transformed in purpose. Before the restora-

tion, the emperors had drifted through a shadowy, ineffective existence under the

shoguns (like the mikado of the contemporary Gilbert and Sullivan operetta). Now,

the emperor became a godlike figure who united Japanese religion with Japanese

patriotism, much like Alexander or Augustus had done for the Greeks and Romans.

This deified monarchy was the only unmodern move made by the Japanese. Other-

wise, Japan plunged into a relatively smooth Western revolution, easily crushing

the few samurai who resisted. Japan’s equivalent of the Commercial, Intellectual,

Scientific, Industrial, and English/American/French political Revolutions was all

PAGE 278.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:31:58 PS

THE WESTERNER’S BURDEN

279

accomplished in short order. The emperor’s subjects soon sought to honor him

with an empire, imitating what the British had done for their kings and queens.

Thus, the westernization of Japan had enormous consequences for the twentieth

century.

The United States went on an imperialistic spree at the turn of the twentieth

century. The Spanish-American War (1898) added Puerto Rico and the Philippines

as colonies and Cuba almost as a protectorate. President McKinley partly justified

the seizure of the Philippines with the need to convert the native islanders to Chris-

tianity. Ignorant Americans apparently did not know that most Filipinos were

already Roman Catholic. When many Filipinos fought back with a guerrilla war, U.S.

forces ended resistance by resorting to concentration camps. Hundreds of thou-

sands of Filipinos died of disease and malnutrition in the badly managed camps.

McKinley also annexed Hawaii, where American pineapple and sugarcane corpora-

tions had seized power from the native Queen Liliuokalani. The next president,

Theodore Roosevelt, suggested a corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, that the United

States would use force on behalf of European economic claims in Latin America

(thus keeping the European imperialists out). In 1903, when Colombia refused the

American offer to build a canal through its province of Panama, the United States

helped provincial leaders stage a rebellion. The new leaders of Panama gave control

of a canal zone to the United States. American know-how finished the Panama Canal

by 1913, although that extraordinary effort killed over five thousand workers

brought in from the Caribbean and Europe.

Such expansionist efforts showed how Americans could behave as badly as the

rest of the westerners. Most Americans, however, have usually seen themselves as

somehow different, confident in their rugged individualism, creative opportunism,

and eager mobility. This concept of moral superiority to our other Western and

world cultures is called American exceptionalism. It is similar to the common

Western exceptionalism that had supported imperialism since the Renaissance. The

American version views Americans as better than their fellow westerners. It

expresses feelings that manifest destiny reflects a God-given calling and that Ameri-

can motives are more pure and generous than those of contemporary imperialist

powers. Some historians have suggested that the United States does indeed differ

from European states due to its origins as a society of immigrants seeking freedom

and economic opportunities in an empty place with plenty of land and natural

resources (although Canada, Australia, and New Zealand offer comparable histor-

ies). History shows, however, that American success too often came from brutal

means to dominate that land and seize resources, a record which most Americans

do not acknowledge. It is no coincidence that the United States began its global

imperialism right after the Plains Indian Wars finally ended with the defeat of the

Native Americans. Most immigrant Americans were unaware of the consequences

of acquiring so much influence over so many peoples, first at home, then abroad;

they noticed only the benefits of growing wealth and prosperity. American imperial-

ism made the United States one of the leading Western powers by 1914, poised to

become the most powerful country in the world. But with power comes responsi-

bility, and the United States would only slowly come to learn this lesson in the

twentieth century.

PAGE 279.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:31:59 PS

280

CHAPTER 12

Review: How did the United States of America become a world power?

Response:

NATIONALISM’S CURSE

While imperialism cobbled together widespread empires, a new idea began to trans-

form politics in Europe. Opposition to the French domination of Europe partly

inspired the early advocates of nationalism. This idea decreed that states should

be organized exclusively around ethnic unities. Nationalists believed that a group

of people, called a nationality, is best served by having its own sovereign state. The

Industrial Revolution’s empowerment of the masses further affected the choices of

definition. Many nationalists argued that the masses of people from the bottom

up should define what makes a country, especially since the aristocratic and royal

dynasties who ruled from the top down often came from other ethnic groups. Some

dynasties, though, took the lead in nationalism, setting the terms for defining

nationalist characteristics. Nationalism’s earliest proponents hoped that it would

usher in an era of fraternal peace as different nations learned to respect one another

despite their cultural differences.

Tragically, the emphasis on nationalism instead has more often resulted in

increased international conflict. These clashes derive from a basic principle:

The greatest difficulty for nationalists was how to define

exactly who belonged or not.

Including some people in a group while throwing others out created tensions. Each

ethnic identity varies according to its definers. Ethnicity may be based on geo-

graphic location, shared history, ancestry, political loyalty, language, religion, fash-

ion, and any combination thereof. Language was often the starting point, as cultural

builders settled on one dialect and collected stories and songs that contributed to

a unique identity. In schools and academic institutes, in the theater and novels,

nationalists transmitted the supposed identity of a particular nationality. Political

PAGE 280.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:32:00 PS

THE WESTERNER’S BURDEN

281

history became a victorious story of destined greatness for the winners in state

building, or an ongoing grievance for the losers.

By definition, though, including some people in the group meant excluding

others. Some extreme nationalists even began arguing for the exclusionary ideolo-

gies of racism. The ideologies of racism asserted that some communities of

humans shared bloodlines (a special, imagined quality inherited from common

ancestors) that made them superior to others. Interest groups and political parties

soon organized around nationalist and racist ideas, embracing those who belonged

and hating those who did not.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, Metternich’s conservative decisions

at the Congress of Vienna dismissed nationalist dreams. Hopeful nationalists in turn

ignored the difficulties of ethnic diversity. Each of the five great powers included

many people who did not fit their ‘‘ethnic’’ name. In the Austrian Empire no one

ethnic group was in a majority, as Germans, Magyars, Italians, and Slavs (most

importantly Czechs, Slovaks, Croats, and Poles) vied for the attention of the Habs-

burg emperor. Russia included, among many others, the Asians in Siberia in the

east, Turks in the southeast, and Balts in the northwest, as well as the Slavic Poles

and Ukrainians in the west. Prussia did have a majority of Germans, but Roman

Catholics of the Rhineland felt no sense of ‘‘Prussianness,’’ nor did most Danes and

the large numbers of Poles and Wends (non-Polish Slavs in eastern Germany). Great

Britain locked many disgruntled Scots, Irish, and Welsh into a ‘‘United Kingdom’’

with the English. Even France, which might seem the most cohesive, had Basques

in the southwest, Bretons in the northwest, and Alsatian Germans in the east who

did not want to learn how to correctly pronounce patrie (‘‘fatherland’’). Most of

the smaller countries of Europe likewise lacked absolute ethnic homogeneity. Nev-

ertheless, nationalists simplistically complained: If the French have France, the

English have England, and even the Portuguese have Portugal, why shouldn’t our

ethnic group have Ethnicgroupland?

Surprisingly, the nationalist spirit first coalesced into reality across the Atlantic

Ocean. Haiti experienced the earliest nationalist movements. Between 1789 and

1804, slaves of African descent enjoyed a brief independence from French rule.

Soon afterward, the upper classes of European descent led the liberation of Latin

America (1810–1825) from colonial imperialism. The descendants of European

conquistadors and colonizers, known as Creoles (or criollos), slowly found their

interests diverging from the distant imperial mother countries of Spain and Portu-

gal. Many Creoles formed juntas, groups of elites who seized power. In 1811, the

most famous liberator, Simon Bolı

´

var (b. 1783–d. 1830), began to free Venezuela,

uniting it with neighboring Colombia. Meanwhile, Jose

´

de San Martı

´

n, ‘‘the Libera-

tor,’’ freed his homeland of Argentina along with Chile and began to fight for Peru.

San Martı

´

n retired, leaving Bolı

´

var to complete the independence of Peru and

Bolivia (later named after him). The success of other freedom fighters helped create

Mexico, the United Provinces of Central America, Paraguay, and Uruguay. By 1825,

very little remained of what had once been Spain’s vast empire in the Americas.

The leaders of these new Latin American nations did not have significant ethnic

differences from one another, except for geographic location. They all still spoke

the Spanish (or Portuguese in Brazil) of the mother country, wore the same style of

PAGE 281.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:32:00 PS

282

CHAPTER 12

clothing, practiced the same politics and economics, and worshipped as Roman

Catholics. Among the masses of Hispanic peasants, however, there was much diver-

sity. For example, Mexico had large numbers of mestizos (meaning of ‘‘mixed’’

Indian and European lineage), while Brazil had a much larger percentage of descen-

dants of African slaves. Each of the new countries had to deal with these ethnic

diversities.

To the north, the United States suffered its own major nationalist ethnic conflict

with the American Civil War (1861–1865). This war decided whether the United

States would survive united as one nation or divide into two or more countries.

The country’s very name, ‘‘United States,’’ revealed the ethnic divisions at its origin.

While some citizens called themselves American, more were likely to identify with

their state, as a Virginian or a New Yorker. The regional differences concerning

slavery sharpened the distinctions. Southerners, even those who were not slave-

holders, defended their ‘‘peculiar institution’’ because that was how Southerners

defined themselves. Under this pressure, the delicate balance among federal, state,

and individual rights broke down. In the war that followed, the northern Union

defeated the southern Confederacy because of the North’s superior numbers, its

technology, and President Abraham Lincoln’s determination. Still, the reaffirmed

federal unity did not entirely eliminate Southern ethnicity, since resentment still

festered more than a century later.

Back in western Europe, nationalism appealed to conservatives and their incli-

nation to look to the past for guidance. Indeed, nineteenth-century historians

began to collect and assemble imaginative histories of ethnic groups which they

argued were the forebears of modern nationalities. They collected source docu-

ments and organized them. Historians in those countries that represented a nation-

alist victory (for example, England or France) attributed success to cultural or racial

superiority. Even historians of ethnic groups excluded from power (for example,

the Irish or the Basques) adopted nationalistic perspectives, since they could glorify

some distant freedom that had been squelched by political tragedy or unjust con-

quest. The Romantic movement heavily contributed to these efforts. Nationalism

became a key political principle of Western civilization for both liberals and conser-

vatives. After the revolutions of 1848, conservatives adopted nationalism. Conserva-

tive leaders used Realpolitik, or pragmatic power politics, doing whatever it took

to achieve one’s goals (see table 12.1).

Italy was an early success for nationalism. Of course, there had never before

been a country called Italy, at least not like the one envisioned by its nationalist

proponents. Italian history began with Rome and its city-state, which quickly

became a multi-ethnic empire. In the Middle Ages, no single kingdom ever included

the entire peninsula. Since 1494, Italy had been dominated by foreign dynasties—

the French, the Spanish, and the Austrians—while the popes clung desperately to

their Papal States.

In the wake of the failed revolutions of 1848, many Italian nationalists called

for a Risorgimento (resurgence and revival) of an Italian nation-state. From 1848 to

1871 the Kingdom of Sardinia-Savoy-Piedmont spearheaded unification. Conserva-

tive prime minister Count Camillo di Cavour (r. 1852–1861) proposed a scheme

for unification to his absolute monarch, King Victor Emmanuel II. First, they would

PAGE 282.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:32:01 PS

THE WESTERNER’S BURDEN

283

Table 12.1. National Unifications in the Nineteenth Century

Kingdom of Sardinia-Savoy-

Piedmont Kingdom of Prussia

King Victor Emmanuel II King Wilhelm I Hohenzollern

Savoy

Prime Minister Camillo Chancellor Otto von Bismarck

di Cavour

Austro-Piedmontese War,

1859

Garibaldi’s Red Shirts conquer

Kingdom of Two Sicilies, 1860

Proclamation of Kingdom

of Italy in Turin

Danish War, 1864

Kingdom of Italy capital to

Florence, 1865

Seven Weeks War,

1866

Add Venice Northern German

Confederation

Franco-Prussian War,

1871–1872

Add Rome Add southern German states,

excluding Austria

Kingdom of Italy (Second) German Empire

Note: The unifications of Italy and Germany share similar developments and certain wars.

modernize and liberalize Sardinia-Savoy-Piedmont. Then, several well-planned mili-

tary actions would topple both Habsburgs in the north and the petty regimes in the

rest of the Italian Peninsula.

The scheme succeeded. The king graciously granted his own Kingdom of Sar-

dinia-Savoy-Piedmont a constitution and founded a parliament, which, weak as it

was, surpassed what most Italians had had before (namely, no legislatures at all).

The Piedmontese government built roads, schools, and hospitals. Other Italians

began to admire the little northern kingdom. Yet Cavour’s sponsorship of the

republican mercenary Giuseppe Garibaldi almost derailed the plan. In 1861, Gari-

baldi and his thousand volunteers, the ‘‘Red Shirts’’ (named after their minimalist

uniform), were supposed to invade Sicily and cause disturbances that would illus-

trate the need for Piedmontese leadership in Italian politics. Garibaldi swiftly con-

quered the island, but he then sailed to the mainland, where he took control of the

Kingdom of Naples and even marched on Rome itself. Piedmontese armies rushed

PAGE 283.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:32:01 PS

284

CHAPTER 12

south to meet him, and Cavour managed to convince Garibaldi to turn his winnings

into a united Kingdom of Italy.

From there, a few more tricks were required to round out the kingdom. Italy

bribed France by giving it the provinces of Savoy and Nice. In 1866, Italy, France,

and Prussia defeated the Habsburgs and forced them to surrender Lombardy and

Venice. The last major obstacle to Italian unity was the papacy. Popes had possessed

political power in central Italy since the fall of Rome in the fifth century. In 1870,

during the Franco-Prussian War, the French troops protecting the Papal States with-

drew. The Italians took control and made Rome the kingdom’s capital. The pope

resented this new Kingdom of Italy and forbade Roman Catholics to cooperate with

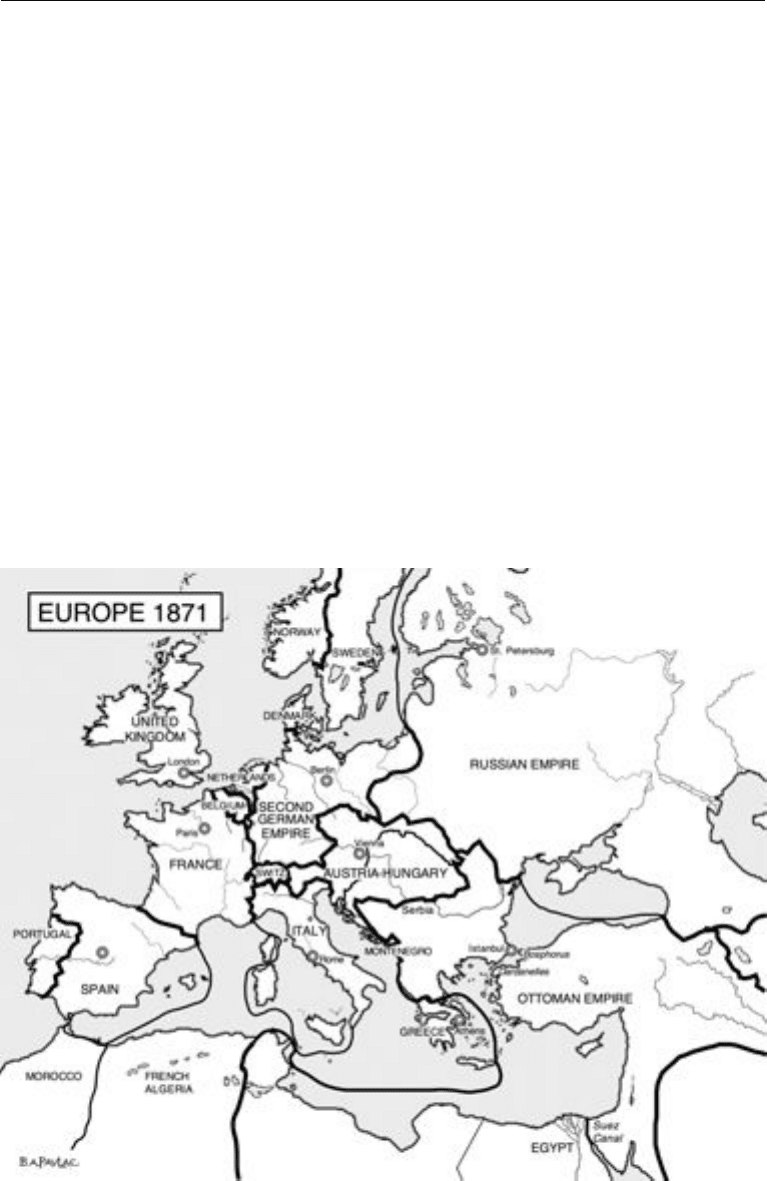

it. Nonetheless, Italy soon took its place among the great powers (see map 12.1).

The unification of Germany (1862–1871) saw a similar process. Unlike Italy,

there had actually been a united Germany back in the Middle Ages, but it had

quickly expanded into the Holy Roman Empire, which came to include northern

Italy, Burgundy, Bohemia, and the Lowlands. The Wars of the Coalitions had shat-

tered the Holy Roman Empire, but in 1815, a German confederation replaced it.

This confederation never functioned well, largely because of the rivalry over leader-

ship between Prussia and Austria. The liberal attempt to create a unified Germany

through the Frankfurt Parliament in 1848 failed completely.

The young Prussian aristocrat Otto von Bismarck liked neither the Frankfurt

Map 12.1. Europe, 1871

PAGE 284.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:32:29 PS

THE WESTERNER’S BURDEN

285

Parliament nor the confederation. From 1862 to 1890, he was prime minister, or

chancellor, of Prussia. Imitating Cavour, Bismarck planned and carried out the uni-

fication of Germany under the Hohenzollerns of Prussia, thereby excluding the

Habsburgs of Austria. He turned Prussia into a more modern, liberal state, albeit

with a weak constitution and parliament. His Realpolitik, though, preferred war-

fare, which he called decision by ‘‘blood and iron.’’ Bismarck knew he had to fight,

especially against Austria, to overcome the resistance of other great powers to Ger-

man unity. He therefore tricked his opponents into declaring wars and then

defeated them one after another with the most modern army in Europe.

Bismarck’s success remodeled Europe. In the Seven Weeks War (1866), the

efficient Prussian army with advanced planning and rapid-firing breech-loading

rifles quickly defeated Austria. Ousted from any part in a future united Germany, a

weakened Austrian imperial government granted political power to the Magyars or

Hungarians, transforming the state into the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary in

1867. Sadly for the Slavs and others, their nationalistic hopes under the Habsburg’s

German and Magyar rule remained unfulfilled.

Next, in 1870 the Spanish throne had become vacant, and princes from several

dynasties proposed to begin a new dynasty. One day, Chancellor Bismarck received

an insignificant report about his king, Wilhelm I, who was vacationing at the spa of

Ems. A petty French diplomat had bothered the king in the hope that no prince of

the Hohenzollern dynasty would compete for Spain. In a brilliant stroke of Realpoli-

tik, Bismarck reworded the ‘‘Ems Dispatch’’ to make it seem as if the French had

insulted the Prussian king. Napoleon III’s pride led him to declare war against Prus-

sia. In the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), Bismarck drew in the southern Ger-

man states, and the combined Prussian and German forces swiftly defeated France.

In the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles, the German princes acclaimed the Prussian

king as German Emperor Wilhelm I Hohenzollern. The Second German Empire

(1871–1918) quickly rose to be the most powerful country in Europe.

European nationalism, however, found difficulty including the Jews who had

lived in Germany, Italy, and many other older European countries for centuries.

Life had not always been easy, since many Christian rulers of the Middle Ages and

Renaissance practiced anti-Semitism, whether in the form of lack of civil rights,

prohibition from most jobs, confinement in ghettoes, expulsions from countries

such as England or Spain, and occasional pogroms (slaughtering of Jewish commu-

nities). Renaissance Venice invented the term ghetto for a neighborhood in which

Jews had to live. With the tolerant humanitarianism of the Enlightenment, Jews

actually gained civil rights. They could participate in politics and freely choose pro-

fessions. Once they were allowed entrance to universities, many Jews rose to pros-

perity and prominence in law, education, and medicine. Jews themselves had to

decide how much to assimilate, or act like their Western neighbors. Some asserted

strong cultural identity in language, clothing, and religious worship. Many, though,

ceased to keep a distinctly Jewish culture and became ‘‘secular.’’

Ironically, the Jews’ sudden success and prominence in the nineteenth century

only provoked more anti-Semitism. The most famous example of anti-Semitism

from that time was the Dreyfus Affair (1894–1906) in France. The French govern-

ment tried and convicted Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew, of treason in 1894 for

PAGE 285.................

17897$

CH12 10-12-10 08:32:30 PS