Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

been if the operations manager had not worked out what to do. Recovery procedures will

also shape customers’ perceptions of failure. Even where the customer sees a failure, it may

not necessarily lead to dissatisfaction. Indeed, in many situations, customers may well accept

that things do go wrong. If there is a metre of snow on the train lines, or if the restaurant

is particularly popular, we may accept that the product or service does not work. It is not

necessarily the failure itself that leads to dissatisfaction but often the organization’s response

to the breakdown. While mistakes may be inevitable, dissatisfied customers are not. A failure

may even be turned into a positive experience. A good recovery can turn angry, frustrated

customers into loyal ones. One research project used four service scenarios and examined the

willingness of customers to use an organization’s services again.

11

The four scenarios were:

1 The service is delivered to meet the customers’ expectations and there is full satisfaction.

2 There are faults in the service delivery but the customer does not complain about them.

3 There are faults in the service delivery and the customer complains but he/she has been

fobbed off or mollified. There is no real satisfaction with the service provider.

4 There are faults in the service delivery and the customer complains and feels fully satisfied

with the resulting action taken by the service providers.

Customers who are fully satisfied and do not experience any problems (1) are the most

loyal, followed by complaining customers whose complaints are resolved successfully (4).

Customers who experience problems but don’t complain (2) are in third place and last of all

come customers who do complain but are left with their problems unresolved and feelings

of dissatisfaction (3).

Recovery in high-visibility services

The idea of failure recovery has been developed particularly in service operations. As one

specialist put it, ‘If something goes wrong, as it often does, will anybody make special efforts to

get it right? Will somebody go out of his or her way to make amends to the customer? Does anyone

make an effort to offset the negative impact of a screw-up?’

12

It has also been suggested that service

recovery does not just mean ‘return to a normal state’ but to a state of enhanced perception.

All breakdowns require the deliverer to jump through a few hoops to get the customer back to

neutral. More hoops are required for victims to recover. Operations managers need to recognize

that all customers have recovery expectations that they want organizations to meet. Recovery

needs to be a planned process. Organizations therefore need to design appropriate responses

to failure, linked to the cost and the inconvenience caused by the failure to the customer,

which will meet the needs and expectations of the customer. Such recovery processes need to

be carried out either by empowered front-line staff or by trained personnel who are available

to deal with recovery in a way which does not interfere with day-to-day service activities.

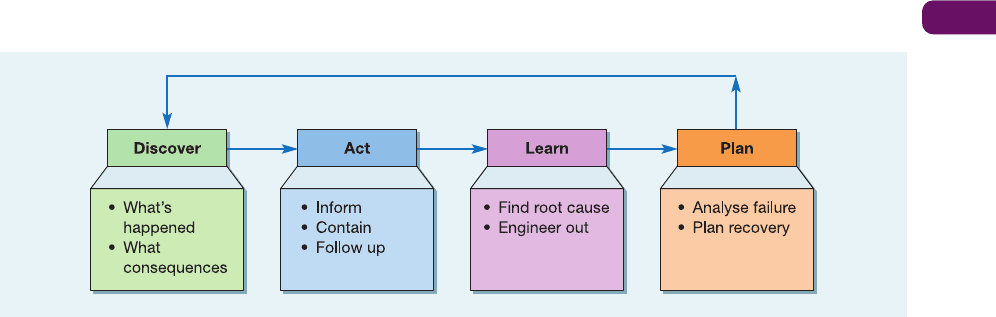

Failure planning

Identifying how organizations can recover from failure is of particular interest to service

operations because they can turn failures around to minimize the effect on customers or even

to turn failure into a positive experience. It is also of interest to other industries, however,

especially those where the consequences of failure are particularly severe. Bulk chemical

manufacturers and nuclear processors, for example, spend considerable resources in decid-

ing how they will cope with failures. The activity of devising the procedures which allow the

operation to recover from failure is called failure planning. It is often represented by stage

models, one of which is represented in Figure 19.11. We shall follow it through from the

point where failure is recognized.

Discover. The first thing any manager needs to do when faced with a failure is to discover its

exact nature. Three important pieces of information are needed: first of all, what exactly has

happened; second, who will be affected by the failure; and, third, why did the failure occur?

This last point is not intended to be a detailed inquest into the causes of failure (that comes

Failure planning

Part Four Improvement

594

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 594

Chapter 19 Risk management

595

Business continuity

later) but it is often necessary to know something of the causes of failure in case it is neces-

sary to determine what action to take.

Act. The discover stage could only take minutes or even seconds, depending on the severity

of the failure. If the failure is a severe one with important consequences, we need to move on

to doing something about it quickly. This means carrying out three actions, the first two of

which could be carried out in reverse order, depending on the urgency of the situation. First,

tell the significant people involved what you are proposing to do about the failure. In service

operations this is especially important where the customers need to be kept informed, both

for their peace of mind and to demonstrate that something is being done. In all operations,

however, it is important to communicate what action is going to happen so that everyone can

set their own recovery plans in motion. Second, the effects of the failure need to be contained

in order to stop the consequences spreading and causing further failures. The precise con-

tainment actions will depend on the nature of the failure. Third, there needs to be some kind

of follow-up to make sure that the containment actions really have contained the failure.

Learn. As discussed earlier in this chapter, the benefits of failure in providing learning oppor-

tunities should not be underestimated. In failure planning, learning involves revisiting the

failure to find out its root cause and then engineering out the causes of the failure so that it

will not happen again. This is the key stage for much failure planning.

Plan. Learning the lessons from a failure is not the end of the procedure. Operations

managers need formally to incorporate the lessons into their future reactions to failures. This

is often done by working through ‘in theory’ how they would react to failures in the future.

Specifically, this involves first identifying all the possible failures which might occur (in a

similar way to the FMEA approach). Second, it means formally defining the procedures

which the organization should follow in the case of each type of identified failure.

Business continuity

Many of the ideas behind failure, failure prevention and recovery are incorporated in the

growing field of business continuity. This aims to help operations avoid and recover from

disasters while keeping the business going, an issue that has risen to near the top of many

firms’ agenda since 11 September 2001. As operations become increasingly integrated (and

increasingly dependent on integrated technologies such as information technologies), critical

failures can result from a series of related and unrelated events and combine to disrupt totally

a company’s business. These events are the critical malfunctions which have the potential to

interrupt normal business activity and even stop the entire company, such as natural disasters,

fire, power or telecommunications failure, corporate crime, theft, fraud, sabotage, computer

system failure, bomb blast, scare or other security alert, key personnel leaving, becoming ill

or dying, key suppliers ceasing trading, contamination of product or processes, and so on.

Figure 19.11 The stages in failure planning

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 595

Summary answers to key questions

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment questions

and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an eBook – all at

www.myomlab.com.

➤ What is risk management?

■ Risk management is about things going wrong and what operations can do to stop things

going wrong. Or, more formally, ‘the process which aims to help organizations understand,

evaluate and take action on all their risks with a view to increasing the probability of their

success and reducing the likelihood of failure’.

■ It consists of four broad activities:

– Understanding what failures could occur.

– Preventing failures occurring.

– Minimizing the negative consequences of failure (called risk ‘mitigation’).

– Recovering from failures when they do occur.

➤ How can operations assess the potential causes of, and risks from failure?

■ There are several causes of operations failure including design failures, facilities failure, staff

failure, supplier failure, customer failure and environmental disruption.

■ There are three ways of measuring failure. ‘Failure rates’ indicate how often a failure is likely to

occur. ‘Reliability’ measures the chances of a failure occurring. ‘Availability’ is the amount of

available and useful operating time left after taking account of failures.

The procedures adopted by business continuity experts are very similar to those described in

this chapter:

● Identify and assess risks to determine how vulnerable the business is to various risks and to

take steps to minimize or eliminate them.

● Identify core business processes to prioritize those that are particularly important to the

business and which, if interrupted, would have to be brought back to full operation

quickly.

● Quantify recovery times to make sure staff understand priorities (for example, get customer

ordering system back into operation before the internal e-mail).

● Determine resources needed to make sure that resources will be available when required.

● Communicate to make sure that everyone in the operation knows what to do if disaster

strikes.

One response to the threat of such large-scale failures has been a rise in the number of

companies offering ‘replacement office’ operations. These are fully equipped offices, often

with access to a company’s current management information and with normal Internet and

telephone communications links. They are fully working offices but with no people. Should

a customer’s main operation be affected by a disaster, business can continue in the replace-

ment facility within days or even hours. The provision of this type of replacement office is,

in effect, a variation of the ‘redundancy’ approach to reducing the impact of failure that was

discussed earlier in this chapter.

Part Four Improvement

596

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 596

■ Failure over time is often represented as a failure curve. The most common form of this is the

so-called ‘bath-tub curve’ which shows the chances of failure being greater at the beginning

and end of the life of a system or part of a system.

■ Failure analysis mechanisms include accident investigation, product liability, complaint analysis,

critical incident analysis, and failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA).

➤ How can failures be prevented?

■ There are four major methods of improving reliability: designing out the fail points in the operation,

building redundancy into the operation, ‘fail-safeing’ some of the activities of the operation,

and maintenance of the physical facilities in the operation.

■ Maintenance is the most common way operations attempt to improve their reliability, with three

broad approaches. The first is running all facilities until they break down and then repairing

them, the second is regularly maintaining the facilities even if they have not broken down, and

the third is to monitor facilities closely to try to predict when breakdown might occur.

■ Two specific approaches to maintenance have been particularly influential: total productive

maintenance (TPM) and reliability-centred maintenance (RCM).

➤ How can operations mitigate the effects of failure?

■ Risk, or failure, mitigation means isolating a failure from its negative consequences.

■ Risk mitigation actions include:

– Mitigation planning.

– Economic mitigation.

– Containment (spatial and temporal).

– Loss reduction.

– Substitution.

➤ How can operations recover from the effects of failure?

■ Recovery can be enhanced by a systematic approach to discovering what has happened to

cause failure, acting to inform, contain and follow up the consequences of failure, learning to

find the root cause of the failure and preventing it taking place again, and planning to avoid the

failure occurring in the future.

■ The idea of ‘business continuity’ planning is a common form of recovery planning.

Chapter 19 Risk management

597

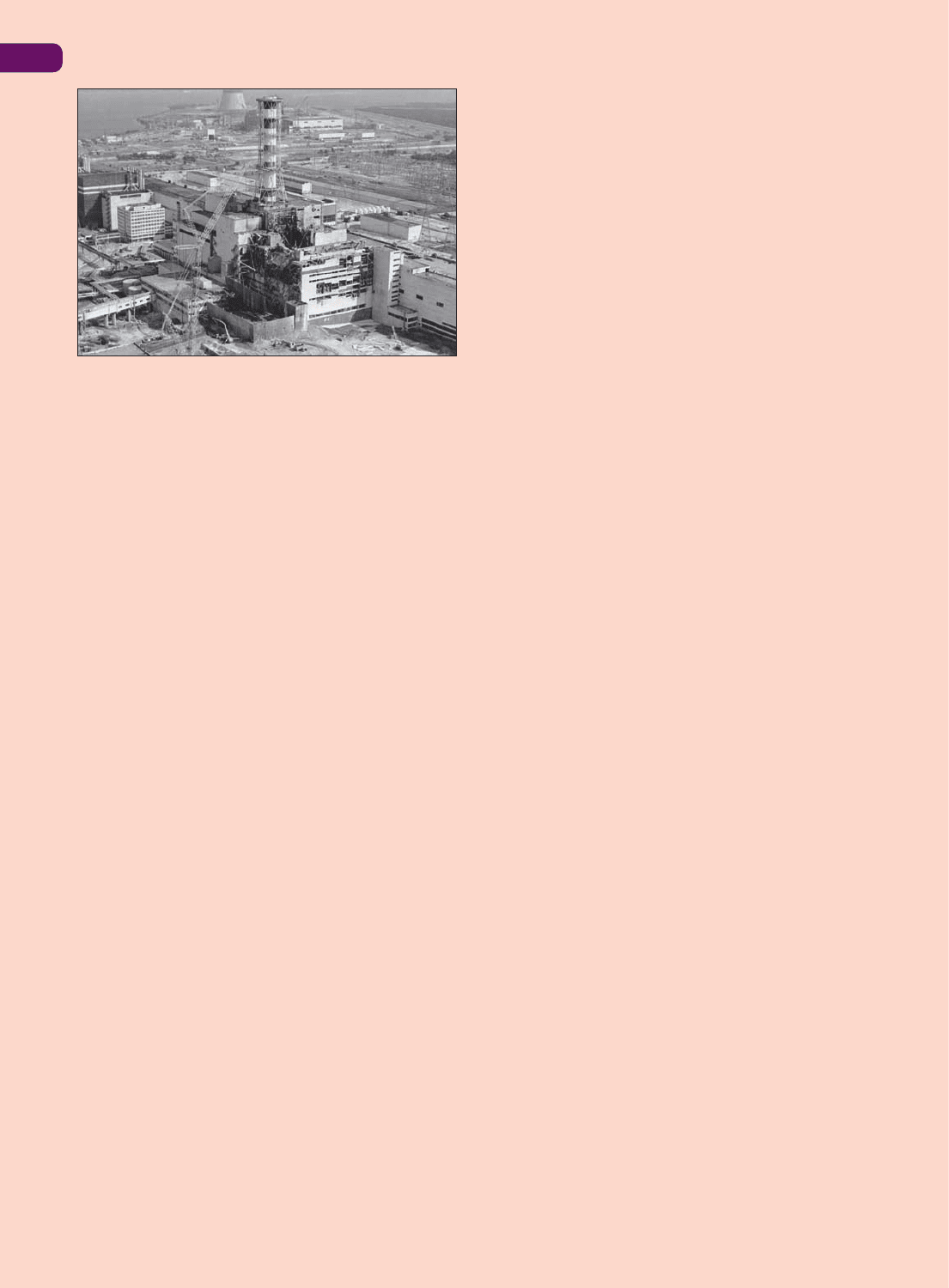

At 1.24 in the early hours of Saturday morning on 26 April

1986, the worst accident in the history of commercial nuclear

power generation occurred. Two explosions in quick

succession blew off the 1,000-tonne concrete sealing

cap of the Chernobyl-4 nuclear reactor. Molten core frag-

ments showered down on the immediate area and fission

Case study

The Chernobyl failure

13

products were released into the atmosphere. The accident

cost probably hundreds of lives and contaminated vast

areas of land in Ukraine.

Many reasons probably contributed to the disaster.

Certainly the design of the reactor was not new – around

30 years old at the time of the accident – and had been

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 597

conceived before the days of sophisticated computer-

controlled safety systems. Because of this, the reactor’s

emergency-handling procedures relied heavily on the skill

of the operators. This type of reactor also had a tendency

to run ‘out of control’ when operated at low power. For this

reason, the operating procedures for the reactor strictly pro-

hibited it being operated below 20 per cent of its maximum

power. It was mainly a combination of circumstance and

human error which caused the failure, however. Ironically,

the events which led up to the disaster were designed to

make the reactor safer. Tests, devised by a specialist team

of engineers, were being carried out to evaluate whether the

emergency core cooling system (ECCS) could be operated

during the ‘free-wheeling’ run-down of the turbine genera-

tor, should an off-site power failure occur. Although this

safety device had been tested before, it had not worked

satisfactorily and new tests of the modified device were to

be carried out with the reactor operating at reduced power

throughout the test period. The tests were scheduled for

the afternoon of Friday, 25 April 1986 and the plant power

reduction began at 1.00 pm. However, just after 2.00 pm,

when the reactor was operating at about half its full power,

the Kiev controller requested that the reactor should con-

tinue supplying the grid with electricity. In fact it was not

released from the grid until 11.10 that night. The reactor

was due to be shut down for its annual maintenance on

the following Tuesday and the Kiev controller’s request

had in effect shrunk the ‘window of opportunity’ available

for the tests.

The following is a chronological account of the hours up

to the disaster, together with an analysis by James Reason,

which was published in the Bulletin of the British Psycho-

logical Society the following year. Significant operator actions

are italicized. These are of two kinds: errors (indicated by

an ‘E’) and procedural violations (marked with a ‘V’).

25 April 1986

1.00 pm Power reduction started with the intention of

achieving 25 per cent power for test conditions.

2.00 pm ECCS disconnected from primary circuit. (This

was part of the test plan.)

2.05 pm Kiev controller asked the unit to continue supplying

grid. The ECCS was not reconnected (V). (This particular

violation is not thought to have contributed materially to the

disaster, but it is indicative of a lax attitude on the part of

the operators toward the observance of safety procedures.)

11.10 pm The unit was released from the grid and contin-

ued power reduction to achieve the 25 per cent power

level planned for the test programme.

26 April 1986

12.28 am Operator seriously undershot the intended power

setting (E). The power dipped to a dangerous one per cent.

(The operator had switched off the ‘auto-pilot’ and had

tried to achieve the desired level by manual control.)

1.00 am After a long struggle, the reactor power was

finally stabilized at 7 per cent – well below the intended

level and well into the low-power danger zone. At this point,

the experiment should have been abandoned, but it was

not (E). This was the most serious mistake (as opposed to

violation): it meant that all subsequent activity would be

conducted within the reactor’s zone of maximum instability.

This was apparently not appreciated by the operators.

1.03 am All eight pumps were started (V ). The safety reg-

ulations limited the maximum number of pumps in use at

any one time to six. This showed a profound misunder-

standing of the physics of the reactor. The consequence

was that the increased water flow (and reduced steam

fraction) absorbed more neutrons, causing more control

rods to be withdrawn to sustain even this low level of power.

1.19 am The feedwater flow was increased threefold (V ).

The operators appear to have been attempting to cope with

a falling steam-drum pressure and water level. The result

of their actions, however, was to further reduce the amount

of steam passing through the core, causing yet more con-

trol rods to be withdrawn. They also overrode the steam-

drum automatic shut-down (V). The effect of this was to

strip the reactor of one of its automatic safety systems.

1.22 am The shift supervisor requested printout to estab-

lish how many control rods were actually in the core. The

printout indicated only six to eight rods remaining. It was

strictly forbidden to operate the reactor with fewer than

twelve rods. Yet the shift supervisor decided to continue

with the tests (V). This was a fatal decision: the reactor was

thereafter without ‘brakes’.

1.23 am The steam line valves to No 8 turbine generator

were closed (V). The purpose of this was to establish the

conditions necessary for repeated testing, but its conse-

quence was to disconnect the automatic safety trips. This

was perhaps the most serious violation of all.

1.24 am An attempt was made to ‘scram’ the reactor by

driving in the emergency shut-off rods, but they jammed

within the now-warped tubes.

Part Four Improvement

598

Source: © Vladimir Repik/Reuters/Corbis

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 598

1.24 am Two explosions occurred in quick succession.

The reactor roof was blown off and 30 fires started in the

vicinity.

1.30 am Duty firemen were called out. Other units were

summoned from Pripyat and Chernobyl.

5.00 am Exterior fires had been extinguished, but the

graphite fire in the core continued for several days.

The subsequent investigation into the disaster highlighted

a number of significant points which contributed to it:

● The test programme was poorly worked out and the

section on safety measures was inadequate. Because

the ECCS was shut off during the test period, the safety

of the reactor was in effect substantially reduced.

● The test plan was put into effect before being approved

by the design group who were responsible for the

reactor.

● The operators and the technicians who were running

the experiment had different and non-overlapping skills.

● The operators, although highly skilled, had probably been

told that getting the test completed before the shut-down

would enhance their reputation. They were proud of their

ability to handle the reactor even in unusual conditions

and were aware of the rapidly reducing window of

opportunity within which they had to complete the test.

They had also probably ‘lost any feeling for the hazards

involved’ in operating the reactor.

● The technicians who had designed the test were elec-

trical engineers from Moscow. Their objective was to

solve a complex technical problem. In spite of having

designed the test procedures, they probably would not

know much about the operation of the nuclear power

station itself.

Again, in the words of James Reason: ‘Together, they

made a dangerous mixture: a group of single-minded but

non-nuclear engineers directing a team of dedicated but

over-confident operators. Each group probably assumed

that the other knew what it was doing. And both parties

had little or no understanding of the dangers they were

courting, or of the system they were abusing.’

Questions

1 What were the root causes which contributed to the

ultimate failure?

2 How could failure planning have helped prevent the

disaster?

Chapter 19 Risk management

599

These problems and applications will help to improve your analysis of operations. You

can find more practice problems as well as worked examples and guided solutions on

MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com.

‘We have a test bank where we test batches of 100 of our products continuously for 7 days and nights.

This week only 3 failed, the first after 10 hours, the second after 72 hours, and the third after 1,020 hours.’

What is the failure rate in percentage terms and in time terms for this product?

An automatic testing process takes samples of ore from mining companies and subjects them to four sequential

tests. The reliability of the four different test machines that perform the tasks is different. The first test machine

has a reliability of 0.99, the second has a reliability of 0.92, the third has a reliability of 0.98, and the fourth a

reliability of 0.95. If one of the machines stops working, the total process will stop. What is the reliability of the

total process?

For the product testing example in Problem 1, what is the mean time between failures (MTBF) for the products?

Conduct a survey amongst colleagues, friends and acquaintances of how they cope with the possibility that

their computers might ‘fail’, either in terms of ceasing to operate effectively, or in losing data. Discuss how the

concept of redundancy applies in such failure.

In terms of its effectiveness at managing the learning process, how does a university detect failures? What could

it do to improve its failure detection processes?

5

4

3

2

1

Problems and applications

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 599

Part Four Improvement

600

Dhillon, B.S. (2002) Engineering Maintenance: A Modern

Approach, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla. A comprehensive

book for the enthusiastic that stresses the ‘cradle-to-grave’

aspects of maintenance.

Li, Jun

||

Yu, Kui-Long

||

Wang, Liang-Xi

||

Song, Hai-Jun

Zhuangjiabing Gongcheng Xueyuan Xuebao (2007)

Research on operational risk management for equipment,

Journal of Academy of Armored Force Engineering, vol. 21,

no. 2, 8–11. Not as dull as it sounds. Deals with risks

in military operations including complex equipment

systems.

Regester, M. and Larkin, J. (2005) Risk Issues and Crisis Man-

agement: A Casebook of Best Practice, Kogan Page. Aimed at

practising managers with lots of advice. Good for getting

the flavour of how it is in practice.

Smith, D.J. (2000) Reliability, Maintainability and Risk,

Butterworth-Heinemann. A comprehensive and excellent

guide to all aspects of maintenance and reliability.

Selected further reading

www.smrp.org/ Site of the Society for Maintenance and Reliabil-

ity Professionals. Gives an insight into practical issues.

www.sre.org/ American Society of Reliability Engineers. The

newsletters give insights into reliability practice.

http://csob.berry.edu/faculty/jgrout/pokayoke.shtml The

poka-yoke page of John Grout. Some great examples,

tutorials, etc.

www.rspa.com/spi/SQA.html Lots of resources, involving

reliability and poka-yoke.

http://sra.org/ Site of the Society for Risk Analysis. Very wide

scope, but interesting.

www.hse.gov.uk/risk Health and Safety Executive of the UK

government.

www.theirm.org The home page of the Institute of Risk

Management.

www.opsman.org Lots of useful stuff.

Useful web sites

Now that you have finished reading this chapter, why not visit MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com where you’ll find more learning resources to help you

make the most of your studies and get a better grade?

M19_SLAC0460_06_SE_C19.QXD 10/20/09 9:55 Page 600

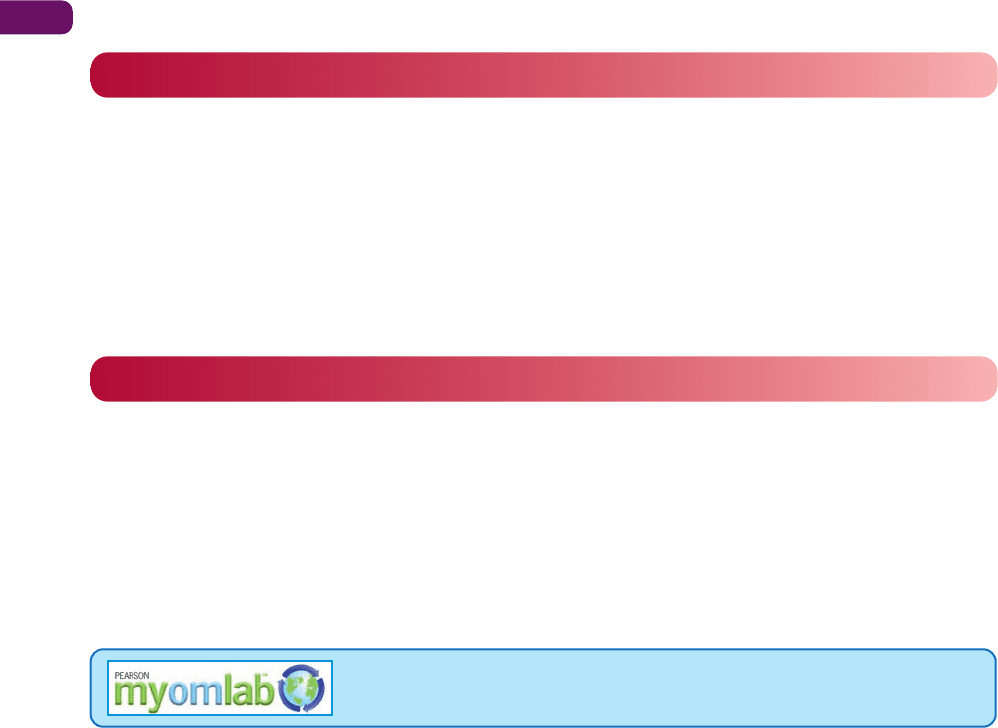

Introduction

This is the third, and final, chapter devoted to operations

improvement. It examines some of the managerial issues

associated with improvement can be organized. There are

no techniques as such in this chapter. Nor are all the issues

dealt with easily defined. Rather it covers the ‘soft’ side of

improvement. But do not dismiss this as in any way less

important. In practice it is often the ‘soft’ stuff that determines

the success or failure of improvement efforts. Moreover, the

‘soft’ stuff can be more difficult to get right than the ‘hard’, more

technique-based, aspects of improvement. The ‘hard’ stuff is

hard, but the ‘soft’ stuff is harder!

Chapter 20

Organizing for

improvement

Key questions

➤ Why does improvement need

organizing?

➤ How should the improvement effort

be linked to strategy?

➤ What information is needed for

improvement?

➤ What should be improvement

priorities?

➤ How can organizational culture

affect improvement?

➤ What are the key implementation

issues?

Figure 20.1 This chapter covers organizing of improvement

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment

questions and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an

eBook – all at www.myomlab.com.

M20_SLAC0460_06_SE_C20.QXD 10/20/09 9:56 Page 601

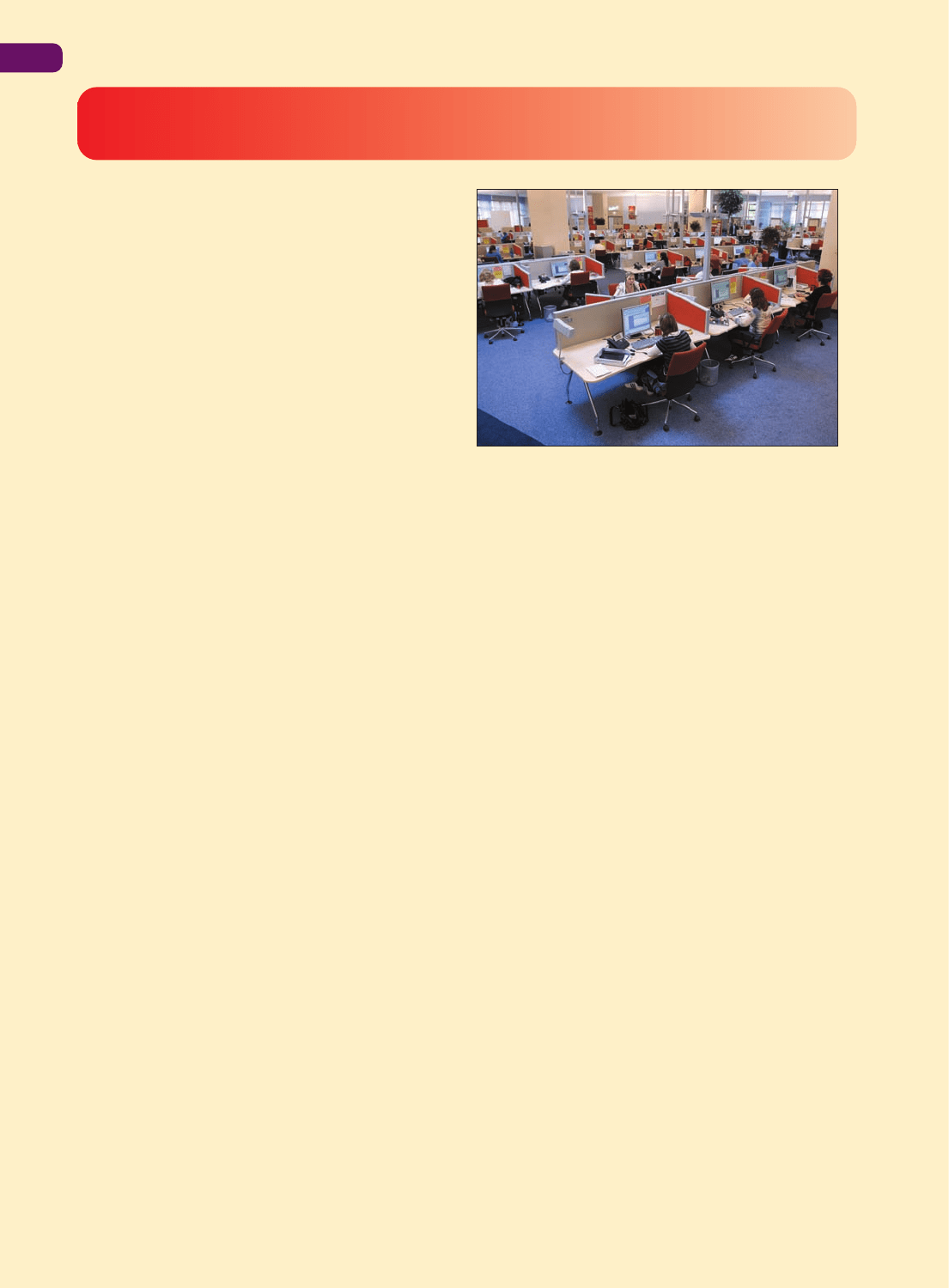

Operations effectiveness is just as important an issue

in public-sector operations as it is for commercial

companies. People have the right to expect that their

taxes are not wasted on inefficient or inappropriate public

processes. This is especially true of the tax collecting

system itself. It is never a popular organization in any

country, and taxpayers can be especially critical when

the tax collection process is not well managed. This was

very much on the minds of the Aarhus Region Customs

and Tax unit (Aarhus CT) when they developed their

award-winning quality initiative. The Aarhus Region is the

largest of Denmark’s twenty-nine local customs and tax

offices. It acts as an agent for central government in

collecting taxes in a professional and efficient manner

while being able to respond to taxpayers’ queries.

Aarhus CT must, ‘keep the user (customer) in focus’,

they say, ‘Users must pay what is due – no more, no

less and on time. But users are entitled to fair control

and collection, fast and efficient case work, service and

guidance, flexible employees, polite behaviour and a

professional telephone service.’ The Aarhus CT approach

to managing its quality initiative was built around a

number of key points.

● A recognition that poor-quality processes cause waste

both internally and externally.

● A determination to adopt a practice of regularly

surveying the satisfaction of its users. Employees were

also surveyed, both to understand their views on

quality and to check that their working environment

would help to instil the principles of high-quality

service.

● Although a not-for-profit organization, quality

measures included measuring the organization’s

adherence to financial targets as well as error

reporting.

● Internal processes were redefined and redesigned

to emphasize customer needs and internal staff

requirements. For example, Aarhus CT was the only

tax region in Denmark to develop an independent

information process that was used to analyse

customers’ needs and ‘prevent misunderstanding in

users’ perception of legislation’.

● Internal processes were designed to allow staff the

time and opportunity to develop their own skills,

exchange ideas with colleagues and take on greater

responsibility for management of their own work

processes.

● The organization set up what it called its ‘Quality

Organization’ (QO) structure which spanned all

divisions and processes. The idea of the QO was to

foster staff commitment to continuous improvement

and to encourage the development of ideas for

improving process performance. Within the QO

was the Quality Group (QG). This consisted of four

managers and four process staff, and reported

directly to senior management. It also set up a

number of improvement groups and suggestion

groups consisting of managers as well as process

staff. The role of the suggestion groups was to

collect and process ideas for improvement which

the improvement groups would then analyse and if

appropriate implement.

● Aarhus CT was keen to stress that their Quality

Groups would eventually become redundant if they

were to be successful. In the short term they would

maintain a stream of improvement ideas, but in the

long term they should have fully integrated the idea

of quality improvement into the day-to-day activities

of all staff.

Operations in practice Taxing quality

1

Part Four Improvement

602

Source: Rex Features

M20_SLAC0460_06_SE_C20.QXD 10/20/09 9:56 Page 602

Chapter 20 Organizing for improvement

603

Why the improvement effort needs organizing

Improvement does not just happen. It needs organizing and it needs implementing. It

also needs a purpose that is well thought through and clearly articulated. Although much

operations improvement will take place at an operational level, and especially if one is

following a continuous improvement philosophy (see previous chapter), it will be small-scale

and incremental. Nevertheless, it must be placed in some kind of context. That is, it should

be clear why improvement is happening as well as what it consists of. This means linking the

improvement to the overall strategic objectives of the organization. This is why we start this

chapter by thinking about improvement in a strategic context. Improvement must also be

based on sound information. If the performance of operations and the processes within them

are to be improved, one must first be able to define and measure exactly what we mean by

‘performance’. Furthermore, benchmarking one’s own activities and performance against

other organizations’ activities and performance can lead to valuable insights and help to

quantify progress. It also helps to answer some basic improvement questions such as

who should be in charge of it, when should it take place, and how one should go about

ensuring that improvement really does impact the performance of the organization. This is

why in this chapter we will deal with such issues as measuring performance, benchmarking,

prioritization, learning and culture, and the role of systems of procedures in the imple-

mentation process.

Remember also that the issue of how improvement should be organized is not a new con-

cern. It has been a concern of management writers for decades. For example, W.E. Deming

(considered in Japan to be the father of quality control) asserted that quality starts with top

management and is a strategic activity.

2

It is claimed that much of the success in terms of

quality in Japanese industry was the result of his lectures to Japanese companies in the 1950s.

3

Deming’s basic philosophy is that quality and productivity increase as ‘process variability’

(the unpredictability of the process) decreases. In his 14 points for quality improvement, he

emphasizes the need for statistical control methods, participation, education, openness and

purposeful improvement:

1 Create constancy of purpose.

2 Adopt new philosophy.

3 Cease dependence on inspection.

4 End awarding business on price.

5 Improve constantly the system of production and service.

6 Institute training on the job.

7 Institute leadership.

8 Drive out fear.

9 Break down barriers between departments.

10 Eliminate slogans and exhortations.

11 Eliminate quotas or work standards.

12 Give people pride in their job.

13 Institute education and a self-improvement programme.

14 Put everyone to work to accomplish it.

Linking improvement to strategy

At one level, the objective of any improvement is obvious – it tries to make things better!

But, does this mean better in every way or better in some specific manner? And how much

better does better mean? This is why we need some more general framework to put any

M20_SLAC0460_06_SE_C20.QXD 10/20/09 9:56 Page 603