Murray J.D. Mathematical Biology: I. An Introduction

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

6 1. Continuous Population Models for Single Species

and (1.4) becomes

dN

dt

= f (N

∗

+n) ≈ f (N

∗

) +nf

(N

∗

) +···,

which to first order in n(t) gives

dN

dt

≈ nf

(N

∗

) ⇒ n(t) ∝ exp

f

N

∗

t

. (1.5)

So n grows or decays accordingly as f

(N

∗

)>0or f

(N

∗

)<0. The timescale of the

response of the population to a disturbance is of the order of 1/| f

(N

∗

) |; it is the time

to change the initial disturbance by a factor e.

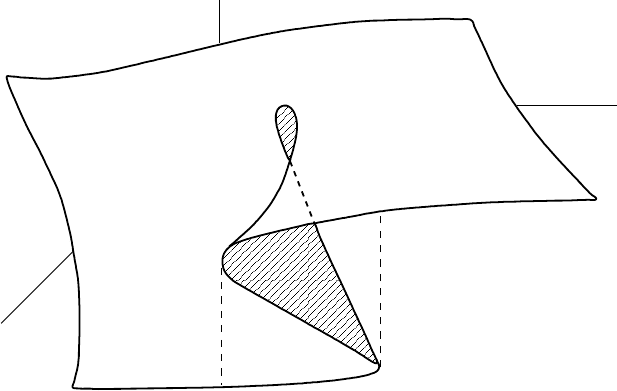

There may be several equilibrium, or steady state, populations N

∗

which are so-

lutions of f (N) = 0: it depends on the system f (N) models. Graphically plotting

f (N) against N immediately gives the equilibria as the points where it crosses the

N-axis. The gradient f

(N

∗

) at each steady state then determines its linear stability.

Such steady states may, however, be unstable to finite disturbances. Suppose, for ex-

ample, that f (N) is as illustrated in Figure 1.3. The gradients f

(N

∗

) at N = 0, N

2

are positive so these equilibria are unstable while those at N = N

1

, N

3

arestableto

small perturbations: the arrows symbolically indicate stability or instability. If, for ex-

ample, we now perturb the population from its equilibrium N

1

so that N is in the range

N

2

< N < N

3

then N → N

3

rather than returning to N

1

. A similar perturbation from

N

3

to a value in the range 0 < N < N

2

would result in N(t) → N

1

. Qualitatively

there is a threshold perturbation below which the steady states are always stable, and

this threshold depends on the full nonlinear form of f (N).ForN

1

, for example, the

necessary threshold perturbation is N

2

− N

1

.

dN

dt

= f (N)

N

1

N

2

N

3

N

Stable

Stable

Unstable

0

Figure 1.3. Population dynamics model dN/dt = f (n) with several steady states. The gradient f

(N ) at the

steady state, that is, where f (N) = 0, determines the linear stability.

1.2 Insect Outbreak Model: Spruce Budworm 7

1.2 Insect Outbreak Model: Spruce Budworm

A practical model which exhibits two positive linearly stable steady state populations is

that for the spruce budworm which can, with ferocious efficiency, defoliate the balsam

fir; it is a major problem in Canada. Ludwig et al. (1978) considered the budworm

population dynamics to be modelled by the equation

dN

dt

= r

B

N

1 −

N

K

B

− p(N).

Here r

B

is the linear birth rate of the budworm and K

B

is the carrying capacity which

is related to the density of foliage (food) available on the trees. The p(N)-term repre-

sents predation, generally by birds: its qualitative form is important and is illustrated

in Figure 1.4. Predation usually saturates for large enough N. There is an approximate

threshold value N

c

, below which the predation is small, while above it the predation

is close to its saturation value: such a functional form is like a switch with N

c

being

the critical switch value. For small population densities N, the birds tend to seek food

elsewhere and so the predation term p(N) drops more rapidly, as N → 0, than a linear

rate proportional to N. To be specific we take the form for p(N) suggested by Ludwig

et al. (1978), namely, BN

2

/(A

2

+ N

2

) where A and B are positive constants, and the

dynamics of N(t) is then governed by

dN

dt

= r

B

N

1 −

N

K

B

−

BN

2

A

2

+ N

2

. (1.6)

This equation has four parameters, r

B

, K

B

, B and A, with A and K

B

having the same

dimensions as N, r

B

has dimension (time)

−1

and B has the dimensions of N(time)

−1

.

A is a measure of the threshold where the predation is ‘switched on,’ that is, N

c

in

Figure 1.4. If A is small the ‘threshold’ is small, but the effect is just as dramatic.

Before analysing the model it is essential, or rather obligatory, to express it in

nondimensional terms. This has several advantages. For example, the units used in the

analysis are then unimportant and the adjectives small and large have a definite relative

meaning. It also always reduces the number of relevant parameters to dimensionless

groupings which determine the dynamics. A pedagogical article with several practical

examples by Segel (1972) discusses the necessity and advantages for nondimensionali-

p(N)

0

NN

c

Figure 1.4. Typical functional form of the

predation in the spruce budworm model; note the

sigmoid character. The population value N

c

is an

approximate threshold value. For N < N

c

predation

is small, while for N > N

c

, it is ‘switched on.’

8 1. Continuous Population Models for Single Species

sation and scaling in general. Here we introduce nondimensional quantities by writing

u =

N

A

, r =

Ar

B

B

, q =

K

B

A

,τ=

Bt

A

(1.7)

which on substituting into (1.6) becomes

du

dτ

= ru

1 −

u

q

−

u

2

1 +u

2

= f (u;r, q), (1.8)

where f is defined by this equation. Note that it has only two parameters r and q,which

are pure numbers, as also are u and τ of course. Now, for example, if u 1 it means

simply that N A. In real terms it means that predation is negligible in this population

range. In any model there are usually several different nondimensionalisations possible

and this model is no different. For example, we could write u = N/K

B

,τ = t/r

B

and

so on to get a different form to (1.8) for the dimensionless equation. The dimensionless

groupings to choose depend on the aspects you want to investigate. The reasons for the

particular form (1.7) become clear below.

The steady states are solutions of

f (u;r, q) = 0 ⇒ ru

1 −

u

q

−

u

2

1 +u

2

= 0. (1.9)

Clearly u = 0 is one solution with other solutions, if they exist, satisfying

r

1 −

u

q

=

u

1 +u

2

. (1.10)

Although we know the analytical solutions of a cubic (Appendix B), they are often

clumsy to use because of their algebraic complexity; this is one of these cases. It is

convenient here to determine the existence of solutions of (1.10) graphically as shown

in Figure 1.5(a). We have plotted the straight line, the left of (1.10), and the function

on the right of (1.10); the intersections give the solutions. The actual expressions are

not important here. What is important, however, is the existence of one, three, or again,

one solution as r increases for a fixed q, as in Figure 1.5(a), or as also happens for a

fixed r and a varying q.Whenr is in the appropriate range, which depends on q,there

are three equilibria with a typical corresponding f (u;r, q) as shown in Figure 1.5(b).

The nondimensional groupings which leave the two parameters appearing only in the

straight line part of Figure 1.5 are particularly helpful and was the motivation for the

nondimensionalisation introduced in (1.7). By inspection u = 0, u = u

2

are linearly

unstable, since ∂ f/∂u > 0atu = 0, u

2

, while u

1

and u

3

are stable steady states, since

at these ∂ f/∂u < 0. There is a domain in the r, q parameter space where three roots

of (1.10) exist. This is shown in Figure 1.6; the analytical derivation of the boundary

curves is left as an exercise (Exercise 1).

This model exhibits a hysteresis effect. Suppose we have a fixed q,say,andr

increases from zero along the path ABCD in Figure 1.6. Then, referring also to Fig-

ure 1.5(a), we see that if u

1

= 0atr = 0theu

1

-equilibrium simply increases monoton-

(b)

(a)

r

u

1

u

2

u

3

q

u

g(u)

h(u)

f (u)

0

u

1

u

2

u

3

u

Figure 1.5. Equilibrium states for the spruce budworm population model (1.8). The positive equilibria are

given by the intersections of the straight line r(1 −u/q) and u/(1 +u

2

). With the middle straight line in (a)

there are 3 steady states with f (u;r, q) typically as in (b).

r

1 Steady state

1 Steady state

3 Steady states

1/2

0

A

B

C

D

q

P

Figure 1.6. Parameter domain for the number of positive steady states for the budworm model (1.8). The

boundary curves are given parametrically (see Exercise 1) by r(a) = 2a

3

/(a

2

+ 1)

2

, q(a) = 2a

3

/(a

2

− 1)

for a ≥

√

3, the value giving the cusp point P.

10 1. Continuous Population Models for Single Species

ically with r until C in Figure 1.6 is reached. For a larger r this steady state disappears

and the equilibrium value jumps to u

3

. If we now reduce r again the equilibrium state

is the u

3

one and it remains so until r reaches the lower critical value, where there is

again only one steady state, at which point there is a jump from the u

3

to the u

1

state. In

other words as r increases along ABCD there is a discontinuous jump up at C while as

r decreases from D to A there is a discontinuous jump down at B.Thisisanexample

of a cusp catastrophe which is illustrated schematically in Figure 1.7 where the letters

A, B, C and D correspond to those in Figure 1.6. Note that Figure 1.6 is the projection

of the surface onto the r, q plane with the shaded region corresponding to the fold.

The parameters from field observation are such that there are three possible steady

states for the population. The smaller steady state u

1

is the refuge equilibrium while u

3

is the outbreak equilibrium. From a pest control point of view, what should be done to

try to keep the population at a refuge state rather than allow it to reach an outbreak sit-

uation? Here we must relate the real parameters to the dimensionless ones, using (1.7).

For example, if the foliage were sprayed to discourage the budworm this would reduce

q since K

B

, the carrying capacity in the absence of predators, would be reduced. If

the reduction were large enough this could force the dynamics to have only one equi-

librium: that is, the effective r and q do not lie in the shaded domain of Figure 1.6.

Alternatively we could try to reduce the reproduction rate r

B

or increase the threshold

number of predators, since both reduce r which would be effective if it is below the crit-

ical value for u

3

to exist. Although these give preliminary qualitative ideas for control,

it is not easy to determine the optimal strategy, particularly since spatial effects such as

C

B

C

steady state

u

q

A

B

D

r

Figure 1.7. Cusp catastrophe for the equilibrium states in the (u

steadystate

, r, q) parameter space. As r in-

creases from A, the path is ABCCD while as r decreases from D, the path is DC BBA. The projection of

this surface onto the r, q plane is given in Figure 1.5. Three equilibria exist where the fold is.

1.2 Insect Outbreak Model: Spruce Budworm 11

budworm dispersal must be taken into effect; we shall discuss this aspect in detail in

Chapter 2, Volume II.

It is appropriate here to mention briefly the timescale with which this model is con-

cerned. An outbreak of budworm during which balsam fir trees are denuded of foliage

is about four years. The trees then die and birch trees take over. Eventually, in the com-

petition for nutrient, the fir trees will drive out the birch trees again. The timescale for

fir reforestation is of the order of 50 to 100 years. A full model would incorporate the

tree dynamics as well; see Ludwig et al. (1978). So, the model we have analysed here

is only for the short timescale, namely, that related to a budworm outbreak.

Hassell et al. (1999) have considered the original highly complex (more than 80

variables and parameters) multi-species interaction model involving large and small

larvae, fecundity, foliage mortality with and without the budworm, and other players

in the interaction. They show, using gross, but reasonably justifiable assumptions, that

the model can be simplified without losing the basic budworm–forest interaction. They

obtain several simplifications using asymptotic limits, eventually reducing the system

to three difference (as opposed to differential) equations for larvae, foliage and area

fraction of old trees. Analysis showed that the mechanism for oscillations could be

captured with only two equations. A more in depth analysis than we have done here, but

very much less than that by Hassell et al. (1999), is given in the very practical book on

modelling by Fowler (1997).

Catastrophes in Perception

Although the following does not strictly belong in a chapter on population dynamics, it

seemed appropriate to include it in the section where we discuss hysteresis and catas-

trophic change.

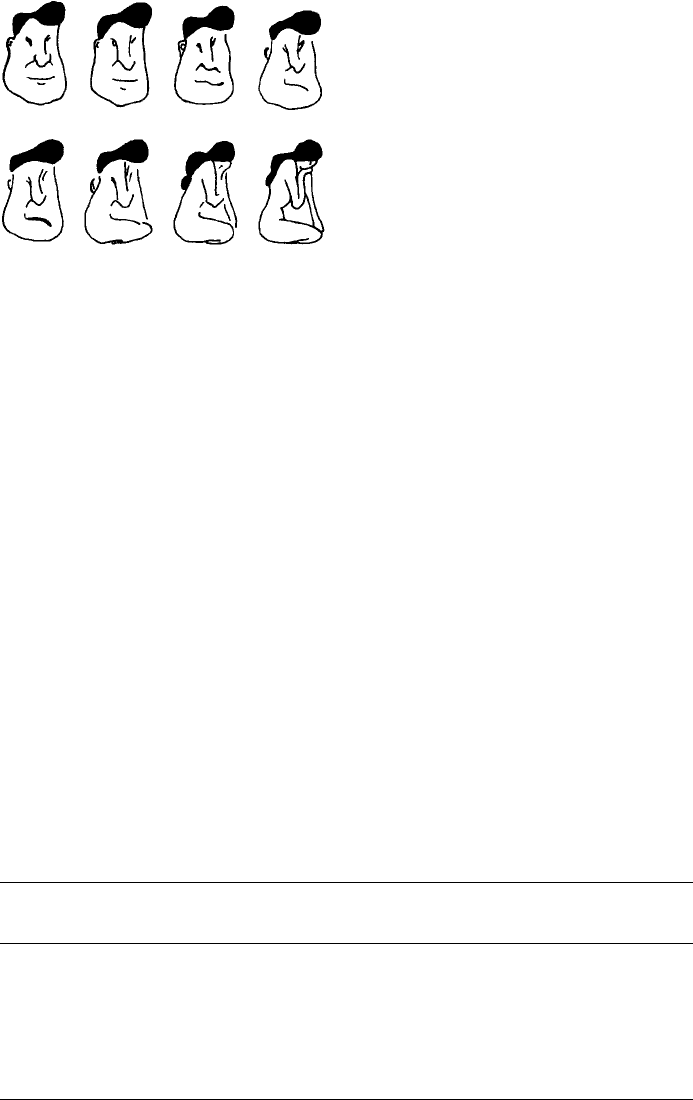

There is a series of now classic figures developed by Fisher (1967) which demon-

strate sudden changes in visual perception. Here we describe one of these picture series

and show that it is another example of a cusp catastrophe; it also exhibits an initial per-

ceptual hysteresis. We also present the results of an experiment carried out by the author

which confirms the hypothesis. The specific example we describe has been studied in

more depth by Zeeman (1982) and more generally by Stewart and Peregoy (1983).

The mind can be triggered, or moved in a major new thought or behavioural direc-

tion, by a vast variety of cues in ways we cannot yet hope to describe in any biologi-

cal detail. A step in this direction, however, is to be able to describe the phenomenon

and demonstrate its existence via example. Such sudden changes in perception and be-

haviour are quite common in psychology and therapy.

4

The series of pictures, numbered 1 to 8 are shown in Figure 1.8.

4

An interesting example of a major change in a patient undergoing psychoanalysis treated by the French

psychoanalyst Marie Claire Boons is described by Zeeman (1982). The case involved a frigid woman whom

she had been treating for two years without much success. ‘One day the patient reported dreaming of a frozen

rabbit in her arms, which woke and said hello. The patient’s words were “un lapin congel

´

e,” meaning a frozen

rabbit, to which the psychoanalyst slowly replied “la pin con gel

´

e?” This is a somewhat elaborate pun. The

word “pin” is the French slang for penis, the female “la” makes it into the clitoris, “con” is the French slang

for the female genitals, and “gel

´

e” means both frozen and rigid. The surprising result was that the patient did

not respond for 20 minutes and the next day came back cured. Apparently that evening she had experienced

her first orgasm ever with her husband.’

12 1. Continuous Population Models for Single Species

Figure 1.8. Series of pictures exhibiting abrupt

(catastrophic) visual change during the variation

from a man’s face to a sitting woman. (After

Fisher 1967)

The picture numbered 1 in the figure is clearly a man’s face while picture 8 is

clearly a sitting woman. An experiment which demonstrates the sudden jump from see-

ing the face of a man to the picture of the woman is described by Zeeman (1982). The

author carried out a similar experiment with a group of 57 students, none of whom had

seen the series before nor knew of such an example of sudden change in visual per-

ception. The experiment consisted of showing the series three times starting with the

man’s face, picture 1, going up to the woman, picture 8, then reversing the sequence

down to 1 and again in ascending order; that is, the figures were shown in the order

1234567876543212345678. The students were told to write down the numbers where

they noticed a major change in their perception; the results are presented in Table 1.2.

The predictions were that during the first run through the series, that is, from 1 to 8,

the perception of most of the audience would be locked into the figure of the face until

it became obvious that the picture was in fact a woman at which stage there would be

sudden jump in perception. As the pictures were shown in the reverse order the audience

was now aware of the two possibilities and so could make a more balanced judgement

as to what a specific picture represented. The perception change would therefore more

likely occur nearer the middle, around 5 and 4. During the final run through the series

the change would again occur near the middle.

The results of Table 1.2 are shown schematically in Figure 1.9 where the vertical

axis is perception, p, and the horizontal axis, the stimulus, the picture number. The

Table 1.2. Numbers for the perceptual catastrophe experiment involving 57 undergraduates, none of whom

had seen the series nor had heard of the phenomenon before.

Sequence Sequence

Direction Picture Sequence Mean Direction

→ 12345678

number switching 00005825197.0

12345678 ←

number switching 0 111729 6 3— 4.8

→ 12345678

number switching —03191912 3 1 4.9

1.3 Delay Models 13

woman

perception

man

switch 3

switch 2

switch 1

DW

M

stimulus

biifurcation

point

Maxwell

point

biifurcation

point

1234 5678

A

D

C

Figure 1.9. Schematic representation of the visual catastrophe based on the data in Table 1.2 on three runs

(1234567876543212345678) through the series of pictures in Figure 1.8. The stimulus switches occurred at

points denoted by 1, 2 and 3 in that order.

graph of perception versus stimulus is multi-valued in a traditional cusp catastrophe

way. Here, over part of the range there are two possible perceptions, a face or a woman.

The relation with the example of the budworm population problem is clear. On the first

run through the switch was delayed until around picture 7 while on the run through

the down sequence it occurred mainly at 5 and again around 5 on the final run through

the pictures. There is, however, a fundamental difference between the phenomenon here

and the budworm. In the latter there is a definite and reproducible hysteresis while in the

former this hysteresis effect occurs only once after which the dynamics is single valued

for each stimulus.

If we had started with picture 8 and again run the series three times the results would

be similar except that the jump would have occurred first around 2, as in the figure, with

the second and third switch again around 5. The phenomenon of catastrophic change in

behavior and perception is widespread and an understanding of the underlying dynamics

would clearly be of great help. Several other qualitative examples in psychology are

described by Zeeman (1977).

1.3 Delay Models

One of the deficiencies of single population models like (1.4) is that the birth rate is

considered to act instantaneously whereas there may be a time delay to take account

of the time to reach maturity, the finite gestation period and so on. We can incorporate

such delays by considering delay differential equation models of the form

dN(t)

dt

= f

(

N(t), N(t − T )

)

, (1.11)

14 1. Continuous Population Models for Single Species

where T > 0, the delay, is a parameter. One such model, which has been used, is an

extension of the logistic growth model (1.2), namely, the differential delay equation

dN

dt

= rN(t)

1 −

N(t − T )

K

, (1.12)

where r, K and T are positive constants. This says that the regulatory effect depends

on the population at an earlier time, t − T , rather than that at t. This equation is itself

a model for a delay effect which should really be an average over past populations and

which results in an integrodifferential equation. Thus a more accurate model than (1.12)

is, for example, the convolution type

dN

dt

= rN(t)

1 −

1

K

t

−∞

w(t −s)N(s) ds

, (1.13)

where w(t) is a weighting factor which says how much emphasis should be given to

the size of the population at earlier times to determine the present effect on resource

availability. Practically w(t) will tend to zero for large negative and positive t and will

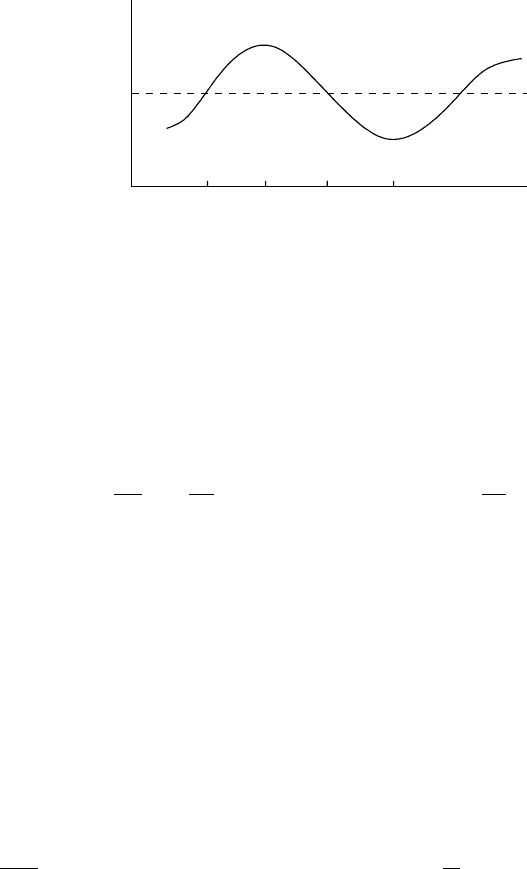

probably have a maximum at some representative time T. Typically w(t) is as illustrated

in Figure 1.10. If w(t) is sharper, in the sense that the region around T is narrower

or larger, then in the limit we can think of w(t) as approximating the Dirac function

δ(t − T ),where

∞

−∞

δ(t − T ) f (t) dt = f (T ).

Equation (1.13) in this case then reduces to (1.12)

t

−∞

δ(t − T −s)N(s) ds = N(t − T ).

The character of the solutions of (1.12), and the type of boundary conditions re-

quired are quite different from those of (1.2). Even with the seemingly innocuous equa-

tion (1.12) the solutions in general have to be found numerically. Note that to compute

the solution for t > 0 we require N(t) for all −T ≤ t ≤ 0 . We can however get

some qualitative impression of the kind of solutions of (1.12) which are possible, by the

following heuristic reasoning.

w(t)

0

T

t

Figure 1.10. Typical weighting function w(t) for

an integrated delay effect on growth limitation for

the delay model represented by (1.13).

1.3 Delay Models 15

N(t)

K

t

1

t

1

+T

t

2

t

1

+T

t

Figure 1.11. Schematic periodic solution of the delay equation population model (1.12).

Refer now to Figure 1.11 and suppose that for some t = t

1

, N(t

1

) = K and that

for some time t < t

1

, N(t − T )<K . Then from the governing equation (1.12), since

1 − N(t − T )/K > 0, dN(t)/dt > 0andsoN(t) at t

1

is still increasing. When

t = t

1

+ T , N(t − T ) = N (t

1

) = K and so dN/dt = 0. For t

1

+ T < t < t

2

,

N(t − T)>K and so dN/dt < 0andN(t) decreases until t = t

2

+ T since then

dN/dt = 0 again because N(t

2

+ T − T ) = N(t

2

) = K. There is therefore the

possibility of oscillatory behaviour. For example, with the simple linear delay equation

dN

dt

=−

π

2T

N(t − T ) ⇒ N(t) = A cos

πt

2T

,

where A is a constant. This solution, which can be easily verified, is periodic in time.

In fact the solutions of (1.12) can exhibit stable limit cycle periodic solutions for a

large range of values of the product rT of the birth rate r and the delay T .Ift

p

is the

period then N(t+t

p

) = N(t) for all t. The point about stable limit cycle solutions is that

if a perturbation is imposed the solution returns to the original periodic solution as t →

∞, although possibly with a phase shift. The periodic behaviour is also independent of

any initial data.

From Figure 1.11 and the heuristic argument above, the period of the limit cycle

periodic solutions might be expected to be of the order of 4T . From numerical calcu-

lations this is the case for a large range of rT, which, incidentally, is a dimensionless

grouping. The reason we take this grouping is because (1.12) in dimensionless form

becomes

dN

∗

dt

∗

= N

∗

(t

∗

)

1 − N

∗

t

∗

− T

∗

, where N

∗

=

N

K

, t

∗

= rt, T

∗

= rT.

What does vary with rT, however, is the amplitude of the oscillation. For example,

for rT = 1.6, the period t

p

≈ 4.03T and N

max

/N

min

≈ 2.56; rT = 2.1, t

p

≈

4.54, N

max

/N

min

≈ 42.3; rT = 2.5, t

p

≈ 5.36T, N

max

/N

min

≈ 2930. For large values

of rT, however, the period changes considerably.

This simple delay model has been used for several different practical situations.

For example, it has been applied by May (1975) to Nicholson’s (1957) careful experi-

mental data for the Australian sheep-blowfly (Lucila cuprina), a pest of considerable

importance in Australian sheep farming. Over a period of nearly two years Nicholson