Mullins L.J. Management and organisational behaviour, Seventh edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

design between the social elements (such as people’s psychological and social needs)

and technical elements (such as the apparatus and its physical location) of the organi-

sational ‘system’. Trist

12

has been an influential writer in this area, and, as Buchanan

and Huczynski have observed, he and his co-researchers argued that:

an effective socio-technical system design could never fully satisfy the needs of either sub-system

... This ‘sub-optimisation’ is a necessary feature of good socio-technical design. There are trade-

offs which must be accepted. Clearly a system designed with an emphasis on social needs and

ignoring technical system needs could quickly run into technical problems. Conversely, a system

designed according only to the demands of technology could be expected to generate social and

organisational difficulties. What is required is a design approach aimed at ‘joint optimisation’ of

the social and technical components and their requirements.

13

What is more, ‘The final design is a matter of organisational choice, not technological

imperative,’

14

whereas for the technological determinists the technology itself has by

far and away the most influence.

Much writing and analysis about technical change within this tradition has been

strongly influenced by the labour process perspective, put back on the Sociology of

Organisations and Work agenda by Braverman. It is argued that the social and econ-

omic ‘outcomes’ of technical change must be understood through the location of

events and decisions within the wider dynamics of capitalism, accumulation and the

imperative of profitability for organisational survival. This is achieved through the

intensification of management control over labour through the deskilling and degrada-

tion of work.

15

Thus, technology is one of the means used by managers to retain and

extend control and deskill work (the use of IT for the monitoring and surveillance of

work and employees being but one example). Scientific management (discussed in

Chapter 3) was seen by Braverman as the main means used by management to deskill

work and extend their control over other employees.

The key point about the Radical/Marxist perspective here is that it is not the tech-

nology per se which deskills jobs (as would be the burden of the technological

determinist’s view), but rather the latter is:

entirely a product of the need to control the labour process in order to increase profits. Under a dif-

ferent social system, advanced technology would open up the possibility of different forms of job

design and work organization which would benefit the workforce. This would involve workgroups

possessing the engineering knowledge required to operate and maintain the technology, and a

rotation of tasks to make sure everyone had opportunities to work on both highlycomplex and rou-

tine jobs. In other words, rather than being deskilled, they would retain autonomy and control over

the labour process, and advanced technology would be used as a complement to, rather than a

substitute for, human skills and abilities ... such a form of work organization and control could not

be brought about without a major political, economic and social transformation.

16

The preoccupation with the labour surveillance and control issue can also be seen in

that research and writing on technological/organisational change which has deployed

the metaphor of the ‘electronic panopticon’ to draw attention to the insidious and not-

so-insidious ways in which IT has been used by managers to monitor and record the

work of employees, in some cases in such a way that they do not know exactly when

they are being watched, but are aware that this could be at any time, and hence act as

if they are under surveillance all the time.

17

There are some significant connections

here with social power issues. A particularly influential writer here has been Zuboff.

18

She distinguishes between the ‘automating’ (the replacement of actions of the human

body by the machine) and ‘informating’ potential of IT (the simultaneous generation of

new information about organisational activities). It is the latter, according to Zuboff,

which presents a ‘transformative’ possibility to organisations through the transparency

CHAPTER 17 TECHNOLOGY AND ORGANISATIONS

665

Radical/Marxist

perspectives

which it offers. The problem is that this potential is rarely realised, because the neces-

sary associated organisational changes do not occur (devolution of responsibility and

influence etc.), as pre-existing modes of organisation structuring and working practices

continue, allied now to the use of IT as an electronic panopticon.

The focus of this perspective is much more strongly upon:

the assumption that the outcomes of technological change, rather than being determined by the

logic of capitalist development, or external technical and product market imperatives, are in fact

socially chosen and negotiated within organisations by organisational actors.

19

An influential early study was conducted by Pettigrew, who examined organisational

politics and decision-making associated with the development and structuring of com-

puter applications. He showed, for example, how the head of a management services

department was able to influence decisions in the computerisation domain through

taking up a ‘gatekeeper’ role which allowed him to ‘shape’ the information reaching

the key managerial decision-makers.

20

Wilkinson studied the political behaviour associated with organisational and human

resource issues arising out of technical change on the shopfloor, including particularly

the skill and control dimensions, and again demonstrated that a range of choices had

been made and were available with respect to work organisation, control and

skill/deskilling of jobs.

21

His work is particularly important for drawing attention to the

fact that:

the outcomes of technological change within particular organisations are dependent not only on

the mediation of lower levels of managers, but also on the way workers respond, adapt and try to

influence the outcome ... [thus] social choice and negotiation over technological change must be

seen in the context of organisational arrangements and working practices that have already been

decided upon and contested, and are thereby part of the custom and practice of the workplace.

22

The influential technological change research of Buchanan and Boddy was also located

within the political/processual perspective. They argued, for example, that ‘the capabil-

ities of technology are enabling, rather than determining’, and that it is ‘decisions or

choices concerning how the technology will be used’ and not the technology itself,

which leads to the organisational outcomes.

23

A more recent example of authors adopting a political/processual perspective associated

with the use of technology (in this case information and communication technology)

comes from Hayes and Walsham’s research into working practices and discourse around the

deployment of Lotus Notes in a case study of a company selling medical products.

24

Lotus

Notes were introduced in order to facilitate the collaborative working of employees across

and within functional specialisms. Some shared databases proved to have more heightened

political content than others, and this affected the quality of the interaction between

employees and between employees and managers. To illustrate, the sharing of information

and ideas was not as extensive in some cases as in others – Hayes and Walsham attribute

this to such political factors as ‘young careerists’ trying to draw attention to themselves

(showing how hard-working they are, for example) through the data they put up, and ‘old-

stagers’/non-careerists not being concerned with such matters, and hence not going to

such trouble. What was communicated via the technology also appeared to be a function

of who was known/suspected to be looking – for example, the statement of a senior man-

ager that he was going to read and contribute to a particular site impacted upon what was

subsequently placed on that site.

It is also worth noting in drawing this section to a close that Preece’s research on organi-

sations and technological change in the 1990s was strongly influenced by a political/

processual perspective.

25

This work will be discussed in some detail later in the chapter.

666

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Political/

processual

approaches

Here, the focus is upon the ways in which the technology is shaped by (rather than

itself shaping, as with the technological determinist perspective) the economic, techni-

cal, political, gender and social circumstances in which it is designed, developed and

utilised.

26

These factors are embodied in the emergent technology, and therefore tech-

nology alone does not have an ‘impact’. SST often draws upon Marxian and gender

analyses, and argues that:

capitalism and patriarchy are primary contexts that influence the development and use of tech-

nologies. That is, the emergence of new technologies in some way responds to the expression of

class and gender interests – whether through the industrial military, the domination of scientific

and technological spheres of activity by men or through the activities of particular organisations

in the economy.

27

It is important to note, however, as McLoughlin and Harris have argued, that from the

SST perspective:

Technology is accorded a specific causal status: the idea that technology has ‘causal effects’ on

society is rejected, but the idea of technological influences on the shaping of technology itself is

not. A precondition of much technological innovation is in fact seen to be existing technology.

28

Rather than seeing technology emerging from a rational-linear process of invention,

design, development and innovation, SCT draws upon the sociology of scientific

knowledge to examine the unfolding of technological change over time in its social

and economic contexts to show that technology is created through a multi-

actor/multi-directional process.

29

It is argued that there is a range of technological

options available or identifiable, which a variety of people, groups and organisations

(such as suppliers, designers, IT specialists, engineers) seek to promote or challenge.

These people’s concerns are partly technical, but also social, moral, and economic.

These ‘relevant’ social groups define the ‘problem’ for which the artefact is intended to

be a ‘solution’. Technical change occurs where either sufficient consensus emerges for a

particular design option or a design option is imposed by a powerful actor or group;

search activity and debate is then closed, and the technology is ‘stabilised’ in a particu-

lar configuration. From this point on, it is possible to talk about ‘impacts’ or ‘effects’

on the organisation in general, working practices, skill requirements, etc., but, as with

SST, these effects are not purely technical. It is important to note, however, that while:

The social constructivist argument does not deny that material artefacts have constraining influ-

ences upon actors … it does hold a question-mark over what these constraints are. Such

constraints – or enablers – do not acquire their significance without interpretative action on the

part of humans, hence there can be no self-evident ortransparent account of such ‘material con-

straints’. There are, of course, more persuasive accounts and less persuasive accounts – but they

remain accounts, not reflections.

30

An influential variant within the SCT perspective, associated particularly with the

research of Bijker,

31

is that relating to so-called ‘socio-technical ensembles’ (it should be

noted that this work has little, if any, connection with the socio-technical systems

approaches discussed earlier). Here, technology is seen as a key constituent element of

the ensemble, which emerges within the social, economic and political contexts of the

organisation. Bijker stresses the organisational politics dimension of the creation and

maintenance of the ensemble:

Such an analysis stresses the malleability of technology and the possibility for choice, the basic

insight that things could have been otherwise. But technology is not always malleable, it can

also be obdurate, hard and very fixed. The second step is to analyse this obduracy of socio-

technical ensembles, to see what limits it sets to our politics.

32

If an organisation is seen as a collection of groups, each of which has a particular tech-

nological ‘frame’, then political behaviour is seen as centring around attempts to

CHAPTER 17 TECHNOLOGY AND ORGANISATIONS

667

The socio-

economic

shaping of

technology

(SST)

The social

construction of

technology

(SCT)

achieve ascendancy for a particular frame, and often it is those groups which already

have more power that are the most successful in this process. The socio-technical

ensemble, then, embodies a web of relationships between individuals, groups, technol-

ogy and internal and external organisational contexts. It is dynamic, and the exercise

of power plays a key role in shaping and moulding it. The ‘Butler Co.’ case study,

which follows later in the chapter, illustrates how this particular perspective on tech-

nology and organisations can be used to analyse organisational behaviour, and

provides more detail about the perspective itself.

Actor–Network Analysis (ANA) is associated particularly with the work of Callon, Latour and

Law.

33

It is argued that actors define one another and their relationships through inter-

mediaries such as literary inscriptions (e.g. books and magazines), technical artefacts (e.g.

computers and machines), skills (e.g. the knowledge possessed by people), and money.

They attempt to construct networks which will bring together a range of these human

and non-human actants. The key to understanding ANA is its argument that:

‘the relationship between the technological and the social cannot be understood by reductionist

arguments which view either the technological or the social as ultimately determining. Whether it

is the technological, social factors or other material or natural factors which determine the rela-

tionship between the technical is a complex empirical question the answer to which will vary from

context to context. No definitive line can therefore be drawn between that which is ‘technological’

and that which is ‘social’.

34

A, if not the, key concern of ANA, then, is to try to establish, in specific work and

organisational contexts, ‘the processes whereby relatively stable networks of aligned

interests are created and maintained, or alternatively to examine why such networks

fail to establish themselves’.

35

From the ANA perspective, then, technology has a robustness or facticity, and thus

makes a difference in and of itself to organisational processes and ‘outcomes’. As

Coombs et al.

36

have noted:

‘Callon’s treatment of non-humans ... in a similar way to humans ... is not intended to be anthro-

pomorphic – the fact that they intervene in processes does not mean they have motives and

intentions of their own. It is intended to underline ... the fact that technology is not infinitely plas-

tic, to be shaped in any way whatsoever by social forces, any more than technology is driven

solely by its own internal logic, independentlyof society.’

At the same time, however, ANA theorists are very reluctant to attach any major role or

influence in their explanations and theories to pre-existing macro social structures,

such as social classes and markets. They have been criticised for ‘ceding too much

power and autonomy to individual actors and eschewing existing social theory, leaving

them poorly equipped to explain particular developments and beset by a tendency to

offer mainly descriptions and post-hoc explanations’.

37

Like SCT, TTM draws on the sociology of scientific knowledge; however, TTM does not

accept the proposition that technology becomes ‘stabilised’ – that is, that it comes to

have some identifiable ‘objective’ implications, characteristics and capabilities.

38

Considerations such as what technologies are, what they can and cannot do, and what

effects they have, are seen as always a socially negotiated phenomenon; technologies are

only understood or ‘read’ in the particular social contexts in which they are found. Actor-

networks of humans and non-humans create and sustain specific conceptualisations of

what is ‘social’ and what is ‘technical’, and the relationship between them.

It follows, according to this perspective, that different representations of the nature

of technologies/organisations can be created using different metaphors or ‘readings’,

and thus the focus of interest turns to, not what a particular technology can or cannot

668

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Actor–Network

Analysis

Technology as

text and

metaphor

(TTM)

do, but rather how such accounts (of what it can do) are derived.

39

McLoughlin and

Harris have referred to TTM as an ‘extreme’ relativist position, arguing that its key

problem is that:

the influence of broader social structure and distributions of power, even organisational struc-

ture and the roles of competing stakeholder interests are viewed as superfluous to the analysis of

technology and technological change. It is as if the ‘lid’ of the ‘technological black box’ has been

‘opened’ but then shut firmly tight behind the analyst.

40

Two final comments are in order in drawing this section to a close:

1 The chosen categorisation of perspectives on technology is inevitably somewhat

arbitrary, and it would not be difficult to think of other ways in which this complex

and heterogeneous field of study could be divided (there are also some omissions,

due to constraints of space, one being ‘gender and technology’).

2 The concern has been merely to define and briefly describe each perspective; space

does not permit the inclusion of extended critiques of each perspective, of which

there are a large number.

41

Let us now illustrate how a socio-technical ensemble perspective can be used to aid the

understanding of organisational structuring and practices which incorporate a strategic

deployment of technology. To do this, we will draw upon a case study by Blosch and

Preece of a consumer goods company where the focus was upon the configuration of

the work and technology of sales representatives.

42

The exercise of managerial power

played a key part in shaping organisational action. This truncated version of the origi-

nal paper, in the main, only extracts, outlines and analyses those features relating more

immediately to technology deployment, and thus in order to gain a much fuller pic-

ture and understanding of the other influential managerial, social and organisational

aspects it is necessary to consult the original.

‘Butler Co’. is a UK-based company which sells its products into a mature and highly

competitive market. The company changed ownership twice during the 1990s, and was

‘de-layered’ and rationalised, leading to a very flat organisation structure where the

number of line managers between a sales representative and the CEO is only three. The

reps work from home, thus they do not require any costly office space; their interac-

tion with the organisation is strongly mediated by information technology. The sales

team was charged with two key objectives: to increase market share and to gather mar-

keting information. As a senior manager put it:

It has been a strategy of the company to work in the most efficient way possible, and a necessity

of the market. We cannot afford a complex and rigid administrative structure which limits our

flexibility, that’s why the company is driven from the top. All the troops have to worry about is

doing their job, we pay them well enough for it. I know that may sound draconian, but in such a

competitive market we cannot afford the luxury of pluralism, decisions must be made and acted

on as quickly as possible. Information technology plays a central role in that, in fact without it it

would not be possible for us to be such an aggressive market-led company.

Senior management continually reiterated three themes: the marketplace is highly compet-

itive and volatile; the only way to manage this is through centralised decision–making; and

central to the latter is the deployment of information technology. The pivotal role played

by IT is illustrated by the following observation of a Board member:

We meet once a month, in our game you have to; a brand that you have invested millions in can

go down the tubes in a matter of weeks, so you need to be in a position to change tack very rap-

idly. These days you also have to watch out for legislation and public opinion, the tide is against

CHAPTER 17 TECHNOLOGY AND ORGANISATIONS

669

USING A SOCIO-TECHNICAL ENSEMBLE PERSPECTIVE: THE CASE

OF BUTLER CO.

us now so we have to be very careful. Not proliferating these issues across the company means

that decisions are taken quickly. The technology allows us to get all the information needed and

fast, we don’t have to wait around for it, at the worst it’s only a day old, it allows us to control

every aspect of our business very quickly. I suppose you could summarise our approach as

‘market led, rapid response using information technology’.

Let’s make no bones about it, the technology is the eyes and ears of the organisation. I suppose

the best analogy is that of a brain, the brain is the Board and the technology is the nerves, gath-

ering information and passing it to the brain. Impulses from the brain can also travel very quickly

to where something needs to be done. Despite the fact we are a trading company, we are kept

profitable and in business by the technology. (CEO)

Butler Co.’s IT-based management information system was described as ‘state of the art’

by a number of managers and other staff. It is highly confidential, with only the most

senior managers being allowed access to the data and analyses which are produced:

We paid a lot of money for the MIS to be written, and it does some very hard sums! The market

analysis section is particularly complicated and uses all the goodies-factor analysis, cluster

analysis, data mining, you name it. The best part is that this is all brought together into a simple-

to-use clicky-button frontend. They [the senior management team] sit there in their meetings

huddled over the group decision support system; it’s rather like a cross between NASA and a

witches’ huddle. (Technical Director)

Because of the wide geographical spread and diversity of the organisation, senior man-

agement contend that it is only possible for information – and indeed the organisation

itself – to be controlled, through IT, by a small central group of senior staff:

As an organisation we are structured around the insight that information is our key resource. That

information flows to the centre and forms the basis of our management decisions. We draw this

information from right across the organisation, and bring it together into an integrated whole. The

senior management team then interpret this and the decisions made are fed back out through the

system to the individual units [via area managers]; this can be from a whole division right down to

an individual employee. I don’t see any way that a modern organisation can be responsive and pro-

vide a significant return on investment without taking this approach. (Marketing Director)

The management style of Butler Co. is Tayloristic and autocratic:

We employ them to do what they are told, I don’t see anything wrong with that. We make it per-

fectly clear before they join that that’s the way it is, they are paid to do their job and do it well,

and that’s it. Quite frankly, we pay them well above the odds, and we never have any shortage of

applicants. (Human Resources Director)

During a training session for new sales reps, the Divisional Director used the analogy of

the reps being the ‘worker bees’ of the organisation. The implication was that they

were paid to work and not to think, the latter being the province of senior manage-

ment. As a sales rep commented:

We are just the hired hands, we are paid well to do our job well, and that’s it. They [senior manage-

ment] don’t want us to take part in the running of the company in any way. I suppose that’s the deal:

‘We pay you well to do your job and to keep your nose out of our business.’ As long as you can detach

your self-esteem from your job, then it’s bearable, otherwise you can end up feeling demoralised.

The remuneration package that Butler Co. offered its sales reps was relatively generous,

and, as a rep observed, ‘It’s the “golden handcuffs” – you rapidly become used to the

money, and can’t leave, and they know it, so they’ve got you by the balls.’ The remu-

neration package helps secure employee compliance:

Of course that’s the case, it suits the organisation. We are here to maximise the profits to our

shareholders, nothing else. The shareholders benefit greatly from our approach, but so do the

employees. Their emotional and spiritual welfare is not our problem. Naturally, we hope they

670

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

Using

information

technology

The Golden

Handcuffs

enjoy their jobs, our approach is ‘Do your job well and we’ll give you generous pay, pensions,

bonuses and holidays’. Simple, that keeps most of our reps very happy. (HR Director)

The marketing database and associated systems are linked to the reps via a specially

designed computer terminal, which resembles a small laptop. The terminal has a data

communication port and external modem, and at the end of each day the data

recorded is downloaded to the company’s marketing database. The program requires

the rep to enter a range of details relating to the calls (such as the brands sold, com-

petitor brand details) by cycling through a number of defined screens, each of which

must be completed before the next may be accessed. When all the screens have been

completed, the call may be closed.

For the great majority of sales reps their working day starts at 8 am, with the first job

being to turn on the terminal and log in, which takes the rep to the outlet screen. The

reps are required to operate on a cycle basis agreed with their Area Manager, the calls

for the current working day being displayed on the terminal screen. They use the ter-

minal constantly, and thus their work is continually mediated by it. They do not see it

as detached from the rest of their work, but rather ‘part and parcel’ of it: ‘In the old

days you would fill in a form with a biro, now you use the terminal – it’s the same

thing. The terminal is harmless in itself, the problem is that management just don’t

trust us’ (Sales rep). The terminal program guides the reps through each screen, and

calls cannot be closed until all the screens have been completed:

The terminal makes sure that you do all that the company wants for each call, you can’t close a

call until all the data is entered. But that’s not enough, the terminal tells you what to do, but in a

broad way. The points system is like a fine control, the company tells us exactly what should be

done to the finest detail. The terminal gathers all the information to make sure you have done it,

and you know that you will be measured against the points system and rewarded or punished

depending on how you did. It’s rather clever really, on the face of it you work from home, but in

reality it’s just like having your manager standing right beside you every second of the day from

the time you log on to the time you download your data. (Sales rep)

This cycle is repeated throughout the working day. Once the allotted calls have been

completed, the reps return home, where they complete a number of ‘house-keeping’

procedures. Finally, the terminal is connected to the modem and recharger to down-

load data and recharge the batteries for the next day. The whole process takes between

one and two hours.

Once a week the sales reps receive a print-out of their performance during the previous

week from their Area Manager. The analysis compares each rep against the others in the

region on key factors such as days worked, sales calls, ‘out of stocks’ encountered, ‘out of

stocks’ rectified, new introductions (new brands taken on by the retailer). Often the Area

Manager will include his/her observations on the performance. A rep observed:

It makes me laugh, 1984 isn’t a work of fiction – it’s our management handbook. Big Brother

watches us all the time, we have only one objective, determined by the party, and any contradic-

tory thoughts we may have we must submerge with doublethink. But the sweetest paradox of this

is our desperate compliance, we engage in this insanity because our very lifestyle depends on it,

we cannot believe this is the best way to work, and yetwe must preserve this way of working

because we do so well out of it. We are trapped by our own greed!

Senior management played the key and determining role in designing, implementing

and monitoring the socio-technical ensemble which both enabled and constrained

the work and working practices of the sales reps. It was within this ensemble that the

nature and quality of the relationships between the actors, and between the actors and

the technology, were set out: senior management made the decisions, the reps carried

out their instructions, and middle management (that is, the Area Managers) ensured

that the reps complied.

CHAPTER 17 TECHNOLOGY AND ORGANISATIONS

671

Sales reps:

working

practices

Commentary

Let us now assume that particular configurations of technology (hardware and soft-

ware) are available from technology suppliers and also that, in some organisations at

least, there exists the capability to change, develop and amend the technology (for

example, in an Information Systems or Engineering department). The focus will be

upon social, political, managerial and organisational issues, opportunities and chal-

lenges associated with getting the technology into the organisation in the first place,

and then its subsequent introduction, implementation and everyday utilisation.

Drawing in the main upon SST, SCT and political/processual perspectives, let us pose

the question ‘How does technology come to be used in organisations in particular

ways, given that it has been influenced by the particular objectives and strategies

developed and employed by certain people, and the socio-economic contexts in which

they are located?’ A key to understanding this is to study what happens before the new

technology comes to have a physical presence within the organisation.

This adoption phase, as Preece has termed it,

43

presents a range of choices for the

actors involved with respect to a number of matters relating to new technology utilisa-

tion, which occurs after implementation. The concerns and objectives of those people

who are not involved might be taken into account by those who are, but that is

another matter, and is certainly at best an indirect form of involvement.

What is being referred to here by the phrases ‘technology’ and ‘technological

change’? The reference is to microelectronics and microprocessors, telecommunica-

tions and Internet technologies (ICTs), as applied in manufacturing processes,

information sharing and processing, service provision, and products themselves. These

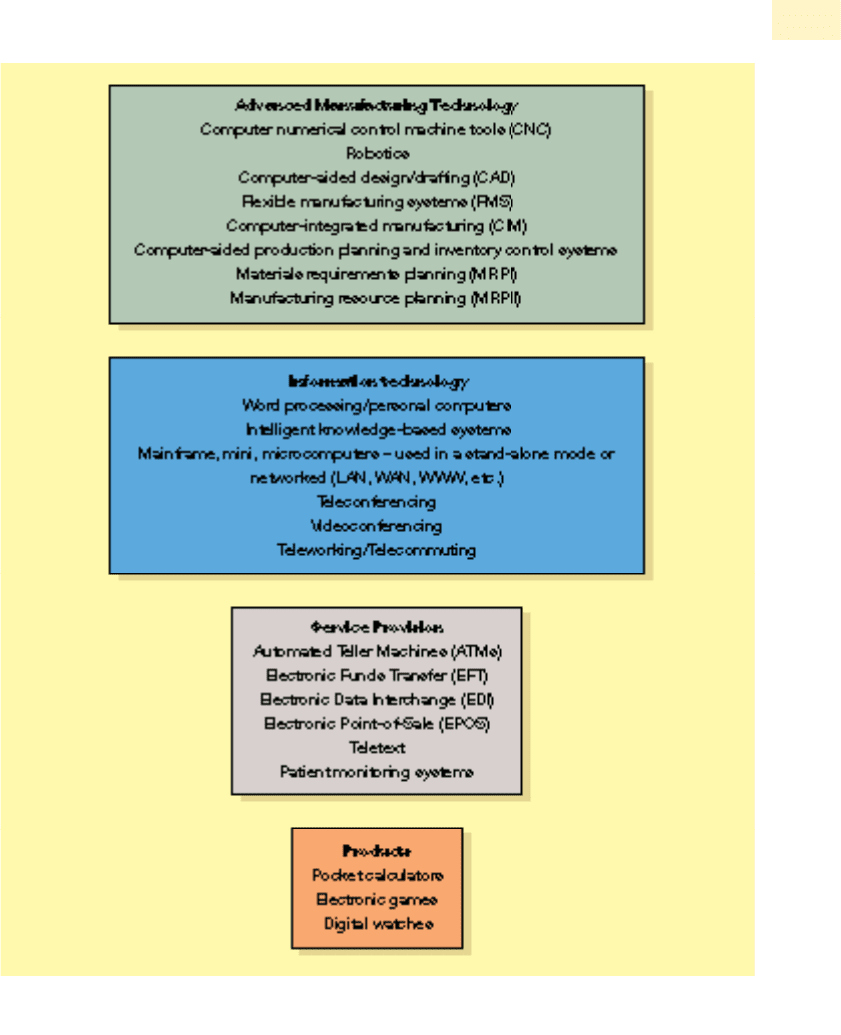

main forms or applications may be summarised as follows:

■ Manufacturing/engineering/design technology – sometimes referred to as ‘Advanced

Manufacturing Technology’ (AMT) or ‘Computer-Aided Engineering’ (CAE).

■ Technology used for information capture, storage, transmission, analysis and

retrieval. It may be linked to AMT/CAE or may be used separately in information-

sharing and dissemination in administrative and managerial functions across a

variety of organisations and in teleworking and telecommuting.

■ Technology employed in the provision of services to customers, clients, patients, etc.

in service sector applications.

■ Technology as the product itself.

Figure 17.1 provides some examples

of the different forms these tech-

nologies can take.

There is in practice often overlap

between the forms and applications

of new technology, and Figure 17.1

is by no means an exhaustive list.

It is worth noting that some of this

technology has been in existence and

available to organisations for varying

periods of time (the extent to which it

has been taken up by organisations,

or ‘diffused’, is, however, another

matter). Numerical control and com-

puter numerical control machine

tools, for example, have been in exis-

tence since the 1940s and 1950s. New

developments and applications in

hardware and software are coming

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE AND ORGANISATIONS

Grid supercomputers, forming a technological ‘PC farm’

672

Photo: David Parker/Science Photo Library

onto the market all the time, and the take-up rate of the varieties of new technology is also

continually expanding as more and more people in organisations become aware of its

potential (and as its cost reduces in real terms).

In 1989 Friedman and Cornford

44

argued that computer systems had undergone three

main phases of development:

■ their beginnings are to be found in universities and defence industries in the 1940s,

dominated by hardware problems, and lasting until the mid-1960s;

■ the second phase lasted from the mid-1960s until the early 1980s, and was domi-

nated by software development; and

■ the third phase centred upon user relations.

CHAPTER 17 TECHNOLOGY AND ORGANISATIONS

673

Figure 17.1 Examples of technologies and technology applications

(Adapted from Preece, D. A. Organisations and Technical Change: Strategy, Objectives and Involvement, Routledge/ITBP (1995), p. 3)

They predicted a fourth phase, which would be focused upon exploiting the strategic

potential of new technology, and would be realised through the installation of com-

puter networks linking people and organisations over time and space. With the benefit

of hindsight, we can note that this was an accurate prediction! Subsequent to the pub-

lication of their book, there has been much talk about and evidence of the emergence

of the variously labelled ‘network’, ‘distributed’, ‘knowledge-based’, ‘virtual’, etc. etc.

organisation, facilitated by, if not dependent upon, electronic and telecommunication

means of data gathering, analysis, dissemination and communication.

45

Information and communication technology (ICT) is inherently flexible, and there-

fore allows a good deal of choice with regard to how and for which purposes it is

utilised in the organisation in terms of such matters as working practices, skill and con-

trol, and job design. This flexibility is the result of four key features:

1 its compactness (compare an old, non-new technology mainframe computer of

1960s’ vintage, which took up space equivalent to a lecture theatre, and yet had a

processing power considerably less than that of a modern desk-top microcomputer);

2 low energy-use and hence low running costs;

3 decreasing cost in relation to (increasing) processing power;

4 software which, of course, can be edited and reprogrammed, thus providing flexibil-

ity of application.

In recent years a number of organisations have adopted an open systems architecture

and moved away from being locked into particular computer suppliers/manufacturers,

thus flexibility is also achieved by using telecommunications to link different makes and

models of computers together, both within and across the same and different organisa-

tions and workplaces (including homes – see, for example, the Butler Co. case study).

The upshot of the above characteristics of technology is that the ways in which it is

utilised, and therefore the implications for such matters as the nature of managerial

and employee work around the technology, have much to do with social and eco-

nomic processes (for example, decision-making) within and without workplaces and

organisations. In other words, social choice is significant. Thus, it is important to know

who is making the choices and who gets involved in the ‘design space’ which is

opened up by technology.

By ‘new’ here we do not mean ‘new’ in a temporal sense. The technology may have

been available for some years, but it is only now that a given organisation has decided

to introduce it – hence the reference is to the fact that it is new to a particular organisa-

tion at a particular point in time. However, it is, of course, possible that the technology

is new in both senses, that is, it has only just become available from a supplier and a

given organisation has more or less immediately adopted it – an ‘early adopter’, to use

a common phrase here.

Preece

46

has developed a framework which identifies two phases and seven stages of

new technology adoption and introduction (see Figure 17.2).

The adoption phase consists of four stages: initiation, progression/feasibility, invest-

ment decision, and planning and systems design. It is only after this phase has been

completed, in however cursory a manner, that it is possible to talk about the new tech-

nology coming to have a physical presence in the organisation – that is, it is at the first

stage of being introduced into the organisation, which is the beginning of the second

phase, consisting of Stages 5 to 7.

It is important to emphasise that it is not implied that the adoption process is inher-

ently rational and systematic, in the sense, for example, that all organisations have to

674

PART 6 ORGANISATIONAL STRUCTURES

ADOPTING AND INTRODUCING NEW TECHNOLOGY