Nigel S., Chambers S., Johnson R. Operations Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Does the technology give an acceptable financial return?

Assessing the financial value of investing in process technology is in itself a specialized subject.

And while it is not the purpose of this book to delve into the details of financial analysis,

it is important to highlight one important issue that is central to financial evaluation: while

the benefits of investing in new technology can be spread over many years into the future,

the costs associated with investing in the technology usually occur up-front. So we have to

consider the time value of money. Simply, this means that receiving a1,000 now is better

than receiving a1,000 in a year’s time. Receiving a1,000 now enables us to invest the money

so that it will be worth more than the a1,000 we receive in a year’s time. Alternatively, revers-

ing the logic, we can ask ourselves how much would have to be invested now to receive

a1,000 in one year’s time. This amount (lower than a1,000) is called the net present value of

receiving a1,000 in one year’s time.

Part Two Design

224

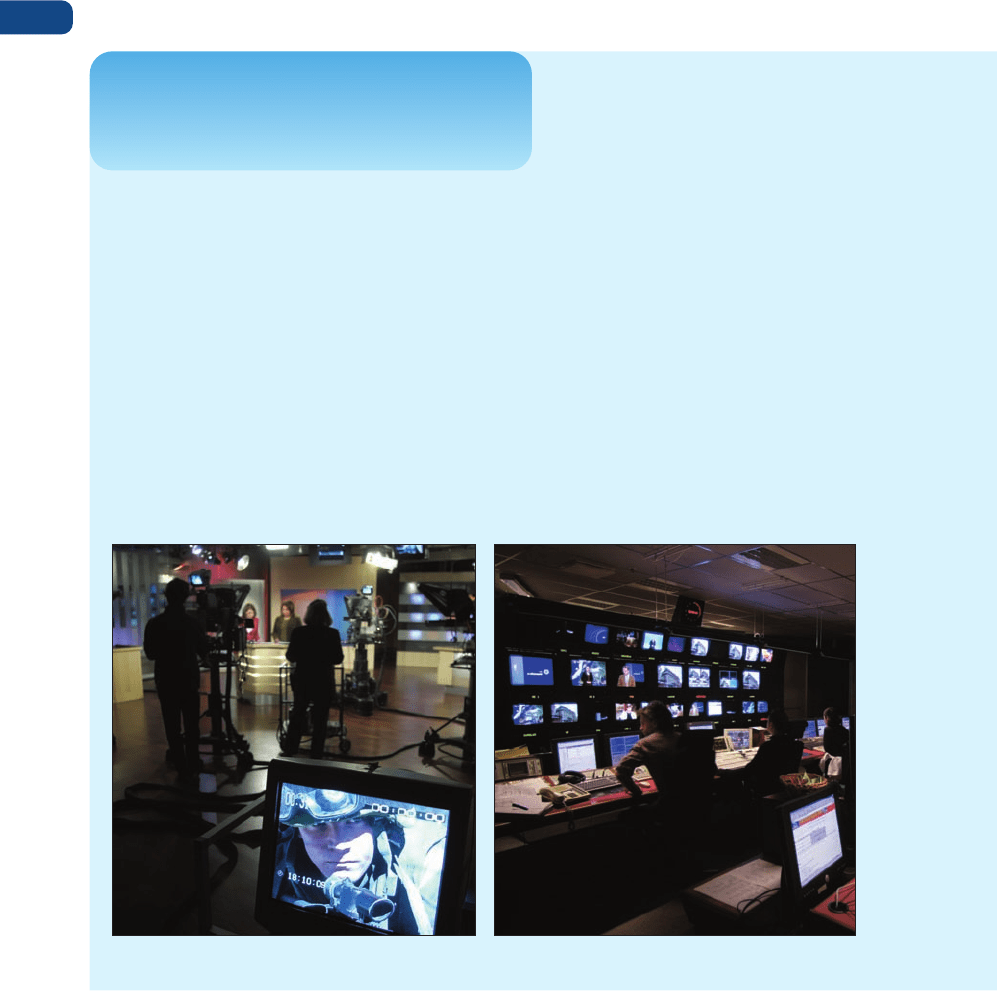

In the summer of 2000 the management of SVT

(Sveriges Television) the Swedish public-service

television company, decided to invest in a whole new

type of digital news technology. At the same time they

also decided to reorganize their news operations, move

the whole news operation to a new building and, if that

wasn’t enough, launch its own new 24-hour news

channel. This meant building a new studio facility for

11 shows (all in one huge room), moving 600 people,

building control rooms, buying and constructing new

news production hardware, and most significantly,

investing $20 million in constructing a cutting-edge digital

news production system without comparison in the world.

The hardware for this was bought ‘off the shelf’ but SVT’s

own software staff coded the software. The system also

SVT’s new technology allows it to edit studio and pre-recorded material flexibly and easily

Short case

SVT programme investment in

technology

12

allowed contributions from all regions of Sweden to be

integrated into national and local news programmes.

Together with the rebranding of the company’s news

and current affairs shows, it was the single biggest

organizational development in the history of SVT.

For many, the most obvious result of the step

change in the company’s technology was to be the

launch of its new 24-hour digital rolling news service.

This finally launched on 10 September 2001. One day

later it had to cope with the biggest news story that

had broken for decades. To the relief of all, the new

system coped. Now well bedded in, the system lets

journalists create, store and share news clips easier

and faster, with no video cassettes requiring physical

handling. Broadcast quality has also improved because

video cassettes were prone to breakdown. The

atmosphere in the control room is much calmer.

Finally, the number of staff necessary to produce the

broadcast news has decreased and resources have

been shifted into journalism.

Time value of money

Net present value

Source: SVT Bengt O Nordin

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 224

For example, suppose current interest rates are 10 per cent per annum; then the amount

we would have to invest to receive a1,000 in one year’s time is

a1,000 ×=a909.10

So the present value of a1,000 in one year’s time, discounted for the fact that we do not have

it immediately, is a909.10. In two years’ time, the amount we would have to invest to receive

a1,000 is:

a1,000 ××=a1,000 ×=a826.50

The rate of interest assumed (10 per cent in our case) is known as the discount rate. More

generally, the present value of ax in n years’ time, at a discount rate of r per cent, is:

a n

x

(1 + r/100)

1

(1.10)

2

1

(1.10)

1

(1.10)

1

(1.10)

Discount rate

Chapter 8 Process technology

225

The warehouse which we have been using as an example has been subjected to a costing

and cost savings exercise. The capital cost of purchasing and installing the new technology

can be spread over three years, and from the first year of its effective operation, overall

operations cost savings will be made. Combining the cash that the company will have to

spend and the savings that it will make, the cash flow year by year is shown in Table 8.4.

Table 8.4 Cash flows for the warehouse process technology

Year 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Cash flow (A000s) −300 30 50 400 400 400 400 0

Present value

(discounted at 10%) −300 27.27 41.3 300.53 273.21 248.37 225.79 0

However, these cash flows have to be discounted in order to assess their ‘present

value’. Here the company is using a discount rate of 10 per cent. This is also shown in

Table 8.4. The effective life of this technology is assumed to be six years:

The total cash flow (sum of all the cash flows) = a1.38 million

However, the net present value (NPV) = a816,500

This is considered to be acceptable by the company.

Calculating discount rates, although perfectly possible, can be cumbersome. As an

alternative, tables are usually used such as the one in Table 8.5.

So now the net present value, P = DF × FV

where

DF = the discount factor from Table 8.5

FV = future value

To use the table, find the vertical column and locate the appropriate discount rate (as

a percentage). Then find the horizontal row corresponding to the number of years it

will take to receive the payment. Where the column and the row intersect is the present

value of a1. You can multiply this value by the expected future value, in order to find its

present value.

Worked example

➔

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 225

Part Two Design

226

Table 8.5 Present value of A1 to be paid in future

Years 3.0% 4.0% 5.0% 6.0% 7.0% 8.0% 9.0% 10.0%

1 A0.970 A0.962 A0.952 A0.943 A0.935 A0.926 A0.918 A0.909

2 A0.942 A0.925 A0.907 A0.890 A0.873 A0.857 A0.842 A0.827

3 A0.915 A0.889 A0.864 A0.840 A0.816 A0.794 A0.772 A0.751

4 A0.888 A0.855 A0.823 A0.792 A0.763 A0.735 A0.708 A0.683

5 A0.862 A0.822 A0.784 A0.747 A0.713 A0.681 A0.650 A0.621

6 A0.837 A0.790 A0.746 A0.705 A0.666 A0.630 A0.596 A0.565

7 A0.813 A0.760 A0.711 A0.665 A0.623 A0.584 A0.547 A0.513

8 A0.789 A0.731 A0.677 A0.627 A0.582 A0.540 A0.502 A0.467

9 A0.766 A0.703 A0.645 A0.592 A0.544 A0.500 A0.460 A0.424

10 A0.744 A0.676 A0.614 A0.558 A0.508 A0.463 A0.422 A0.386

11 A0.722 A0.650 A0.585 A0.527 A0.475 A0.429 A0.388 A0.351

12 A0.701 A0.626 A0.557 A0.497 A0.444 A0.397 A0.356 A0.319

13 A0.681 A0.601 A0.530 A0.469 A0.415 A0.368 A0.326 A0.290

14 A0.661 A0.578 A0.505 A0.442 A0.388 A0.341 A0.299 A0.263

15 A0.642 A0.555 A0.481 A0.417 A0.362 A0.315 A0.275 A0.239

16 A0.623 A0.534 A0.458 A0.394 A0.339 A0.292 A0.252 A0.218

17 A0.605 A0.513 A0.436 A0.371 A0.317 A0.270 A0.231 A0.198

18 A0.587 A0.494 A0.416 A0.350 A0.296 A0.250 A0.212 A0.180

19 A0.570 A0.475 A0.396 A0.331 A0.277 A0.232 A0.195 A0.164

20 A0.554 A0.456 A0.377 A0.312 A0.258 A0.215 A0.179 A0.149

A health-care clinic is considering purchasing a new analysis system. The net cash flows

from the new analysis system are as follows.

Year 1: −a10,000 (outflow of cash)

Year 2: a3,000

Year 3: a3,500

Year 4: a3,500

Year 5: a3,000

Assuming that the real discount rate for the clinic is 9%, using the net present value table

(Table 8.6), demonstrate whether the new system would at least cover its costs. Table 8.6

shows the calculations. It shows that, because the net present value of the cash flow is

positive, purchasing the new system would cover its costs, and will be (just) profitable

for the clinic.

Table 8.6 Present value calculations for the clinic

Year Cash flow Table factor Present value

1(A10,000) × 1.000 = (A10,000.00)

2 A 3,000 × 0.917 = A2,752.29

3 A 3,500 × 0.842 = A2,945.88

4 A 3,500 × 0.772 = A2,702.64

5 A 3,000 × 0.708 = A2,125.28

Net present value = A526.09

Worked example

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 226

Chapter 8 Process technology

227

Implementing process technology

Implementating process technology means organizing all the activities involved in making

the technology work as intended. No matter how potentially beneficial and sophisticated the

technology, it remains only a prospective benefit until it has been implemented successfully.

So implementation is an important part of process technology management. Yet it is not

always straightforward to make general points about the implementation process because it

is very context-dependent. That is, the way one implements any technology will very much

depend on its specific nature, the changes implied by the technology and the organizational

conditions that apply during its implementation. In the remainder of this chapter we look at

two particularly important issues that affect technology implementation: the idea of resource

and process ‘distance’, and the idea that if anything can go wrong, it will.

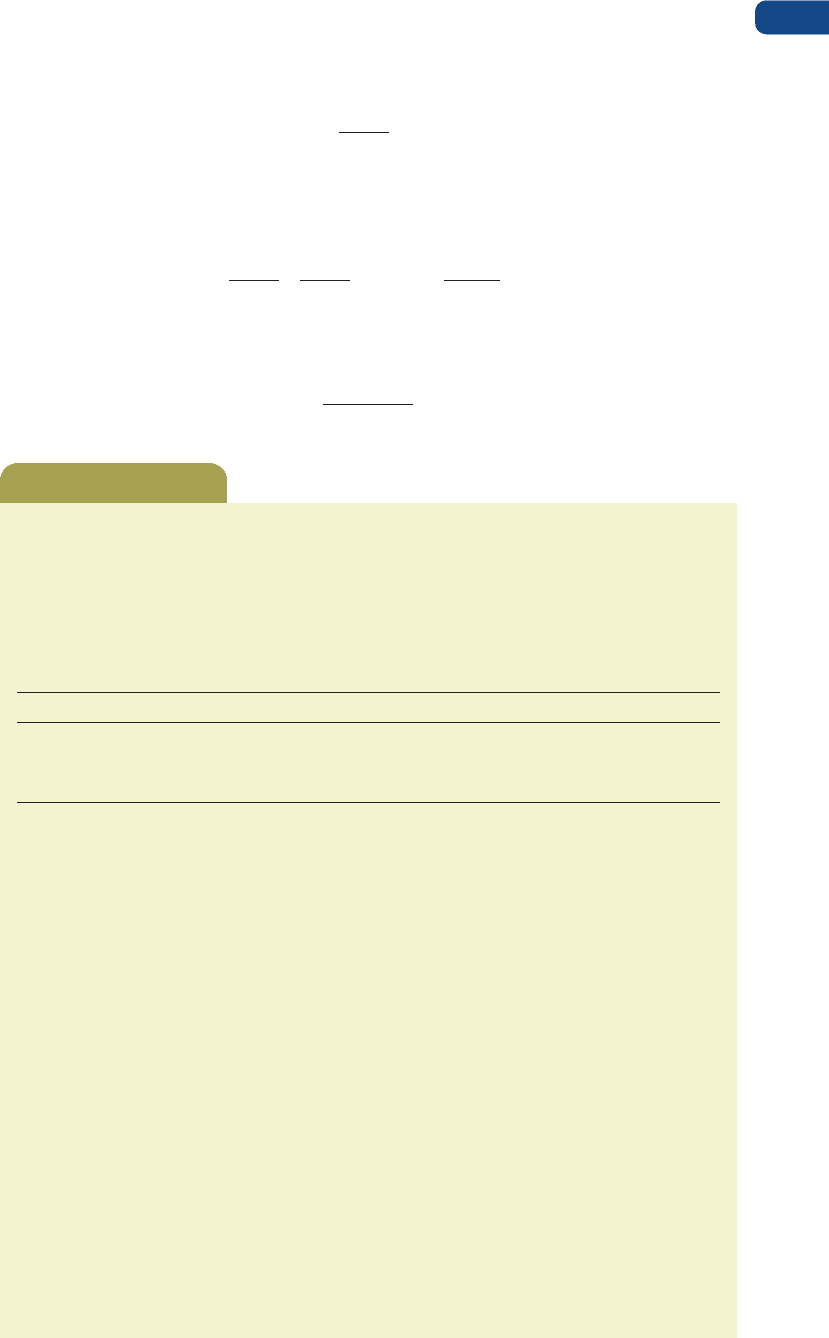

Resource and process ‘distance’

The degree of difficulty in the implementation of process technology will depend on the degree

of novelty of the new technology resources and the changes required in the operation’s

processes. The less that the new technology resources are understood (influenced perhaps by

the degree of innovation) the greater their ‘distance’ from the current technology resource

base of the operation. Similarly, the extent to which an implementation requires an operation

to modify its existing processes, the greater the ‘process distance’. The greater the resource

and process distance, the more difficult any implementation is likely to be. This is because

such distance makes it difficult to adopt a systematic approach to analysing change and learn-

ing from mistakes. Those implementations which involve relatively little process or resource

‘distance’ provide an ideal opportunity for organizational learning. As in any classic scientific

experiment, the more variables that are held constant, the more confidence you have in deter-

mining cause and effect. Conversely, in an implementation where the resource and process

‘distance’ means that nearly everything is ‘up for grabs’, it becomes difficult to know what

has worked and what has not. More importantly, it becomes difficult to know why something

has or has not worked.

13

This idea is illustrated in Figure 8.7.

Figure 8.7 Learning potential depends on both technological resource and process ‘distance’

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 227

Part Two Design

228

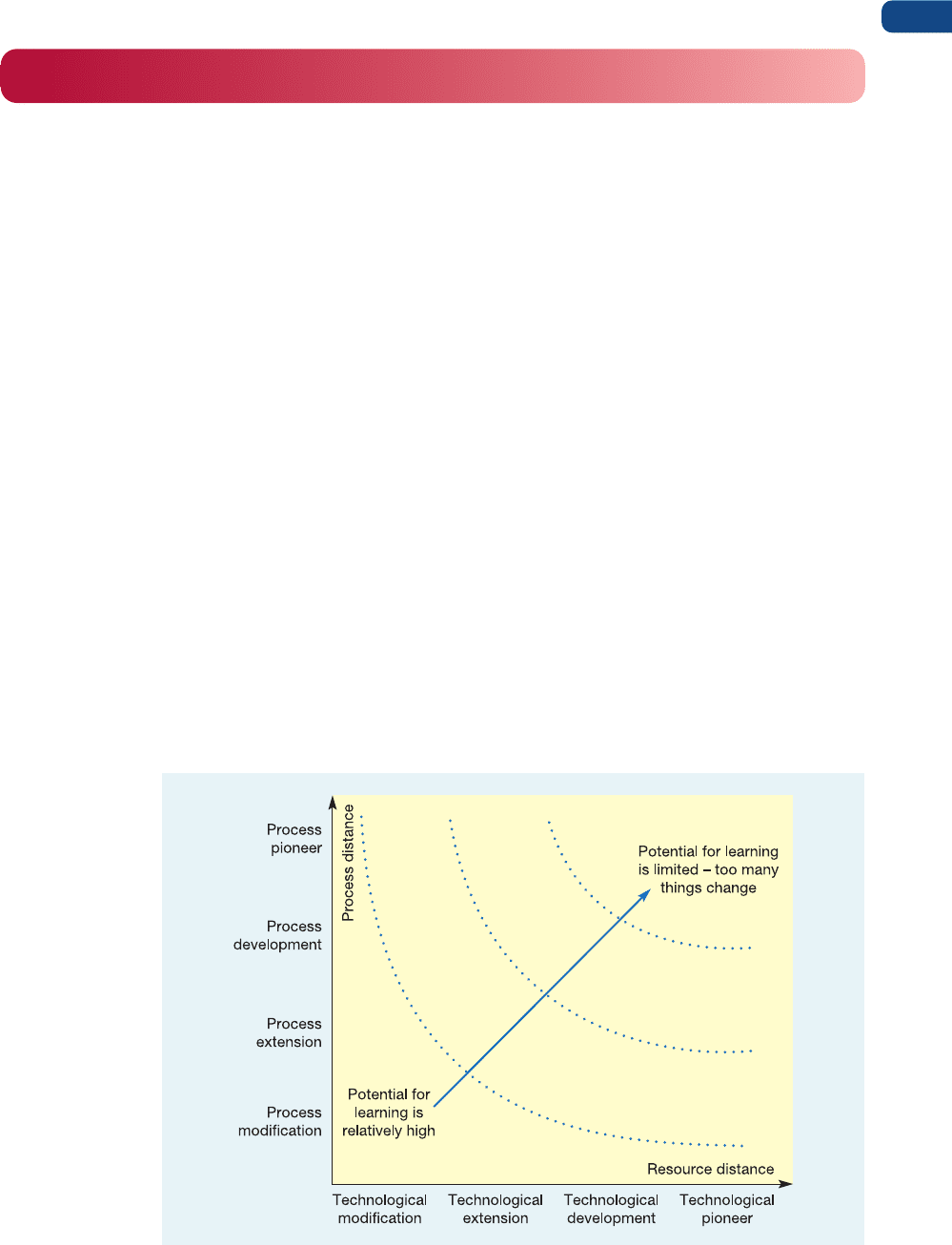

Figure 8.8 The reduction in performance during and after the implementation of a new

process reflects ‘adjustments costs’

Anticipating implementation problems

The implementation of any process technology will need to account for the ‘adjustment’ issues

that almost always occur when making any organizational change. By adjustment issues we

mean the losses that could be incurred before the improvement is functioning as intended.

But estimating the nature and extent of any implementation issues is notoriously difficult.

This is particularly true because more often than not, Murphy’s law seems to prevail. This

law is usually stated as, ‘if anything can go wrong, it will’. This effect has been identified empir-

ically in a range of operations, especially when new types of process technology are involved.

Specifically discussing technology-related change (although the ideas apply to almost any

implementation), Bruce Chew of Massachusetts Institute of Technology

14

argues that adjust-

ment ‘costs’ stem from unforeseen mismatches between the new technology’s capabilities and

needs and the existing operation. New technology rarely behaves as planned and as changes

are made their impact ripples throughout the organization. Figure 8.8 is an example of what

Chew calls a ‘Murphy curve’. It shows a typical pattern of performance reduction (in this case,

quality) as a new process technology is introduced. It is recognized that implementation may

take some time; therefore allowances are made for the length and cost of a ‘ramp-up’ period.

However, as the operation prepares for the implementation, the distraction causes perform-

ance actually to deteriorate. Even after the start of the implementation this downward trend

continues and it is only weeks, indeed maybe months, later that the old performance level is

reached. The area of the dip indicates the magnitude of the adjustment costs, and therefore

the level of vulnerability faced by the operation.

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 228

Chapter 8 Process technology

229

Summary answers to key questions

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment questions

and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an eBook – all at

www.myomlab.com.

➤ What is process technology?

● Process technology is the machines, equipment or devices that help operations to create or

deliver products and services. Indirect process technology helps to facilitate the direct creation

of products and services.

➤ How does one gain an understanding of process technologies?

● Operations managers do not need to know the technical details of all technologies, but they

do need to know the answers to the following questions. What does it do? How does it do it?

What advantages does it give? What constraints does it impose?

● Material processing technologies which have had a particular impact include numerically con-

trolled machine tools, robots, automated guided vehicles, flexible manufacturing systems and

computer-integrated manufacturing systems.

● Information processing technologies which have had a particular impact include networks,

such as local-area networks (LANs), wireless LANs and wide-area networks (WANs), the

Internet, the World Wide Web and extranets. Other developments include RFID, management

information systems, decision support systems and expert systems.

● There are no universally agreed classifications of customer-processing technologies, such

as there are with materials- and information-processing technologies. The way we classify

technologies here is through the nature of the interaction between customers, staff and the

technology itself. Using this classification, technologies can be categorized into those with

direct customer interaction and those which are operated by an intermediary.

➤ How are process technologies evaluated?

● All technologies should be appropriate for the activities that they have to undertake. In

practice this means making sure that the degree of automation of the technology, the scale or

scalability of the technology, and the degree of coupling or connectivity of the technology fit

the volume and variety characteristics of the operation.

● All technologies should be evaluated by assessing the impact that the process technology will

have on the operation’s performance objectives (quality, speed, dependability, flexibility and

cost).

● All technologies should be evaluated financially. This usually involves the use of some of the

more common evaluation approaches, such as net present value (NPV).

➤ How are process technologies implemented?

● Implementating process technology means organizing all the activities involved in making the

technology work as intended.

● The resource and process ‘distance’ implied by the technology implementation will indicate the

degree of difficulty.

● It is necessary to allow for the adjustment costs of implementation.

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 229

Part Two Design

230

Dr Rhodes was losing his temper. ‘It should be a simple

enough decision. There are only two alternatives. You are

only being asked to choose a machine!’

The Management Committee looked abashed. Rochem

Ltd was one of the largest independent companies supply-

ing the food-processing industry. Its initial success had

come with a food preservative used mainly for meat-based

products and marketed under the name of ‘Lerentyl’. Other

products were subsequently developed in the food colour-

ing and food container coating fields, so that now Lerentyl

accounted for only 25 per cent of total company sales, which

were now slightly over £10 million.

The decision

The problem over which there was such controversy related

to the replacement of one of the process units used; to

manufacture Lerentyl. Only two such units were used;

both were ‘Chemling’ machines. It was the older of the two

Chemling units which was giving trouble. High breakdown

figures, with erratic quality levels, meant that output level

requirements were only just being reached. The problem

was: should the company replace the ageing Chemling with

a new Chemling, or should it buy the only other plant on

the market capable of the required process, the ‘AFU’ unit?

The Chief Chemist’s staff had drawn up a comparison of

the two units, shown in Table 8.7.

The body considering the problem was the newly formed

Management Committee. The committee consisted of the

four senior managers in the firm: the Chief Chemist and the

Marketing Manager, who had been with the firm since its

beginning, together with the Production Manager and the

Accountant, both of whom had joined the company only

six months before.

What follows is a condensed version of the information

presented by each manager to the committee, together

with their attitudes to the decision.

Table 8.7 A comparison of the two alternative machines

CHEMLING AFU

Capital cost £590,000 £880,000

Processing costs Fixed: £15,000/month Fixed: £40,000/month

Variable: £750/kg Variable: £600/kg

Design 105 kg/month 140 kg/month

Capacity 98 ± 0.7% purity 99.5 ± 0.2% purity

Quality Manual testing Automatic testing

Maintenance Adequate but needs servicing Not known – probably good

After-sales services Very good Not known – unlikely to be good

Delivery Three months Immediate

Case study

Rochem Ltd

The marketing manager

The current market for this type of preservative had reached

a size of some £5 million, of which Rochem Ltd supplied

approximately 48 per cent. There had, of late, been signific-

ant changes in the market – in particular, many of the users

of preservatives were now able to buy products similar to

Lerentyl. The result had been the evolution of a much more

price-sensitive market than had previously been the case.

Further market projections were somewhat uncertain. It

was clear that the total market would not shrink (in volume

terms) and best estimates suggested a market of perhaps

£6 million within the next three or four years (at current

prices). However, there were some people in the industry

who believed that the present market only represented the

tip of the iceberg.

Although the food preservative market had advanced

by a series of technical innovations, ‘real’ changes in the

basic product were now few and far between. Lerentyl was

sold in either solid powder or liquid form, depending on

Source: Press Association Images

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 230

‘It’s all right for Dave and Eric [Marketing Manager and

Chief Chemist] to talk about a big expansion of Lerentyl

sales; they don’t have to cope with all the problems if it

doesn’t happen. The fixed costs of the AFU unit are nearly

three times those of the Chemling. Just think what that will

do to my budget at low volumes of output. As I understand

it, there is absolutely no evidence to show a large upswing

in Lerentyl. No, the whole idea [of the AFU plant] is just too

risky. Not only is there the risk. I don’t think it is gener-

ally understood what the consequences of the AFU would

mean. We would need twice the variety of spares for a

start. But what really worries me is the staff’s reaction. As

fully qualified technicians they regard themselves as the

elite of the firm; so they should, they are paid practically

the same as I am! If we get the AFU plant, all their most

interesting work, like the testing and the maintenance,

will disappear or be greatly reduced. They will finish up as

highly paid process workers.’

The accountant

The company had financed nearly all its recent capital

investment from its own retained profits, but would be tak-

ing out short-term loans the following year for the first time

for several years.

‘At the moment, I don’t think it wise to invest extra

capital we can’t afford in an attempt to give us extra

capacity we don’t need. This year will be an expensive one

for the company. We are already committed to consider-

ably increased expenditure on promotion of our other

products and capital investment in other parts of the firm,

and Dr Rhodes is not in favour of excessive funding from

outside the firm. I accept that there might eventually be an

upsurge in Lerentyl demand but, if it does come, it prob-

ably won’t be this year and it will be far bigger than the

AFU can cope with anyway, so we might as well have three

Chemling plants at that time.’

Questions

1 How do the two alternative process technologies

(Chemling and AFU) differ in terms of their scale

and automation? What are the implications of this

for Rochem?

2 Remind yourself of the distinction between

feasibility, acceptability and vulnerability discussed

in Chapter 4. Evaluate both technologies using

these criteria.

3 What would you recommend the company should do?

the particular needs of the customer. Prices tended to be

related to the weight of chemical used, however. Thus, for

example, the current average market price was approxim-

ately £1,050 per kg. There were, of course, wide variations

depending on order size, etc.

‘At the moment I am mainly interested in getting the right

quantity and quality of Lerentyl each month and although

Production has never let me down yet, I’m worried that

unless we get a reliable new unit quickly, it soon will. The

AFU machine could be on line in a few weeks, giving better

quality too. Furthermore, if demand does increase (but I’m

not saying it will), the AFU will give us the extra capacity.

I will admit that we are not trying to increase our share

of the preservative market as yet. We see our priority as

establishing our other products first. When that’s achieved,

we will go back to concentrating on the preservative side

of things.’

The chief chemist

The Chief Chemist was an old friend of John Rhodes

and together they had been largely responsible for every

product innovation. At the moment, the major part of his

budget was devoted to modifying basic Lerentyl so that it

could be used for more acidic food products such as fruit.

This was not proving easy and as yet nothing had come

of the research, although the Chief Chemist remained

optimistic.

‘If we succeed in modifying Lerentyl the market

opportunities will be doubled overnight and we will need

the extra capacity. I know we would be taking a risk by

going for the AFU machine, but our company has grown

by gambling on our research findings, and we must con-

tinue to show faith. Also the AFU technology is the way all

similar technologies will be in the future. We have to start

learning how to exploit it sooner or later.’

The production manager

The Lerentyl Department was virtually self-contained as a

production unit. In fact, it was physically separate, located

in a building a few yards detached from the rest of the plant.

Production requirements for Lerentyl were currently at a

steady rate of 190 kg per month. The six technicians who

staffed the machines were the only technicians in Rochem

who did all their own minor repairs and full quality control.

The reason for this was largely historical since, when the

firm started, the product was experimental and qualified

technicians were needed to operate the plant. Four of the

six had been with the firm almost from its beginning.

Chapter 8 Process technology

231

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 231

Part Two Design

232

These problems and applications will help to improve your analysis of operations. You

can find more practice problems as well as worked examples and guided solutions on

MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com.

A new machine requires an investment of A500,000 and will generate profits of A100,000 for 10 years.

Will the investment have a positive net present value assuming that a realistic interest is 6 per cent?

A local government housing office is considering investing in a new computer system for managing the

maintenance of its properties. The system is forecast to generate savings of around £100,000 per year and

will cost £400,000. It is expected to have a life of 7 years. The local authority expects its departments to use a

discount rate of 0.3 to calculate the financial return on its investments. Is this investment financially worthwhile?

In the example above, the local government’s finance officers have realized that their discount rate has been

historically too low. They now believe that the discount rate should be doubled. Is the investment in the new

computer system still worthwhile?

A new optical reader for scanning documents is being considered by a retail bank. The new system has a fixed

cost of A30,000 per year and a variable cost of A2.5 per batch. The cost of the new scanner is A100,000. The

bank charges A10 per batch for scanning documents and it believes that the demand for its scanning services

will be 2,000 batches in year 1, 5,000 batches in year 2, 10,000 batches in year 3, and then 12,000 batches per

year from year 4 onwards. If the realistic discount rate for the bank is 6 per cent, calculate the net present value

of the investment over a 5-year period.

How do you think RFID could benefit operations process in (a) a hospital, (b) an airport, (c) a warehouse?

5

4

3

2

1

Problems and applications

Brain, M. (2001) Marshall Brain’s How Stuff Works, Hungry

Minds, NY. Exactly what it says. A lot of the ‘stuff ’ is

product technology, but the book also explains many pro-

cess technologies in a clear and concise manner without

sacrificing relevant detail.

Carr, N.G. (2000) Hypermediation: ‘commerce and click-

stream’, Harvard Business Review, January–February. Written

at the height of the Internet boom, it gives a flavour of how

Internet technologies were seen.

Chew, W.B., Leonard-Barton, D. and Bohn, R.E. (1991)

Beating Murphy’s law, Sloan Management Review, vol. 5,

Spring. One of the few articles that treats the issue of why

everything seems to go wrong when any new technology is

introduced. Insightful.

Cobham, D. and Curtis, G. (2004) Business Information

Systems: Analysis, Design and Practice, Financial Times

Prentice Hall, Harlow. A good solid text on the subject.

Evans, P. and Wurster, T. (1999) Blown to Bits: How the

New Economics of Information Transforms Strategy, Harvard

Business School Press, Boston. Interesting exposition of

how Internet-based technologies can change the rules of

the game in business.

Selected further reading

www.bpmi.org Site of the Business Process Management

Initiative. Some good resources including papers and

articles.

www.opsman.org Lots of useful stuff.

www.iienet.org The American Institute of Industrial

Engineers site. An important professional body for techno-

logy, process design and related topics.

www.waria.com A Workflow and Reengineering Association

web site. Some useful topics.

Useful web sites

Now that you have finished reading this chapter, why not visit MyOMLab at

www.myomlab.com where you’ll find more learning resources to help you

make the most of your studies and get a better grade?

M08_SLAC0460_06_SE_C08.QXD 10/20/09 9:30 Page 232

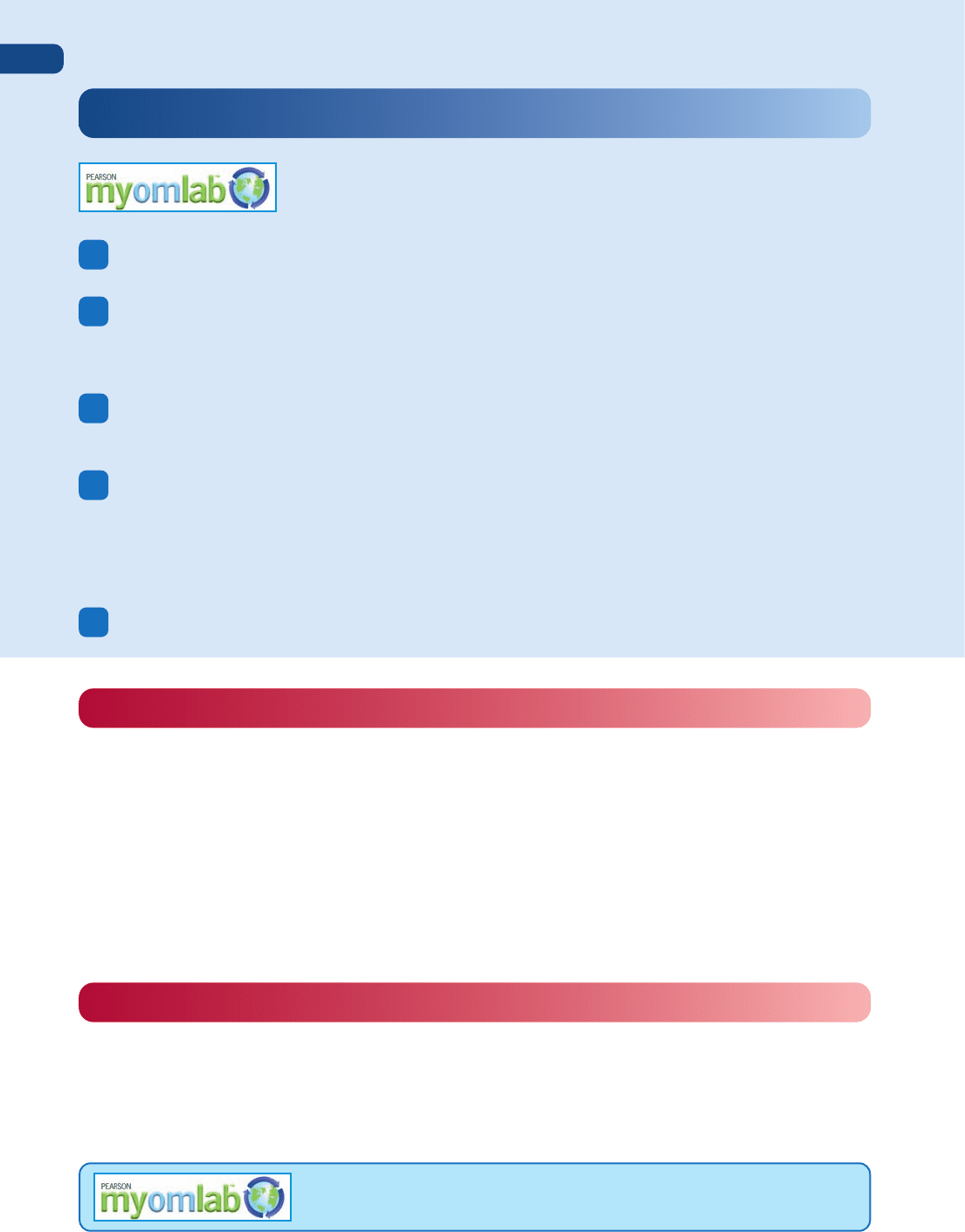

Introduction

Operations management is often presented as a subject the

main focus of which is on technology, systems, procedures and

facilities – in other words the non-human parts of the organization.

This is not true of course. On the contrary, the manner in which

an organization’s human resources are managed has a profound

impact on the effectiveness of its operations function. In this

chapter we look especially at the elements of human resource

management which are traditionally seen as being directly within

the sphere of operations management. These are, how operations

managers contribute to human resource strategy, organization

design, designing the working environment, job design, and

the allocation of ‘work times’ to operations activities. The more

detailed (and traditional) aspects of these last two elements are

discussed further in the supplement to this chapter on Work

Study. Figure 9.1 shows how this chapter fits into the overall

model of operations activities.

Chapter 9

People, jobs and

organization

Key questions

➤ Why are people issues so important

in operations management?

➤ How do operations managers

contribute to human resource

strategy?

➤ What forms can organization

designs take?

➤ How do we go about designing

jobs?

➤ How are work times allocated?

Figure 9.1 This chapter examines people, jobs and organization

Check and improve your understanding of this chapter using self assessment

questions and a personalised study plan, audio and video downloads, and an

eBook – all at www.myomlab.com.

M09A_SLAC0460_06_SE_C09A.QXD 10/20/09 9:31 Page 233