Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Part Three Planning and control

394

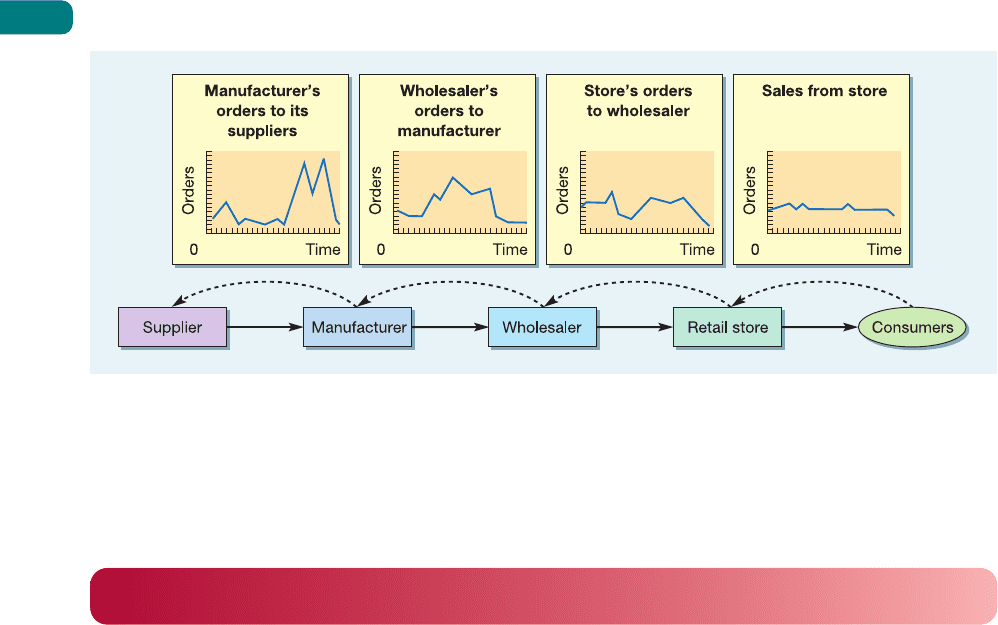

Figure 13.8 Typical supply chain dynamics

child says out loud what the message is, and the children are amused by the distortion of the

original message. Figure 13.8 shows the bullwhip effect in a typical supply chain, with relatively

small fluctuations in the market cause increasing volatility further back in the chain.

Supply chain improvement

Increasingly important in supply chain practice are attempts to improve supply chain per-

formance. These are usually attempts to understand the complexity of supply chain processes;

others focus on coordinating activities throughout the chain.

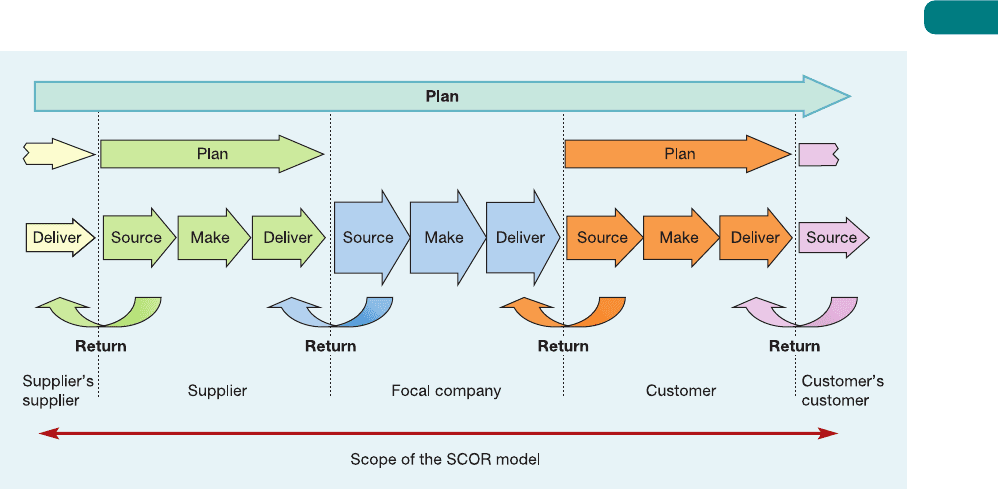

The SCOR model

The Supply Chain Operations Reference model (SCOR) is a broad, but highly structured and

systematic, framework to supply chain improvement that has been developed by the Supply

Chain Council (SCC), a global non-profit consortium. The framework uses a methodology,

diagnostic and benchmarking tools that are increasingly widely accepted for evaluating and

comparing supply chain activities and their performance. Just as important, the SCOR model

allows its users to improve, and communicate supply chain management practices within

and between all interested parties in their supply chain by using a standard language and

a set of structured definitions. The SCC also provides a benchmarking database by which

companies can compare their supply chain performance to others in their industries and

training classes. Companies that have used the model include BP, AstraZeneca, Shell, SAP

AG, Siemens AG and Bayer. The model uses three well-known individual techniques turned

into an integrated approach. These are:

● Business process modelling

● Benchmarking performance

● Best practice analysis.

Business process modelling

SCOR does not represent organizations or functions, but rather processes. Each basic ‘link’

in the supply chain is made up of five types of process, each process being a ‘supplier–

customer’ relationship, see Figure 13.9.

● ‘Source’ is the procurement, delivery, receipt and transfer of raw material items, sub-

assemblies, products and/or services.

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 394

● ‘Make’ is the transformation process of adding value to products and services through

mixing production operations processes.

● ‘Deliver’ processes perform all customer-facing order management and fulfilment activities

including outbound logistics.

● ‘Plan’ processes manage each of these customer–supplier links and balance the activity of

the supply chain. They are the supply and demand reconciliation process, which includes

prioritization when needed.

● ‘Return’ processes look after the reverse logistics flow of moving material back from

end-customers upstream in the supply chain because of product defects or post-delivery

customer support.

All these processes are modelled at increasingly detailed levels from level 1 through to more

detailed process modelling at level 3.

Benchmarking performance

Performance metrics in the SCOR model are also structured by level, as is process analysis.

Level 1 metrics are the yardsticks by which an organization can measure how successful it

is in achieving its desired positioning within the competitive environment, as measured by

the performance of a particular supply chain. These level 1 metrics are the key performance

indicators (KPIs) of the chain and are created from lower-level diagnostic metrics (called

level 2 and level 3 metrics) which are calculated on the performance of lower-level processes.

Some metrics do not ‘roll up’ to level 1, these are intended to diagnose variations in perform-

ance against plan.

Best practice analysis

Best practice analysis follows the benchmarking activity that should have measured the

performance of the supply chain processes and identified the main performance gaps. Best

practice analysis identifies the activities that need to be performed to close the gaps. SCC

members have identified more than 400 ‘best practices’ derived from their experience. The

definition of a ‘best practice’ in the SCOR model is one that:

● Is current – neither untested (emerging) nor outdated.

● Is structured – it has clearly defined goals, scope and processes.

Chapter 13 Supply chain planning and control

395

Figure 13.9 Matching the operations resources in the supply chain with market requirements

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 395

● Is proven – there has been some clearly demonstrated success.

● Is repeatable – it has been demonstrated to be effective in various contexts.

● Has an unambiguous method – the practice can be connected to business processes,

operations strategy, technology, supply relationships, and information or knowledge man-

agement systems.

● Has a positive impact on results – operations improvement can be linked to KPIs.

The SCOR roadmap

The SCOR model can be implemented by using a five-phase project ‘roadmap’. Within this

roadmap lies a collection of tools and techniques that both help to implement and support

the SCOR framework. In fact many of these tools are commonly used management decision

tools such as Pareto charts, cause–effect diagrams, maps of material flow and brainstorming.

Phase 1: Discover – Involves supply-chain definition and prioritization where a ‘Project

Charter’ sets the scope for the project. This identifies logic groupings of supply chains within

the scope of the project. The priorities, based on a weighted rating method, determine which

supply chains should be dealt with first. This phase also identifies the resources that are

required, identified and secured through business process owners or actors.

Phase 2: Analyse – Using data from benchmarking and competitive analysis, the appropriate

level of performance metrics are identified; that will define the strategic requirements of each

supply chain.

Phase 3: Material flow design – In this phase the project teams have their first go at creating a

common understanding of how processes can be developed. The current state of processes is

identified and an initial analysis attempts to see where there are opportunities for improvement.

Phase 4: Work and information flow design – The project teams collect and analyse the work

involved in all relevant processes (plan, source, make, deliver and return) and map the pro-

ductivity and yield of all transactions.

Phase 5: Implementation planning – This is the final and preparation phase for communicat-

ing the findings of the project. Its purpose is to transfer the knowledge of the SCOR team(s)

to individual implementation or deployment teams.

Benefits of the SCOR model

Claimed benefits from using the SCOR model include improved process understanding

and performance, improved supply chain performance, increased customer satisfaction and

retention, a decrease in required capital, better profitability and return on investment, and

increased productivity. And, although most of these results could arguably be expected when

any company starts focusing on business processes improvements, SCOR proponents argue

that using the model gives an above average and supply focused improvement.

Part Three Planning and control

396

Although the SCOR model is increasingly being adopted, it has been criticized for under-

emphasizing people issues. The SCOR model assumes, but does not explicitly address, the

human resource base skill set, notwithstanding the model’s heavy reliance on supply chain

knowledge to understand the model and methodology properly. Often external expertise

is needed to support the process. This, along with the nature of the SCC membership,

also implies that the SCOR model may be appropriate only for relatively large companies

that are more likely to have the necessary business capabilities to implement the model.

Many small to medium-sized companies may find difficulty in handle full-scale model

implementation. Some critics would also argue that the model lacks a link to the financial

plans of a company, making it very difficult to highlight the benefits obtainable, as well as

inhibiting senior management support.

Critical commentary

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 396

The effects of e-business on supply chain management

practice

13

New information technology applications combined with internet-based e-business have

transformed supply chain management practice. Largely, this is because they provide better

and faster information to all stages in the supply chain. Information is the lifeblood of

supply chain management. Without appropriate information, supply chain managers cannot

make the decisions that coordinate activities and flows through the chain. Without appro-

priate information, each stage in the supply chain has relatively few cues to tell them what

is happening elsewhere in the chain. To some extent, they are ‘driving blind’ and having to

rely on the most obvious of mismatches between the activities of different stages in the chain

(such as excess inventory) to inform their decisions. Conversely, with accurate and ‘near

real-time’ information, the disparate elements in supply chains can integrate their efforts

to the benefit of the whole chain and, eventually, the end-customer. Just as importantly, the

collection, analysis and distribution of information using e-business technologies is far less

expensive to arrange than previous, less automated methods. Table 13.5 summarizes some of

the effects of e-business on three important aspects of supply chain management – business

and market information flow, product and service flow, and the cash flow that comes as a

result of product and service flow.

Information-sharing

One of the reasons for the fluctuations in output described in the example earlier was that

each operation in the chain reacted to the orders placed by its immediate customer. None of

the operations had an overview of what was happening throughout the chain. If information

had been available and shared throughout the chain, it is unlikely that such wild fluctuations

would have occurred. It is sensible therefore to try to transmit information throughout the

chain so that all the operations can monitor true demand, free of these distortions. An obvious

improvement is to make information on end-customer demand available to upstream

operations. Electronic point-of-sale (EPOS) systems used by many retailers attempt to do this.

Sales data from checkouts or cash registers are consolidated and transmitted to the warehouses,

transportation companies and supplier manufacturing operations that form their supply

chain. Similarly, electronic data interchange (EDI) helps to share information (see the short

case on Seven-Eleven Japan). EDI can also affect the economic order quantities shipped

between operations in the supply chain.

Information sharing helps

improve supply chain

performance

Chapter 13 Supply chain planning and control

397

Table 13.5 Some effects of e-business on supply chain management practice

Supply-chain-

related activities

Beneficial

effects of

e-business

practices

Cash flow

Supplier payments

Customer invoicing

Customer receipts

Faster movement of cash

Automated cash

movement

Integration of financial

information with sales

and operations activities

Product/service flow

Purchasing

Inventory management

Throughput / waiting

times

Distribution

Lower purchasing

administration costs

Better purchasing deals

Reduced bullwhip effect

Reduced inventory

More efficient

distribution

Market/sales

information flow

Understanding

customers’ needs

Designing appropriate

products / services

Demand forecasting

Better customer

relationship management

Monitoring real-time

demand

On-line customization

Ability to coordinate

output with demand

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 397

Channel alignment

Channel alignment means the adjustment of scheduling, material movements, stock levels,

pricing and other sales strategies so as to bring all the operations in the chain into line with

each other. This goes beyond the provision of information. It means that the systems and

methods of planning and control decision-making are harmonized through the chain. For

example, even when using the same information, differences in forecasting methods or

purchasing practices can lead to fluctuations in orders between operations in the chain.

One way of avoiding this is to allow an upstream supplier to manage the inventories of its

downstream customer. This is known as vendor-managed inventory (VMI). So, for example,

a packaging supplier could take responsibility for the stocks of packaging materials held by

a food manufacturing customer. In turn, the food manufacturer takes responsibility for the

stocks of its products which are held in its customer’s, the supermarket’s warehouses.

Part Three Planning and control

398

Seven-Eleven Japan (SEJ) is that country’s largest and

most successful retailer. The average amount of stock in

an SEJ store is between 7 and 8.4 days of demand, a

remarkably fast stock turnover for any retailer. Industry

analysts see SEJ’s agile supply chain management as

being the driving force behind its success. It is an agility

that is supported by a fully integrated information system

that provides visibility of the whole supply chain and

ensures fast replenishment of goods in its stores

customized exactly to the needs of individual stores.

As a customer comes to the checkout counter the

assistant first keys in the customer’s gender and

approximate age and then scans the bar codes of the

purchased goods. This sales data is transmitted to the

Seven-Eleven headquarters through its own high-speed

lines. Simultaneously, the store’s own computer system

records and analyzes the information so that store

managers and headquarters have immediate point-of-sale

information. This allows both store managers and

headquarters to, hour by hour, analyze sales trends, any

stock-outs, types of customer buying certain products,

and so on. The headquarters computer aggregates all this

data by region, product and time so that all parts of the

supply chain, from suppliers through to the stores, have

the information by the next morning. Every Monday,

the company chairman and top executives review all

performance information for the previous week and

develop plans for the up-coming week. These plans are

presented on Tuesday morning to SEJ’s ‘operations field

counsellors’ each of which is responsible for facilitating

performance improvement in around eight stores. On

Tuesday afternoon the field counsellors for each region

meet to decide how they will implement the overall plans

Short case

Seven-Eleven Japan’s agile

supply chain

14

for their region. On Tuesday night the counsellors fly

back to their regions and by next morning are visiting

their stores to deliver the messages developed at

headquarters which will help the stores implement their

plans. SEJ’s physical distribution is also organized on an

agile basis. The distribution company maintains radio

communications with all drivers and SEJ’s headquarters

keeps track of all delivery activities. Delivery times and

routes are planned in great detail and published in the

form of a delivery time-table. On average each delivery

takes only one and half minutes at each store, and drivers

are expected to make their deliveries within ten minutes

of scheduled time. If a delivery is late by more than thirty

minutes the distribution company has to pay the store a

fine equivalent to the gross profit on the goods being

delivered. The agility of the whole supply system also

allows SEJ headquarters and the distribution company to

respond to disruptions. For example, on the day of the

Kobe earthquake, SEJ used 7 helicopters and 125 motor

cycles to rush through a delivery of 64,000 rice balls to

earthquake victims.

Channel alignment helps

improve supply chain

performance

Vendor-managed

inventory

Source: Getty Images

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 398

Operational efficiency

‘Operational efficiency’ means the efforts that each operation in the chain can make to

reduce its own complexity, reduce the cost of doing business with other operations in the

chain and increase throughput time. The cumulative effect of these individual activities

is to simplify throughput in the whole chain. For example, imagine a chain of operations

whose performance level is relatively poor: quality defects are frequent, the lead time to

order products and services is long, and delivery is unreliable and so on. The behaviour of

the chain would be a continual sequence of errors and effort wasted in replanning to com-

pensate for the errors. Poor quality would mean extra and unplanned orders being placed,

and unreliable delivery and slow delivery lead times would mean high safety stocks. Just as

important, most operations managers’ time would be spent coping with the inefficiency. By

contrast, a chain whose operations had high levels of operations performance would be

more predictable and have faster throughput, both of which would help to minimize supply

chain fluctuations.

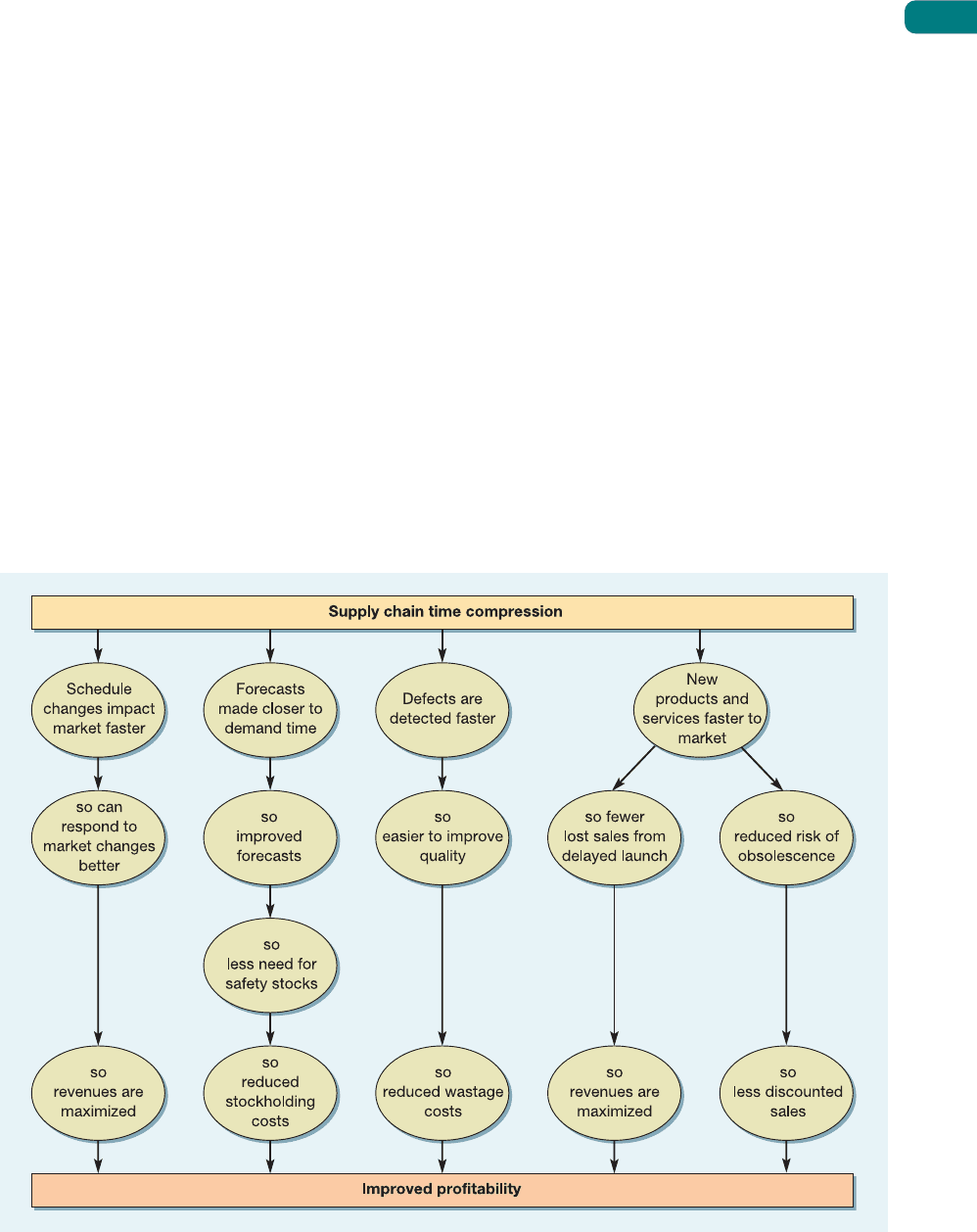

One of the most important approaches to improving the operational efficiency of supply

chains is known as time compression. This means speeding up the flow of materials down

the chain and the flow of information back up the chain. The supply chain dynamics effect

we observed in Table 13.4 was due partly to the slowness of information moving back up the

chain. Figure 13.10 illustrates the advantages of supply chain time compression in terms of

its overall impact on profitability.

15

Chapter 13 Supply chain planning and control

399

Figure 13.10 Supply chain time compression can both reduce costs and increase revenues

Source: Based on Towill

Operational efficiency

helps improve supply

chain performance

Supply chain time

compression

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 399

Supply chain vulnerability

One of the consequences of the agile supply chain concept has been to take more seriously the

possibility of supply chain risk and disruption. The concept of agility includes consideration

of how supply chains have to cope with common disruptions such as late deliveries, quality

problems, incorrect information, and so on. Yet far more dramatic events can disrupt supply

chains. Global sourcing means that parts are shipped around the world on their journey

through the supply chain. Microchips manufactured in Taiwan could be assembled to printed

circuit boards in Shanghai which are then finally assembled into a computer in Ireland.

Perhaps most significantly, there tends to be far less inventory in supply chains that could

buffer interruptions to supply. According to Professor Martin Christopher, an authority on

supply chain management, ‘Potentially the risk of disruption has increased dramatically as the

result of a too-narrow focus on supply chain efficiency at the expense of effectiveness. Unless man-

agement recognizes the challenge and acts upon it, the implications for us all could be chilling.’

16

These ‘chilling’ effects can arise as a result of disruptions such as natural disasters, terrorist

incidents, industrial or direct action such as strikes and protests, accidents such as fire in a vital

component supplier’s plant, and so on. Of course, many of these disruptions have always been

present in business. It is the increased vulnerability of supply chains that has made many

companies place more emphasis on understanding supply chain risks.

Part Three Planning and control

400

Summary answers to key questions

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment questions

and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an eBook – all at

www.myomlab.com.

➤ What are supply chain management and its related activities?

■ Supply chain management is a broad concept which includes the management of the entire

supply chain from the supplier of raw material to the end-customer.

■ Its component activities include purchasing, physical distribution management, logistics,

materials management and customer relationship management (CRM).

➤ What are the types of relationship between operations in supply chains?

■ Supply networks are made up of individual pairs of buyer–supplier relationships. The use of

Internet technology in these relationships has led to a categorization based on a distinction

between business and consumer partners. Business-to-business (B2B) relationships are of the

most interest in operations management terms. They can be characterized on two dimensions

– what is outsourced to a supplier, and the number and closeness of the relationships.

■ Traditional market supplier relationships are where a purchaser chooses suppliers on an

individual periodic basis. No long-term relationship is usually implied by such ‘transactional’

relationships, but it makes it difficult to build internal capabilities.

■ Virtual operations are an extreme form of outsourcing where an operation does relatively little

itself and subcontracts almost all its activities.

■ Partnership supplier relationships involve customers forming long-term relationships with

suppliers. In return for the stability of demand, suppliers are expected to commit to high levels

of service. True partnerships are difficult to sustain and rely heavily on the degree of trust which

is allowed to build up between partners.

Supply chain risk

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 400

Chapter 13 Supply chain planning and control

401

Garment retailing has changed. No longer is there a standard

look that all retailers adhere to for a whole season. Fashion

is fast, complex and furious. Different trends overlap and

fashion ideas that are not even on a store’s radar screen

can become ‘must haves’ within six months. Many retail

businesses with their own brands, such as H&M and Zara,

sell up-to-the-minute fashionability at low prices, in stores

that are clearly focused on one particular market. In the

Case study

Supplying fast fashion

17

world of fast fashion catwalk designs speed their way into

high-street stores at prices anyone can afford. The quality

of the garment means that it may only last one season, but

fast-fashion customers don’t want yesterday’s trends. As

Newsweek puts it, ‘being a “quicker picker-upper” is what

made fashion retailers H&M and Zara successful. [They]

thrive by practicing the new science of “fast fashion”; com-

pressing product development cycles as much as six times.’

■ Customer relationship management (CRM) is a method of learning more about customers’

needs and behaviours in order to develop stronger relationships with them. It brings together all

information about customers to gain insight into their behaviour and their value to the business.

➤ What is the ‘natural’ pattern of behaviour in supply chains?

■ Marshall Fisher distinguishes between functional markets and innovative markets. He argues

that functional markets, which are relatively predictable, require efficient supply chains, whereas

innovative markets, which are less predictable, require ‘responsive’ supply chains.

■ Supply chains exhibit a dynamic behaviour known as the ‘bullwhip’ effect. This shows how

small changes at the demand end of a supply chain are progressively amplified for operations

further back in the chain.

➤ How can supply chains be improved?

■ The Supply Chain Operations Reference model (SCOR) is a highly structured framework for

supply chain improvement that has been developed by the Supply Chain Council (SCC).

■ The model uses three well-known individual techniques turned into an integrated approach.

These are:

– Business process modelling

– Benchmarking performance

– Best practice analysis.

■ To reduce the ‘bullwhip’ effect, operations can adopt some mixture of three coordination

strategies:

– information-sharing: the efficient distribution of information throughout the chain can reduce

demand fluctuations along the chain by linking all operations to the source of demand;

– channel alignment: this means adopting the same or similar decision-making processes

throughout the chain to coordinate how and when decisions are made;

– operational efficiency: this means eliminating sources of inefficiency or ineffectiveness in

the chain; of particular importance is ‘time compression’, which attempts to increase the

throughput speed of the operations in the chain.

■ Increasingly, supply risks are being managed as a countermeasure to their vulnerability.

➔

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 401

But the retail operations that customers see are only the

end part of the supply chain that feeds them. And these

have also changed.

At its simplest level, the fast-fashion supply chain has

four stages. First, the garments are designed, after which

they are manufactured; they are then distributed to the retail

outlets where they are displayed and sold in retail opera-

tions designed to reflect the businesses’ brand values. In

this short case we examine two fast-fashion operations,

Hennes and Mauritz (known as H&M) and Zara, together

with United Colors of Benetton (UCB), a similar chain, but

with a different market positioning.

Benetton – almost fifty years ago Luciano Benetton took

the world of fashion by storm by selling the bright, casual

sweaters designed by his sister across Europe (and later the

rest of the world), promoted by controversial advertising.

By 2005 the Benetton Group was present in 120 countries

throughout the world. Selling casual garments, mainly under

its United Colors of Benetton (UCB) and its more fashion-

oriented Sisley brands, it produces 110 million garments a

year, over 90 per cent of them in Europe. Its retail network

of over 5,000 stores produces revenue of around A2 billion.

Benetton products are seen as less ‘high fashion’ but

higher quality and durability, with higher prices, than H&M

and Zara.

H&M – established in Sweden in 1947, now sells clothes

and cosmetics in over 1,000 stores in 20 countries around

the world. The business concept is ‘fashion and quality

at the best price’. With more than 40,000 employees, and

revenues of around SEK 60,000 million, its biggest market

is Germany, followed by Sweden and the UK. H&M are

seen by many as the originator of the fast fashion concept.

Certainly they have years of experience at driving down

the price of up-to-the-minute fashions. ‘We ensure the

best price,’ they say, ‘by having few middlemen, buying

large volumes, having extensive experience of the clothing

industry, having a great knowledge of which goods should

be bought from which markets, having efficient distribution

systems, and being cost-conscious at every stage’.

Zara – the first store opened almost by accident in 1975

when Amancio Ortega Gaona, a women’s pyjama manu-

facturer, was left with a large cancelled order. The shop he

opened was intended only as an outlet for cancelled orders.

Now, Inditex, the holding group that includes the Zara brand,

has over 1,300 stores in 39 countries with sales of over

A3 billion. The Zara brand accounts for over 75 per cent of

the group’s total retail sales, and is still based in northwest

Spain. By 2003 it had become the world’s fastest-growing

volume garment retailer. The Inditex group also has several

other branded chains including Pull and Bear, and Massimo

Dutti. In total it employs almost 40,000 people in a busi-

ness that is known for a high degree of vertical integration

compared with most fast-fashion companies. The company

believes that it is their integration along the supply chain

that allows them to respond to customer demand fast and

flexibly while keeping stock to a minimum.

Design

All three businesses emphasize the importance of design

in this market. Although not haute couture, capturing design

trends is vital to success. Even the boundary between high

and fast fashion is starting to blur. In 2004 H&M recruited

high-fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld, previously noted for

his work with more exclusive brands. For H&M his designs

were priced for value rather than exclusivity, ‘Why do I work

for H&M? Because I believe in inexpensive clothes, not

“cheap” clothes’, said Lagerfeld. Yet most of H&M’s pro-

ducts come from over a hundred designers in Stockholm

who work with a team of 50 pattern designers, around

100 buyers and a number of budget controllers. The

department’s task is to find the optimum balance between

the three components making up H&M’s business concept

– fashion, price and quality. Buying volumes and delivery

dates are then decided.

Zara’s design functions are organized in a different way

from most similar companies’. Conventionally, the design

input comes from three separate functions: the designers

themselves, market specialists, and buyers who place orders

on to suppliers. At Zara the design stage is split into three

product areas: women’s, men’s and children’s garments.

Part Three Planning and control

402

Source: Press Association Images

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 402

In each area, designers, market specialists and buyers are

co-located in design halls that also contain small workshops

for trying out prototype designs. The market specialists

in all three design halls are in regular contact with Zara

retail stores, discussing customer reaction to new designs.

In this way, the retail stores are not the end of the whole

supply chain but the beginning of the design stage of the

chain. Zara’s around 300 designers, whose average age is

26, produce approximately 40,000 items per year of which

about 10,000 go into production.

Benetton also has around 300 designers, who not only

design for all their brands, but also are engaged in research-

ing new materials and clothing concepts. Since 2000 the

company has moved to standardize their range globally.

At one time more than 20 per cent of its ranges were

customized to the specific needs of each country, now only

between 5 and 10 per cent of garments are customized.

This reduced the number of individual designs offered glob-

ally by over 30 per cent, strengthening the global brand

image and reducing production costs.

Both H&M and Zara have moved away from the tradi-

tional industry practice of offering two ‘collections’ a year,

for Spring/Summer and Autumn/Winter. Their ‘seasonless

cycle’ involves the continual introduction of new products

on a rolling basis throughout the year. This allows designers

to learn from customers’ reactions to their new products

and incorporate them quickly into more new products. The

most extreme version of this idea is practised by Zara.

A garment will be designed and a batch manufactured

and ‘pulsed’ through the supply chain. Often the design

is never repeated; it may be modified and another batch

produced, but there are no ‘continuing’ designs as such.

Even Benetton have increased the proportion of what they

call ‘flash’ collections, small collections that are put into its

stores during the season.

Manufacturing

At one time Benetton focused its production on its Italian

plants. Then it significantly increased its production outside

Italy to take advantage of lower labour costs. Non-Italian

operations include factories in North Africa, Eastern Europe

and Asia. Yet each location operates in a very similar manner.

A central, Benetton-owned, operation performs some manu-

facturing operations (especially those requiring expensive

technology) and coordinates the more labour-intensive pro-

duction activities that are performed by a network of smaller

contractors (often owned and managed by ex-Benetton

employees). These contractors may in turn subcontract

some of their activities. The company’s central facility in

Italy allocates production to each of the non-Italian networks,

deciding what and how much each is to produce. There

is some specialization, for example, jackets are made in

Eastern Europe while T-shirts are made in Spain. Benetton

also has a controlling share in its main supplier of raw

materials, to ensure fast supply to its factories. Benetton

are also known for the practice of dyeing garments after

assembly rather than using dyed thread or fabric. This

postpones decisions about colours until late in the supply

process so that there is a greater chance of producing what

is needed by the market.

H&M does not have any factories of its own, but instead

works with around 750 suppliers. Around half of produc-

tion takes place in Europe and the rest mainly in Asia. It

has 21 production offices around the world that between

them are responsible for coordinating the suppliers who

produce over half a billion items a year for H&M. The rela-

tionship between production offices and suppliers is vital,

because it allows fabrics to be bought in early. The actual

dyeing and cutting of the garments can then be decided at

a later stage in the production The later an order can be

placed on suppliers, the less the risk of buying the wrong

thing. Average supply lead times vary from three weeks

up to six months, depending on the nature of the goods.

However, ‘The most important thing’, they say, ‘is to find

the optimal time to order each item. Short lead times are

not always best. With some high-volume fashion basics, it

is to our advantage to place orders far in advance. Trendier

garments require considerably shorter lead times.’

Zara’s lead times are said to be the fastest in the indus-

try, with a ‘catwalk to rack’ time of as little of as 15 days.

According to one analyst this is because they ‘owned

most of the manufacturing capability used to make their

products, which they use as a means of exciting and

stimulating customer demand’. About half of Zara’s pro-

ducts are produced in its network of 20 Spanish factories,

which, like at Benetton, tended to concentrate on the more

capital-intensive operations such as cutting and dyeing.

Subcontractors are used for most labour-intensive opera-

tions like sewing. Zara buy around 40 per cent of its fabric

from its own wholly owned subsidiary, most of which is in

undyed form for dyeing after assembly. Most Zara factories

and their subcontractors work on a single-shift system to

retain some volume flexibility.

Distribution

Both Benetton and Zara have invested in highly automated

warehouses, close to their main production centres that

store, pack and assemble individual orders for their retail

networks. These automated warehouses represent a major

investment for both companies. In 2001, Zara caused

some press comment by announcing that it would open

a second automated warehouse even though, by its own

calculations, it was only using about half its existing ware-

house capacity. More recently, Benetton caused some

controversy by announcing that it was exploring the use of

RFID tags to track its garments.

At H&M, while the stock management is primarily handled

internally, physical distribution is subcontracted. A large

part of the flow of goods is routed from production site

to the retail country via H&M’s transit terminal in Hamburg.

Upon arrival the goods are inspected and allocated to the

stores or to the centralized store stockroom. The centralized

Chapter 13 Supply chain planning and control

403

➔

M13_SLAC0460_06_SE_C13.QXD 10/20/09 9:45 Page 403