Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

‘measurement’ could be regarded as indicating a somewhat spurious degree of accuracy.

Formally, work measurement is defined as ‘the process of establishing the time for a qualified

worker, at a defined level of performance, to carry out a specified job’. Although not a precise

definition, generally it is agreed that a specified job is one for which specifications have been

established to define most aspects of the job. A qualified worker is ‘one who is accepted as

having the necessary physical attributes, intelligence, skill, education and knowledge to per-

form the task to satisfactory standards of safety, quality and quantity’. Standard performance

is ‘the rate of output which qualified workers will achieve without over-exertion as an average

over the working day provided they are motivated to apply themselves to their work’.

The techniques of work measurement

At one time, work measurement was firmly associated with an image of the ‘efficiency expert’,

‘time and motion’ man or ‘rate fixer’, who wandered around factories with a stopwatch, look-

ing to save a few cents or pennies. And although that idea of work measurement has (almost)

died out, the use of a stopwatch to establish a basic time for a job is still relevant, and used in

a technique called ‘time study’. Time study and the general topic of work measurement are

treated in the supplement to this chapter – work study.

As well as time study, there are other work measurement techniques in use. They include

the following.

● Synthesis from elemental data is a work measurement technique for building up the time

for a job at a defined level of performance by totalling element times obtained previously

from the studies in other jobs containing the elements concerned or from synthetic data.

● Predetermined motion-time systems (PMTS) is a work measurement technique whereby

times established for basic human motions (classified according to the nature of the

motion and the conditions under which it is made) are used to build up the time for a job

at a defined level of performance.

● Analytical estimating is a work measurement technique which is a development of

estimating whereby the time required to carry out the elements of a job at a defined level

of performance is estimated from knowledge and experience of the elements concerned.

● Activity sampling is a technique in which a large number of instantaneous observations are

made over a period of time of a group of machines, processes or workers. Each observa-

tion records what is happening at that instant and the percentage of observations recorded

for a particular activity or delay is a measure of the percentage of time during which that

activity or delay occurs.

Qualified worker

Defined level of

performance

Specified job

Standard performance

Synthesis from elemental

data

Predetermined motion-

time systems

Analytical estimating

Activity sampling

Part Two Design

254

The criticisms aimed at work measurement are many and various. Amongst the most

common are the following:

● All the ideas on which the concept of a standard time is based are impossible to define

precisely. How can one possibly give clarity to the definition of qualified workers, or

specified jobs, or especially a defined level of performance?

● Even if one attempts to follow these definitions, all that results is an excessively rigid

job definition. Most modern jobs require some element of flexibility, which is difficult to

achieve alongside rigidly defined jobs.

● Using stopwatches to time human beings is both degrading and usually counter-

productive. At best it is intrusive, at worst it makes people into ‘objects for study’.

● The rating procedure implicit in time study is subjective and usually arbitrary. It has no

basis other than the opinion of the person carrying out the study.

● Time study, especially, is very easy to manipulate. It is possible for employers to ‘work

back’ from a time which is ‘required’ to achieve a particular cost. Also, experienced staff

can ‘put on an act’ to fool the person recording the times.

Critical commentary

M09A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09A.QXD 10/20/09 9:31 Page 254

Chapter 9 People, jobs and organization

255

Summary answers to key questions

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment questions

and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an eBook – all at

www.myomlab.com.

➤ Why are people issues so important in operations management?

● Human resources are any organization’s and therefore any operation’s greatest asset. Often,

most ‘human resources’ are to be found in the operations function.

➤ How do operations managers contribute to human resource strategy?

● Human resource strategy is the overall long-term approach to ensuring that an organization’s

human resources provide a strategic advantage. It involves identifying the number and type of

people that are needed to manage, run and develop the organization so that it meets its strategic

business objectives, and putting in place the programmes and initiatives that attract, develop

and retain appropriate staff. It involves being a strategic partner, an administrative expert, an

employee champion and a change agent.

➤ What forms can organization designs take?

● One can take various perspectives on organizations. How we illustrate organizations says much

about our underlying assumptions of what an ‘organization’ is. For example, organizations can

be described as machines, organisms, brains, cultures or political systems.

● There are an almost infinite number of possible organizational structures. Most are blends of

two or more ‘pure types’, such as

– The U-form

– The M-form

– Matrix forms

– The N-form.

➤ How do we go about designing jobs?

● There are many influences on how jobs are designed. These include the following:

– the division of labour

– scientific management

– method study

– work measurement

– ergonomics

– behavioural approaches, including job rotation, job enlargement and job enrichment

– empowerment

– team-working, and

– flexible working.

➤ How are work times allocated?

● The best-known method is time study, but there are other work measurement techniques,

including:

– Synthesis from elemental data

– Predetermined motion-time systems (PMTS)

– Analytical estimating

– Activity sampling.

M09A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09A.QXD 10/20/09 9:31 Page 255

Part Two Design

256

By Dr Ran Bhamra, Lecturer in Engineering Management,

Loughborough University.

‘I’m not sure why we’ve never succeeded in really get-

ting an improvement initiative to take hold in this company.

It isn’t that we haven’t been trying. TQM, Lean, even a

limited attempt to adopt Six Sigma; we’ve tried them all.

I guess that we just haven’t yet found the right approach

that fits us. That is why we’re quite excited about what we

saw at Happy Products’ (James Broadstone, Operations

Director, Service Adhesives Limited).

Service Adhesives Ltd was a mid-sized company

founded over twenty years ago to produce specialist

adhesives, mainly used in the fast-moving consumer goods

(FMCG) business, where any adhesive had to be guaranteed

‘non-irritating’ (for example in personal care products) and

definitely ‘non-toxic’ (for example in food-based products).

Largely because of its patented adhesive formulation, and

its outstanding record in developing new adhesive pro-

ducts, it has always been profitable. Yet, although its sales

revenue had continued to rise, the last few years had seen

a slowdown in the company’s profit margins. According

to Service Adhesives senior management there were

two reasons for this: first, production costs were rising

more rapidly than sales revenues, second, product quality,

while acceptable, was no longer significantly better than

competitors’. These issues had been recognized by senior

management for a number of years and several improve-

ment initiatives, focusing on product quality and process

improvement, had attempted to reverse their declining posi-

tion relative to competitors. However, none of the initiatives

had fully taken hold and delivered as promised.

In recent years, Service Adhesives Ltd had tried to

embrace a number of initiatives and modern operations

philosophies such as TQM (Total Quality Management)

and Lean; all had proved disappointing, with little resulting

change within the business. It was never clear why these

steps towards modern ways of working had not been

successful. Some senior management viewed the staff as

being of ‘below-average’ skills and motivation, and very

reluctant to change. There was a relatively high staff turn-

over rate and the company had recently started employing

short-term contract labour as an answer to controlling

its fluctuating orders. The majority of the short-term staff

were from eastern European Union member states such as

Poland and the Czech Republic and accounted for almost

20% of the total shop-floor personnel. There had been

some issues with temporary staff not adhering to quality

procedures or referring to written material, all of which was

written in English. Despite this, the company’s manage-

ment saw the use of migrant labour as largely positive:

they were hard-working and provided an opportunity to

Case study

Service Adhesives tries again

13

save costs. However, there had been some tension between

temporary and permanent employees over what was seen

as a perceived threat to their jobs.

James Broadstone, the Operations Director of Service

Adhesives, was particularly concerned about the failure

of their improvement initiatives and organized a number of

visits to other companies with similar profiles and also to a

couple of Service Adhesives, customers. It was a visit to one

of their larger customers, called (bizarrely) ‘Happy Products’

that had particularly enthused the senior management

team. ‘It was like entering another world. Their processes

are different from ours, but not that different. But their plant

was cleaner, the flow of materials seemed smoother, their

staff seemed purposeful, and above all, it seemed efficient

and a happy place to work. Everybody really did work as

a team. I think we have a lot to learn from them. I’m sure

that a team-based approach could be implemented just as

successfully in our plant’ (James Broadstone).

Happy Products were a global company and the market

leaders in their field. And although their various plants in

different parts of the world had slightly different approaches

to how they organized their production operations, the group

as a whole had a reputation for excellent human resource

management. The plant visited by Service Adhesives was

in the third year of a five-year programme to introduce and

embed a team-based work structure and culture. It had

won the coveted international ‘Best Plant in Division’ award

twice within three years. The clear driver of this success

had been identified by the award-judging panel as its

implementation of a team-based work structure. The Happy

Products plant operated a three-shift system over a 24/7

operation cycle making diapers (nappies) and health-care

products and was organized into three distinct product

areas, each containing at least two production lines utilizing

highly complex technology. Each production line was staffed

by five operators (with additional support staff serving the

whole plant). One operator was a team leader responsible

for ‘first-line management’. A second operator was a spe-

cially trained health and safety representative. A third was

a trained quality representative who also liaised with the

Quality Department. A fourth operator was a trained main-

tenance engineer, while a fifth was a non-specialist, ‘floating’

M09A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09A.QXD 10/20/09 9:31 Page 256

operator. The team had support from the production pro-

cess engineering, quality and logistics departments.

Most problems encountered in the day-to-day opera-

tion of the line could be dealt with immediately, on the line.

This ensured that production output, product quality and

line efficiency were controlled exceptionally well. Individual

team roles enabled team members to contribute and take

great satisfaction in the knowledge that they played a

key part in the success of the organization. The team spe-

cialist roles also gave the opportunity for networking with

counterparts in other plants across the world. This inter-

national communication was encouraged and added to

the sense of belonging and organizational goal orientation.

Teams were also involved in determining annual perform-

ance targets for their specific areas. Annually, corporate

strategy identified business direction, and developed per-

formance requirements for each business division which,

in turn, filtered down to individual plants. Plants devised

strategic targets for their sections and the teams them-

selves created a list of projects and activities to meet

(and hopefully exceed) targets. In this way the individual

operator on the shop floor had direct influence over their

future and the future of their business.

So impressed were Service Adhesives with what

they perceived to be a world-class operation, that they

decided that they should also consider following a similar

path towards a team-based work organization. They were

obviously missing the organizational ‘cohesiveness’ that

their customer seemed to be demonstrating. Until that

time, however, the management at Service Adhesives Ltd

had prided themselves on their traditional, hierarchical

organization structure. The organization had five layers of

operational management from the plant director at the top

to the shop floor operatives at the bottom. The chain of

command was strictly enforced by operating procedures

entwined with their long-established and comprehensive

quality assurance system. Now, it seemed, a very different

approach was needed. ‘We are very interested in learn-

ing from the visit. We have to change the way we work

and make some radical improvements to our organization’s

operational effectiveness. I have come to believe that we

have fallen behind in our thinking. A new kind of organiza-

tional culture is needed for these challenging times and

we must respond by learning from the best practice that

we can find. We also must be seen by our customers as

forward thinking. We have to prove that we are in the same

league as the “big boys”’ (James Broadstone).

At the next top team meeting, Service formally committed

itself to adopting a ‘team-based organizational structure’

with the aim of ‘establishing a culture of improvement and

operational excellence’.

Questions

1 Service Adhesives Ltd currently employs up to 20%

of their workforce on short-term contracts. What effect

will this have on the proposed team-based working

structure?

2 In considering a transition from a traditional

organizational work structure to a team-based work

structure, what sort of barriers are Service Adhesives

Ltd likely to encounter? Think about formal structures

(e.g. roles and procedures) and informal structures

(e.g. social groups and communication).

3 Senior management of Service Adhesives thought

that the reason for ineffective improvement initiatives

in the past was due mainly to the apparent lack of

cohesion amongst the organization’s human resource.

Could a team-based work organization be the answer

to their organizational difficulties? Why do think that

previous initiatives at Super Supply had failed?

4 Employee empowerment is a key element of

team-based working; what difficulties could Service

Adhesives face in implementing empowerment?

Chapter 9 People, jobs and organization

257

These problems and applications will help to improve your analysis of operations. You

can find more practice problems as well as worked examples and guided solutions on

MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com.

A hotel has two wings, an east wing and a west wing. Each wing has 4 ‘room service maids’ working 7-hour

shifts to service the rooms each day. The east wing has 40 standard rooms, 12 de luxe rooms and 5 suites. The

west wing has 50 standard rooms and 10 de luxe rooms. The standard times for servicing rooms are as follows:

standard rooms 20 standard minutes, de luxe rooms 25 standard minutes, and suites 40 standard minutes. In

addition, an allowance of 5 standard minutes per room is given for any miscellaneous jobs such as collecting

extra items for the room or dealing with customer requests. What is the productivity of the maids in each wing

of the hotel? What other factors might also influence the productivity of the maids?

In the example above, one of the maids in the west wing wants to job-share with his partner, each working

3 hours per day. His colleagues have agreed to support him and will guarantee to service all the rooms in the

west wing to the same standard each day. If they succeed in doing this, how has it affected their productivity?

2

1

Problems and applications

➔

M09A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09A.QXD 10/20/09 9:31 Page 257

Step 1 – Make a sandwich (any type of sandwich, preferably one that you enjoy) and document the task you

have to perform in order to complete the job. Make sure you include all the activities including the movement

of materials (bread etc.) to and from the work surface.

Step 2 – So impressed were your friends with the general appearance of your sandwich that they have

persuaded you to make one each for them every day. You have ten friends so every morning you must make

ten identical sandwiches (to stop squabbling). How would you change the method by which you make the

sandwiches to accommodate this higher volume?

Step 3 – The fame of your sandwiches had spread. You now decide to start a business making several different

types of sandwich in high volume. Design the jobs of the two or three people who will help you in this venture.

Assume that volumes run into at least 100 of three types of sandwich every day.

A little-known department of your local government authority has the responsibility for keeping the area’s public

lavatories clean. It employs ten people who each have a number of public lavatories that they visit and clean

and report any necessary repairs every day. Draw up a list of ideas for how you would keep this fine body of

people motivated and committed to performing this unpleasant task.

Visit a supermarket and observe the people who staff the checkouts.

(a) What kind of skills do people who do this job need to have?

(b) How many customers per hour are they capable of ‘processing’?

(c) What opportunities exist for job enrichment in this activity?

(d) How would you ensure motivation and commitment amongst the staff who do this job?

5

4

3

Part Two Design

258

Apgar, M. (1998) The alternative workplace: changing where

and how people work, Harvard Business Review, May–June.

Interesting perspective on homeworking and teleworking

amongst other things.

Argyris, C. (1998) Empowerment: the emperor’s new clothes,

Harvard Business Review, May–June. A critical but fascinat-

ing view of empowerment.

Bond, F.W. and Bunce, D. (2001) Job control mediates change

in a work reorganization intervention for stress reduction,

Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, vol. 6, 290–302.

Bridger, R. (2003) Introduction to Ergonomics, Taylor & Francis,

London. Exactly what it says in the title, an introduction

(but a good one) to ergonomics. A revised edition of a

core textbook that gives a comprehensive introduction to

ergonomics.

Hackman, R.J. and Oldham, G. (1980) Work Redesign,

Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass. Somewhat dated but, in

its time, ground-breaking and certainly hugely influential.

Herzberg, F. (1987) One more time: how do you motivate

employees? (with retrospective commentary), Harvard

Business Review, vol. 65, no. 5. An interesting look back

by one of the most influential figures in the behavioural

approach to job design school.

Lantz, A. and Brav, A. (2007) Job design for learning in work

groups, Journal of Workplace Learning, vol. 19, issue 5,

269–85.

Selected further reading

www.bpmi.org Site of the Business Process Management

Initiative. Some good resources including papers and articles.

www.bptrends.com News site for trends in business process

management generally. Some interesting articles.

www.bls.gov/oes/ US Department of Labor employment

statistics.

www.fedee.com/hrtrends Federation of European Em-

ployers guide to employment and job trends in Europe.

www.waria.com A Workflow and Reengineering Association

web site. Some useful topics.

www.opsman.org Lots of useful stuff.

Useful web sites

Now that you have finished reading this chapter, why not visit MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com where you’ll find more learning resources to help you

make the most of your studies and get a better grade?

M09A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09A.QXD 10/20/09 9:31 Page 258

Supplement to

Chapter 9

Work study

Introduction

A tale is told of Frank Gilbreth (the founder of method study) addressing a scientific confer-

ence with a paper entitled ‘The best way to get dressed in a morning’. In his presentation,

he rather bemused the scientific audience by analysing the ‘best’ way of buttoning up one’s

waistcoat in the morning. Among his conclusions was that waistcoats should always be but-

toned from the bottom upwards. (To make it easier to straighten his tie in the same motion;

buttoning from the top downwards requires the hands to be raised again.) Think of this

example if you want to understand scientific management and method study in particular.

First of all, he is quite right. Method study and the other techniques of scientific management

may often be without any intellectual or scientific validation, but by and large they work in

their own terms. Second, Gilbreth reached his conclusion by a systematic and critical analysis

of what motions were necessary to do the job. Again, these are characteristics of scientific

management – detailed analysis and painstakingly systematic examination. Third (and

possibly most important), the results are relatively trivial. A great deal of effort was put into

reaching a conclusion that was unlikely to have any earth-shattering consequences. Indeed,

one of the criticisms of scientific management, as developed in the early part of the twentieth

century, is that it concentrated on relatively limited, and sometimes trivial, objectives.

The responsibility for its application, however, has moved away from specialist ‘time and

motion’ staff to the employees who can use such principles to improve what they do and

how they do it. Further, some of the methods and techniques of scientific management, as

opposed to its philosophy (especially those which come under the general heading of

‘method study’), can in practice prove useful in critically re-examining job designs. It is the

practicality of these techniques which possibly explains why they are still influential in job

design almost a century after their inception.

Method study in job design

Method study is a systematic approach to finding the best method. There are six steps:

1 Select the work to be studied.

2 Record all the relevant facts of the present method.

3 Examine those facts critically and in sequence.

4 Develop the most practical, economic and effective method.

5 Install the new method.

6 Maintain the method by periodically checking it in use.

Step 1 – Selecting the work to be studied

Most operations have many hundreds and possibly thousands of discrete jobs and activities

which could be subjected to study. The first stage in method study is to select those jobs

to be studied which will give the most return on the investment of the time spent studying

M09B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09B.QXD 10/20/09 9:32 Page 259

them. This means it is unlikely that it will be worth studying activities which, for example,

may soon be discontinued or are only performed occasionally. On the other hand, the types

of job which should be studied as a matter of priority are those which, for example, seem

to offer the greatest scope for improvement, or which are causing bottlenecks, delays or

problems in the operation.

Step 2 – Recording the present method

There are many different recording techniques used in method study. Most of them:

● record the sequence of activities in the job;

● record the time interrelationship of the activities in the job; or

● record the path of movement of some part of the job.

Perhaps the most commonly used recording technique in method study is process mapping,

which was discussed in Chapter 4. Note that we are here recording the present method of

doing the job. It may seem strange to devote so much time and effort to recording what

is currently happening when, after all, the objective of method study is to devise a better

method. The rationale for this is, first of all, that recording the present method can give a

far greater insight into the job itself, and this can lead to new ways of doing it. Second,

recording the present method is a good starting point from which to evaluate it critically

and therefore improve it. In this last point the assumption is that it is easier to improve the

method by starting from the current method and then criticizing it in detail than by starting

with a ‘blank sheet of paper’.

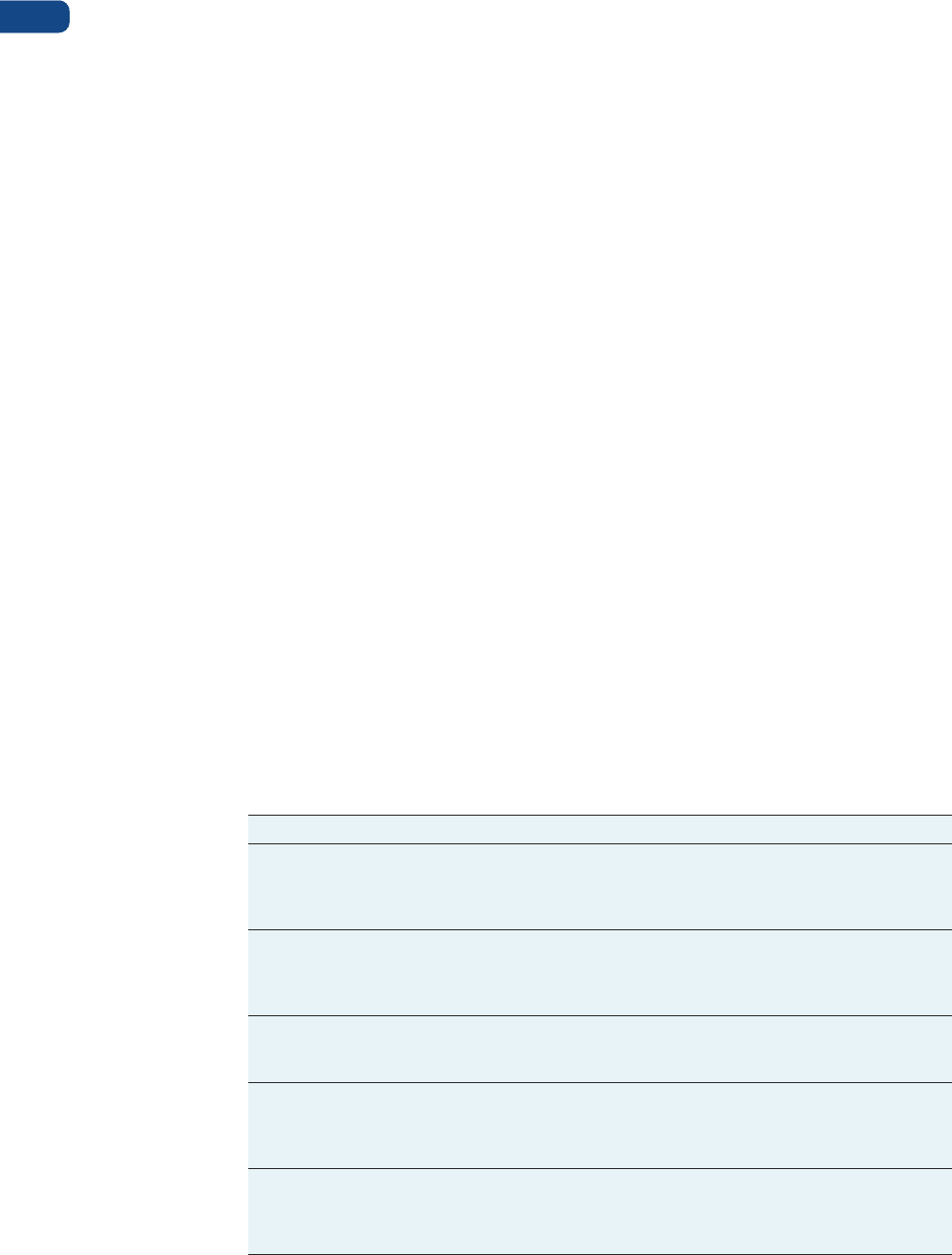

Step 3 – Examining the facts

This is probably the most important stage in method study and the idea here is to examine

the current method thoroughly and critically. This is often done by using the so-called

‘questioning technique’. This technique attempts to detect weaknesses in the rationale for

existing methods so that alternative methods can be developed (see Table S9.1). The approach

Part Two Design

260

Table S9.1 The method study questioning technique

Broad question

The purpose of each activity (questions the fundamental need

for the element)

The place in which each element is done (may suggest a

combination of certain activities or operations)

The sequence in which the elements are done (may suggest

a change in the sequence of the activity)

The person who does the activity (may suggest a combination

and/or change in responsibility or sequence)

The means by which each activity is done (may suggest

new methods)

Detailed question

What is done?

Why is it done?

What else could be done?

What should be done?

Where is it done?

Why is it done there?

Where else could it be done?

Where should it be done?

When is it done?

Why is it done then?

When should it be done?

Who does it?

Why does that person do it?

Who else could do it?

Who should do it?

How is it done?

Why is it done in that way?

How else could it be done?

How should it be done?

M09B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09B.QXD 10/20/09 9:32 Page 260

Supplement to Chapter 9 Work study

261

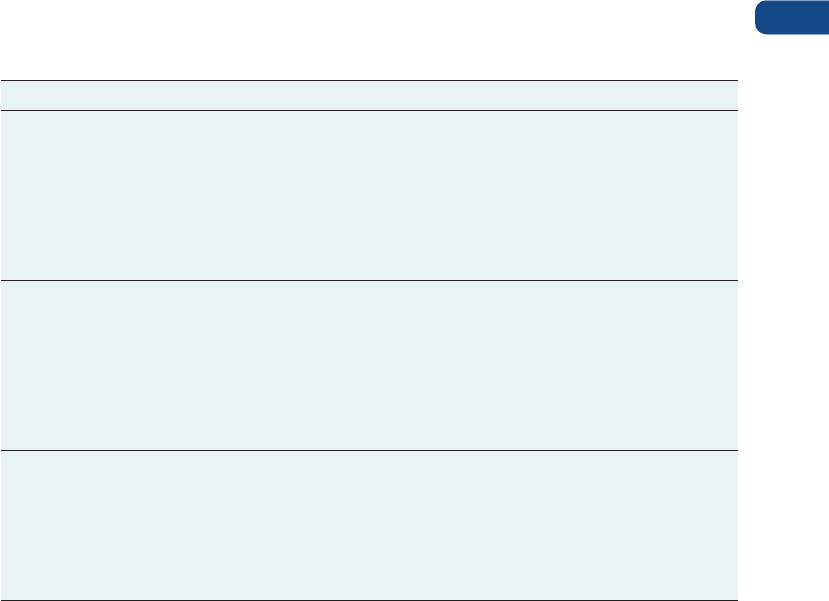

Table S9.2 The principles of motion economy

Broad principle

Use the human body the

way it works best

Arrange the workplace to

assist performance

Use technology to reduce

human effort

Source: Adapted from Barnes, Frank C. (1983) Principles of motion economy: revisited, reviewed, and restored,

Proceedings of the Southern Management Association Annual Meeting (Atlanta, GA 1983), p. 298.

How to do it

• Work should be arranged so that a natural rhythm can

become automatic

• Motion of the body should be simultaneous and symmetrical

if possible

• The full capabilities of the human body should be employed

• Arms and hands as weights are subject to the physical laws

and energy should be conserved

• Tasks should be simplified

• There should be a defined place for all equipment and

materials

• Equipment, materials and controls should be located close to

the point of use

• Equipment, materials and controls should be located to

permit the best sequence and path of motions

• The workplace should be fitted both to the tasks and to

human capabilities

• Work should be presented precisely where needed

• Guides should assist in positioning the work without close

operator attention

• Controls and foot-operated devices can relieve the hands

of work

• Mechanical devices can multiply human abilities

• Mechanical systems should be fitted to human use

may appear somewhat detailed and tedious, yet it is fundamental to the method study

philosophy – everything must be critically examined. Understanding the natural tendency to

be less than rigorous at this stage, some organizations use pro forma questionnaires, asking

each of these questions and leaving space for formal replies and/or justifications, which the

job designer is required to complete.

Step 4 – Developing a new method

The previous critical examination of current methods has by this stage probably indic-

ated some changes and improvements. This step involves taking these ideas further in an

attempt to:

● eliminate parts of the activity altogether;

● combine elements together;

● change the sequence of events so as to improve the efficiency of the job; or

● simplify the activity to reduce the work content.

A useful aid during this process is a checklist such as the revised principles of motion economy.

Table S9.2 illustrates these.

Steps 5 and 6 – Install the new method and regularly

maintain it

The method study approach to the installation of new work practices concentrates largely on

‘project managing’ the installation process. It also emphasizes the need to monitor regularly

the effectiveness of job designs after they have been installed.

Principles of motion

economy

M09B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09B.QXD 10/20/09 9:32 Page 261

Part Two Design

262

Work measurement in job design

Basic times

Terminology is important in work measurement. When a qualified worker is working on a

specified job at standard performance, the time he or she takes to perform the job is called the

basic time for the job. Basic times are useful because they are the ‘building blocks’ of time

estimation. With the basic times for a range of different tasks, an operations manager can

construct a time estimate for any longer activity which is made up of the tasks. The best-known

technique for establishing basic times is probably time study.

Time study

Time study is, ‘a work measurement technique for recording the times and rate of working

for the elements of a specified job, carried out under specified conditions, and for analysing

the data so as to obtain the time necessary for the carrying out of the job at a defined level

of performance’. The technique takes three steps to derive the basic times for the elements of

the job:

● observing and measuring the time taken to perform each element of the job;

● adjusting, or ‘normalizing’, each observed time;

● averaging the adjusted times to derive the basic time for the element.

Step 1 – Observing, measuring and rating

A job is observed through several cycles. Each time an element is performed, it is timed using

a stopwatch. Simultaneously with the observation of time, a rating of the perceived perform-

ance of the person doing the job is recorded. Rating is, ‘the process of assessing the worker’s

rate of working relative to the observer’s concept of the rate corresponding to standard

performance. The observer may take into account, separately or in combination, one or

more factors necessary to carrying out the job, such as speed of movement, effort, dexterity,

consistency, etc.’ There are several ways of recording the observer’s rating. The most common

is on a scale which uses a rating of 100 to represent standard performance. If an observer rates

a particular observation of the time to perform an element at 100, the time observed is the

actual time which anyone working at standard performance would take.

Step 2 – Adjusting the observed times

The adjustment to normalize the observed time is:

where standard rating is 100 on the common rating scale we are using here. For example, if

the observed time is 0.71 minute and the observed rating is 90, then:

Basic time ==0.64 min

Step 3 – Average the basic times

In spite of the adjustments made to the observed times through the rating mechanism,

each separately calculated basic time will not be the same. This is not necessarily a function

of inaccurate rating, or even the vagueness of the rating procedure itself; it is a natural

phenomenon of the time taken to perform tasks. Any human activity cannot be repeated in

exactly the same time on every occasion.

0.71 × 90

100

observed rating

standard rating

Basic time

Time study

Rating

M09B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09B.QXD 10/20/09 9:32 Page 262

Standard times

The standard time for a job is an extension of the basic time and has a different use. Whereas the

basic time for a job is a piece of information which can be used as the first step in estimating the

time to perform a job under a wide range of conditions, standard time refers to the time allowed

for the job under specific circumstances. This is because standard time includes allowances

which reflect the rest and relaxation allowed because of the conditions under which the job is

performed. So the standard time for each element consists principally of two parts, the basic

time (the time taken by a qualified worker, doing a specified job at standard performance) and

an allowance (this is added to the basic time to allow for rest, relaxation and personal needs).

Allowances

Allowances are additions to the basic time intended to provide the worker with the opportun-

ity to recover from the physiological and psychological effects of carrying out specified work

under specified conditions and to allow for personal needs. The amount of the allowance

will depend on the nature of the job. The way in which relaxation allowance is calculated,

and the exact allowances given for each of the factors which determine the extent of the

allowance, vary between different organizations. Table S9.3 illustrates the allowance table

used by one company which manufactures domestic appliances. Every job has an allowance

of 10%; the table shows the further percentage allowances to be applied to each element of

the job. In addition, other allowances may be applied for such things as unexpected con-

tingencies, synchronization with other jobs, unusual working conditions, and so on.

Figure S9.1 shows how average basic times for each element in the job are combined with

allowances (low in this example) for each element to build up the standard time for the

whole job.

Standard time

Allowances

Supplement to Chapter 9 Work study

263

Table S9.3 An allowances table used by a domestic appliance manufacturer

Allowance factors Example Allowance (%)

Energy needed

Negligible none 0

Very light 0–3 kg 3

Light 3–10 kg 5

Medium 10–20 kg 10

Heavy 20–30 kg 15

Very heavy Above 30 kg 15–30

Posture required

Normal Sitting 0

Erect Standing 2

Continuously erect Standing for long periods 3

Lying On side, face or back 4

Difficult Crouching, etc. 4–10

Visual fatigue

Nearly continuous attention 2

Continuous attention with varying focus 3

Continuous attention with fixed focus 5

Temperature

Very low Below 0 °C over 10

Low 0–12 °C 0–10

Normal 12–23 °C 0

High 23–30 °C 0–10

Very high Above 30 °C over 10

Atmospheric conditions

Good Well ventilated 0

Fair Stuffy/smelly 2

Poor Dusty/needs filter 2–7

Bad Needs respirator 7–12

M09B_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09B.QXD 10/20/09 9:32 Page 263